Abstract

CRH neuroendocrine neurones in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) drive ACTH and thereby glucocorticoid release from pituitary corticotrophs and adrenal cortex respectively. Glucocorticoids suppress the ability of neuroendocrine CRH neurons to synthesise and release ACTH secretogogues. Despite the importance of glucocorticoids as regulatory signals to CRH neurones in the extended time domain, how and where they act in this capacity is still not fully understood. Ascending catecholamine projections encode important cardiovascular, metabolic, and other visceral information to the rat PVH and surrounding hypothalamus. These afferents have previously been implicated as targets for glucocorticoid action, including a role in the feedback regulation of PVH neuroendocrine neurones. To determine the contribution of these neurones to corticosterone’s long-term actions on CRH and vasopressin (AVP) gene expression in the PVH we used an immunocytotoxin (a conjugate of the cytotoxin saporin and an antibody against dopamine-β-hydroxylase) that specifically ablates adrenergic and noradrenergic neurones. Lesions were administered to intact animals and to adrenalectomized animals with either no corticosterone or corticosterone replacement that provided levels above those required to normalise Crh expression. The ability of elevated levels of corticosterone to suppress Crh expression was abolished in animals lacking catecholaminergic innervation of the PVH. No effect was seen in the absence of corticosterone or in animals with intact adrenals. Furthermore, Avp expression, which is increased in CRH neurons following adrenalectomy, was suppressed in adrenalectomized catecholaminergic lesioned animals. Interactions between corticosterone and catecholaminergic projections to the hypothalamus therefore make significant contributions to the regulation of Crh and Avp expression. However, the importance of catecholamine inputs is only apparent when circulating corticosterone concentrations are maintained either below or above those required to maintain the activity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis that is seen in intact animals.

Keywords: Hypothalamus, ACTH secretogogue, Body weight, Metabolism, Stress, Amygdala

INTRODUCTION

One of the most well-studied neuroendocrine regulatory mechanisms is the one used by glucocorticoid to suppress activity in the upstream components of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [1–6]. Increasing circulating corticosterone concentrations in rats suppress synthesis and release processes at the level of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) and corticotropes in the pituitary gland. The ability of glucocorticoid to dampen the synthetic and release activity of the principal ACTH secretogogues, CRH and vasopressin (AVP), over extended periods in PVH neuroendocrine CRH neurones (‘slow feedback’) is very well-described, and remains a cornerstone for considering how the HPA axis is controlled [1–6].

Although a substantial body of evidence has characterised the ability of glucocorticoids to suppresses Crh expression and CRH peptide levels [7–11], a complete understanding of the underlying mechanism still remains elusive [6]. There is some support for direct actions of corticosterone on CRH neurons, including interactions with Crh [reviewed in 12], but much evidence points to the ability of corticosterone to alter the activity of important sets of PVH afferents, which then figure prominently in the suppression of Crh activity [reviewed in 6]. For example, parts of the hippocampal formation contain high concentrations of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [13,14] that can influence CRH neuroendocrine function in the PVH by way of projections involving the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis (BST) [15,16]. This network has long been considered instrumental for glucocorticoids to control CRH neuroendocrine neurons, particularly in dampening HPA responses during extended episodes of stress [17].

The PVH and adjacent regions of the hypothalamus also receive a robust set of afferents from the hindbrain, a significant proportion of which are catecholamine-containing projections [18,19]. We have already established that catecholaminergic afferents are required for CRH neuroendocrine neurones to respond rapidly to glycemic challenges [20–22]. Their ability to mediate short-term responses to other stressors has also been reported [23]. But the function of catecholaminergic pathways in the absence of stressors is less clear, and may be different from that seen during stress. These inputs are clearly not required to maintain daily variations of corticosterone section [20], but electrophysiological studies suggest at least some role in corticosterone’s mechanism of action on CRH neurons [24,25]. There is also evidence that catecholaminergic pathways can directly affect CRH synthesis in these neurons, and that corticosterone can influence this interaction [26–28]. However, other studies report little effect [5].

We now reexamine the hypothesis that interactions between corticosterone, catecholamine projections from the hindbrain, and CRH neuroendocrine neurones in the PVH are significant contributors to slow glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms [see also 28,29]. To do this we ablate this critical PVH afferent system using an immunotoxin that provides much greater specificity than physical or pharmacological methods [20,30]. We then use in situ hybridization to measure the ability of corticosterone to suppress Crh and Avp expression in the slow time domain [2,6]. We employ the well-established experimental design where circulating corticosterone in adrenalectomized (ADX) rats is clamped with slow-release pellets for 7 days [5,11,31,32].

METHODS

Animals

48 Sprague-Dawley rats (300g BW at the time of surgery; Harlan Laboratories) were maintained on a 12h:12h light/dark schedule (lights on at 06.00h clock time) in a temperature-controlled room with continuous access to a chow diet (Teklad rodent diet 8604) and water. All animals were acclimatised in the vivarium for at least 10 days before beginning any procedure. Surgeries were performed under continuously administered 2–3% isoflurane/oxygen anesthesia. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care And Use Committee of the University of Southern California.

Stereotaxic Surgery

Bilateral microinjections of 42ng/200nl dose of saporin conjugated to a mouse polyclonal antibody against dopamine β-hydroxylase (DSAP; Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA), or an equivalent dose of saporin conjugated to mouse IgG (mIgG-SAP; Advanced Targeting Systems) were delivered to the PVH as previously described [20,22]. Gentomicin (0.01mg/kg) and flumeglumine (0.01mg/kg) were injected intramuscularly to all rats immediately following surgery.

Adrenalectomy

Seven to ten days after stereotaxic surgery rats were randomly assigned to two groups. The first group was bilaterally adrenalectomized (ADX) and immediately implanted subcutaneously with either 0mg, 25mg, 50mg, or 100mg slow-release (21 days) corticosterone pellets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) [11] to ensure a suitable range of plasma corticosterone concentrations at end of the experiment. Animals given the 0mg pellet constituted the ADX-only group. The second group remained intact but were give sham surgical procedures.

All rats were returned to the vivarium for a further 7 days. ADX rats were offered unrestricted access to 0.9% saline and water. Body weights were measured at the time of DSAP/MIgG-SAP surgery, ADX (or equivalent day for intact animals), and at perfusion. 24h food intakes of all rats were also measured during the 3 days immediately preceding perfusion. The three daily values from each animal were then averaged and the resulting value used in subsequent statistical analyses. It should be noted that not all animals within any one treatment group provided data for every dependent variable.

Animals injected with either DSAP (n=22) or MIgG-SAP (n=26) were assigned to one of two treatment groups based on their surgical procedure (ADX, n=37; or intact, n=11). The ADX group was then further subdivided based on their plasma corticosterone concentrations at the time of perfusion: ADX rats with placebo pellets (with plasma corticosterone concentrations at or below the limit of assay sensitivity, n=14); and ADX animals bearing the 25mg 100mg pellets that had terminal plasma corticosterone concentrations between 51–120 ng/ml (ADX+Hi-CORT, n=23). This generated six experimental groups in total.

These group criteria are based on previous studies showing that Crh expression in the PVH of unstressed animals is most sensitive to plasma corticosterone concentrations between 0 and 120ng/ml, and that 20–30ng/ml is sufficient to return CRH mRNA levels to those found in intact animals [5,11]. Plasma corticosterone concentrations between 51–120 ng/ml significantly reduce CRH mRNA levels compared to intact animals [11]. Concentrations above 120ng/ml have markedly diminished ability to reduce Crh expression, while those above 200ng/ml have no further suppressive effect. These corticosterone concentrations are somewhat lower than those reported by Akana and colleagues [32] to normalise body and thymus weights, and circulating ACTH concentrations. They found that a range of 45–75 ng/ml normalised these particular variables.

Perfusion and Tissue Processing

All animals were anaesthetised and perfused 7 days after corticosterone replacement, which was at least 14 days after lesion surgery thereby ensuring the full development of the DSAP lesion [20,30]. Perfusions were performed between 09.00h and 13.00h under tribromoethanol anesthesia [31]. A blood sample was taken from the external jugular vein into heparinised tubes. Plasma was separated by centrifugation, stored at −20°C, and used later for plasma corticosterone determination. Immediately after taking the blood sample animals were perfused transcardially with potassium phosphate buffered saline (KPBS) for approximately 1–2 minutes, 4% paraformaldehyde buffered in 0.1M acetate (pH 6.5, 250mls) for rapid diffusion into tissue (approximately 5–7 minutes) and 4% paraformaldehyde buffered in 0.1M borate (pH 9.5, 500mls) for deep penetration into tissues (approximately 7–10 minutes).

After completing the perfusion, the thymus gland was removed, placed in 0.9% saline, dissected free from adjacent connective and adipose tissue, blotted dry, and weighed. Brains were removed and immediately placed in a chilled solution of 4% paraformaldehyde/borate containing 12% sucrose. Brains were kept at 4°C overnight, rinsed with KPBS, frozen with super cooled hexane on dry ice, and then stored at −70°C until sectioned.

A sliding microtome was used to cut eight series of 1:8 20μm frozen sections through the hypothalamus from approximately level 23 to level 30 of Swanson [33]. Four series were stored in cryoprotectant at −20°C for immunocytochemistry or thionin staining for cytoarchitechtonics, while the the remaining series were prepared for in situ hybridization analyses, as previously described [31].

In Situ Hybridization

Previously described methods for radioisotopic (35S) in situ hybridization [31] were used to measure two RNAs: CRH mRNA in the dorsal medial parvicellular (mpd) part of the PVH and central nucleus of the amygdala (CEA); and AVP heteronuclear RNA (hnRNA) in the PVHmp, posterior magnocellular (pm) part of the PVH, and supraoptic nucleus (SO). We have previously shown that CRH and AVP hn and mRNAs all show the appropriate set of responses following extended CORT exposure [31].

In brief, sections were hybridised with either a [35S]UTP-labeled cRNA probe transcribed from a 700-bp cDNA sequence encoding RNA for part of the prepro-CRH sequence, or a 700-bp PvuII fragment of intron 1 of Avp. cRNA probes were synthesised using the Gemini kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and the appropriate RNA polymerase. The characterization of all probes has been reported previously [31].

Film exposure times CRH mRNA were 20h (PVHmp) and 4 days (CEA), and 9 days for AVP hnRNA. Adjacent Nissl-stained sections and the Swanson rat brain atlas [33] were used to designate the anatomical boundaries of all regions of interest. The mean grey levels (MGL) of all RNA in situ hybridization signals was measured in anatomically defined regions using IPLab Spectrum (v3.9; Scananalytics, Inc., Fairfax, VA) as previously described [31].

Immunohistochemistry

The effect of the DSAP lesion on the dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)-immunoreactive terminal field in the PVH was assessed in all rats using a mouse monoclonal antibody to DBH (1:10K; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and an anti-mouse IgG conjugated to CY-3 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), as described previously [22]. The PVH was imaged at approximately level 26 of Swanson [33] using a Zeiss AxioImager fluorescence microscope. For animals with DSAP-lesions, only those with 30% or less of control levels of DBH-ir in left and right PVH [22] were retained for analysis.

Radioimmunoassay

The efficacies of adrenalectomy and corticosterone replacement were determined by measuring circulating corticosterone concentrations in the terminal blood samples using a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit (ICN Biochemicals, Costa Mesa, CA) with modifications as previously noted [31]. The lower sensitivity limit was 6.25 ng/ml. Plasma samples from all animals were assayed together in a single assay with an intraassay coefficient of variation of less than 8%.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between group means was determined using two-factor ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. Student’s t-test was used to compare significant differences between mIgG-SAP and DSAP animals in AVP hnRNA in the PVHmp and CRH mRNA in the CEA. Excel (2004; Microsoft Corp., Redwood, WA) and Prism (Mac v4, GraphPad Software) were used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

Plasma Corticosterone Concentrations and Thymus Weight

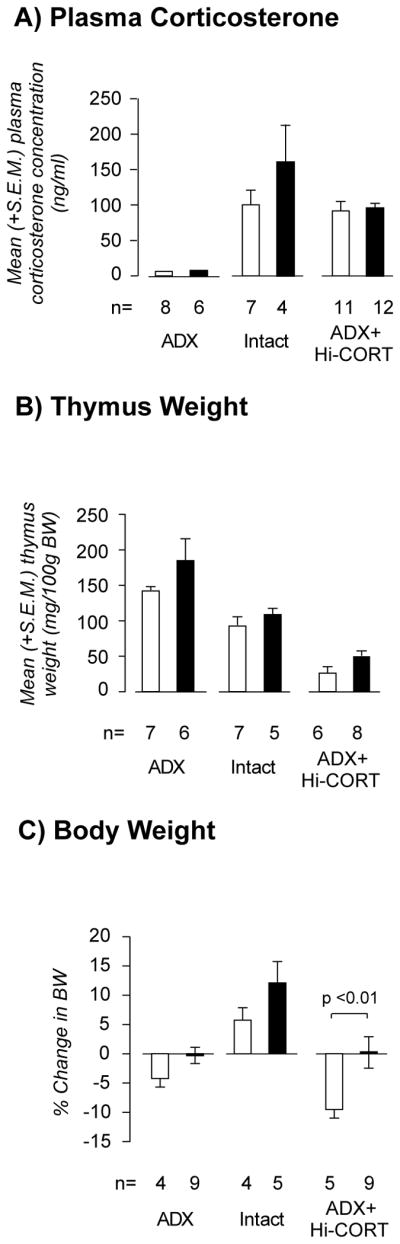

Figure 1A shows that plasma corticosterone concentrations were at or below the assay sensitivity level in both ADX groups (MIgG-SAP and DSAP), while the mean concentration in both ADX-Hi Cort groups was approximately 100ng/ml and not significantly different between unlesioned and lesioned animals. Markedly elevated plasma corticosterone concentrations were found in intact rats (Fig. 1A). However, it should be noted that these values do not reflect unstressed values because they were taken under anesthesia immediately before perfusion. Intact animals were assumed to have effective plasma corticosterone concentrations intermediate between the ADX and ADX + Hi-Cort groups during the experimental period, an assertion supported by their thymus gland weights (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Mean (± S.E.M.) terminal plasma corticosterone concentrations (A), thymus weights (B), and seven day change in body weights (C) in adrenalectomized (ADX), intact, and ADX animals with corticosterone replacement (ADX+Hi-Cort) given either a MIgG-saporin injection (open bars) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin (solid bars) injection into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Numbers of animals (n) is shown for each group. See text for further details on the levels of statistical significance.

Thymus weights provide an accurate reflection of plasma corticosterone concentrations integrated over long periods [see 11,31]. Figure 1B shows that within the unlesioned or lesion group there were highly significant differences in thymus weight between the three treatment groups. Two factor ANOVA revealed no interaction between the corticosterone manipulations and the MIgG-SAP/DSAP lesions (F=[2,33] = 0.09, P=0.9174). There was a significant main effect of the corticosterone manipulation on thymus weight (F=[2,33] = 41.25, P<0.0001), but no significant differences between MIgG-SAP and DSAP groups in any of the corticosterone groups.

Body Weight and Food Intake

Figure 1C shows the changes in body weight during the final 7 days of the experiment. For both MIgG-SAP and DSAP animals, the intact groups increased body weight compared to the ADX and the ADX+Hi Cort groups, which both lost weight. There was no interaction between the corticosterone manipulations and the MIgG-SAP/DSAP lesions (F=[2,30] = 1.408, P=0.2603). There was a significant main effect of the corticosterone manipulation on body weight (F=[2,30] = 20.06, P=0.0001) with a significant difference between MIgG-SAP and DSAP groups in the ADX-Hi-Cort animals. The greatest differential change in body weight between unlesioned and lesioned animals was seen in the two ADX+Hi-Cort groups (approximately 10%). This loss was eliminated in lesioned ADX+Hi-Cort animals, whose change in body weight was approximately zero and was equivalent to that seen in the lesioned ADX group.

Table 1 shows that mean total amount of food consumed per 24h during the 3 days before perfusion. There was no interaction between the corticosterone manipulations and the MIgG-SAP/DSAP lesions (F=[2,18] = 2.94, P=0.08). There was a small but significant main effect of the corticosterone manipulation on chow intake (F=[2,18] = 4.49, P<0.05), and a significant difference between MIgG-SAP and DSAP groups in the ADX-Hi-Cort animals. This difference was not present when food intake was normalised to body weight, although the trend was the same as for total intake.

Table 1.

Mean (± S.E.M.) daily food intake (average from the final 3 days of the experiment) from adrenalectomized (ADX), intact, and ADX animals with corticosterone replacement (ADX+Hi-Cort) given either a MIgG-saporin injection (MIgG-SAP) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin (DSAP) injection into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Numbers of animals (n) is shown for each group. Food intake is expressed as total grams consumed and amount consumed per 100g body weight (BW).

| MIgG-SAP | DSAP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADX | Intact | ADX + Hi Cort | ADX | Intact | ADX + Hi Cort | |

| Total food/24h (g) | 21.7 ± 0.2 | 21.5 ± 1.2 | 16.6 ± 1.4 | 24.9 ± 0.3 | 22.4 ± 0.9 | 22.7 ± 1.5* |

| g/100g BW | 6.46 ± 0.08 | 7.20 ± 0.43 | 6.40 ± 0.43 | 7.42 ± 0.11 | 6.75 ± 0.49 | 7.29 ± 0.45 |

| n | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

P<0.05 vs MIgGSAP ADX + Hi Cort

Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Gene Expression in the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus

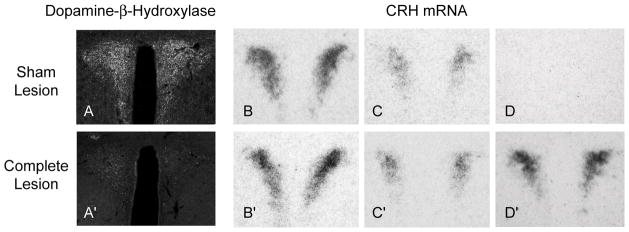

Figures 2A and 2A′ shows that dopamine-β-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the PVH was virtually eliminated 14 days after a DSAP injection compared to MIgG-SAP injections. We and others have previously noted that this denervation is not limited to the PVH, and DBH-ir is also lost elsewhere in the hypothalamus and adjacent forebrain following DSAP injections in the PVH [22,34]

Figure 2.

The effect of a MIgG-saporin (Sham Lesion) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)-saporin (DSAP; Complete Lesion) injection into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) on DBH immunoreactivity (A, A′) and CRH mRNA levels in the PVH (B–D, B′–D′). Sham lesioned animals showed progressively lower levels of CRH mRNA from adrenalectomized (B), intact (C) to adrenalectomized animals with corticosterone replacement (D). Complete DSAP lesions had no effect on CRH mRNA levels in adrenalectomized (B′) and intact (C′) animals, but eliminated the ability of elevated levels of corticosterone to suppress CRH mRNA (D, D′).

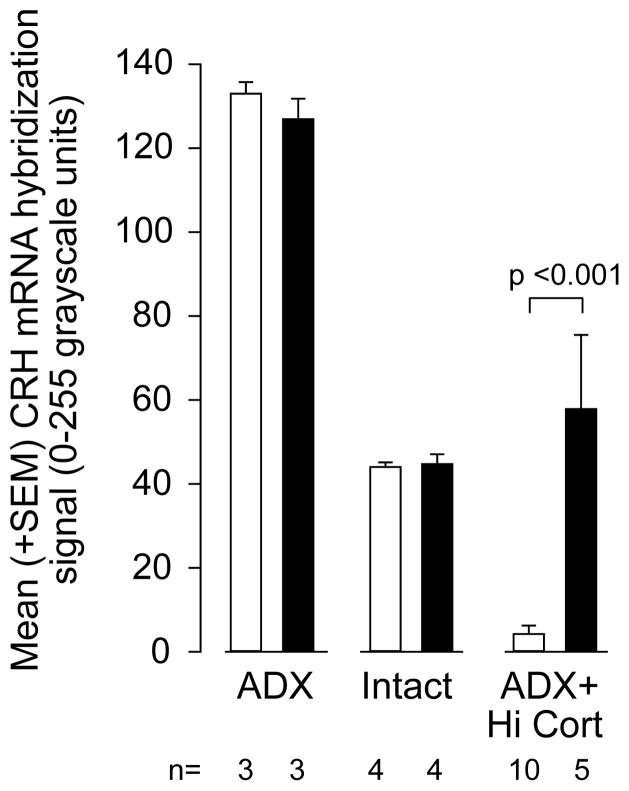

As expected, there was a highly significant difference in CRH mRNA levels in the PVHmp between ADX, intact, and ADX+Hi-Cort animals (Figs 2 & 3). Thus, there was a significant interaction between corticosterone manipulation and the DSAP lesion (F=[2,24] = 10.76, P<0.0005), with post-hoc analysis showing a highly significant difference between the MIgG-SAP and DSAP animals in the ADX-Hi-cort group (p<0.001), but not the other two groups. In this way CRH mRNA levels in lesioned ADX+Hi-Cort animals were indistiguishable from those in intact lesioned animals, with some lesioned ADX+Hi-Cort animals showing even higher CRH mRNA levels than those in intact animals (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mean (± S.E.M.) CRH mRNA levels in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) in adrenalectomized (ADX), intact, and ADX animals with corticosterone replacement (ADX+Hi-Cort) given either a MIgG-saporin injection (open bars) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin (solid bars) injection into the PVH. Numbers of animals (n) is shown for each group. See text for further details on the levels of statistical significance.

Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Gene Expression in the Central Nucleus of the Amygdala

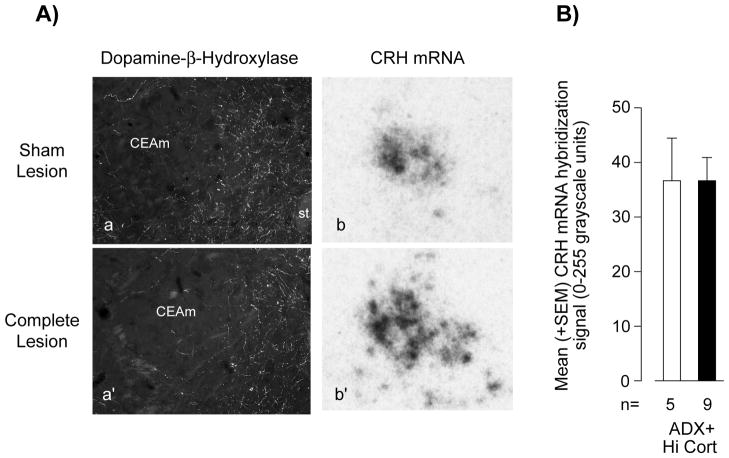

Corticosterone has previously been shown to exert a stimulatory effect on Crh expression in the CEAm [5,10,11]. We also found increasing CRH mRNA levels from ADX to ADX Hi-Cort animals in this experiment (data not shown). Importantly however, Figures 4A and 4Aprime; show that a DSAP injection into the PVH had virtually no effect on the dopamine-β-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the CEA. Unlike CRH mRNA in the PVHmp, there was no significant difference in CRH mRNA levels in the lateral part of the CEA of lesioned ADX+Hi-Cort animals compared to those in unlesioned ADX+Hi-Cort animals (Fig. 4). No effects of the DSAP lesion were seen on CRH mRNA levels in the CEAm of ADX or intact animals (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The effect of a MIgG-saporin injection (Sham Lesion) or an anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)-saporin injection (Complete Lesion) into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) on DBH immunoreactivity in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CEA; Aa, Aa′) and CRH mRNA levels in the medial part of the CEA (Ab, Ab′; B) of adrenalectomized animals with corticosterone replacement (ADX+Hi-Cort). Abbreviations: CEAm, medial part of the central nucleus of the amygdala; st, stria terminalis. ns, not significant. Numbers of animals (n) is shown for each group.

Vasopressin Gene Expression in the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus and Supraoptic Nucleus

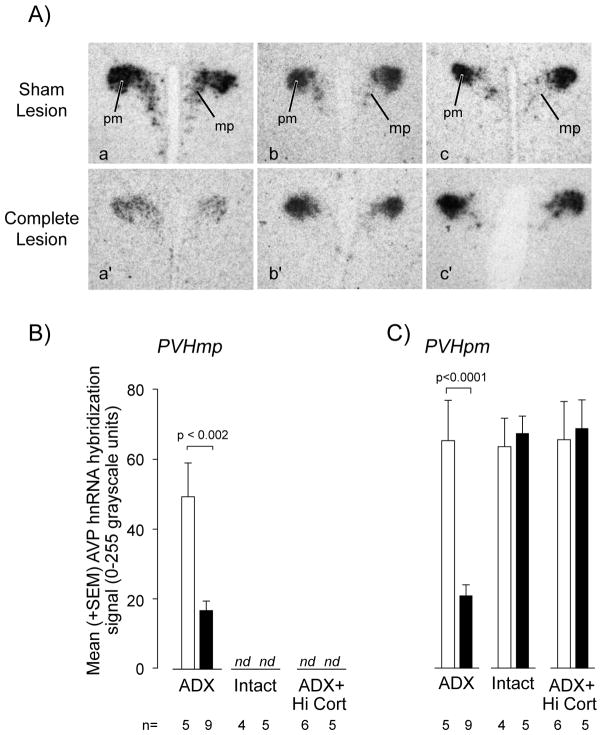

AVP is expressed in two functionally distinct parts of the PVH: the magnocellular PVHpm, which provides projections to the neural lobe of the pituitary; and in some neuroendocrine CRH neurones in the PVHmp that innervate the median eminence and stimulate ACTH secretion. Both PVH compartments are innervated by ascending CA projections, albeit from somewhat different sources [19]. Corticosterone has strongly suppressive effects on Avp expression in the PVHmp, but not the PVHpm [35].

We found that Avp expression was significantly suppressed in the PVHmp of the lesioned ADX group compared to unlesioned ADX animals (Figs. 5Aa & Aa′; 5B), but no lesion effects were evident in the other two groups levels where they remained below the level of detection (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

AVP hnRNA levels as measured by in situ hybridization (A) in the medial parvicellular (B) and posterior magnocellular (C) parts of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH) of adrenalectomized (ADX), intact, and ADX animals with corticosterone replacement (ADX+Hi-Cort) and given either a MIgG-saporin injection (Sham Lesion in A; open bars in B and C) or anti-dopamine-β-hydroxylase-saporin (Complete Lesion in A; open bars in B and C) injection into the PVH. See text for further details on the levels of statistical significance. Abbreviations: mp, medial parvicellular part of the PVH; pm, posterior magnocellular part of the PVH; nd, not detectable.

In the PVHpm there was a significant interaction between corticosterone manipulation and the DSAP lesion (F=[2,29] = 22.23, P<0.0001), with post-hoc analysis showing a highly significant difference between the MIgG-SAP and DSAP animals in the ADX-only group, but not the other two groups (Figs. 5Aa & Aa′, 5C). Avp expression was not altered in the PVHpm of intact and ADX+Hi-Cort animals (Figs. 5Ab, Ac & Ab′, Ac; 5C), or in the SO (data not shown) of any treatment or lesion group.

DISCUSSION

We show that the ability of corticosterone to suppress Crh expression in neuroendocrine CRH neurones is abolished when the hindbrain-originating catecholaminerigic inputs to the PVH and parts of the adjacent forebrain are ablated by the specific immunotoxin DSAP. This effect is not evident across all corticosterone concentrations, but is limited to concentrations above those required to maintain HPA function within the range seen in unstressed intact animals [5,11,32]. No effects of the lesion are seen on CRH mRNA levels in the PVHmp of ADX or intact animals. The effects of the lesion are restricted to the PVHmp and are not seen in the CEA where a corticosterone-sensitive group of CRH neurones is found in its lateral subdivision [5,10,11].

Before discussing our results in more detail, it is worth making a couple of technical points. First, because catecholaminergic neurons generate collaterals, it is not possible to restrict a lesion to the PVH. Previous studies have shown that catecholaminergic projections to the PVH also collateralize to parts of the BST, arcuate nucleus, and dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus [22,34]. Because these nuclei themselves project to the PVH, they may contribute to the effects we see here. Second, we use a tonic replacement regime for corticosterone that does not mimic the secretory patterns seen in intact animals. Because pulsatile glucocorticoid secretion can shape the way it regulates gene expression in the brain [36], it is not possible to rule out potential differences that may exist between the tonic replacement model we use here and adrenally intact animals.

DSAP lesions have quite different effects on Avp expression in the PVH. In the absence of corticosterone they suppress AVP hnRNA levels in PVHmp and PVHpm (but not the SO). The PVHmp findings are consistent with previous immunocytochemical results [28], but not in the PVHpm, where Sawchenko [28] found no suppression of AVP peptide. Our finding that AVP hnRNA is reduced in PVHpm neurons of DSAP lesioned ADX animals suggests that at reduced circulating corticosterone concentrations catecholaminergic inputs provide some sort of facilitatory signal to maintain elevated Avp expression. Our PVHmp results together with many others, emphasise that these two ACTH secretagogues are regulated in CRH neuroendocrine neurones by very different mechanisms, including those engaged by catecholamines [6,12,22,35,37].

Glucocorticoids have widespread effects on neurones throughout the brain [38,39] and on many physiological functions [40], making it likely that complex and diverse mechanisms contribute to the corticosterone/catacholamine interactions that impact the PVH. However, at least two non-exclusive candidate mechanisms are suggested by the fact that GRs are expressed by CRH neuroendocrine neurones and by neurones in their proximal control network (see [6] for review).

First, a number of studies support the idea that corticosterone acts directly on CRH neurones to modify the way they interact with catecholaminerigic afferents. Corticosterone may do this in a number of ways given that it modulates adrenoreceptor-dependent changes in the firing rate of PVH parvicellular neurones [24,25], that the numbers of α1 and α2 adrenoreceptor binding sites in the PVH are corticosterone-sensitive [41], and α1 adrenoreceptor mechanisms can regulate the intracellular signalling pathways involved with Crh expression [21].

Previous studies that have investigated the impact of catecholaminerigic afferents on CRH synthetic mechanisms in adrenal-intact unstressed animals have reported inconsistent results depending on which lesioning technique was used, and whether levels of CRH peptide or Crh expression were measured. Those using physical [28] or 6-hydroxydopamine lesions [26] of the ventral noradrenergic bundle (VNAB), or pharmacologically-mediated depletion of brain PNMT [27] all found a marked reduction of CRH in the PVH that correlated with the loss of DBH-ir or PNMT-ir respectively. In contrast, Swanson & Simmons [5] who, like Sawchenko [28] used VNAB lesions, and Ritter et al. [20], who used a PVH-targeted DSAP lesion, found no effects on CRH mRNA levels despite a marked depletion in DBH-ir in both studies. These latter results are consistent with our current findings. Ritter et al. [20] also reported no effects of the DSAP lesions on CRH peptide levels in the PVH. These discrepant findings likely reflect differences between lesion methodologies. Physical VNAB lesions are not specific to a particular neuronal phenotype and will ablate other ascending projections to the PVH that use the same trajectory as catecholamine neurones, while pharmacological lesions have recognised issues with chemical and/or target site specificity [30].

At this point it is worth noting that any catecholamine/glucocorticoid interactions that impact Crh expression most likely do not involve direct corticosterone-mediated GR actions on Crh. While Crh does contain non-classical glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) that can suppress transcription in transfected cells [42], the functional significance of any direct action of corticosterone on Crh in vivo remains unproven [reviewed in 6,12]. Of course, this does not negate the likelihood that CORT acts elsewhere in CRH neurons to regulate those processes that control Crh expression [43,44].

A second candidate mechanism derives from the fact that GRs are expressed by most hindbrain monoaminergic neurones [45], including many adrenergic neurones that project to the PVH [29]. This means that corticosterone can directly modulate the function of these catecholaminerigic neurones that project to the forebrain, perhaps in a manner that influences how they integrate information they receive from other sources. Signals associated with metabolism and energy status may be of particular importance because corticosterone has profound effects on long-term metabolic regulation. This also means that signals generated by corticosterone’s impact on metabolism may themselves interact with catecholaminergic neurons to control PVH function, as we have previously suggested [6]. This possibility is substantiated by the finding that increased sucrose, and thereby caloric intake in ADX animals intake mimics corticosterone’s effects on HPA variables, including the ability to reduce CRH mRNA [46]. These results support the idea that corticosterone and other metabolic signals exhibit at least some mechanistic commonalities in the way they interact with the HPA axis [46].

Corticosterone helps to mobilise fuels from energy stores in liver, adipose tissue, and muscle during negative energy balance, when its levels are increased [47]. Furthermore, the rate of normal body weight increase is suppressed if circulating corticosterone levels are moved either lower or higher than the narrow range found in adrenal intact animals [32]. These metabolic effects raise the possibility that corticosterone’s ability to suppress neuroendocrine CRH activity in the PVH in the absence of chronic stress is at least partly dependent on the way that signals associated with altered peripheral energy status, including corticosterone, are integrated by catecholaminergic neurones and then relayed to the hypothalamus. This idea is consistent with our results where we found significant difference in short-term changes in body weight (and to a lesser extent food intake) in the ADX Hi-Cort groups. Here DSAP lesions completely reversed the loss in body weight seen in the unlesioned animals, an effect that may involve a small increase in food intake. Adrenal-intact lesioned animals also showed increased body weight gains compared to the unlesioned group. Another study has reported that DSAP lesions increase body weight of adrenally intact animals [30], although here significant differences were not apparent for many weeks, which suggests the differences we see may be short-lived.

We already know that catecholaminergic inputs to the PVH and forebrain are essential for HPA and feeding responses when glucose homeostasis is compromised [20–22,30]. Our results now show that these same afferents only make significant contributions to corticosterone-mediated regulation of Crh and Avp when circulating corticosterone is either below or above the normal range for long periods. When circulating corticosterone is absent DSAP lesions suppress AVP hnRNA but not CRH mRNA. However, these lesions have no effect on the ability of plasma corticosterone to suppress Crh expression when it is at the levels found in intact animals. At corticosterone concentrations that are higher than the normal range, intact catecholaminergic afferents are required for corticosterone to suppress Crh expression. These results show that the mechanisms operating at very low corticosterone concentrations to suppress Crh expression are distinct from those operating at higher corticosterone concentrations, which are compromised by DSAP lesions. Our findings are also consistent with electrophysiological studies that show a significant impact of corticosterone on the catecholaminergic mechanisms that modulate GABAergic control of PVH neuroendocrine neuronal excitation [24,25]. Although these electrophysiological results have more bearing on peptide release mechanisms, the do emphasise the importance of catecholaminergic projections to glucocorticoid feedback in the PVH.

When taken together with those from other studies [20–23,30], our current findings show that catecholaminergic inputs to the PVH and forebrain are necessary to generate the adaptive responses that restore normal function when homeostatic variables move outside their normal range. We also show that these inputs become increasingly important for regulating the corticosterone sensitivity of CRH neurons as corticosterone concentrations increase. They also emphasise that the way corticosterone acts on CRH neurons at low and high levels is fundamentally different. Catecholaminergic inputs become less important when homeostatic variables remain within their normal ranges. For example, the changes in circulating corticosterone seen across the day are unaffected by DSAP lesions [20] as are CRH mRNA levels [20, present study]. Furthermore, given that catecholoaminergic afferents provide the PVH and other hypothalamic nuclei with neurally encoded information about metabolic status [20–22,30], it seems likely that the ability of corticosterone, as an essential metabolic hormone, to modulate how the PVH controls the HPA axis during long-term challenges to energy metabolism is mediated partly by way of its interactions with this important afferent set.

Together with previous studies [5,20–22,24–28], our results show that how CRH neuroendocrine neurons, glucocorticoids, and catecholaminergic neurones interact to control HPA function is highly complex. These interactions likely involve concentration-dependent effects on the multifaceted processes that control ACTH secretogogue gene transcription, mRNA translation, peptide maturation into bioactive peptide, and their eventual release into the hypophysial portal vasculature (see also [6,22]). In this regard, we have previously proposed that a glucocorticoid-sensitive switching mechanism determines how peptide gene expression in the CRH neurones responds to the differential activation of afferent inputs [6,48]. In this model, how glucocorticoids control the response of genes in the PVH to a particular stressor or metabolic challenge is dependent upon which set of afferents is activated at a particular time. It seems reasonable to propose that corticosterone’s interactions with catecholaminergic inputs to the hypothalamus forms part of this mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Graciela Sanchez-Watts for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant NS029728 (AGW).

References

- 1.Yates FE, Maran JW. Stimulation and inhibition of adrenocorticotropin release. In: Knobil E, Sawyer WH, editors. Handbook of Physiology, Vol IV Pt 2, The Pituitary and Its Neuroendocrine Control. Amer. Physiol. Soc; Washington, DC: 1974. pp. 367–404. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller-Wood ME, Dallman MF. Corticosteroid inhibition of ACTH secretion. Endocr Rev. 1984;5:1–24. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallman MF, Akana SF, Cascio CS, Darlington DN, Jacobson L, Levin N. Regulation of ACTH secretion: variations on a theme of B. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1987;43:113–73. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571143-2.50010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones MT, Gillham B. Factors involved in the regulation of adrenocorticotropic hormone/beta-lipotropic hormone. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:743–818. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.3.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson LW, Simmons DM. Differential steroid hormone and neural influences on peptide mRNA levels in CRH cells of the paraventricular nucleus: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:413–35. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts AG. Glucocorticoid regulation of peptide genes in neuroendocrine CRH neurons: a complexity beyond negative feedback. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26:109–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiss JZ, Mezey E, Skirboll L. Corticotropin-releasing factor-immunoreactive neurons of the paraventricular nucleus become vasopressin positive after adrenalectomy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1854–858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Vale WW. Co-expression of corticotropin-releasing factor and vasopressin immunoreactivity in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons of the adrenalectomized rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1883–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawchenko PE. Adrenalectomy-induced enhancement of CRF and vasopressin immunoreactivity in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons: anatomic, peptide, and steroid specificity. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1093–106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-04-01093.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makino S, Gold PW, Schulkin J. Corticosterone effects on corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA in the central nucleus of the amygdala and the parvocellular region of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res. 1994;640:105–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G. Region-specific regulation of neuropeptide mRNAs in rat limbic forebrain neurones by aldosterone and corticosterone. J Physiol. 1995;484:721–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguilera G, Liu Y. The molecular physiology of CRH neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:67–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McEwen BS, Weiss JM, Schwartz LS. Uptake of corticosterone by rat brain and its concentration by certain limbic structures. Brain Res. 1969;16:227–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(69)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronsson M, Fuxe K, Dong Y, Agnati LF, Okret S, Gustafsson JA. Localization of glucocorticoid receptor mRNA in the male rat brain by in situ hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9331–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman JP, Cullinan WE, Watson SJ. Involvement of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in tonic regulation of paraventricular hypothalamic CRH and AVP mRNA expression. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:433–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman JP, Cullinan WE, Morano MI, Akil H, Watson SJ. Contribution of the ventral subiculum to inhibitory regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenocortical axis. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:475–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Bérod A, Hartman BK, Helle KB, Vanorden DE. An immunohistochemical study of the organization of catecholaminergic cells and terminal fields in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1981;196:271–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham ET, Jr, Sawchenko PE. Anatomical specificity of noradrenergic inputs to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the rat hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1988;274:60–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.902740107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritter S, Watts AG, Dinh TT, Sanchez-Watts G, Pedrow C. Immunotoxin lesion of hypothalamically projecting norepinephrine and epinephrine neurons differentially affects circadian and stressor-stimulated corticosterone secretion. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1357–67. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan AM, Ponzio TA, Sanchez-Watts G, Stanley BG, Hatton GI, Watts AG. Catecholaminergic control of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in paraventricular neuroendocrine neurons in vivo and in vitro: a proposed role during glycemic challenges. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7344–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0873-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan AM, Kaminski KL, Sanchez-Watts G, Ponzio TA, Kuzmiski JB, Bains JS, Watts AG. MAP kinases couple hindbrain-derived catecholamine signals to hypothalamic adrenocortical control mechanisms during glycemia-related challenges. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18479–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4785-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinh TT, Flynn FW, Ritter S. Hypotensive hypovolemia and hypoglycemia activate different hindbrain catecholamine neurons with projections to the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R870–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00094.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang JH, Li LH, Lee S, Jo IH, Lee SY, Ryu PD. Effects of adrenalectomy on the excitability of neurosecretory parvocellular neurones in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:293–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang JH, Li LH, Shin SY, Lee S, Lee SY, Han SK, Ryu PD. Adrenalectomy potentiates noradrenergic suppression of GABAergic transmission in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons of hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:514–23. doi: 10.1152/jn.00568.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso G, Szafarczyk A, Balmefrézol M, Assenmacher I. Immunocytochemical evidence for stimulatory control by the ventral noradrenergic bundle of parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus secreting corticotropin releasing hormone and vasopressin in rats. Brain Res. 1986;397:297–307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mezey E, Kiss JZ, Skirboll LR, Goldstein M, Axelrod J. Increase of corticotropin-releasing factor staining in rat paraventricular nucleus neurones by depletion of hypothalamic adrenaline. Nature. 1984;310:140–1. doi: 10.1038/310140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawchenko PE. Effects of catecholamine-depleting medullary knife cuts on corticotropin-releasing factor and vasopressin immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus of normal and steroid-manipulated rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1988;48:459–70. doi: 10.1159/000125050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawchenko PE, Bohn MC. Glucocorticoid receptor-immunoreactivity in C1, C2, and C3 adrenergic neurons that project to the hypothalamus or to the spinal cord in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:107–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritter S, Bugarith K, Dinh TT. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholamine subgroups produces selective impairment of glucoregulatory responses and neuronal activation. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432:197–216. doi: 10.1002/cne.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watts AG, Tanimura S, Sanchez-Watts G. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin gene transcription in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of unstressed rats: daily rhythms and their interactions with corticosterone. Endocrinology. 2004;145:529–40. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akana SF, Cascio CS, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Corticosterone: narrow range required for normal body and thymus weight and ACTH. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:R527–32. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.249.5.R527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swanson LW. Brain Maps: Structure of the Rat Brain. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banihashemi L, Rinaman L. Noradrenergic inputs to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus underlie hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis but not hypophagic or conditioned avoidance responses to systemic yohimbine. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11442–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3561-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovács KJ, Földes A, Sawchenko PE. Glucocorticoid negative feedback selectively targets vasopressin transcription in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3843–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03843.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarabdjitsingh RA, Conway-Campbell BL, Leggett JD, Waite EJ, Meijer OC, de Kloet ER, Lightman SL. Stress responsiveness varies over the ultradian glucocorticoid cycle in a brain-region-specific manner. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5369–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Itoi K, Helmreich DL, Lopez-Figueroa MO, Watson SJ. Differential regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone and vasopressin gene transcription in the hypothalamus by norepinephrine. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5464–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05464.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datson NA, Morsink MC, Meijer OC, de Kloet ER. Central corticosteroid actions: Search for gene targets. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:272–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E, Oitzl MS, Joëls M. Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:269–301. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Revs. 2000;21:55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Leibowitz SF. Impact of circulating corticosterone on alpha 1- and alpha 2-noradrenergic receptors in discrete brain areas. Brain Res. 1986;368:404–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King BR, Smith R, Nicholson RC. Novel glucocorticoid and cAMP interactions on the CRH gene promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;194:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bali B, Ferenczi S, Kovács KJ. Direct inhibitory effect of glucocorticoids on corticotrophin-releasing hormone gene expression in neurones of the paraventricular nucleus in rat hypothalamic organotypic cultures. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:1045–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiser MJ, Osterlund C, Spencer RL. Inhibitory effects of corticosterone in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) on stress-induced adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion and gene expression in the PVN and anterior pituitary. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:1231–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Härfstrand A, Fuxe K, Cintra A, Agnati LF, Zini I, Wikström AC, Okret S, Yu ZY, Goldstein M, Steinbusch H, Verhofstad A, Gustafsson J-A. Glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivity in monoaminergic neurons of rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9779–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laugero KD, Bell ME, Bhatnagar S, Soriano L, Dallman MF. Sucrose ingestion normalizes central expression of corticotropin-releasing-factor messenger ribonucleic acid and energy balance in adrenalectomized rats: a glucocorticoid-metabolic-brain axis? Endocrinology. 2001;142:2796–804. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dallman MF, Strack AM, Akana SF, Bradbury MJ, Hanson ES, Scribner KA, Smith M. Feast and famine: critical role of glucocorticoids with insulin in daily energy flow. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1993;14:303–47. doi: 10.1006/frne.1993.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G. Interactions between heterotypic stressors and corticosterone reveal integrative mechanisms for controlling corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in the rat paraventricular nucleus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6282–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]