Abstract

Study Objectives:

This study assessed generalists' perceptions and challenges in providing care to sleep disorders patients and the role of sleep specialists in improving gaps in care.

Methods:

A mixed-method approach included qualitative (semi-structured interviews, discussion groups) and quantitative (online surveys) data collection techniques regarding care of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and shift work disorder (SWD).

Results:

Participants: OSA: generalists n = 165, specialists (internists, neurologists, psychiatrists, pulmonologists) n = 12; SWD: generalists n = 216, specialists n = 108. Generalists reported challenges in assessing sleep disorders and diagnosing patients with sleep complaints. Generalists lacked confidence (selected ≤ 3 on a 5-pt Likert scale) in managing polypharmacy and drug interactions (OSA: 54.2%; SWD: 62.6%), addiction (OSA: 61.8%), and continuous positive airway pressure (OSA: 66.5%). Generalists in both studies reported deficits in knowledge of monitoring sleep disorders (OSA: 57.7%; SWD: 78.7%), rather relying on patients' subjective reports; 23% of SWD generalists did not identify SWD as a medical condition. Challenges to generalist-specialist collaboration were reported, with 66% of generalists and 68% of specialists in the SWD study reporting lack of coordination as a barrier. Generalists reported lack of consistency in sleep medicine and a perceived lack of value in consulting with sleep specialists.

Conclusions:

Knowledge and attitudinal challenges were found in primary care of patients with sleep disorders. Sleep specialists need to clarify and educate practitioners regarding primary care's approach.

Citation:

Hayes SM; Murray S; Castriotta RJ; Landrigan CP; Malhotra A. (Mis) perceptions and interactions of sleep specialists and generalists: obstacles to referrals to sleep specialists and the multidisciplinary team management of sleep disorders. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8(6):633-642.

Keywords: Sleep disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, shift work disorder, primary care, qualitative research, physician competence, multidisciplinary care

Inadequate sleep is widespread in the United States,1,2 affecting approximately 50–70 million Americans.1 Chronic lack of sleep and insomnia have important physiological and health effects as well as psychological, cognitive, safety, social, and economic implications.3 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and shift work disorder (SWD) are two common sleep disorders with potentially serious social impact. OSA affects roughly 5% to 10% of the U.S. population or 18 million Americans,4 including an estimated 11.6% of the shift work population.5 Shift work disorder, interruption of the normal sleep/wake cycle by the need to work shifts, or non-traditional daytime hours, and is referred to as circadian rhythm sleep disorder, shift work type, or shift work disorder (SWD).6 Approximately 20% of workers are estimated to work non-traditional schedules.7 Of these, 10% have been found to experience SWD.8

In spite of their prevalence, substantial impact, and the availability of effective treatment strategies, sleep disorders are generally underdiagnosed and undertreated by healthcare providers.1,2 The annual Sleep in America survey2 reported that 86% of respondents' generalists had never discussed sleep with them. Six of ten healthcare professionals reported not having enough time to discuss sleep problems during office visits.2 Even when patients were asked about sleep issues, providers neither managed them directly nor referred patients to specialists. In another study, 90% of generalists rated their knowledge of sleep disorders as fair or poor.9 Patients of sleep specialists exhibited greater awareness of the OSA management process, though no difference was seen in their acceptance or compliance with CPAP.10 This pattern of diagnostic delay and misdiagnosis has been seen with narcolepsy as well.11

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Sleep disorders are generally under-diagnosed and undertreated by primary care providers and not optimally referred to sleep specialists. However, there has been limited in depth assessment of the etiology of barriers faced by generalists in their assessment of sleep disorders, and how to optimize the role of sleep specialists in patient care.

Study Impact: Knowledge, skill, and attitudinal challenges and gaps were identified among a national sample of primary care providers involved in the care of patients with sleep disorders, resulting in patients being under-diagnosed, undertreated, stigmatized, and under-prioritized. Challenges in understanding and enhancing the role and value of the sleep specialist to the primary care community, as well as incorporating them to the interdisciplinary team for optimal care, were also identified. This study reveals a deficit in generalist physician knowledge about sleep medicine and a large gap between generalist and specialist attitudes concerning the diagnosis and management of sleep disorders.

Collaboration between generalists and sleep specialists has been recommended to alleviate the gaps in primary care providers' knowledge of sleep disorders,12 with guidelines for OSA recommending multidisciplinary team care.13 However, true multidisciplinary, shared care—while logical—can be challenging to achieve. Specialists reported that while some primary care physicians have been receptive to sleep education in the past, they were reluctant to take the responsibility for interpreting polysomnography results and for treatment.9 Further, the healthcare system as a whole has not adapted to the care of sleep disorders patients and does not provide the resources or infrastructure needed to provide effective care across the continuum of the patient experience for sleep disorders.9

In light of these and related data, the Institute of Medicine called for efforts to expand the awareness of sleep disorders among healthcare professionals through education and training.1 However, barriers to primary providers' diagnosis and management of sleep disorders remain largely unknown. Moreover, we wished to gain a better understanding of the issues and challenges between generalists and sleep specialists that might undermine optimal patient care. Consequently, we conducted a national applied behavioral performance needs assessment with the following goals:

To identify challenges, as well as educational and performance gaps of generalist primary care physicians in providing care to sleep disorders patients, focusing on OSA and SWD.

To assess the roles, perceptions, attitudes, and interactions of generalists and sleep specialists in providing care for patients with sleep disorders.

To provide a baseline to evaluate the impact and outcomes of future educational and performance improvement interventions.

METHODS

Following IRB approval, we conducted educational and performance needs assessments among nationwide samples of participants that focused on challenges and gaps in the treatment and management of OSA (data collection May – August 2008) and SWD (data collection March – June 2009). Mixed-methods approach that included both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques in a triangulated research design were employed.14,15 A triangulated research design involves examination of several data sources using multiple data collection methods to examine the same phenomena,15,16 enhancing the trustworthiness and validity of the findings.

Participants

Purposive sampling was used to ensure that the sample was representative of the target audience.15,16 Participants were drawn from existing subject pools and recruited via telephone, fax, and e-mail in collaboration with the American Thoracic Society (ATS, www.thoracic.org), the New Jersey Academy of Family Physicians (NJAFP, www.njafp.org), the Office of Continuing Medical Education of the University of Virginia School of Medicine (UVA-OCME, www.medicine.virginia.edu/education/more/cme/home-page), and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Office of Continuing Professional Development (UW-SMPH-OCPD, www.ocpd.wisc.edu). The nature of the distribution of the invitations precluded identifying and following up with non-responders. Institutional review board approval was obtained for both studies. Financial compensation was provided to participants for their time.

Generalist participants were family physicians and internists who reported seeing at least one patient with sleep disorders (OSA or SWD) per month or whose patient population included ≥ 2% of patients who worked > 8 h/day and/or outside traditional daytime hours (07:00–18:00).17 Specialists (internists specializing in sleep, neurologists, psychiatrists, pulmonologists) were included who saw ≥ 1 patient/month with sleep disorders (OSA or SWD) or who reported having ≥ 5% of their patients who worked shifts. The inclusion criteria were determined in collaboration with faculty and a review of the literature.

Data Collection

Best practices and challenges in the care of patients with OSA and SWD were identified through a comprehensive literature review. Key concepts provided a framework to guide the design of qualitative data collection instruments. Topics to emerge from this process included contextual issues, gaps throughout the continuum of care, inter-professional collaboration and referral gaps, and specific educational needs in sleep disorders. Based on this framework, comprehensive discussion group and semi-structured interview guides were developed to explore the practice and experiences of generalists and specialists. The discussion groups were lead by an expert-facilitator who asked participants questions related to the developed framework. Participants were encouraged by the facilitator to share their thoughts and opinions, and engage with their peers on the topics discussed. For in-depth understanding, probes consisting of open-ended questions addressing issues around knowledge, skill, attitudes, healthcare team and system, and current and desired practice were used in the discussion groups and interviews. Discussion groups were approximately 3.5 h and interviews were approximately 60 minutes. Both discussion groups and interviews were audio-recorded.

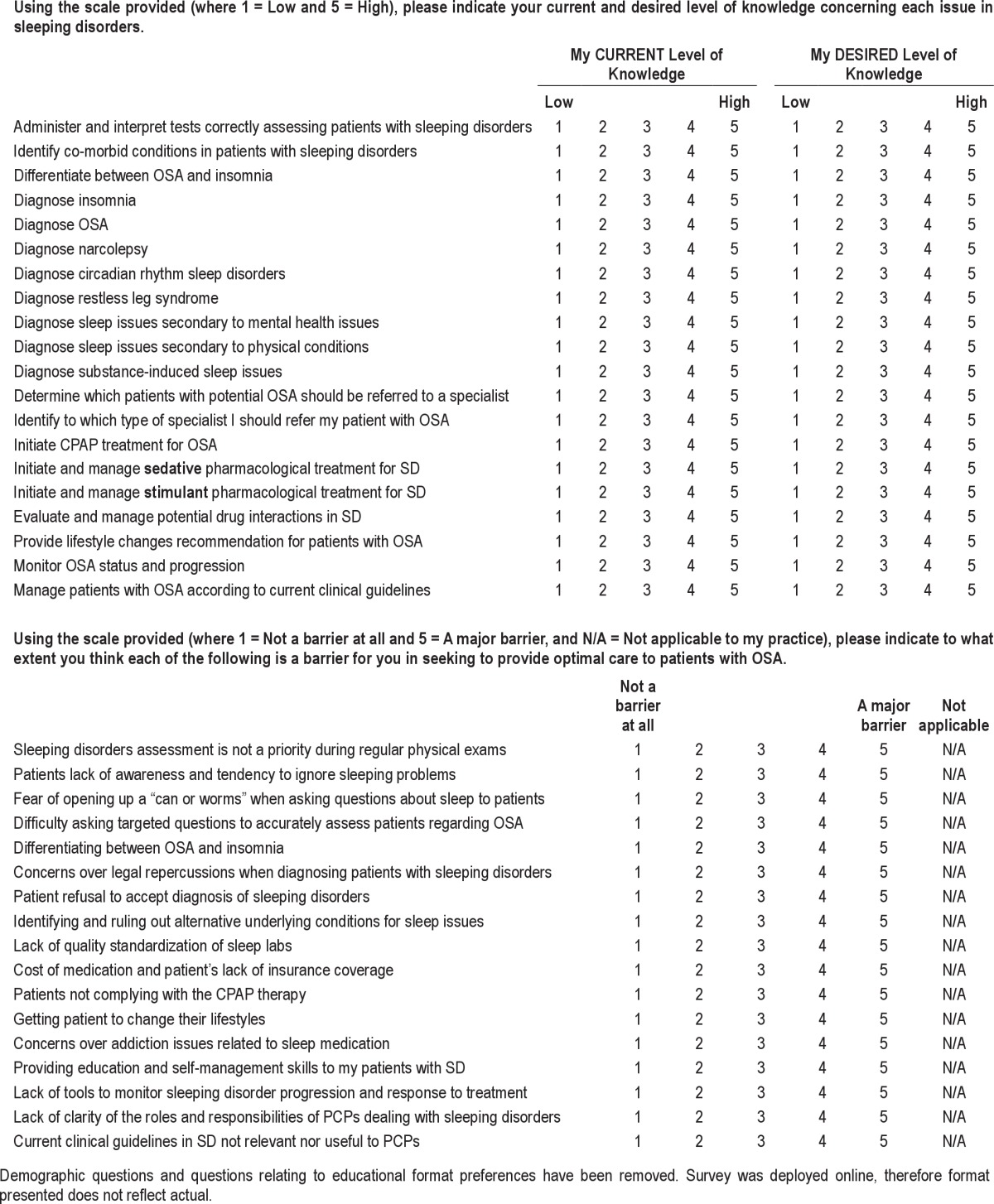

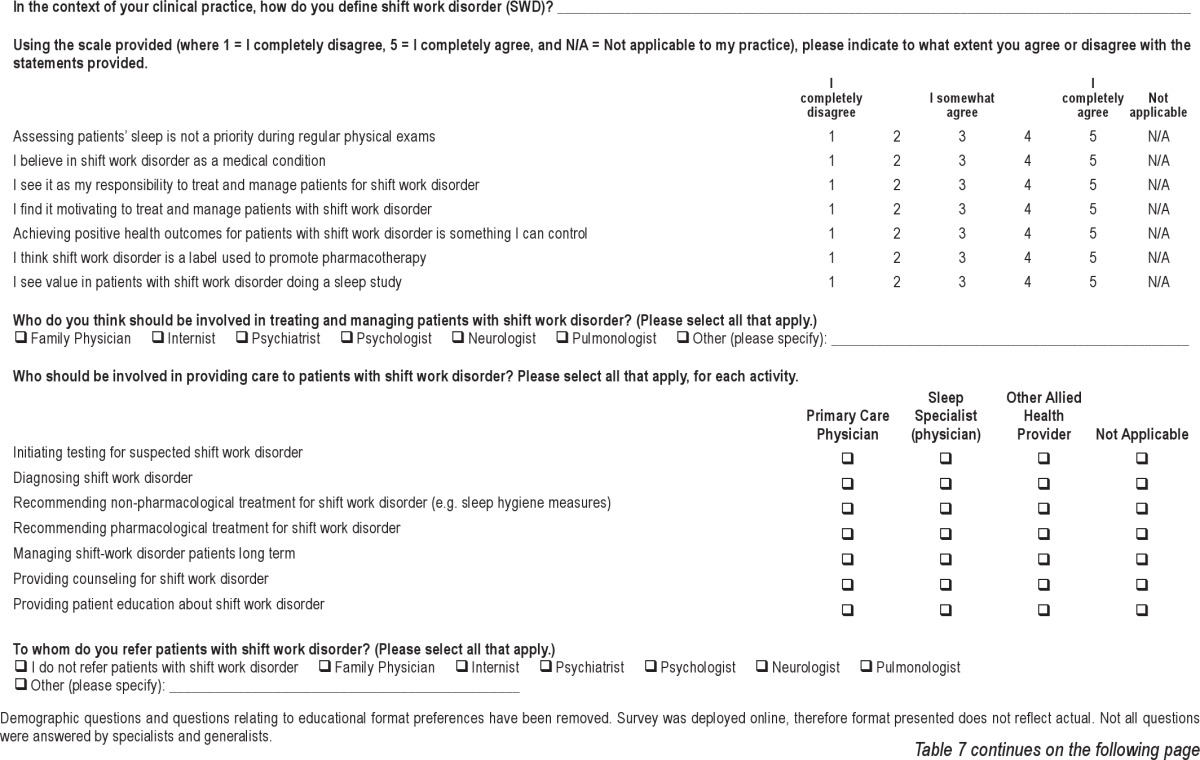

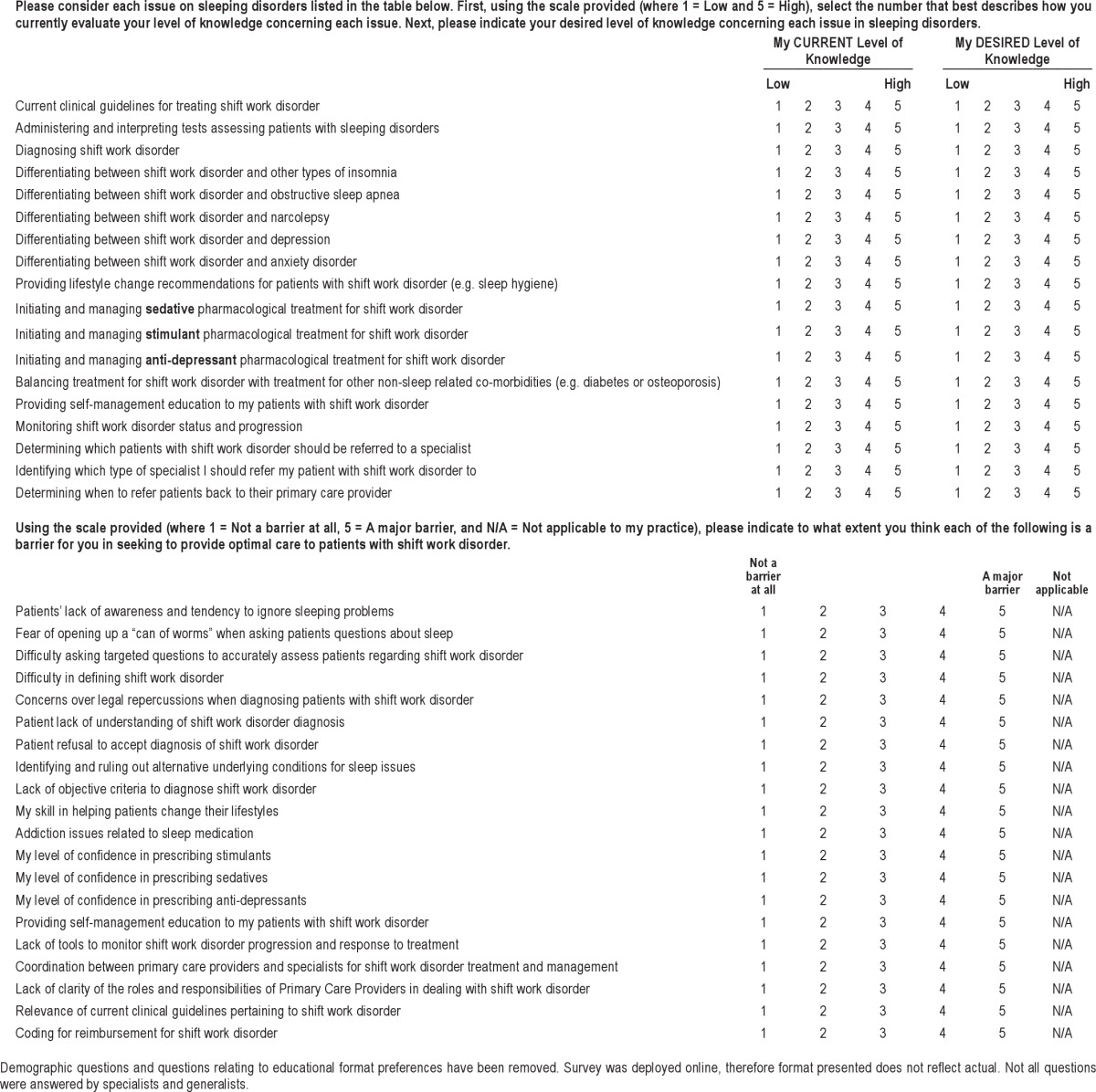

Quantitative surveys were developed based on substantive qualitative findings and key concepts identified in the literature review. The OSA survey consisted of 48 items, and the SWD survey of 75–78 items, consisting of rating statements on a 5-point scale (where 1 = low, 5 = high; see Tables 6 and 7). For example, participants were asked to select the number that best describes how they currently evaluate their knowledge relative to the statement presented. Next, they were asked to indicate their desired level of knowledge, defined as the level the participants would like to have or feel they need to attain.

Table 6.

Excerpt of questionnaire on obstructive sleep apnea completed by generalists

Table 7.

Excerpt of questionnaire on obstructive sleep apnea completed by generalists and specialists

Analysis

Qualitative analysis was through open coding.18 Coders were experienced qualitative researchers, including co-authors SH, SM, and KC. Coding categories were then grouped into related themes and subthemes, such as: Knowledge—lack of knowledge of diagnostic testing, and Attitude—lack of prioritization of sleep disorders. Themes were validated among coders through review of selected data excerpts and discussion of coding. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until concordance was achieved. Concordance was achieved in all cases. Selective coding was then conducted,18 whereby data were systematically coded with respect to core concepts identified in the literature review and analysis of interview data.

Quantitative analysis consisted of descriptives (means, frequencies), (SPSS 12.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Gap analysis was carried out, in which participants provided a self-assessment of both their current level and desired level of knowledge.14 The difference, or gap, between current and desired levels provides an indicator of specific areas of educational need. ANOVA validated the statistical significance of these gaps. A 5-point Likert agreement scale was used throughout each of the two surveys.

RESULTS

Findings revealed contextual and attitudinal barriers as well as clinical challenges across the continuum of care of patients with sleep disorders, regardless of specific diagnosis, and indicated key challenges relevant to inter-professional collaboration between generalists and sleep specialists.

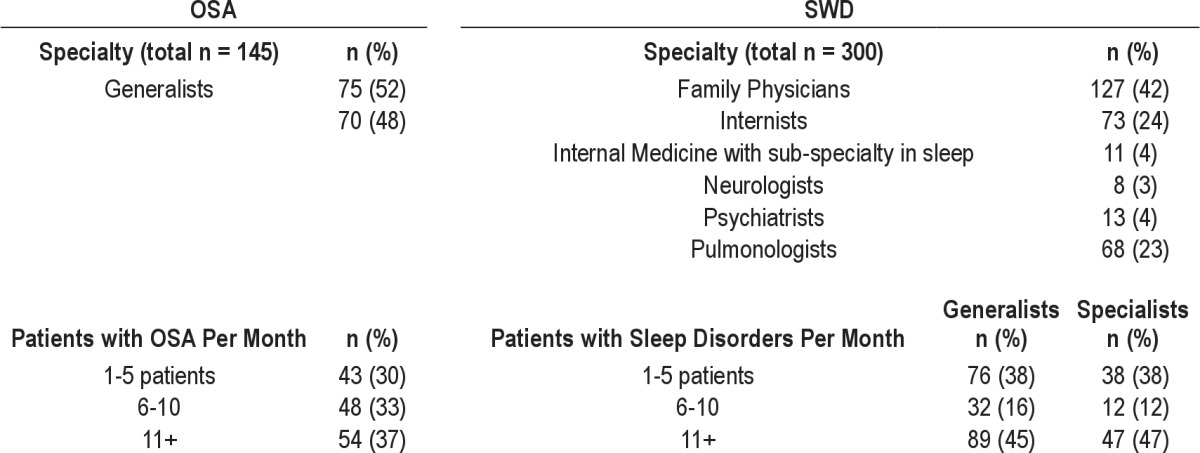

Sample (Table 1 and 2)

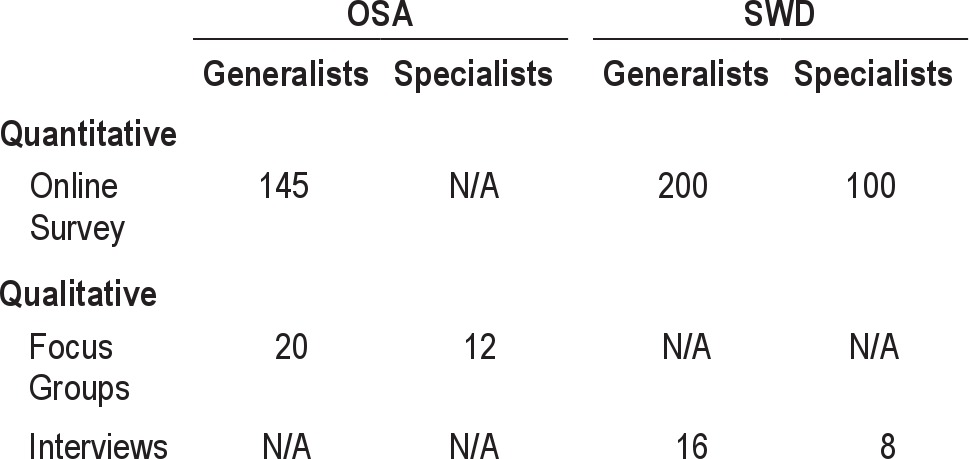

Table 1.

Sample distribution by data collection activity

Table 2.

Sample distribution of physicians participating in the online surveys

Five discussion groups (n = 32), 24 interviews, and 445 surveys were completed for a total sample of 401 participants. Forty physicians (7.7%) participated in both OSA and SWD studies. Seventy-three percent of physicians participating in the OSA study saw > 10 patients/month, compared to 45% of physicians in the SWD study.

Knowledge and Skill in Care of Patient with Sleep Disorders

Screening and Diagnosis

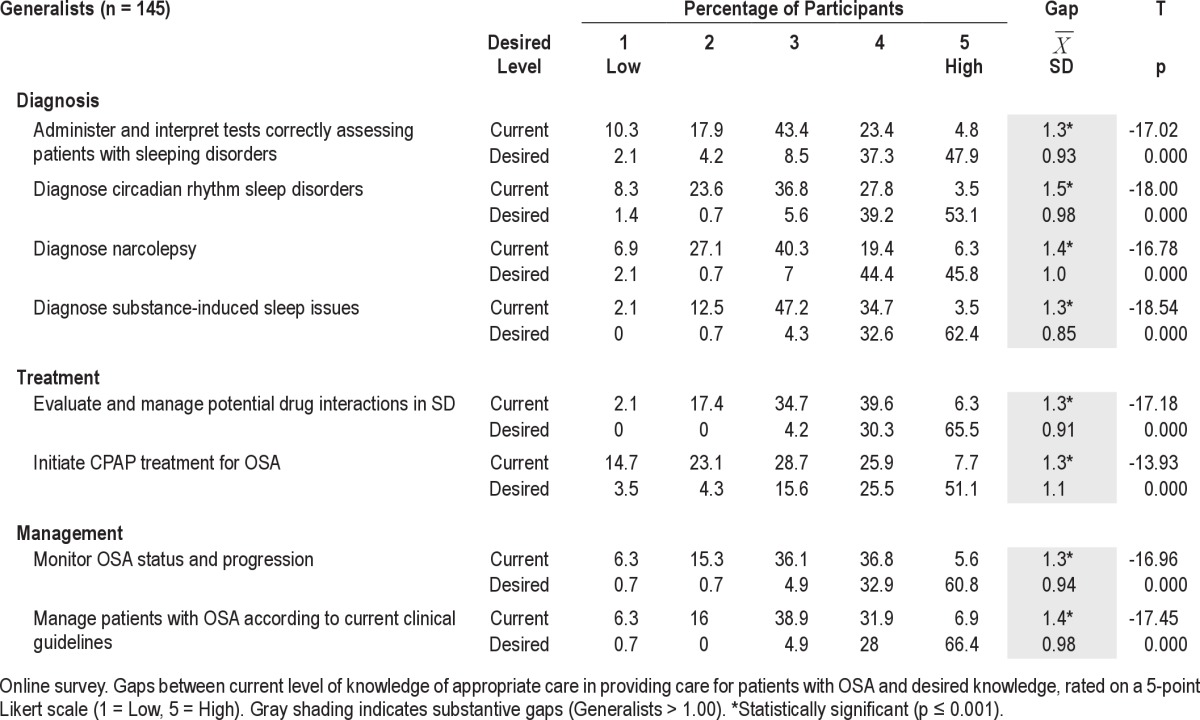

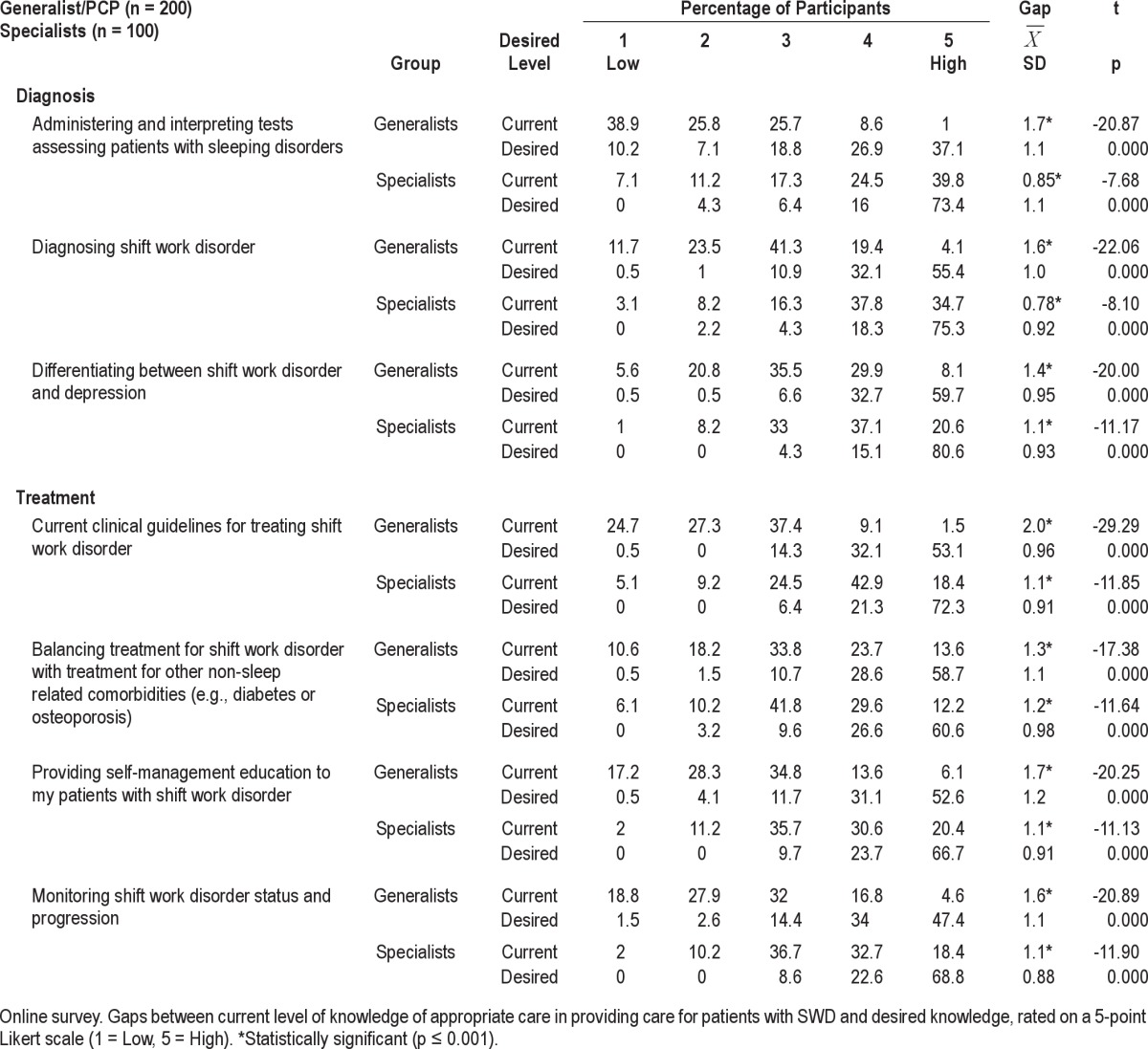

One-third of generalists in the SWD and OSA studies expressed hesitancy in addressing both OSA and SWD, neither systematically nor proactively screening for sleep disorders, and were reluctant to raise the topic because they perceived sleep disorders as a complex issue to manage. Participants in the OSA study identified substantive knowledge gaps on assessment and differential diagnosis across multiple sleep disorders (Table 3). Physicians in the SWD study identified an even greater lack of knowledge of diagnosis of SWD (Table 4), lacking knowledge of key questions to pose to make an accurate diagnosis and relying on subjective impressions and patient reports to support their diagnosis, rather than formal tools, guidelines, or criteria.

Table 3.

Gaps analysis in care of patients with OSA

Table 4.

Gap analysis in care of patients with SWD

Treatment and Management

Challenges were also identified in the treatment of sleep disorders. Generalists in both studies articulated a lack of confidence in dealing with polypharmacy and evaluation of drug interactions, describing reluctance to prescribe stimulants for daytime due to fear of addiction, and lack of knowledge of treatment cessation. Generalists in the OSA study described knowledge gaps with regard to initiating CPAP therapy (Table 3) as well as supporting patients on CPAP. Generalists in both studies reported relying on patients' subjective reports in monitoring patients and treatment outcomes. Generalists did not characterize guidelines as useful in determining their care

Attitudes toward Sleep Disorders

Generalist participants generally did not prioritize discussing sleep disorders. They further demonstrated a lack of understanding of the impact of sleep disorders on patients' daily living and comorbid conditions. While the majority of physicians believed in SWD as a medical condition, 23% of generalists and 16% of specialists did not. Some generalists in the OSA study reported characterizing sleep disorders as a symptom rather than as a primary diagnosis.

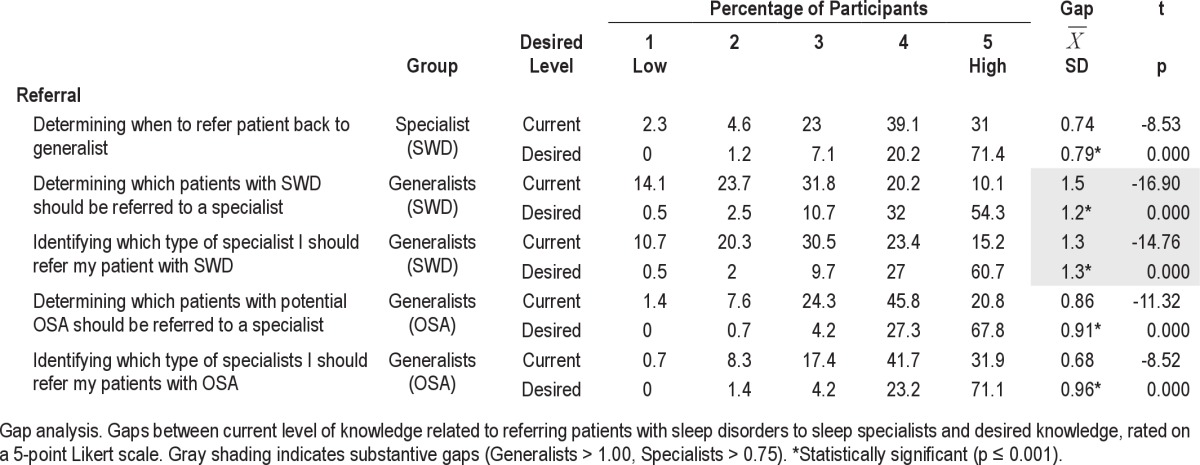

The Healthcare Team: Roles and Value

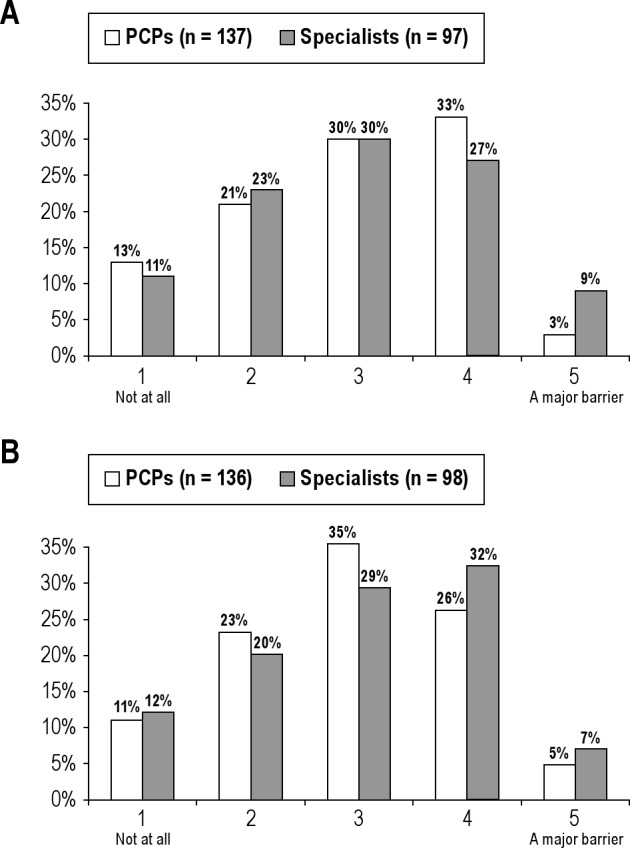

Healthcare team roles and responsibilities regarding OSA and SWD were described as unclear. Participants in both studies reported a lack of clarity about generalists' roles and responsibilities in regards to sleep disorders, with respect to which patients to refer to a sleep specialist, when referral was indicated, and to whom they should refer. This was particularly true of SWD, with less uncertainty related to OSA referrals (Table 5). In the SWD study, 66% of generalists and 66% of specialists described lack of role clarity as a barrier to optimal patient care (Figure 1A), as well as lack of coordination between generalists and specialists in treatment and management of SWD patients (generalists 66%, specialists 68%; Figure 1B). They described managing sleep disorders in isolation: 38.5% of generalists reported not referring to specialists for SWD.

Table 5.

Referral of patients with sleep disorders

Figure 1. Generalist-specialist barriers to coordinated, interprofessional care.

(A) Lack of role clarity as a barrier. (B) Lack of coordination as a barrier.

A majority of generalists did not recognize sleep medicine as a specialty, characterizing it as a poorly defined area of expertise. Furthermore, all participant groups reported a lack of uniformity in training for sleep specialists, further hindering their full recognition of sleep medicine as a credible subspecialty.

“I don't think they [generalists] see sleep as a unifying subspecialty. Someone may have snoring, they don't see it as a referral to a sleep lab as they would for someone with insomnia or restless leg syndrome.”

—Specialist

A majority of participants in both studies questioned whether specialists know much more than generalists about sleep disorders; and perceived a lack of value for patients in referring to specialists and sleep centers. Thus, only a minority of generalists reported referring patients to a limited group of sleep specialists.

“I find it somewhat difficult to diagnose OSA and the experts don't do much better. I think they over-diagnose.”

—Generalist

Generalists further expressed reluctance to refer patients to sleep specialists because they perceived that specialists assess and diagnose but do not treat or manage OSA patients.

“It seems that the emerging group of sleep specialists are more than willing to do the test and make the diagnosis, but not to follow with the treatment, compliance, etc. Specialists make the money and leave the hard stuff for the primary care physician.”

—Generalist

Sleep laboratories were also viewed with some skepticism:

“And there are a lot of shabby labs, some of them run by medical device companies.”

—Generalist

Because of the perceived lack of value of sleep lab reports, generalists expressed reluctance to refer patients to sleep laboratories. Since generalists were not convinced of the value of sleep laboratory studies, they described difficulties in convincing patients of the importance of such testing.

DISCUSSION

Sleep disorders—including both obstructive sleep apnea and shift work disorder—were unrecognized and/or not prioritized by generalists. Few generalists reported adequate knowledge in the area, characterizing care of patients with poor sleep as not urgent, frustrating, and de-motivating—attitudes that contributed to under- and misdiagnosis, under- and mistreatment, and stigmatization of patients with these low priority conditions. In 2002, 90% of generalists surveyed evaluated their knowledge of sleep disorders as fair or poor,9 as compared to 5.5% in the OSA study and 35.2% in SWD study. This study also demonstrated a shift in this knowledge gap, as only 20% of generalists questioned sleep disorders as a real diagnosis, with large gaps identified not only by generalists but also by specialists. Findings described in the results of these two studies suggest that there have been gains in the past seven years, yet much remains to be done in primary medical, specialty, and public education.

The role of specialists in sleep disorders care was questioned by generalists in these studies. This reiterates the examination of 69 qualified pulmonologists' expertise carried out in 1998,19 which found poor performance when asked to evaluate non-pulmonary sleep disorder cases. At that time, chest physicians themselves expressed a need for more formal training in sleep disorders. Current findings suggest that this remains a pressing need, with lack of qualified experts resulting in lack of interdisciplinary support for generalists in the care of their sleep disorders patients as well as generating lack of credibility for the sleep disorders specialty. Yet the value of this approach is not evident to the generalists who are often the first contact of patients with sleep disorders.

There is evidence of positive impact of a functional inter-professional healthcare team upon patient healthcare outcomes and system processes.20 Inter-professional collaboration (IPC) requires shared purpose, responsibility and goals, coordinated efforts, interdependency, and recognition of the value of each team members and commitment to the value of team-based care.21,22 The Institute of Medicine 2003 report on education in the health professions23 identifies the need for cooperation, communication, and integration of healthcare. Inter-professional education provides promise for development of such interdisciplinary care.24,25 Findings of these studies suggest the fundamental importance of addressing issues around interdependency and recognition of inter-professional value.

The importance of addressing the perception of sleep medicine is recognized within the sleep medicine community, in terms of credibility in demonstrating added value of sleep medicine within the larger medical community, and in terms of increasingly competitive and scarce funding for graduate medical education positions in sleep medicine.26 The Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommended a multidisciplinary approach to the care of OSA, including primary and specialist care, as well as other sleep resources.13 The American Thoracic Society has identified core competencies to guide sleep disorder competencies in pulmonary fellowship training programs. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has identified the importance of addressing these challenges in the medical community as a whole, to better establish the subspecialty of sleep medicine, particularly in the face of challenges posed by sleep therapists who might further impact the credibility of sleep physicians.27

Performance improvement initiatives are required that will address not only knowledge and skill in diagnosing and managing sleep disorders, but also attitudinal and team issues. Such initiatives would need to be clinically based in order to result in translation of information into actual practice, and would need to be iterative in order to continue to build and improve care of patients with sleep disorders.

Challenges have been identified in the interdisciplinary care of patients with sleep disorders

Educational programs on sleep medicine should be designed and provided to primary care generalist physicians. These should include information about when referral to sleep specialists may be of benefit and the reasons for this.

Sleep medicine training programs should include methods of integrating care with and providing useful consultation to primary care generalists.

Since sleep disorders such as OSA and SWD are chronic diseases requiring long-term follow-up and management, the importance of continuing care must be part of the educational process for patients, generalists and sleep specialists.

Performance improvement initiatives that address attitudes and team roles and responsibilities are needed.

Development of a recognized, credible, competent, specialist pool is required to support excellent primary care.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Results are based on self-report, introducing the possibility of bias due to erroneous self-assessment. However, the objective of this research was to assess subjects' perceptions of gaps, barriers, and attitudes, which can only be gathered through self-report. In this study, triangulation of findings across two disorders, two subject groups, focus groups, interviews, and survey data was used to strengthen the trustworthiness of the findings. In addition, it is possible that those who participated in our surveys may differ systematically from those who did not respond.

CONCLUSION

Knowledge, skill, and attitudinal challenges and gaps have been identified in primary care of patients with sleep disorders, resulting in sleep disorders being underdiagnosed, undertreated, stigmatized, and under-prioritized. Challenges in understanding and incorporation of the interdisciplinary team, and in particular, enhancing the role and value of the sleep specialist to the primary care community, for optimal care were also identified, impeding the contribution of sleep specialists to patient outcomes. Performance improvement initiatives are needed that address generalist knowledge and competence in providing care of patients with sleep disorders as well as competence in collaborating in an interdisciplinary team. Sleep medicine itself must also address gaps in its own training and practice as well as misconceptions of others.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Cephalon Inc. AXDEV Group Inc. received two unrestricted educational contracts to carry out this research (2007, 2008). Dr. Castriotta has received research support from Cephalon, Inc. Dr. Malhotra has received a grant from Cephalon, Inc. Dr. Landrigan has received research support from an unrestricted grant from Cephalon, Inc. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our appreciation for the contributions of the physicians and patients who participated in this study. We would like to thank Martin Dupuis, M.A., Biagina-Carla Farnesi, M.Sc., Genevieve Myhal, Ph.D., and Kayla Cytryn, R.N., Ph.D., Performance Optimization Associates, AXDEV Group, who were instrumental in carrying out this research. We would also like to express our appreciation of Elaine Turner, Project Coordinator, also from AXDEV Group, and Colleen Connor, Web/Database Coordinator, Office of Continuing Medical Education of the University of Virginia School of Medicine for their invaluable support. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the American Thoracic Society, the New Jersey Academy of Family Physicians, Office of Continuing Medical Education of the University of Virginia School of Medicine, and University of Wisconsin Office of Continuing Professional Development for their support and assistance in recruitment for the online surveys.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Washington: Institute of Medicine; 2006. [Accessed July 8, 2009]. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/CMS/3740/23160/33668.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sleep in America National Sleep Foundation. Washington: National Sleep Foundation; 2008. [Accessed July 8, 2009]. Sleep in America Poll. Available at: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/site/c.huIXKjM0IxF/b.3933533/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks S, Dinges DF. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:519–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiestand DM, Goldman M, Phillips B. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in the US population. Chest. 2006;130:780–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michigan Lung and Critical Care Specialists. Michigan: Michigan Lung and Critical Care Specialists; [Accessed February 6, 2009]. Shift Work Sleep Disorder. Available at: http://omlcc.com/SWSD.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The international classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Presser HB. Job, family, and gender: Determinants of nonstandard work schedules among employed Americans in 1991. Demography. 1995;32:577–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Walsh JK, Roth T. Shift work sleep disorder: prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep. 2004;27:1453–62. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papp KK, Penrod CE, Strohl KP. Knowledge and attitudes of primary care physicians toward sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep Breath. 2002;6:103–9. doi: 10.1007/s11325-002-0103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens JA. The practice of pediatric sleep medicine: results of a community survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E51. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kryger MH, Walid R, Manfreda J. Diagnosis received by narcolepsy patients in the year prior to diagnosis by a sleep specialist. Sleep. 2002;25:36–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavie P. Sleep medicine - time for a change. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Jr, et al. Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterji M. Evidence on “what works”: an argument for extended-term mixed method (ETMM) evaluation designs. Educ Res. 2005;34:14–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caruso C, Waters TR. A review of work schedule issues and musculosketal disorders with an emphasis on the healthcare sector. Ind Health. 2008;46:523–34. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.46.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuendorf KA. The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips B, Collop N, Goldberg R. Sleep medicine practices, training, and attitudes: a wake-up call for pulmonologists. Chest. 2000;117:1603–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johanson LS. Interprofesssional collaboration: Nurses on the team. Medsurg Nurs. 2008;17:129–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):116–31. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grenier AC, Knebel, editors. Health professions education: a bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [Accessed November 1, 2010]. Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit Board on Health Care Services. Institute of Medicine. Available at http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: an emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):8–20. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD002213. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quan SF. Sleep medicine and graduate medical education - Prospects for the future. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kushida CA. AASM President's viewpoint: planning for a challenging yet promising future. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:301–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]