Abstract

Objectives

Few longitudinal studies have studied the influence of the care environment on the clinical progression of dementia. We examined whether caregiver coping strategies predict dementia progression in a population-based sample.

Design

Longitudinal, prospective cohort study

Setting

Cache County (Utah) Population

Participants

226 persons with dementia, and their caregivers, assessed semi-annually for up to 6 years.

Measurements

Ways of Coping Checklist-Revised, Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).

Results

Mean (SD) age of dementia onset was 82.11 (5.84) and mean caregiver age was 67.41 (13.95). Mean (SD) follow-up was 1.65 (1.63) years from baseline. In univariate linear mixed effects models, increasing use of problem-focused and counting blessings by caregivers was associated with slower patient worsening on the MMSE. Problem-focused coping, seeking social support, and wishful thinking were associated with slower CDR-SB worsening. Considering covariates, increasing use of problem-focused coping was associated with 0.70 points per year less worsening on the MMSE and 0.55 point per year less worsening on the CDR-sb. Compared to no use, “regular” use of this strategy was associated with a 2-point per year slower worsening on the MMSE and 1.65-point per year slower worsening on the CDR-sb.

Conclusions

Caregiver coping strategies are associated with slower dementia progression. Developing interventions that target these strategies may benefit dementia patients.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, caregiver coping, stress coping, problem focused coping, dementia caregiving, dementia progression, cognitive decline, functional decline

OBJECTIVE

Dementia is characterized by progressive cognitive and functional decline. Even in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) widely varying rates of decline occur, for example, between 0.8 to 4.4 points in annual rate of change (ARC) on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) (1). In the population-based Cache County Study, we reported an ARC of 1.53 on the MMSE, and 1.82 on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of boxes (CDR-sb). Significant heterogeneity characterized rates of progression, with approximately 30 – 58% of persons progressing slowly (less than one point per year) over a period of five to seven years after AD onset (2).

There is insufficient information on factors that affect rates of progression in AD or other dementias. Most studied have been the effects of the apolipoprotein E gene (3), medical conditions (4),(5), medications (6) and nutritional supplements (7). There are conflicting findings for APOE and vascular medical conditions, with some effects varying by patient characteristics (8). Antihypertensive medications (9), lipid lowering agents (9), and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (8) have been associated with slower progression in AD. Beneficial effects of nutritional supplements on progression have been reported by some (10) but not other studies (11). Although some of the above findings may lead to effective interventions, enthusiasm is diminished by potential unwanted side effects, especially with respect to medications.

Arguably, one of the most significant factors influencing the life of a dementia patient is the care environment. There is evidence that caregiving approaches and care management strategies can modify the environment to reduce behavioral disturbances in the person with dementia (12). In addition, caregiver characteristics are associated with outcomes related to institutionalization of the dementia patient (13). Worse caregiver health and greater burden have predicted institutionalization (14). In other studies having a non-spouse caregiver (15) and family dysfunction (16) predicted earlier institutionalization whereas positive spousal interactions and high caregiver commitment delayed institutionalization (17). Closer caregiver relationships have been associated with better adjustment to nursing home placement in dementia patients (18).

Few studies have examined how caregiver characteristics affect the rate of dementia progression. We previously reported that closer caregiver-patient relationships predicted slower cognitive and functional decline in our population-based sample of persons with AD. In that analysis, patients with spousal caregivers declined more slowly, but there was also a clear effect for caregiver relationship closeness. The magnitude of the effect was similar to that reported for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (19). Others have found closer caregiver relationships to predict better psychological well being and problem solving abilities in dementia patients (20).

Caregiver coping is another factor that may influence outcomes in dementia. In the stress and coping model of Folkman and Lazarus, instrumental coping strategies such as problem-focused coping are used to manage the source of stress, whereas emotion-focused strategies are used to regulate distress (21). A modification to the original model posits a “meaning focused” strategy that is used to sustain motivation to further employ coping resources after a failed resolution. This strategy draws upon personal values, including spiritual, religious or existential beliefs (22). Coping strategies may also be conceptualized as an active-cognitive (e.g., reframing the problem or looking at the positive side), active-behavioral (e.g., problem-focused, seeking support), or avoidance (e.g., ignoring the problem) strategies (23). Approaches that are active-cognitive, active-behavioral, problem solving, as well as seeking help, communicating feelings, and drawing strength from adversity reportedly are associated with fewer negative emotional states, whereas avoidance, blaming self, and escape are associated with more negative emotions (23). Similar findings have been reported among caregivers of persons with AD. For example, greater use of strategies such as avoidance, denial, and self-blame are associated with depression or anxiety in response to the stress of caregiving (24–27). This has also been demonstrated longitudinally (27–28).

Very little research has been conducted on caregiver coping strategies in relation to outcomes of persons with dementia. One study, drawing from a research registry of persons with AD, examined caregiver depression and coping strategies as potential predictors of survival in care recipients. While neither instrumental nor acceptance coping was associated with patient survival, “wishfulness-intrapsychic” coping was associated with shorter survival of persons with AD. The authors hypothesized that engaging in such strategies (such as fantasy, daydreaming), may result in caregivers being less psychologically involved in the situation and less able to engage in person-centered care. Alternative explanations raised were possible associations of “wishfulness-intrapsychic” coping with caregiver personality (e.g., neuroticism) or institutional care (29). Another study found that a training program to enhance coping skills and reduce distress was associated with longer survival in the dementia patient (30).

We know of no studies that have examined whether caregiver coping strategies influence the rate of cognitive and functional decline in dementia. We examined this question in a longitudinal, population-based study of factors that influence dementia progression, the Cache County Dementia Progression Study (DPS). We hypothesized that dementia patients whose caregivers relied more on dysfunctional coping strategies (e.g, avoidant and blaming) would show faster decline on cognitive and functional measures, whereas those whose caregivers relied more on problem-focused strategies would show slower rates of decline.

METHODS

Originating from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging (CCSMA), DPS is an ongoing, longitudinal population-based study of persons with incident dementia (diagnosed within a few years of onset) and their caregivers (2). DPS has conducted semi-annual follow-ups of dementia patient and caregiver dyads, examining genetic and environmental factors that influence the clinical progression of dementia in cognition, function and behavior.

Dementia Ascertainment and Diagnosis

In its first wave, CCSMA enrolled 90% of the 5657 Cache County residents age 65 and older. Four triennial waves of case detection have been completed, the methods of which have been reported elsewhere (31). Briefly, participants were screened for cognitive impairment with a revision of the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam(32). Those who screened positive, as well as members of a weighted, stratified population subsample were studied further using an informant-based telephone interview that queried cognitive and functional impairments typical in dementia. Participants whose interviews were suggestive of dementia or its prodrome, and those of the population subsample, were invited to undergo a clinical assessment (CA) by a trained research nurse and psychometric technician. The CA included a structured physical and neurological examination and a battery of neuropsychological tests with a knowledgeable informant providing information regarding the participant’s history of cognitive or functional impairment, medical history, and psychiatric symptoms.

A geropsychiatrist and neuropsychologist next reviewed data from the CA and assigned preliminary diagnoses of dementia according to DSM-III-R criteria (33). An age of onset was estimated as the age when the participant unambiguously met DSM-III-R criteria for dementia. Participants with suspected dementia were asked to undergo neuroimaging and laboratory studies as well as a geropsychiatrist’s exam to provide differential diagnoses of dementia. A panel of experts in neurology, geropsychiatry, neuropsychology, and cognitive neuroscience reviewed all available clinical data and assigned diagnoses of AD and other forms of dementia according to standard protocols [e.g., NINCDS-ADRDA research criteria for AD (34)]. All with suspected dementia or a suspected dementia prodrome were invited for an 18-month follow-up CA, the results of which were reviewed by the expert panel who rendered final diagnoses. Participants with dementia newly diagnosed at Waves 2–4, and their caregivers were invited to join the DPS.

Procedures of DPS

As previously reported (2), (19), dementia participants and their caregivers were visited semi-annually by a research nurse and a psychometric technician. Participants with dementia completed cognitive testing. Interviews with caregivers provided information regarding the dementia participants’ current medical conditions, medications, nutritional intake, functional impairment, neuropsychiatric symptoms and daily activities. Caregivers also reported on their own medical and psychiatric status, and completed a questionnaire of coping strategies (see below). To be eligible for the current analyses, dementia participants must not have been living in a nursing home at baseline and must have had a consistent caregiver over the course of the study who participated in the coping assessment. Participant assent and caregiver informed consent were obtained at each visit. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Utah State and the Johns Hopkins Universities.

Measures of Dementia Progression

The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), is a global measure of cognition assessing orientation, attention, memory, language, and visuospatial ability (35), where higher point totals are associated with better performance. The test was administered by trained neuropsychological technicians. As previously reported (31), we calculated an adjusted score by discarding items missed because of sensory or motor impairment (e.g., severe vision or hearing loss, motor weakness, tremor, etc.), noting the percent correct, and rescaling the final score on a 30-point scale. Such adjustments were made only up to 10% of the total score (3 points).

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR (36)) is a measure of functional ability in six areas: memory, orientation, judgment/problem solving, community affairs, participation in home/hobbies, and personal care. An ordinal scale is used to reflect degree of impairment: 0 = no impairment; 0.5 = questionable impairment; 1 = mild impairment; 2 = moderate impairment; 3 = severe impairment; 4 = profound impairment; 5 = terminal. Under the supervision of a study geropsychiatrist or neuropsychologist, a trained research nurse scored the CDR at each visit. The ratings in each category (“box”) were summed to produce the “sum of boxes” (CDR-sb).

Predictors of Dementia Progression: Ways of Coping Checklist-Revised

Caregiver coping strategies were assessed annually with the Ways of Coping Checklist-Revised (37). This 57-item questionnaire asked respondents to think of a problem and how frequently (never, rarely, sometimes, or regularly) they used various coping behaviors. Scores on eight scales representing the following coping strategies were obtained: Problem-Focused, Seeks Social Support, Avoidance, Wishful Thinking, Blames Self, Blames Others, Counts Blessings, and Religious coping. To preserve the original scale of measurement, we calculated mean scores for each scale based on all items within the scale. Because of the good internal consistency of scale items (37), we addressed missing items by imputing the mean value of the remaining items of each scale for up to 10% of the items. Scales where more than 10% of items were missing were excluded from analyses. Across all caregivers, items and visits, less than 3% of item scores were imputed.

Covariates: Caregiver and Dementia Patient Factors

A number of caregiver sociodemographic factors that may potentially affect the association between caregiver coping and patient decline were tested as covariates. These included caregiver gender and education as well as the kin relationship to patient. Covariates also included age of dementia onset and duration of dementia at baseline.

Analyses

We summarized sample characteristics with descriptive statistics. Differences between participants with complete versus incomplete coping data were examined using chi-square tests for categorical and analysis of variance for continuous variables. To evaluate the association between caregiver coping strategies and cognitive (MMSE) or functional (CDR-sb) progression in dementia, we used linear mixed effects models, treating subject-specific intercepts and linear change with time as random effects. This approach allowed us to account for the dependence between repeated measures within subjects. In exploratory work, we examined the stability of coping strategies over time and estimated correlations among the strategies to check for collinearity. For each outcome, we estimated univariate linear mixed models for each coping strategy. Next, starting with those demonstrating the highest associations with each outcome, we systematically added each coping strategy and covariates, retaining only those that were the strongest predictors of the outcome based on two tailed tests, while providing the best model fit as determined by likelihood ratio tests for nested models. Coping strategies were treated as a time-varying variable, whereas covariates were treated as fixed factors. Statistical analyses for the MMSE and CDR-sb used SPSS software (Version 18).

RESULTS

Two hundred twenty-six (75%) of caregiver and dementia participant dyads had coping data. As displayed in Table 1, caregivers lacking coping data were more often male [X2 (df, 1) = 3.68, p = 0.055], whose care recipients had significantly fewer [t (df, 175) = 5.11, p < 0.001)] and shorter duration of follow-ups [t (df,134) = 4.26, p < 0.001)]. Other caregiver and dementia participant characteristics did not differ between groups. Mean (SD) number and duration of follow-ups for those with coping data were 3.49 (2.49) and 1.65 (1.63) years, respectively. Forty-six (20%) of the 226 dementia participants lacking follow-ups were significantly older [M (SD) = 85.17 (6.56) versus 81.33 (5.39); t (df, 226) = 4.13, p <0.001], with worse baseline MMSE [M (SD) = 18.46 (7.09) versus 22.29 (5.07); t (df, 56) = 3.83, p = 0.001] and CDR-sb [M (SD) = 7.90 (5.07) versus 5.71 (3.40); t (df, 54) = 3.47, p = 0.008]. There was no difference in education and dementia duration at baseline from those with follow-ups. The most frequently employed coping strategies by caregivers were counts blessings, followed by problem-focused, and religious coping.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Coping Data | Missing Coping Data | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 226 | N = 77 | |

| Caregiver | ||

| Female, N (%) | 182 (79.8) | 46 (68.7)* |

| Age, M (SD) | 67.41 (13.95) | 71.14 (14.38) |

| Education, M (SD) | 14.12 (2.33) | 13.97 (2.26) |

| Relationship to patient, N (%) | ||

| --Spouse | 99 (43.4) | 33 (42.9) |

| --Adult Child | 112 (49.1) | 26 (40.6) |

| --Other | 17 (7.5) | 5 (7.8) |

| Baseline Frequency of Contact, N (%) | ||

| --Co-reside | 120 (56.1) | 43 (67.2) |

| --Daily | 29 (13.6) | 5 (7.8) |

| --Less than Daily | 65 (30.4) | 16 (25.0) |

| Coping strategies at baseline, M (SD)† | ||

| --Problem-focused | 1.99 (0.53) | |

| --Seeks social support | 1.69 (0.71) | |

| --Avoidance | 1.20 (0.55) | |

| --Blames self | 1.22 (0.85) | |

| --Blames others | 0.88 (0.72) | |

| --Counts blessings | 2.27 (0.54) | |

| --Religious | 1.78 (0.66) | |

| --Wishful thinking | 1.47 (0.68) | |

| Patient | ||

| AD Dementia, N (%) | 167 (73.3) | 48 (69.5) |

| Vascular Dementia, N (%) | 29 (12.7) | 8 (11.6) |

| Other Dementia, N (%) | 32 (14.0) | 13 (18.8) |

| Female, N(%) | 123 (53.9) | 40 (51.9) |

| Age of dementia onset, M (SD) | 82.11 (5.84) | 83.25 (6.01) |

| Education, M (SD) | 13.40 (2.75) | 13.18 (3.38) |

| Dementia duration at baseline, M (SD) | 3.42 (1.87) | 3.55 (1.87) |

| Baseline MMSE, M (SD) | 21.49 (5.74) | 20.39 (6.89) |

| Baseline Global CDR, M (SD) | 1.29 (0.64) | 1.36 (0.78) |

| Fair or Poor Health at Baseline, N (%) | 38 (16.7) | 15 (22.7) |

| Number of follow-ups, M (SD) | 3.49 (2.49) | 1.91 (1.85)** |

| Duration of follow-ups in yrs, M (SD) | 1.65 (1.63) | 0.82 (1.34)** |

values range from 0 (never) to 3 (regularly);

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Correlations among coping strategies; stability of strategies over time

Zero order correlations at baseline revealed significant correlations between problem-focused coping and the other seven strategies, with seeks social support [r (df, 180) = .58, p < 0.001] and counts blessings [r (df, 180) = .51, p < 0.001] being highest. Also moderately correlated were avoidance with blames self [r (df, 162) = .63, p < 0.001], blames others [r (df, 168) = .53, p < 0.001], or wishful thinking [r (df, 177) = .69, p <0.001], and blames self with wishful thinking [r (df, 164) = .50, p < 0.001].

Individual linear mixed models suggested relative stability in the use of each coping strategy over time. This was true for problem-focused, wishful thinking, and blames others. A subgroup of caregivers showed slight change in use of coping strategies: spouse caregivers reported increasing use of seeks social support [t (df, 60.75) = 1.69, p = 0.096] whereas adult children reported increasing use of avoidance [t (df, 3.2) = 3.08, p = 0.05] and blames self [t (df, 70.42) = 2.40, p = 0.019] over time. Models with counts blessings and religious coping did not converge to achieve a reliable solution.

Individual coping strategies and dementia progression

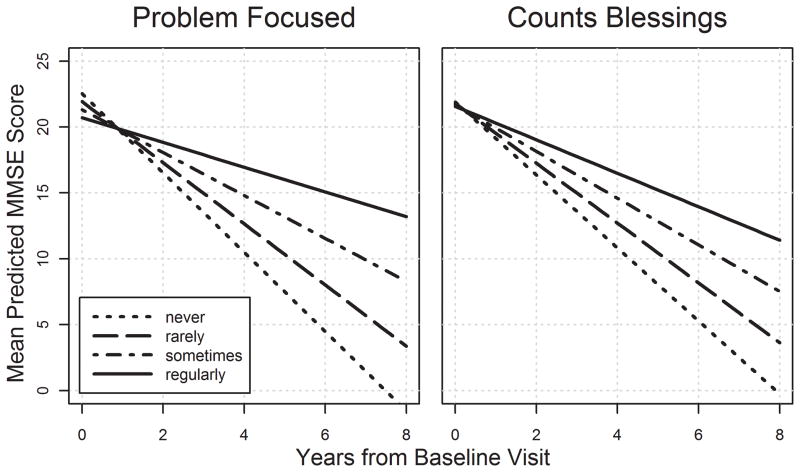

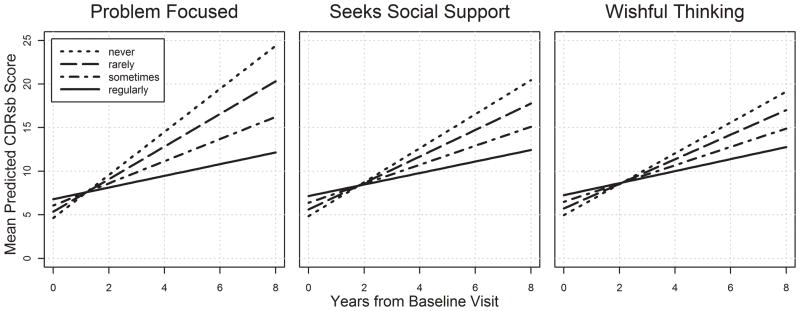

As displayed in Tables 2 and 3, more frequent use of problem-focused coping and counts blessings by caregivers was associated with slower cognitive decline in dementia participants. Problem-focused coping, seeks social support, and wishful thinking were each associated with slower functional decline. Figures 1 and 2 display the relationship between caregiver coping strategies and cognitive and functional decline among patients with dementia.

Table 2.

Mixed Models of Caregiver Strategies for MMSE

| Problem Focused | Counts Blessings | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | |

| Intercept | 22.54 (1.17) | 274.69 | 19.28 | 20.24, 24.84 | <0.001 | 21.90 (1.22) | 341.04 | 17.97 | 19.50, 24.29 | <0.001 |

| Time | −3.01 (0.73) | 156.49 | −4.13 | −4.45, −1.57 | <0.001 | −2.77 (0.69) | 244.26 | −4.03 | −4.12, −1.42 | <0.001 |

| Coping | −0.61 (0.55) | 248.87 | −1.11 | −1.70, 0.48 | 0.270 | −0.21 (0.51) | 319.53 | −0.42 | −1.22, 0.79 | 0.676 |

| Time × Coping | 0.69 (0.36) | 163.63 | 1.93 | −0.018, 1.40 | 0.056 | 0.50 (0.29) | 244.18 | 1.76 | −0.06, 1.07 | 0.079 |

Est. = parameter estimates of the average difference in MMSE scores.

Table 3.

Mixed Models of Caregiver Strategies for CDR-sb

| Problem Focused | Seeks Social Support | Wishful Thinking | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | |

| Intercept | 4.63 (0.92) | 272.12 | 5.03 | 2.82, 6.44 | <0.001 | 4.84 (0.59) | 324.74 | 8.20 | 3.68, 6.00 | <0.001 | 4.97 (0.55) | 313.48 | 9.08 | 3.89, 6.05 | <0.001 |

| Time | 2.47 (0.64) | 189.08 | 3.84 | 1.20, 3.73 | <0.001 | 1.95 (0.37) | 223.83 | 5.26 | 1.22, 2.68 | <0.001 | 1.77 (0.33) | 222.12 | 5.36 | 1.12, 2.41 | <0.001 |

| Coping | 0.72 (0.44) | 265.34 | 1.63 | −0.15, 1.59 | 0.103 | 0.77 (0.32) | 321.44 | 2.43 | 0.15, 1.40 | 0.016 | 0.76 (0.34) | 309.21 | 2.27 | 0.10, 1.42 | 0.024 |

| Time × Coping | −0.60 (0.32) | 201.52 | −1.90 | −1.22, 0.02 | 0.059 | −0.43 (0.20) | 257.97 | −2.11 | −0.83, −0.03 | 0.035 | −0.36 (0.20) | 246.00 | −1.82 | −0.75, 0.03 | 0.071 |

Est. = parameter estimates of the average difference in CDR-sb score.

Figure 1.

Caregiver coping strategies and rate of MMSE decline in dementia. Plots are based on univariate models. Models with covariates found only significant effects for problem focused coping, with effect sizes similar in magnitude to those in the univariate analyses.

Figure 2.

Caregiver coping strategies and rate of functional worsening in dementia. Plots are based on univariate analyses. Models with covariates found only significant effects for problem focused coping, with effect sizes similar in magnitude to those in the univariate analyses.

Caregiver coping strategies and dementia progression: models with covariates

We tested the following covariates in mixed effects models examining the association between coping strategies and dementia progression: patient age at dementia onset, dementia duration, kin relationship to person with dementia, and caregiver education and gender. Due to multicollinearity, we did not simultaneously test both caregiver kin relationship and age in the models. As displayed in Table 4, only problem-focused coping by caregivers was associated with slower cognitive and functional decline in dementia participants. Each one-unit increase in frequency of use of this strategy was associated with a 0.70 point per year slower worsening on the MMSE and approximately 0.5 point per year slower worsening on the CDR-sb. Compared to those who never used a problem-focused strategy, this effect corresponds to a 1.4 point per year slower worsening on the MMSE for those who “sometimes” used the strategy (Cohen’s d of −2.67) and a 2.1 point per year slower worsening for those who “regularly” used the strategy (Cohen’s d of −2.74), the latter corresponding to a 37% reduction in average ARC for participants with AD in this sample. For the CDR-sb, the reduction in rate of progression was 1.10 points per year (Cohen’s d of 2.40) and 1.65 points per year (Cohen’s d of 2.46) for those who “sometimes” and “regularly” used problem-focused strategies, respectively. Values exceeding a Cohen’s d of 0.80 are considered large effects (38).

Table 4.

Mixed effect models with covariates

| MMSE | CDR-sb | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | Est. (SE) | df | t | 95% CI | P | ||

| Intercept | 26.71 (1.28) | 307.25 | 20.84 | 24.19, 29.23 | <0.001 | 3.25 (1.06) | 311.64 | 3.06 | 1.16, 5.33 | 0.002 | |

| Time | −3.02 (0.72) | 158.98 | −4.22 | −4.43, −1.60 | <0.001 | 2.36 (0.63) | 191.24 | 3.74 | 1.11, 3.60 | <0.001 | |

| Problem Focused | −0.52 (0.53) | 250.92 | −1.00 | −1.56, 0.51 | 0.321 | 0.38 (0.43) | 268.44 | 0.90 | −0.46, 1.23 | 0.371 | |

| Problem Focused × Time | 0.70 (0.35) | 166.01 | 1.98 | 0.001, 1.39 | 0.05 | −0.55 (0.31) | 205.37 | −1.78 | −1.16, 0.06 | 0.077 | |

| Dementia duration | −1.28 (0.20) | 215.44 | −6.40 | −1.67, −0.89 | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.13) | 217.19 | 5.94 | 0.51, 1.02 | <0.001 | |

| CG relationship | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | −1.30 (0.51) | 232.44 | −2.56 | −2.31, −0.30 | 0.011 |

| Spouse | |||||||||||

| Other | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 0.16 (0.92) | 211.97 | 0.18 | −1.64, 1.96 | 0.858 |

Reference is adult child. Est. = parameter estimates of the average difference in MMSE or CDR-sb score, adjusted for all terms in the model. In all models, the following covariates were tested: caregiver relationship, education, and gender, and patient dementia onset age and duration. Only significant covariates retained in the models are displayed in the table.

In a preliminary examination of potential moderators of the above associations, we found co-residence to be a significant moderator for rate of cognitive (LR X2 = 80.62, df = 4, p < 0.001) and functional decline (LR X2 = 31.99, df = 4, p < 0.001). The association between problem focused coping and dementia progression was more pronounced among dementia patients who did not reside with their caregivers [MMSE: t (df, 212.58) = 2.41, p = 0.017), CDR-sb: t (df, 242.91) = 4.41, p < 0.001].

DISCUSSION

In this population-based sample, regular use of problem-focused coping by caregivers was associated with notably slower decline in both cognition and function, a finding that considers the potential influence of environmental factors on dementia progression. Problem focused coping consists of seeking solutions coupled with formulating and implementing a plan of action to address the source of a problem (37), (22). Problem situations commonly occur over the course of dementia in which a problem-focused approach may be beneficial [e.g., a sudden decline prompting a visit to the physician, or sudden onset of agitation requiring modification of environmental triggers (39)]. This approach also encompasses processes that appear to foster acceptance (e.g., “accepted the next best thing to what I wanted,” or “changed or grew as a person in a good way”). The latter has been associated with more positive outcomes among AD caregivers (28). Additionally, coping strategies that foster personal growth as these items imply may help caregivers experience meaning in their roles and help renew their resources to continue to cope with challenges presented by the care recipient’s condition (22),(40).

While the current analysis does not examine specific caregiver activities or care management strategies associated with a problem-focused strategy, we speculate that the established effectiveness of problem-focused coping (41), and the diminished expressed-emotion that accompanies it leads to more effective caring and lowers emotional distress in the caregiver (23), (26), (28). Future research that examines caregiver depression and anxiety in relation to caregiver use of this coping strategy on the rate of cognitive and functional decline would test this hypothesis. The use of caregiver problem-focused coping may also lead to a more stimulating care environment and the use of strategies to improve patient nutrition and maintain good physical health, the latter of which has been associated with slower dementia progression (8),(9).

It is interesting to note that other “positive” coping strategies such as seek social support and counts blessings or “negative” strategies such as avoidance, blaming self or others and wishful thinking were not independent contributors to the rate of cognitive or functional decline in dementia. Correlations among coping strategies indicated that persons who employed problem-focused coping were also likely to employ others, including some that are not always adaptive. Future work in this area will consider the correlated nature of the coping strategies examined here, and whether a combination of strategies represented by latent variables may better predict more positive patient as well as caregiver outcomes.

Although our results cannot speak to the direction of effects (whether coping strategies affect patient outcomes or vice versa), they add to our previous findings that environmental factors such as a cognitively stimulating environment in early dementia (42) and closer caregiver-care recipient relationships predict slower declines in cognition and function (19). They raise the possibility of beneficial effects of dementia care interventions that improve the participation of the dementia patient in activities and caregiver-targeted interventions that strengthen feelings of closeness and improve use of problem-focused coping.

Several study limitations warrant discussion. We lacked the ability to examine coping strategies by problem, although some have reported no difference in strategies employed by specific problem types (37). Also, we lacked information on how caregivers perceived or appraised problems associated with caregiving, a potentially important factor that may influence both caregiver and patient outcomes. Our limited sample size did not permit an examination of coping strategies by type of dementia or potential factors such as dementia severity, neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver factors that may mediate or moderate the association between caregiver coping and dementia progression. Coping data were also missing on approximately 25% of the sample, most being male caregivers. Finally, the results were obtained in a sample made up primarily of Caucasian individuals from a single geographic area, and therefore, may not generalize to individuals from more diverse populations.

The study strengths include its population-based sample of persons with dementia and their caregivers, longitudinal design with assessment of eight separate coping strategies at each visit, follow-ups starting relatively early in the course of dementia, high follow-up rates with attrition mostly attributable to death, examination of both cognitive and functional outcomes in dementia, and examination of multiple caregiver demographic factors.

In summary, we report significant associations between caregiver coping strategies and the rate of cognitive and functional decline in dementia. Coupled with earlier findings from DPS, this result raises a potential role for caregiver and environmental factors in promoting higher functioning among persons with dementia.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants: R01AG21136, R01AG11380

•Grant support (research or CME)

NIMH, NIA, Associated Jewish Federation of Baltimore, Weinberg Foundation, Forest, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Eisai, Pfizer, Astra-Zeneca, Lilly, Ortho-McNeil, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, National Football League, Elan

•Consultant/Advisor

Astra-Zeneca, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Eisai, Novartis, Forest, Supernus, Adlyfe, Takeda, Wyeth, Lundbeck, Merz, Lilly, Pfizer, Genentech, Elan, NFL Players Association, NFL Benefits Office

•Honorarium or travel support

Pfizer, Forest, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Health Monitor

The authors are indebted to Dr. Ronald Munger for his unqualified support of the DPS. We also acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals whose activities have helped to ensure the success of the project: John C.S. Breitner, M.D., M.P.H., Cara Brewer, B.A., Tony Calvert, R.N., B.A., Michelle Carlson, Ph.D., Kimberly Graham, B.A., Robert C. Green, M.D., M.P.H., Hochang Ben Lee, M.D., Jeanne-Marie Leoutsakos, Ph.D., Carol Leslie, M.S., Lawrence S. Mayer, Ph.D., Michelle M. Mielke, Ph.D.,Chiadi U. Onyike, M.D., Roxane Pfister, M.S., Georgiann Sanborn, M.S., Nancy Sassano, Ph.D., Sarah Schwartz, M.S, Ingmar Skoog, M.D., Martin Steinberg, M.D., Katherine Treiber, Ph.D., Yorghos Tripodis, Ph.D., Kathleen A. Welsh-Bohmer, Ph.D., Heidi Wengreen, Ph.D.,RD, James Wyatt, and Peter P. Zandi, Ph.D., M.P.H. Finally, we thank the participants and their families for their participation and support.

Footnotes

Presented in preliminary form at the International Conference on Alzheimer Disease, Honolulu, HI, 2010

Author Disclosures: Peter V. Rabins, M.D., MPH

Legal testimony for Janssen Pharmaceutica

Constantine Lyketsos, M.D., MHS

JoAnn Tschanz, Kathleen Piercy, Chris Corcoran, Elizabeth Fauth, Maria Norton, Brian Tschanz, M. Scott Deberard, Christine Snyder, Courtney Smith and Lester Lee have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Behl P, Stefurak TL, Black SE. Progress in clinical neurosciences: cognitive markers of progression in Alzheimer’s disease. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. 2005;32:140–151. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100003917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, Schwartz S, et al. Progression of Cognitive, Functional and Neuropsychiatric Symptom Domains in a Population Cohort with Alzheimer’s Dementia The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:532–542. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faec23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyt BD, Massman PJ, Schatschneider C, et al. Individual growth curve analysis of APOE epsilon 4-associated cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2005;62:454–459. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalaria RN. The role of cerebral ischemia in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2000;21:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellew KM, Pigeon JG, Stang PE, et al. Hypertension and the rate of cognitive decline in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2004;18:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacabelos R. Pharmacogenomics and therapeutic prospects in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2005;6:1967–1987. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.12.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1216–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mielke MM, Rosenberg PB, Tschanz J, et al. Vascular factors predict rate of progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69:1850–1858. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000279520.59792.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Tschanz J, et al. Effects of cardiovascular medications on rate of functional decline in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:883–892. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318181276a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia. North American EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278:1327–1332. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.16.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dongen MC, van Rossum E, Kessels AG, et al. The efficacy of ginkgo for elderly people with dementia and age-associated memory impairment: new results of a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1183–1194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, et al. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1996–2021. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buhr GT, Kuchibhatla M, Clipp EC. Caregivers’ reasons for nursing home placement: clues for improving discussions with families prior to the transition. Gerontologist. 2006;46:52–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pot AM, Deeg DJ, Knipscheer CP. Institutionalization of demented elderly: the role of caregiver characteristics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:273–280. doi: 10.1002/gps.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitznagel MB, Tremont G, Davis JD, et al. Psychosocial predictors of dementia caregiver desire to institutionalize: caregiver, care recipient, and family relationship factors. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19:16–20. doi: 10.1177/0891988705284713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright LK. Alzheimer’s disease afflicted spouses who remain at home: can human dialectics explain the findings? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitlatch CJ, Schur D, Noelker LS, et al. The stress process of family caregiving in institutional settings. Gerontologist. 2001;41:462–473. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton MC, Piercy KW, Rabins PV, et al. Caregiver-recipient closeness and symptom progression in Alzheimer disease. The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:560–568. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgener S, Twigg P. Relationships among caregiver factors and quality of life in care recipients with irreversible dementia. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2002;16:88–102. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman S, Lazarus R. Stress, Appraisal, and Coing. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folkman S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2008;21:3–14. doi: 10.1080/10615800701740457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinke CL. What Does it Mean to Cope. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, et al. Coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: the LASER-AD study. J Affect Disord. 2006;90:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mausbach BT, Aschbacher K, Patterson TL, et al. Avoidant coping partially mediates the relationship between patient problem behaviors and depressive symptoms in spousal Alzheimer caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:299–306. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192492.88920.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kneebone, Martin PR. Coping and caregivers of people with dementia. Br J Health Psychol. 2003;8:1–17. doi: 10.1348/135910703762879174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li R, Cooper C, Bradley J, et al. Coping strategies and psychological morbidity in family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, et al. Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:929–936. doi: 10.1002/gps.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClendon MJ, Smyth KA, Neundorfer MM. Survival of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: caregiver coping matters. Gerontologist. 2004;44:508–519. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodaty H, McGilchrist C, Harris L, et al. Time until institutionalization and death in patients with dementia. Role of caregiver training and risk factors. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:643–650. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060073021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breitner JC, Wyse BW, Anthony JC, et al. APOE-epsilon4 count predicts age when prevalence of AD increases, then declines: the Cache County Study. Neurology. 1999;53:321–331. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Plassman BL, et al. An adaptation of the modified mini-mental state examination: analysis of demographic influences and normative data: the cache county study. Neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, and behavioral neurology. 2002;15:28–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. American Psychiatric Association; 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British journal of psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Carr JE, et al. The Ways of Coping Checklist: Revision and Psychometric Properties. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1985;20:3–26. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabins PV, Mace NL, Lucas MJ. The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA. 1982;248:333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabins PV, Fitting MD, Eastham J, et al. Emotional adaptation over time in care-givers for chronically ill elderly people. Age Ageing. 1990;19:185–190. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, et al. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52:P159–166. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.4.p159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Treiber KA, Carlson MC, Corcoran C, et al. Cognitive stimulation and cognitive and functional decline in Alzheimer’s disease: the cache county dementia progression study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 66:416–425. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]