Abstract

Age-related declines in neuromuscular function are well-documented, though the mechanisms underlying these deficits are unclear. Specific changes in corticospinal and intracortical neurophysiology may contribute, but have not been well studied, especially in lower extremity muscles. Furthermore, variations in physical activity levels may potentially confound the interpretation of neurophysiologic findings. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to quantify differences in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) measures of corticospinal and intracortical excitability of the quadriceps between healthy, active older and younger adults. Twenty younger (age: 25 ± 2.4 years; body mass index [BMI]: 22.1 ± 2.96 kg/m2; 11 males and 9 females) and twenty older (age: 68 ± 5.5 years; BMI: 26.8 ± 3.78 kg/m2; 11 males and 9 females) subjects who exercised regularly (at least 30 minutes, 3 times/week) completed testing. Motor evoked potentials (MEPs) were measured by superficial electromyographic recordings of the vastus lateralis (VL). Measures of corticospinal excitability using a double cone TMS coil included resting motor thresholds (RMT), resting recruitment curves (RRC) and silent periods (SP). Intracortical excitability was measured using paired pulse paradigms for short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF). No statistically significant differences between older and younger adults were found for RMT, RRC slopes, SP, SICI or ICF measures (p>0.05). The physically active nature of the older adults included in this study may have contributed to the lack of differences in corticospinal and intracortical excitability since physical activity in older adults attenuates age-related declines in neuromuscular function.

Keywords: transcranial magnetic stimulation, muscle, aging, electromyography, motor evoked potential

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with a number of physiological and neuromuscular changes that have been well described (Booth et al., 1994; Brooks and Faulkner, 1994). In particular, aging is related to impaired neuromuscular function as demonstrated by reduced muscle strength and motor performance (Booth et al., 1994; Brooks and Faulkner, 1994). Multifaceted age-related changes in the physiology of the human brain likely contribute to some of these motor deficits in older adults (Anderson and Rutledge, 1996; Mattson et al., 2004; McGinley et al., 2010). For example, studies have found age-related alterations in neuronal architecture and dendritic density (Anderson and Rutledge, 1996) as well as changes in neurotransmitter levels (Mattson et al., 2004). In addition, a number of studies have found age-related changes in the responsiveness of spinal motoneurons (Chalmers and Knutzen, 2004; Kido et al., 2004; Laidlaw et al., 2000; Semmler et al., 2000), including decreased spinal excitability (Kido et al., 2004) and increased variability in motor unit discharge rate (Laidlaw et al., 2000). Whether specific changes in corticospinal and intracortical neurophysiology also contribute to the decline in motor function with increasing age is still not clear.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the human motor cortex provides information regarding the responsiveness of both corticospinal and intracortical pathways to an imposed stimulus (Rossini et al., 2010). This technique has been increasingly used to elucidate information about physiological changes that might account for altered neuromuscular function. TMS uniquely contributes to our understanding of human neurophysiology through its ability to transiently interrupt, stimulate or modulate cortical areas of interest (Kluger and Triggs, 2007). Single pulse TMS can be used to assess corticospinal excitability by examining the motor threshold necessary to produce motor evoked potentials (MEPs), the rate of increase in MEPs with increasing levels of stimulation (recruitment curve), and silent periods (SPs). These responses are mediated at both cortical and spinal levels, providing overall information regarding corticospinal function. Cortical excitability can be more specifically assessed using paired-pulse TMS paradigms, which utilize a conditioning stimulus and a test stimulus at different interstimulus intervals (ISI) including short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF) (Ziemann, 2003; Ziemann et al., 1995).

A limited number of TMS studies have characterized motor corticospinal and, more specifically, intracortical changes associated with normal aging (Kossev et al., 2002; McGinley et al., 2010; Oliviero et al., 2006; Peinemann et al., 2001; Pitcher et al., 2003; Sale and Semmler, 2005; Smith et al., 2009; Wassermann, 2002). Findings from these studies have been mixed, with some suggesting decreased corticospinal or intracortical excitability with increasing age (Kossev et al., 2002; McGinley et al., 2010; Oliviero et al., 2006; Sale and Semmler, 2005) and others suggesting no age-related changes (Peinemann et al., 2001; Pitcher et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2009). Possibly, variability in subject physical activity levels might help explain some of the mixed findings, since physical activity has been shown to enhance motor cortex plasticity (Cirillo et al., 2009) and attenuate neuromuscular deficits in older adults (Candow et al., 2011; Clark and Fielding, 2011). Therefore, evaluating younger and older individuals with comparable physical activity levels would allow for a more accurate assessment of specific age-related changes in corticospinal or intracortical excitability. Furthermore, most TMS investigations have focused on upper extremity muscles. Yet, evaluation of differences in corticospinal and intracortical excitability of lower extremity muscles using TMS measures is clinically important because lower extremity muscle weakness, particularly in the quadriceps, has profound functional consequences, especially in older individuals. Quadriceps weakness has been associated with decreased gait speed (Brown et al., 1995), balance (Moxley Scarborough et al., 1999), stair-climbing (Mizner et al., 2005) and chair rising ability (Skelton et al., 1994), as well as an increased risk for falls (Moreland et al., 2004). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to quantify differences in TMS measures of corticospinal and intracortical excitability of the quadriceps between healthy, active younger and healthy, active older adults. We hypothesized that corticospinal excitability would be reduced in older adults as measured by resting motor threshold (RMT), resting recruitment curves (RRCs) and SP duration. Further, we believed that intracortical excitability would be similarly reduced as measured by SICI and ICF paradigms.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Younger subjects were recruited between the ages of 20–35. Older subjects were recruited between 60–80 years old. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, peripheral neuropathy, neurological or psychiatric disease, lower extremity orthopaedic injury, knee surgery or current knee pain, or were taking medications known to alter cortical excitability. Additionally, all subjects were screened to meet the TMS safety criteria as outlined by the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Wassermann, 1998). All subjects reported exercising at least 30 minutes per day, three days per week. We chose to target physically active older adults to compare to physically active younger adults, because this approach would better isolate age-related changes in corticospinal and intracortical excitability without the potential confounder of decreased physical activity that often accompanies increasing age. The study was approved by the university institutional review board. All subjects provided written, informed consent before participation.

2.2. Electromyography Recording

Subjects were tested in a seated and reclined position with approximately 45° of hip flexion. Surface EMG of the vastus lateralis (VL) muscle was collected using two, 3 cm Ag-Ag/Cl electrodes (ConMed, Utica, NY, USA) placed midway between the iliac crest and the lateral joint line of the knee. The leg with the lowest background EMG noise was utilized (left leg: n=12 younger; n=15 older). Ground electrodes were placed on the contralateral medial malleolus of the ankle. EMG was collected using a Biopac MP100 unit and AcqKnowledge (v3.8.1) software (Biopac System Inc., Goleta, CA). The EMG signal was amplified at a gain of 2,000 and was filtered online with a high pass of 10 Hz and low pass of 500 Hz.

2.3. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Motor evoked potentials were recorded by stimulating the motor cortex contralateral to the VL being tested with a double cone coil connected to two Magstim 2002 units joined by a BiStim2 module (The Magstim Company, Whitland, UK). Using a posterior-anterior orientation of the double cone coil, the optimal stimulating point was found by locating the area that produced the largest and most consistent MEPs after providing stimuli to a variety of positions on a grid drawn on a lycra cap. All subsequent testing was performed over the optimal stimulating point. Stimuli were separated by at least three seconds.

The cut-off for MEP detection was calculated by first determining the peak-to-peak amplitude of the resting EMG signal. The threshold was set two standard deviations above this amplitude. The RMT was defined as the minimum stimulator intensity required to produce 4 of 8 MEPs whose peak-to-peak amplitudes exceeded this MEP threshold. Similarly, active motor threshold (AMT) was defined as the minimum stimulator intensity required to produce 4 of 8 MEPs whose peak-to-peak amplitudes were greater than the peak-to-peak amplitude plus two times the standard deviation of the EMG signal collected while the subject lifted his/her foot five centimeters off of the testing chair by extending the knee (Clark et al., 2008; Damron et al., 2008; McGinley et al., 2010). The average quadriceps EMG activity for all subjects while lifting their foot as a percentage of maximal EMG activity was 20.7±2.7% (mean ± SEM). Three trials of this contraction were collected to ensure consistent contraction levels across trials.

The RRC data were collected by providing eight stimuli at 6 stimulator intensities set at 80%, 90%, 100%, 110%, 120% and 130% of RMT. Next, paired pulse measurements were used to quantify intracortical excitability using a sub-threshold conditioning stimulus (80% RMT) followed by a supra-threshold test stimulus (120% RMT) separated by either 3 ms or 15 ms ISI (Chen et al., 1998; Kujirai et al., 1993). Pulses separated by 3 ms produce an inhibitory effect on the test stimulus (SICI) and pulses separated by 15 ms produce a facilitatory effect on the test stimulus (ICF) (Chen et al., 1998; Kujirai et al., 1993). Paired pulse parameters were chosen according to well-established guidelines (Manganotti et al., 2008; Zanette et al., 2004). Eight SICI followed by eight ICF stimuli were administered. One set of 8 stimuli at 120% RMT followed paired pulse testing and was used to normalize data from paired pulse testing. Finally, SP was measured from EMG recordings with eight sets of TMS stimuli delivered at 120% of AMT while the subject extended his/her knee as described earlier. The SP duration was measured from MEP onset to resumption of normal EMG activity, defined as the instant when the amplitude of the post-stimulus EMG activity changed by at least the value of the mean EMG activity from knee extension ± 1 SD (Garvey et al., 2001).

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

The RRC curves were formed by first log10 transforming the raw, peak-to-peak MEP values recorded during RRC testing. This transformation was completed to correct for nonlinearity of curves for slope comparison and statistical analysis (Roberts et al., 2007). Next, the transformed MEPs were averaged at each stimulation intensity for each subject and plotted on a stimulus response curve. Slopes for each individual’s RRC were acquired using linear regression analysis between 100% RMT to 130% RMT. Finally, mean group slopes were calculated using individual subject RRC slopes. Paired pulse values are reported as the ratio of the mean paired pulse MEP peak-to-peak amplitude to the mean control stimulus (120% RMT) MEP amplitude. Data for each TMS paradigm were averaged within each individual and then across individuals to calculate group means, which were used for statistical analysis.

All outcome measures between older and younger subjects were compared using independent samples student t-tests. Data from some subjects were considered to be outliers, which was defined as data falling greater than three standard deviations from the group mean (Hoeger Bement et al., 2009). Outliers were excluded from statistical analysis. Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated. All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

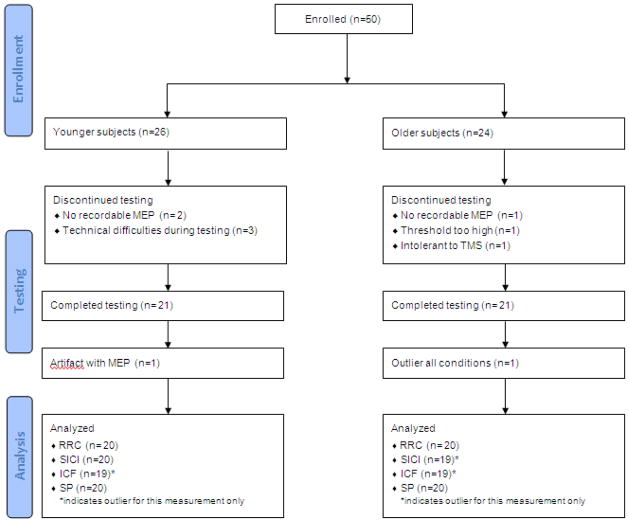

Twenty-six healthy, younger and 24 healthy, older subjects met the inclusion criteria. Twenty-one younger (age: 25 ± 2.4 years; body mass index [BMI]: 22.1 ± 2.96 kg/m2; 11 males and 9 females) and twenty-one older (age: 68 ± 5.5 years; BMI: 26.8 ± 3.78 kg/m2; 11 males and 9 females) subjects completed testing (mean ± standard deviation). Twenty subjects from each group were included in data analyses. One younger subject was determined to be a statistical outlier (> 3 standard deviations from mean), while one older subject was excluded because an EMG artifact prevented data analysis. Subject exclusion from testing or data analysis is detailed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for subject inclusion and exclusion for study participation and data exclusion in each testing paradigm

RRC= resting recruitment curve; SICI= short interval intracortical inhibition; ICF= intracortical facilitation; SP= silent period

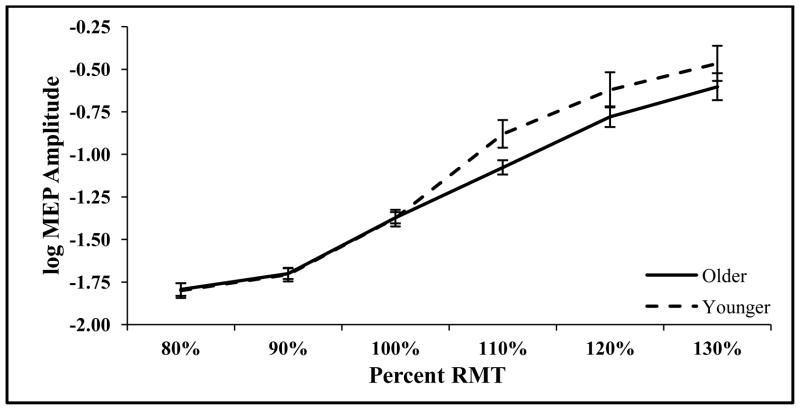

No differences in mean knee extension EMG as a percentage of maximal EMG activity were observed between groups (P=0.67), indicating comparable levels of muscle recruitment. There were no significant differences in corticospinal excitability (Table 1) between older and younger adults as measured by RMT (P=0.47) and 100% RMT MEP amplitude (P=0.49) (Table 1). In addition, the slope of the RRC was not different in older compared to younger adults (P=0.22), but the curve tended to be shifted to the right for older adults, suggesting decreased corticospinal excitability (Fig. 2). Similarly, SP duration suggested a pattern of less corticospinal excitability for older adults, although there were not significant differences between older and younger adults (P=0.13).

Table 1.

Cortispinal and intracortical exicitabilty outcomes for younger and older adults (Mean±SEM)

| Paradigm | Younger | Older | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Active EMGa | 21.80 ± 2.68% | 19.50 ± 2.16% | 0.67 |

| MEP Amplitude μVb | 63.70 ± 10.10 | 55.90 ± 4.84 | 0.49 |

| RMT | 59.10 ± 1.76% | 61.20 ± 2.27% | 0.47 |

| RRC Slope μV/% RMT | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.22 |

| SICI | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 0.93 |

| ICF | 3.00 ± 0.34 | 3.21 ± 0.32 | 0.66 |

| Silent Period (ms) | 95.20 ± 7.93 | 112.00 ± 8.92 | 0.13 |

EMG= electromyography; MEP= motor evoked potential; RMT= resting motor threshold; RRC= resting recruitment curve; SICI= short interval intracortical inhibition; ICF= intracortical facilitation

Knee extension EMG as % MVIC EMG.

MEP amplitude=raw peak-to-peak EMG of 100% RMT MEP

Fig. 2.

Resting recruitment curves with log10 transformation to correct for nonlinearity of curves to compare slopes between younger (n=20) and older adults (n=20) (mean ± SEM).

MEP= motor evoked potential; RMT= resting motor threshold.

The SICI and ICF techniques used to assess intracortical excitability successfully produced inhibition and facilitation, as expected. There were no significant differences in intracortical excitability for SICI (P=0.93) or ICF (P=0.66) between healthy older and younger adults.

4. Discussion

Age-related declines in neuromuscular function are well-documented (Frontera et al., 1991), though our understanding of the mechanisms underlying these deficits is incomplete. This study examined differences in corticospinal and intracortical excitability of the quadriceps between older and younger adults. As such, this is the first study to investigate age-related changes in corticospinal and intracortical excitability of the quadriceps, one of the most important lower extremity muscles for physical function(Brown et al., 1995; Moreland et al., 2004; Moxley Scarborough et al., 1999; Skelton et al., 1994). Furthermore, an important feature of this investigation was the inclusion of younger and older adults with comparable physical activity levels to specifically evaluate age-related changes in corticospinal or intracortical excitability without the additional confounder of decreased physical activity that often accompanies increasing age.

Contrary to our hypothesis, corticospinal excitability, as measured by the slope of the RRC, did not significantly differ between active older and younger adults. A lack of age-related differences in the slope of the RRC has been reported previously for the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Pitcher et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2009). However, Pitcher and colleagues (2003) noted a shift in the RRC in older adults, indicating that older adults required a greater stimulator output to achieve equivalent amplitude MEPs than did younger adults and that this difference was more evident in females compared to males. This suggests that age-related differences in corticospinal excitability as measured by the RRC may be sex dependent. Although the present study was not powered to detect sex differences, it is possible that sex differences could have impacted our results, specifically our RRC outcomes.

Similar to the RRC slope, there was no difference in SP duration between groups, suggesting that corticospinal excitability may not differ between healthy, active older and younger adults. Silent period duration is thought to be mediated by GABAB receptors and results from inhibition via both spinal and cortical mechanisms. Our SP results are in agreement with a recent study demonstrating no difference in SP duration in the extensor carpi radialis between older and younger adults (Fujiyama et al., 2009) and in disagreement with a study reporting that older adults had a shorter SP in the first dorsal interosseous muscle than younger adults (Oliviero et al., 2006). Though there is some discrepancy between our results and those of other authors, it should be noted that the SP duration demonstrated by our subjects is comparable to that reported previously within the quadriceps of healthy individuals (Heroux and Tremblay, 2006; Tremblay et al., 2001).

Contrary to our hypothesis, neither SICI nor ICF differed between groups. Previous research comparing intracortical excitability in upper extremity musculature between older and younger adults is conflicting. Older adults have demonstrated increased (McGinley et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2009), decreased (Peinemann et al., 2001), and similar magnitudes of SICI (Oliviero et al., 2006) compared to younger individuals. In regards to ICF, McGinley et al. (2010) reported a reduction in ICF whereas Peinemann et al.(2001) noted no difference in ICF between older and younger adults. SICI is believed to be mediated by gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors(Ziemann, 2003), while ICF is thought to be mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Ziemann, 2003, 2004; Ziemann et al., 1995). Given the conflicting results, it seems that variable responses to GABAA and NMDA may present in different muscles with increasing age. Why this occurs is unclear and future research clarifying age-related changes in intracortical excitability in both the upper and lower extremity musculature appears necessary. Differences in stimulation parameters may also help explain the lack of agreement in findings. Previous researchers have utilized a conditioning stimulus equivalent to 75%(Peinemann et al., 2001) to 95% of RMT(McGinley et al., 2010) or AMT(Oliviero et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2009) with test stimuli sufficient to elicit an MEP of one(McGinley et al., 2010; Oliviero et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2009) to 1.5 μV.(Peinemann et al., 2001) Given the paucity of data from lower extremity muscles, it is unknown how different stimulation parameters influence the magnitude of intracortical excitability.

When considering the results of all TMS measures assessed in the present study, a pattern emerged to suggest that declines in neuromuscular function between active older and younger adults may be more spinally than cortically mediated. All of the TMS measures utilized in the present study assess cortical excitability. However, the RRC slope and SP duration also indicate spinal excitability. Interestingly, these two measurements trended in the direction of older adults being less excitable than younger adults (shallower RRC slope and longer SP duration in older adults) which may suggest greater influence from spinal than cortical factors. Incorporating measurements that primarily assess spinal excitability (e.g., Hoffmann reflex)(Knikou, 2008) may aid in elucidating the cortical versus spinal mechanisms underlying age-related declines in motor function.

Others have shown a differential decline in muscle strength with increasing age that more greatly affects the lower extremity compared to the upper extremity musculature (Chodzko-Zajko et al., 2009). Given this, and that some prior investigations demonstrate reductions in corticospinal and intracortical excitability within the upper extremity (McGinley et al., 2010; Oliviero et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2009), it seems counter-intuitive that the present study did not note such age-related changes. It is possible that the physically active nature of the older adults included in this study may have contributed to this finding. The older adult group was comprised of individuals who exercise for at least 30 minutes per day, three times per week. Older adults who participate in an exercise regimen may have improved motor function compared to similarly aged, sedentary adults (Candow et al., 2011; Clark and Fielding, 2011). As motor function is partially mediated by corticospinal and intracortical mechanisms, a lesser decline in motor function with regular exercise might translate to a smaller decline in corticospinal and intracortical excitability. A recent study by McGregor and colleagues (2011) supports this idea. These authors noted that the cortical SP duration differed between physically active and sedentary older adults (McGregor et al., 2011), suggesting that physical activity may slow age-related declines in neuromuscular function. As motor function was not specifically assessed in the present study, we cannot be certain that motor function in our subjects was superior to that in sedentary, older adults or equivalent to our younger, active group. Therefore, future investigations into age-related changes in neuromuscular function may benefit from stratifying older adults based on physical activity levels and comparing both sedentary and active older adults to younger adults.

Despite previous studies noting age-related differences in corticospinal and intracortical excitability, some studies have not found age-related differences using TMS measures of excitability. In a series of studies examining MEP amplitude and intracortical excitability, Wassermann (2002) determined that the magnitudes of SICI and ICF were not associated with subject age. This study (Wassermann, 2002) examined very few older adults, though, suggesting these results may not be representative of the older population as a whole. However, similar results were obtained by Smith et al.(2009), who noted that SICI and ICF were not associated with age when measured in resting muscle. As such, it may not be surprising that our study failed to detect differences in TMS measures, particularly intracortical excitability in resting muscles, between older and younger adults.

Though commonly utilized, TMS is not without limitations. Intra- and inter-individual variability is high, with reports upwards of 50% depending on the measurement technique (Wassermann, 2002). Factors such as caffeine and alcohol intake, circadian rhythm, circulating hormone levels, and other factors that influence neural function have been suggested to contribute to the variability in TMS measures (Wassermann, 2002). Even with attempts to control for factors that influence corticospinal and intracortical excitability, such a large variability may confound the ability to detect differences between groups. An additional limitation of the present study is that we did not assess lower extremity motor function. Such an assessment may have helped evaluate how comparable the older adults studied were to the younger adults in terms of physical function. Future studies would benefit from incorporating motor function assessment to complement TMS outcomes.

5. Conclusion

Corticospinal and intracortical excitability were similar between healthy, active older and younger adults. Age-related declines in neuromuscular function are likely multifactorial in nature, consisting of central and peripheral mechanisms. Exercise may ameliorate these declines at multiple levels and future studies should examine the interaction between physical activity, age and neuromuscular function. Given the importance of quadriceps strength in functional performance and reducing fall risk in older adults, future studies that further elucidate the underlying causes of age-related neuromuscular deficits are imperative so that strategies to counter these declines can be implemented.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katrina Maluf PhD, Jennifer Stephenson PhD, and Jennifer Hide DPT for their contributions to this investigation. Corticospinal and Intracortical Excitability of Quadriceps

Role of the funding source

Support for this study was provided by Grant Number K23-AG029978 from National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health. Sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: no authors have a conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson B, Rutledge V. Age and hemisphere effects on dendritic structure. Brain. 1996;119 (Pt 6):1983–1990. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.6.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth FW, Weeden SH, Tseng BS. Effect of aging on human skeletal muscle and motor function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:556–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Skeletal muscle weakness in old age: underlying mechanisms. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:432–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown M, Sinacore DR, Host HH. The relationship of strength to function in the older adult. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(Spec No):55–59. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Abeysekara S, Zello GA. Short-term heavy resistance training eliminates age-related deficits in muscle mass and strength in healthy older males. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:326–333. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bf43c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalmers GR, Knutzen KM. Recurrent inhibition in the soleus motor pool of elderly and young adults. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;44:413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen R, Tam A, Butefisch C, Corwell B, Ziemann U, Rothwell JC, Cohen LG. Intracortical inhibition and facilitation in different representations of the human motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2870–2881. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, Skinner JS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1510–1530. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cirillo J, Lavender AP, Ridding MC, Semmler JG. Motor cortex plasticity induced by paired associative stimulation is enhanced in physically active individuals. J Physiol. 2009;587:5831–5842. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark BC, Issac LC, Lane JL, Damron LA, Hoffman RL. Neuromuscular plasticity during and following 3 wk of human forearm cast immobilization. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:868–878. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90530.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark DJ, Fielding RA. Neuromuscular Contributions to Age-Related Weakness. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damron LA, Dearth DJ, Hoffman RL, Clark BC. Quantification of the corticospinal silent period evoked via transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;173:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Lutz KJ, Evans WJ. A cross-sectional study of muscle strength and mass in 45- to 78-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:644–650. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.2.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujiyama H, Garry MI, Levin O, Swinnen SP, Summers JJ. Age-related differences in inhibitory processes during interlimb coordination. Brain Res. 2009;1262:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garvey MA, Ziemann U, Becker DA, Barker CA, Bartko JJ. New graphical method to measure silent periods evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1451–1460. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00581-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heroux ME, Tremblay F. Corticomotor excitability associated with unilateral knee dysfunction secondary to anterior cruciate ligament injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:823–833. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeger Bement MK, Weyer A, Hartley S, Yoon T, Hunter SK. Fatiguing exercise attenuates pain-induced corticomotor excitability. Neurosci Lett. 2009;452:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kido A, Tanaka N, Stein RB. Spinal excitation and inhibition decrease as humans age. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;82:238–248. doi: 10.1139/y04-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kluger BM, Triggs WJ. Use of transcranial magnetic stimulation to influence behavior. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:491–497. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knikou M. The H-reflex as a probe: pathways and pitfalls. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;171:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kossev AR, Schrader C, Dauper J, Dengler R, Rollnik JD. Increased intracortical inhibition in middle-aged humans; a study using paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurosci Lett. 2002;333:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00986-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Ferbert A, Wroe S, Asselman P, Marsden CD. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1993;471:501–519. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laidlaw DH, Bilodeau M, Enoka RM. Steadiness is reduced and motor unit discharge is more variable in old adults. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:600–612. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200004)23:4<600::aid-mus20>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manganotti P, Acler M, Zanette GP, Smania N, Fiaschi A. Motor cortical disinhibition during early and late recovery after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:396–403. doi: 10.1177/1545968307313505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattson MP, Maudsley S, Martin B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGinley M, Hoffman RL, Russ DW, Thomas JS, Clark BC. Older adults exhibit more intracortical inhibition and less intracortical facilitation than young adults. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGregor KM, Zlatar Z, Kleim E, Sudhyadhom A, Bauer A, Phan S, Seeds L, Ford A, Manini TM, White KD, Kleim J, Crosson B. Physical activity and neural correlates of aging: A combined TMS/fMRI study. Behav Brain Res. 2011;222:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizner RL, Petterson SC, Snyder-Mackler L. Quadriceps strength and the time course of functional recovery after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:424–436. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.7.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreland JD, Richardson JA, Goldsmith CH, Clase CM. Muscle weakness and falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1121–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moxley Scarborough D, Krebs DE, Harris BA. Quadriceps muscle strength and dynamic stability in elderly persons. Gait Posture. 1999;10:10–20. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(99)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliviero A, Profice P, Tonali PA, Pilato F, Saturno E, Dileone M, Ranieri F, Di Lazzaro V. Effects of aging on motor cortex excitability. Neurosci Res. 2006;55:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peinemann A, Lehner C, Conrad B, Siebner HR. Age-related decrease in paired-pulse intracortical inhibition in the human primary motor cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2001;313:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitcher JB, Ogston KM, Miles TS. Age and sex differences in human motor cortex input-output characteristics. J Physiol. 2003;546:605–613. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts DR, Ricci R, Funke FW, Ramsey P, Kelley W, Carroll JS, Ramsey D, Borckardt JJ, Johnson K, George MS. Lower limb immobilization is associated with increased corticospinal excitability. Exp Brain Res. 2007;181:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0920-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossini PM, Rossini L, Ferreri F. Brain-behavior relations: transcranial magnetic stimulation: a review. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2010;29:84–95. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2009.935474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sale MV, Semmler JG. Age-related differences in corticospinal control during functional isometric contractions in left and right hands. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1483–1493. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00371.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semmler JG, Steege JW, Kornatz KW, Enoka RM. Motor-unit synchronization is not responsible for larger motor-unit forces in old adults. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:358–366. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skelton DA, Greig CA, Davies JM, Young A. Strength, power and related functional ability of healthy people aged 65–89 years. Age Ageing. 1994;23:371–377. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith AE, Ridding MC, Higgins RD, Wittert GA, Pitcher JB. Age-related changes in short-latency motor cortex inhibition. Exp Brain Res. 2009;198:489–500. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1945-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tremblay F, Tremblay LE, Colcer DE. Modulation of corticospinal excitability during imagined knee movements. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:230–234. doi: 10.1080/165019701750419635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wassermann EM. Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, June 5–7, 1996. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;108:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(97)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wassermann EM. Variation in the response to transcranial magnetic brain stimulation in the general population. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zanette G, Manganotti P, Fiaschi A, Tamburin S. Modulation of motor cortex excitability after upper limb immobilization. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1264–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziemann U. Pharmacology of TMS. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;56:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ziemann U. TMS and drugs. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1717–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ziemann U, Lonnecker S, Paulus W. Inhibition of human motor cortex by ethanol. A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Brain. 1995;118 (Pt 6):1437–1446. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.6.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]