Abstract

Current understanding of the association between household air-pollution (HAP) and cardiovascular disease is primarily derived from outdoor air-pollution studies. The lack of accurate information on the contribution of HAP to cardiovascular events has prevented inclusion of such data in global burden of disease estimates with consequences in terms of health care allocation and national/international priorities. Understanding the health risks, exposure characterization, epidemiology and economics of the association between HAP and cardiovascular disease represents a pivotal unmet public health need. Interventions to reduce exposure to air-pollution in general, and HAP in particular are likely to yield large benefits and may represent a cost-effective and economically sustainable solution for many parts of the world. A multi-disciplinary effort that provides economically feasible technologic solutions in conjunction with experts that can assess the health, economic impact and sustainability are urgently required to tackle this problem.

Keywords: Air-pollution, cardiovascular disease, particulate matter, urbanization, diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Most of the world’s population is exposed to some level of air-pollution owing to the ubiquitous nature of this pollutant. In low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), such exposure is often extreme with levels of both indoor and outdoor air pollution vastly exceeding levels seen in high-income countries. Household sources of air-pollution are the norm in many parts of the world with over half of the world’s population estimated to be exposed to fine particulate matter (PM) (< 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter or PM2.5) in their own homes as a consequence of using biomass fuels such as wood, charcoal, and animal/crop residues for cooking, lighting, and heating. The magnitude of exposure, when one takes into account, exposure intensity, time spent indoors (which is often far more than time spent outdoors) and the number of individuals exposed, results in a far greater contribution of household-air pollution (HAP) to global particulate matter exposure than any other source. Indoor and outdoor air-pollution mainly through household sources ranked as the 10th and 13th leading causes of mortality in the 2001 WHO Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Report and collectively easily rank within the top five risk factors for global mortality [1]. Such estimates will however still continue to represent an under-estimate, given the pervasive ominipresent nature of this risk factor, exposure through the life-cycle of an individual at doses that are orders of magnitude higher than ambient outdoor levels and finally the fact that this risk factor preferentially impacts disadvantaged and vulnerable segments of the population including women and children. The lack of inclusion of the HAP contribution to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and death may represent an additional factor contributing to the under-appreciation of its contribution towards GBD estimates. Understanding the exposure characteristics, epidemiology, economics and CVD consequences of HAP represents a pivotal unmet public health need. Interventions to reduce exposure to HAP are likely to yield large benefits to CVD and may represent a cost-effective and economically sustainable solution.

MAGNITUDE OF THE HAP PROBLEM AND EXPOSURE-RESPONSE FUNCTION

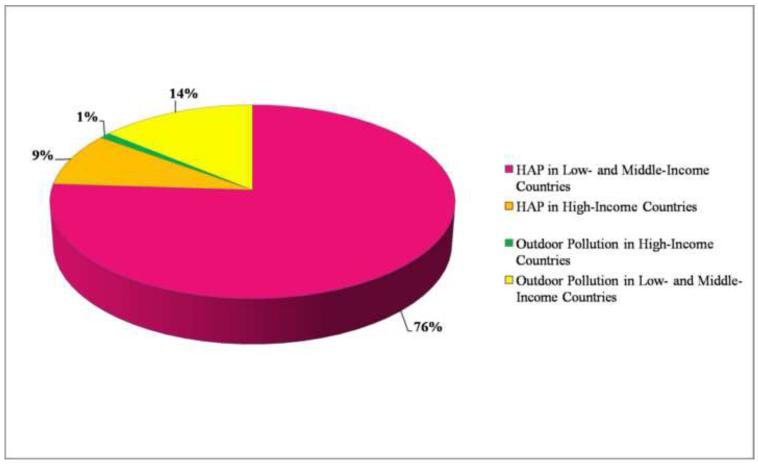

It has been estimated that approximately 75% of all PM air pollution is of indoor origin originating mainly in LMIC (Figure 1) [2,3]. An estimated 3 billion people globally or 50% of the world population still uses biomass fuels for energy needs that include cooking, heating and light [3]. The vast majority of HAP thus emanates from combustion of biomass fuels including wood, charcoal, crop residues and dried animal dung [4-7]. In the year 2000, pollution predominantly from biomass combustion was estimated to contribute to an estimated 1.6 million premature deaths per year worldwide, representing 2–3% of the global disease burden [2]. Previous GBD estimates on HAP related mortality only used risk estimates attributable to COPD, lung cancer and acute lower respiratory infection, three disease entities for which there is strong evidence of an association with exposure [1,8]. Recently a better understanding of exposure response relationship between inhaled particulate matter and CVD end-points has emerged [9,10]. These analyses juxtaposed studies in outdoor air-pollution and studies with active smoking to include a wide range of exposure levels. The results suggest a log-linear relationship, with a robust effect at low doses typically encountered with outdoor air-pollution studies with a flattening of the dose response at the highest exposure levels [9,11]. Although exposure estimates encountered with HAP are highly variable, mean exposure estimates from HAP correspond to the portion of particulate matter exposure-response relationship curve for which there is a paucity of data (1-20 mg/m3, the so called “exposure-gap”) as it straddles levels seen typically with active smoking and those seen with outdoor air-pollution [12]. HAP levels typically encountered in LMIC are several orders of magnitude higher than ambient out-door levels in the same geographic location contributing to steep indoor-outdoor gradients. For instance mean 24-hour PM10 levels between 200-2000 μg/m3 are quite common. Peak exposures of >30,000 μg/m3 during periods of cooking with exposure to low-efficiency combustion of biomass fuels have been reported [4,5,13]. These levels exceed ambient outdoor levels even in the most polluted outdoor urban environments [14, 15]. There is currently no good reason to believe that the dose response relationships between HAP and CVD outcomes will be any different (lower) than the exposure-response relationship observed with outdoor air pollution. Thus, it is highly plausible that exposure to HAP may enhance the susceptibility to CVD in addition to the already acknowledged effects on pulmonary/infectious diseases. Even if the relative risk for these separate mortality causes are similar and/or compete, given the fact that CVD represent the leading global causes of death and disability, the true GBD mediated by air-pollution (both indoor and outdoor) may far exceed prior estimates [16,17]. Efforts to quantify population attributable risk associated with air-pollution will require new integrated approaches that take into account the continuum of HAP and outdoor-air pollution and the burgeoning contribution of cardiovascular disease. The WHO burden of disease document expected in 2012 will focus on more than 220 diseases and injuries and more than 43 risk factors for 21 regions of the world. Environmental risk factors specifically being addressed in the GBD document include urban ambient air pollution, HAP, passive smoking/environmental tobacco smoke, food contamination (biological and chemical) and unsafe water, sanitation, hygiene (biological and chemical). The overall burden of disease is assessed using the disability-adjusted life year (DALY), a time-based measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality and years of life lost due to time lived in states of less than full health.

FIGURE 1.

Estimates of global exposure to particulate matter and the relative contribution of indoor and outdoor sources. Reproduced with permission from Smith, K.R. Fuel Combustion Air Pollution. Exposure and Health: the situation in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Energy and the Environment 18; 529-566, 1993.

Two approaches have been used to estimate burden of disease attributable to HAP. A fuel based approach uses the prevalence of fuel use as an exposure surrogate, odds ratios for diseases, and combines this with disease specific morbidity and mortality. This methodology is prone to systematic underestimation on account of limiting the estimates to select diseases (e.g. respiratory disease, as these have the best relative-risk estimates) and to specific population groups and to segments of the population for whom exposure-risk estimates are available (e.g. urban populations). Known relationships between mortality and morbidity for specific diseases in each age group are then used to calculate years of life lost and disability-adjusted life years lost. In practice, adequate estimates of relative risk with HAP secondary to biomass fuels are only available for women and children under 5 years and these preferentially drive calculations of population-attributable risk [4,8]. Cardiovascular event rates for all those exposed and susceptible are not factored at all into these calculations to date. Thus based on a fuel based approach, the global burden of disease is grossly underestimated. The pollutant-based approach uses exposure-effect estimates in conjunction with current rates of mortality and morbidity. The availability of risk-estimates across the spectrum of outdoor air-pollution (at the lower end) to active cigarette smoking (at the high end) may provide the basis for re-calculation of risk estimates in various indoor environments where such outcome data is not available. The inclusion of cardiovascular events across the entire dose range of exposure in the estimation of true burden of disease may result in improved estimates of GBD. Nonetheless, there are still numerous limitations and challenges beginning with the fact that there are virtually no studies that directly link HAP exposure with CVD events and it could be argued that owing to major differences in the types of pollutants seen with HAP, that these effects may not be readily extrapolated to the exposure-response curves from other sources. Considerable limitations also exist for instance in estimating exposure estimates in rural settings in high-income countries, where recourse to highly simplified models that divide the population into specific and defined environmental settings juxtaposed with exposure levels and duration of time spent to provide burden of exposure.

CURRENT UNDERSTANDING OF CARDIOVASCULAR EFFECTS OF HAP

Studies of air-pollution traditionally have focused on exclusive outdoor and indoor environments for legitimate reasons that range from the differential nature of pollutants, their sources and the populations exposed. Studies on outdoor air-pollution have vastly outnumbered studies on HAP as these have been typically conducted in affluent industrialized countries where HAP is not much of a problem [17]. In contrast studies on HAP have lagged behind as this has been traditionally a problem of impoverished societies. There is convincing evidence that exposure to biomass combustion increases the risk of a variety of respiratory diseases in both children and adults including COPD, lung cancer and asthma [4]. In contrast to the level of evidence with pulmonary disease there is a paucity of data of association between cardiovascular disease and HAP due to biomass fuel use. With rapid urbanization of many emerging economies, the dichotomization into indoor and outdoor air pollution is becoming harder to justify as both co-exist in many rapidly urbanizing societies and may influence each other. The risk factor profiles of individuals in these same environments is also rapidly changing with a high prevalence of traditional risk factors such as obesity, inactivity, western diet that has previously been shown to interact with air-pollution effects [11,18,19]. Moreover many of these countries are experiencing an unprecedented epidemic of chronic diseases including CVD and diabetes. Given the pervasive nature of exposure to both types of pollutants occurring through the life-span of many individuals and the fact that individuals don’t dichotomize their existence into indoor and outdoor living, there is a compelling case to study air-pollution as a continuum and to document these effects as a composite risk factor. Table 1 summarizes most of the studies to date that have examined the relationship between exposures to HAP and limited cardiovascular surrogate variables. A growing body of evidence has implicated inflammatory responses to diet and environmental factors as a key mechanism that help explain the emerging epidemic in diabetes and cardiovascular disease [20,21]. Both genetic and environmental factors undoubtedly play a role although the role of the physical and social environment in determining susceptibility appears to be critical. Non-traditional factors such as HAP may provide low level synergism with other dominant factors in accelerating propensity for type 2 diabetes. The societal and human costs of this link, if it can be proven would add to the burden of disease estimates and the economic costs associated with HAP.

Table 1.

List of studies examining HAP sources and their effects of CVD surrogates

| Authors | Population | Subject Location | Exposures | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCracken et al. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Nov;119(11):1562- 8. Epub 2011 Jun 13 |

Randomized trial of a stove intervention that reduces wood smoke exposure (n=49) versus open fire (n=71) on ST-segment depression and heart rate variability (HRV). Before-and-after comparison in 55 control subjects who received stoves after the comparison trial. Average ST-segments below −1.0 mm, regardless of slope was assessed. |

Southern highlands of Guatemala |

PM2.5 exposure means were 266 and 102 μg/m3 during the trial period in the control and intervention groups, respectively. The cookstove group used this for 293 days on average prior to end-points. |

The mean ST-segment was ≅ 0.10 mm lower, among control group than among the intervention group. In the before/after study mean ST-segment was higher and rate of depression/person-day was reduced to < half after they received the chimney stove |

| Baumgartner et al. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Oct;119(10):1390- 5.. |

Prospective cohort study of 280 women ≥ 25 years of age living in rural households using biomass fuels with assessment of 24- hr personal integrated gravimetric exposure to fine particles < 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5) in winter and summer.. |

Yunnan, China | Personal average 24-hr exposure to PM2.5 ranged from 22 to 634 μg/m3 in winter and from 9 to 492 μg/m3 in summer |

A 1-log-μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 exposure was associated with 2.2 mm Hg higher SBP [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.8 to 3.7; p = 0.003]. The effect estimates were more pronounced in women >50 years. |

| Allen et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 1;183(9):1222-30 |

Randomized crossover study of 45 healthy adults exposed to consecutive 7-day periods of filtered and non-filtered woodsmoke air |

British Columbia, Canada |

Indoor air filters reduced indoor fine particle concentrations by 60% (from 11.2 mg/m3 with HEPA off to 4.6 mg/m3 with HEPA on) |

Endothelial function using peripheral tonometry improved with air-filtration. CRP levels tended towards improvement |

| Dutta et al. Indoor air 2010 Indoor Air. 2011 Apr;21(2):165-76. |

244 biomass fuel-using and 236 control women across 10 villages who cooked with liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) |

West Bengal, India |

The 8-h mean concentration of PM10 in cooking areas of biomassusing households was 276 ± 108 (s.d.) μg/m3 in contrast to 97 ± 36 μg/m3 in LPGusing households. The mean PM2.5 concentration was also significantly higher in biomass- using households (156 ± 63 vs. 52 ± 27 μg/m3 in LPG using households |

Increased hypertension (29.5 vs. 11.0%, p<0.05), elevated oxLDL, platelet P-selectin expression and aggregation, raised aCL IgG and reactive oxygen species |

| Emiroglu et al. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Oct;23(5):420-4 |

39 female exposed to bio-mass fuel (group 1) and 31 control subjects. Pulmonary function (PFT), and echo assessment of right ventricular volume, diameters and pulmonary artery pressures. BNP levels were measured and correlated to TTE findings |

Rural area in Turkey |

Group 1: 39 females underwent 167 ± 107 h-year exposure to firewood and dried cow dung smoke Group 2: 31 normal female subjects |

Obstructive and restrictive findings on PFTs with increased RV volumes. Changes in PFTs correlated with PA pressures. BNP levels were elevated |

| Brauner at al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Feb 15;177(4):419- 25 |

21 nonsmoking couples in a randomized, crossover study with two consecutive 48-hour exposures to either particle-filtered or nonfiltered air. Microvascular flow measured by digital tonometry |

Copenhagen, Denmark |

Two consecutive 48-hour exposures to either particle filtered or non- filtered air (2,533– 4,058 and 7,718– 12,988 particles/cm3, respectively) in their homes |

Improvement in microvascular flow with air-filtration of indoor air |

| Barregard et al. Occup Environ Med. 2008 May;65(5):319-24. |

13 subjects exposed to clean air and then to wood smoke in a chamber during 4-hour sessions, 1 week apart |

Goteborg, Sweden | The mass concentrations of fine particles at wood smoke exposure were 240– 280 mg/m3, and number concentrations were 95 000–180 000/cm3, about half of the particles being ultrafine |

Increase in exhaled nitric oxide (3-hours post) and malondeladehyde levels (increased immediately and after 20 hours) |

| McCracken et al. Environ Health Perspect. 2007 Jul;115(7):996- 1001. |

Randomized trial of improved cookstove in Guatemala (23 villages at 2,200–3,000 m elevation in San Marcos) to reduce indoor emissions. Women > 38 years randomized to chimney woodstove intervention (49 subjects) or traditional open wood fire (71 subjects) |

Guatemala | Daily average PM2.5 exposures 264 and 102 μg/m3 in control and intervention groups |

Improved stove intervention associated with 3.7 mm Hg lower SBP and 3.0 mm Hg lower DBP compared with controls |

| Barregard et al. Inhal Toxicol. 2006 Oct;18(11):845-53 |

13 subjects were exposed to wood smoke and clean air in a chamber during two 4-h sessions, 1 wk apart |

Goteborg, Sweden | Mass concentrations of 240-280 μg/m3 |

Exposure to wood smoke increased serum amyloid A, factor VIII and the factor VIII/vWF ratio, increased urinary 8- iso-prostaglandin F2α |

HAP ASSOCIATED CVD: A CALL FOR ACTION

To pin down the CVD impact of HAP and in order to effectively use interventions to mitigate risk secondary to air-pollution there is an urgent need for research in this area. A pre-requisite for all research proposals in general and for studies in HAP in particular is the need to balance cost with necessity for information. Research priorities in HAP can be categorized into five broad areas outlined in Table 2. There is a level of synergism between all of these objectives and each of these ideally must be coupled to the other objectives. (1) Exposure assessment: Cost-effective techniques for exposure assessment that allow longitudinal analysis of HAP in concert with outdoor levels and how they influence each other. Studies that provide better source characterization and evidence of efficacy of interventions such as cook stoves are very much required. (2) Epidemiology: Large studies that track exposure to HAP with cardiovascular outcomes and provide a better understanding of the dose response relationship of HAP. Studies that lead to elucidation of poorly understood socio-economic and cultural variables that modulate risk susceptibility and exposure outcomes. (3) Interventions: Low cost engineering approaches (improved stoves, fuels and ventilation) and educational interventions that provide “no-cost” means to reduce exposure to both sources. (4) Economics: This should provide much needed information on the cost-impact of improvements in HAP through reducing biomass fuel use on national productivity, GDP and price. Governments and agencies world-wide must have a compelling rationale to effect change and such analysis will need to take into account, not only the cost of innovation but the cost-savings as a consequence of improvement in air-quality at a regional and national level. (5) Mechanistic studies: Studies that elucidate critical gaps in our information regarding cardiovascular health effects of HAP in locations where the levels of exposures are within the exposure gap (1-20 mg/m3) [12]. These studies could utilize commonly used surrogates that have known value in predicting future risk for events.

TABLE 2.

Research Priorities in Household Air-Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD).

| Exposure Assessment Studies |

|

| Epidemiologic Studies |

|

| Mechanistic Studies Linking Cardiovascular Health with Exposure |

|

| Technological and Educational Interventions |

|

| Economics of Interventions and Health Care Costs |

|

A multi-disciplinary team coalition that comprises cardiovascular health specialists, epidemiologists, exposure-assessment experts and economists would be an example of a model collaborative unit that can address compelling benefits in HAP. Such a team can be embedded with an intervention targeting. The new Global Alliance for Clean Cook stoves, a public–private partnership led by the UN Foundation, was launched to address the issue of biomass fuel use for cooking worldwide [22]. The alliance was announced in September 2010 and is meant to replace traditional methods of cooking on open fires or dirty stoves that consume biomass fuels with clean burning stoves. There are relatively few interventions that may be as cost-effective as intervention on HAP where introduction of improved biomass stoves or use of liquefied petroleum gas stoves may cost as little as $50-100/DALY. Considering the fact that interventions to improve outdoor air-quality are far more expensive, costing over $1000/DALY, this investment is a veritable bargain. In the ultimate analysis investment in mitigating HAP may have tremendous benefits for improving global health in an unprecedented manner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIEHS Grants R01ES017290, R01ES015146 and RO1ES019616 to SR and the EPA Supported Great Lakes Center for Environmental Research (GLACIER) to SR and RB. The authors wish to thank Geoffrey Gatts for his excellent editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smith KR, Mehta S, Maeusezahl-Feuz M, editors. Indoor air Pollution from household use of solid fuels: comparative quantification of health risks. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]; Ezzati M, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected risk factors.

- [3].Smith KR, Mehta S, Maeusezahl-Feuz M. Environmental and occupational risk factors. World Health Organization; Indoor air pollution from household use of solid fuels. Available at: http://www.who.int/publications/cra/chapters/volume2/part2/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Torres-Duque C, Maldonado D, Perez-Padilla R, Ezzati M, Viegi G. Biomass fuels and respiratory diseases: a review of the evidence. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(5):577–590. doi: 10.1513/pats.200707-100RP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ezzati M, Kammen DM. The health impacts of exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in developing countries: knowledge, gaps, and data needs. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(11):1057–1068. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lin HH, Murray M, Cohen T, Colijn C, Ezzati M. Effects of smoking and solid-fuel use on COPD, lung cancer, and tuberculosis in China: a time-based, multiple risk factor, modelling study. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1473–1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61345-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Smith KR, Mehta S. The burden of disease from indoor air pollution in developing countries: comparison of estimates. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2003;206(4-5):279–289. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pope CA, 3rd, Burnett RT, Krewski D, Jerrett M, Shi Y, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Cardiovascular mortality and exposure to airborne fine particulate matter and cigarette smoke: shape of the exposure-response relationship. Circulation. 2009;120(11):941–948. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.857888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pope CA, Burnett RT, Turner MC, Cohen A, Krewski D, Jerrett M, Gapstur SM, Thun MJ. Lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality associated with ambient air pollution and cigarette smoke: shape of the exposure-response relationships. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(11):1616–1621. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC, Jr., Whitsel L, Kaufman JD. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2331–2378. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith KR, Peel JL. Mind the gap. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118(12):1643–1645. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1078–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang S, Zhao Y, Chen G, Wang F, Aunan K, Hao J. Assessment of population exposure to particulate matter pollution in Chongqing, China. Environ Pollut. 2008;153(1):247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kulshreshtha P, Khare M, Seetharaman P. Indoor air quality assessment in and around urban slums of Delhi city, India. Indoor Air. 2008;18(6):488–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2008.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mestl HE, Aunan K, Seip HM. Health benefits from reducing indoor air pollution from household solid fuel use in China--three abatement scenarios. Environ Int. 2007;33(6):831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fuster V, Kelly BB, Medicine Io, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Preventing the Global Epidemic of Cardiovascular Disease. Meeting the Challenges in Developing Countries Book; Washington (DC). 2010/10/15.2010. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Brook RD, Rajagopalan S. Particulate matter air pollution and atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12(5):291–300. doi: 10.1007/s11883-010-0122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brook RD, Rajagopalan S. Particulate matter, air pollution, and blood pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(5):332–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sun Q, Yue P, Deiuliis JA, Lumeng CN, Kampfrath T, Mikolaj MB, Cai Y, Ostrowski MC, Lu B, Parthasarathy S, Brook RD, Moffatt-Bruce SD, Chen LC, Rajagopalan S. Ambient air pollution exaggerates adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Circulation. 2009;119(4):538–546. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.799015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Brook RD, Jerrett M, Brook JR, Bard RL, Finkelstein MM. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and traffic-related air pollution. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(1):32–38. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815dba70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cleancookstoves.org [Internet] Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves; Washington, DC: [cited 2012 March 12]. Available from: http://cleancookstoves.org. [Google Scholar]