Abstract

Marker assisted backcrossing has been used effectively to transfer the submergence tolerance gene SUB1 into popular rice varieties, but the approach can be costly. The selection strategy comprising foreground marker and phenotypic selection was investigated as an alternative. The non-significant correlation coefficients between ranking of phenotypic selection and ranking of background marker selection in BC2F1, BC3F1 and BC3F2 generations indicated inefficiency of phenotypic selection compared to marker-assisted background selection with respect to recovery of the recipient genome. In addition, the introgression size of the chromosome fragment containing SUB1 was approximately 17 Mb, showing the effects of linkage drag. The significant correlation coefficient between rankings of phenotypic selection with the percentage of recipient alleles in the BC1F1 generation suggested that background selection could be avoided in this generation to minimize the genotyping cost. The phenotypically selected best plant of the BC3F1 generation was selfed and backcross recombinant lines were selected in the resulting BC3F4 generation. The selection strategy could be appropriate for the introgression of SUB1 QTL in countries that lack access to high-throughput genotyping facilities.

Keywords: Oryza sativa L., submergence tolerance, marker assisted selection, backcrossing

Introduction

Among the marker-assisted selection schemes, marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC) is the most appropriate method for incorporating a major gene or quantitative trait locus (QTL) into a popular variety. Three levels of selection may be applied during MABC: foreground selection, using markers for efficient target gene selection; recombinant selection, which is to minimize linkage drag; and background selection, which is the precise recovery of the recurrent parent genome by using ‘background’ markers, or markers indicating the recurrent (or recipient) parent (Collard and Mackill 2008, Hospital and Charcosset 1997). Conventional backcrossing relies on the use of a screening method for selection of the target locus followed by phenotypic or visual selection for backcross progeny that most closely resemble the recurrent parent. The MABC approach represents a clear advantage over conventional backcross breeding through the development of the ideal genotype in a short period of time, which could not be easily developed through conventional breeding (Septiningsih et al. 2009).

The present study reports MABC for the introgression of a submergence (or flash flood) tolerant QTL designated SUB1, into BR11, the rainfed lowland rice ‘mega variety’ of Bangladesh. SUB1 is a major QTL that explains almost 70% of the phenotypic variance and for which the underlying transcription factor has been identified (Xu and Mackill 1996, Xu et al. 2006). Numerous markers are available for foreground selection of the gene (Neeraja et al. 2007, Septiningsih et al. 2009), which were used in this study.

One disadvantage of MABC is that the method requires a high throughput genotyping facility as well as sufficient resources for marker genotyping. Despite the potential of this method for crop improvement, many developing countries do not have well-developed laboratory facilities, and they lack funds for marker genotyping. Therefore research into ways to reduce the cost of a MABC approach would be extremely useful.

We earlier reported the efficacy of a MABC approach for rapidly introgressing the SUB1 QTL into the mega variety BR11 (Iftekharuddaula et al. 2011). The main objectives of this study were to develop advanced backcross BR11-Sub1 lines and compare the efficiency of phenotypic selection versus marker-assisted background selection at different stages of the backcross process. It was hoped that the data could enable the development of an alternative or modified strategy for introgression of SUB1 into other important rice varieties. A secondary objective of this study was to monitor the introgression size after each backcross generation, for which there are few reports in the literature. The notable exceptions were by Young and Tanksley (1989) and Salina et al. (2003) who determined introgression sizes during backcrossing in tomato and wheat, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and crossing scheme

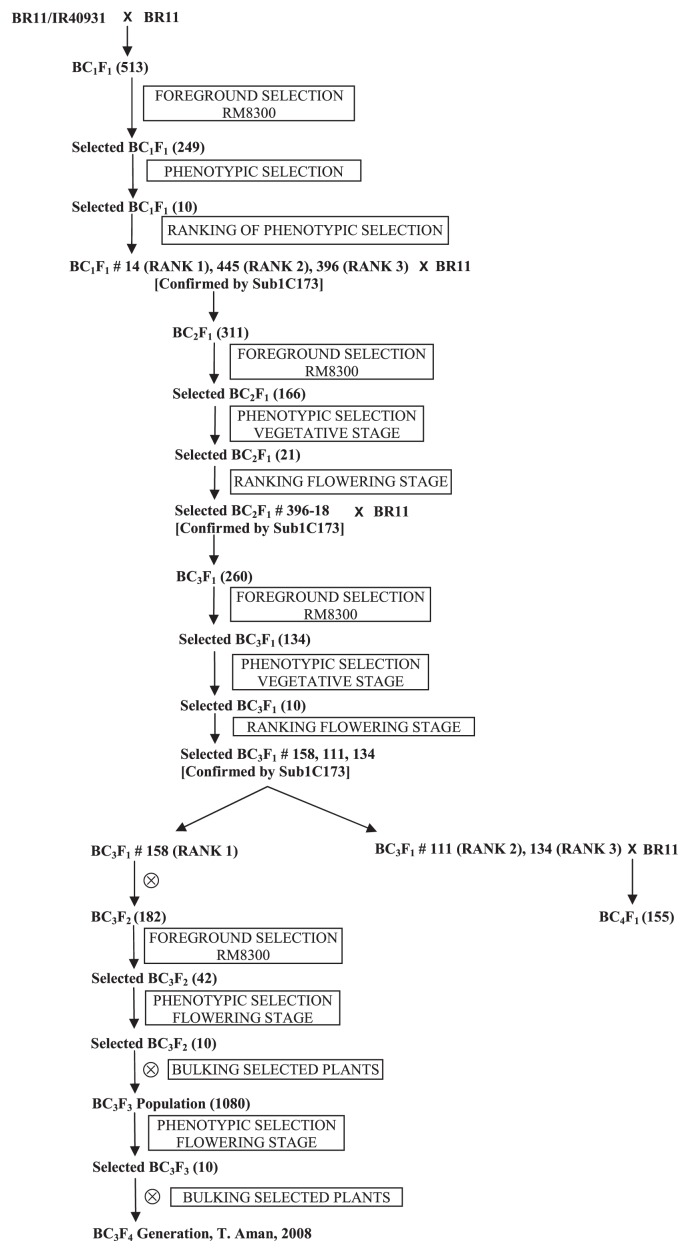

IR40931-33-1-3-2, one of the FR13A-derived submergence-tolerant indica breeding lines (Mackill et al. 1993), was used as the donor of SUB1. The recipient variety was BR11, a widely grown high-yielding rainfed lowland variety in Bangladesh. The donor parent possesses moderately acceptable plant type with around 3.5 ton/ha yield potential. BR11 has relatively taller seedling height making it suitable for planting at 20–25 cm stagnant water. Growth duration of this variety is 145 days for mid-July seeding. The yield potential of this variety is 6.5 ton/ha under optimum management. For the MABC scheme, BR11 was crossed as a female with IR40931-33-1-3-2 to obtain F1 seeds. The F1 plant was backcrossed with BR11 to obtain BC1F1 seeds. The whole scheme is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Selection details of the approach in each generation. The numbers of plants selected in each generation is indicated in parentheses.

Molecular marker analysis

DNA was extracted from young leaves of 2-week-old plants using a modified protocol as described by Zheng et al. (1995). PCR was performed in 10 μl reactions containing 25 ng of DNA template following the protocols described by Neeraja et al. (2007). Microsatellite or simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers were used for selection (IRGSP 2005, McCouch et al. 2002, Temnykh et al. 2001). SSR marker alleles were scored and used to produce ‘graphical genotypes’ of the breeding lines using the software program GGT (Van Berloo 2008).

Foreground selection

Initially the robust tightly-linked marker RM8300 was used in the foreground selection. Foreground selection was later confirmed by using intragenic sequence-tagged site (STS) marker Sub1C173 specific to the SUB1C gene and cleaved amplified polymorphic site (CAPS) marker GnS2 specific to the SUB1A gene (Neeraja et al. 2007, Septiningsih et al. 2009, Xu et al. 2006). Individuals that were heterozygous for the foreground markers, which indicated the inheritance of the SUB1 allele from the donor, were selected in this selection step.

RM23679, Sub1C173, RM8300, RM219, RM566, RM242 and RM278 markers were selected from chromosome 9 to monitor the size of the donor segment containing SUB1. GGT was used to analyze the size of the introgression in backcross lines.

Phenotypic selection

From the plants that were selected for SUB1, 10 individuals with the phenotypic appearance close to the recipient parent BR11 were selected visually at vegetative and flowering stages. Phenotypic selection was also carried out over an entire population of BC2F1 generation after foreground selection. The phenotypic parameters considered at vegetative stage included plant height, tillering patterns, number of tillers per hill, leaf size, leaf shape, leaf angle and leaf color. The additional parameters considered at flowering stage included panicle shape, panicle angle to the axis, spikelet shape, spikelet size, spikelet color, flag leaf size, flag leaf shape and flag leaf angle. The 10 selected plants were ranked based on their degree of phenotypic resemblance with BR11 and backcross seeds were produced from the three individuals with highest phenotypic rankings.

In the second backcross generation the same strategy was followed for selection of individual plants with SUB1. In BC2F1 generation, a total of 21 plants, derived from 3 BC1F1 plants, were selected at the vegetative stage and ranked following the same strategy. The 21 selected plants were ranked again at flowering stage and BC3F1 seeds were produced from the individual plant having the highest rank at flowering stage for this approach.

In the BC3F1 generation, foreground and phenotypic selection were again repeated. A total of 10 plants were selected and ranked at flowering stage. BC3F2 seeds were produced from the individual with highest phenotypic rank at flowering stage. Foreground and phenotypic selection were repeated in the BC3F2 generation and a total of 10 plants were selected at flowering stage. The 10 selected plants were allowed to self pollinate and harvested in bulk to produce BC3F3 populations for carrying out selection for promising backcross recombinant lines (BRLs) which were submergence tolerant. The BR11-Sub1 lines were tested so that the newly developed stress tolerant variety could be easily differentiated from original mega variety BR11. A total of 10 plants were again selected in BC3F3 generation and bulked to produce the BC3F4 population. Because there was lot of phenotypic segregation in the bulked BC3F3 population, individual plant selection method was followed in the following generations to obtain homozygous BRLs from this approach. The overall backcross scheme is shown in Fig. 1. The BC4F1 generation was produced for the continuation of the backcrossing scheme and to monitor heterozygosity.

Background selection

Microsatellite markers unlinked to SUB1 covering all the chromosomes including the SUB1 carrier chromosome 9, that were polymorphic between the two parents, were used for background selection to recover the recipient genome. Out of 524 SSR primers surveyed, 77 microsatellite markers including the four flanking markers of the target QTL were used for background selection initially. The microsatellite markers that revealed fixed (homozygous) alleles at non-target loci at one generation were not screened at the next backcross generation. Only those markers that were not fixed for the recurrent parent allele were genotyped in the following generations. The segregants with fixed donor alleles were discarded from the selection in BC1F1, BC2F1 and BC3F1 generations because they indicated accidental selfed plants.

The molecular weights of the different alleles were measured using Alpha Ease Fc 5.0 software. The marker data was analyzed using computer software called Graphical Genotyper (GGT 2.0) (Van Berloo 2008). The homozygous recipient allele, homozygous dominant allele and heterozygous allele were scored as ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘H’, respectively.

Phenotypic rank data was compared to the % recipient parent (RP) genome by using Spearman’s correlation test, which is appropriate for quantitative and ordinal data using SPSS (Version 11, SPSS Inc.). Plants with a high proportion of recipient parent alleles were ranked highest so negative correlations were detected (i.e. a perfect correlation between % RP genome and rank would be −1.0).

Results

Foreground selection

Initially, foreground selection was carried out using the robust tightly-linked marker RM8300. The size of the tolerant allele of this tightly linked marker, which was obtained from the donor of SUB1 (IR40931-33-1-3-2), was 218 bp and that of the susceptible allele obtained from BR11 was 211 bp. Out of 513 BC1F1 plants, 249 plants were found to be heterozygous (Score H), 261 plants were fixed for the recipient allele (susceptible allele) (Score A) and only 3 plants were fixed for the donor allele (tolerant allele) (Score B). The latter three plants with B score were produced due to accidental selfing during of backcrossing. The results fitted the expected 1: 1 ratio of this generation with a non-significant chi square value of 0.28 (P > 0.05). The 249 H plants for the tightly linked marker were subjected to phenotypic selection.

Three BC2F1 populations were produced from crosses with the three plants (nos. 14, 445 and 396), which were the most similar to BR11 and had the highest phenotypic rankings. Out of 311 plants, 166 plants were H and 145 plants were A. The results fitted the expected 1: 1 ratio for this generation (chi-square value 1.42, P > 0.05).

In the BC3F1 generation, foreground selection was carried out over one population produced from BC2F1 plant number 396-18 that had the highest phenotypic ranking at flowering stage. Out of 260 plants, 134 plants were H and 126 plants were A, which indicated that the results fitted the expected 1: 1 ratio of this generation (chi square value 0.250, P > 0.05). The 134 H plants for the tightly linked marker were subjected to phenotypic selection because they carried SUB1. The selected plant of BC3F1 generation was self-pollinated to generate BC3F2 generation for the development of transgressive backcross recombinant lines. In this generation, 89 plants were H, 51 plants A and 42 plants B out of 182 plants. The results fit the expected 1: 2: 1 ratio for this generation (chi-square value of 0.978, P > 0.05). The 42 plants B for the tightly linked marker were subjected to phenotypic selection. It was assumed that those 42 individuals were homozygous for SUB1.

Phenotypic selection and marker-assisted background selection

In the BC1F1 generation, phenotypic selection was carried out for 249 plants that were heterozygous for SUB1. Ten plants (nos. 14, 59, 73, 86, 145, 235, 248, 396, 445 and 496) were selected and ranked based on their phenotypic resemblance to the recurrent parent BR11. The efficiency of phenotypic selection was determined by carrying out background selection over the selected plants using 77 evenly distributed SSR markers. The number of heterozygous alleles and % recipient parent alleles in the phenotypically selected best plant (number 14) was 26 and 82, respectively. The average number of heterozygous alleles over all the 10 phenotypically selected plants was 35. The correlation coefficient between ranking of phenotypic and percent recipient alleles was −0.78 (P < 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of phenotypic and marker-assisted background selection in BC1F1 generation

| Plant No | A | H | B | %R allele | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Phenotypic | |||||

| 59 | 26 | 46 | 0 | 68.1 | 5 |

| 14 | 46 | 26 | 0 | 81.9 | 1 |

| 73 | 23 | 41 | 8 | 60.4 | 8 |

| 145 | 34 | 38 | 0 | 73.6 | 2 |

| 235 | 18 | 43 | 11 | 54.9 | 9 |

| 248 | 26 | 46 | 0 | 68.1 | 7 |

| 86 | 29 | 43 | 0 | 70.1 | 6 |

| 496 | 27 | 45 | 0 | 68.8 | 10 |

| 396 | 48 | 24 | 0 | 83.3 | 4 |

| 445 | 44 | 28 | 0 | 80.6 | 3 |

|

| |||||

| Ave. = 35 | Ave. = 71.0 | Correl.a = −0.78** | |||

P < 0.01

Correlation coefficient between phenotypic ranking and % of recipient alleles.

In the BC2F1 generation, phenotypic selection was carried out over 166 plants of three populations that were heterozygous for SUB1. Seven plants were selected and ranked based on their phenotypic resemblance to BR11 from each population. The efficiency of phenotypic selection was tested using the background markers remaining for the corresponding population. The percentage of recipient alleles was calculated in each of the selected plants considering the markers used in BC1F1 generation also and the selected plants were ranked in ascending order. The highest percentage of recipient alleles was obtained in plants 396-66 and 14–27 (96.1%), followed by plant 14–81 (94.5%). At flowering stage, plant 396-18 obtained the highest phenotypic rank among 21 plants of three populations and the number of heterozygous alleles and % recipient genome in this best plant were 12 and 90.6%, respectively. However, the average number of heterozygous alleles and proportion of recipient alleles from the phenotypically selected plants were 14 and 89%, respectively. Interestingly, plant 14–27 obtained the highest rank both in phenotypic and background selection. The correlation coefficient between rankings of phenotypic selection with the percentage of recipient alleles was –0.075 (not significant) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of phenotypic and marker-assisted background selection in BC2F1 generation

| Population | Plant No. | Rank | %R allele | No. of heterozygous markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Phenotypic | ||||

| 14 | TB1-14-11 | 6 | 93.8 | 8 |

| TB2-14-27 | 1 | 96.1 | 5 | |

| TB3-14-47 | 2 | 91.4 | 11 | |

| TB4-14-72 | 3 | 89.1 | 14 | |

| TB5-14-81 | 7 | 94.5 | 7 | |

| TB6-14-124 | 5 | 89.8 | 13 | |

| TB7-14-104 | 4 | 85.9 | 18 | |

| 396 | TB8-396-2 | 3 | 89.8 | 13 |

| TB9-396-18 | 1 | 90.6 | 12 | |

| TB10-396-26 | 5 | 93.8 | 8 | |

| TB11-396-45 | 2 | 86.7 | 17 | |

| TB12-396-66 | 4 | 96.1 | 5 | |

| TB13-396-89 | 6 | 89.1 | 14 | |

| TB14-396-37 | 7 | 89.8 | 13 | |

| 445 | TB15-445-8 | 6 | 80.5 | 25 |

| TB16-445-18 | 2 | 82.0 | 23 | |

| TB17-445-37 | 5 | 83.6 | 21 | |

| TB18-445-32 | 4 | 93.8 | 8 | |

| TB19-445-48 | 3 | 82.8 | 22 | |

| TB20-445-51 | 1 | 85.2 | 19 | |

| TB21-445-70 | 7 | 88.3 | 15 | |

|

| ||||

| Correl.a = −0.075 | Ave = 89.2 | Ave = 14 | ||

Correlation coefficient between phenotypic ranking and % of recipient alleles.

The efficiency of phenotypic selection was again investigated in an entire and larger BC2F1 population produced from plant number 06 of BC1F1 generation. Out of 49 plants having heterozygous alleles, 24 plants were selected based on phenotypic resemblance to BR11. After that, background selection was carried out over both phenotypically selected (24 plants) and phenotypically non-selected plants (25 plants) using a total of 73 evenly distributed background markers. Total number of homozygous alleles for recipient parent was 148 in the phenotypically selected plants whereas the number was 256 in the phenotypically non-selected plants. There were 10 fixed donor alleles among the phenotypically selected plants.

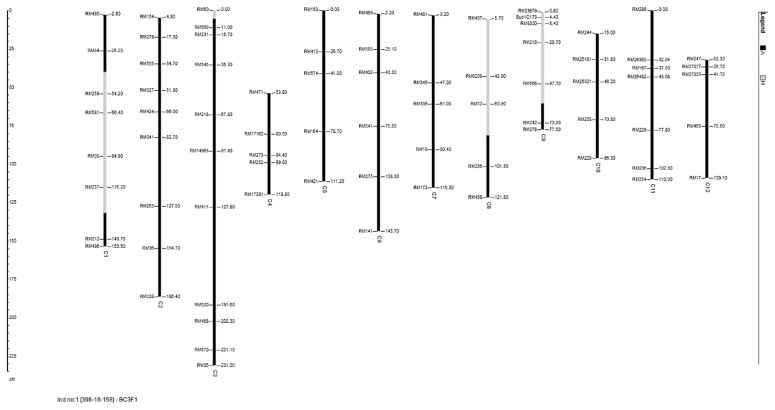

BC3F1 seeds were produced from the plant number 396-18 having the highest rank in the flowering stage in BC2F1 generation. Phenotypic selection was carried out over 134 plants having heterozygous alleles for SUB1 at both vegetative and flowering stage. The efficiency of phenotypic selection was tested by carrying out background selection using 12 background markers remaining for this population over 10 phenotypically selected plants. The highest percentage of recipient alleles was obtained in plant number 396-18-78 (97.9%), followed by plant number 396-18-176 (97.2%) and plant number 396-18-133 (97.2%), respectively (Table 3). The rankings based on phenotypic selection at both stages were compared with the ranking based on background selection. The phenotypically selected best plant at vegetative stage was 396-18-134 and the number of heterozygous alleles and % recipient genome in this plant were 10 and 93, respectively while the best plant at flowering stage was 396-18-158 and the number of heterozygous alleles and % recipient genome in this plant were 9 and 96, respectively. The best plant 396-18-158 was heterozygous for 9 SSR loci on chromosomes 1, 3, 8 and 9 (Fig. 2). The size of the introgressed fragment carrying SUB1 in this plant was around 17 MB (between 14.7 and 18.8 Mb depending on where the breakpoint occurred, http://www.gramene.org). However, the average number of heterozygous alleles and the average percentage of recipient alleles over all the 10 phenotypically selected plants was 6.7 and 95.2%, respectively. The correlation coefficients between the ranking of phenotypic selection at vegetative stage with the ranking of background selection was 0.091 (not significant) and the correlation coefficient between the ranking of phenotypic selection at flowering stage with the ranking of background selection was −0.018 (not significant) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of phenotypic and marker-assisted background selection in BC3F1 generation

| Plant No. | H | A | B | Rank | % R allele | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Vegetative | Flowering | |||||

| 396-18-14 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 91.0 |

| 396-18-71 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 94.4 |

| 396-18-78 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 97.9 |

| 396-18-111 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 95.1 |

| 396-18-133 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 97.2 |

| 396-18-134 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 93.1 |

| 396-18-158 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 96.5 |

| 396-18-176 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 97.2 |

| 396-18-250 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 93.8 |

| 396-18-320 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 95.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Ave = 6.7 | Correl.a = 0.091 | Correl.b = −0.018 | Ave = 95.2 | |||

Correlation coefficient between phenotypic ranking at vegetative stage and % of recipient alleles.

Correlation coefficient between phenotypic ranking at flowering stage and % of recipient alleles.

Fig. 2.

Graphical genotype of the plant 396-18-158 of the BC3F1 generation. The black regions on the chromosomes indicates homozygous region for the recipient genome while the gray colored regions indicates the heterozygous regions. The distances were represented in cM based on published map of Temnykh et al. (2001).

In the BC3F2 generation, phenotypic selection was carried out over 42 positive plants and the efficiency of phenotypic selection was tested by carrying out background selection over 10 phenotypically selected plants using 9 background markers remaining for the population. The highest percentage of recipient alleles was obtained in plant number 396-18-158-1 (97.2%). The phenotypically selected best plant at flowering stage was 396-18-158-22 and the number of heterozygous alleles in this plant was 9 and the percentage of recipient genome was 93.8%. The graphical genotype of this plant was the same as that of phenotypically selected best plant at the BC3F1 generation (Fig. 2). The introgression size of the SUB1 chromosome in this plant was about 17 Mb. However, the average number of heterozygous alleles and the average percentage of recipient alleles over all the 10 phenotypically selected plants was 4.5 and 94.5%, respectively. The correlation coefficient between the ranking of phenotypic selection at flowering stage with the percentage of recipient alleles was −0.087 (not significant) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of phenotypic and marker-assisted background selection in BC3F2 generation

| Plant No. | H | A | B | Phenotypic rank at flowering | % Recipient allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 396-18-158-1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 97.2 |

| 396-18-158-22 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 93.8 |

| 396-18-158-53 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 96.5 |

| 196-18-158-54 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 92.4 |

| 396-18-158-121 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 92.4 |

| 396-18-158-133 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 95.8 |

| 396-18-158-138 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 91.7 |

| 396-18-158-148 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 94.4 |

| 396-18-158-157 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 95.1 |

| 396-18-158-163 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 95.8 |

|

| |||||

| Ave. = 4.5 | Correl.a = −0.087 | Ave = 94.5 | |||

Correlation coefficient between phenotypic ranking at flowering stage and % of recipient alleles.

The seeds of those 10 plants were advanced to the BC3F3 generation where 10 plants were selected based on their phenotypic performance and again bulked. A total of 10 plants having phenotypic parameters similar to BR11 were selected in BC3F4 generation and kept separately to attain homozygosity in the selected backcross recombinant segregants.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated alternative backcrossing strategies for introgressing a major QTL (SUB1) using a combination of foreground and phenotypic selection or foreground selection and marker-assisted background selection. In foreground selection of different generations, the genotypic classes fit the expected chi-square ratios for single gene inheritance. The significant correlation coefficient (−0.78**) among the rankings of phenotypic and background selection indicated accuracy of phenotypic selection compared with background selection in the BC1F1 generation. The high efficiency of phenotypic selection in BC1F1 generation might be due to highest phenotypic variation among the segregants in this generation. These results suggested that visual phenotypic selection in BC1F1 was effective compared to selection with markers in this generation and background selection could be avoided in this generation to minimize the genotyping cost.

The correlations between the rankings of phenotypic selection and background selection were all non-significant in BC2F1, BC3F1 and BC3F2 generations. The magnitude of correlation indicated that phenotypic selection was not accurate compared with background selection in these later generations. This may be explained by decreasing phenotypic variation among the segregants in the advanced generations, which made phenotypic selection difficult. However this result must be carefully interpreted due to the very small sample size. There was no considerable advantage of phenotypic selection at flowering stage compared to selection at vegetative stage also. Nine segregating loci present in the phenotypically selected best plant of BC3F1 generation suggested that the appropriate generation of selfing in backcross breeding using phenotypic selection would be BC5F1. The number of segregating loci was 24 and 12 in the BC1F1 and BC2F1 generations. Based on expected segregation ratios, the minimum number of heterozygous markers in the best plants could be considered as four to self pollinate for generating a population which would be economically manageable for genotyping. Although the number of backcrosses required was similar to conventional breeding, the strategy would be effective in introgressing a QTL particularly for the resource poor countries that lack high through-put genotyping facilities.

Phenotypic selection was also carried out over a higher number of positive individuals in a population of the BC2F1 generation. The results also clearly exhibited the failure of phenotypic selection with respect to recovery of the recipient parent genome. Moreover, a number of phenotypically selected plants had fixed donor alleles. As the segregants with homozygous alleles for donor parent in their background were completely undesirable in the MABC scheme, these kinds of segregants selected through phenotypic selection showed the limitation of phenotypic selection with respect to accurate recovery of the recurrent parent genome.

The introgression size in the phenotypically selected best plant of BC3F1 and BC3F2 was around 60 cM or 17 Mb. The phenotypically selected best plants of BC1F1 and BC2F1 generations also had the same amount of heterozygous chromosomal segments on the carrier chromosome. The huge introgression size was due to not carrying out recombinant selection for reducing linkage drag. This 17-Mb portion of donor chromosome could contain approximately 1500 genes (IRGSP 2005). Ribaut and Hoisington (1998) reported that using conventional breeding methods, the donor segment could remain very large even with many backcross generations (e.g., >10). Again, the introgression size in conventional breeding had been reported to be 50 cM or more (Salina et al. 2003, Young and Tanksley 1989). As the donor parent often possesses many undesirable agronomic traits, the inheritance of such a large donor segment indicated the weakness of conventional backcross breeding with respect to minimizing linkage drag. However, by using an improved donor, this problem could be partially overcome. Young and Tanksley (1989) reported that incorporation of a resistance gene was difficult with conventional breeding methods because of linkage with undesirable traits that was very difficult to break even with many generations of backcrosses. Recombinant selection—the process of selecting individuals with recombination events between the target locus and tightly-linked flanking markers—can be used to minimize linkage drag (Collard and Mackill 2008).

In conclusion, the findings of the present study clearly reflect the reduced accuracy of phenotypic selection compared to background selection using markers, particularly after the BC1F1 generation. However, an alternative strategy to postpone marker-assisted background selection until BC2F1 could save considerable resources.

Acknowledgements

Technical assistance from J. Mendoza, E. Suiton, N. Ramos, G. Perez and S. Ali is gratefully acknowledged. The author is thankful to BRRI and IRRI authorities for providing support in this research. The work was also supported in part by a grant from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

Literature Cited

- Collard B.C.Y., Mackill D.J. (2008) Marker-assisted selection: an approach for precision plant breeding in the 21st century. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. B Rev. 363: 557–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital F., Charcosset A. (1997) Marker-assisted introgression of quantitative trait loci. Genetics 147: 1469–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iftekharuddaula K.M., Newaz M.A., Salam M.A., Ahmed H.U., Mahbub M.A.A., Septiningsih E.M., Collard B.C.Y., Sanchez D.L., Pamplona A.M., Mackill D.J. (2011) Rapid and high-precision marker assisted backcrossing to introgress the SUB1 QTL into BR11, the rainfed lowland rice mega variety of Bangladesh. Euphytica 178: 83–97 [Google Scholar]

- IRGSP (2005) The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436: 793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackill D.J., Amante M.M., Vergara B.S., Sarkarung S. (1993) Improved semidwarf rice lines with tolerance to submergence of seedlings. Crop Sci. 33: 749–753 [Google Scholar]

- McCouch S.R., Teytelman L, Xu Y, Lobos K.B., Clare K, Walton M, Fu B., Maghirang R., Li Z., Zing Y., et al. (2002) Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.). DNA Res. 9: 199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeraja C.N., Maghirang-Rodriguez R, Pamplona A, Heuer S, Collard B.C.Y., Septiningsih E.M., Vergara G, Sanchez D, Xu K, Ismail A.M., et al. (2007) A marker-assisted backcross approach for developing submergence-tolerant rice cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 115: 767–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaut J.M., Hoisington D. (1998) Marker-assisted selection: new tools and strategies. Trends Plant Sci. 3: 236–239 [Google Scholar]

- Salina E., Dobrovolskaya O, Efremova T, Leonova I, Roder M.S. (2003) Microsatellite monitoring of recombination around the Vrn-B1 locus of wheat during early backcross breeding. Plant Breed. 122: 116–119 [Google Scholar]

- Septiningsih E.M., Pamplona A.M., Sanchez D.L., Neeraja C.N., Vergara G.V., Heuer S, Ismail A.M., Mackill D.J. (2009) Development of submergence tolerant rice cultivars: The Sub1 locus and beyond. Ann. Bot. 103: 151–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temnykh S., DeClerck G., Lukashova A., Lipovich L., Cartinhour S., McCouch S. (2001) Computational and experimental analysis of microsatellites in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Frequency, length variation, transposon associations, and genetic marker potential. Genome Res. 11: 1441–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berloo Van R. (2008) GGT 2.0: Versatile software for visualization and analysis of genetic data. J. Hered. 99: 232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Mackill D.J. (1996) A major locus for submergence tolerance mapped on rice chromosome 9. Mol. Breed. 2: 219–224 [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Xia X., Fukao T., Canlas P., Maghirang-Rodriguez R., Heuer S., Ismail A.M., Bailey-Serres J., Ronald P.C., Mackill D.J. (2006) Sub1A is an ethylene response factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature 442: 705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young N.D., Tanksley S.D. (1989) RFLP analysis of the size of chromosomal segments retained around the tm-2 locus of tomato during backcross breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 77: 353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng K., Subudhi P.K., Domingo J, Magpantay G, Huang N. (1995) Rapid DNA isolation for marker assisted selection in rice breeding. Rice Genet. Newsl. 12: 255–258 [Google Scholar]