Abstract

The application use of organometallic compounds into the cancer research was established in the late 1970s by Köpf-Maeir and Köpf. This new research area has been developed for the past thirty years. In the early 1980s, Jaouen and coworkers recognized the potential application of organometallic compounds vectorized with pendant groups that can deliver the drug to certain specific receptors. This is what is called nowdays Target Specific Drugs. This review will focus on metallocenes vectorized with steroids derivatives of hormones, nonsteroidal and selective endrocrine modulator.

Keywords: metallocene, anti-proliferative, cytotoxic, selective endrocine modulator, hormones, cancer

1. Introduction

The first report on the anti-tumor properties of titanocene dichloride (I), Cp2TiCl2, in 1979 by Köpf-Maier and Köpf, revolutionized the idea regarding metal-based drugs and the previous concept that organometallic complexes, under aqueous and physiological media and their application to biology and medicine were incompatible [1]. This report opened a new exciting area of research: BioOrganometallic Chemistry. In the early 1980’s, Köpf-Maier and Köpf continued investigating the biological activity of other metallocenes and found that many metallocenes such as Cp2MX2 (M = Ti, V, Nb, Mo; X = halides and pseudo-halides), Cp2Fe+ and main group (C5R5)2M (M = Sn, Ge; R = H, CH3) exhibited anti-tumor activity against a wide variety of tumor cells (among them Ehrlich ascites tumor, B16 melanoma, colon 38 carcinoma, Lewis lung carcinoma) with less toxic effects than the well reputed cis-platin [2–7]. Cp2TiCl2 was the most active species in colon, breast and lung cancers reaching phase I and II clinical trials [8–12] but its low response in metastatic cancers discourage its further investigation and the clinical trials were abandoned.

In the subsequent years, different strategies were pursued by several research groups to modify structure and improve anti-tumor activity from replacing X ancillary ligands with hydrophilic one to functionalization of the Cp ring with hydrophobic or hydrophilic groups and bioactive molecules. The last strategy has been very attractive to tailor organometallic complexes with predetermined properties. Perhaps the most exciting among these strategies is the functionalization of the Cp ring with pendant groups to develop target specific drugs. In particular, pendant groups that can be recognized by a receptor and function as an antagonist to certain types of hormone dependent cancers have attracted the attention of various investigators. Currently, there are several organic compounds as selective receptor modulators (SRM) to cancers with high receptor expression, in particular to hormone dependent such as breast, ovarian and prostate cancers [13–18]. In a similar manner, metal-based drugs that either behaves as SRM or antagonist to these receptors can be developed and it is the subject of this review.

2. Target Specific Drugs for Breast and Prostate Cancers

2.1 Precedents: An Overwiew

The idea of target specific drugs relies heavily on the fact that certain cancers, in the initial stages, express higher amount of hormone receptor. The principle is to synthesize a species that can be recognized by the receptor and behaves as an antagonist, impairing the receptor function. Certain structural scaffolds and properties are needed to obtain this property. The most important one are the organic moiety that can be recognized by the receptor and the organometallic group that can express its cytotoxic activity and impair the protein function.

The idea of incorporating an organometallic functionality to a hormone was originally explored in the early 1980’s by Jaouen and coworkers and the precedents discussed in this Overview section belongs exclusively to G. Jaouen research. We discuss in this review what we consider the most important research results. [19,20]. Briefly, the functionalization of protected estradiol, (3-O-R-l7β-O-R′-estradiol) by Cr(CO)3 lead to the formation of α- and β-(3-O-R- l7β-O-R-estradiol)tricarbonylchromium diastereoisomers, (R = H, tBuMe2Si, HO(CH2)3 and R′ = H, Bz, tBuMe2Si) depending on which face of the steroid the Cr(CO)3 is bound, Figure 1. The initial goal of this series of organometallic-labeled hormones was to develop biochemical markers, in particular to detect the amount of estrogen receptor in breast tissues. In the early stages, breast cancer expresses higher amount of estrogen receptor (ER). Since, some these complexes presented high estrogen receptor binding affinity (RBA), these species can be used as diagnostic assay for breast cancer. However, RBA depends on which face (α and β) the tricarbonylchromium group is coordinated. It was determined that the α diastereoisomer has much higher RBA than the β [20]. Along these lines, α-(3-O-(CH2)3OH-l7β-OH-estradiol)tricarbonylchromium has a high RBA of 28 (RBA of estradiol is 100-used as a control) and it was the first complex tested for estrogen receptor determination using FT-IR spectroscopy in the carbonyl region [20].

Figure 1.

α- and β-(3-O-R-l7β-O-R′-estradiol)Cr(CO)3 diasteroisomers.

Subsequently, other organometallic-labeled estradiol derivatives were synthesized where Cr(C0)3, Cp*Ru+, or Cp*Rh2+ fragments are either bound to the 17α-position or in the α and β face of the A-ring of the 17β-estradiol, Figure 2 [21,22]. The receptor binding affinity (RBA) of these organometallic-labeled estradiol where determined and it was found that the cationic species, as well as the β-face diastereoisomer of the A-ring, have very low and in some cases no binding affinity to the ER. This brief introduction clearly showed that the organometallic-labeled estradiols were synthesized mainly as biochemical markers, in particular the tricarbonylchromium-estradiol derivatives in which the stretching modes of the terminal carbonyl groups (ν(CO)symm) of the chromium-carbonyl can be detected by Infrared Spectroscopy in a region where the protein has no absorption.

Figure 2.

Structures of organometallic-labeled estradiol at the A-ring (left) and 17α-position of the 17β-estradiol.

Other organometallic-labeled hormones species at the 17-α position where prepared as possible biomarkers in immunoassays [23,24]. For instance, 17α-ferrocenyl-17β-estradiol (Figure 3) was synthesized as a biomarker for immunoassay as it has good RBA for the ER. Synthetic methodology also has been developed to attach Mo2Cp2(CO)4, Co2(CO)6 and M3(CO)10 (M = Ru, Os) groups in hormones as possible carbonylmetalloimmunoassay using FT-IR as a method of detection [23,24]. Their RBA for ERα were determined and grouped in three classes according to their ER inactivation: a. strong (Co, Fe), b. moderate (Os and Ru) and c. weak (Mo). Particularly important, 17α-ferrocenyl derivative has high receptor inhibition, combined with the fact that ferrocenium has cytotoxic activity clearly demonstrated the potential use of functionalized hormone with organometallic groups in cancer therapy and imaging agents.

Figure 3.

Structures of 17α-organometallic labeled 17β-estradiol.

Recognizing the potential use of these organometallic-labeled hormones as imaging agents or radiotherapy, due to their RBA to ER, a series of rhenium and manganese carbonyl complexes of β-estradiol were synthesized and their RBA were determined, Figure 4 [25]. Rhenium has two radioactive isotopes, 186Re and 188Re which make these appropriate to be used as radiopharmaceuticals.

Figure 4.

Structure of 17α-[(R-C5H4)M(CO)3]-17β-estradiol. M = Mn, Re; R = CH2, C2.

Receptor binding affinity of these species showed a correlation between the complex affinity to ERα and the spacer linking the organometallic group to the hormone at C(17). The organometallic-labeled hormones containing CH2 group as linker, are flexible and the free rotation around the C(17)-CH2 and CH2-(C5H4) bonds generates conformations with high steric demands, with organometallic fragment positioned away from the D ring and limiting the access of these species into the ligand binding pocket (LBP). Therefore, they exhibited low RBA values (2.5 for CH2-CpMn(CO)3 and 0.8 for CH2-CpRe(CO)3). In contrast, the ethynyl linker positions the organometallic group underneath the steroidal C and D rings. This compact conformation can fit better in the LBP of the ER and as a consequence of this, the compounds containing the ethynyl linker showed high RBA values (15–29). This hypothesis was supported by Molecular Modeling studies [25].

2.2 Functionalized Ferrocene as Endrocrine Modulator and their Anti-cancer Activity

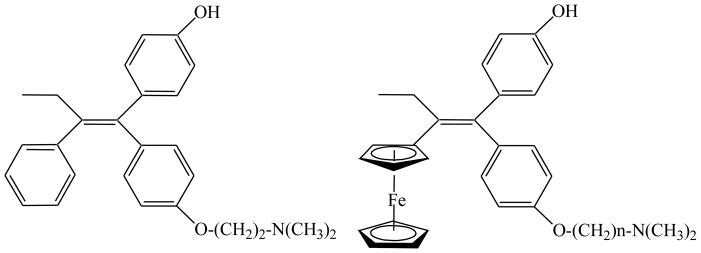

The research results presented above provided the ground to develop functionalized ferrocene with endrochrine modulators. In 1996, Jaouen and collaborators reported the first ferrocene coupled with the active metabolite of tamoxifen, hydroxytamoxifen, HO-TAM, Figure 5 [26,27]. These species combine the anti-estrogenic effect of tamoxifen and the cytotoxic properties of ferrocene. In principle, the new compounds should exhibit high recognition by the estrogen receptor due to the presence of the tamoxifen group and anti-proliferative activity of ferrocene as a result of producing ferrocenium cation, Fc+, and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) inside the cell. Thus, the tamoxifen is the vector (shuttle) of ferrocene to introduce it inside the cell.

Figure 5.

Hydroxytamoxifen (left) and hydroxyferrocifens (right), n = 2–5, 8.

We will continue to discuss selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) since there are many derivatives synthesized using tamoxifen as a vector. Due to the arsenal of compounds existing in this area, only representative examples will be presented.

The synthetic methodology selected for these ferrocifens and hydroxyferrocifens provides the functionalized ferrocenes in a mixture of Z and E isomers, Figure 6 [26,27]. In some cases, the Z and E isomers can be separated by HPLC, fractional crystallization or plate chromatography.

Figure 6.

Ferrocifen structure in the Z and E configurations.

The X-ray structures of Z-1-[4-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)phenyl]-1(phenyl-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene), ferrocifen, and E-[4-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)phenyl]-1(4-hydroxyphenyl-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene) are depicted in Figure 7 [26,28]. In comparison with the cis- and trans-tamoxifen, both ferrocifens (Z and E) showed a slight lengthening of the central C=C (but-1-ene) bonds, 1.34 Å (Z) and 1.33 Å (E) for the former versus 1.37 Å (Z) and 1.36 Å (E) for the ferrocifens. The bonds angles between the C=C bond and the substituents also changes, in particular the angle at the side where the ferrocenyl group is located. These angles are widened as compared to tamoxifen, as a consequence of greater bulkiness of the ferrocene versus the phenyl group [26,28].

Figure 7.

Ortep diagrams of Z-1-[4-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)phenyl]-1(phenyl-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene), ferrocifen (top), and E-[4-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)phenyl]-1(4-hydroxyphenyl-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene), bottom. (Z)-4a and (E)-3a numbering adopted by reference and not related to numbering in Table 1. Reproduced with permission of J. Organometallic Chemistry.

In general, the Z isomer showed higher RBA to ERα and ERβ than the E isomer. However, in solution the Z undergoes isomerization leading to a mixture of 50:50 (Z:E). Hence, the anti-proliferative effects of many of the ferrocifens are determined in a mixture of isomers, unless specified, in hormone-dependent MCF-7 and hormone-independent MDA-MB-231breast cancer cell lines. Also the RBA to the two isoforms of ER, ERα and ERβ, was also determined. The biological data of selected ferrocifens are recorded in Table 1 [29].

Table 1.

Relative binding affinity of the compounds on the two estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and cell viability and IC50 on hormone-dependent MCF-7 and hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines at 5 days. Data from references 28–34.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | RBA | Cell viability at 1μM (%) or IC50 | ||

| ERα | ERβ | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | ||

| 1. p-OH | O(CH2)2N(CH3)2 | 14.6 | 10 | 29 % | 48 % |

| 2. p-OH | O(CH2)3N(CH3)2 | 11.5 | 12 | 14 % | 0.5 μM |

| 3. p-OH | O(CH2)4N(CH3)2 | 12 | - | 37 % | - |

| 4. p-OH | O(CH2)5N(CH3)2 | 5 | 6 | 19 % | 20 % |

| 5. p-OH | O(CH2)8N(CH3)2 | 2.3 | - | 47 % | 85 % |

| 6. p-OH | H | 4.6 | 11 | 79 % | 1.13 μM |

| 7. p-OH | OH | 9.6 | 16.3 | 34 % | 0.44 μM |

| 8. m-OH | H | 3.6 | 0.53 | 158 % | 2.7 μM |

| 9. m-OH | OH | 5.4 | 2.4 | 105 % | 1.03 μM |

| 10. p-Cl | H | 0.24 | 0.36 | 152 % | 83 % |

| 11. p-Br | H | 0.26 | 0.55 | 153 % | 86 % |

| 12. p-CN | H | 0.41 | 0.31 | 133 % | 11 μM |

| 13. p-NH2 | H | 2.8 | 1.08 | 180 % | 0.8 μM |

| 14. p-O-CH3 | O-CH3 | 0.2 | 0.26 | 151 % | 101 % |

| 15. HO-TAM | 39 | 24 | ~ 24 % | 100 % | |

| 16. estradiol | 100 | 100 | Proliferative | Proliferative | |

| 22a. | 0.24 | 0.06 | 135 % | 2.8 μM | |

| 22b. | 0.15 | 0.01 | 116 % | 3.5 μM | |

First, all the ferrocifens showed less receptor binding affinity (RBA) to ERα and ERβ receptors than HO-TAM. Remarkably, for hydroxyferrocifens 1–5, as the chain (R2) is lengthened the RBA for ERα decreases [28]. On the hormone-dependent MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, at a concentration of 1 μM, hydroxyferrocifens 1–5 showed similar and in some cases better anti-proliferative effect than HO-TAM. Hydroxyferrocifens 2 (n = 2) and 4 (n = 5) exhibited better anti-proliferative effects than HO-TAM. The other ferrocifens, 6–14, showed lower anti-proliferative activity than HO-TAM.

To understand the possible mechanism of action of ferrocifens in ERα, Molecular Modeling studies of the drug docking of into the receptor were pursued. Molecular Modeling studies on ferrocifens 2 (n = 3, Figure 8) and 3 (n = 4) demonstrated that the molecule can fit into the binding site of the ERα, adopting an antagonist configuration analogous to HO-TAM [28,30]. Possible interactions between His524 and the ferrocenyl group and Asp351 and the nitrogen of the O(CH2)3N(CH3)2 group are key factors that stabilize this docking.

Figure 8.

Interaction of 2 docked in the ERα LBD, only the aminoacids in the binding pocket are shown. 2 is represented as space-filling model. Reproduced with permission of Dalton Transaction.

The subject ferrocenyls were also screened for their anti-proliferative effects on the hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line (Table 1) and showed that many of the ferrocifens, particularly those containing phenolic groups (mostly para-subsitituted) have high anti-proliferative activities [28–34]. Notably, 13 (p-NH2 substituted) showed significant anti-proliferative activity in MDA-MB-231 but no activity in MCF-7 cells. As HO-TAM is completely inactive in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line, the anti-proliferative effect proceeds from the cytotoxic effect of the ferrocene moiety whereas for MCF-7 both, anti-hormonal (anti-estrogenic) and cytotoxic effects, contribute to the anti-proliferative effect. In this regard, the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line does not contain ERα but contains ERβ. ERβ is responsible for the intracellular redox processes and it can also be a target for the ferrocifens. Ferrocenyl group can be easily oxidized to Fc+ radical in presence of water and the ERβ could be involved in this Fc/Fc+ redox process.

Likewise, a series of ruthenocifens and CpRe(CO)3–TAM derivatives (Figure 9) were synthesized and screened in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells and the RBA for ERα and ERβ determined [29,30,35,36]. While these species were recognized by both receptors, they showed moderate anti-proliferative activity on MCF-7 and no anti-proliferative activity on MDA-MB-231, analogous to HO-TAM. This demonstrated their anti-proliferative activity proceeds only from the anti-estrogenic (anti-hormonal) effect on these species and not from the cytotoxic effects of the organometallic moiety.

Figure 9.

Structures of ruthenocifens and CpRe(CO)3–TAM derivatives (left) and titanocifen (right). R1 = OH, R2 = O(CH2)nN(CH3)2 (n = 2, 3, 4, 5, 8) and R1 = OH = R2.

Surprisingly, titanocifen (Figure 9) showed a proliferative effect (estrogenic effect) on MCF-7 breast cancer cell line almost as strong as estradiol. This intriguing result led to investigate the effect of Cp2TiCl2 on MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The estrogenic effect of titanocene dichloride was higher than titanocifen [30].

Sadler and co-workers published a study suggesting that titanocene dichloride under physiological medium undergoes a “stripping process” and Ti(IV) is loaded on the iron binding sites in human transferrin [37,38]. Ti(IV) enters into the cell by transferrin receptor mediated endocytosis. Once Ti(IV) is inside the cell, possible coordination with estrogen receptor was considered [30]. Hence, to explain the titanocifen proliferative (estrogenic) activity on MCF-7, a molecular modeling study on possible coordination of Ti(IV) on the ERα was performed, Figure 10. The study showed that Ti4+ is surrounded by cysteine 381 and glutamic acid 380 of helix 4 and histidine 547 of helix 12. Ti4+ is located on the gap between these two helices and can activate the receptor, in a similar manner as estradiol [30].

Figure 10.

Representation of the interaction of Ti4+ in the ERα LBD. Reproduced with permission of Dalton Transaction.

In light of these results, Jaouen and collaborators pursued an electrochemical study to understand the mechanism underlining these hydroxyferrocifens [32,33,39,40]. This study was designed to assess the role of the ferrocene and the p-phenol groups linked by a π system and the anti-proliferative effects, to develop a structure-activity relationship on these hydroxyferrocifens.

A series of hydroxyferrocifens compounds (Figure 11) were used for the biological screening and electrochemical study aimed to test the hypothesis about the formation of the quinine methide (QM) species as a result of the in vitro oxidation of the phenol via the ferrocene group.

Figure 11.

Hydroxyferrocifens compounds used for the electrochemical study, Fc = ferrocene.

In the hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 cell line, compounds 6, 7, 17 and 22 (Figure 11) as well as hydroxyferrocifens, n = 2, 3, 5 (Figure 5, compounds 1, 2 and 4 in Table 1) have anti-proliferative activity while compounds 18–21 have little or no effect on this cell line, see Table 2. Also diphenol derivative 7 is more cytotoxic than monophenol 6. The cyclic voltammetry study showed that, in MeOH, all compounds have a reversible wave due to Fc/Fc+ redox couple and accompanied, in most of the compounds containing a phenol group, by an irreversible oxidation of the phenol moiety. On the other hand, in presence of a base (pyridine), those compounds that have low or not cytotoxic activity (18–21, 22b) showed no change in their electrochemical behavior whereas the compounds with anti-proliferative effect on MDA-MB-231 cell line, showed an irreversible Fc/Fc+ redox couple with an increase in the Fc oxidation wave, suggesting the Fc+ radical is unstable and further react with other species (scavenged) prior to the reverse sweep. Moreover, for those compounds exhibiting phenol oxidation waves, the presence of pyridine, induced a remarkable cathodic shift on these oxidation waves. Based on these experiments, the authors proposed a possible mechanism to explain the electrochemical and biological screening data, Figure 12.

Table 2.

Relative binding affinity of the compounds on the two estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and percentage of inhibition and cytotoxic effects on MDA-MB-231 cells at 5 days. Data from references 32, 33, 39 and 40.

| Compound | RBA | % inhibition at 1μM | Cytotoxic effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | ERβ | MDA-MB-231 | ||

| 17. | 49% | positive | ||

| 18 | 0.9 | 0.28 | 93% | negative |

| 19a | 2.1 | 7.5 | 26% | slight |

| 19b | 4.6 | 15.5 | 18% | slight |

| 19c | 18.2 | 28 | 16% | slight |

| 20 | 16% | slight | ||

| 21 | 3% | negative | ||

Figure 12.

Proposed mechanism for hydroxyferrocifen conversion to quinine methide.

First, the phenolic group is necessary for the electron transfer to occur, and this intramolecular electron transfer to the ferrocenyl moiety is mediated by a weak electron delocalization with the π system, see Figure 12. It is important to point out that compounds 19a,b,c do not contain a π system to delocalize electrons and compounds 21 and 22b (Figure 13) cannot stabilize the quinine methide(QM) species thus being unable to follow the proposed QM mechanism due to the lack of the beta proton [32,33,39,40].

Figure 13.

Compound 21a showing there is no H at β position available for the proposed QM (above) mechanism.

Other studies were pursued to develop structure-activity relationship of the ferrocifens, see Figure 11 and Table 1 and 2, above. Among the findings are the following. First, the diphenol 7 possesses higher anti-proliferative effect than the monophenol 6 [41]. Second, compounds containing para-phenol (6 and 7) are more cytotoxic than those containing meta-phenol groups, 8 and 9 [35,39]. In general p-phenol group on the ferrocifens imparts more cytotoxic activity than m-phenol. Compounds 22a and 22b showed low cytotoxic effect apparently as a result of the bulkyness (steric hinderance) of Fc group.

The position of the Fc on ferrocifen was also investigated, Chart 1 [42]. Ferrocenyls 23a–23d showed proliferative effect on MCF-7 and their proliferative effects are RBA-dependent and have moderate anti-proliferative effect on androgen receptor–independent PC-3 prostate cancer cell line, see Table 3. Compounds 24, 26, 27 have proliferative effects on MCF-7 but in PC-3 cell line they have very low and in some cases non-existent anti-proliferative activity. Only 25 xhibited anti-proliferative activity on both cell lines. Interestingly, screening of 25 on MCF-7 in presence and absence of estradiol demonstrated that this compound at low concentration (1 nM) has estrogenic properties and at higher concentrations (1 μM or higher) has a combination of estrogenic and cytotoxic effects, being cytotoxicity the dominant property.

Chart 1.

Table 3.

RBA on ERα and ERβ and IC50 values, on hormone-dependent MCF-7 and hormone-independent PC-3 cell lines at 5 days. Data from reference 42.

| Compound | RBA | Cell viability at 1μM (%) or IC50 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | ERβ | MCF-7 | PC-3 | |

| 23a. | 11.9 | 16.4 | 181 % | 12 μM |

| 23b. | 0.9 | 2.8 | 173% | 9.8 μM |

| 23c. | 0.45 | 1.8 | 118 % | 10.2 μM |

| 23d. | 0.24 | 1.26 | 107 % | 12 μM |

| 24a. (Z) | 0.16 | 0.83 | 166 % | 90 % |

| 24b. (E) | 0.13 | 0.18 | 192 % | 84 % |

| 25a. (Z) | 14 | 12 | 54 % | 7.8 μM |

| 25b. (E) | 1.19 | 1.59 | 62 % | 8.3 μM |

| 26 | 4.1 | 6 | 108 % | 83 % |

| 27a. (Z) | 2.3 | 1.6 | 178 % | 102 % |

| 27b. (E) | 4.6 | 6 | 164 % | 96 % |

Finally to finish with SERM, cyclic diphenol ferrocenyl compounds were synthesized and screened for anti-proliferative activity. The study revealed that these cyclic ferrocenyls (28 and 29, Chart 2) on MCF-7 cells are more potent than the hydroxyferrocifens (6 and 7) [43]. However, their anti-proliferative effects are better expressed on MDA-MB231 and PC-3 cell lines. In MDA-MB231 and PC-3 cell lines, 28 showed outstanding anti-proliferative effect with an IC50 value of 0.09 μM. This is the most active ferrocenyl compound reported among the ferrocifen series [43].

Chart 2.

Likewise, Jaouen and coworkers synthesized a series of ferrocenyl-aryl-hydantoin, a nonsteroidal antiandrogen nilutamide derivatives bearing the organometallic group at position N(1) or at C(5) of the hydantoin ring, Chart 3 [44]. Conceptually, the idea of linking an antiandrogen to ferrocenyl is the same as the previous synthesized SERM compounds. The introduction of a cytotoxic organometallic group to an anti-androgenic molecule (nilutamide) could lead to potent therapeutic agents to hormone-dependent and –independent prostate cancers. In principle, the anti-androgenic properties of nilutamide could be preserved and at the same time the intrinsic cytotoxic effect of the organometallic moiety is retained, resulting in novel anti-cancer agents with high anti-proliferative properties.

Chart 3.

The RBA for androgen receptor (AR) was determined and compared to two nonsteroidal antiandogren drugs, nilutamide and bicalutamide, Table 4. All the compounds including nilutamide and bicalutamide showed low RBA for AR. Compounds 1 and 2 have the highest RBA values in the series of compound, comparable to bicalutamide and higher than nilutamide. However, as we have presented for ferrocifens, the RBA values do not always correlate with their anti-proliferative activities. The RBA values reflect how the molecule can fit into the LBD and the interactions with the surrounding amino acids. Thus, it is correlated to the compound structure [44].

Table 4.

RBA for AR, % antiproliferative effect, IC50 values and (lipophilicity) logPo/w of the nonsteroidal antiandrogen functionalized ferrocene compounds at 72 h. Data from reference 44.

| Compound | RBA (%) AR | % Antiproliferative effect on PC-3 at 10 μM | IC50 (μM) on PC-3 | logPo/w |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicalutamide | 0.29 | 15 | - | 3.4 |

| Nilutamide | 0.15 | 11 | - | 3.2 |

| 1 | 0.52 | 37 | 68 | 5.2 |

| 2 | 0.22 | 34 | 67 | 5.6 |

| 3 | 0.07 | 4 | - | 4.7 |

| 4 | 0.09 | 9 | - | 5.0 |

| 5 | 0.041 | 84 | 5.4 | 6.5 |

| 6 | 0.041 | 76 | 5.6 | 5.7 |

The receptor binding affinity to AR, according to Dalton and coworkers, is related to the hydrogen bonding with T877 and N705 amino acids and how the molecule fits into the binding pocket [45]. For instance, the molecule cannot be completely planar, as is the case for bicalutamide where the rings are positioned at about 90° to each other. This configuration adopted for bicalutamide as well as 1 and 2 apparently are determinant for their affinity to AR. X-ray structure determination of 1 and 2 (Figure 14) revealed that in fact in these compounds, the ferrocenyl is rotated in 68.8° and 61.5° respectively, from the hydantion ring and the hydantion and phenyl rings are not coplanar with angles of 43.8° and 35.8° respectively [44].

Figure 14.

Ortep diagrams of compounds 1 (above) and 2 (below). Reproduced with permission of the American Chemical Society.

From the anti-proliferative data presented in Table 4, it is evident that for hormone-independent PC-3 prostate cancer cell line the anti-androgen compounds, nilutamide and bicalutamide, have no effect on this cell line as well as compounds 3 and 4, whereas compound 5 and the organic analogue, 6, exhibited high antiprolifetative activity. 1 and 2 have moderate anti-proliferative activity on PC-3 cell line. Conversely, in hormone-dependent prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP, the anti-androgen bicalutamide showed low anti-proliferative effect while nilutamide has proliferative effect. Compounds 5 and 6 have approximately the same strong anti-proliferative effect, with IC50 values of 5.4 μM and 5.6 μM respectively. Addition of dehydrotestosterone, DHT, did not affect the activity of 5 and 6 in this hormone-dependent prostate cancer cell line. Therefore, the anti-proliferative activity of the last two species proceeds from the intrinsic cytotoxicity of the compounds rather than from the antiandrogenic effect [44]. The authors conclude that the cytotoxicities of 5 and the organic analogue 6, are related to the aromatic nature of the ferrocenyl and phenyl groups attached to C-5, which increases the lipophilicity of the nilutamide compound and not from the ferrocenyl group (6.5 (5) and 5,7 (6) vs. 3.2 for nilutamide) [44]. It has been observed that an increase in cytotoxicity can be correlated to an increase in lipophilicity [46,47]. In addition, the authors suggest that cannabinoid receptors are possible target because prostate cancer has high level of these receptors.

2.3 Steroid Vectorized Ferrocenes

Recognizing the potential use of ferrocenes vectorized by estradiol in medicine, in 2001 Jaouen and coworkers synthesized 17α-(ferrocenylethynyl)estradiol compound, 1, Chart 4. This compound has stability in aqueous environment and it has good binding affinity to ERα and ERβ (RBA = 28 and 37 % respectively) and can be used as a tracer for immunoassay for antibodies specific to estradiol [48].

Chart 4.

In 2006, a series of ferrocenyl estradiol derivatives (Chart 4) were synthesized and screened for their anti-proliferative effects on hormone-dependent MCF-7 and hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines as well as RBA for ERα [49]. The new species have reasonable RBA for ERα (12–43%). The estradiol substituted at position 7α with ferrocenyl has lower RBA to ERα due to the bulkiness of the ferrocene. At this position, ferrocene produce steric hinderance inside the ligand binding pocket and as a result lower the affinity to ER. This premise was corroborated by Molecular Modeling studies.

At low micromolar concentrations (0.1–1 μM), 1–3 exhibit estrogenic effects in MCF-7 and no effect on MDA-MB-231. At high concentration, 1 and 3 are cytotoxic on MDA-MB-231 (IC50 13.4 and 18.8 μM) while 2 remain inactive [49].

In the following years, steroid vectorized metallocenes remained almost neglected as potential target specific anti-cancer agents. In 2009, the use of metallocenes and semisandwich vectorized with androgens was reported, Chart 5 [50].

Chart 5.

Molecular structures of 5a, 6 and 8 were determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction technique, Figure 15. There are some structural features that deserve to be discussed. First, 5a, 6 and 8 have the organometallic group positioned in the α face of the steroid but differ in their spatial orientation. Compounds 5a and 8 have similar structures where the CpRe(CO)3 and the ferrocenyl are located on the α face and underneath the steroidal C and D rings. In contrast, 6 has the ferrocenyl in the α face but pointing away from the steroid and not under the C and D rings [50]. It could be envisioned that the position of the ferrocenyl in 6 and 8 could account for the dramatic change in the RBA values on AR (Table 5), but the authors do not comment and correlate RBA and these structural differences.

Figure 15.

Solid state structures of 5a, 6 and 8. Reproduced with permission of Organometallics.

Table 5.

RBA for AR, IC50 values and lipophilicity of the steroidal ferrocenyl compounds at 72 h. Data from reference 50.

| Compound | % RBA on AR | IC50 (μM) | log Po/w |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHT | 100 | 3.2 | |

| 4 | 0.57 | 4.7 | 5.28 |

| 5a | 0.073 | - | 5.15 |

| 5b | 0.068 | - | 5.24 |

| 6 | 0.32 | 8.3 | 5.4 |

| 7 | 0.032 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| 8 | 0.020 | 12.2 | ND |

The biochemical studies on these compounds were pursued and compared with testosterone and dehydrotestosterone, DHT. Surprisingly, these species have low RBA (0.073–1.31% compared to DHT, 100%) for AR even though they conserve the 3-keto and 17β-OH functional groups, Table 5. This suggests that the incorporation of the organometallic moiety to the androgens creates a bulky organometallic androgen which cannot fit into the ligand binding pocket of the AR [50].

The anti-proliferative activity of these organometallic androgen derivatives was tested on hormone-independent PC-3 and hormone-dependent LNCaP prostate cancer cells [50]. The ferrocenyls 4–8 have high anti-proliferative activity at 10 μM but modest activity at concentration of 1 μM on PC-3 cells, Table 5. On hormone-dependent LNCaP, only 4 and 6 showed anti-proliferative activity at 10 μM but at low concentration, (1 μM), they have proliferative activity. This suggests that the anti-proliferative activity 4 and 6 at 10 μM could be attributed to a combination of AR recognition and intrinsic cytotoxicity of the ferrocenyl group.

Mansroi and coworkers published a series ferrocenyl vectorized with steroidal derivatives of estrogens and androgens, Chart 6 [51].

Chart 6.

These ferrocenic steroidal compounds (10–14) were screened in human cervical adenocarcinoma cell line (HeLa) and compared to doxorubicin, Table 6 [51]. Ferrocenic testosterone and methyl testosterone derivatives 10 and 11 showed GI50 (50% cell growth inhibition) values corresponding that of doxorubicin, 0.223, 0.271 and 0.250 μg/mL respectively. Testosterone and methyl testosterone showed higher GI50 values, about 2–3 times higher than GI50 values of 10, 11 and doxorubicin. This indicates that testosterone and methyl testosterone possess lower anti-proliferative activity than 10, 11 and doxorubicin. Also 13 and 14 showed anti-proliferative activities corresponding to half of the anti-proliferative activity of doxorubicin, while their parent compounds, 17-pregnenolone and estrone, showed low anti-proliferative activities on HeLa cells. This suggests that the functionalization of the hormones by the ferrocenic moiety increase their anti-proliferative activities. This has a great potential to treat hormone-dependent cancers.

Table 6.

GI50, SC50 and MC50 values for the ferrocenic steroidal derivatives on HeLa cell line at 24 h. Data from reference 51.

| Compound | GI50 (μg/mL) | SC50 (mg/mL) | MC50 (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 10 | 0.223 | 0.243 | 0.160 |

| Testosterone | 0.750 | ND | ND |

|

| |||

| 11 | 0.271 | 0.359 | 0.320 |

| Methyltestosterone | 0.619 | ND | ND |

|

| |||

| 12 | 1.720 | 6.890 | 2.030 |

| Androsterone | 2.700 | ND | ND |

|

| |||

| 13 | 0.405 | 4.240 | 4.520 |

| 17-hydroxypregnelonone | 1.830 | ND | ND |

|

| |||

| 14 | 0.505 | 4.740 | 2.860 |

| Estrone | 3.410 | ND | ND |

|

| |||

| 15 | - | 0.760 | 0.610 |

| Prednisolone | ND | ND | |

|

| |||

| 16 | - | 0.950 | 0.980 |

| Hydrocortisone | ND | ND | |

To understand the anti-proliferative activity of these species, their anti-oxidative activities were studied by determining the scavenging and chelating profiles. All the functionalized steroids presented free radical scavenging and metal ion chelating activities while the hormones are inactive. Compound 10 has the highest scavenging activity among the steroidal derivatives but lower than vitamin C (0.021 μg/mL) and ferrocenic carboxaldehide (0.12 μg/mL). Furthermore, all the compounds exhibited lower chelating activity than EDTA (MC50 0.030 μg/mL). Thus, according to the authors, the scavenging and chelating activities of the ferrocenic steroidal compounds are centered on the ferrocenyl group. These two anti-oxidative activities are responsible for the high anti-proliferative activity on HeLa cell line. 15 and 16 showed anti-inflammatory activities similar to their parent compounds, prednisolone and hydrocortisone, with 80.99 % and 68.24 % edema inhibition respectively. Among the ferrocenic steroidal compounds studied, 10 have the greatest potential to be further developed as an anti-cancer drug [51].

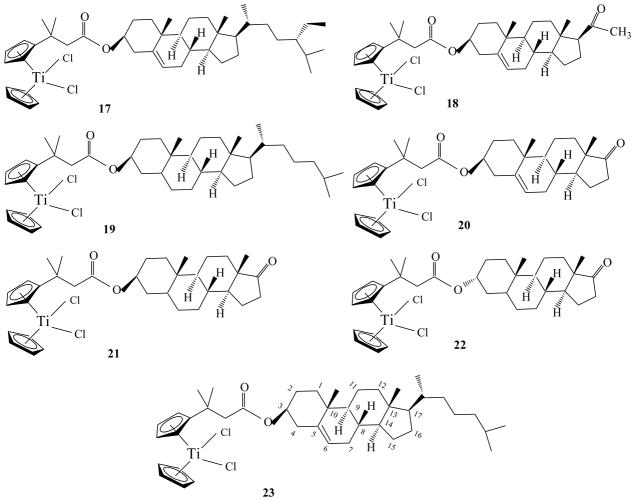

In 2010 Meléndez and coworkers reported the synthesis and anti-proliferative activity of steroid-functionalized titanocenes with sex steroids and cholesterol derivatives as potential vectors to develop anti-cancer drugs, Chart 7 [52]. In principle, sex steroids as pendant groups (vectors) could provide more selectivity to specific cancer cells, potentially producing target-specific anti-cancer drugs, in particular to hormone-dependent cancers.

Chart 7.

The selection of the pendant groups was based on their biological activity as follow. Androsterone (22) and its epimer, trans-androsterone (21) belong to a group of natural androgens produced by the enzyme 5α-reductase from the adrenal hormone dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) [53]. Androsterone is a hormone with weak androgenic activity and it is a product of the metabolism of testoterone whereas trans-androsterone is a more active species and has been used as a steroid hormone drug due to its inhibitory effects on breast cancer [53]. DHEA is a natural steroid hormone produced by the adrenal glands, gonads, adipose tissue and the brain. DHEA is the most abundant hormone in the human body and it is a precursor of androstenedione, testosterone, estradiol and estrone. It can interact on the androgen receptor directly [53,54]. DHEA has inhibitory effects on breast cancer. Pregnenolone can be enzymatically converted to progesterone. Cholesterol and dehydrocholesterol are precursors of steroid hormones [55]. Clionasrerol is natural product analog of cholesterol. The entire sex steroid derivatives selected pendant groups are biologically important compounds.

The seven titanocenyl steroid compounds were structurally characterized. Due to the lack of crystal structures of these compounds, the structures of 18, 21 and 22 were calculated using density functional theory (DFT), Figure 16. Briefly, the compounds have distorted tetrahedral geometries and the steroids are positioned away from the chlorides but they have different stereochemistry on the substituted Cp ring, differing in the steroid position. 18 and 21 are similar in structure, with the pendant groups pointing upward of the Cp ligand plane, avoiding possible steric interactions with the chlorides, whereas 22 showed the steroid in the opposite direction, most likely as a result of its original steroidal configuration on C-3. However, the steroid is rotated about 78° away from the chlorides avoiding steric interactions.

Figure 16.

Calculated structures of titanocenyl– pregnenolone (18), trans-androsterone (21) and androsterone (22). Reproduced with permission of J. Biol. Inorg. Chem.

The anti-proliferative activity of 17–23 was determined in colon cancer HT29 and breast cancer MCF-7 cell lines, Table 7. In general, all the functionalized titanocenyls are more active than titanocene dichloride. Furthermore, two groups of titanocenyl can be recognized: titanocenyls containing cholesterol rings with IC50 values over 200 μM, with the exception of complex (17) and highly active titanocenyls containing sex steroids with IC50 values below 50 μM on MCF-7 cell line. It should be pointed out that the higher cytotoxic complexes are those containing sex steroid derivatives whereas those including cholesterol unit (17,19 and 23) showed less cytotoxicity.

Table 7.

Antiproliferative activities of complexes 17–23 against HT-29 and MCF-7 cancer cell lines at 72 h. IC50±std. Data from reference 52.

| Compound | IC50(μmol/L), HT-29 | IC50(μmol/L), MCF-7 |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 200 | 34±17 |

| 18 | 16.2±0.3 | 20±2 |

| 19 | >200 | >200 |

| 20 | 22±1 | 13±2 |

| 21 | 34±11 | 40±25 |

| 22 | 47±3 | 21±5 |

| 23 | >200 | >200 |

| Cp2TiCl2 | 413±2 | 570±5 |

Compounds 17, 19 and 23 are inactive in HT-29 while 17 is active in MCF-7. There is no simple explanation for the difference in anti-proliferative activity between them, except that 17 has a more branch aliphatic side chain on C-17. That is, 17, 19, and 23 have very similar structures but, the cytotoxic activity of 17 on MCF-7 may be explained easily in terms of lipophilicity. 17 has an extra –CH2CH3 group making it more lipophilic. Increase in lipophilicity could facilitate the entry of the drug through the cell membrane [46,47].

Titanocenyls 18, 20 and 22, containing sex steroids, are the most active in both cell lines. Therefore, there is a great potential for 18, 20 and 22 to be studied on hormone-dependent cancers, such as prostate, testicular and ovarian. Among them, 20 (DHEA) is the most active in MCF-7 and it might be a better candidate for a target-specific drug in the treatment of the hormone-dependent cancers. The authors explain the anti-proliferative activity of 20 using the following rationale. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a naturally occurring steroid synthesized in the adrenal cortex, gonads, brain, and gastrointestinal tract, and it is known to have chemopreventive and anti-proliferative actions on tumors, in particular to breast cancer [53,54]. Also, it can act on the androgen receptor directly. Although we could envisage that the compounds containing steroids with ketonic functional groups are more active than those with steroids containing acetyl functional group, it is most likely that the high anti-proliferative activity of 20 comes from the inhibitory effect of the DHEA (vector) on breast cancer rather than due to these structural differences on the steroid (ketonic vs. acetyl groups).

More recently, Meléndez and collaborators published a series of ferrocenes functionalized with estrogens and vitamin D2 (Chart 8) and their anti-proliferative activities were determined on colon cancer HT-29 and hormone-dependent breast cancer MCF-7 cell lines, Table 8. [56]. The pendant groups selected are based on the following criteria. The cell has nuclear receptors for ER and vitamin D. In particular, estradiol and estrone are estrogens that are recognized by the estrogen receptor. As MCF-7 cells express higher amount of ER, these vectors (estrogens) potentially can be recognized the receptor and facilitate the entry of the ferrocenyl moiety inside the cell. If the vector is recognized by the receptor, the vectorized ferrocene can behave as a target-specific (receptor-specific) drug for hormone-dependent cancers. Likewise, ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) undergoes an enzymatic process to yield Vitamin D. The cell also has a vitamin D receptor (VDR) that can potentially recognize this vectorized ferrocene making it as a receptor-specific drug.

Chart 8.

Table 8.

Cytotoxicities of the ferrocenoyl esters studied on MCF-7 breast cancer and HT-29 colon cancer cell lines, as determined by MTT assay at 72 h of drug exposure. Data from reference 56.

| Complex | IC50 × 10−6 M, MCF-7 | IC50 × 10−6 M, HT-29 |

|---|---|---|

| Ferocenoyl (3β,5Z,7E,22E)-9,10-secoergosta 5,7,10(19),22-tetraen-3-olate | 1326(110) | 346(50) |

| Ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate | 9(2) | 24.4(6) |

| Ferrocenoyl 3β-estra1,3,5(10)-trien-17-one-3-olate | 108(7) | n/a |

| Ferrocenium tetrafluoroborate | 150 | 180 |

The anti-proliferative activity of these species were determined and compared to Fc+. In hormone-dependent MCF-7 cells, the ferrocenoyl esters (ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate (estradiol ferrocenoylate), 24, and ferrocenoyl 3β-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-one-3-olate (estrone ferrocenoylate), 25, are more active than Fc+. In marked contrast, ferrocenoyl (3β,5Z,7E,22E)-9,10-secoergosta-5,7,10(19),22-tetraen-3-olate (ergocalciferol ferrocenoylate), 26, showed the lowest anti-proliferative activity among the series. In colon cancer HT-29 cells, only ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate (estradiol ferrocenoylate) revealed to be more active than Fc+. It should be mentioned that estradiol ferrocenoylate showed the highest activity in both cell lines [56]. Therefore, this compound was studied in more details to explain its high anti-proliferative activity.

To explain the high activity of estradiol ferrocenoylate, and if the estradiol as pendant group is working as a vector of ferrocene, docking studies between the ERα and the above complex were performed. It is known that receptor agonist must fit into the ligand binding pocket of the receptor whereas the antagonist may reside either in the pocket or in other location but must induce a conformational change in the protein structure, inactivating the receptor.

Prior to the ducking studies, the structure of estradiol ferrocenoylate was calculated using DFT and the lowest energy conformation determined, Figure 17a. This structure was incorporated into the LBD of ERα for docking studies.

Figure 17.

Conformations of ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate a) lowest energy conformer b) conformation inside the receptor. Reproduced with permission of Dalton Transaction.

The docking studies demonstrated that the lowest energy structure (conformation) is when estradiol ferrocenoylate resides away from the β-estradiol binding pocket. Estradiol ferrocenoylate docks between helix 1 and helix 5 and cannot fit into the pocket due to the steric hindrance with ferrocenoyl moiety, Figure 18. The initial structure tested where the ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate is residing into the β-estradiol binding pocket is highly energetic [56]. As a reference, estradiol (natural estrogen ligand) docks between helix 3 and helix 5 [57].

Figure 18.

Representation of the interaction of ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate in the ERα LBD. The complex structure is colored violet. Reproduced with permission of Dalton Transaction.

In terms of close contact (3.5Å or less), PRO 324, PRO 325, ILE 326, GLU 353, MET 357, ILE 386, GLY 390 and ARG 304 get involved in hydrophobic interaction with the Cp rings. The estradiolate (pendant group) is not positioned in the typical estradiol binding pocket and instead it is surrounded by LEU 320, GLU 323, TRP 393, ARG 394, and LYS 449. For β-estradiol (E2, natural estrogen ligand), the phenol gets involved in hydrogen bonding with GLU 353 and ARG 394, whereas C-17 hydroxyl group does hydrogen bonding with HIS 524. In addition, β-estradiol is surrounded by LEU 346, LEU 349, ALA 350, LEU 354, LEU 387, MET 388, LEU 391, PHEN 404, GLU 419, LEU 428, LEU 525 and LEU 540 providing a hydrophobic environment [56].

One interesting point obtained from this docking studies is that the conformation of the estradiol ferrocenoylate adopted inside the LBD, Figure 17b, is not the lowest energy conformation (Figure 17a) according to the structure calculation by DFT. It is evident that this higher energy conformation adopted in the LBD is stabilized by the hydrophobic interactions with the surrounding amino acids as explained above. It is not a surprise that estradiol ferrocenoylate docks on a different place with respect to estradiol. First, the compound does not have the C-3 hydroxyl group to get engaged in hydrogen bonding with GLU 353 and ARG 394. In addition, ferrocene is sterically demanding and hinder the entrance of the compound inside the LBP. The authors mentioned the possibility of estradiol ferrocenoylate inducing changes in the protein conformation (LBD) inactivating the estrogen receptor and the ferrocene expressing its cytotoxic activity. That could explain the anti-proliferative activity of estradiol ferrocenoylate. Although this hypothesis has not been tested, recent confocal microscopy studies in MCF-7 have shown that estradiol ferrocenoylate enters into the cell and reaches the nucleus, after two hours of drug exposure, Figure 19. Therefore, the recognition of estradiol ferrocenoylate by the ER cannot be ruled out and remains to be studied in more details.

Figure 19.

Internalization of Ferrocenoyl-estradiol on MCF-7 breast cancer cell line using Confocal Microscopy after 2 hours of drug exposure -

are estradiol ferrocenoylate (of ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate),

are estradiol ferrocenoylate (of ferrocenoyl 17β-hydroxy-estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-olate),

is the nucleus.

is the nucleus.

3. Concluding remarks

We have reviewed general aspects of metallocenes vectorized with either hormone derivatives or selective endocrine modulator (SEM). The use of metallocenes as metal-based drugs or for metallo-immunoassay was clearly demonstrated across this review. In terms of functionalized metallocenes as anti-cancer drugs, vectorizing the organomentallic unit with hormones or SEM can certainly yield highly active compounds for hormone-dependent and independent cancers. There are conflicting results regarding the anti-proliferative activity of metallocene vectorized with hormone, whether or not they retain affinity to the receptor as well as preserve the cytotoxic effects making target-specific drugs. This subject needs to be investigated in further details. Also other receptors can be target of these vectorized ferrocenes such as cannabinoid receptors as suggested by Jaouen group. One could envision a vectorized metallocene with molecules that facilitate the entry and enable the metallocene to cross the blood brain barrier, producing anti-cancer drugs for brain tumors.

Scheme 1.

Research Highlights.

Metallocenes vectorized with hormones can be recognized by the hormone receptor.

Metallocenes vectorized with selective receptor modulator can express antagonist behavior.

Metallocenes vectorized with hormones can be used as makers in metalloimmunoassays.

Acknowledgments

E.M. acknowledges the NIH-MBRS SCORE Programs at the University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez for financial support via NIH-MBRS-SCORE Program grant #S06 GM008103-37, my research group in particular to Dr. Li Ming Gao and José Vera. Also E.M. acknowledges the collaboration and scientific advice of Dr. Jaime Matta from Ponce School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Köpf H, Köpf-Maier P. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1979;18:477–478. doi: 10.1002/anie.197904771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Köpf-Maier P. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;47:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00193472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H. Structure and Bonding. 1988;70:103. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H. Chem Rev. 1987;87:1137–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H. In: Metal Compounds in Cancer Therapy, Organometallic Titanium, Vanadium, Niobium, Molybdenum and Rhenium Complexes - Early Transition Metal Anti-tumor Drugs. Fricker SP, editor. Chapman and Hall; London: 1994. pp. 109–146. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding MM, Mokdsi G. Curr Med Chem. 2000;7:1289–1303. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meléndez E. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;47:309–315. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berdel WE, Schmoll H-J, Scheulen ME, Korfel A, Knoche MF, Harstrick A, Bach F, Baumgart J, Sab G. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1994;120(Supp):R172. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korfel A, Scheulen ME, Schmoll H-J, Gründel O, Harstrick A, Knoche M, Fels LM, Skorzec M, Bach F, Baumgart J, Saβ G, Seeber S, Thiel E, Berdel W. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2701–2708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luemmen G, Sperling H, Luboldt H, Otto T, Ruebben H. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:415–417. doi: 10.1007/s002800050838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christodoulou CV, Ferry DR, Fyfe DW, Young A, Doran J, Sheehan TMT, Eliopoulos A, Hale K, Baumgart J, Sass G, Kerr DJ. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2761–2769. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Kröger N, Kleeberg UR, Mross K, Sass G, Hossfeld DK. Onkologie. 2000;23:60–62. [Google Scholar]; b Baumgart J, Berdel WE, Fiebig H, Unger C. Onkologie. 2000;23:576–579. doi: 10.1159/000055009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan VC. J Med Chem. 2003;46:883–908. doi: 10.1021/jm020449y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newling DW. Br J Urol. 1996;77:776–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan VC. Curr Probl Cancer. 1992;16:129–176. doi: 10.1016/0147-0272(92)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decensi AU, Boccardo F, Guarneri D, Positano N, Paolerri MC, Costantini M, Martorana G, Giuliani L. J Urol. 1991;146:377–381. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neri R, Peets E, Watnick A. Biochem Soc Trans. 1979;7:565–569. doi: 10.1042/bst0070565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker H, Crook JW, Chesterson GJ. J Med Chem. 1988;31:954–959. doi: 10.1021/jm00400a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaouen G, Top S, Laconi A, Couturier D, Brocard J. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:2207–2208. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Top S, Jaouen G, Vessières A, Abjean J-P, Davoust D, Rodger CA, Sayer BG, McGlinchey MJ. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6659–6666. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amouri HE, Vessières A, Vichard D, Top S, Gruselle M, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 1992;35:3130–3135. doi: 10.1021/jm00095a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vichard D, Gruselle M, Amouri HE, Jaouen G, Vaissermann J. Organometallics. 1992;11:2952–2956. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vessieres A, Top S, Vaillant C, Osella D, Mornon JP, Jaouen G. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1992;31:753–755. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaouen G, Vessières A. Acc Chem Res. 1995;26:361–369. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Top S, Hafa HE, Vessières A, Quivy J, Vaissermann J, Hughes DW, McGlinchey MJ, Mornon J-P, Thoreau E, Jaouen G. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8372–8380. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Top S, Dauer B, Vaissermann J, Jaouen G. J Organometal Chem. 1997;541:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Top S, Tang J, Vessières A, Carrez D, Provot C, Jaouen G. Chem Commun. 1996;8:955–956. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Top S, Vessières A, Leclercq G, Quivy J, Tang J, Vaissermann J, Huché M, Jaouen G. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:5223–5236. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.a Hillard EA, Vessières A, Jaouen G. Top Organomet Chem. 2010;32:81–117. [Google Scholar]; b Gasser G, Ott I, Metzler-Nolte N. J Med Chem. 2011;54:3–25. doi: 10.1021/jm100020w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vessières A, Top S, Beck W, Hillard E, Jaouen G. Dalton Trans. 2006:529–541. doi: 10.1039/b509984f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaouen G, Top S, Vessieres A, Leclercq G, McGlinchey MJ. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2505–2517. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillard EA, Vessières A, Top S, Pigeon P, Kowalski K, Huché M, Jaouen G. J Organometal Chem. 2007;692:1315–1326. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillard EA, Pigeon P, Vessières A, Amatore C, Jaouen G. Dalton Trans. 2007:5073–5081. doi: 10.1039/b705030e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pigeon P, Top S, Zekri O, Hillard EA, Vessières A, Plamont M-A, Buriez O, Labbé E, Boutamine S, Amatore C, Jaouen G. J Organometal Chem. 2009;694:895–901. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pigeon P, Top S, Vessières A, Huché M, Hillard EA, Salomon E, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2814–2821. doi: 10.1021/jm049268h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Top S, Hafa HE, Vessières A, Huché M, Vaissermann J, Jaouen G. Chem Eur J. 2002;8:5241–5249. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20021115)8:22<5241::AID-CHEM5241>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo M, Sun H, McArdle HJ, Sadler PJ. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10023–10033. doi: 10.1021/bi000798z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun H, Li H, Sadler PJ. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2817. doi: 10.1021/cr980430w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hillard E, Vessières A, Thouin L, Jaouen G, Amatore C. Ang Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:285–290. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vessières A, Top S, Pigeon P, Hillard E, Boubeker L, Spera D, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3937–3940. doi: 10.1021/jm050251o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Top S, Vessières A, Cabestaing C, Laois I, Leclercq G, Provot C, Jaouen G. J Organometal Chem. 2001;637–639:500–506. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen A, Top S, Vessières A, Pigeon P, Huché M, Hillard E, Jaouen G. J Organometal Chem. 2007;692:1219–1225. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plażuk D, Vessières A, Hillard EA, Buriez O, Labbé E, Pigeon P, Plamont M-A, Amatore C, Zakrzewski J, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 2009;52:4964–4967. doi: 10.1021/jm900297x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payen O, Top S, Vessières A, Brulé E, Plamont M-A, McGlinchey MJ, Müller H, Jaouen G. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1791–1799. doi: 10.1021/jm701264d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao W, Bohl E, Dalton JT. Chem Rev. 2005;105:3352–3370. doi: 10.1021/cr020456u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tabbi G, Cassino C, Cavigiolio G, Colangelo D, Ghiglia A, Viano I, Osella D. J Med Chem. 2002;45:5786–5796. doi: 10.1021/jm021003k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Selassie CD, Kapur S, Verma RP, Rosario M. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7234–7242. doi: 10.1021/jm050567w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osella D, Nervi C, Galeotti F, Cavagiolio G, Vessières A, Jaouen G. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2001;84:3289–3297. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vessières A, Spera D, Top S, Misterkiewicz B, Heldt J-M, Hillard E, Huché M, Plamont M-A, Napolitano E, Fiaschi R, Jaouen G. Chem Med Chem. 2006;1:1275–1281. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Top S, Thibaudeau C, Vessières A, Brulé E, Le Bideau F, Joerger J-M, Plamont M-A, Samreth S, Edgar A, Marrot J, Herson P, Jaouen G. Organometallics. 2009;28:1414–1424. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manosroi J, Rueanto K, Boonpisuttinant K, Manosroi W, Biot C, Akazawa H, Akihisa T, Issarangporn W, Manosroi A. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3937–3943. doi: 10.1021/jm901866m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao LM, Vera JL, Matta J, Meléndez E. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:851–859. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0649-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Labrie F. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:118–130. doi: 10.1080/09513590600624440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshida S, Honda A, Matsuzaki Y, Fukushima S, Tanaka N, Takagiwa A, Fujimoto Y, Miyazaki H, Salen G. Steroids. 2003;68:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.May W, Lemaire V, Malaterre J, Rodriguez JJ, Cayre M, Stewart MG, Kharouby M, Rougon G, Le Moal M, Piazza PV, Abrous DN. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;26:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vera JL, Gao LM, Santana A, Matta J, Meléndez E. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:9557–9565. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10995b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wurtz JM, Egner U, Heinrich N, Moras D, Muller-Fahrnow A. J Med Chem. 1998;41:1803–1814. doi: 10.1021/jm970406v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]