Abstract

Objective

To compare the characteristic meal patterns of adolescents with and without loss of control (LOC) eating episodes.

Method

The Eating Disorder Examination was administered to assess self-reported LOC and frequency of meals consumed in an aggregated sample of 574 youths (12-17 y; 66.6% female; 51.2% Caucasian; BMI-z: 1.38 ± 1.11), among whom 227 (39.6%) reported LOC eating.

Results

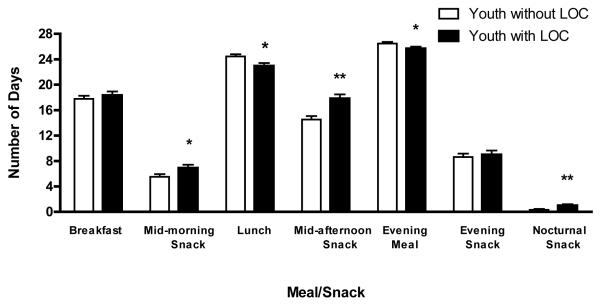

Compared to those without LOC, youth with LOC were less likely to consume lunch and evening meals (ps<.05), but more likely to consume morning, afternoon, and nocturnal snacks (ps≤.05), accounting for age, sex, race, socio-economic status, BMI-z, and treatment-seeking status.

Discussion

Adolescents with reported LOC eating appear to engage in different meal patterns compared to youth without LOC, and adults with binge eating. Further research is needed to determine if the meal patterns that characterize adolescents with LOC play a role in worsening disordered eating and/or excessive weight gain.

Keywords: Loss of control eating, adolescents, meal patterns

Research suggests that adults who engage in binge eating behaviors tend to report consuming meals and snacks with irregular frequency. In a community sample of women classified as having binge eating disorder (BED), bulimia nervosa, or no eating disorder, individuals with bulimia nervosa consumed fewer meals than both the control and BED groups.1 Notably, this study found that more frequent meal consumption and more frequent dinner consumption were correlated with fewer binge eating episodes among women with BED.1 This finding was replicated in a sample of obese treatment-seeking individuals with BED such that men and women who routinely ate three meals a day reported fewer binge eating episodes than those with irregular meal patterns.2 With regard to snack intake, there are data showing that adults’ consumption of evening snacks is associated with more frequent binge eating episodes.2, 3 Despite these studies in adults, there are no data examining the eating patterns among youth with binge or loss of control (LOC) eating episodes.

LOC eating refers to an eating episode during which a subjective experience of being unable to control what or how much is being eaten occurs, regardless of the reported amount of food consumed.4 Although full-syndrome BED is uncommon among youth, infrequent LOC episodes (~1 time per month) are commonly reported and appear to be an indicator of emotional distress.4 LOC eating is associated with adiposity5 and predictive of excess weight gain over time.6 LOC eating also is predictive of the development of partial or full-syndrome BED.7 Thus, elucidating the eating patterns of children who report such episodes may help to guide intervention efforts.

We therefore examined the relationship between LOC eating and meal and snack patterns in a convenience sample of adolescents. Based upon the literature in adults with binge eating, we hypothesized that LOC eating would be associated with the reported consumption of irregular meal patterns, such that youth with LOC would be less likely to consume all three meals each day. Furthermore, we hypothesized that youth with LOC eating would report more frequent consumption of afternoon or evening snacks compared to their peers without LOC eating.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from several studies on eating behavior and obesity conducted at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS). Youth between the ages of 12 and 17 years who completed the Eating Disorder Examination were included. Participants were either non-treatment seeking boys and girls serving as healthy volunteers in eating behavior studies (NCT00320177, NCT00631644, NCT00001195), prevention-seeking girls participating in an excess weight-gain prevention pilot study with a BMI between the 75th and 97th percentiles (NCT00263536), prevention-seeking girls with a BMI between the 75th and 97th percentiles who also reported at least one episode of LOC eating in the previous month (NCT00680979), or treatment-seeking boys and girls with a BMI at or above the 95th percentile and at least one obesity-related comorbidity such as hypertension or sleep apnea (NCT00001522). Adolescents from the latter three protocols were studied prior to initiation in any intervention. Youth were excluded for major medical (other than an obesity-related comorbidity for the treatment-seeking study) or psychiatric conditions other than BED, pregnancy, or taking medications known to affect appetite and/or weight. Youth who had lost more than 5% of their body weight in the 3 months prior to assessment or who were currently involved in weight loss treatment programs were also excluded.

Participants were recruited through the NIH clinical trials website, local area community flyer postings, posters at physician offices, and direct mailing to homes within a 50-mile radius of Bethesda, Maryland. All studies were approved by the NICHD institutional review board. NCT00680979 was also approved by the USUHS IRB. Written consent and assent were provided by parents and children, respectively.

Procedures

For the non-intervention and treatment studies, potential participants and a parent or guardian were seen at the NIH Hatfield Clinical Research Center. For the prevention study, interested families participated in two screening assessments at USUHS and the NIH on separate days.

Measures

Body Composition

Following an overnight fast, weight was measured using a calibrated scale, and height was measured in triplicate by stadiometer to obtain an average height. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was computed by dividing weight (kg) by the square of height (m). BMI-z scores were calculated using the Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts.8

Socioeconomic Status

The parent-reported Hollingshead index score9 was used to assess socioeconomic status.

Loss of Control Eating and Reported Meal and Snack Intake

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) version 12.0D10 was used to determine the presence or absence of LOC eating (objectively and subjectively large binge episodes) in the month prior to assessment. In pediatric samples, the EDE has demonstrated good interrater reliability and discriminant validity for eating episodes.5, 11, 12 The EDE also assessed meal frequency (breakfast, lunch, and evening meal) as well as snack frequency (mid-morning, afternoon, evening, and nocturnal) during the 28 days immediately prior to assessment. Evening snacks occur after an evening meal but prior to going to bed, whereas nocturnal snacks occur when an individual gets up during the night to eat before returning to bed. According to the EDE, the frequency of meals and snacks are coded according to the following scale: “0” indicates that the meal/snack was consumed on none of the past 28 days, “1” indicates between 1 and 5 days, “2” represents that the meal/snack was consumed between 6 and 12 days, “3” indicates between 13 and 15 days, “4” represents between 16 and 22 days, “5” indicates between 23 and 27 days, and “6” indicates that the meal or snack was consumed on all 28 days. Since these codes are ordinal, but are based on an underlying continuous variable (number of days), we followed common practice that involves transforming codes into numeric values that represent midpoints.13 As a result, the data presented are more representative of the actual number of days that meals and snacks were reported to be consumed. This approach is considered valid when intervals are small and the sample size is large,13 both of which are the case in the present study. Therefore, “1” was recoded as 3 days in the past month, “2” recoded as 9 days, “3” recoded as 14 days, “4” as 19 days, “5” as 25 days, and “6” recoded as 28. Pre-specified categorical variables were created to indicate the presence versus absence of daily consumption for each meal or snack (a rating of 6 on the EDE, indicating all of the past 28 days), or most day consumption (a rating of 5 or 6 on the EDE, representing ≥23 out of the past 28 days). Additionally, a pre-specified categorical variable was created to indicate whether all three meals were consumed on each of the past 28 days, in accordance with Masheb and Grilo’s definition of regular eating.2

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc, 2009, Chicago, IL). Data were screened for normality, with satisfactory skew and kurtosis for all variables of interest. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted to examine potential differences in eating patterns among youth with and without LOC eating. The independent variable was LOC eating status (presence or absence), and the dependent variables were meal or snack frequency. Binary logistic regressions were performed to ascertain whether LOC eating status was associated with a decreased probability of regularly consuming all three meals, as well as individual meal and snack time points. Covariates for all analyses included age (years), race (coded as non-Hispanic Caucasian or Other), sex (coded as male or female), socioeconomic status, BMI-z score, and intervention-seeking status (coded as intervention-seeking or healthy volunteer). Differences and associations were considered significant when p values were ≤ 0.05. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

Participants were 574 adolescents (66.6% female) between the ages of 12 and 17 y (mean ± SD, 14.96 ± 1.47). The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample was 51.2% non-Hispanic Caucasian, 37.8% African American, 4.0% Asian, 2.6% Latino or Hispanic, 2.3% Multiple Races, 0.4% American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 1.7% self-identified Other or Unknown. BMI ranged from 16.10 to 88.05 (29.75 ± 10.36) kg/m2, with corresponding BMI-z from -2.24 to 3.44 (M ± SD, 1.38 ± 1.11).

Meal and Snack Frequency

Breakfast was the least frequently consumed meal (17.82 ± 9.08 days), followed by lunch (23.77 ± 6.37 days), with an evening meal (dinner) consumed the most frequently (26.11 ± 4.22 days). Afternoon snacks were the most commonly consumed snack (16.02 ± 9.28 days), followed by evening snacks (8.92 ± 9.15 days), morning snacks (6.20 ± 7.47 days), and nocturnal snacks (0.61 ± 2.59 days). In examining regular meal consumption, 37.0% of the sample reported eating all three meals at least 23 of the past 28 days, but only 8.0% of youth reported consuming three meals every day in the past month. Therefore, we adopted a wider criterion to define regular eating as consuming all three meals on at least 23 of the past 28 days.

LOC Eating and Meal/Snack Frequency

Two-hundred twenty-seven (39.6%) youth reported at least one episode of LOC in the month prior to assessment (1.03 ± 1.59 episodes, range = 1-5). Table 1 displays participant characteristics based on the presence or absence of reported LOC. Adjusting for all covariates, youth with LOC eating reported consuming lunch (p= .016) and dinner (p= .043) significantly less frequently in the month prior to assessment than youth without LOC eating (Figure 1). Examined categorically and adjusted for the same covariates, youth with LOC eating had a 44% decreased likelihood of regularly consuming lunch (AOR= .56, 95% CI= .35 - .89, p= .01) and had a 53% decreased likelihood of regularly consuming dinner (AOR = .47, 95% CI= .23 - .96, p= .04) on most days in the previous month compared to youth without LOC. There were no differences between youth with and without LOC with regard to reported breakfast consumption frequency (p= .51; Figure 1) or regularity (p= .98).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics by LOC

| LOC (n=227) |

No LOC (n= 347) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.86 ± 1.56 | 15.03 ± 1.41 | .20 |

| Sex (% female) | 82.38 | 56.20 | <.001 |

| Race (% white) | 51.10 | 51.59 | .91 |

| Socioeconomic Status (Median) |

2.00 | 2.00 | .72 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.08 ± 9.64 | 29.54 ± 10.81 | .54 |

| BMI-z | 1.57 ± 0.83 | 1.27 ± 1.25 | .001 |

LOC: Loss of control; BMI: Body Mass Index; BMI-z: Body Mass Index z-score

Figure 1.

Reported meal and snack consumption on the EDE in past 28 days among youth with and without LOC eating. Means, standard errors adjusted for covariates: age, race, sex, socioeconomic status, BMI-z score, and intervention-seeking status. EDE = Eating Disorder Examination; LOC = Loss of control. *p< .05, **p< .01.

There also were a number of differences in snacking. After adjusting for all covariates, youth with LOC eating reported consuming mid-morning (p= .05) and afternoon snacks (p< .01) more often than youth without LOC eating (Figure 1). Although adolescents rarely endorsed nocturnal snacking, youth with LOC reported consuming more nocturnal snacks than youth without LOC eating (p< .01; Figure 1). No differences were found with regard to evening snacking (p= .68; Figure 1). When snacking was considered categorically, youth with LOC eating had a 65% increased likelihood of regularly consuming afternoon snacks than youth without LOC (AOR= 1.65, 95% CI= 1.10 – 2.48, p= .02), but no significant differences were observed among other snack time points (ps= .26 - .99).

Youth with LOC eating did not differ from youth without LOC eating on reported consumption of all three meals (breakfast, lunch, and an evening meal) on at least 23 of the past 28 days in analyses adjusting for all relevant covariates (AOR= .75, 95% CI= .49 – 1.14, p= .18).

When analyzing only the intervention-seeking youth, all findings for snack intake remained the same. The prevalence with which lunch (p= .14) and dinner (p= .16) meals were consumed was no longer significantly lower in youth with LOC. All categorical analyses remained the same.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between reported meal and snack consumption frequency in a sample of adolescents with and without loss of control (LOC) eating patterns. Youth with LOC eating reported consuming lunch and dinner less frequently, but morning, afternoon, and nocturnal snacks more frequently, than their non-LOC counterparts. Controlling for age, race, socioeconomic, and BMI-z, youth with LOC were less likely to regularly consume all three meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) most of the time compared to their peers without LOC eating.

The adult literature is inconsistent in regards to the relationship between binge eating behaviors and the consumption of specific meals.1-3 In the present sample of adolescents, we found that youth with LOC eating reported consuming fewer lunches and dinners. Although this finding does not entirely parallel Masheb and Grilo’s1 finding in adults that binge episodes are negatively correlated with evening meals only, it may reflect differences between adult and child samples. The vast majority of youth with LOC in our sample only reported one episode of LOC in the past month. Similar to data suggesting that the presence of any LOC is salient in youth,4 our findings on eating patterns may represent developmental differences between children with LOC and adults with BED.

As hypothesized, youth with LOC eating reported consuming more afternoon snacks than those without LOC. However, we did not find a relationship between evening snacking and LOC eating episodes as reported in the adult literature.2, 3 This finding suggests that the afternoon, likely the after-school time frame, may be a particularly vulnerable time for snacking among youth with LOC. It is possible that the afternoon is a time when adolescents are alone, devoid of social interaction and with limited parental control over food consumption. Furthermore, if the afternoon snacking reported by youth with LOC involves overeating or psychological distress, helping youth to find alternative reinforcers during this time period of the day, other than food, could potentially serve as one form of intervention. Given this finding, the afternoon may be a crucial time point to monitor within the day in order to prevent or limit LOC eating episodes. Since successful cognitive behavioral therapeutic approaches used to treat adults with BED can involve implementing a structured three meals and two planned snacks per day regimen,14 a similar approach needs to be studied to determine its effects on LOC eating frequency and BED development among youth.

Notably, regardless of LOC status, very few children reported consuming completely regular meals, and breakfast was the least commonly eaten meal. This finding is concerning given the proposed role of breakfast in appetite control15, 16 and weight-related outcomes in children and adolescents.17-19 By contrast, youth did appear to consume lunch and dinner with greater frequency and regularity, with three-quarters eating lunch and over ninety percent eating dinner regularly. More studies are needed to determine what role, if any, specific meal consumption plays in the promotion or reduction in disinhibited eating behaviors among children and adolescents.

Strengths of this study include a relatively large, diverse sample comprised of adolescents of all weight strata. Additionally, structured interviews were administered by interviewers who had received extensive training on how to assess LOC eating and meal and snack pattern intake. However, the present study utilizes cross-sectional data, so causal conclusions about meal and snack frequency and LOC eating patterns cannot be determined. Additionally, although we controlled for intervention-seeking status, the sample was comprised of a convenience sample of youth who were willing to participate in research studies. Therefore, participants may differ from adolescents in the general population.

In conclusion, youth with LOC eating appear to report different meal intake patterns compared to youth without LOC episodes. Further research should focus on the role that meal and snack patterns may play in the development of adverse eating and weight outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Research support: Intramural Research Program, NIH, NICHD 1ZIAHD000641 with NIMHD and OBSSR supplemental funding (to JAY); NIDDK 1R01DK080906 (to MTK); USUHS R0721C (to MTK); NICHD 1F32HD056762 and 1K99HD069516 (to LBS).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of USUHS, the U.S. Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Masheb RM, Grilo CM, White MA. An examination of eating patterns in community women with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:618–24. doi: 10.1002/eat.20853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Eating patterns and breakfast consumption in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1545–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey K, Rosselli F, Wilson GT, Debar LL, Striegel-Moore RH. Eating patterns in patients with spectrum binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:447–51. doi: 10.1002/eat.20839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanofsky-Kraff M. Binge Eating Among Children and Adolescents. In: Jelalian ES, R., editors. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Obesity. Springer; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:26–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.20580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:108–18. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. 12th edition Guilford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 317–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, et al. Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:95–105. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, Lask BD. The use of the eating disorder examination with children: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:391–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199605)19:4<391::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heitjan DF. Inference from grouped statistical data: A review. Statistical Science. 1989;4:184–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive behaviour therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: a comprehensive treatment manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. Guildford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira MA, Erickson E, McKee P, et al. Breakfast frequency and quality may affect glycemia and appetite in adults and children. J Nutr. 2011;141:163–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.114405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leidy HJ, Racki EM. The addition of a protein-rich breakfast and its effects on acute appetite control and food intake in ‘breakfast-skipping’ adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1125–33. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timlin MT, Pereira MA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Breakfast eating and weight change in a 5-year prospective analysis of adolescents: Project EAT (Eating Among Teens) Pediatrics. 2008;121:e638–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, Adams J, Metzl JD. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2005;105:743–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.007. quiz 61-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adol Health. 2006;39:842–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]