Abstract

FGF23 is a bone-derived hormone that regulates and is regulated by blood levels of phosphate and active vitamin D. Posttranslational glycosylation by the enzyme GALNT3 and subsequent processing by furin, has been demonstrated to be a regulated process that plays a role in regulating FGF23 levels. In physiologic states, FGF23 signaling is mediated by an FGF receptor and the co-receptor, Klotho. Recent work identifying a role for iron/hypoxia pathways in FGF23 physiology, and their implications are discussed. Beyond its importance in primary disorders of mineral metabolism, recent work implicates FGF23 in renal disease-associated morbidity, as well as possible roles in cardiovascular disease and skeletal fragility.

FGF23 physiology

Our knowledge of FGF23 physiology has advanced rapidly the past few years, yet many questions, paradoxes, and contradictions exist. One factor contributing to gaps in our understanding is the inability to control for reciprocal changes that occur when one arm of a complex multilevel feedback system is perturbed, during investigation of the hormone of interest. In addition, the shortcomings of animal and in vitro systems to model human physiology have at times introduced confusion. It is also becoming evident that FGF23 physiology in primary diseases of mineral metabolism (Table 1) is very different from that seen in renal disease. While this is particularly evident by the time patients reach stage 5 renal disease, divergence in the regulation of FGF23 secretion and action may begin even in the early stages of renal failure. This review focuses on recent advances on FGF23 function, with an emphasis on human physiology. Weight is given to clinical observations and studies and the related in vivo and in vitro studies that address and clarify underlying mechanisms. The emerging areas of FGF23 processing and the role of iron and iron-related pathways in both FGF23 synthesis and FGF23 processing will be discussed, as well as the alterations in FGF23 physiology that take place in renal insufficiency and failure.

Table 1.

Diseases associated with alterations in FGF23

| Gene | Location | Inheritance | OMIM # | Phenotype | REF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGF23-mediated hypophosphatemic disorders | ||||||

| XLH | PHEX | Xp22.11 | X-linked dominant | 307800 [MC1] | early onset rickets and osteomalacia; dental abscesses/carries and enthesopathies are common | [71, 91] |

| ADHR | FGF23 | 12p13.32 | Autosomal dominant | 193100 | rickets and osteomalacia; later onset possible especially in association with iron deficiency | [3, 78, 79] |

| ARHR1 | DMP1 | 4q22.1 | Autosomal recessive | 241520 | early onset rickets and osteomalacia, teeth with enlarged pulp chamber | [69, 70, 92] |

| ARHR2 | ENPP1 | 6q23.2 | Autosomal recessive | 613312 | early onset rickets and osteomalacia; dental carries, hypoplastic teeth; enthesopathies; cardiac valve anomalies | [72, 93-95] |

| HRHPT | KLOTHO* | 9q21.1/ 13q13.1 | Translocation t(9;13)(q21.1 3;q13.1) | 612089 | early onset hypophosphatemic rickets, hypercalcemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism of possible late-onset; late onset Arnold-Chiari I malformation | [53, 96] |

| TIO | N/A | N/A | Acquired | N/A | hypophosphatemia, osteomalacia, fractures, muscle weakness; uncommon in children; due to FGF23-secreting tumors | [25, 97] |

| MAS | GNAS | 20q13.32 | Sporadic | 174800 | hypophosphatemia, fractures, multiple extraskeletal manifestations common | [20, 98, 99] |

| OGD | FGFR1 | 8p11.23-p11.22 | Autosomal dominant | 166250 | Craniocynostosis, rhizomelia, non-ossifying bone lesions | [100] |

| FGF23-associated hyperphosphatemic disorders | ||||||

| HFTC/HHS | GALNT3 FGF23 KLOTHO | 2q24.3 12p13.32 13q13.1 | Autosomal recessive | 211900 | childhood onset (HHS) with painful diaphyseal thickening of the tibiae; hyperphosphatemia; predominantly periarticular soft tissue calcification, arterial calcification; dental pulp stones; KLOTHO mutation associated with primary hyperparathyroidism | [6, 15, 53, 101, 102] |

XLH: X-linked hypophosphatemia; PHEX: phosphate regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X chromosome; ADHR: autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets ; ARHR: autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets; DMP1: dentin matrix protein 1; ENPP1: ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1; HRHPT: hypophosphatemic rickets and hyperparathyroidism;

KLOTHO: the genetic mutation in HRHPT is a balanced translocation t(9;13)(q21.13;q13.1) with the translocation breakpoint mapped to position -49 of the 5-prime end of the KLOTHO gene, presumably causing increased levels of alpha-Klotho;

TIO: tumor-induced osteomalacia; MAS: McCune-Albright syndrome; OGD: osteoglophonic dysplasia; FGFR1: fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; HFTC: hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis; HHS: Hyperostosis hyperphosphatemic syndrome; GALNT3: UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3.

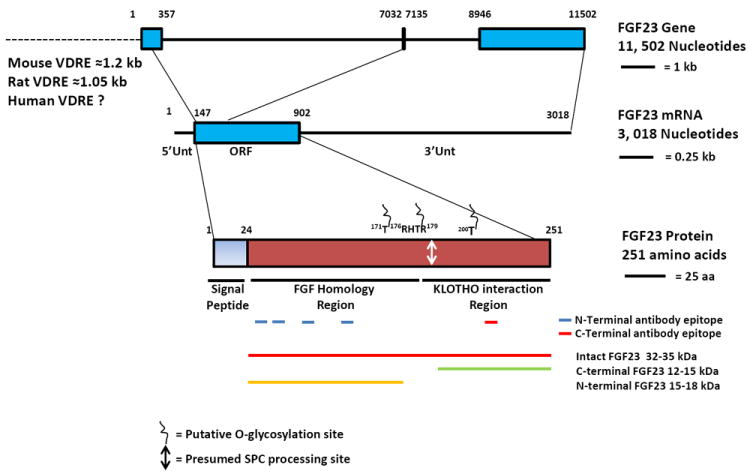

FGF23 Gene and Protein

The mouse and human FGF23 orthologs were discovered based on structural similarity to other FGFs [7]. The human FGF23 gene is located on chromosome 12p13, is 11,502 nucleotides long and contains 3 exons (Fig. 1). The intron-exon organization of the human and mouse orthologs is quite similar, and the FGF23 coding region is fairly conserved amongst species. The 5’-upstream promoter region of FGF23 gene is also highly conserved in the mouse, rat and human genes [8]. Putative binding sites within the ~2kb upstream region for transcription factors, such as GATA-binding factor (GATA), positive regulatory domain 1 binding factor (PRDF), RAR-related orphan receptor 1 (ROR), Ets 1 factor (ETSF), hepatic nuclear factor 4 (HNF-4), are conserved among these species [8]. While there is a consensus vitamin D receptor (VDR) binding element (VDRE) at approximately -1.0 to -1.2kB in the promoter of the mouse [8] and rat [9] genes, no analogous site exists in the promoter of the human gene, up to -5 kB.

Figure 1. Genomic organization, transcript profile and protein features of human FGF23.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences for the FGF23 gene (NC_000012), transcript (NM_020638) and protein (GenBank EAW88848) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databases. The three exons within the FGF23 gene are marked by boxes (blue). The 5’-upstream region for the FGF23 gene is also indicated (dashed line, not to scale). The area specific for the FGF23 coding region (open reading frame region; ORF) is also marked (blue box). 5’- and 3’-untranslated regions (5’Unt and 3’Unt) are indicated. Putative O-glycosylation sites and the subtilisin proprotein convertase (SPC) protease processing site are indicated. Different epitopes within the FGF23 protein that cross react to antibodies specific for the N-terminal region (marked by blue underlines) and C-terminal region (marked by red underline) are also indicated. The proteins that are commonly identified on Western blotting and their associated molecular weights are identified as indicated.

The human FGF23 protein is a 251 amino acid secretory hormone containing a 24 amino acid long signal peptide [7]; the rat and mouse FGF23 amino acid sequences are 72% and 71% homologous to human FGF23, respectively. The protein has two major functional domains, an N-terminal domain, which is the FGF homology region and a unique C-terminal region [4]. The N- and C-terminal domains are separated by a subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (SPC) proteolytic cleavage site (RXXR, 176RHTR179), a recognition cleavage site for proteins with endoprotease activity, such as furin. The SPC site that is conserved in FGF23 across all mammals is not seen in any other molecules in the FGF family. The importance of this site is highlighted by the fact that all of the original families identified with ADHR had mutations at this site [3]. The FGF receptor (FGFR) binding domain resides within the N-terminus, and the C-terminal domain contains the region of FGF23 that interacts with its co-receptor, alpha-Klotho (aKL) (Fig. 1) [10, 11], as opposed to beta-Klotho which is believed to interact with FGF-19 and FGF-21.

FGF23 is present in human circulation in several major forms; the hormonally active intact FGF23 (iFGF23), and inactive C-terminal (cFGF23) and an N-terminal fragment. The latter two are seen at significant levels primarily in patients with hyperostosis hyperphosphatemia syndrome (HHS)/ hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (HFTC). HHS and HFTC represent allelic variant disorders of FGF23 processing, in which there is little or no iFGF23 and very high levels of FGF23 degradation products [12]. It is accepted that iFGF23 is the biologically active species in terms of mediating the direct effects on phosphate and vitamin D metabolism; when in excess, cFGF23 has been demonstrated to inhibit the action of iFGF23 [13]. However, questions remain as to whether or not the degradation products of FGF23 have other biological activity [14].

The importance of glycosylation of FGF23 in its function was revealed when mutations in a serine and threonine galactosyl transferase, UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3 (GALNT3), which glycosylates FGF23, were identified as the cause of the allelic hyperphosphatemic disorders HFTC [15] and HHS [12] (Table 1). In vitro studies suggest that glycosylation at T178, the putative SPC consensus sequence, is essential for production and secretion of full length, biologically active FGF23 [12, 16]. Mass spectroscopic analyses revealed several Ser- and Thr- residues present within the 162-228 amino acid region that are O-glycosylated [12] (Fig. 1). However, to date, direct evidence for FGF23 glycosylation in clinical specimens is lacking. HFTC can also arise as the result of mutations in FGF23 (also called HFTC2, [17]), and while many of the mutations in HFTC2 occur at Ser or Thr residues, consistent with the role of FGF23 O-linked glycosylation, others (H41Q, Q54K, and M96T) do not [18]. It has been speculated that in the cases where mutations occur at residues other than Ser or Thr and outside the SPC cleavage site, that protein folding may account for the mechanism of disease.

FGF23 tissue expression profile

FGF23 transcripts exist in the mouse brain, thymus, small intestine and heart, with particularly high expression in the ventrothalamic nucleus of the mouse brain [7]. The ADHR consortium identified transcripts in the human heart, liver, and thyroid/parathyroid [3]. However to date, the data suggest that the only physiologically significant source of FGF23 is the skeleton, osteoblasts and osteocytes. The initial evidence that FGF23 is a bone cell-derived hormone arose from the recognition that the degree of phosphate wasting seen in fibrous dysplasia of bone (FD), an FGF23 excess disorder, correlated with the skeletal disease burden of FD [19], and that high levels of FGF23 transcripts were seen not only in the bone-like cells of FD tissue, but also in normal bone [20]. Subsequently, bone cell expression of FGF23 was confirmed in rodent models [21, 22]. As expected, FGF23 expression has also been identified in cells involved in the mineralization of the teeth, including ameloblasts and odontoblasts [23].

Ectopic production of FGF23 is found in the FGF23 excess disorder of TIO [1, 24, 25]. TIO is the result of tumors histopathologically similar to hemangiopericytomas, that are typically classified as phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors (mixed connective tissue variant) (PMTMCT) [26], but the cells/tissues from which these tumors arise is not clear. In addition, FGF23 excess can be seen in patients with certain pigmented skin lesions, such as linear epidermal nevus syndrome [27] and giant hairy nevus syndrome [28]. However, direct demonstration of FGF23 in these dysplastic tissues has not been demonstrated.

Under normal circumstances, FGF23 circulates in humans and mice in the nM range. The mean ± 1 SD blood levels in humans is 71.8 ± 38.1 RU/mL, (based on detection of intact or C-terminus FGF23) or 29.7 ± 20.7 pg/mL by a more specific assay that measures only iFGF23. Blood levels are approximately the same in children and adults [29]. The FGF23 half-life in humans is between 46-58 min [30]. Levels in mice are slightly higher, 113.7 ± 8.7 pg/mL [31]. The highest levels of FGF23 are seen in renal disease. As the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreases, there is a progressive increase in blood FGF23 levels. When the GFR decreases to the 20-30 mL/min/1.73 m2 range, FGF23 levels can increase up to 5 fold, and in renal failure patients with stage 5 kidney disease levels can be more than 800 fold greater than normal (>59,000 RU/ml) [32-34]. iFGF23 appears to be the primary circulating form in patients renal failure [33]. The increase in blood levels in renal failure are associated with increased FGF23 transcription in bone [31]. Thus, it also appears that bone is the source of FGF23 in renal disease. However, it is possible, but currently not known whether decreased renal clearance and/or impaired renal processing contribute to the increased FGF23 blood levels in renal insufficiency/failure.

FGF23 mechanism of action

The action of FGF23, as demonstrated in various in vitro systems, is mediated by binding to FGF cell-surface receptors including FGFR1, 3c and 4, with FGF23 signaling dependent upon co-expression of a co-receptor, aKL [35, 36]. In this paradigm, FGF23 binds more avidly to FGFRs in the presence of aKL, and triggers intracellular signaling pathways that mediate its biological action. Restricted, tissue-specific action of FGF23, in spite of the broad expression of FGF receptors, seems to derive from the relatively limited expression of aKL to certain tissues including parathyroid, kidney and pituitary [35, 36]. In addition to membrane-bound aKL, the co-receptor also exists in a circulating form. While most evidence points to membrane-bound aKL as the primary mediator of FGF23 activity, circulating aKL is able to transduce FGF23 activity in an in vitro system, albeit at a lower level than the membrane-bound form [36]. FGFs commonly signal through the extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERKs)/Early growth response protein 1 (EGR1) pathway, with the original demonstration of aKL-dependent FGF23 signaling supported by signaling via this pathway [37]. Subsequently, much of the work in the area of FGF23 action was defined by obligate EGR1 signaling. While the multiple models that support aKL-dependent FGF23 signaling as central to the biological action of FGF23 [38] are clearly relevant, dependence upon EGR1 signaling to define FGF23 action may exclude non-EGR1-dependent FGF23 signaling that might also be physiologically relevant.

For example, Faul et al. recently demonstrated in aKL knockout mice, that FGF23 was able to signal via a aKL-independent pathway through the FGFR4/Phospholipase C γ/calcineurin pathway [39]. In this model, at the high concentrations of FGF23, similar to those seen in renal failure, FGF23 was able to induce left ventricular hypertrophy. While awaiting confirmation by other investigators, this suggests a mechanism for the clinically observed, FGF23-depedent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality seen in patients with renal failure [40].

Studies using FGFR3 and FGFR4 knockout mice demonstrated that these receptors are important in the FGF23-mediated renal tubule cell regulation of 1,25-D [41]. However, because the blood calcium level in these mice was not reported, it is difficult to interpret the relevance of these findings to human physiology. The latter point is further emphasized by the fact that humans with mutations in FGFR3 (the underlying cause of achondroplasia and several other skeletal dysplasias), do not have a calcium/vitamin D phenotype. The difficulty in interpreting the findings in the FGFR3 and FGFR4 knockout mice emphasizes the importance of studying and if possible controlling for, the many confounders that exist in the mineral metabolism pathway. Through feedback mechanisms, perturbation of one arm of the mineral metabolism pathway results in obligate changes in other arms, which have the potential to confound the interpretation of the data.

FGF23 action has also been shown to be blunted in patients with hypoparathyroidism, suggesting that full FGF23 action is at least in part PTH-dependent [42]. Indeed, patients with FGF23 excess disorders (TIO and XLH) treated with cinacalcet, a drug that induces hypoparathyroidism by lowering PTH, exhibited blunted FGF23 action [43, 44]. The molecular mechanism of this PTH-dependent FGF23 action with a resultant decrease in urinary phosphate wasting was shown to be mediated via the scaffolding protein NHERF-1, in a PKC/PKA-dependent manner. This suggests that the role of PTH in regulating FGF23-mediated phosphate metabolism involves the established role of NHERF-1 in trafficking NaPi transporters to the cell membrane, and stabilizing PTH receptors in a membrane-bound configuration [45, 46].

FGF23 target tissues

Given the unequivocal role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism and the fact that the majority of phosphate handling and the conversion of inactive 25 hydroxy-vitamin D3 to active 1,25-D takes place at the renal proximal tubule, renal proximal tubule cells are a primary target for the physiologic action of FGF23. Indeed, FGF23 directly regulates, in a coordinated fashion, confirmed by preparations of primary proximal renal tubule cells in vitro [45, 47], the transcription and translation of the proximal renal tubule phosphate-regulating gene type 2a sodium-phosphate co-transporter (NaPi-2a), and the vitamin D-regulating gene, 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-hydroxylase (1α hydroxylase) [48, 49]. However, direct evidence demonstrating both FGFR(s) and aKL expression in proximal tubule cells is lacking. In fact, it is only in distal tubule cells that convincing evidence for the presence of FGFR1, aKL, and FGF23 signaling exists, as evidenced by the presence of P-ERK1/2 and EGR-1 signaling [50]. This apparent paradox could be reconciled by paracrine effects of aKL secreted by the distal tubule cells adjacent proximal tubule cells. However, it is also possible, that FGF23 action on the proximal tubule is neither aKL- nor ERK-dependent.

Klotho is also expressed in parathyroid cells and PTH is a key regulator of mineral homeostasis, making the parathyroid a possible target tissue for FGF23. Animal and in vitro data suggests that FGF23 directly inhibits PTH synthesis and secretion [51, 52]. However, clinical support for the parathyroid as a target of aKL-mediated FGF23 action is indirect; a single patient homozygous for a missense mutation in aKL presented with hyperparathyroidism, and loss of a aKL-dependent inhibitory effect of FGF23 on PTH production was suspected [53]. However, a physiologically significant role for FGF23 in inhibiting PTH synthesis and secretion is lacking in virtually all FGF23 excess disorders including TIO, XLH, and renal failure, where secondary hyperparathyroidism (sometimes leading to tertiary hyperparathyroidism) is a common finding, in the setting of high blood FGF23 levels [25]. The pituitary also shows significant aKL expression, but to date no action of FGF23 on the pituitary has been described.

FGF23 regulation

There is evidence to support independent regulation of FGF23 expression by phosphorus [54-57] and 1,25 D [58, 59], however, the phosphate-sensing mechanism by which FGF23-secreting cells responds to changes in phosphorus remains elusive and might be through an as yet unidentified phosphate sensor. The mechanism by which 1,25-D regulates FGF23 is presumed to be through VDR. There is also evidence that PTH or at least activation of the PTH signaling pathway, as is seen in Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, which is due to activating mutations of the PTH/PTHrP receptor, and in FD, which is due to activating mutations downstream of PTH at Gsα, leads to overexpression of FGF23 [20, 60] (as well as increased processing, discussed below). One would anticipate that study of subjects with primary hyperparathyroidism would offer insight into an effect of PTH on FGF23, but across many studies the data are inconclusive [61-65]. Some studies report a direct effect of PTH on FGF23 levels, and others do not. These inconsistencies are likely explained by several potentially confounding factors: the hypophosphatemic effect of PTH, the relatively elevated 1,25-D in hyperparathyroidism, variable disease severity, and a possible independent effect of hypercalcemia.

Important differences exist in how FGF23 is regulated in normal subjects and subjects with metabolic bone diseases, versus those with renal insufficiency and renal failure. What regulates the very high blood levels seen in renal disease is not clear. While levels of FGF23 in late renal disease correlate with serum phosphorus, FGF23 levels begin to rise before there is an increase in serum phosphorus (and/or PTH), in early stages of renal failure, suggesting that initially there is a primary phosphorus- and PTH-independent regulation of FGF23 in mild renal insufficiency [32]. It is also unlikely that the degree of elevation of FGF23 seen in renal failure is explained by hyperphosphatemia alone. This degree of elevation of FGF23 is not seen in the patients with familial tumoral calcinosis (FTC), some of whom have a similar degree of hyperphosphatemia, but do not have the degree of elevation of FGF23 that is seen in renal failure [17, 66-68]. And while loss of renal clearance of FGF23 remains a possibility as a contributor, it too does not offer a satisfactory explanation. Clearly there is a primary, direct stimulatory process in place in patients with renal failure that remains to be identified.

Three monogenic hypophosphatemic disorders in which dysregulated FGF23 remains inadequately explained are autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (AHRH1), caused by mutations in the extracellular matrix protein, dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP-1) [69, 70], XLH, caused by mutations in the transmembrane endopeptidase known as phosphate regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X chromosome (PHEX) [71], and ARHR2, caused by mutations in ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP-1) [72] (Table 1). There is speculation that all of these, through unclear mechanisms, lead to local (peri-osteocyte) under-mineralization, and (counter intuitively) over production of FGF23 [73].

An exciting and important area of investigation that is emerging and awaits further confirmation is in a potential role for iron in the regulation of FGF23. Durham et al. detected an elevated C-terminal FGF23 level in three subjects with low ferritin (and therefore probably iron deficiency anemia). They made the observation that in subjects who were most likely iron deficient, there were elevated levels of cFGF23, but normal levels of iFGF23 [74], thus offering the first suggestion of a role for iron in FGF23 metabolism and hinting that FGF23 processing may be involved in regulation of iFGF23 levels. Subsequent work showed that iron infusions leads to FGF23-mediated hypophosphatemia [75-77].

Further studies in ADHR also support an iron/FGF23 interaction. Imel et al. noted a significant negative correlation between both iFGF23 and cFGF23 levels and serum iron levels in subjects with ADHR [78]. However, in normal controls there was no correlation between iFGF23 and iron, but there was a negative correlation between cFGF23 and iron. Farrow et al. further explored this using an ADHR mouse model, and an osteoblast cell line [79]. ADHR mice fed an iron deficient diet had elevations of both intact and cFGF23, and wild type mice on the same diet showed normal iFGF23 but a marked 5-fold elevation in cFGF23. In addition, treatment of the rat osteoblastic cell line UMR-106 with the iron chelator deferoxamine increased FGF23 mRNA, suggesting a stimulatory effect of iron deficiency on FGF23 production.

While these studies leave us with a clear sense that iron is involved in FGF23 regulation, they also reveal an apparent paradox – both iron infusion and iron deficiency appear to stimulate FGF23 production. Resolution of this paradox will require a better understanding of the roles of iron-related/iron-sensing pathways in bone cell FGF23 regulation (hypoxia/HIF, BMP6/hepcidin), as well as understanding the role for FGF23 processing in the overall regulation of intact, active FGF23 levels. A role for osteoblast HIF signaling has recently emerged that may help us begin to understand the relationship between iron homeostasis and FGF23 homeostasis [80].

FGF23 processing

The discovery of mutations at the SPC site in FGF23, which cause resistance to SPC-mediated enzymatic degradation/processing [3], and mutations in the enzyme GALNT3 [15], which result in increased FGF23 degradation/processing of FGF23, suggest that processing of FGF23 is a physiologically important process that regulates intact, functional FGF23 levels. This is supported by observations in FD, a disease in which patients have high levels of “total” (both C-terminal degradation products + intact) FGF23, but relatively lower levels of iFGF23 [81]. In bone cells from patients with FD, which is caused by mutations in Gsα that result in altered cAMP signaling, the enzyme activity of the SPC furin is increased and GALNT3 decreased in a cAMP-dependent manner, leading to an increase in the cFGF23 to iFGF23 ratio. The generation of relatively greater cFGF23 in FD may reflect a physiologic compensation to guard against the effects of excess iFGF23, as excess of cFGF23 has been shown to block the action iFGF23 [13].

Altered FGF23 processing via an iron/hypoxia-dependent pathway may explain the recent observations in both patients with ADHR [82] and an ADHR mouse model [79]. It appears that iron deficiency results in a marked increase in FGF23 transcription and translation, but that both normal human subjects and wild type mice are able to evade the development of hypophosphatemia by increasing FGF23 processing, which is evidenced by normal levels of iFGF23, but increased levels of cFGF23. An untested explanation for this observation would be that iron deficiency results in an imbalance between GALNT3 and SPC (furin) activity, such that there is relatively less GALNT3 activity and relatively greater furin activity in anemia. There is clear evidence in hepatocytes that iron deficiency results in increased furin levels [83]; this may also be the case in FGF23-producing cells. Anemic patients have high levels of FGF23 transcription, translation, and processing. It is thus enticing to speculate that the increase in iFGF23 and hypophosphatemia that was observed when anemic patients received iron infusions [75-77] may be the result of suppressed FGF23 cleavage due to iron-mediated inhibition of furin activity. By this model, furin-mediated FGF23 processing would be increased in the iron deficient state to guard against hypophosphatemia.

There appears to be little if any FGF23 processing in renal failure, as virtually all of the FGF23 in blood (as assessed by Western blot) appears to be intact [33]. This is a surprising finding, given the marked elevations in blood levels and the potential for a prolonged half-life due to lack of possible renal clearance.

Concluding remarks

Two of the most active areas of investigation in FGF23 biology that will likely yield insight over the next few years and might lead to possible novel therapeutics, are the related fields of the role of iron in FGF23 physiology and FGF23 processing. If FGF23 processing could be manipulated, with inhibitors of GALNT3 for example, one could induce FGF23 processing in renal failure and other diseases of FGF23 excess and convert intact FGF23 into inactive fragments. Given that renal failure is a disease of significant public health impact, and that there is evidence that elevated FGF23 is an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality [40], targeted therapies for FGF23 excess disorders are needed.

A central challenge in studying FGF23 biology in the future will be dissecting and understanding the differences between non-renal and renal FGF23 physiology. What we have learned from the rare, monogenic disorders of FGF23-related disease has taken us far. However, in the case of the much more common disease of renal failure and renal insufficiency, the physiology is different. Given that survival after renal failure is a phenomenon of the last 60 years of so, it is likely that at least some of the pathophysiologic mechanisms operative in patients with renal failure are not evolutionarily derived and that new thinking and approaches will be needed.

Other questions that remain to be answered are: what is the role of FGF23 in “normal” individuals, and do differences in FGF23 levels within the normal range have an impact on health? Two studies suggest they do. Mirza et al. studied normal community dwelling subjects [84] and Parker et al. those with stable coronary artery disease [85]. Both found that even among subjects that had FGF23 levels within the normal range, those with the highest FGF23 levels had either evidence of vascular dysfunction [84] or increased cardiovascular mortality [85]. In fact, Parker et al. found a striking two-fold increase in mortality between those in the highest and lowest FGF23 tertiles. While the analytic techniques used in this paper attempted to control for relevant confounders, the supplemental data revealed that subjects who died had a significantly higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors.

Finally, what is the role of the FGF23 physiology in the maintenance of bone health in “normal” individuals? Are there subtle differences in the set points of the FGF23/phosphorus/vitamin D pathway in certain populations that can account for differences in fracture risk, similar to the differences seen in the PTH/vitamin D/calcium pathway between blacks and whites and which are thought to contribute to differences in fracture risk between the two [86-89]? An analysis of the > 3,000 elderly men in the Swedish part of the population-based Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study suggest yes [90]. Even when renal function is controlled for, men with FGF23 levels in the highest quartile had a significantly increased risk of fractures. A better understanding of FGF23 physiology in relationship to fracture risk in the absence of a primary “disease” of mineral metabolism may better explain a significant portion of idiopathic fractures and have a significant impact on public health.

The next several years will undoubtedly see advances in our understanding of FGF23 in health and disease. The areas of investigation likely to have the greatest yield are studies in FGF23 processing, the role of the iron/hypoxia pathway in the regulation of FGF23, a better understanding of differences between FGF23 physiology in renal and non-renal disease, and the role of FGF23 in the risk of cardiovascular disease and fractures.

Figure 2. FGF23 synthesis, secretion, processing, and action.

A) FGF23 is produced by bone cells (primarily osteocytes and osteoblasts), circulates in the blood and acts on the kidney to induce phosphaturia, by lowering blood phosphorus levels, and inhibiting the production of the active vitamin D metabolite 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D3 (1,25 D). This has the negative feedback effect of decreasing bone FGF23 production. B) FGF23 acts at renal tubule cells by binding to an FGF receptor (FGFR – most likely FGFR1) and its co-receptor Klotho to activate the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase/ extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1/2 pathway and decrease the transcription, translation and overall activity of the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-hydroxylase (1 α hydroxylase), which converts inactive vitamin D to active 1,25-D. Receptor biding also increases phosphate transport into the urine via the sodium-dependent phosphate transporters 2a and c (NaPi2a/c). The latter action partly depends upon the coordinated activity with parathyroid hormone receptor/parathyroid related protein receptor (PTH/PTHrP-R) stimulated activity of Na/H exchange regulatory factor-1 (NHERF1), which is a PDZ domain scaffolding protein that may function to stabilize the PTH/PTHrP-R and NaPi2c in a signaling configuration via the protein kinase C/protein kinase A (PKC/PKA) pathway. C) Osteocytes and osteoblasts are the source of FGF23. In response to elevations in phosphorus and 1,25 D (and to some extent further stimulated by activation of the PTH/cAMP pathway), FGF23 transcription, translation, and secretion are stimulated. There is evidence that iron has an impact on FGF23 levels, which may be by a direct effect on bone cell FGF23 production. The mechanism by which it does, and the way in which it does, remain to be defined. D) FGF23 processing is carried out by the enzymatic activity of the enzymes polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3 (GALNT3) and a subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (SPC), probably furin. The overall level of intact, biologically active FGF23 in the circulation is a reflection of the overall activity of GALNT3 and furin. In the absence of glycosylation by GALNT3, FGF23 is cleaved by furin and only the processed, N-terminal (N-term.) and C-terminal (C-term.) degradation products, which are not biologically active, are secreted. The enzyme activity of both GALNT3 and furin are regulated by cAMP. There is emerging evidence, through an as yet undefined mechanism, that iron too may be able to regulate GALNT3 and/or furin activity.

Figure 3. FGF23 in Renal Disease.

A) In renal disease, very high levels of FGF23 are produced by bone cells, resulting in blood levels of FGF23 that can be up to 1,000 times greater than normal. The mechanism by which these very high levels are produced is not known. A “renal” factor possibly exists, which may or may not be produced by the kidney, and which contributes to the high levels produce in renal disease. B) In a rodent model, there is a single report that at the very high levels seen in renal failure, FGF23 has been shown to act directly on cardiac myocytes by binding to FGFR4 in a Klotho-independent manner via the phospholipase C/calcineurin pathway. C) FGF23 production by bone cells probably occurs under the stimulation of hyperphosphatemia and the administration of 1,25-D that is common in patients with renal failure. However, this alone is not enough to account for the changes that are seen, as FGF23 begins to rise even before blood phosphorus levels rise. There is even a period during which blood phosphorus levels decrease below baseline as FGF23 rises, suggesting that high phosphorus alone is not necessary the primary stimulus. All of this suggests there is physiology involved in the regulation of FGF23 that is unique to renal disease, termed here as a “renal factor.” D) It appears that virtually all the FGF23 seen in the circulation in renal failure is intact FGF23, suggesting that there is little if any processing of intact FGF23 to the C- or N-terminal products. Processing may be inhibited by hyperphosphatemia or an as yet unidentified renal factor pathway.

TEXT BOX 1. Recognition of the existence of a phosphaturic factor.

Perhaps the first recognition of the existence of a circulating factor that regulates phosphate metabolism can be attributed to Andrea Prader [1]. In 1959, he reported the case of an 11 ½ year old girl who presented with an acquired disorder of hypophosphatemia, renal phosphate wasting and rickets that resolved after surgical excision of a benign mixed connective tissue tumor from the rib. Prader recognized the likely cause was a “rachitogenic substance” secreted by the tumor – thus describing what we now know to be a case of Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23-mediated tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO). The first convincing experimental evidence in support of the existence of a phosphaturic factor was supplied by the elegant work of Ralph Meyer and colleagues [2]. Parabiosis experiments performed in hyp mice, an animal model for the FGF23 excess phosphaturic disorder X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), demonstrated that a circulating factor in the hyp mouse not only induced hypophosphatemia, but also inhibited 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D3 (1,25-D) production – supplying the first evidence for the existence of a phosphate- and vitamin D-regulating hormone. However, it was not until 2000, when mutations in FGF23 were identified as the cause of autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) [3], that FGF23 was recognized as a protein central in hypophosphatemic disorders and mineral metabolism. Shortly thereafter, alterations in blood FGF23 were seen in multiple hypophosphatemic and hyperphosphatemic disorders [4-6] (Table 1).

Acknowledgments

Support: This research was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services

Footnotes

Conflicts: The authors have no financial or ethical conflicts

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prader A, et al. Rickets following bone tumor. Helvetica paediatrica acta. 1959;14:554–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer RA, Jr, et al. Parabiosis suggests a humoral factor is involved in X-linked hypophosphatemia in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4:493–500. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ADHR C. Nat Genet. Vol. 26. The ADHR Consortium; 2000. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23; pp. 345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimada T, et al. Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6500–6505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101545198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber TJ, et al. Serum FGF23 levels in normal and disordered phosphorus homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1227–1234. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.7.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benet-Pages A, et al. An FGF23 missense mutation causes familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2004 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita T, et al. Identification of a novel fibroblast growth factor, FGF-23, preferentially expressed in the ventrolateral thalamic nucleus of the brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:494–498. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is a counter-regulatory phosphaturic hormone for vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1305–1315. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barthel TK, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3/VDR-mediated induction of FGF23 as well as transcriptional control of other bone anabolic and catabolic genes that orchestrate the regulation of phosphate and calcium mineral metabolism. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2007;103:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamazaki Y, et al. Anti-FGF23 neutralizing antibodies show the physiological role and structural features of FGF23. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1509–1518. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goetz R, et al. Molecular insights into the klotho-dependent, endocrine mode of action of fibroblast growth factor 19 subfamily members. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:3417–3428. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02249-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frishberg Y, et al. Hyperostosis-hyperphosphatemia syndrome: a congenital disorder of O-glycosylation associated with augmented processing of fibroblast growth factor 23. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:235–242. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetz R, et al. Isolated C-terminal tail of FGF23 alleviates hypophosphatemia by inhibiting FGF23-FGFR-Klotho complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berndt T, et al. Evidence for a signaling axis by which intestinal phosphate rapidly modulates renal phosphate reabsorption. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11085–11090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704446104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topaz O, et al. Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:579–581. doi: 10.1038/ng1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato K, et al. Polypeptide GalNAc-transferase T3 and familial tumoral calcinosis. Secretion of fibroblast growth factor 23 requires O-glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18370–18377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergwitz C, et al. Defective O-glycosylation due to a novel homozygous S129P mutation is associated with lack of fibroblast growth factor 23 secretion and tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4267–4274. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chefetz I, Sprecher E. Familial tumoral calcinosis and the role of O-glycosylation in the maintenance of phosphate homeostasis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1792:847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins MT, et al. Renal phosphate wasting in fibrous dysplasia of bone is part of a generalized renal tubular dysfunction similar to that seen in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:806–813. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riminucci M, et al. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:683–692. doi: 10.1172/JCI18399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sitara D, et al. Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypophosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirams M, et al. Bone as a source of FGF23: regulation by phosphate? Bone. 2004;35:1192–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onishi T, et al. Phex mutation causes overexpression of FGF23 in teeth. Archives of oral biology. 2008;53:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Q, et al. Brief report: inhibition of renal phosphate transport by a tumor product in a patient with oncogenic osteomalacia. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1645–1649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chong WH, et al. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Endocrine-related cancer. 2011;18:R53–77. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folpe AL, et al. Most osteomalacia-associated mesenchymal tumors are a single histopathologic entity: an analysis of 32 cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1–30. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sethi SK, et al. Elevated FGF-23 and parathormone in linear nevus sebaceous syndrome with resistant rickets. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1577–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyce AM, et al. A Novel Syndrome of Neurocutaneous Melanosis, Hypophosphatemic Rickets, and a Mosaic Skeletal Dysplasia. Endocr Rev. 2011;32:2–162. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imel EA, et al. Sensitivity of fibroblast growth factor 23 measurements in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2055–2061. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosravi A, et al. Determination of the elimination half-life of fibroblast growth factor-23. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2374–2377. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stubbs JR, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of FGF23 changes and mineral metabolism abnormalities in a mouse model of chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1370–1378. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimada T, et al. Circulating Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease Treated by Peritoneal Dialysis Is Intact and Biologically Active. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson T, et al. Circulating concentration of FGF-23 increases as renal function declines in patients with chronic kidney disease, but does not change in response to variation in phosphate intake in healthy volunteers. Kidney Int. 2003;64:2272–2279. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urakawa I, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature05315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurosu H, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6120–6123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500457200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Urakawa I, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature05315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Razzaque MS. The FGF23-Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nature reviews. 2009;5:611–619. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faul C, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4393–4408. doi: 10.1172/JCI46122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutierrez OM, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gattineni J, et al. Regulation of serum 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 levels by fibroblast growth factor 23 is mediated by FGF receptors 3 and 4. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F371–377. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00740.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta A, et al. FGF-23 is elevated by chronic hyperphosphatemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4489–4492. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geller JL, et al. Cinacalcet in the management of tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:931–937. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alon US, et al. Calcimimetics as an adjuvant treatment for familial hypophosphatemic rickets. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:658–664. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04981107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinman EJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23-mediated inhibition of renal phosphate transport in mice requires sodium-hydrogen exchanger regulatory factor-1 (NHERF-1) and synergizes with parathyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37216–37221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.288357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahon MJ, et al. Na(+)/H(+) exchanger regulatory factor 2 directs parathyroid hormone 1 receptor signalling. Nature. 2002;417:858–861. doi: 10.1038/nature00816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baum M, et al. Effect of fibroblast growth factor-23 on phosphate transport in proximal tubules. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1148–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimada T, et al. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimada T, et al. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:561–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrow EG, et al. Initial FGF23-mediated signaling occurs in the distal convoluted tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:955–960. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ben-Dov IZ, et al. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:4003–4008. doi: 10.1172/JCI32409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krajisnik T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 regulates parathyroid hormone and 1alpha-hydroxylase expression in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. The Journal of endocrinology. 2007;195:125–131. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ichikawa S, et al. A homozygous missense mutation in human KLOTHO causes severe tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2684–2691. doi: 10.1172/JCI31330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Antoniucci DM, et al. Dietary phosphorus regulates serum fibroblast growth factor-23 concentrations in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3144–3149. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burnett SA, et al. Regulation of C-terminal and intact FGF-23 by dietary phosphate in men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1187–1196. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferrari SL, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 relationship to dietary phosphate and renal phosphate handling in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1519–1524. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu X, et al. Genetic dissection of phosphate- and vitamin D-mediated regulation of circulating Fgf23 concentrations. Bone. 2005;36:971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Collins MT, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 is regulated by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1944–1950. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kolek OI, et al. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: the final link in a renal-gastrointestinal-skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G1036–1042. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00243.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown WW, et al. Hypophosphatemia with elevations in serum fibroblast growth factor 23 in a child with Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:17–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh RJ, Kumar R. Fibroblast growth factor 23 concentrations in humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy and hyperparathyroidism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:826–829. doi: 10.4065/78.7.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tebben PJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23, parathyroid hormone, and 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in surgically treated primary hyperparathyroidism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1508–1513. doi: 10.4065/79.12.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kobayashi K, et al. Regulation of plasma fibroblast growth factor 23 by calcium in primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:93–99. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kawata T, et al. Parathyroid hormone regulates fibroblast growth factor-23 in a mouse model of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2683–2688. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mosekilde L. Primary hyperparathyroidism and the skeleton. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benet-Pages A, et al. An FGF23 missense mutation causes familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:385–390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chefetz I, et al. A novel homozygous missense mutation in FGF23 causes Familial Tumoral Calcinosis associated with disseminated visceral calcification. Hum Genet. 2005;118:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dumitrescu CE, et al. A case of familial tumoral calcinosis/hyperostosis-hyperphosphatemia syndrome due to a compound heterozygous mutation in GALNT3 demonstrating new phenotypic features. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1273–1278. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0775-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng JQ, et al. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lorenz-Depiereux B, et al. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/ng1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Consortium TH. A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. The HYP Consortium. Nat Genet. 1995;11:130–136. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levy-Litan V, et al. Autosomal-recessive hypophosphatemic rickets is associated with an inactivation mutation in the ENPP1 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quarles LD. Skeletal secretion of FGF-23 regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. Nature reviews. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Durham BH, et al. The association of circulating ferritin with serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor-23 measured by three commercial assays. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2007;44:463–466. doi: 10.1258/000456307781646102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schouten BJ, et al. Iron polymaltose-induced FGF23 elevation complicated by hypophosphataemic osteomalacia. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2009;46:167–169. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.008151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schouten BJ, et al. FGF23 elevation and hypophosphatemia after intravenous iron polymaltose: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2332–2337. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shimizu Y, et al. Hypophosphatemia induced by intravenous administration of saccharated ferric oxide: another form of FGF23-related hypophosphatemia. Bone. 2009;45:814–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Imel EA, et al. Iron modifies plasma FGF23 differently in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets and healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3541–3549. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farrow EG, et al. Iron deficiency drives an autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) phenotype in fibroblast growth factor-23 (Fgf23) knock-in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110905108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rankin EB, et al. The HIF signaling pathway in osteoblasts directly modulates erhytropoesis through the production of EPO. Cell. 2012;149:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhattacharyya N, et al. Mechanism of FGF23 processing in fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Imel EA, et al. Iron Modifies Plasma FGF23 Differently in Autosomal Dominant Hypophosphatemic Rickets and Healthy Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Knutson MD. Iron-sensing proteins that regulate hepcidin and enteric iron absorption. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:149–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mirza MA, et al. Circulating fibroblast growth factor-23 is associated with vascular dysfunction in the community. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parker BD, et al. The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Annals of internal medicine. 2010;152:640–648. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fuleihan GE, et al. Racial differences in parathyroid hormone dynamics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1642–1647. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.6.7989469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bell NH, et al. Tight regulation of circulating 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in black children. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511283132216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bell NH, et al. Demonstration of a difference in urinary calcium, not calcium absorption, in black and white adolescents. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1111–1115. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cosman F, et al. Resistance to bone resorbing effects of PTH in black women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:958–966. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mirza MA, et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) and fracture risk in elderly men. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:857–864. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carpenter TO, et al. A clinician’s guide to X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1381–1388. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Turan S, et al. Identification of a novel dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP-1) mutation and dental anomalies in a kindred with autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia. Bone. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lorenz-Depiereux B, et al. Loss-of-function ENPP1 mutations cause both generalized arterial calcification of infancy and autosomal-recessive hypophosphatemic rickets. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mehta P, et al. Novel compound heterozygous mutations in ENPP1 cause hypophosphataemic rickets with anterior spinal ligament ossification. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saito T, et al. A patient with hypophosphatemic rickets and ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament caused by a novel homozygous mutation in ENPP1 gene. Bone. 2011;49:913–916. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Holm IA, et al. Mutational analysis of the PEX gene in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:790–797. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jan de Beur SM. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Jama. 2005;294:1260–1267. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dumitrescu CE, Collins MT. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2008;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Collins MT, et al. McCune-Albright syndrome and the extraskeletal manifestations of fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2012;7(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.White KE, et al. Mutations that cause osteoglophonic dysplasia define novel roles for FGFR1 in bone elongation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:361–367. doi: 10.1086/427956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Narchi H. Hyperostosis with hyperphosphatemia: evidence of familial occurrence and association with tumoral calcinosis. Pediatrics. 1997;99:745–748. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Frishberg Y, et al. Identification of a recurrent mutation in GALNT3 demonstrates that hyperostosis-hyperphosphatemia syndrome and familial tumoral calcinosis are allelic disorders. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2005;83:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]