Abstract

Wishful thinking (WT) implies the overestimation of the likelihood of desirable events. It occurs for outcomes of personal interest, but also for events of interest to others we like. We investigated whether WT is grounded on low-level selective attention or on higher level cognitive processes including differential weighting of evidence or response formation. Participants in our MRI study predicted the likelihood that their favorite or least favorite team would win a football game. Consistent with expectations, favorite team trials were characterized by higher winning odds. Our data demonstrated activity in a cluster comprising parts of the left inferior occipital and fusiform gyri to distinguish between favorite and least favorite team trials. More importantly, functional connectivities of this cluster with the human reward system were specifically involved in the type of WT investigated in our study, thus supporting the idea of an attention bias generating WT. Prefrontal cortex activity also distinguished between the two teams. However, activity in this region and its functional connectivities with the human reward system were altogether unrelated to the degree of WT reflected in the participants’ behavior and may rather be related to social identification, ensuring the affective context necessary for WT to arise.

Keywords: cognitive bias, functional magnetic resonance imaging, psychophysiological interaction, selective attention

For what a man more likes to be true, he more readily believes (Francis Bacon, 1561–1626).

INTRODUCTION

Human reasoning and decision-making are subject to distortions, which may originate in a variety of different reasons, ranging from the application of simple heuristics (Goldstein and Gigerenzer, 2002) to more complex groupthink (Kerschreiter et al., 2008). These distortions are not necessarily irrational. Under some circumstances, simple heuristics can lead to more accurate inferences than strategies that arise from considerable knowledge about a situation (Goldstein and Gigerenzer, 2002). Also, Zábojník (2004) developed a model that explains why most individuals legitimately believe that they are above average in various skills and abilities. According to this model, individuals test and improve their abilities until they are reasonably favorable, and thus, above average. Moreover, skills and abilities are not always normally distributed, leading occasionally to the phenomenon that >50% of the individuals in a population score indeed above average. These considerations show that some biases are quite rational—but others are not.

Francis Bacon's observation presaged work on a particularly pernicious systematic irrational bias, the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of desirable events and underestimate the likelihood of undesirable events. This cognitive bias has been called wishful thinking (WT, McGuire, 1960).1 In contrast to heuristics and the type of rational estimations of own capacities described before, WT originates in the application of individual preferences that are linked to affective experiences.

WT biased beliefs and decision-making have reliably been observed in many different contexts, especially when events are of personal relevance and people thus feel personally invested in the outcomes of their predictions (Babad, 1987; Granberg and Holmberg, 1988). Biased predictions may work to maximize the anticipated reward or the hedonic valence of an expected outcome. WT has been documented whether the outcomes apply directly to the decision maker or they apply to someone with whom the decision maker identifies (McGuire, 1960; Babad and Katz, 1991; Price, 2000). The particular case of WT for others is in line with research on social identity theory, which has shown that individuals generally prefer ingroup members over outgroup members (Tajfel et al., 1971) and that they display a need for a positive social identity (Turner and Onorato, 1999). Overestimating the likelihood of positive events for other people or groups with whom we identify therefore may increase the experienced positivity of our own social identity, and, consequently, the hedonic valence of a predicted outcome, thus functioning as an affective reward. Evidently, WT is not a rare but a rather common phenomenon.

The concrete mechanisms underlying WT are still unknown. Krizan and Windschitl (2007) put forth three different stages at which WT could arise. First, at an early processing stage individuals could selectively attend to existing situational cues. Attentional deployment in WT may work in the sense of a confirmation bias, making us attend to supporting evidence for what we desire and neglect contradictory evidence. Such a mechanism would consequently serve the WT effect. Alternatively, WT could be generated by selective interpretation of available evidence, thus changing the sense of but not the access to the existing information in a situation. Attributing greater importance to the desirable than to the undesirable evidence in a situation would work in this service. Finally, a third alternative assumes WT to arise at a comparably late stage of information processing, namely at response formation. Consequently, the mechanism underlying WT could be either an attention bias, an interpretation bias, or a response bias.

Investigations of the neural correlates of wishful thinking are absent but could help identifying the mechanisms generating WT by supporting or contradicting either of these alternatives. For example, if early selective attention were at the basis of the WT effect, individuals should display WT-related activation in low-level attention-associated brain regions. Since, in the current study, the background information was presented visually, selective attention should be particularly visible in the visual cortex (e.g. Sabatinelli et al., 2007). If, on the contrary, an interpretation bias or a response bias rather than an attention bias were responsible for the genesis of WT, we would expect the implication of higher level cognitive processing areas within the prefrontal cortex (PFC) because these mechanisms would imply either evidence reevaluation (reappraisal) or attempts at cognitive regulation (e.g. Ochsner et al., 2002; Sharot et al., 2007; see also Miller and Cohen, 2001, for an extensive discussion on the importance of the prefrontal cortex for cognitive control). Additional justification for such a hypothesis comes from research on pathological gambling, which has been associated with biased cognitions leading to over-optimism and, importantly, with dysfunctions of the ventromedial PFC (Cavendini et al., 2002). Consequently, fMRI may help to reveal whether low-level attentive or higher level cognitive processes are at the origin of WT.

Moreover, because WT has been postulated to be a hedonic bias, activity in the areas supporting either of these mechanisms being at the origin of the WT phenomenon should be functionally connected to activity in the human reward system. This is because during WT people adopt expectations that they believe will yield affective rewards. Therefore, WT should recruit structures of the human reward system (including the striatum, the posterior cingulate and the amygdala; Heekeren et al., 2007; Delgado et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2009). For instance, anticipated reward, such as pleasure experienced by favorite team soccer goals (McLean et al., 2009) has been reported to go along with activation in the dorsal striatum.

We investigated the neural correlates of WT in a social identification context based on National Football League (NFL) teams with participants who were recruited based on their reports that they cared about and followed closely a particular team in the NFL. Objective background information in this task was given in the same manner for all experimental scenarios, prohibiting the possibility that observed differences between scenarios would result from a differential access to available information. Participants in the current study estimated the winning odds for different NFL teams [favorite, neutral (filler items) and least favorite] on the basis of this background information. According to identification theory, outcomes bearing on the participant's favorite team are higher in self-relevance than outcomes bearing on one's least favorite team. Brain activity was recorded in an MRI scanner while the participants gave the estimations. In line with earlier research and behavioral pilot testing, we expected that participants would overestimate the success of the favorite team with respect to the least favorite team, that is, that they would exhibit WT.

The neural correlates of WT were investigated by (i) comparing favorite to least favorite team trials, because, during WT, individuals should well distinguish between the two teams, (ii) identifying functional connectivities of these areas with other brain regions (e.g. the human reward system) and (iii) by correlating these activation and connectivity data with the extent of WT demonstrated in the participants’ behavior. The latter point is particularly important because activation and connectivity patterns differing for favorite vs least favorite team trials could otherwise be simply a sign of differential preference for or identification with the two teams without being related to WT itself.

METHODS

Participants

The study was approved by a local ethics committee (institutional review board for biological sciences at the University of Chicago). Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of Human Rights (1999). Thirteen (two female) healthy University of Chicago students were recruited via ads posted on the Internet and in university buildings. They were aged between 19 and 34 years (M = 21.8, s.d. = 3.82) and indicated high interest in the NFL [M = 5.8, s.d. = 1.63, on a scale ranging from 1 (no interest) to 7 (intense interest)]. Five participants actively practiced American football (M = 8 h/week, s.d. = 6.08 h/week) at the time of the study. All but one watched football on a weekly basis (TV or local; M = 4.5 h/week, s.d. = 3.40 h/week). Participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were not currently seeking treatment for affective disorders. Handedness was assessed with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971). Only individuals indicating ‘right’ for all items were included in the study. Participants were paid $15/h.

Setting and apparatus

MRI data were acquired on a 3T GE Signa scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a standard quadrature GE head coil. Stimulus presentation and collection of participants’ button presses were controlled by e-prime 1.1 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA) running on a PC. Participants viewed the stimuli by the use of binocular goggles mounted on the head coil ∼2 in above the participants’ eyes. Button press responses were made on two MRI-compatible response boxes. Every button corresponded to a specific number (e.g. leftmost button left hand: 1; rightmost button right hand: 0).

High-resolution volumetric anatomical images [T1-weighted spoiled gradient-recalled (SPGR) images] were collected for every participant in 124 1.5-mm sagittal slices with 6° flip angle and 24 cm field of view (FOV). Functional data were acquired using a forward/reverse spiral acquisition with 40 contiguous 4.2-mm coronal slices with 0.5-mm gaps, for an effective slice thickness of 4.7 mm, in an interleaved order spanning the whole brain. Volumes were collected continuously with a repetition time (TR) of 3 s, an echo time (TE) of 28 ms and a FOV of 24 cm (flip angle = 84°, 64 × 64 matrix size, fat suppressed).

Procedure

Upon participants’ arrival at the laboratory the nature of the experiment was explained and informed consent was obtained. Then, participants specified their favorite, neutral (team they neither liked nor disliked) and least favorite NFL teams.

Brain activity was recorded in an MRI scanner while the participants did 60 estimations (20 for each team). In each trial, participants were given background information about a single team (favorite, neutral, or least favorite). Trials for the neutral team acted as irrelevant filler trials in the current study. The background information comprised three pieces: (i) The probability of winning for the team in question if a given player played, (ii) the probability of winning if this specific player did not play and (iii) the probability that this player would actually play. Bayesian statistics permit the combination of these probabilities to determine the objective probability that the team will win the game (Petty and Cacioppo, 1981). However, in the current study, participants were not given enough time to perform exact statistics.

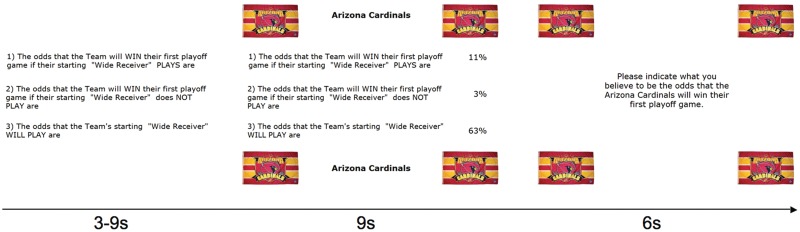

The particular probabilities used for the favorite, neutral and least favorite teams were counterbalanced across participants. In order to make the teams more salient, in every trial, the team logos appeared in each of the four corners of the computer screen with the background information presented in between (Figure 1). The participants’ task then was to specify what they believed to be the probability that the presented team would win its first playoff game given this information.

Fig. 1.

Trial sequence. In every trial, the three statements were first presented for a random time of 3, 6 or 9 s, without any indication of the corresponding probabilities and the concerned team. Next, the club banner of the concerned team appeared in all four corners of the screen and the statement-related probabilities were projected to the right of the statements. From this moment, participants had 9 s to estimate the supposed winning odds. After this, a question prompted them to indicate their probability estimate by the use of two button boxes. Participants were given 6 s to do so. Immediately after, the next trial began with the presentation of the three statements.

Before beginning the study, participants were trained on the use of two button boxes, permitting them to indicate the probability estimates, and got the occasion to go through 10 practice trials to get familiar with the task. They were informed that they might ask questions about anything that was not perfectly clear to them. After the study, the participants indicated their sympathy with the different teams on three different Likert scales. These scales asked how much they liked the teams [ranging from 1 (extremely dislike) to 7 (extremely like)], as well as how pleasant [ranging from 1 (extremely unpleasant) to 7 (extremely pleasant)] and appealing [ranging from 1 (extremely unappealing) to 7 (extremely appealing)] the teams were to them.

Data analysis

Behavioral data

Participants’ sympathy ratings for the favorite and least favorite team were contrasted with a paired samples t-test (α level of 0.05, one-tailed). In order to determine the extent of WT, for each trial, the objectively correct winning odds were subtracted from the participants’ estimates, thus yielding 60 difference scores per participant. Missing responses and outliers (estimates referring to difference scores deviating >3 s.d.'s from the mean difference score of a participant) constituted ∼5% of the data and were eliminated. A paired-samples t-test with an α level of 0.05 comparing participants’ estimates for the favorite team with the ones for the least favorite team was calculated. Given the directional nature of the hypothesis, a one-tailed test was performed.

FMRI data

Functional scans were realigned, normalized, time and motion corrected, temporally smoothed by a low-pass filter consisting of a 3-point Hamming window, and spatially smoothed by a 5-mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter, using AFNI software. Next, a percent-signal change data transformation was applied to the functional scans. Individual deconvolution analyses incorporated the generation of impulse response functions (IRFs) of the BOLD signal on a voxel-wise basis (Ward, 2001), permitting the estimation of the hemodynamic response for each condition relative to a baseline state (baseline, in our case, referred to the mean individual signal across the whole experimental session) without a priori assumptions about the specific form of an IRF. Deconvolution analyses comprised separate regressors for each time point (six included TRs, starting with the apparition of the club banners and the statement-related probabilities, i.e. the calculation process) of each experimental condition, and fitted these regressors by the use of a linear least squares model. Estimated individual percent-signal change for TRs two to six was averaged for each voxel in each condition for use in later statistical analyses. Output from the individual deconvolution analyses was converted to Talairach stereotaxic coordinate space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) and interpolated to volumes with 3 mm3 voxels.

Since WT should rely on a distinction between favorite and least favorite team trials, for each participant, three contrasts of interest were conducted for use in group-level whole-brain analyses: Percent signal change of each condition with respect to baseline as well as the differences in-percent-signal change for favorite vs least favorite team. Results were then entered into a cluster analysis with an individual voxel threshold of P < 0.01, minimum cluster connection radius of 5.2, and a cluster volume of 702 µl (corresponding to 26 active, contiguous voxels). Minimum cluster volume was calculated by a Monte Carlo simulation with 10 000 iterations, assuming some interdependence between voxels (5 mm FWHM), resulting in a corrected whole-brain P-value of 0.05. Consequently, this method corrects for whole brain volume and thus, multiple testing at the voxel level.

To get insight into the coactivations of the brain areas differing between the favorite and least favorite teams with other brain areas (including the human reward system), we entered the regions found to significantly differ between the two teams as input seeds for context-dependent functional connectivity (also called psychophysiological interaction, PPI) analyses. Analyses for each cluster were conducted separately for each team as well as for the differential activity between the two teams. These analyses tested, within a whole brain analysis, for synchronized activities with the input seed regions. The exact method adopted can be found at: http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/sscc/gangc/CD-CorrAna.html. Results were entered into a cluster analysis with an individual voxel threshold of P < 0.01, minimum cluster connection radius of 5.2 and a cluster volume of 702 µl (corresponding to 26 active, contiguous voxels).

Finally, and most importantly, we tested whether clusters displaying differential activation for the favorite and the least favorite team as revealed in the whole brain analysis were indeed related to WT and not just displaying affective preferences or differential identification with the two teams. We calculated between-subjects Spearman correlations between the differential activations in these clusters, on the one hand, and the difference in behavioral estimates for the two teams, on the other hand. We also extended this analysis to the functional connectivities: The differences (favorite vs least favorite trials) in Fisher's z correlations between seed and identified functionally connected clusters, on the one hand, were correlated with the difference in behavioral estimates for the two teams, on the other hand.

RESULTS

Behavioral data

The favorite team was more liked than the least favorite team, t(12) = 10.31, P < 0.000001 (M's = 6.5 and 2.0), and it was judged as more pleasant, t(12) = 7.66, P < 0.00001 (M's = 6.2 and 1.8), and more appealing, t(12) = 7.96, P < 0.000005 (M's = 6.2 and 2.2). More importantly, participants systematically overestimated the winning prospects for their favorite team compared with their least favorite team, t(12) = 2.13, P < 0.05 (deviations from objectively correct estimates: M's = 1.0, and −1.3, respectively), thus displaying WT. The 13 participants specified 9 different favorite teams and 8 different least favorite teams. Therefore, our results are not restricted to specific NFL teams.

Functional MRI data

Changes from baseline for both the favorite and the least favorite team included a decrease of default network activity (medial frontal and various temporal areas), but an increase in activity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and occipital areas (Table 1). Activations and deactivations for the two teams were largely overlapping, with the slight difference of larger cluster sizes and, consequently, fewer clusters for the favorite team trials.

Table 1.

Whole-brain analyses

| Contrast/Areas | Cluster volume (mm3) | Talairach coordinates |

T(12) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Favorite team vs baseline | ||||||

| B fusiform gurus, B inferior parietal lobule, B superior parietal lobule, B precuneus, B thalamus, B cingulate gyrus, B medial frontal gyrus, B superior frontal gyrus, B cerebellum | 154 332 | −1 | −32 | 30 | 9.87 | <0.0000005 |

| B superior frontal gyrus, B medial frontal gyrus | 32 778 | 1 | 42 | 17 | −8.16 | <0.000004 |

| R supramarginal gyrus, R superior temporal gyrus | 10 287 | 56 | −50 | 23 | −9.41 | <0.0000007 |

| L inferior temporal gyrus, L superior temporal gyrus, L inferior frontal gyrus, L insula | 8208 | −43 | 6 | −9 | −7.08 | <0.00002 |

| L middle temporal gyrus, L superior temporal gyrus | 6426 | −52 | −57 | 18 | −6.67 | <0.00003 |

| L cuneus, L lingual gyrus | 5184 | −11 | −86 | 2 | −7.36 | <0.000009 |

| B posterior cingulate, B cingulate gyrus | 3105 | −3 | −51 | 28 | −4.69 | <0.0006 |

| R middle temporal gyrus, R superior temporal gyrus | 2565 | 48 | −9 | −10 | −8.36 | <0.000003 |

| R middle frontal gyrus | 2376 | 42 | 28 | 30 | 6.06 | <0.00006 |

| R precentral gyrus, R inferior frontal gyrus | 2349 | 53 | 3 | 27 | 5.55 | <0.0002 |

| R inferior frontal gyrus, R insula | 2214 | 46 | 28 | −3 | −6.54 | <0.00003 |

| Lingual gyrus, R cuneus | 1053 | 19 | −89 | −3 | −6.23 | <0.00004 |

| L cingulate gyrus | 810 | −25 | −31 | 27 | −4.68 | <0.0006 |

| L posterior cingulate, L lingual gyrus | 783 | −24 | −65 | 5 | 4.46 | <0.0008 |

| R interior frontal gyrus | 729 | 27 | 11 | −13 | −4.88 | <0.0004 |

| Least favorite team vs baseline | ||||||

| B cingulate gyrus, L middle frontal gyrus, B medial frontal gyrus, B precuneus, B inferior parietal lobule, R superior occipital gyrus, L precentral gyrus | 75 060 | −6 | −31 | 39 | 9.93 | <0.0000004 |

| B medial frontal gyrus, B superior frontal gyrus, B anterior cingulate | 41 715 | 1 | 41 | 22 | −8.42 | <0.000003 |

| B thalamus, L insula, L putamen, L caudate, L lentiform nucleus | 22 896 | −8 | −13 | 0 | 6.29 | <0.00004 |

| R middle temporal gyrus, R superior temporal gyrus, R inferior frontal gyrus, R supramarginal gyrus, R inferior parietal lobule, R insula | 18 198 | 50 | −26 | 10 | −7.70 | <0.000006 |

| L superior temporal gyrus, L middle temporal gyrus, L angular gyrus, L supramarginal gyrus, L inferior parietal lobule | 11 691 | −51 | −46 | 15 | −6.54 | <0.00003 |

| L lingual gyrus, L cuneus | 6993 | −11 | −85 | 0 | −6.68 | <0.00003 |

| B posterior cingulate, B cingulate gyrus, B precuneus | 5562 | −3 | −51 | 28 | −5.82 | <0.00009 |

| R insula, R lentiform nucleus, R claustrum, R putamen, R caudate | 3699 | 29 | 13 | 11 | 5.19 | <0.0003 |

| L inferior frontal gyrus | 3591 | −38 | 27 | −4 | −7.21 | <0.00002 |

| B cingulate gyrus | 3537 | 2 | −20 | 37 | −7.05 | <0.00002 |

| R inferior frontal gyrus, R precentral gyrus | 2754 | 53 | 3 | 27 | 5.58 | <0.0001 |

| B cerebellum | 2538 | 2 | −50 | −26 | 4.44 | <0.0009 |

| R middle occipital gyrus, R inferior occipital gyrus, R fusiform gyrus | 2376 | 40 | −68 | −11 | 6.97 | <0.00002 |

| R cerebellum | 1404 | 31 | −49 | −29 | 4.78 | <0.0005 |

| R middle frontal gyrus | 1215 | 38 | 29 | 34 | 6.87 | <0.00002 |

| L parahippocampal gyrus | 945 | −23 | −36 | −10 | −4.93 | <0.0004 |

| R lingual gyrus | 945 | 18 | −86 | −7 | −5.65 | <0.0002 |

| L middle frontal gyrus | 918 | −33 | 49 | 0 | −5.96 | <0.00007 |

| B cerebellum | 783 | 0 | −66 | −25 | 4.42 | <0.0009 |

| L middle frontal gyrus | 783 | −39 | 19 | 30 | 4.82 | <0.0005 |

| L posterior cingulate, L lingual gyrus | 729 | −23 | −65 | 5 | 4.21 | <0.002 |

| Favorite team vs least favorite team | ||||||

| R superior parietal lobule, R precuneus | 1404 | 26 | −60 | 43 | 4.87 | <0.0005 |

| L inferior occipital gyrus, L fusiform gyrus | 783 | −34 | −62 | −6 | 6.73 | <0.0001 |

| L medial frontal gyrus, L superior frontal gyrus | 702 | −2 | 54 | 22 | 6.29 | <0.0001 |

All Ps are based on two-tailed testing.

B = bilateral; L = left; R = right.

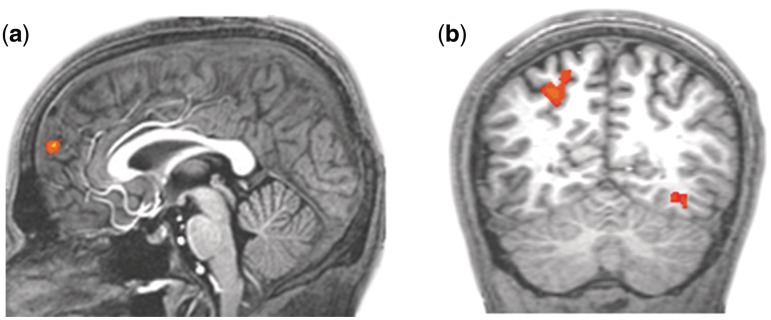

The BOLD contrast for favorite minus least favorite team revealed greater activity in (i) left medial and superior frontal gyri within the dorsomedial PFC [dmPFC; x, y, z = −2, 54, 22; t(12) = 6.29, P < 0.0001; cluster volume: 702 mm3; Figure 2a], (ii) right precuneus and right superior parietal lobule [x, y, z = 26, −60, 43; t(12) = 4.87, P < 0.0005; cluster volume: 1404 mm3; Figure 2b] and (iii) left inferior occipital and left fusiform gyri [x, y, z = −34, −62, −6; t(12) = 6.73, P < 0.0001; cluster volume: 783 mm3; Figure 2b] for the favorite team.

Fig. 2.

Areas showing differential activation for the two teams. Significantly greater activation for the favorite team as compared with the least favorite team was observed in bilateral medial and superior frontal gyri within the medial prefrontal cortex [a; Talairach coordinates (x, y, z): −2, −54, 22], right precuneus and right superior parietal lobule (b; 26, −60, 43) and left interior occipital and left fusiform gyri (b; −34, −62, −6).

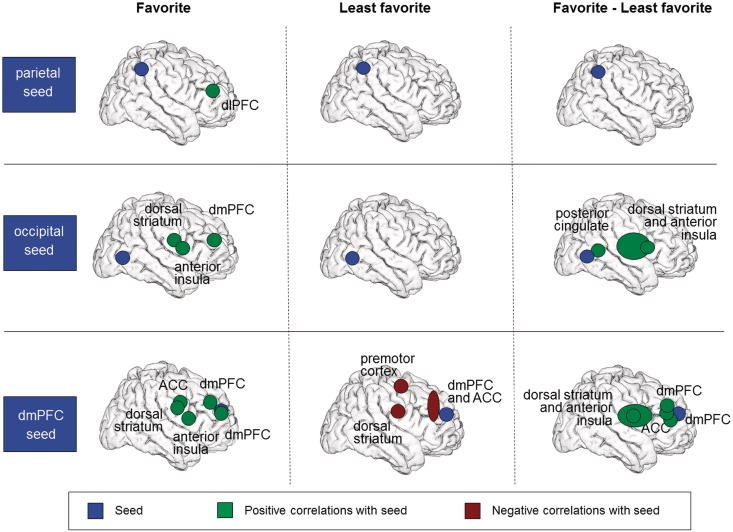

Context-dependent functional connectivity analyses

During the favorite team trials, but not during the least favorite team trials, the parietal seed cluster was functionally connected with an area in the left dlPFC (Table 2 and Figure 3). However, the parietal cluster was not functionally connected to any other brain region in our study when the differential activity between the favorite and least favorite teams was examined, thus showing that the supposed difference in coactivations of the parietal cortex and the dlPFC between the favorite and the least favorite team did not reach significance.

Table 2.

Context-dependent functional connectivity analyses

| Cluster/Contrast | Areas | Cluster volume (mm3) | Talairach coordinates |

t(12) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Parietal cluster | |||||||

| Favorite team | L middle frontal gyrus | 783 | −34 | 31 | 26 | 5.61 | <0.0002 |

| Least favorite team | –No significant connectivities | ||||||

| Favorite vs least favorite team | –No significant connectivities | ||||||

| Occipital cluster | |||||||

| Favorite team | R claustrum, R insula, R putamen, R caudate | 1728 | 30 | 3 | 18 | 8.21 | <0.000003 |

| R medial frontal gyrus | 1269 | 13 | 39 | 26 | 7.58 | <0.000007 | |

| L claustrum, L insula, L putamen | 837 | −28 | 11 | 17 | 6.74 | <0.00003 | |

| Least favorite team | –No significant connectivities | ||||||

| Favorite vs least favorite team | R putamen, R caudate, R claustrum, R insula, B thalamus | 4779 | 18 | −22 | 15 | 10.20 | <0.0000003 |

| L claustrum, L insula, L putamen | 1485 | −28 | 12 | 15 | 7.78 | <0.000006 | |

| R posterior cingulate | 891 | 20 | −53 | 4 | 4.27 | <0.002 | |

| dmPFC cluster | |||||||

| Favorite team | L caudate, L cingulate gyrus | 1593 | −11 | 7 | 21 | 7.63 | <0.000007 |

| R caudate, R cingulate gyrus | 1026 | 20 | 4 | 31 | 9.13 | <0.000001 | |

| R medial frontal gyrus | 945 | 13 | 33 | 35 | 6.04 | <0.00006 | |

| L insula, L claustrum | 837 | −31 | 5 | 17 | 4.94 | <0.0004 | |

| R superior frontal gyrus | 837 | 23 | 45 | 22 | 7.26 | <0.00002 | |

| Least favorite team | B medial frontal gyrus, B superior frontal gyrus, B anterior cingulate | 2025 | 1 | 38 | 39 | −6.98 | <0.00002 |

| R caudate, R cingulate gyrus | 999 | 10 | −16 | 30 | −6.59 | <0.00003 | |

| B medial frontal gyrus | 702 | 0 | −9 | 61 | −4.48 | <0.0008 | |

| Favorite vs least favorite team | R caudate, B cingulate gyrus | 3645 | 22 | −6 | 22 | 7.97 | <0.000004 |

| L caudate, L cingulate gyrus | 1485 | −10 | 6 | 22 | 6.41 | <0.00004 | |

| L superior frontal gyrus | 972 | −7 | 34 | 48 | 4.98 | <0.0004 | |

| R medial frontal gyrus | 837 | 12 | 35 | 36 | 4.79 | <0.0005 | |

| B anterior cingulate | 783 | 4 | 32 | 23 | 4.71 | <0.0006 | |

All Ps are based on two-tailed testing.

B = bilateral; L = left; R = right.

Fig. 3.

Results of the conducted connectivity analyses. Favorite: connectivity during favorite team trials; Least favorite: connectivity during least favorite team trials; Favorite-least favorite: differential connectivity between favorite and least favorite team trials.

The occipital seed cluster displayed, for the favorite team, positive coupling with parts of right and left claustrum, insula and putamen. It further revealed positive connectivity with an area in the dmPFC. No functional connections with the occipital seed were observed for the least favorite team trials. The favorite vs least favorite PPI demonstrated differential connectivity for two clusters comprising left and right claustrum, insula and putamen, and a cluster in the posterior cingulate cortex. In all cases stronger positive connectivity was observed for the favorite as compared with the least favorite team.

Finally, activity in the dmPFC seed, during the favorite team trials, was positively coupled with activity in left and right caudate and posterior cingulate gyri, in two other areas in the dmPFC, as well as in insula and claustrum. Interestingly, negative coupling with right caudate and cingulate gyrus as well as two areas in the dmPFC were observed for the least favorite team; one of these dmPFC clusters extended into the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The favorite vs least favorite PPI revealed differential connectivity of the dmPFC seed with five clusters, including left and right caudate and cingulate gyri, bilateral ACC and two clusters in the dmPFC.

Between-subjects Spearman correlations

Table 3 displays the between-subjects Spearman correlations between the areas displaying differential activity or connectivities for the favorite vs least favorite team trials, on the one hand, and the difference in behavioral estimates for favorite vs least favorite team trials, on the other hand. Participants who displayed a greater extent of differential connectivities with the occipital cluster were characterized by stronger WT in the behavioral estimates, thus supporting the idea of an attention bias being the central mechanism underlying WT in our study.

Table 3.

Correlations with extent of WT displayed in behavior

| MRI data | Correlation with difference in behavioral estimate (favorite–least favorite) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Spearman's R | P | |

| Differential activation favorite vs least favorite team | ||

| Parietal cluster | 0.50 | =0.08 |

| Occipital cluster | 0.46 | >0.11 |

| dmPFC cluster | −0.02 | >0.95 |

| Differential connectivities between the occipital cluster and | ||

| R putamen, R caudate, R claustrum, R insula, R thalamus | 0.61 | <0.05 |

| L claustrum, L insula, L putamen | 0.66 | <0.05 |

| R posterior cingulate | 0.76 | <0.005 |

| Differential connectivities between the dmPFC cluster and | ||

| R caudate, R cingulate gyrus | 0.22 | >0.47 |

| L caudate, L cingulate gyrus | −0.19 | >0.54 |

| L superior frontal gyrus | 0.54 | =0.06 |

| R medial frontal gyrus | 0.25 | >0.40 |

| R anterior cingulate | −0.19 | >0.53 |

All P's are based on two-tailed testing.

B = bilateral; L = left; R = right; N = 13.

DISCUSSION

Our participants displayed WT and treated their preferred sports team advantageously. In accordance with expectations, we observed systematic differences in participants’ winning estimates for the favorite as compared with the least favorite team. Additional statistical analyses revealed no difference between the neutral and the least favorite team but significantly higher estimates for the favorite than for the neutral team. Thus, the bias observed in our participants’ behavior is largely attributable to a preferential treatment of the favorite team.

On the neural level, we found differential activity between the favorite and the least favorite team in three key areas: The dmPFC, the precuneus/superior parietal lobule and the fusiform gyrus/occipital gyrus. However, activity in none of these areas was per se associated with the degree of WT displayed in our participants’ behavior. Earlier research has related activity in a network comprising the dmPFC and the right precuneus to self-relevance (here defined by social identity), self-reflection and social cognition (Ochsner et al., 2004; Amodio and Frith, 2006). Therefore, activity in these areas may have been related to processes accompanying the WT phenomenon while not being part of the definitive mechanism generating it. For instance, identification with the teams may have created a context of affective preferences without which WT would not have arisen. That we found differential activation in occipital (inferior occipital and fusiform gyri) and parietal areas (superior parietal lobule and precuneus) could further be a sign of selective attention to the information presented (cf Gerlach et al., 1999; Sturm et al., 2006) in the service of these affective preferences (e.g. McDermott et al., 1999).

Limbic (i.e. areas in the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex) and dorsal striatal regions—both structures of the human reward system (Heekeren et al., 2007; Delgado et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2009)—as well as closely related structures typically implicated in emotion processes such as the insula (Craig, 2003; Critchley et al., 2004)—were not per se differentially active for the two teams. However, they were found to be differentially coupled with the occipital and the dmPFC clusters identified to differ between the favorite and the least favorite team trials in the activation analyses. Importantly, only the degree of differential connectivities with the occipital cluster was related to the extent of WT revealed in the participants’ behavior. Therefore, our results are supportive of an attention bias rather than interpretation or response bias being responsible for WT.

Specifically, the occipital cluster differing between the favorite team and the least favorite team was positively coupled with dorsal striatum (putamen and caudate), claustrum and insula during the favorite team trials. Furthermore, the posterior cingulate cortex displayed differential (favorite vs least favorite team) connectivity with this same cluster. Differential connectivity of these areas with the fusiform cortex is in line with the idea that the anticipated reward from seeing the favorite team winning guided the participants’ visual perception and attention in the favorite team trials, and thus supportive of the hypothesis that early selective attention in the service of hedonic needs is an important mechanism in the generation of WT. Interestingly, no coupling of any brain area with the occipital cluster was observed for the least favorite team. This result suggests that the synchronization of activities in the occipital cortex and the reward system we observed for the favorite team was related to positive rather than negative distinction processes in this study (up-regulation of expectancies for the favorite team by the application of selective visual attention).2

Also during favorite team trials, positive coupling of activity in the dorsal striatum (caudate) was observed with activity in the area in the dmPFC that distinguished favorite and least favorite team trials. Conversely, negative coupling between these areas was demonstrated for the least favorite team. Thus, this connectivity pattern is consistent with the idea of a close link between identification and reward processing in our study. That differential activity and differential connectivities for the dmPFC cluster were altogether unrelated to the extent of WT displayed by our participants, on the contrary, is clearly inconsistent with the hypothesis that WT is generated by higher level biased cognitive evidence evaluation or response formation.

Opposed to this latter finding, alternative research on optimism bias suggests higher level cognitive processes to be of particular importance, instead. According to results reported by Sharot et al. (2007), a mechanism of neural activity within limbic and control regions plays a pivotal role. The authors demonstrated reduced activity in the amygdala and the ACC when participants imagined negative future outcomes compared with positive future outcomes as well as positive and negative past outcomes. They suggested that the ACC applies less emotional salience to anticipated negative events (in the sense of an interpretation bias), which then leads to reduced amygdala activity.

The results of Sharot et al. (2007) may appear to diverge importantly from our own data. However, it has to be taken in consideration as well, that, in our experiment in contrast to Sharot's work on optimism, participants faced a favorite and least favorite team. Thus, they did not only anticipate positive and negative events for themselves. In some cases, in our study, negative outcomes may even have been specifically desired (i.e. anticipating low chances for the least favorite team to win the game) and the emotional salience of these outcomes did not need to be reduced. Thus, we would not expect a generally increased activity in the ACC for low vs high chances of winning (irrespective of consideration of team). For the same reason, we would not expect differential ACC activity for the two teams, irrespective of anticipated chances of winning. Moreover, the concrete aims of the study may have been more transparent and consciously perceivable in the Sharot et al. (2007) study than in our own study, thus leading to the implication of higher level cognitive processes.

In sum, our data propose that the occipital cluster and its functional connectivities are specifically involved in the type of WT investigated in our study, whereas activity in the dmPFC—possibly related to social identification—may just ensure the affective context necessary for WT to arise. We outlined that the occipital cluster has been related to visual attention, its functional connections (insula, posterior cingulate, caudate, putamen) to reward processing in earlier research. In our specific case, self-relevance may have activated structures of the human reward system, which in turn synchronized with the occipital cortex to guide visual attention in order to serve individual hedonic needs.

It is important to note, however, that our interpretations concerning the direction of information transmission in the brain during WT are premature since the PPI does not allow for causal inferences. Future research should investigate the flow of information, for instance, whether supposedly attention-related areas are recruited by the limbic and striatal areas, whether the flow of information goes the other way around, or whether influences are bi-directional.

Besides, the neural correlates we identified in our study do not need to be specific to WT. One can very well imagine highly similar neural response patterns in studies that confront individuals with alternative affective-laden situations without any need to take a decision or to make future predictions (e.g. in an affective priming context). Here, selective attention may take place nonetheless and activity in the visual cortex may display similar patterns of connectivities as in the current study.

Finally, our behavioral results demonstrate that WT appears even in tasks with demand for the application of rational Bayesian statistics. Greater effects of WT might be expected when no concrete and explicit objective background information is available, which is the case in most everyday life situations. These real-life situations should give even greater space for the employment of selective attention, for instance, by the activation of memory episodes that serve the goal of a positive identity. In such cases, the reward and regulation systems may be additionally functionally connected to memory-related neural networks.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. P50 MH72850 and the John Templeton Foundation.

Footnotes

1Weinstein (1980) defined this same phenomenon as optimism. We use the term wishful thinking because (i) this is the literature upon which we draw in the present study, (ii) McGuire's concept of wishful thinking predated Weinstein's use of the term optimism to refer to this phenomenon and (iii) contemporary researchers often use the term optimism not to mean Weinstein's definition but to mean the dictionary definition of optimism which implies that individuals display hopefulness and confidence about the future or the successful outcome of something without explicitly referring to individual preferences or affective experiences.

2Remember that, consistent with this observation, our behavioral data did not reveal any systematic difference between the neutral and the least favorite team either and thus suggested a preferential treatment of the favorite team without specific punishment of the least favorite team.

REFERENCES

- Amodio DM, Frith CD. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:268–77. doi: 10.1038/nrn1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babad E. Wishful thinking and objectivity among sports fans. Social Behaviour. 1987;2:231–40. [Google Scholar]

- Babad E, Katz Y. Wishful thinking – against all odds. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1991;21:1921–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cavendini P, Riboldi G, Keller R, D'Annucci A, Bellodi L. Frontal lobe dysfunction in pathological gambling patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:334–41. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. A new view of pain as a homeostatic emotion. Trends in Neuroscience. 2003;26:303–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein T, Öhman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:189–95. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Gillis MM, Phelps EA. Regulating the expectation of reward via cognitive strategies. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11:880–1. doi: 10.1038/nn.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach C, Law I, Gade A, Paulson OB. Perceptual differentiation and category effects in normal object recognition. Brain. 1999;122:2159–70. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DG, Gigerenzer G. Models of ecological rationality: The recognition heuristic. Psychological Review. 2002;109:75–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberg D, Holmberg S, editors. The Political System Matters: Social Psychology and Voting Behavior in Sweden and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Heekeren HR, Wartenburger I, Marschner A, Mell T, Villringer A, Reischies FM. Role of the ventral striatum in reward-based decision making. Neuroreport. 2007;18:951–5. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3281532bd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerschreiter R, Schulz-Hardt S, Mojzisch A, Frey D. Biased information search in homogeneous groups: confidence as a moderator for the effect of anticipated task requirements. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:679–91. doi: 10.1177/0146167207313934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizan Z, Windschitl PD. The influence of outcome desirability on optimism. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:95–121. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott KB, Ojemann JG, Petersen SE, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Akbudak E, et al. Direct comparison of episodic encoding and retrieval of words: an event-related fMRI study. Memory. 1999;7:661–78. doi: 10.1080/096582199387797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ. A syllogistic analysis of cognitive relationships. In: Rosenberg MJ, Hovland CI, McGuire WJ, Abelson RP, Brehm JW, editors. Attitude Organization and Change. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1960. pp. 65–111. [Google Scholar]

- McLean J, Brennan D, Wyper D, Condon B, Hadley D, Cavanagh J. Localization of regions of intense pleasure response evoked by soccer goals. Psychiatry Research – Neuroimaging. 2009;171:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JDE. Rethinking feelings: an fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14:1215–29. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Knierim K, Ludlow DH, Hanelin J, Ramachandran T, Glover G, et al. Reflecting upon feelings: an fMRI study of neural systems supporting the attribution of emotion to self and other. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:1746–72. doi: 10.1162/0898929042947829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, editors. Attitudes and persuasion: classic and contemporary approaches. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Price PC. Wishful thinking in the prediction of competitive outcomes. Thinking and Reasoning. 2000;6:161–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatinelli D, Lang PJ, Keil A, Bradley MM. Emotional perception: correlation of functional MRI and event-related potentials. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:1085–91. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm W, Schmenk B, Fimm B, Specht K, Weis S, Thron A, et al. Spatial attention: more than intrinsic alerting? Experimental Brain Research. 2006;171:16–25. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Flament C, Billig MG, Bundy RF. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1971;1:149–77. [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P, editors. Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain: 3D Proportional System: An Approach to Cerebral Imaging. New York, NY: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Onorato RS. Social identity, personality, and the self concept: a self categorization perspective. In: Tyler TR, Kramer RM, John OP, editors. The Psychology of the Social Self. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 11–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ward BD, editor. Deconvolution Analysis of fMRI Time Series Data (Technical Report) Milwaukee, WI: Biophysics Research Institute, Medical College of Wisconsin; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:806–820. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Proposed revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. Bulletin of Medical Ethics. 1999;147:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue G, Lu ZL, Levin IP, Weller JA, Li XR, Bechara A. Functional dissociations of risk and reward processing in the medial prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:1019–27. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zábojník J. A model of rational bias in self-assessments. Economic Theory. 2004;23:259–82. [Google Scholar]