Abstract

Background

Genomic biorepositories will be important tools to help unravel the effect of common genetic variants on risk for common pediatric diseases. Our objective was to explore how parents would respond to the inclusion of children in an opt-out model biobank.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with parents in hospital-based pediatric clinics. Participants responded to a description of a biorepository already collecting samples from adults. Two coders independently analyzed and coded interviews using framework analysis. Opt-out forms were later piloted in a clinic area. Parental opt-out choices were recorded electronically, with opt-out rates reported here.

Results

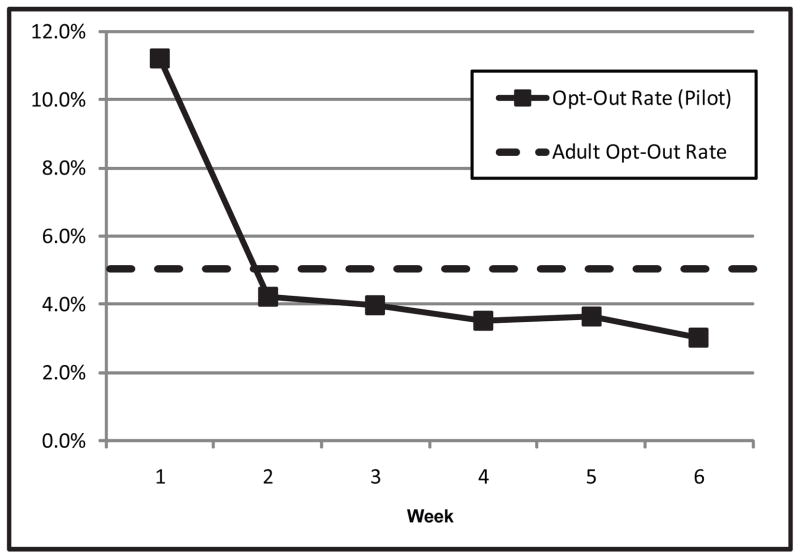

Parents strongly supported medical research in general and expressed a high level of trust that Vanderbilt University would keep their child’s medical information private. Parents were more likely to allow their child’s sample to be included in the biorepository than to allow their child to participate in a hypothetical study that would not help or harm their child, but might help other children. Only a minority were able to volunteer a concern raised by the description of the biobank. The opt-out rate was initially high compared with the opt-out rate in the adult biorepository, but after the first week decreased to near the baseline in adult clinics.

Conclusion

Parents in our study generally support an opt-out model biobank in children. Most would allow their own child’s sample to be included. Institutions seeking to build pediatric biobanks may consider the human non-subjects model as a viable alternative to traditional human-subjects biobanks.

Keywords: pediatric research ethics, biorepository research, genomic research

Introduction

The director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Francis Collins, has predicted a “revolution” of personalized medicine when complete genome sequences become clinically available for all patients in four to five years (Steinbrook 2009). In order for such information to be useful clinically, further work will be required to unravel the effect of common genetic variants on risk for common diseases. While numerous institutional and national-level biobanks have been developed over the past 10 years to elucidate these effects, the creation of population-based biobanks that include samples from children has progressed at a slower pace. This delay is concerning since such biobanks will be necessary to examine the effect of genetic variations in a whole range of conditions that affect children, including such common diseases as asthma, autism spectrum disorder, and prematurity. At least part of the delay in development of pediatric biobanks has been concern that they pose particular ethical and regulatory issues regarding the scope of parental permission and acceptable degree of risk. Many of these issues have been explored in depth in recent publications (Brothers 2011; Hens et al. 2011).

Only three studies to date have reported on parental perspectives on pediatric biobanking initiatives. In 2008, a group at the University of Chicago conducted a survey of post-partum women. This study described a hypothetical pediatric biobank to mothers, and revealed that 48% would enroll their child in a biobank even though 76% agreed that the hypothetical biobank described to them posed minimal risk. Mothers’ assessment of the level of risk entailed by participation in a biobank was not correlated with their willingness to enroll their own children (Neidich et al. 2008). A group in Atlanta reported in 2009 on focus groups they conducted with parents who had participated in a case-control study of birth defects that included optional participation in a biorepository. This study showed that parents of children with birth defects were likely to participate in order to prevent other families from encountering the same problems, while control families were more likely to express an interest in advancing science in general. Parents also reported that they prefer non-invasive methods to collect samples (Jenkins et al. 2009). In 2010, a Belgian group reported on focus groups they had conducted with parents and adolescents to elicit their perspectives on pediatric biobanking initiatives. This study revealed that parental support for nontherapeutic research like biobanks hinges on ensuring that such research pose no burden on the children who participate. This means that only noninvasive means for collecting samples would be supported (Hens et al. 2011). Despite these three studies, there has been no report to date on parental perceptions of a population biobank that is already in operation, although a number of such biobanks are currently collecting samples (Gurwitz et al. 2009). Likewise, there has been no report on parental perception of a biobank that collects only leftover clinical samples.

This study fills those gaps. BioVU is a biorepository that has been in development at Vanderbilt University since 2000. This resource combines de-identified clinical information from electronic medical records of patients with DNA extracted from left-over clinical blood samples. This institutional biorepository qualifies under US human research regulations as non-human subjects research (OHRP 2008). Although research of this type requires neither notification nor permission from participants in order to utilize leftover samples for research, BioVU has adopted a model in which patients are informed of the biorepository through marketing materials. They are then able to opt-out of having their sample included by checking a box on the routine “consent for treatment form” used in all adult outpatient clinics.

We have recently examined the ethical implications that arise in the design and implementation of a biorepository that utilizes this approach. In short, we have argued that patients should be informed of research using leftover blood samples, and should be provided an opportunity to opt out. We find convincing evidence in both empirical research and ethical theory that these efforts are very important; patients deserve respect as humans even if they are not research subjects. Based on this analysis, we have labeled this form of research “human non-subjects research,” a play on the language used in the Common Rule (Brothers 2011; Brothers and Clayton 2010).

After two years of implementation in Vanderbilt’s adult clinics (Pulley et al. 2008; Roden et al. 2008), BioVU was expanded to include pediatric clinics in early 2010. As part of this expansion, we explored parental perceptions of the inclusion of pediatric samples in this pre-existing biobank. We report here on a series of semi-structured interviews that we conducted with the parents of outpatients at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt. The aim of this interview study was to explore parents’ perspectives on collecting leftover blood from children for biobanking. The study was designed to contribute to current knowledge on this topic, but was also intended to meet operational needs to assess how parents might respond to an expansion of BioVU. We supplement the data from these interviews with opt-out data obtained during a pilot period in one of the pediatric clinics. We report this data to provide a quantitative context to our qualitative data. Data was collected during the pilot phase to assess parent responses to the opt-out form, and to help identify and resolve operational challenges.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study based on semi-structured interviews with parents and guardians of pediatric patients. This study was determined to be an exempt study by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board (IRB). Consent for participation was therefore obtained verbally and no personally identifiable information was collected about participants.

Sample

Interviews were conducted with parents and guardians whose children were being seen in either a hospital-based pediatric primary care clinic or a hospital-based multi-specialty pediatric clinic area between December 2008 and March 2009. Subspecialty patients whose parents were interviewed included those being seen by pediatric hematology, genetics, nephrology, and endocrinology providers.

Parents were not asked to identify their race and ethnicity, but electronic “whiteboards” used to manage clinic flow indicate patients’ language preference and last name. We used this information to purposively sample participants from as wide a range of racial and ethnic groups as possible. Both English and Spanish-speaking parents were interviewed; interviews were conducted in Spanish only on days when the Spanish-speaking interviewer was available. Participants who did not speak Spanish but spoke English as a second language were interviewed in English. One of the interviewers had previously practiced medicine at one of the clinic sites, but identified himself only as a researcher to families he had not met before. Families who had previously met him as a provider were excluded.

Parents were approached when clinic staff anticipated that the family would be waiting in the exam room at least 15 minutes before they would be seen by their provider. If more than one adult was present in the exam room, all adults present were invited to participate. Interviews were discontinued if the provider became available to see the patient. For this reason, some participants did not respond to all questions.

We conducted interviews until study personnel agreed that new themes were no longer being encountered in interviews.

Interview guide development

The semi-structured interview guide was developed by a team consisting of two pediatricians who work in research ethics. It was refined for clarity and length on the basis of input from an expert in qualitative research.

Data collection

Parents were approached by an interviewer in the exam room while they waited for their provider. The interviewer briefly explained the interview and obtained verbal consent. Completed interviews lasted between 4 minutes and 15 minutes. Participants were remunerated with a $5 gift card to the hospital food court.

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Spanish-language interviews were transcribed into Spanish and translated into English. The audio recordings were available to the translator as a reference.

The interview included three sections. General perspectives about medical research were elicited. Parents were then provided with a verbal description of BioVU. In order to represent what participants were told, the full transcribed text of the description provided to one participant is provided in Figure 1. This text has been edited to remove such utterances as “okay” and “you know.” On the basis of this description, participants were asked to respond to open-ended questions about the biobank. At the end of the interview, they were asked demographic and other structured questions.

Figure 1.

Sample Transcription of Interviewer’s Description of BioVU

Data Analysis

The structured portion of each interview, including demographics and summative questions, were recorded and analyzed quantitatively. Because we did not attempt to gather a quantitatively representative sample, we have not reported confidence intervals or other statistics appropriate to such samples.

Each interview included open-ended questions aimed at eliciting parental perceptions and opinions. This portion of the study was somewhat focused and informed by previous literature on adult biorepositories. We chose to use a Framework Analysis to examine these data, since this technique is well suited to studies utilizing previously-identified themes (Pope and Mays 2006). Our coding framework was based initially on the domains and themes used in developing the interview guide. Emergent themes were placed within each domain (Figure 2). Two investigators coded every transcript independently and met to refine and update the framework through an iterative process. All coding disagreements were resolved through discussion and transcript review. In a few cases, audio recordings were reviewed to clarify meaning. Coding was performed using an internally-designed spreadsheet on Microsoft Excel software. Using this spreadsheet, we were able to calculate numbers of unique participants who mentioned each theme. We also documented and tallied for each theme whether the participant mentioned the theme spontaneously or the theme was proposed by the interviewer in the course of discussion. Once coding was complete, themes were analyzed for variations within themes and associations of themes with clinical location (primary care clinic versus nsubspecialty clinic).

Figure 2.

Coding Framework

Although parents were invited to express their opinions on a number of issues, many were unfamiliar with the concept of a biorepository. They therefore often required prompting on what concerns they might want to discuss. Responses to these direct inquiries are reported in semi-quantitative terms, since they do not represent themes introduced by participants.

Opt-Out Data

During a ten-week trial period starting in October 2009, one clinic area conducted a pilot of opt-out procedures. During this period, registration staff began distributing opt-out forms to parents checking in to the clinic. Forms were collected and responses were recorded in the electronic medical record. Leftover blood samples were not collected. We report here the weekly opt-out rate during the first six weeks of this trial period. The opt-out rate is calculated using composite data from the electronic medical record. In March 2010, all pediatric clinics began using opt-out forms and storage of leftover pediatric blood samples began.

Results

We conducted 65 interviews. In 16 of the interviews, more than one adult had accompanied the child to the clinic visit. In these cases, the adults who were present were willing to participate, so responses of all these adults were analyzed. In some families all members participated equally in the discussion. In other families, one family member gave longer or more detailed answers than other participants in the room. In one case, the patient was an 18 year old who was continuing to obtain care for his chronic disease from a pediatric provider and was accompanied by his mother. Both were included as participants in this study. Fewer than 5 parents declined to participate. In all, 84 adults participated in the study (Table 1). Reported percentages exclude participants who did not provide a response to the related question. Six interviews were discontinued early when the provider became available to see the patient.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Participant Gender | |

| Female | 67(80) |

| Male | 17(20) |

| Relationship to Patient | |

| Mother | 57(68) |

| Father | 15(18) |

| Grandmother | 10(12) |

| Grandfather | 1 (1) |

| Patient | 1 (1) |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 33(39) |

| 30–39 | 19(23) |

| 40–99 | 16(19) |

| 50 and older | 9(11) |

| No Report | 7 (8) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicaid/SCHIP | 54(64) |

| Other Insurance | 22(26) |

| No Insurance | 0 (0) |

| No Report | 8(10) |

| Recruitment Site | |

| Primary Care Clinic | 48(57) |

| Subspecialty Clinics | 36(43) |

| Language Used in Interview | |

| English | 67(80) |

| Spanish | 17(20) |

Demographics, including age group and the child’s insurance status, are presented in Table 1. The primary care clinic where interviews were conducted provides care primarily to families from underserved populations; no less than half of the families who seek care there self-identify as African-American. This clinic also cares for a number of immigrant families. Fourteen interviews at this site were conducted in Spanish. An additional three interviews were conducted with parents whose first language was neither Spanish nor English, but who spoke English well enough to participate.

Structured Responses

Parents strongly supported medical research in general (98.8%). They were more cautious in their support of research in children (86.1%). Only 9.5% of parents reported that they had participated in medical research in the past, and 15.9% reported that their child had previously participated in research (Table 2). Children being seen in subspecialty clinics were twice as likely to have participated in research in the past, and nearly ten times as likely to recall discussing genetics with a healthcare provider.

Table 2.

Perspectives and Experience with Research

| Response | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Supports Medical Research in General | |

| Yes | 83 (99) |

| No | 1 (1) |

| Supports Medical Research in Children | |

| Yes | 68 (86) |

| No | 7 (9) |

| Maybe | 4 (5) |

| Has Participated in Medical Research | |

| Yes | 7 (10) |

| No | 66 (90) |

| Child Has Participated in Medical Research | |

| Yes | 11 (16) |

| No | 58 (84) |

| Has Given Blood or Body Tissue for Research | |

| Yes | 8 (11) |

| No | 62 (89) |

| Recalls Discussing Genetics with Medical Provider | |

| Yes | 16 (23) |

| No | 55 (77) |

| Vanderbilt Does a Good Job of Keeping Parent’s Medical Record Private | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 69 (100) |

| Neutral, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree | 0 (0) |

| Vanderbilt Does a Good Job of Keeping Child’s Medical Record Private | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 67 (100) |

| Neutral, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree | 0 (0) |

All parents who were asked agreed or strongly agreed that Vanderbilt does a good job of keeping their medical information private. All participants also agreed that Vanderbilt does a good job of keeping their child’s medical information private (Table 2).

Parents were asked whether they would allow their child to participate in a hypothetical study that would not help or harm their child, but might help other children. 83.6% reported that they would allow their child to participate in such a minimal risk study. After Vanderbilt’s biorepository had been described, 88.6% reported that they would allow their child’s information to be included. In comparison, 90.8% of parents reported that they would allow their own sample to be included. One mother who reported that she would allow her own leftover blood to be used for the biorepository was more cautious about the unforeseen consequences of her child’s sample being included:

That is kind of iffy with me. It’s my kids - You do everything to protect your kids. You don’t want anything coming back to bite your kids. So, I can make a conscious decision, on myself, but it would be a lot to think about with my kids.

Parents of children being seen in subspecialty clinics tended to be more supportive of BioVU. 100% of parents interviewed in the subspecialty clinic area reported that they would allow their child’s sample to be included (Table 3).

Table 3.

Willingness to Participate in Research Among Those Who Responded, Primary Care Clinic Patients Compared with Subspecialty Clinic Patients

| Response | Primary Care Clinic N (%) |

Subspecialty Clinic N (%) |

Total N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would allow child to participate in minimal risk research | Total Responses: | 42 | 31 | 73 |

| Yes: | 37 (88) | 24 (77) | 61 (84) | |

| No: | 2 (5) | 5 (16) | 7 (10) | |

| Maybe: | 3 (7) | 2 (7) | 5 (7) | |

|

| ||||

| Would allow child’s sample to be included in BioVU | Total Responses: | 39 | 31 | 70 |

| Yes: | 31 (80) | 31 (100) | 62 (89) | |

| No: | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 4 (6) | |

| Maybe: | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 4 (6) | |

|

| ||||

| Would allow own sample to be included in BioVU | Total Responses: | 42 | 34 | 76 |

| Yes: | 35 (83) | 34 (100) | 69 (91) | |

| No: | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | |

| Maybe: | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | |

Domain 1: Reasons for Supporting Biobank

The reason most consistently mentioned for supporting the BioVU pediatric biobank was its potential benefit to other children. Only one participant mentioned potential benefit to her own child as a reason for supporting the biobank. Three participants whose children were being seen in a subspecialty clinic explicitly supported the biobank because it might yield advances that could help children with the same disease in the future. Many parents were pleased that the biobank would make use of blood that would otherwise be thrown away. This commonly-stated perspective was reflected by a young adult mother, “I feel like [it’s] been drawn, it’s no point in wasting any, though, to help out another child. I’m all for it.”

Domain 2: Concerns Raised about Research

When asked what factors would affect their decision to allow their child to participate in a minimal risk research study, parents most often mentioned the pain or discomfort associated with research. A few who were concerned about pain explicitly mentioned additional blood draws as a procedure that might cause them to choose not to allow their child to participate. One participant stated that she would not allow her child to participate in a minimal-risk research study if it involved needle sticks, “If you’ve got to inject him with something, constantly stick him with pins, no.” Six parents volunteered that their opposition to research in children was based on their view that children should not be used as “guinea pigs”. Others were concerned that research thought to have no risk could lead to unanticipated harms.

Domain 3: Concerns Raised about the Biobank

Approximately 42% of participants were able to volunteer a concern raised by the description of the biobank. Of those who did raise a concern, 8 raised a concern about the privacy of medical record information. In particular, these participants were concerned about stigmatizing medical diagnoses becoming public. One participant denied that she was concerned about the use of medical record information for research, but emphasized the importance of securing that information:

Just long as it’s kept private and it’s not distributed all over the population, because nobody needs to know anything. Just like an AIDS patient… It just needs to stay private.

None raised a reservation about the privacy of genetic information. Four volunteered a concern that they wouldn’t be able to be contacted if research revealed information that might be useful to their child’s medical care. Two expressed a fear about cloning.

In order to stimulate discussion when participants were unable to generate concerns on their own, interviewers sometimes prompted them with risks they might want to consider, such as concerns about privacy of medical information, privacy of genetic information, and inability to recontact parents to provide them with research results. In each case, less than one third of the participants were worried about the proposed risk (Table 4).

Table 4.

Responses to Prompted Concerns

| Concern Raised by Interviewer | Total Responses | Endorsed Concern | Denied Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Privacy of Medical Record Information | 18 | 4 (22) | 14 (78) |

| Privacy of Genetic Information | 22 | 7 (32) | 15 (68) |

| Patient Cannot be Given Research Results | 12 | 3 (25) | 9 (75) |

Domain 4: Opt-Out Form

Parents were given the opportunity to comment on the form already used in adult clinics to present patients with the opportunity to opt-out of the DNA biobank (Figure 3). Most participants stated that the opt-out checkbox was visible on the two page form and that they would notice the checkbox if presented with the form when checking their child into clinic. Several participants suggested improvements to the visibility of the opt-out checkbox or changes in the information provided in the form. There was no consensus about which changes should be made, and in some cases the suggestions made by participants contradicted the suggestions made by others. Only one respondent volunteered that he preferred an opt-in as opposed to an opt-out. Eight participants said they would request more information since they felt the form did not contain enough information for them to understand what they were being asked.

Figure 3.

Opt-Out Section of Consent for Treatment Form

Opt-Out Rates

During the first week of the pilot period, the opt-out rate was high compared with the long-term opt-out rate in the adult biorepository. During the following weeks of the pilot, however, the opt-out rate decreased to near the baseline set in adult clinics (Figure 3). During the first six weeks of the pilot period, 3,834 total consent to treatment forms were signed. Parents checked the “opt-out box” on 212 of those forms (5.5%).

Discussion

Semi-Structured Interviews

The “human non-subjects” biobank at Vanderbilt is the first of its kind. Research conducted during the planning phase indicated that this model was acceptable to patients but that support depended on the availability of an opportunity to opt-out (Pulley et al. 2008). After 4 years, more than 120,000 adult samples have been collected. Agreement to participate remains high, as indicated by the long-term opt-out rate of approximately 5%.

In this study, parents viewed research on children with more caution than research on adults. Some felt that children should not be exposed to research that could harm them physically. A requirement for additional needle sticks was sufficient for some to choose not to allow their child to participate in research. This finding replicates the findings of previous studies that indicate support for pediatrics biobanks depends on the use of noninvasive methods for collecting genetic samples (Hens et al. 2011; Jenkins et al. 2009).

Parents generally report that privacy is only a minor concern for them. This finding is likely due to participant’s high level of trust in the children’s hospital to protect their child’s privacy. This interpretation is supported by a strong correlation between trust in the institution and approval of the biobank observed in a recent survey we conducted (Brothers, Morrison, and Clayton 2011). While all parents in the hospital’s catchment area may not share this same level of trust, this sample, which was collected in a range of hospital outpatient clinic settings, may broadly represent the range of opinions found in those who choose to bring their children to Vanderbilt for outpatient care.

The opt-out model was viewed favorably by nearly all parents. This support seemed to be due to a general acceptance that research is necessary to improve treatments for children and the fact that invasive procedures are not involved. Parents did not seem focused on the benefit this research could provide to their own children. This study did not, therefore, replicate the finding of a previous study that indicated parents sometimes support a hypothetical pediatric biobank based on the misconception that participation might provide direct benefit to their child (Neidich et al. 2008). In this study, the biobank was explained in some detail to participants (Figure 1). In describing the biobank the interviewers made it clear that the biobank contained only deidentified samples. Parents may therefore have been able to deduce that allowing their child’s sample to be included could not lead to a direct benefit for their child.

Despite their concerns, about 90% of parents were willing to allow their own sample and a sample from their child to be included in BioVU and were more likely to allow their child’s sample to be included in BioVU than to allow their child to participate in a minimal risk study. This difference appeared to be due to perceptions of harms entailed by medical research. Parents seemed to assume that medical research, even research described as posing no risk, would involve invasive procedures or the administration of experimental medications. After the biorepository was described to parents, they recognized that neither of these risks were relevant to BioVU. Several parents expressed concern about the discomfort that derived from additional needle sticks and therefore seemed enthusiastic about an approach to research that uses only leftover blood. Only one parent said she would allow her sample to be included but not her child’s.

Administrative leaders responsible for the biorepository were provided initial results from the study reported here. This information informed the decision to expand the biorepository to include samples from the children’s hospital and clinics. Parent responses were also factored into the design of the pediatric consent for treatment form, which adopted the same check-box format and notification language used in the adult iteration of the biorepository.

Pilot Opt-Out Rates

The initial high opt-out rate during the pilot appears to be attributable to an operational barrier. The front desk staff reported that although Spanish-speaking interpreters were available in person to assist with the check-in process, phone interpreters were used for other non-English languages. The phone interpreters encountered difficulty interpreting the opt-out form. In the view of the staff, therefore, many limited English proficiency families chose to opt-out since the confusion could not be resolved. This communication issue was quickly resolved, and the opt-out rate decreased to near the rate observed in the adult clinics.

Limitations

This study had four significant limitations. First, the sample was collected in a variety of settings in order to get the largest possible range of perspectives. The quantified findings may therefore not represent the true frequencies in the target population, but may well represent the range of perspectives found among parents who bring their children for outpatient care at this institution.

Second, 16 of the 65 interviews included more than one family member. Family members may therefore have influenced the responses of each other. 21% of direct questions were answered by only one family member. When more than one family member provided a response, they agreed with one another 95% of the time. We cannot know whether this strong pattern of agreement was due to shared background and experiences or due to bias introduced during the interviews, but the concordance of these responses had little impact on our overall findings, which were quite consistent overall.

Third, open-ended questions generated only brief responses. This could be due to limited knowledge on the part of the participant about the ethical concerns that have been raised with respect to biorepositories. We did not formally assess participants’ understanding of the description they were provided of the biorepository, although many made comments that made it clear that they understood the structure and aims of the biorepository in general terms.

Fourth, the strong level of support for this biorepository model may not be generalizable since this support appears to be strongly linked to trust in the institution. However, this connection between trust and support for an opt-out model is an important finding that can inform feasibility studies at other institutions seeking to reproduce this model. This finding has also been replicated in quantitative work related to the same biorepository (Brothers, Morrison, and Clayton 2011).

Conclusion

Parents in our study generally support an opt-out model biobank in children. Most would allow their own child’s sample to be included, as shown both in their responses to interviews and by their decisions not to opt out during the pilot. Even though they identified a difference between research in adults and children, they did not draw strong distinctions between the inclusion of samples from adults and samples from children in this biobank. Institutions seeking to build pediatric biobanks may want to consider the human non-subjects model as a viable alternative to traditional human-subjects biobanks. This model is particularly well-suited for pediatrics where support, and therefore participation, may depend on minimizing invasive testing. Institutions seeking to develop biobanks following the human non-subjects model should evaluate the level of trust parents have that the institution will utilize samples responsibly, since this is a key element in overall support for this model.

Figure 4.

Opt-Out Rate Trend During Pediatric Trial Period

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff and physicians at the Vanderbilt Pediatric Primary Care Clinic and the Doctor’s Office Tower Sixth Floor Clinic Area, as well as their patients, for assisting with this study. We would also like to thank Jill Fisher and Dan Morrison who provided advice on the design of this study and the analysis of data, and Jill Pulley, Melissa Basford, Janey Wang, Erica Bowton, Denise Lillard, and Erika Digby who assisted with this study. This study was funded by the Vanderbilt Genome-Electronic Records Project, NIH/NHGRI grant 5U01HG004603-03, and the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR), NCRR/NIH grant UL1 RR024975. Dr. Brothers had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Kyle B. Brothers, Vanderbilt University

Ellen Wright Clayton, Vanderbilt University.

References

- Brothers KB. Biobanking in pediatrics: the human nonsubjects approach. Personalized Medicine. 2011;8(1):71–79. doi: 10.2217/pme.10.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers KB, Clayton EW. ‘Human Non-Subjects Research’: Privacy and Compliance. American Journal of Bioethics. 2010;10(9):15–17. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2010.492891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers KB, Morrison DR, Clayton EW. Two Large-Scale Surveys on Community Attitudes Toward an Opt-Out Biobank. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34304. (Epub ahead of print, Nov. 7, 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitz D, Fortier I, Lunshof JE, Knoppers BM. Children and population biobanks. Science. 2009;325(5942):818. doi: 10.1126/science.1173284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hens K, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. Risks, Benefits, Solidarity: A Framework for the Participation of Children in Genetic Biobank Research. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;158(5):842–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hens K, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. The Storage and Use of Biological Tissue Samples from Minors for Research: A Focus Group Study. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14(2):68–76. doi: 10.1159/000294185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins MM, Reed-Gross E, Rasmussen SA, Barfield WD, Prue CE, Gallagher ML, Honein MA. Maternal attitudes toward DNA collection for gene environment studies: A qualitative research study. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2009;149A(11):2378–2386. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidich AB, Joseph JW, Ober C, Ross LF. Empirical data about women’s attitudes towards a hypothetical pediatric biobank. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146(3):297–304. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHRP. Guidance on Research Involving Coded Private Information or Biological Specimens. Rockville, MD: Office of Human Research Protections; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative Research in Health Care. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing/BMJ Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pulley JM, Brace MM, Bernard GR, Masys DR. Attitudes and perceptions of patients towards methods of establishing a DNA biobank. Cell and Tissue Banking. 2008;9(1):55–65. doi: 10.1007/s10561-007-9051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden DM, Pulley JM, Basford MA, Bernard GR, Clayton EW, Balser JR, Masys DR. Development of a Large-Scale De-Identified DNA Biobank to Enable Personalized Medicine. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;84(3):362–369. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrook R. Opportunities and Challenges for the NIH -- An Interview with Francis Collins. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(14):1321–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0905046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]