Abstract

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) represents a subset of AML with t(15;17), responsiveness to ATRA, and a favorable prognosis, yet the impact of FLT3ITD mutations over wild-type (wt)FLT3 remains unclear. We retrospectively analyzed the outcome of 26 APL patients treated at our center according to their FLT3 receptor mutation status. We show that APL patients with an ITD mutation (n = 9) have a lower fibrinogen at presentation (103.5 vs. 235 mg/dl, p = 0.04) and a worse disease free survival (DFS) (p = 0.0114) but similar overall survival (OS) compared to patients with a wt FLT3 (n = 13). Our data suggests that APL with FLT3ITD represents a subset of APL patients who have a higher risk of relapse and should be treated with aggressive therapies upfront, possibly by including targeted therapy in the form of FLT3 inhibitors.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a distinct subtype of acute myeloid leukemia characterized by promyelocytes in the blood and bone marrow, coagulopathy, and characteristic translocation between chromosomes 15q22 and 17q21 [1]. The t(15;17) results in the formation of a fusion protein between the promyelocytic leukemia gene (PML) and retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA). The PML-RARA fusion protein results in a block in myeloid differentiation and is capable of inducing APL in murine models [2,3].

APL patients have been classified into different prognostic categories according to their white blood cell (WBC) and platelet count at presentation [4]. Unlike other AML subtypes where the cytogenetics and the presence of molecular mutations form one of the most important prognostic factors, the value of additional karyotypic abnormalities and/or molecular mutations is unclear in these patients [5,6]. Internal tandem duplication mutations within the Fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor (FLT3ITD) are found in ~30% of patients with AML. Survival data for FLT3ITD-APL is limited to a few studies with small numbers and is conflicting, with some studies showing a worse DFS and OS with others not showing a correlation between the FLT3ITD and prognosis [7–11]. A recent meta-analysis suggests the FLT3ITD is adversely associated with DFS and OS in patients with APL [12].

We analyzed the clinical outcome of patients with APL to determine the relationship between FLT3 receptor status and prognosis.

There were a total of 26 patients with APL for whom FLT3 mutation status was known. There were 13 patients with wt FLT3, 9 with FLT3ITD mutation (1 also had TKD), and the remaining 4 had an isolated TKD mutation. Of the 13 patients with wt FLT3-APL, four had prior chemotherapy and/or radiation (The first patient had received radiation for early stage breast cancer, the second patient received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for breast cancer, the third patient received mitoxantrone for multiple sclerosis, and the forth patient received CHOP chemotherapy regimen for diffuse large B cell lymphoma). No patients in FLT3ITD-APL or FLT3TKD-APL groups had prior chemotherapy or radiation.

Additional cytogenetic abnormalities (ACAs) were seen in 6 patients in the wt FLT3 group (two of these patients had a secondary malignancy), 4 patients in the FLT3ITD group and 2 in the FLT3TKD group. Trisomy 8 was the most common ACA and was found in 3 patients.

Patient characteristics such as age at diagnosis, gender, time to CR, hemoglobin (HgB), platelet count, WBC count at presentation, and coagulation parameters are shown and compared between groups in Table I. One patient in the FLT3ITD and one in the TKD group had microgranular variant APL. Because only a few patients had an isolated FLT3TKD mutation, we restricted our analysis to patients who had either wt FLT3 or FLT3ITD.

TABLE I.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between wt FLT3 and FLT3ITD patients.

| FLT3ITD |

wtFLT3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristic |

N | Median, Range |

N | Median, Range |

P value |

| Age at Diagnosis | 9 | 44(19, 60) | 12 | 41(20, 60) | 0.88 |

| Gender (male/female) | 9 | 5/4 | 13 | 6/7 | 1.0 |

| Time to CR1 (months) | 9 | 1.22 (0.89, 1.74) | 13 | 1.27 (0.92, 2.5) | 0.89 |

| Hgba | 8 | 10.7.(8.6,12.5) | 13 | 10.7 (5.2, 12.3) | 0.49 |

| WBCb | 8 | 16.4 (0.5, 65.7) | 13 | 1.5 (0.5, 7.5) | 0.1 |

| Platelet | 8 | 38.5 (9, 123) | 13 | 42 (8, 204) | 0.64 |

| PTc (sec) | 8 | 17.8 (10.8, 21.4) | 13 | 14.3 (11.2, 21.4) | 0.16 |

| aPTTd (sec) | 8 | 28.3 (22.1, 42.2) | 13 | 27.2 (21.3, 49.9) | 0.29 |

| Fibrinogen | 8 | 103.5 (60, 251) | 12 | 235 (62, 381) | 0.04 |

| ITD Allelic ratio | 9 | 0.2578 (0.04, 0.85) | |||

| ITD length | 9 | 30 (21, 66) | |||

Hemoglobin;

White blood count;

Prothrombin time;

Activated partial thromboplastin time.

The CR rates for patients with wt FLT3 and FLT3ITD were 92 (12/13) and 100% (9/9), respectively. Patients with the FLT3ITD had a lower fibrinogen at presentation than those with wt FLT3 (103.5 vs. 235 mg/dl, P = 0.04). The patients with FLT3ITD appeared to have a higher WBC but it was not statistically significant (P = 0.1). There were no significant differences among the other characteristics described between the two patient groups.

Of the wt FLT3-APL patients, 9/13 were enrolled and treated on CALGB 9710 [13]. Of the remaining 4 patients, two were treated according to the PETHEMA regimen [14], one with a history of breast cancer and significant anthracycline exposure underwent induction with ATRA and AsO3 [15], and the last patient died before therapy could be initiated. Of the 9 patients with FLT3ITD-APL, 5 were treated on CALGB 9710, 2 were treated according to 9710 but off protocol, and 2 with the PETHEMA regimen [13,14].

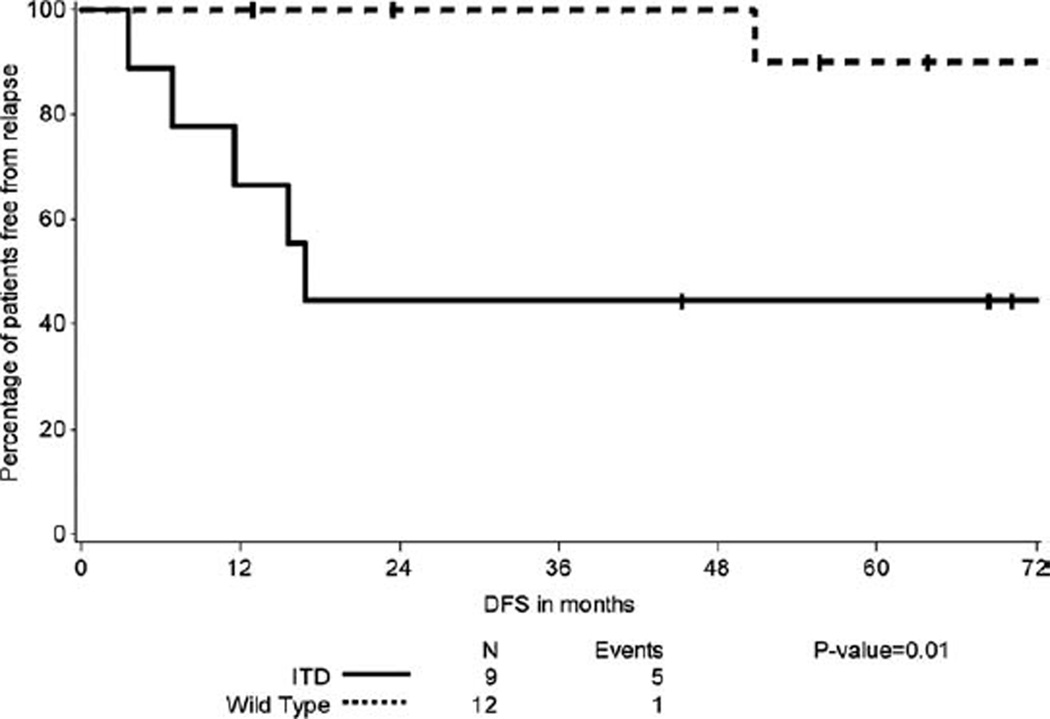

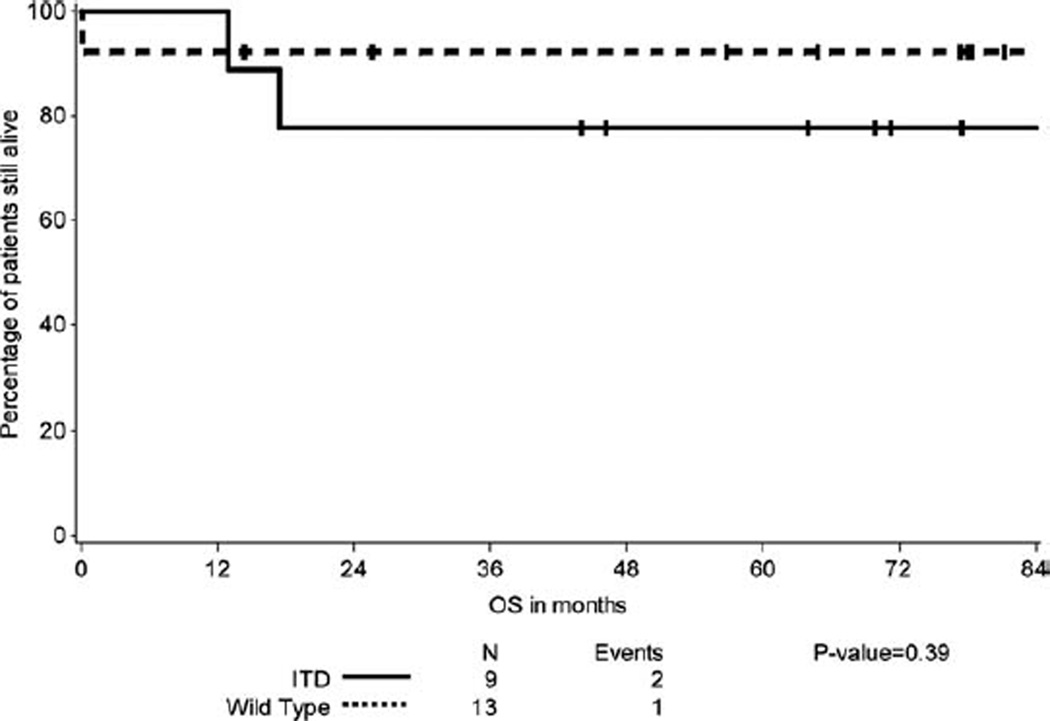

We analyzed the relationship between FLT3 mutational status and DFS and OS. We determined that patients with FLT3ITD-APL have an inferior DFS compared to wt FLT3-APL (Fig. 1) (P = 0.0114). However there was no significant difference in OS between the two groups (Fig. 2) (P = 0.3857). One patient of the 13 with wt FLT3-APL relapsed; this patient was treated with AsO3 reinduction followed by autologous SCT and remains in remission 14 months later. In contrast, 5/9 patients with FLT3ITD relapsed. Of these, 3 received an autologous SCT, one received an allogeneic SCT in CR2, and the fifth patient died within one month of relapse before treatment could be initiated. Two of the 3 patients who received autologous SCT relapsed again and underwent allogeneic SCT in CR3 for one and CR4 for the other.

Figure 1.

Disease free survival of patients with FLT3ITD-APL compared with wt FLT3-APL.

Figure 2.

Overall survival of patients with FLT3ITD-APL compared with wt FLT3-APL.

The ACAs are often observed in APL, although they are not associated with worse prognosis with respect to DFS and OS [4,5,16]. The FLT3ITD mutation is present in 12 to 38% of APL cases [6,9,17], and is associated with the hypogranular variant (M3v) of APL, a short isoform of the PMLRARA (bcr3), elevated WBC, and lower fibrinogen levels [6–8,18].

The exact impact of the FLT3ITD mutation on the prognosis of APL is unclear. In a study of 203 APL patients, FLT3ITD was associated with a higher WBC and a higher incidence of induction-related deaths. However, the remission frequencies, DFS, and OS were similar for ITD and wt patients [7]. Other studies have observed similar CR rates and induction-related deaths regardless of FLT3 mutation status [6,7,17–19]. We observed a similar WBC between ITD and wt patients in our study and the presence of FLT3ITD mutation did not affect CR rates and induction death frequencies in our patient cohort.

Some studies have shown FLT3ITD to be associated with a poor OS in APL patients [6,8,20], however FLT3ITD did not emerge as an independent prognostic factor in multivariable analysis in these studies. A recent metaanalysis by Beitinjaneh et al. showed that FLT3ITD is associated with a poor DFS and OS in patients with APL [12]. Our data confirms the observation that APL patients with a FLT3ITD have a higher relapse risk but differs in that we observe a similar OS given their encouraging outcome following subsequent salvage therapies.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution as our study is limited by small patient numbers, the retrospective nature of our analysis. Notwithstanding these limitations, our data raise the possibility that APL therapy may be improved for patients with FLT3ITD, possibly by incorporating FLT3 inhibitors.

Methods

Patients

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all APL patients who presented to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital between 2002 and 2008 who underwent testing for FLT3 mutations under an IRB-approved protocol. We analyzed outcomes for all adult APL patients who were newly diagnosed and were <60 years of age and had been tested for FLT3 mutations. Patient characteristics, CR rates, DFS, and OS were assessed by medical record review under an IRB-approved protocol.

Mutation analysis

FLT3 mutations, ITD length, sequence and allelic ratio, were determined as previously described [21].

End points and statistics

CR was defined by the presence of a normocellular bone marrow containing less than 5% blasts and showing trilineage maturation with an absolute neutrophil count of more than 1000/ul and a platelet count of more than 100,000/ul [22]. DFS is defined as the duration from the date patient achieved CR to the date of relapse or date of death if death occurred prior to relapse. Patients who did not relapse were censored on the last known alive date. OS is defined as the duration from date of diagnosis to date of death or were censored on the last known date alive if patients were still alive as the time analysis. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate median DFS and OS and log-rank p-values are presented. We assessed the associations of clinical characteristics and the types of mutation patients had using Kruskal-Wallis test. A p-value <0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Harshabad Singh is supported by the Judith Keen Postdoctoral Research Fellowship.

Contract grant sponsor: The Leukemia Discovery and Treatment Fund, Massachusetts General Hospital

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Richard Stone has been a consultant for Novartis.

References

- 1.Wang ZY, Chen Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: From highly fatal to highly curable. Blood. 2008;111:2505–2515. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minucci S, Monestiroli S, Giavara S, et al. PML-RAR induces promyelocytic leukemias with high efficiency following retroviral gene transfer into purified murine hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2002;100:2989–2995. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westervelt P, Lane AA, Pollock JL, et al. High-penetrance mouse model of acute promyelocytic leukemia with very low levels of PML-RARalpha expression. Blood. 2003;102:1857–1865. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanz MA, Lo Coco F, Martin G, et al. Definition of relapse risk and role of nonanthracycline drugs for consolidation in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: a joint study of the PETHEMA and GIMEMA cooperative groups. Blood. 2000;96:1247–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Botton S, Chevret S, Sanz M, et al. Additional chromosomal abnormalities in patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) do not confer poor prognosis: Results of APL 93 trial. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:801–806. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callens C, Chevret S, Cayuela JM, et al. Prognostic implication of FLT3 and Ras gene mutations in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): A retrospective study from the European APL Group. Leukemia. 2005;19:1153–1160. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale RE, Hills R, Pizzey AR, et al. Relationship between FLT3 mutation status, biologic characteristics, and response to targeted therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:3768–3776. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuchenbauer F, Schoch C, Kern W, et al. Impact of FLT3 mutations and promyelocytic leukaemia-breakpoint on clinical characteristics and prognosis in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kainz B, Heintel D, Marculescu R, et al. Variable prognostic value of FLT3 internal tandem duplications in patients with de novo AML and a normal karyotype, t(15;17), t(8;21) or inv(16) Hematol J. 2002;3:283–289. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathews V, Thomas M, Srivastava VM, et al. Impact of FLT3 mutations and secondary cytogenetic changes on the outcome of patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with a single agent arsenic trioxide regimen. Haematologica. 2007;92:994–995. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chillon MC, Fernandez C, Garcia-Sanz R, et al. FLT3-activating mutations are associated with poor prognostic features in AML at diagnosis but they are not an independent prognostic factor. Hematol J. 2004;5:239–246. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beitinjaneh A, Jang S, Roukoz H, Majhail NS. Prognostic significance of FLT3 internal tandem duplication and tyrosine kinase domainmutations in acute promyelocytic leukemia: A systematic review. Leuk Res. 2010;34:831–836. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.01.001. Epub 2010 Jan 21. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell BL, Moser B, Stock W, Gallagher RE, Willman CL, Stone RM, Rowe JM, Coutre S, Feusner JH, Gregory J, Couban S, Appelbaum FR, Tallman MS, Larson RA. Arsenic trioxide improves event-free and over-all survival for adults with acute promyelocytic leukemia: North American Leukemia Intergroup Study C9710. Blood. 2010 Aug 12; doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-269621. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz MA, Martin G, Gonzalez M, et al. Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy: A multicenter study by the PETHEMA group. Blood. 2004;103:1237–1243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estey E, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, et al. Use of all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxide as an alternative to chemotherapy in untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:3469–3473. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez JM, Martin G, Gutierrez NC, et al. Additional cytogenetic changes do not influence the outcome of patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with an ATRA plus anthracyclin based protocol. A report of the Spanish group PETHEMA. Haematologica. 2001;86:807–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo SJ, Park CJ, Jang S, et al. Inferior prognostic outcome in acute promyelocytic leukemia with alterations of FLT3 gene. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1788–1793. doi: 10.1080/10428190600687927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noguera NI, Breccia M, Divona M, et al. Alterations of the FLT3 gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia: Association with diagnostic characteristics and analysis of clinical outcome in patients treated with the Italian AIDA protocol. Leukemia. 2002;16:2185–2189. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shih LY, Kuo MC, Liang DC, et al. Internal tandem duplication and Asp835 mutations of the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2003;98:1206–1216. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Au WY, Fung A, Chim CS, et al. FLT-3 aberrations in acute promyelocytic leukaemia: Clinicopathological associations and prognostic impact. Br J Haematol. 2004;125:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong SA, Mabon ME, Silverman LB, et al. FLT3 mutations in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:3544–3546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4642–4649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]