Abstract

Aloe littoralis Baker (Asphodelaceae family) is a well known plant in southern parts of Iran. Because of its use in Iranian folk medicine as a wound-healing agent, the present study was carried out to investigate anti-inflammatory and wound healing activities of this plant in Wistar rats. A. littoralis raw mucilaginous gel (ALRMG) and also two gel formulations prepared from the raw mucilaginous gel were used in this study. Gel formulations (12.5% and 100% v/w Aloe mucilage in a carbomer base) were applied topically (500 mg once daily) for 24 days in the thermal wound model. Also Aloe gel formulation (100%) and ALRMG (500 mg daily) were evaluated in incisional wound model. Carrageenan-induced paw edema was used to assess the anti-inflammatory effect of intraperitoneal injection of ALRMG. In burn wound, ALRMG and Aloe formulated gel (100%) showed significant (P<0.05) healing effect. Topical application of ALMRG and Aloe formulated gel (100%) promoted healing rate of incisional wound. In carrageenan test, ALRMG (2.5 and 5 ml/Kg) revealed significant (P<0.05) anti-inflammatory activity. Results showed that A. littoralis is a potential wound-healing and anti-inflammatory agent in rats. Further studies are needed to find out the mechanism of these biological effects and also the active constituents responsible for the effects.

Keywords: Aloe littoralis, Asphodelaceae, Mucilage, Wound healing, Anti-inflammatory

INTRODUCTION

Aloe littoralis Baker is a unique living member of plants of the genus Aloe (Asphodelaceae family, formerly Liliaceae) in Iran(1). A. littoralis is comprising more than 350 till 600 species which grow in the warm areas of the world(2,3). Although A. vera as a typical species of this genus is cultivating in Iran, A. littoralis wildly grown and distributed in several parts of Iran like southern provinces and Persian gulf islands(1,4).

It is a succulent herb that has elongated and pointed leaves. A. littoralis and A. vera which commonly known in Iran as “Sabre Zard”, “Sebr” or “Segel”, have been used in Iranian traditional and folk medicine to treat several disorders including some dermatological, gastrointestinal and inflammatory diseases. Rhazes, Ebn-e Sina and Hakim Momen as three famous Persian scientists were also familiar with this plant and mentioned its wound and burn healing and anti-inflammatory activities in their manuscripts(5–7). Aloe plants contain hydroxyanthracene and chromone derivatives and mucilaginous liquid gel(2,3,8,9). A few reports on the chemical analysis of A. littoralis anthraquinones have been published. A. littoralis have revealed the presence of several related glycosylated oxanthrones, littoralin and deacetyllittoralin and the absence of the common constituents of the Aloe genus, namely, aloin(10,11).

The aim of the present work was to evaluate the wound healing and anti-inflammatory effects of A. littoralis as the unique wild native species of Aloe in Iran, in rats using the wound models and carrageenan-induced paw edema tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and preparation of gel

A. littoralis mature and full size leaves growing wildly in Minab, a city near to the straits of Hormoz, in southern Iran belonging to the Hormozgan province (Iran) were collected at an altitude of about 40 m on March. The leaves were washed and rinds were removed. A. littoralis raw mucilaginous gel (ALRMG) was obtained mechanically from the parenchyma tissue in the centre of the leaves. Proper preservation and stabilization of the mucilage was achieved by addition of some preservatives and antioxidants and then was kept at a fridge(12). Two gel formulations containing 12.5 and 100% raw mucilaginous gel of the herb were also prepared using 1.5% carbomer 934(13).

The plant identity as A. littoralis was confirmed by the Botany Department of Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Co., Kashan, Iran. A voucher specimen of the plant was deposited in this herbarium for future evidence (Herbarium number: 158-1).

Chemicals

Ketamine hydrochloride was purchased from Park-Davis Company (France). Carrageenan lambda (Sigma, USA) was used for induction of paw edema. Indomethacin and the other chemicals were purchased from Merck Company (Germany). Silver sulfadiazine cream (1% w/w) was provided by Verouskoua (Slovenia).

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 180-220 g were used in groups of six. Animals were maintained in standard laboratory conditions at animal house of School of Pharmacy, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Isfahan, Iran) with free access to food and water. Each animal was housed individually in a single cage to prevent licking or biting of wound areas by other animals. All experiments were carried out in accordance with local guidelines for the care of laboratory animals of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Isfahan, Iran).

Thermal burn wound induction

Thermal burn wound was induced according to the method described by Junger and coworkers(14). Briefly animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (125 mg/kg). The dorsal skin was prepared by removing the hair with electric clippers. Hot stainless steel plates (200°C) with surface area of 1.5 cm2 were put on animal back, 5 cm apart from tail and 1 cm from dorsal line for 20 s. Three days later necrotized tissues were gently removed. Burns were treated with vehicle or test formulations. The wound area was measured by Millipore transparent tapes at 3 day intervals and percent of wound healing was calculated for each interval using the following formula:

Percent of wound healing = [(initial wound area – unhealed wound area) / initial wound area] * 100

Linear incisional wound induction

Eighteen rats were equally divided into three groups. After anesthesia with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (125 mg/kg), one incision, 6 cm in length was made through the skin and subcutaneous muscles on the dorsal midline of animals. The incisions were closed with sutures 1 cm apart(15). One group was control and received vehicle (gel base). Second and third groups treated daily with Aloe gel formulation (100%) and ALRMG, respectively until complete healing. Percent of wound healing was calculated using the following formula:

Percent wound healing = [(wound length before treatment–wound length after treatment) / length of wound before treatment] * 100

Total time required for complete healing was also recorded.

Anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory activity was evaluated by the carrageenan-induced paw edema test in the rats(16,17). Male wistar rats (160-200 g) were briefly anaesthetized with ether and injected subplantarly into right hind paw with 0.1 ml of 1% (w/v) suspension of carrageenan in isotonic saline. The left hind paw was injected with 0.1 ml saline and used as a control. Paw volume was measured prior and 4 h after carrageenan administration using a mercury plethysmorgraph (Ugo Basil, Italy).

ALRMG (2.5 and 5 ml/kg, i.p.) administered 30 min prior to carrageenan injection. The control group received normal saline. A group of animals as positive control received indomethacin (10 mg/kg, i.p.).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan test was used for comparison of data and P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS for windows (SPSS 13) software.

RESULTS

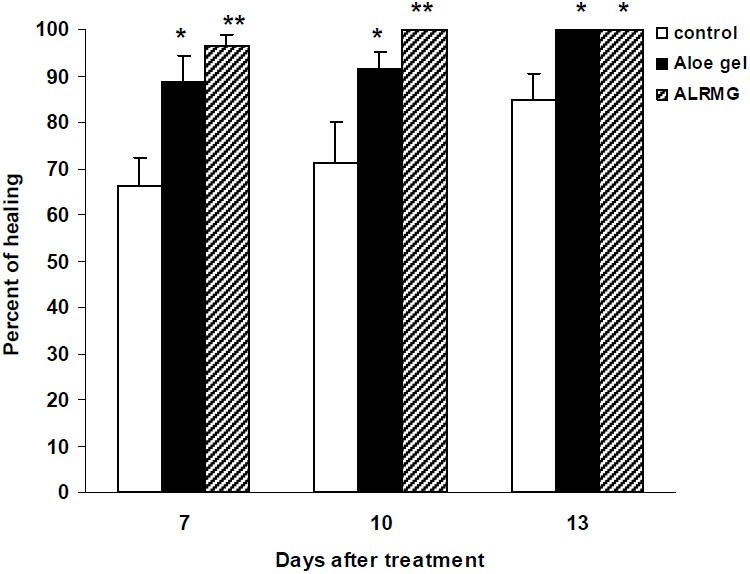

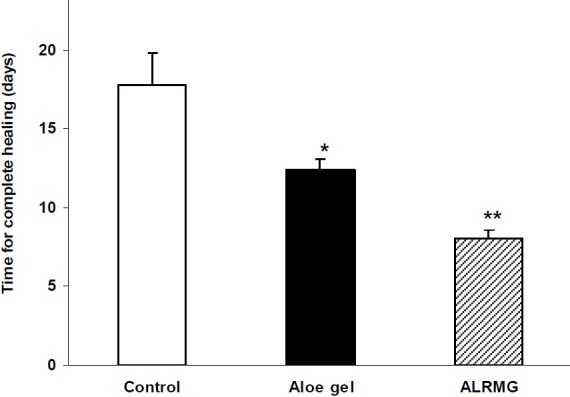

The results of healing effect of ALRMG and gel formulation (100%) on incisional wound are shown in Fig. 1. The process of healing in animals treated with Aloe gel formulation and ALRMG was faster when compared with control group so that ten days after treatment, rate of healing of incisional wound was 71.1%, 91.7% and 100% in control, Aloe gel formulation- and ALRMG-treated groups, respectively. After 13 days treatment Aloe gel-treated animals also revealed complete healing while the healing rate in control group was 85%. Time required for complete healing of the incisional wound is shown in Fig. 2. Aloe gel formulation and ALRMG significantly (P<0.05 for Aloe gel and P<0.01 for ALRMG) reduced the time required for complete healing of the wounds.

Fig. 1.

Healing effect of Aloe littoralis gel and extract on incisional wound. Control group received vehicle (gel base). In second and third groups, Aloe gel formulation (100%) and ALRMG (500 mg daily) were applied topically on the incisional wound until complete healing. Healing rate was calculated 7, 10 and 13 days after induction of incisional wound. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of six rats per group. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01 compared to control group. ALRMG; A. littoralis raw mucilaginous gel

Fig 2.

Time required for complete healing of incisional wound after application of Aloe littoralis gel and extract. An incision, 6 cm in length was made through the skin and subcutaneous muscles on the dorsal midline of animals. Control group received vehicle (gel base). In second and third groups, Aloe gel formulation (100%) and ALRMG (500 mg daily) were applied topically on the incisional wound until complete healing. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of six rats per group. *P<0.05 and ** P<0.01 compared to control group. ALRMG; A. littoralis raw mucilaginous gel.

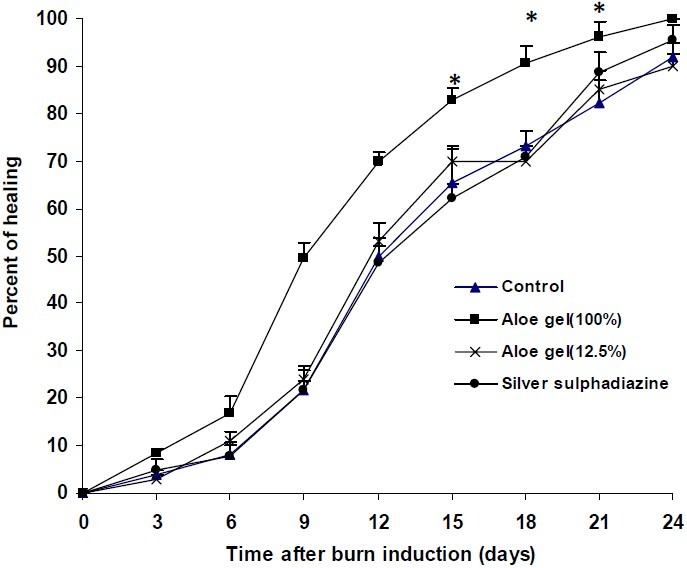

The results of healing properties of A. littoralis gel formlations on thermal burn wounds have been shown in Fig. 3. Treatment of animals with Aloe gel (100%) produced a significant (P<0.05) increase of healing rate of burn wounds when compared with control group. The rate of healing of burn wounds in animals treated with silver sulfadiazine cream (1% w/w) or Aloe gel (12.5%) was not significantly different from that of control group.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Aloe littoralis gel formulations on thermal burn wound. Thermal burn wound was induced by putting hot plates (200°C) with surface area of 1.5 cm2 on animal back. After removal of necrotized tissues, vehicle (gel base), Aloe gel formulations (12.5 and 100%) and silver sulfadiazine cream (500 mg daily) were applied topically on burns in different groups. On 6th day and thereafter at intervals of 3 days, the burn area was measured and healing rate was calculated as follows: Percent of wound healing = [initial wound area – unhealed wound area / initial wound area] * 100. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of six rats per group. * P<0.05 compared to control group.

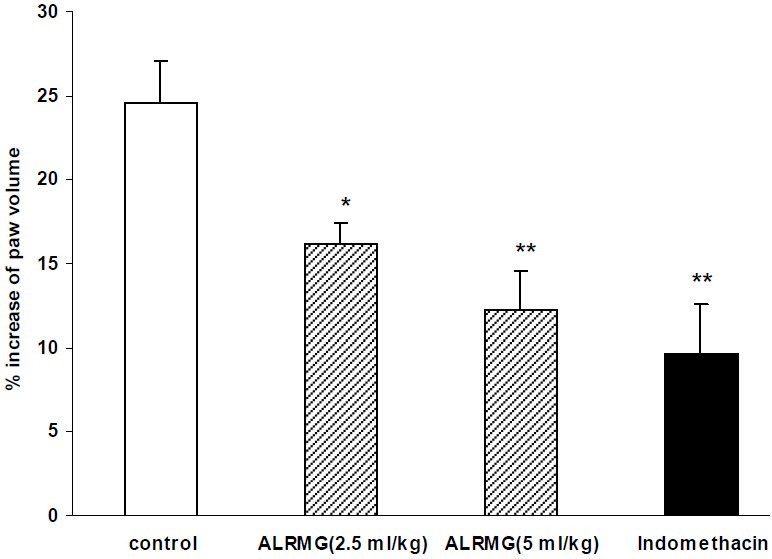

Results of carrageenan test showed that ALRMG at both doses (2.5 and 5 ml/kg) had significant (P<0.05) anti-inflammatory activity (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Anti-inflammatory effect of Aloe littoralis in carrageenan-induced paw edema. Vehicle, ALRMG (2.5 and 5 ml/kg) and indomethacin (10 mg/kg) were injected i.p. 30 min prior to subplantar injection of carrageenan into the right hind paw of rats. Paw volume was measured before and 4 h after carrageenan by a mercury plethysmograph and percent increase in paw volume was calculated and used as an index of inflammation. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of six rats per group. * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01 compared to control group. ALRMG; A. littoralis raw mucilaginous gel.

DISCUSSION

Most of the therapeutic uses of Aloe species can be justified by its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating activities(2). The results of the present study clearly indicate that A. littoralis accelerates wound healing in rats. Although the wound healing properties of Aloe vera and some other species of Aloe have been reported frequently in recent years(2,3,18–21), it is the first time to report similar results for A. littoralis. As it is seen in Figs. 1 and 2, the healing rate of ALRMG is faster than Aloe gel formulations and it might be due to entrapping of active constituents in carbomer network produced by this gel-forming agent. Also there might be some interactions between carbomer and active constituents of A. littoralis. Unlike Aloe gel formulation (100%), a 12.5% preparation was ineffective in the burn wound model and it is because of insufficient concentration. Of course it would be better to examine concentrations between 12.5 and 100 to have a more definite view about the minimum effective concentration which could be considered as a limitation for this study.

The process of wound healing can be broadly categorized into three stages; inflammatory phase (consisting of homeostasis and inflammation); proliferative phase (consisting of granulation, contraction and epithelialization) and finally the maturation phase which determines the strength and appearance of the healed tissue(22). Biosynthesis of new collagens by fibroblasts has a key role in the healing process. Collagen deposition helps the wounds to gain tensile strength during repair(23). Also it has been reported that matrix metalloproteinase-1(MMP-1) which is involved in the degradation of the extracellular matrix, has some role in tissue remodeling(24). Another important factor in the wound repair process is transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) which has three isoforms TGF-β1, β2, and β3. These factors release from platelets at the site of injury and activate and infiltrate fibroblasts, macrophages and neutrophils and initiate wound tissue repair phase. In turn, these cells migrate into the wound site and release cytokines/chemokines that initiate granulation tissue formation(25).

This study was a preliminary study showing that A. littoralis like the well-known species, Aloe vera has wound healing activity, however, it is not clear for us which of above mechanisms or factors is (are) involved in its healing property and further studies are needed.

It has been reported that some of the constituents of Aloe species have potent wound healing and anti-inflammatory actions on some phases of wound and inflammation(26). The polysaccharides of mucilaginous gel are considered to be the active ingredients for Aloe's anti-inflammatory and immune modulatory effects(27).

It has also been reported that Emodin extracted from Rheum officinale has wound healing properties(28). The same anthraquinone compound may also be found in exudates of various Aloe species including A. littoralis. Therefore it seems that at least a part of wound healing effects of A. littoralis is due to the presence of Emodin. Duansak and coworkers reported that Aloe vera can inhibit the inflammatory process following burn injury by reducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-alpha and IL-6) and also leukocyte migration(29). Although we have not measured the levels of these cytokines, they may contribute in anti-inflammatory and wound healing properties observed in our work.

CONCLUSION

The results of the current study indicated that A. littoralis is a potential wound-healing and anti-inflammatory agent in rat models of wound and inflamation. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of action and the nature of the chemically active constituents responsible for the wound healing and anti-inflammatory activities of A. littoralis mucilage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was financially supported by Research Concil of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran and R & D section of Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Co., Kashan, Iran. Plant and gel samples were also provided by this company. We are also grateful to Dr. H. Salehi for his technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mazaffarian V. A Dictionary of Iranian Plant Names. Tehran: Farhang-e Moaser Publications; 1996. p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canigueral S, Vila R. Aloe. British J Phytother. 1993;3:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capasso F, Borrelli F, Capasso R, Di Carlo G, Izzo AA, Pinto L, et al. Aloe and Its Therapeutic Use. Phytother Res. 1998;12:S124–S127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soltanipoor MA. Introduction to the Flora, Life Form and Chorology of Hormoz Island Plants, S. Iran. Rostaniha. 2006;7:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zakariyae Rhazi M. In: Alhawi. Afsharypuor S, translator. Tehran: Iranian Academy of Medical Sciences Publications; 2005. pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebn-e Sina A. In: Ghanoon dar teb. Sharafkandi A, translator. Vol. 2. Tehran: Soroosh Press; 1988. pp. 286–287. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonekaboni SMM. Tohfatol Momenin. Tehran: Nashr-e Shahr; 2007. pp. 283–284. 653. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zargari A. Medicinal Plants. Vol. 4. Tehran: Tehran University Publications; 1990. pp. 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wichtl M. In: Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. Bisset NG, translator. Stuttgart: Medpharm Scientific Publishers; 1994. pp. 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karagianis G, Viljoen A, Waterman PG. Identification of major metabolites in Aloe littoralis by high-performance liquid chromatography-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Phytochem Anal. 2003;14:275–280. doi: 10.1002/pca.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagne E, Van Wyk BE, Stephenson D, Steglich W. Three oxanthrones from Aloe littoralis. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:1683–1687. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramachandra CT, Srinivasa Rao P. Processing of Aloe vera leaf gel: A review. American J Agricult Biol Sci. 2008;3:502–510. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zolfaghari B, Ghannadi A, Moshkelgosha V, Monirifard R, Dehghan M, Enshaeieh Sh, et al. Clinical trial of efficacy of a combined herbal remedy on herpes labialis. Urmia Med J. 2011;22:315–321. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junger H, Moore AC, Sorkin LS. Effects of full-thickness burns on nociceptor sensitization in anesthetized rats. Burns. 2002;28:772–777. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunaiski V, Belford DA. Contribution of circulating IGF-I to wound repair in GH-treated rats. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2002;12:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajhashemi V, Ghannadi A, Sedighifar S. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of the hydroalcoholic, polyphenolic and boiled extracts of Stachys lavandulifolia. Res Pharm Sci. 2007;2:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghannadi A, Hajhashemi V, Jafarabadi H. An investigation of the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Nigella sativa seed polyphenols. J Med Food. 2005;8:488–493. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emami A, Shams Ardekani MR, Mehregan I. Color atlas of medicinal plants. Tehran: ITMRC publications; 2004. p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosseinimehr SJ, Khorasani G, Azadbakht M, Zamani P, Ghasemi M, Ahmadi A. Effect of Aloe cream versus silver sulfadiazine for healing burn wounds in rats. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takzare N, Hosseini MJ, Hasanzadeh G, Mortazavi H, Takzare A, Habibi P. Influence of Aloe vera gel on dermal wound healing process in rat. Toxicol Mech Meth. 2009;19:73–77. doi: 10.1080/15376510802442444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew Ch. The efficacy of Aloe vera used for burn wound healing: a systematic review. Burns. 2007;33:713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo T. Timing of skin wounds. Leg Med. 2007;9:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Z, Wang Z, Shi Y, Lin Z, Jiang H, Hou T, et al. Modulation of collagen synthesis in keloid fibroblasts by silencing Smad2 with siRNA. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1328–1337. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000239537.77870.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Jung E, Lee J, Huh S, Hwang CH, Lee HY, et al. Emodin inhibits TNF alpha-induced MMP-1 expression through suppression of activator protein-1 (AP-1) Life Sci. 2006;79:2480–2485. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin P. Wound healing-aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew C. The efficacy of Aloe vera used for burn wound healing: A systematic review. Burns. 2007;33:713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinson JA, Al Kharrat H, Andreoli L. Effects of Aloe vera preparations on the human bioavailability of vitamins C and E. Phytomed. 2005;12:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang T, Yin L, Yang J, Shan G. Emodin, an anthraquinone derivative from Rheum officinale Baill, enhances cutaneous wound healing in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;567:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duansak D, Somboonwong J, Patumraj S. Effects of Aloe vera on leukocyte adhesion and TNF-alpha and IL-6 levels in burn wounded rats. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2003;29:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]