Abstract

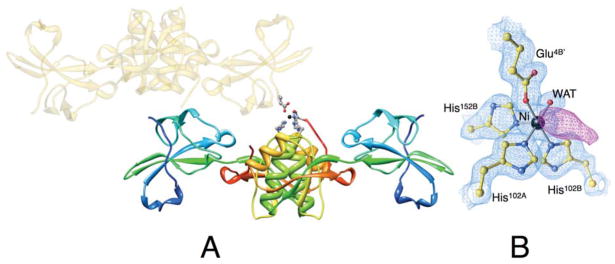

The survival and growth of the pathogen Helicobacter pylori in the gastric acidic environment is ensured by the activity of urease, an enzyme containing two essential Ni2+ ions in the active site. The metallo-chaperone UreE facilitates in vivo Ni2+ insertion into the apo-enzyme. Crystals of apo-HpUreE and its Ni2+ and Zn2+ bound forms were obtained from protein solutions in the absence and presence of the metal ions. The crystal structures of the homodimeric protein, determined at 2.00 Å (apo), 1.59 Å (Ni) and 2.52 Å (Zn) resolution, show the conserved proximal and solvent-exposed His102 residues from two adjacent monomers invariably involved in metal binding. The C-terminal regions of the apo-protein are disordered in the crystal, but acquire significant ordering in the presence of the metal ions due to the binding of His152. The analysis of X-ray absorption spectral data obtained on solutions of Ni2+- and Zn2+-HpUreE provided accurate information of the metal ion environment in the absence of solid-state effects. These results reveal the role of the histidine residues at the protein C-terminus in metal ion binding, and the mutual influence of protein framework and metal ion stereo-electronic properties in establishing coordination number and geometry leading to metal selectivity.

Keywords: Urease assembly, metal trafficking, metal ion selectivity, metallochaperone, protein crystallography, X-ray absorption spectroscopy

INTRODUCTION

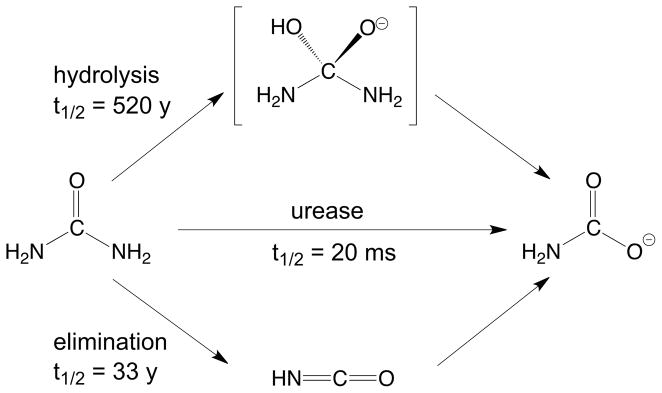

Urease [1, 2] is a nickel-dependent enzyme that plays a crucial role in the nitrogen cycle by catalyzing the hydrolysis of urea to ammonia and carbamate with a 3×1015 fold rate enhancement with respect to the uncatalyzed reaction [3] (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

The active site contains two Ni2+ ions that are bridged by a post-translationally carbamylated lysine residue and a hydroxide ion, and are bound to the protein framework by four histidine imidazole nitrogen atoms and one aspartate residue carboxylate oxygen atom [4–7]. The coordination geometry of the nickel ions is completed by labile water molecules, yielding one penta-coordinated Ni2+ ion with a distorted square-pyramidal geometry, and one hexa-coordinated Ni2+ ion with a distorted octahedral geometry (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Urease is initially produced in the apo-form, devoid of nickel ions and enzymatic activity. The apo-enzyme is modified in several successive steps that require a dedicated set of accessory proteins, usually comprising UreD, UreF, UreG and UreE. [8] This process leads to carbamylation of the active site lysine and incorporation of the binuclear metallic active site, with consequent enzyme activation (Scheme 2). The activity of urease is strictly required for the survival and growth of bacterial pathogens that colonize human and animal gastric mucosa as well as intestinal and urinary tracts, and therefore both the enzyme and the accessory proteins represent targets for drug development.[9, 10]

The urease activation process entails the formation of a multimeric complex between the apo-enzyme and UreD, UreF, and UreG, with the latter protein being likely responsible for lysine carbamylation following GTP hydrolysis. UreE appears to act as a metallo-chaperone by delivering Ni2+ to the UreDFG complex.[11–13] This role for UreE is supported by the evidence that the concentration of Ni2+ required for proper assembly of the urease active site is considerably reduced, and a larger amount of enzyme is activated, in the presence of UreE.[14] Another crucial role for UreE is the enhancement of the GTPase activity of UreG,[13] which relies on the direct UreE-UreG interaction recently shown to occur in vivo and in vitro.[15, 16]

Recombinant UreE proteins from different sources, including Klebsiella aerogenes (KaUreE),[17] Bacillus pasteurii (BpUreE),[18] and Helicobacter pylori (HpUreE),[19] have been structurally characterized. These orthologues consistently exhibit a homo-dimeric architecture made of an N-terminal domain and a C-terminal domain, the latter mediating head-to-head dimerization. A conserved metal binding site involves a pair of closely spaced histidine residues, one per each monomer, located on the protein surface at the homodimer interface (His96 in KaUreE, His100 in BpUreE, and His102 in HpUreE).

Despite sharing common structural features, UreE proteins have different metal binding capabilities. In particular, they exhibit a variable stoichiometry for nickel binding, that ranges from one metal ion bound per dimer for HpUreE,[15, 20] to six ions for KaUreE,[21] with two Ni2+ bound in case of BpUreE.[22] Interestingly, this peculiarity is reflected by the nature of their C-terminal regions. KaUreE, possessing the highest nickel sequestering activity, features a His-rich tail containing ten histidine residues among the last fifteen amino acids. BpUreE displays two C-terminal histidine residues at the end of its sequence, in the context of a His-Gln-His motif, while in this region HpUreE contains a single histidine residue (His152).[23]

All UreE proteins contain at least one histidine residue in the C-terminal portion, an observation that suggested a role for the C-terminus in modulating the metal trafficking activity of UreE proteins, in terms of both selectivity and stoichiometry of metal binding.[15, 22, 23] However, the structural and functional details of these regions are not well established. The crystal structure of KaUreE was determined on a truncated form of this protein (H144*KaUreE) that lacks the last fifteen residues,[17] while the crystal structure of BpUreE showed solid state disorder that prevented the observation of the Gly-His-Gln-His motif at the C-terminus.[18] The recently described structures of HpUreE in the apo-form or bound to Cu2+, to Ni2+, or to an unidentified metal ion, cover only residues 1/2 – 148/149, and therefore do not include His152. The only exception is the tetrameric (dimer of dimers) form of Ni-HpUreE, which features a square pyramidal nickel site comprised of four His102 (one from each protomer) in the basal plane and a single His152 in the axial position.[19] However, this type of tetrameric arrangement, even though observed commonly in the solid state probably because of the elevated concentrations utilized for protein crystallization, does not correspond to the simple dimeric form of the protein present in solution, as established using static and dynamic light scattering.[15, 22]

The present work describes the crystal structures of recombinant HpUreE in the apo-, Ni2+-bound, and Zn2+-bound forms. These structures reveal the architecture of the C-terminal arm and the metal-binding mode of the His152 residue located in this region. The structures, determined in the solid state, were corroborated by X-ray absorption spectroscopy in frozen solutions of the wild type and the H152A HpUreE mutant proteins in the presence of bound Ni2+ and Zn2+, providing accurate metric parameters in the vicinity of the metal ions. The results presented here clarify the role of the protein framework for Ni2+ and Zn2+ trafficking effected by UreE within the urease activation process.

EXPERIMENTAL

Protein crystallization

Recombinant apo-HpUreE was purified as previously described.[15] Crystallization trials were carried out using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals of the apo-protein were obtained by mixing 2 μL of a 8 mg/mL protein solution in TrisHCl buffer, pH 7, with a reservoir solution containing 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.6, 0.5 M ammonium sulfate, and 1.0 M lithium sulfate. Cuboidal crystals appeared within two weeks. Crystals of Zn-HpUreE were obtained by mixing 2 μL of a 8 mg/mL protein solution in TrisHCl buffer, pH 7, containing an equimolar amount of Zn2+ (ZnSO4), with 2 μL of a reservoir solution made of 4.0 M sodium formate and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5. Crystals with an hexagonal cross section formed within two weeks. Crystals of Ni-HpUreE were obtained by mixing 2 μL of a 8 mg/mL protein solution in TrisHCl buffer, pH 7, containing an equimolar amount of Ni2+ (NiSO4), with 2 μL of a reservoir solution made of 4.0 M sodium formate and 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5. One block-shaped crystal appeared after ca. 30 days.

X-ray diffraction data collection, structure determination and refinement

X-ray diffraction data were recorded on the BL14.1 and BL14.2 beam lines at BESSY (Berlin), at 100 K in the presence of 20% of glycerol or 4.0 M sodium formate as a cryo-protectant. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

X-ray diffraction data collection and refinement statistics

| Zn-HpUreE | Ni-HpUreE | Apo-HpUreE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Beamline | BESSY BL14.2 | BESSY BL14.2 | BESSY BL14.1 | ||

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Peak | Inflection | Remote | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.28183 | 1.28316 | 1.27655 | 0.91885 | 0.91841 |

| Space group | P6522 | C2221 | P212121 | ||

| Cell Constants (Å) | |||||

| a | 109.34 | 67.55 | 69.00 | ||

| b | 109.34 | 117.14 | 70.47 | ||

| c | 280.34 | 98.66 | 123.34 | ||

| Resolution (Å)(a) | 50.00 - 2.52 (2.56 - 2.52) | 50.00 - 2.59 (2.63 - 2.59) | 50.00 - 2.77 (2.82 - 2.77) | 50.00 - 1.59 (1.62 - 1.59) | 20.00 – 2.00 (2.03 – 2.00) |

| Rsym(a) | 0.092 (0.434) | 0.095 (0.586) | 0.100 (0.558) | 0.049 (0.448) | 0.060 (0.593) |

| I/σ(I)(a) | 22.4 (3.4) | 21.5 (2.3) | 20.8 (2.3) | 24.9 (2.6) | 21.6 (2.0) |

| Completeness (%)(a) | 99.9 (98.2) | 99.7 (95.9) | 99.5 (92.9) | 97.9 (87.7) | 99.7 (96.6) |

| Redundancy(a) | 9.4 (6.9) | 9.1 (5.2) | 9.0 (4.9) | 8.4 (3.2) | 5.5 (4.9) |

|

| |||||

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.52 | 1.59 | 2.00 | ||

| No. of reflections | 33219 | 48955 | 38745 | ||

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.203/0.245 | 0.185/0.210 | 0.208/0.267 | ||

| Number of protein atoms | 4697 | 2402 | 4734 | ||

| Number of metal atoms | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Number of water molecules | 186 | 154 | 100 | ||

| Average B-factor for protein atoms (Å2) | 43.815 | 33.694 | 44.327 | ||

| Average B-factor for metal atoms (Å2) | 37.275 | 28.650 | - | ||

| Root mean square deviations of bond lengths (Å) | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.022 | ||

| Root mean square deviations of bond angles (°) | 1.909 | 2.578 | 1.947 | ||

| PDB code | 3TJ9 | 3TJ8 | 3TJA | ||

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Three data sets for the Zn-HpUreE crystal were collected in a MAD experiment in the 2.52–2.77 Å resolution range. The images were processed with the HKL package[24] using an ‘anomalous’ option during scaling. The Zn-HpUreE structure was solved with a three-wavelength MAD protocol in Auto-Rickshaw.[25] Heavy atom search was performed with SHELXD,[26] and the resulting positions were refined with phase calculation using SHARP.[27] The density modification and phase extension were done using DM[28] and RESOLVE.[29] An initial model was built using ARP/warp.[30, 31] Heavy atom analysis based on the initial model, together with phasing and building cycles, were performed using PHASER,[32] MLPHARE,[33] SHELXE,[34] RESOLVE,[29] and BUCCANEER.[33] Three heavy atom sites were detected, which included two zinc ions and the sulfur atom of Cys95. Initially, 598 residues from the four protomers in the asymmetric unit were found by automatic modeling, followed by manual model building and refinement using REFMAC [35].

One data set at 1.59 Å resolution was recorded for the Ni-HpUreE crystal. The data were processed with the HKL package.[24] The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER[32] with one chain of Zn-HpUreE as the search model. Solutions were found that corresponded to two HpUreE protomers in the asymmetric unit. The atomic model was refined using REFMAC.[35]

One data set at 2.00-Å resolution was recorded for apo-HpUreE crystal. The data were processed with the HKL package.[24] The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER,[32] with one chain of Ni-HpUreE as the search model. Four apo-HpUreE protomers were found in the asymmetric unit. The atomic model was refined using REFMAC.[35]

X-ray absorption spectroscopy sample preparation

Metal ions (0.9 equivalents) as sulfate salts were added to stock solutions of wild type HpUreE dimer (0.60 mM) and H152A-HpUreE dimer (0.25 mM for zinc and 0.87 mM for nickel) to prepare Zn2+ and Ni2+ bound protein samples. Final sample concentrations are listed in Table 2. Samples were prepared in 20 mM TrisHBr buffer at pH 7, containing 150 mM NaBr. The protein samples were incubated for five minutes upon metal addition, loaded into sample cells consisting of a polycarbonate sample holder with a kapton window, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at −80 °C and transported in liquid nitrogen before being used at the synchrotron beam line. Based on established Kd values and protein concentrations,[15] less than 2% of the Ni2+ and Zn2+ added should be dissociated under these conditions.

Table 2.

Final sample concentrations used for EXAFS analysis of HpUreE wild type and H152A mutant

| Sample | Protein (mM) | Ni2+ (mM) | Zn2+ (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HpUreE Ni | 0.53 | 0.48 | |

| HpUreE Zn | 0.53 | 0.48 | |

| H152A HpUreE Zn | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| H152A HpUreE Ni | 0.77 | 0.69 |

X-ray absorption spectroscopy data collection and analysis

Datasets were collected at SSRL (Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, 3 GeV ring) beam line 9-3 equipped with a 100-element Ge X-ray fluorescence detector array (Canberra). The only exception is the H152A HpUreE nickel sample, which was run at beam line 7-3 using a 30-element Ge-detector. Both stations consisted of a Si(220) φ = 0° double crystal monochromator, and a liquid helium cryostat for the sample chamber. Söller slits were used to reduce scattering and 3 μm Z-1 element filters were placed between the sample and the detector. Internal energy calibration was performed by collecting spectra simultaneously in transition mode on the relevant metal foil (Zn or Ni).

Data averaging and energy calibration was performed using SixPack.[36] The first inflection points from the XANES spectral regions were set to 9660.7 eV for Zn foil (Zn samples) and to 8331.6 eV for Ni foil (Ni samples). The AUTOBK algorithm available in the Athena software package was employed for data reduction and normalization.[37] A linear pre-edge function followed by a quadratic polynomial for the post-edge was used for background subtraction followed by normalization of the edge-jump.

Data limits were chosen to maximize resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. The Zn-HpUreE EXAFS data was extracted using an Rbkg of 0.9 and a spline with a range of k = 2 to 13.5 Å−1 having a rigid spline clamp at higher k. The k3-weighted data was fit in r-space over the k = 2 – 13.5 Å−1 range using an E0 of 9670 eV. The Ni-HpUreE EXAFS data was extracted using an Rbkg of 1, and a spline from k = 2 to 13.5 Å−1 with a strong clamp at high k-values for wild type HpUreE, and a spline from k = 2 to 12.5 Å−1 with a rigid clamp at higher k values for H152A HpUreE. The k3-weighted data was fit in r-space over the k = 2 – 13.5 Å−1 region for wild type HpUreE, and k = 2 – 12.5 Å−1 for the mutant, with E0 for Ni set to 8340 eV in both cases. All data sets were processed using a Kaiser-Bessel window with a dk = 2 (window sill).

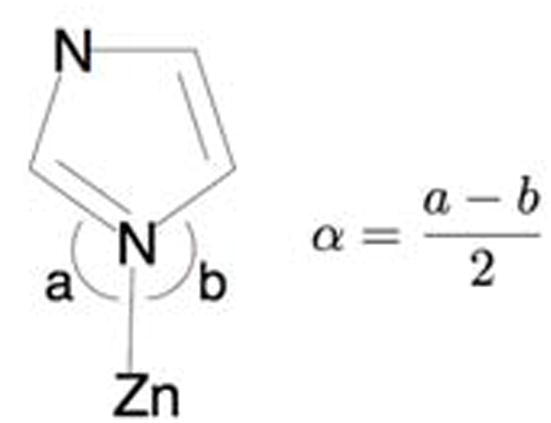

Artemis employing the FEFF6 and IFEFFIT algorithms was used to generate and fit scattering paths to the data.[37–39] Single-scattering and multiple-scattering fits were performed as described in subsequent sections. Single-scattering fits were generally carried out over an r-space of 1 – 2.0 (and up to 2.5) Å, while multiple-scattering fits were generated over the 1 – 4.0 (and up to 4.2) Å range of r-space, as specified in the Supplementary Information. Average values and bond lengths obtained from crystallographic data were used to construct rigid imidazole rings to fit histidine residues.[40] The position of the imidazole ring with respect to the metal center was fit in terms of the metal-ligand bond distance (Reff) and the rotation angle α (Scheme 3).[41, 42]

Scheme 3.

To assess the goodness of fit from different fitting models, the R-factor, χ2, and reduced χ2 (χν2) were minimized. Increasing the number of adjustable parameters is generally expected to improve the R-factor; however χν2 may go through a minimum then increase indicating that the model is over-fitting the data. These parameters are defined as follows:

and:

where Nidp is the number of independent data points defined as:

Δr is the fitting range in r-space, Δk is the fitting range in k-space, Npts is the number of points in the fitting range, Nvar is the number of variables floating during the fit, ε is the measurement uncertainty, Re() is the real part of the EXAFS Fourier-transformed data and theory functions, Im() is the imaginary part of the EXAFS Fourier-transformed data and theory functions, χ(Ri) is the Fourier-transformed data or theory function, and

RESULTS

X-ray crystallography on HpUreE in the apo and holo forms bound to Ni2+ and Zn2+

Three crystal structures have been analyzed: HpUreE in the apo form at 2.00 Å resolution (apo-HpUreE), the protein co-crystallized with Ni2+ at 1.59 Å resolution (Ni-HpUreE), and the protein co-crystallized with Zn2+, solved at 2.52 Å (Zn-HpUreE). Each structure is in a different crystal form.

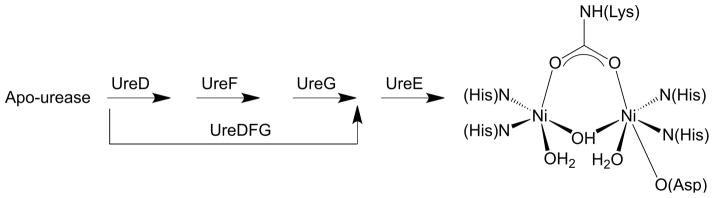

The crystals of the apo-protein are orthorhombic, P212121, with four polypeptide chains assembled into two dimers in the asymmetric unit (Figure 1). Each chain was modeled starting from the N-terminal Met, but at the C-termini the last 20–22 residues are disordered and therefore invisible. Unambiguous electron density in chain A extends to Ser149, to Met150 in chains B and D, and to Val148 in chain C.

Figure 1.

Ribbon schemes of the crystallographic structural model of apo-HpUreE dimer of dimers in the asymmetric unit. Panel B represents the same structure of panel A rotated by 90° about the horizontal axis. Each of the protomers forming the dimer on the left is colored from blue in the proximity of the N-terminal to red at the C-terminus in order to highlight the secondary structure elements along the protein sequence. The dimer on the right shows the two protomers in different colors. The side chains of the conserved His102 are represented as ball-and-stick models colored according to the CPK color code.

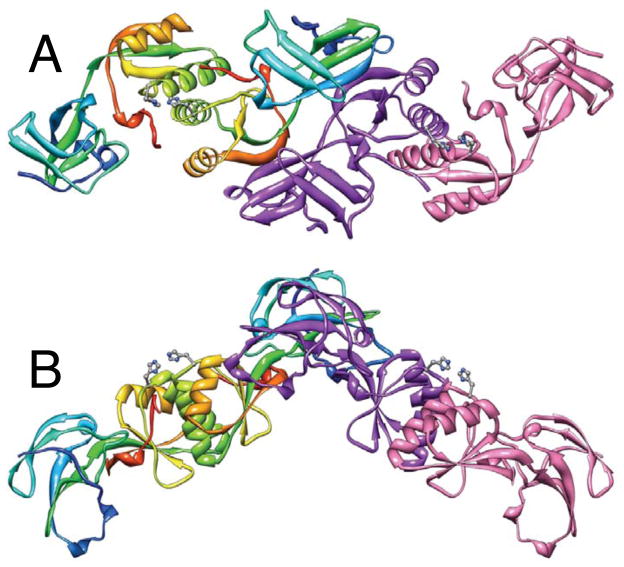

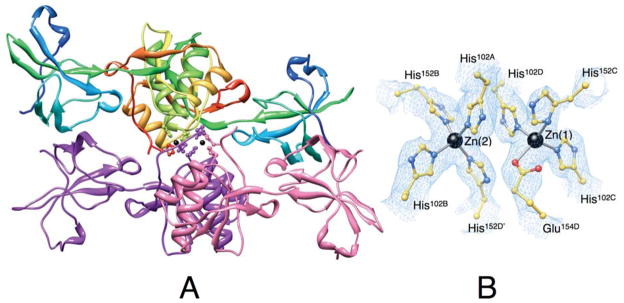

The Ni-HpUreE crystals are orthorhombic, C2221, with one protein dimer and one Ni2+ ion in the asymmetric unit (Figure 2). Amino acid residues were modeled from Met1 to His149 for chain A and from Met1 to His152 for chain B.

Figure 2.

(A) Ribbon scheme of the crystallographic structural model of Ni-HpUreE dimer in the asymmetric unit, with each protomer colored from blue in the proximity of the N-terminal to red at the C-terminus in order to highlight the secondary structure elements along the protein sequence. The symmetry-related dimer that carries the Glu4B′ residue bound to nickel (represented as a black sphere) is shown as transparent gold ribbon. The side chains of the Ni-bound ligands His102A, His102B, His152B, Glu4B′, as well as the solvent molecule, are represented as ball-and-stick models colored according to the CPK color code. Panel B shows a close-up of the coordination environment of the Ni2+ ion together with the 2Fo−Fc electron density map contoured at 1.5 σ (light blue) and the Fo−Fc electron density map contoured at 3.0 σ (violet).

The Zn-HpUreE crystals are hexagonal, P6522, and contain two protein dimers and two Zn2+ ions in the asymmetric unit (Figure 3). The polypeptide chains were modeled from the N-terminal Met1. Chains B and C could be traced to residue Ser153 and Glu154, respectively. Chains A and D were modeled to Ser149, while the electron density from residue 150 to 154 is unclear and has been interpreted as statically disordered residues (see below). In addition, the electron density in chain D is disordered from Leu13 to Ser19 and from Lys65 to Ile71.

Figure 3.

Ribbon scheme of the crystallographic structural model of Zn-HpUreE dimer of dimers in the asymmetric unit. Each protomer of the dimer on the top is colored from blue in the proximity of the N-terminal to red at the C-terminus in order to highlight the secondary structure elements along the protein sequence. The dimer on the bottom shows the two protomers in different colors. The side chains of the histidine residues binding the Zn2+-ions (shown as black spheres) are represented as ball-and-stick models colored according to their position in the sequence and in the protomer. Panel B shows a close-up of the coordination environment of the Zn2+ ions together with the 2Fo−Fc electron density map contoured at 1.0 σ (light blue).

The polypeptide fold is similar to the previously reported crystal structures of KaUreE,[17] BpUreE,[18] and HpUreE.[19] Each protein subunit contains two domains (Figures 1–3). The N-terminal domain includes residues from Met1 to Asp77 and consists of two three-stranded mixed β-sheets with two extended loops connecting strands 1 with 2, and strand 2 with 3. Each of the two loops contains a β-turn. The C-terminal domain includes residues from Ser78 and has a ferredoxin-like β αββαβ fold. Residues Glu144 to Leu146 form a short fifth β-strand and the last ordered residues stretch along the two α-helices of the other subunit of the dimer. The segment from Ser149 to Glu154 is poorly ordered but interpretable in Zn-HpUreE, whereas the remaining residues, up to the C-terminal Lys170, are not visible in the electron density.

The proteins in the three crystal structures form dimers. The core of their interface is formed by two α-helices (residues 88–102) running in parallel. Each helix is braced on the other side by a segment of residues 146–150 from the other subunit. Both hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonded interactions occur between the two helices and between the helices and neighboring residues, and the poorly ordered C-terminal stretch, with a notable hydrophobic cluster formed by pairs of Val88 and Val91 from the two subunits. Symmetric inter-subunit hydrogen bonds are found between Tyr96 and Ala103, Asn100 and His102, Ala89 and Gln111, and between Glu97 and Ser149.

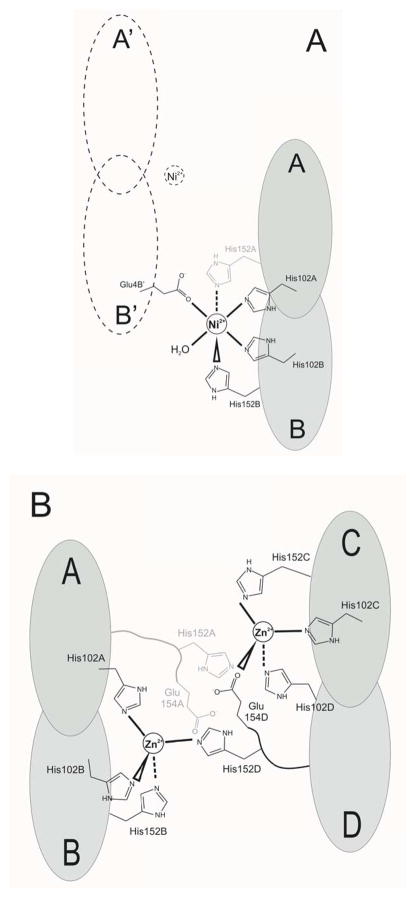

The Ni2+ ion in Ni-HpUreE coordinates six ligands arranged in a pseudo-octahedral coordination geometry (Figure 2). It interacts with His102A, His102B, His152B, Glu4B′ (a residue located on chain B of a symmetry-related molecule), one water molecule, and another unidentified ligand (Figure 4A). The electron density of this moiety is elongated, and therefore it is unlikely to be a water molecule (Figure 2B). It could be His152A, but there is no continuity in the electron density between this ligand density and the nearby Ser149A, which is the last visible residue of chain A. This implies a disordered chain comprising residues 150 and 151. The role of Glu4B′ in forming a dimer of dimers is likely a solid state effect since only dimers (not tetramers) are observed in solution using multi-angle scattering, [15, 22] and this dangling nickel ligand could easily be replaced by a water in solution.

Figure 4.

(A) Scheme of the Ni2+ interaction with six ligands in the Ni-HpUreE structure. The A/B dimer is shown in gray, and the symmetry related dimer A′/B′ is shown with a dashed line. The ambiguous interaction with His154A is drawn with a gray line. (B) Scheme of the two Zn2+ ions interactions with four ligands each, in the Zn-HpUreE structure. Dimers A/B and C/D are shown in gray. The alternative interactions with His152A and Glu154A are shown using a gray line.

In Zn-HpUreE each of the two Zn2+ ions have four ligands arranged in a pseudo-tetrahedral coordination geometry (Figure 3B). Zn(1) interacts with His102C, His102D, His152C and a partially disordered Glu154D, while Zn(2) is bound by His102A, His102B, His152B and the partially disordered His152D from the neighboring C/D dimer (Figure 4B). The electron density corresponding to the segment His152D to Glu154D suggests an alternative interpretation, with the side chain of His152A taking the place of Glu154D, and Glu154A replacing His152D. The first alternative seems to have a higher occupancy factor but some residual density indicates that the second alternative also occurs in the crystal.

All the subunits of the apo and metal-bound HpUreE models were superposed using the Cα atoms. The root-mean-square deviations (rmsd) ranged 0.6–1.1 Å. The number of outliers, pairs of atoms deviating more than 3 rmsd, ranged 0–9. A comparison with the previously determined structures of UreE from H. pylori (PDB codes 3MY0 and 3L9Z) gave similar statistics. Comparing the two apo-HpUreE dimers or the two Zn2+ dimers present in the asymmetric unit gave a similarly good fit (0.8–0.9 Å, with 0 and 3 outliers, respectively). Significantly larger differences were observed only when apo-HpUreE dimers were compared with metal-loaded dimers (rmsd 1.3–1.4 Å with 30–66 outliers) and when Zn2+-bound dimers were compared with Ni2+-bound dimers (rmsd 0.9 Å with 48 outliers), with the largest differences observed in the outer (C-terminal) domains of the dimer.

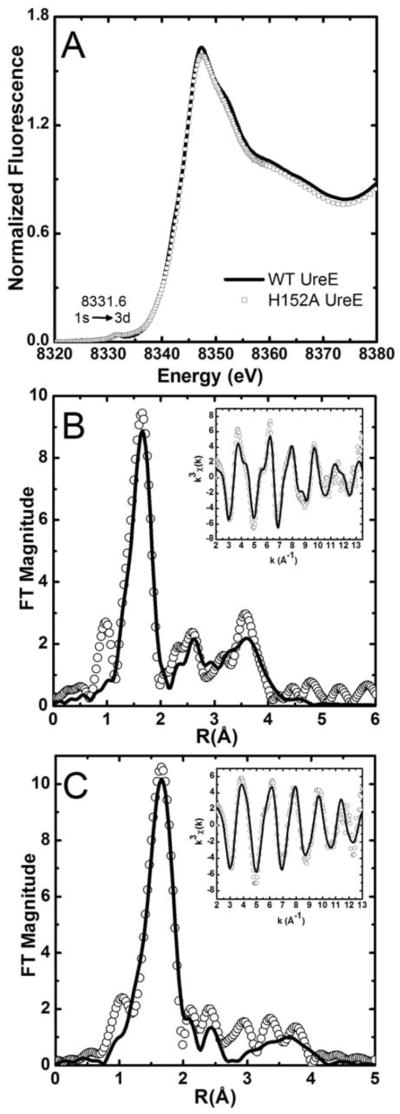

X-ray absorption spectroscopy on the Ni-binding site in wild type and H152A HpUreE

The Ni K-edge XANES spectra of both the wild type and H152A mutant Ni-HpUreE samples exhibit a single intense white line at ~8347 eV, and a small pre-edge peak that is associated with a 1s → 3d transition at 8331.6 eV, consistent with a six-coordinate nickel binding site and octahedral geometry (Figure 5A).[43] The difference between the spectra obtained for wild type and the mutant HpUreE samples arises from the nature of the ligands involved, as revealed by the analysis of the EXAFS spectra (Tables SI-1, SI-2, SI-3, SI-4 in Supplementary Information).

Figure 5.

(A) Ni K-edge XANES spectra of wild type and H152A Ni-HpUreE. (B) Fourier-transformed Ni K-edge EXAFS spectra of wild type Ni-HpUreE (no phase correction, FT window = 2–13.5 Å−1). The inset shows the k3-weighted unfiltered EXAFS spectra: data (black line), best fit (white circles). (C) Fourier transformed Ni K-edge EXAFS spectra of H152A Ni-HpUreE (no phase correction, FT window = 2–12.5 Å−1). The inset shows the k3-weighted unfiltered EXAFS spectra: data (black line), best fit (white circles).

The best multiple-scattering fits of the wild type Ni-HpUreE (Tables SI-1 and SI-2) are consistent with the presence of four histidine residues around the Ni2+ center, spread over two shells of N/O-donor ligands (Figure 5B). The features between 2 to 4 Å are best described using a combination of histidine ligands with an angle α of 5° and 10°, separated in two scattering shells. At 2.06(2) Å, a shell is formed by a pair of histidine residues with an angle α of 10° and two N/O ligands. The second shell consists of an additional two histidine residues (α = 5°) at 2.15(1) Å (Table 3, Figure 5B, Table SI-2). The separation between the two shells of ~0.09(3) Å is at the limit of the resolution (~0.1 Å) for the data set. Splitting the histidine residues into two shells significantly improves the goodness of fit, although the reduced χ2 only drops by a factor of 1.3 (vs. an optimal factor of 1.7). Such a two-shell model is consistent with the wild type HpUreE nickel binding site described by the crystallographic data presented in this work, as well as theoretical models.[15] Both studies show the presence of two distinct sets of histidine residues at the nickel site in the wild type HpUreE dimer, the His102 pair and the His152 pair, where the His102 pair is essential for metal binding.

Table 3.

Best fit EXAFS models

| Sample | Ligand(a) | r (Å) | σ2 (×103 Å2) | %R | χν2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT Ni-HpUreE | 2 NHis10 | 2.15(2) | 3(1) | 3.8 | 36.6 |

| 2 NHis5 | 2.06(1) | 2.5(7) | |||

| 2 N/O | 2.06(1) | 2.5(7) | |||

| H152A Ni-HpUreE | 2 NHis10 | 2.09(1) | 3.7(5) | 5.2 | 32.4 |

| 4 N/O | 2.09(1) | 3.7(5) | |||

| WT Zn-HpUreE | 2 NHis5 | 1.99(2) | 5(1) | 3.78 | 17.3 |

| 2 N/O | 2.07(3) | 12(5) | |||

| 1 Br | 2.38(1) | 4.3(4) | |||

| 2 NHis5 | 2.00(1) | 4(1) | 2.61 | 12.8 | |

| 1 NHis5 | 2.16(1) | 1(1) | |||

| 1 N/O | 2.00(1) | 3(2) | |||

| 1 Br | 2.39(1) | 4.8(5) | |||

| H152A Zn-HpUreE | 2 NHis5 | 2.01(1) | 6.7(5) | 1.85 | 3.96 |

| 2 N/O | 2.01(1) | 6.7(5) | |||

| 1 Br | 2.39(1) | 3.4(2) |

The superscripted number is the angle α for the His ligands.

A weakening of the Ni2+ complex formation was observed upon mutagenesis of His152, with the dissociation constant increasing from 0.15 μM in the wild type protein to 0.89 μM in the H152A mutant.[15] EXAFS analysis of the H152A Ni2+ site indeed reveals a significant change in the coordination environment, which could explain the change in the binding constants. The best fit of the EXAFS spectra for the H152A HpUreE mutant suggests the presence of only two coordinating histidine residues around Ni2+, together with four other N/O-donor ligands (Figure 5C, Table 3). Although still six-coordinate, the H152A HpUreE nickel-binding site is best fit using a single shell of ligands, as evident from single-scattering fits (Table SI-3). The multiple-scattering analysis (Table SI-4) shows that this shell contains only two histidine residues, presumably His102, with an angle α of 10°. This shell is complemented by four additional N/O-donor ligands at 2.09(1) Å. Therefore it is plausible that upon mutating the more weakly bound histidine residues (His152 most likely occurring at 2.15(1) Å in the wild type HpUreE) there is a rearrangement in the nickel binding site of HpUreE resulting in changes in the orientation of His102 to facilitate nickel coordination by an additional pair of N/O-donor ligands that compensate for the removal of His152.

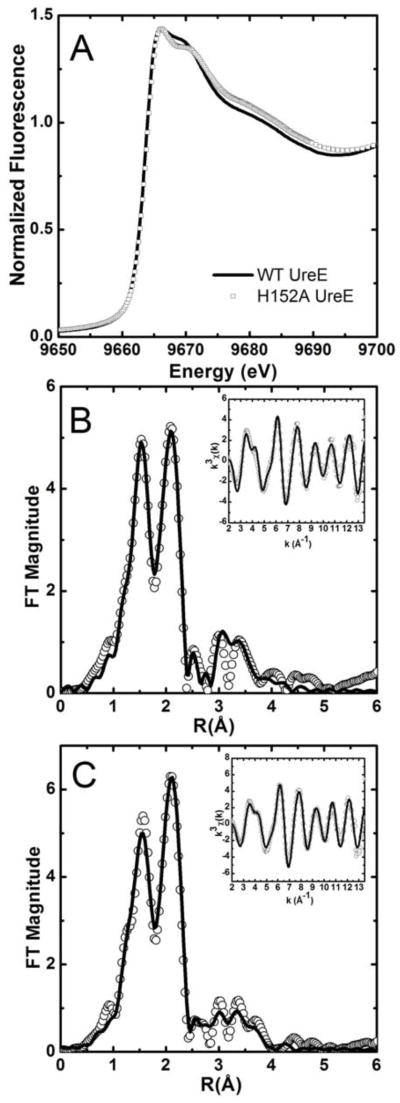

X-ray absorption spectroscopy on the Zn2+-binding site in wild type and H152A mutant HpUreE

The differences in the Zn K-edge XANES spectra of wild type and H152A Zn-HpUreE (Figure 6A) bound to one zinc equivalent are not significant and are consistent with a four- or five-coordinate Zn2+ site. The normalized fluorescence intensity approaches 1.5 at its maximum, which favors a five-coordinate over a four-coordinate binding site.44 Furthermore, the lack of resolution among the post-edge XANES features suggests that Zn2+ coordination is dominated by N/O donors.[44]

Figure 6.

(A) Zn K-edge XANES spectra of wild type and H152A Zn-HpUreE. (B) Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectra of wild type Zn-HpUreE (no phase correction, FT window = 2 – 13.5 Å−1). The inset shows the k3-weighted unfiltered EXAFS spectra: data (black line), best fit (white circles). (C) Fourier transformed Zn K-edge EXAFS spectra of H152A Zn-HpUreE (no phase correction, FT window = 2 – 13.5 Å−1). The inset shows the k3-weighted unfiltered EXAFS spectra: data (black line), best fit (white circles).

The EXAFS spectrum of wild type Zn-HpUreE is distinct from the Ni2+ complex and shows two features in the Fourier-transformed spectrum that indicate the presence of two scattering shells. For biological samples, this is consistent with a shell of N/O-donor ligands at 1.5 Å (in r-space, uncorrected for phase shifts), and a second shell of sulfur/halogens ligands at 2.0 Å.[45] Single-scattering fits suggest the presence of a bromide ligand in addition to five N/O-donors (Table SI-5). Features between 2.5 and 4 Å in r-space are generally attributed to histidine residues. Two models for wild-type Zn-HpUreE emerge from the multiple-scattering analysis. The best-fit model consists of three histidine residues arranged in two shells (Figure 6B). The first shell at 2.00(1) Å consists of an N/O-donor ligand in addition to two histidine ligands with α = 5°. The second shell at 2.16(1) Å consists of a single histidine residue and an N/O-donor ligand, while a third shell contains a bromide ion at 2.39(1) Å. This model is in agreement with the crystallographically determined dimer of dimer wild type Zn-HpUreE crystal structure, which indicates that at least three histidine residues play a role in zinc coordination. Modeling the EXAFS with four histidine ligands did not improve the fit (Table SI-6). Although the model with three histidine ligands described above gives the best fit in terms of both goodness of fit (R-factor) and reduced χ2, it is not statistically distinct from a second model with only two histidine ligands (Table 3). The difference in reduced χ2 for the two models differ by only a factor of 1.4, and not the optimal 1.8 that would allow the two-histidine model to be ruled out.

Removal of the His152 pair in the H152A mutant HpUreE results in a zinc-binding site that is also five-coordinate and has a bound bromide at 2.39(1) Å. However, only two histidine residues are readily simulated in the EXAFS analysis, which together with two other N/O-donor ligands, form a scattering shell at 2.01(1) Å (Table 3, Figure 6C, Tables SI-7 and SI-8).

In summary, the best descriptions of the metal-binding sites from XAS analysis indicate that in wild type HpUreE the Ni2+ site is six-coordinate with six N/O-donors, of which four are histidine ligands, and the Zn2+ site is five-coordinate with two or three histidine ligands and a bromide ion. In H152A HpUreE, a six-coordinate (N/O)6Ni site is retained but includes only two HisN-donor ligands. Similarly, the corresponding Zn2+ site in H152A HpUreE retains a five-coordinate (N/O)4Br site that is similar to the wild type Zn2+ site, but contains only two HisN-donor ligands.

DISCUSSION

This work represents an attempt to clarify the role of the disordered C-terminal portions of the two protomers in homodimeric UreE proteins in the metal binding and release steps that occur when UreE acts as a metallo-chaperone in the process of nickel insertion in the urease active site. A role for the C-terminal protein region was initially suggested in the case of BpUreE by metal binding experiments coupled with X-ray absorption spectroscopy, which indicated the presence of a binuclear Ni2+ binding site involving the fully conserved His100 as well as the C-terminal histidine residues.[22] Subsequently, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) coupled to site directed mutagenesis indicated that binding of a single Zn2+ or Ni2+ ion to the homodimeric HpUreE involves His102 on the protein surface, and that mutation of His152 on the disordered C-terminal arm alters the metal binding properties of the protein.[15] While Ni2+ is essential for enzymatic activity, being present in the active site of the functional urease enzyme, Zn2+ has been found to mediate and stabilize the interaction between H. pylori UreE and UreG in vitro.[15] UreG is another accessory protein with a GTPase role in the metallocenter assembly, suggesting a possible functional role for zinc, in addition to nickel, in this process.[15] So far, structural information on the nickel and zinc metal binding environment of the homodimeric functional form of UreE has been hindered by protein oligomerization, occurring in the solid state, coupled with the molecular disorder of the HpUreE C-terminal region, which is known to be involved in metal binding based on solution studies. In particular, while the crystal structure of apo-UreE from H. pylori was determined to be a dimer, the metal-bound form was described as a tetramer, or a dimer of dimers, with one metal ion bound between the four protein subunits.[19] A similar tetrameric arrangement was observed around a single Zn2+ ion in a structural study of BpUreE.[18] These observations prompted us to investigate further the Ni2+ and Zn2+ binding properties of HpUreE both in the solid state, using X-ray crystallography, and in solution, using X-ray absorption spectroscopy. This multifaceted approach yields consistent results that are in agreement with previous calorimetric studies, and reveals the structural details of the coordination environment of a single Ni2+ or Zn2+ ion bound to a single protein homodimer. The key role played by the conserved histidine ligands in the C-terminal arm of each protomer is thus demonstrated, and the protein motif is observed to gain significant structural ordering upon metal binding.

A comparison of all the HpUreE models (two apo dimers, two Zn2+-bound dimers, one Ni2+-bound dimer from this study, as well as the previously reported apo and Ni-bound structures) indicates some flexibility of the protein through the linker chain connecting the central domain. The central domain consists of two C-terminal halves of the protein, dimerizing head-to-head, and two peripheral N-terminal domains. Based on temperature factors and root mean square deviations, the most mobile parts of the models are the loops between strands 1 and 2 and between strands 5 and 6 on the surface of the N-terminal domain. The most disordered region is found towards the end of the C-terminal region, which, in the best case, becomes untraceable in electron density maps after residue Gly154.

In the crystal structures presented herein, a single metal ion (Ni2+ or Zn2+) is found per protein dimer, in agreement with the stoichiometry previously obtained using isothermal titration calorimetry.[15] This metal ion is coordinated by two His102 residues, one from each UreE monomer subunit. This arrangement, suggestive of a pair of tweezers, holds the metal cation on the surface of the protein dimer. The rest of the coordination environment involves the C-terminal segment, which is in contact with the metal ions through His152. This protein region is not visible in the apo-protein, but becomes significantly more ordered upon metal binding. Nevertheless, some disorder in the electron density was still observed. The data suggest that the HpUreE binding arrangement, stable on one side and transient on the other, can be easily disengaged, and thus represents a fine balance between binding the metal ion and releasing it to its partners, a balance that is necessary for the chaperone function of UreE in nickel trafficking.

In the crystal structure, the coordination of the Zn2+ site is tetrahedral, while the Ni2+ ion adopts an axially elongated distorted octahedral site that is approximately square bipyramidal. This reflects the intrinsic coordination preferences of the two metal ions, with Zn2+ being d10 and closed-shell, having no stereo-electronic preferences and leading to a coordination number and geometry imposed only by steric constraints, while Ni2+, being d8 and open-shell, has stereo-electronic preferences towards a tetragonal 4+2 coordination geometry due to the ligand field stabilization energy. The ability of the different cations to achieve their preferred coordination number in the complex with UreE indicates a significant flexibility of the protein. Indeed, the angle His102 Nε2 - Ni2+ - His102 Nε2 is close to 90° and it becomes 106–109° with Zn2+. The other ligands also appear in appropriate positions and numbers. The arrangement of the protein around the Ni2+ ion is more open. In addition to the pair of His102 residues and a pair of His152, the Ni2+ ion takes two additional ligands (a water and Glu4′ from a neighboring protein molecule in the crystal lattice). The Zn2+ is surrounded by the two pairs of histidine residues, His102 and His152 (with one of the latter histidine ligands possibly displaced by Glu154D).

Conclusions

The structural features of HpUreE established in this study allow us to propose a role for the C-terminal portions of the UreE dimer in molecular recognition and metal ion delivery. In particular, the observations strongly support the idea that UreE could exist in two different conformations. In a “closed” state the delivered metal ion would be bound to the protein through the two conserved His102 residues (H. pylori numbering) and to histidine residues invariably found in the C-terminal region of this class of proteins (His152 in the case of HpUreE). The C-terminal region, disordered in the absence of the metal but gaining order upon metal binding, would change into an “open” state when protein-protein interactions between UreE and a partner protein, or protein complex, prone to receive the metal ion are present. In this form, His152 and analogous residues would be substituted by amino acid residues located on the surface of the protein partner receiving the metal ion from UreE.

Different roles of HpUreE bound to Ni2+ and Zn2+ are suggested by the observation that zinc, but not nickel, stabilizes the interaction between HpUreE and its cognate GTPase HpUreG.[15] The cross-talk between UreE, Ni2+ and Zn2+ suggests a specific functional role for different metal complexes of this urease accessory protein in regulating the formation of protein-protein complexes involved in enzyme maturation. This study has shown that the metal ion selectivity of UreE is based on the different metal ion coordination environments that are dictated by the electronic properties of the metal ion in a mechanism that is facilitated by the flexibility of the C-terminal protein region.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement No.226716 (WR), NIH grant R01-GM-69696 (MJM), and from the Italian Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca PRIN2007 (SC). We acknowledge the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin - Electron storage ring BESSY II for provision of synchrotron radiation at beamlines 14.1 and 14.2. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program.

Abbreviations

- Hp

Helicobacter pylori

- Bp

Bacillus pasteurii

- Ka

Klebsiella aerogenes

- Mj

Methanocaldococcus jannaschiii

- His

H, histidine

- Glu

glutamate

- Gln

glutamine

- Gly

glycine

- A

alanine

- GTP

Guanosine-5′-triphosphate

- Tris

2-amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol

- MAD

multiwavelength anomalous dispersion; isothermal titration calorimetry

- Kd

equilibrium dissociation constant

- GeV

Giga electron Volt

- XANES

X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure

- rmsd

root mean square deviation

- MALS

multiple angle light scattering

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

References

- 1.Carter EL, Flugga N, Boer JL, Mulrooney SB, Hausinger RP. Interplay of metal ions and urease. Metallomics. 2009;1:207–221. doi: 10.1039/b903311d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zambelli B, Musiani F, Benini S, Ciurli S. Chemistry of Ni2+ in urease: sensing, trafficking, and catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:520–530. doi: 10.1021/ar200041k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callahan BP, Yuan Y, Wolfenden R. The burden borne by urease. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10828–10829. doi: 10.1021/ja0525399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabri E, Carr MB, Hausinger RP, Karplus PA. The crystal structure of urease from Klebsiella aerogenes. Science. 1995;268:998–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benini S, Rypniewski WR, Wilson KS, Miletti S, Ciurli S, Mangani S. A new proposal for urease mechanism based on the crystal structures of the native and inhibited enzyme from Bacillus pasteurii: why urea hydrolysis costs two nickels. Structure. 1999;7:205–216. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha NC, Oh ST, Sung JY, Cha KA, Lee MH, Oh BH. Supramolecular assembly and acid resistance of Helicobacter pylori urease. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:505–509. doi: 10.1038/88563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balasubramanian A, Ponnuraj K. Crystal structure of the first plant urease from jack bean: 83 years of journey from its first crystal to molecular structure. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quiroz S, Kim JK, Mulrooney SB, Hausinger RP. Nickel and its surprising impact in nature. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2007. Chaperones of nickel metabolism; pp. 519–544. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mobley HLT, Hausinger RP. Microbial urease: significance, regulation and molecular characterization. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:85–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.85-108.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mobley HLT, Island MD, Hausinger RP. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:451–480. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.451-480.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park IS, Hausinger RP. Metal ion interactions with urease and UreD-urease apoproteins. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5345–5352. doi: 10.1021/bi952894j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park IS, Hausinger RP. Requirement of carbon dioxide for in vitro assembly of the urease nickel metallocenter. Science. 1995;267:1156–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.7855593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soriano A, Colpas GJ, Hausinger RP. UreE stimulation of GTP-dependent urease activation in the UreD-UreF-UreG-urease apoprotein complex. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12435–12440. doi: 10.1021/bi001296o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MH, Mulrooney SB, Renner MJ, Markowicz Y, Hausinger RP. Klebsiella aerogenes urease gene cluster: sequence of ureD and demonstration that four accessory genes (ureD, ureE, ureF, ureG) are involved in nickel metallocenter biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4324–4330. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4324-4330.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellucci M, Zambelli B, Musiani F, Turano P, Ciurli S. Helicobacter pylori UreE, a urease accessory protein: specific Ni2+ and Zn2+ binding properties and interaction with its cognate UreG. Biochem J. 2009;422:91–100. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boer JL, Quiroz-Valenzuela S, Anderson KL, Hausinger RP. Mutagenesis of Klebsiella aerogenes UreG to probe nickel binding and interactions with other urease-related proteins. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5859–5869. doi: 10.1021/bi1004987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song HK, Mulrooney SB, Huber R, Hausinger RP. Crystal structure of Klebsiella aerogenes UreE, a nickel-binding metallochaperone for urease activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49359–49364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Remaut H, Safarov N, Ciurli S, Van Beeumen J. Structural basis for Ni2+ transport and assembly of the urease active site by the metallochaperone UreE from Bacillus pasteurii. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49365–49370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi R, Munger C, Asinas A, Benoit SL, Miller E, Matte A, Maier RJ, Cygler M. Crystal structures of apo and metal-bound forms of the UreE protein from Helicobacter pylori: role of multiple metal binding sites. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7080–7088. doi: 10.1021/bi100372h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benoit S, Maier RJ. Dependence of Helicobacter pylori urease activity on the nickel-sequestering ability of the UreE accessory protein. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4787–4795. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4787-4795.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MY, Pankratz HS, Wang S, Scott RA, Finnegan MG, Johnson MK, Ippolito JA, Christianson DW, Hausinger RP. Purification and characterization of Klebsiella aerogenes UreE protein: a nickel binding protein that functions in urease metallocenter assembly. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1042–1052. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stola M, Musiani F, Mangani S, Turano P, Safarov N, Zambelli B, Ciurli S. The nickel site of Bacillus pasteurii UreE, a urease metallo-chaperone, as revealed by metal-binding studies and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6495–6509. doi: 10.1021/bi0601003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musiani F, Zambelli B, Stola M, Ciurli S. Nickel trafficking: insights into the fold and function of UreE, a urease metallochaperone. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:803–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–325. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panjikar S, Parthasarathy V, Lamzin VS, Weiss MS, Tucker PA. Auto-Rickshaw: an automated crystal structure determination platform as an efficient tool for the validation of an X-ray diffraction experiment. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:449–457. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.La Fortelle Ed, Bricogne G. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for the MIR and MAD methods. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276 doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowtan K, editor. An automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Daresbury Laboratory; Warrington, WA4 4AD, UK: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris RJ, Zwart PH, Cohen S, Fernandez FJ, Kakaris M, Kirillova O, Vonrhein C, Perrakis A, Lamzin VS. Breaking good resolutions with ARP/wARP. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2004;11:56–59. doi: 10.1107/s090904950302394x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collaborative Computational Project, N. The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldrick GM. Macromolecular phasing with SHELXE. Z Kristallogr. 2002;217:644–650. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb SM. Sixpack: A graphical user interface for XAS analysis using IFEFFIT. Physica Scripta. 2005;T115:1011–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravel B, Newville M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2005;12:537–541. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505012719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zabinsky SI, Rehr JJ, Ankudinov A, Albers RC, Eller MJ. Multiple scattering calculations of x-ray absorption spectra. Phys Rev B. 1995;52:2995–3009. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.52.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newville M. EXAFS analysis using FEFF and FEFFIT. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2001;8:96–100. doi: 10.1107/s0909049500016290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engh RA, Huber R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta Cryst. 1991;A47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackburn NJ, Hasnain SS, Pettingill TM, Strange RW. Copper K-extended x-ray absorption fine structure studies of oxidized and reduced dopamine beta-hydroxylase. Confirmation of a sulfur ligand to copper(I) in the reduced enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23120–23127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira GC, Franco R, Mangravita A, George GN. Unraveling the substrate-metal binding site of ferrochelatase: An X-ray absorption spectroscopic study. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4809–4818. doi: 10.1021/bi015814m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colpas GJ, Maroney MJ, Bagyinka C, Kumar M, Willis WS, Suib SL, Baidya N, Mascharak PK. X-ray spectroscopic studies of nickel complexes, with application to the structure of nickel sites in hydrogenases. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:920–928. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacquamet L, Aberdam D, Adrait A, Hazemann JL, Latour JM, Michaud-Soret I. X-ray absorption spectroscopy of a new zinc site in the Fur protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2564–2571. doi: 10.1021/bi9721344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strange RW, Blackburn NJ, Knowles PF, Hasnain SS. X-ray absorption spectroscopy of metal-histidine coordination in metalloproteins. Exact simulation of the EXAFS of tetrakis(imidazole)copper(II) nitrate and other copper-imidazole complexes by the use of a multiple-scattering treatment. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:7157–7162. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.