Abstract

Clostridium difficile strains were sampled periodically from 50 animals at a single veal calf farm over a period of 6 months. At arrival, 10% of animals were C. difficile positive, and the peak incidence was determined to occur at the age of 18 days (16%). The prevalence then decreased, and at slaughter, C. difficile could not be isolated. Six different PCR ribotypes were detected, and strains within a single PCR ribotype could be differentiated further by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The PCR ribotype diversity was high up to the animal age of 18 days, but at later sampling points, PCR ribotype 078 and the highly related PCR ribotype 126 predominated. Resistance to tetracycline, doxycycline, and erythromycin was detected, while all strains were susceptible to amoxicillin and metronidazole. Multiple variations of the resistance gene tet(M) were present at the same sampling point, and these changed over time. We have shown that PCR ribotypes often associated with cattle (ribotypes 078, 126, and 033) were not clonal but differed in PFGE type, sporulation properties, antibiotic sensitivities, and tetracycline resistance determinants, suggesting that multiple strains of the same PCR ribotype infected the calves and that calves were likely to be infected prior to arrival at the farm. Importantly, strains isolated at later time points were more likely to be resistant to tetracycline and erythromycin and showed higher early sporulation efficiencies in vitro, suggesting that these two properties converge to promote the persistence of C. difficile in the environment or in hosts.

INTRODUCTION

An increasing number of reports have focused on the prevalence and shedding of Clostridium difficile in domestic animals, especially pigs, cattle, other food animals, and horses (1, 2, 11, 12, 17, 18, 20, 28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 37, 44, 47). In cattle and pigs, PCR ribotype 078 (type 078) has frequently been identified as predominant (11, 12, 15, 16, 25, 44). More recently, this type has also been considered an important pathogen in humans and has been detected in different countries (5, 14, 21, 24, 36). In 2005, type 078 was the 11th most frequent type isolated from humans in Europe (4), becoming the 3rd most frequent PCR ribotype in 2009 (5). Interestingly, human and pig type 078 isolates have been shown to be closely related (3, 24). Therefore, type 078 has been speculated to be a new emerging strain associated with increased virulence and could be an example of interspecies food-borne transmission of C. difficile (38, 43, 45).

Few longitudinal screenings of C. difficile in swine (20, 44), poultry (47), or cattle (11, 33) facilities have been published. For cattle, one study followed the colonization and prevalence of tetracycline resistance in a single veal farm in Canada (11), while another study included older animals at a finishing facility and also looked at the prevalence of C. difficile, on-farm transmission, and contamination at slaughter (33).

The primary objective of this study was to assess the presence of certain genotypes of C. difficile in veal calves and their prevalences at different time points in the production cycle. Additionally, isolates were characterized in terms of antibiotic resistance determinants and sporulation properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

The veal production cohort in Belgium consisted of 340 Belgian Blue/Holstein Friesian crossbreed veal calves. Calves arrived at the veal herd when they were 14 days old. The calves were housed within compartments of 112 animals on slatted floors. For the first 6 weeks, the animals were housed individually, and thereafter, 5 or 6 animals were grouped per pen. The animals received a low-iron milk powder diet, concentrates, and roughage replacer twice daily. The calves received colistin (0.5 g twice daily [BID]) (Promycin; VMD) and amoxicillin (1 g BID) (80% Dokamox; Emdoka) for 10 days, starting on day 7 after arrival. For prevention of diarrhea, all animals received enrofloxacin on day 5 after arrival (0.25 g/calf, administered once) (2.5% Baytril oral solution; Bayer). As a metaphylactic treatment for respiratory disease, doxycycline was administered (0.5 g BID) (50% Doxyveto pulvis; VMD) for 5 days, and tylosin was administered for 7 days (0.5 g BID) (Tylan; Eli Lilli) (from day 13 after arrival). All individual treatments in the first 2 months after arrival were individually recorded by the owner (indication, drug, dose, and route of administration).

Sampling was carried out between February and August 2010, on six different occasions, at the calf ages of 14 (at arrival), 18, 25, 32, and 46 days and just before slaughter (194 days). Within a single compartment, a total of 50 calves (arrived on the same day) were randomly selected and individually identified with ear tags. The rectal temperature was first recorded. As sampling was done shortly after the morning meal, most calves spontaneously defecated after rectal stimulation with the thermometer. The thermometer was disinfected with 97% alcohol, and gloves were replaced after each calf. Only if an animal did not defecate spontaneously, the swab was introduced into the rectum and rotated. Rectal swabs were taken maximally for two animals per sampling point. Only at sampling point 4, 13 of 50 animals (26%) were sampled by rectal swabs. Fecal samples were scored as normal (firm), pasty diarrhea, watery diarrhea, or clay-like feces (sign of ruminal drinking). Samples were collected by submerging a swab into the middle of the feces and then placing it into a recipient tube. During shipping (1 to 2 days), swabs were held at room temperature, and they were processed immediately upon arrival at the laboratory.

C. difficile isolation.

Swabs were placed into CDA enrichment broth (C. difficile agar, without agar; Oxoid) supplemented with C. difficile selective supplement (SR0096E; Oxoid) and germination enhancers (0.1% sodium cholate and 5 mg/liter of lysozyme) and then incubated for 5 to 7 days. Subsequently, 500 μl of enriched culture was used for alcohol shock at a volume ratio of 1:1 for 30 min at room temperature. Pellets were inoculated on commercial selective Clostridium difficile agar plates (CLO; bioMérieux) and incubated for 3 days. For several samples (n = 11), 1 to 4 colonies with typical C. difficile morphology were randomly collected from a single CLO plate and further subcultured on Columbia agar plates with 5% horse blood (COH; bioMérieux). Identification was confirmed by C. difficile-specific PCR as described previously (47).

Molecular typing of C. difficile strains.

Toxinotyping was done by PCR amplification and restriction analysis of A3 and B1 fragments of the tcdA and tcdB genes as previously described (35; www.mf.uni-mb.si/mikro/tox). The binary toxin gene was detected by partial amplification of cdtB (41).

PCR ribotyping was performed by using the primers and conditions described by Bidet et al. (6). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using the SacII restriction endonuclease was used as described elsewhere (22). If the strain could not be typed by the standard protocol, electrophoresis was modified by addition of 180 μl of 1 M urea to 2.4 liters of electrophoresis buffer (13).

Both PCR ribotype and PFGE results were analyzed using BioNumerics software (version 5.10; Applied Maths). To show similarity between PFGE patterns, dendrograms were made by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages, using Dice coefficients with position tolerance and an optimization of 1.1%. Clusters with <92% similarity were considered to represent distinct PFGE types, and clusters with ≥92% similarity represented distinct subtypes within one PFGE type.

Antibiotic resistance testing.

From C. difficile cultures grown on Columbia agar plates with 5% horse blood (COH; bioMérieux) for 48 h, suspensions reciprocal to a 1 McFarland standard were prepared and inoculated on brucella blood agar plates supplemented with hemin (5 mg/liter) and vitamin K1 (1 mg/liter). Etest strips containing doxycycline, erythromycin, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and metronidazole (AB bioMérieux) were applied to the agar surface, and plates were incubated in anaerobic jars for 48 h. Resistance was defined at the following breakpoints reported by Barbut et al. (4) and the CLSI (9a): metronidazole, ≥32 mg/liter; tetracycline, ≥8 mg/liter; doxycycline, ≥8 mg/liter; amoxicillin, ≥2 mg/liter; and erythromycin, ≥4 mg/liter. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ATCC 29741 was used as a quality control strain.

Characterization of antibiotic resistance determinants.

DNAs from strains which were tetracycline resistant were used as templates in PCRs with primers RPP-F and RPP-R (42), which were designed to amplify a region of ribosomal protection protein (RPP) genes, including tet(M), tet(S), tet(W), tet(32), and tet(O). Each sample giving a positive result was used in two further PCRs, and all three amplicons (from each template) were cleaned and sequenced to provide unambiguous triple coverage. These consensus sequences derived from each isolate were trimmed to give 1 kb of sequence and were analyzed in three ways. First, all tetracycline resistance gene fragments from a single animal at a single time point were compared. Second, all isolates from a single animal at every time point were compared. Finally, all isolates from all animals at a single time point were compared using BioEdit in order to identify any differences. Phylogenetic alignments were carried out using the ClustalW2 multiple-sequence alignment tool (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/).

Sporulation assays.

Altogether, 13 C. difficile strains were selected in a way to include representatives of different genotypes isolated throughout the sampling points. Growth and sporulation were carried out in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium at 37°C under anaerobic conditions (5% H2, 15% CO2, 80% N2) in a glove chamber. Overnight cultures of each strain grown in 5 ml of BHI medium were used to inoculate 20 ml of fresh BHI medium at a dilution of 1:100.

Samples (100 μl) were withdrawn 24 and 72 h after inoculation. Serial dilutions were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (8 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl) and plated before (total cell count) and after (heat-resistant cell count) heat treatment for 30 min at 60°C (19). Samples were plated on BHI agar supplemented with 0.1% taurocholic acid (Roth) to ensure efficient spore germination (39, 46). The frequency of sporulation is defined as the percentage of the heat-resistant count relative to the total cell count. Three independent experiments were performed for each strain.

RESULTS

Prevalence of C. difficile and association with symptoms.

A total of 300 samples were collected from 50 animals on six different occasions (Table 1). Of all 300 tested samples, 21 (7.0%) were C. difficile culture positive. Because more than one colony was subcultured from several samples, the final number of isolates obtained from 21 positive samples was 38 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of C. difficile in a group of 50 veal calves at six sampling points

| Sampling point | Age (days) of calves at sampling point | No. of C. difficile-positive samples/no. of collected samples (%) | Total no. of isolates collected | C. difficile 078 and 126 typesa | Other C. difficile typesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (at arrival) | 14 | 5/50 (10.0) | 7 | V/078/C4b (1/7), V/078/C5 (1/7) | V/045/C8 (2/7), XI/033/C2 (1/7), XI/033/C1 (1/7), XI/033/C3 (1/7) |

| 2 | 18 | 8/50 (16.0) | 12 | V/078/C4b (2/12), V/078/C5 (2/12), V/126/C4a (2/12), V/126/C10 (2/12) | V/045/C8 (2/12), tox−/010/C12 (1/12), tox−/010/nt (1/12) |

| 3 | 25 | 6/50 (12.0) | 12 | V/078/C4b (4/12), V/078/C9 (2/12), V/126/C4a (2/12), V/126/C6 (2/12), V/126/C11 (1/12) | 0/012/C7 (1/12) |

| 4 | 32 | 1/50 (2.0) | 3 | V/126/C10 (1/3) | 0/012/C7 (2/3) |

| 5 | 46 | 1/50 (2.0) | 4 | V/126/C6 (4/4) | None |

| 6 | 194 | 0/50 (0.0) | 0 | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Total | 21/300 (7) | 38 | 26 | 12 |

Toxinotype/PCR ribotype/PFGE type (number of isolates with type/number of isolates detected). nt, not typeable by PFGE.

Altogether, 15 of 50 monitored calves were positive for C. difficile at least once (calves A to O) (Table 2). During the first five sampling points, the prevalences of C. difficile-positive animals ranged from 2% to 16%. The highest colonization rate (16%) was observed when the calves were 18 days old. This was followed by a considerable decrease in detection. At the last (sixth) sampling point, all 50 calves were negative for C. difficile (Table 1).

Table 2.

Distribution of isolated C. difficile strains in positive animals at different sampling pointsa

| Calf | Description of isolate(s) at sampling point (calf age) [strain-toxinotype/PCR ribotype/PFGE type/type of tet(M) determinant-antibiotic resistance] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (14 days) | 2 (18 days) | 3 (25 days) | 4 (32 days) | 5 (46 days) | |

| A | S21-V/126/C4a/tet(M)12-Ermr, S22-V/126/C4a/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr | ||||

| B | S36-tox−/010/C12-Ermr, S5-tox−/010/nt-Ermr | ||||

| C | S14-V/126/C4a/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr, S15-V/126/C4a/tet(M)11-Tetr Ermr | ||||

| D | S34-XI/033/C3/tet(M)9-Tetr, S1-V/045/C8, S35-V/045/C8 | S6-V/045/C8 | |||

| E | S12-V/078/C5 | S7-V/078/C5, S16-V/078/C5 | |||

| F | S2-XI/033/C2/tet(M)10-Tetr | ||||

| G | S3-XI/033/C1/tet(M)11 | ||||

| H | S13-0/012/C7/tet(M)8-Tetr Ermr Dcr | S9-0/012/C7/tet(M)8-Tetr Ermr Dcr, S38-0/012/C7/tet(M)8-Tetr Ermr Dcr, S10-V/126/C10/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr | |||

| I | S23-V/078/C4b/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr, S24-V/078/C4b/tet(M)11-Tetr Ermr | ||||

| J | S37-V/045/C8 | ||||

| K | S17-V/078/C4b/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr | ||||

| L | S18-V/126/C10/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr, S19-V/126/C10/tet(M)7-Ermr | ||||

| M | S25-V/126/C6/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr | S11-V/126/C6/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr, S31-V/126/C6/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr, S32-V/126/C6/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr, S33-V/126/C6/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr | |||

| N | S26-V/126/C6/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr, S29-V/126/C11/tet(M)7-Tetr Ermr, S27-V/078/C9/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr, S28-V/078/C9/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr | ||||

| O | S4-V/078/C4b/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr | S20-V/078/C4b/tet(M)12-Ermr | S8-V/078/C4b/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr, S30-V/078/C4b/tet(M)12-Tetr Ermr | ||

The following antibiotic treatments were given: at 19 days of age, enrofloxacin; at 21 to 31 days of age, colistin plus amoxicillin; at 27 to 32 days of age, doxycycline; and at 27 to 34 days of age, tylosin. If the animal had diarrhea at the time of sampling, the cell within a table is shadowed. nt, this strain was not typeable by PFGE.

During the study, 30 of the 50 (60%) monitored calves developed diarrhea, but only in three animals was diarrhea accompanied by a slight increase in body temperature. Younger animals (14 to 18 days old) were diseased more commonly, accounting for 26 to 34% of calves per sampling point. The incidence dropped to 14 to 20% in older animals (≥25 days of age). Enteric disease (without elevated body temperature) was associated with C. difficile colonization in only 6 of all 21 (28.6%) animals that were C. difficile positive at any sampling point. All 6 of these animals were identified in the first two samplings, with 40% to 50% diarrheic animals per sampling point, while none of the colonized animals showed any signs of disease in further samplings (Table 2, data shown only for C. difficile-positive animals).

Distribution of C. difficile genotypes.

A total of 6 different PCR ribotypes (078, 126, 045, 033, 012, and 010) were identified among 38 isolated C. difficile strains (Tables 1 and 2). Of these, five PCR ribotypes were toxigenic and represented 95% of all isolates. Variant toxinotype V (PCR ribotypes 078, 126, and 045), comprising 30 (78.9%) isolates, predominated, whereas 3 (7.9%) isolates belonged to toxinotype XI (PCR ribotype 033) and 3 (7.9%) belonged to nonvariant toxinotype 0 (PCR ribotype 012). All isolates of toxinotypes V and XI were positive for cdtB, which encodes the binary toxin. Only 2 (5.3%) isolates were nontoxigenic C. difficile, and they were identified as PCR ribotype 010.

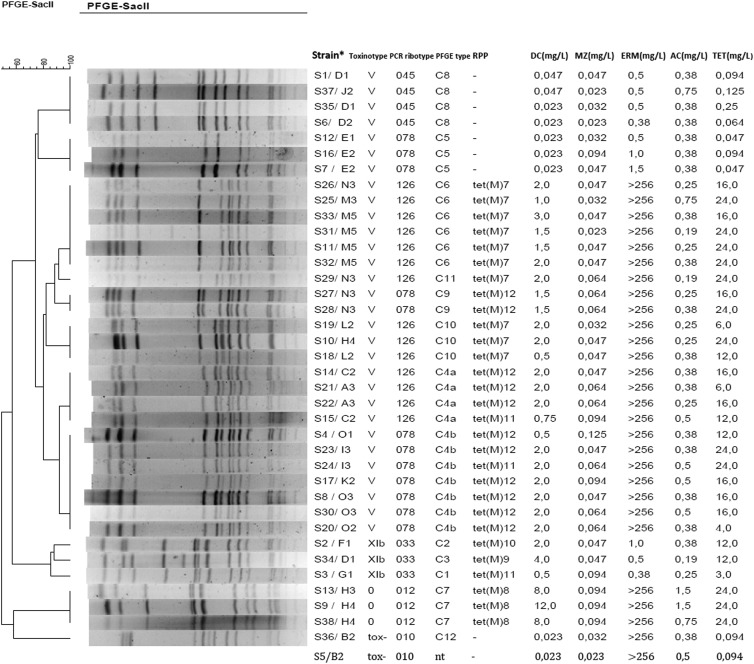

At the first two sampling points, diverse PCR ribotypes were detected, but later, PCR ribotypes 078 and 126 seemed to predominate (Tables 1 and 2). At sampling point 1, only 2 of 7 isolates belonged to PCR ribotype 078, while at sampling point 3, 11 of 12 isolates belonged to PCR ribotypes 078 and 126. PFGE analysis of 37 of 38 isolated strains (one strain, S5, was nontypeable) revealed 12 different PFGE types (C1 to C12). PFGE type C4 was subdivided into two subtypes (C4a and C4b) (Fig. 1). Three PFGE profiles could be differentiated within PCR ribotype 078, and four PFGE profiles were identified within PCR ribotype 126. Furthermore, up to three different PFGE profiles within PCR ribotype 078 or 126 could be differentiated within a single sampling point (Table 1). However, none of the PFGE types was present in all sampling points. Three PFGE profiles (C4b, C4a, and C5) were found only within the first three sampling points, whereas four profiles (C6, C7, C9, and C11) were detected only in the third and/or within the last three sampling points (Table 1).

Fig 1.

PFGE profiles of isolated strains, PCR ribotypes, tet(M) determinant types, and corresponding antibiotic resistances. nt, strain S5 was not typeable by PFGE, and therefore no profile is shown for this strain. Information for each strain is given as the strain designation/calf and sampling point (Strain*). DC, doxycycline; MZ, metronidazole; ERM, erythromycin; AC, amoxicillin; TET, tetracycline.

A single animal could be colonized with more than one PCR ribotype/PFGE type at the same time. For 11 randomly selected C. difficile-positive animals, we analyzed multiple colonies (up to 4 colonies) per plate, and in 3 of 11 (27.3%) tested samples, different genotypes (PCR ribotype/PFGE type) were found (Table 2, animals D, H, and N). One-third of all 15 positive animals were positive more than once, usually at two consecutive sampling points and with a persisting genotype (toxinotype/PCR ribotype/PFGE type) (Table 2).

Antibiotic resistance.

The MICs of erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, amoxicillin, and metronidazole were determined for all 38 obtained C. difficile isolates (Fig. 1). The tested antibiotics included two of the four antibiotics used for the treatment of the studied animals (Table 2). All strains were susceptible to amoxicillin and metronidazole. For three strains (animal G/S3, animal L/S19, and animal A/S21) (Table 2), MIC values determined by Etest indicated sensitivity to tetracycline, and this did not correlate with the presence of a tet determinant. As determined by Etest, 25 (65.8%) strains were resistant to tetracycline, with PCR ribotypes 078 and 126 accounting for 20 of 25 (80%) isolated strains; 28 (73.7%) were resistant to erythromycin, with ribotypes 078 and 126 representing 23 of 28 (82.1%) strains; and only 3 (7.9%) strains, all of which were PCR ribotype 012, were resistant to doxycycline. Coresistance to erythromycin and tetracycline was found in 23 (60.5%) of the isolates, mainly belonging to types 078 and 126. Only type 0/012 was resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin, and doxycycline concurrently (Table 2).

At the first and second sampling points, resistance to tetracycline was present in only 42.9% and 33.3% of the strains, respectively. However, 91.7% to 100.0% resistance was observed from the third sampling point onwards. A similar trend was observed for erythromycin resistance, which was found in 14.3% and 66.6% of strains from sampling points 1 and 2 and subsequently found in 100% of isolates from sampling point 3 onwards. Coresistance to tetracycline and erythromycin was found in 14.3% of isolates at sampling point 1 and rose to 100% coresistant strains at the last two C. difficile-positive sampling points (Table 2).

Antibiotic determinants.

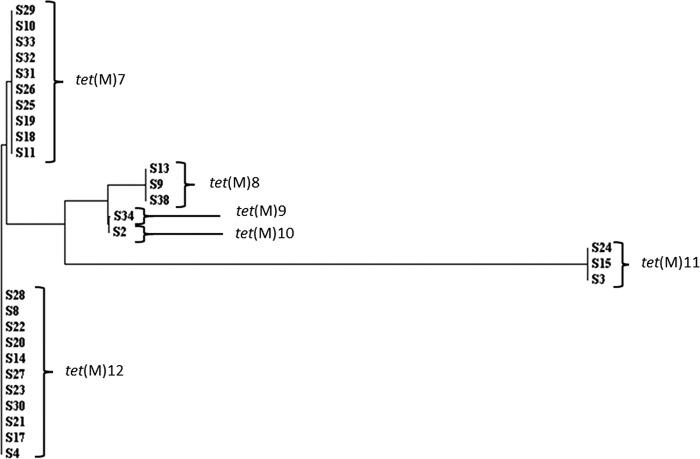

In order to determine if the same tetracycline resistance determinant was present in all strains, each isolate was subjected to PCR with degenerate primers designed to amplify a region of any of the known ribosomal protection protein genes conferring resistance to tetracycline. Twenty-nine of the strains were positive for tet(M), and all were sequenced in triplicate and compared to each other to detect differences within the genes. We found 6 sequence types among the tet(M) amplicons, which we labeled tet(M)7 (GenBank accession number JX500448), tet(M)8 (GenBank accession number JX500449), tet(M)9 (GenBank accession number JX500450), tet(M)10 (GenBank accession number JX500451), tet(M)11 (GenBank accession number JX500452), and tet(M)12 (GenBank accession number JX500453) (Fig. 1 and 2). Variants of tet(M) labeled tet(M)1 to tet(M)6 have previously been reported for C. difficile (40).

Fig 2.

Tree showing the relatedness of the tet(M) gene sequences to each other. Note that tet(M)9 and tet(M)10 are very similar and differ by only a single SNP.

By comparing the amplicons from different C. difficile strains isolated from a single animal at single or different time points, we showed that multiple genotypes of tet(M) were present (Table 2; Fig. 1). For instance, at time point 3, calf N contained two PCR ribotype 126 strains which carried tet(M)7 and two PCR ribotype 078 strains which carried tet(M)12. Another example is calf H, which at time point 4 contained an isolate of PCR ribotype 126 (strain S10) with a tet(M)7 genotype and also contained two other isolates at the same time point. These were both PCR ribotype 012 strains, and both contained tet(M)8; a strain with identical properties had already been found in animal H at a previous sampling point. Calf C is an example of an animal carrying two similar strains (same PCR ribotype and same PFGE type) that differed in tet determinants.

When the tet(M) genotypes were considered at each time point and between time points, it was apparent that the profile present in the sampled group of animals changed over time. During the first sampling time, four different tet(M) genotypes were seen [tet(M)9, tet(M)10, tet(M)11, and tet(M)12]. Genotypes tet(M)9 and tet(M)10 were observed only at the first sampling point, while tet(M)11 and tet(M)12 could also be detected at the second and third sampling points, in different strains and/or animals (Table 2).

The final tet(M) group, tet(M)7, is interesting because it did not appear before time point 2. All isolates containing tet(M)7 belonged to PCR ribotype 126 (Table 2; Fig. 1). The closest group to tet(M)7 is tet(M)12 (Fig. 2). However, 8 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were detected in a sequence of 1,002 bp, so it is unlikely that one of the genotypes arose from the other due to mutation (Fig. 2).

Sporulation properties.

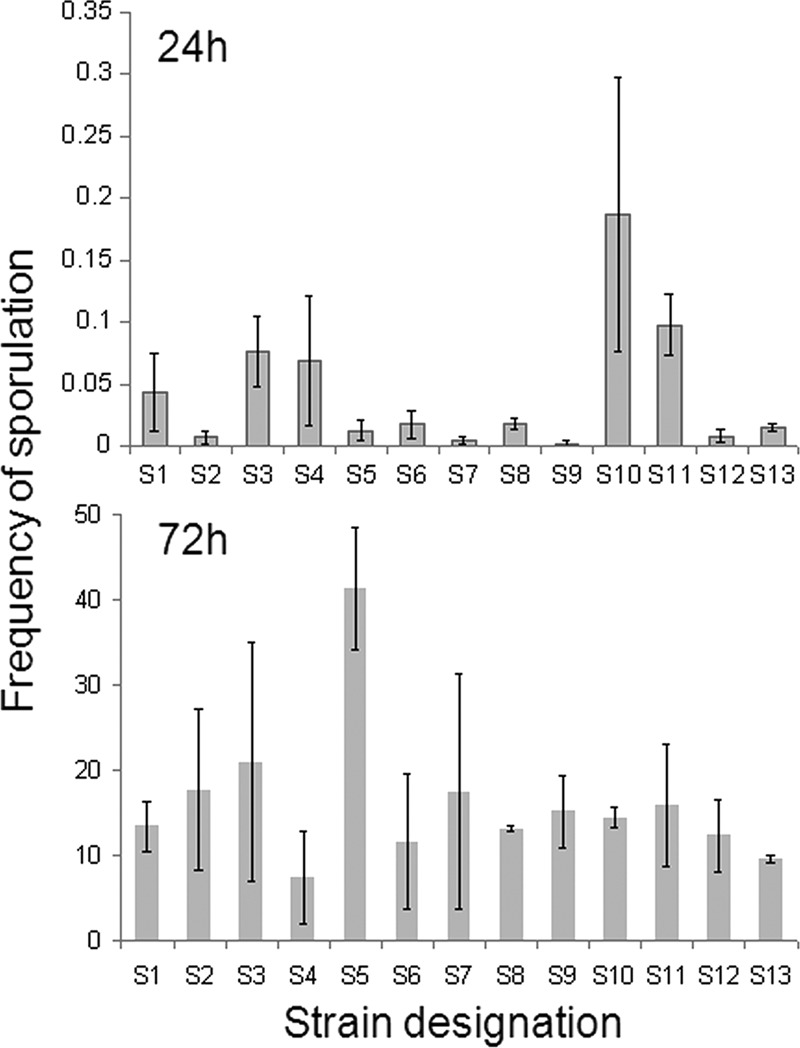

The frequency of sporulation, defined by the percentage of heat-resistant spore counts among total viable cells (including free spores and sporulating and nonsporulating cells), was estimated 24 and 72 h after inoculation under laboratory conditions. In earlier work, we noticed that strains may differ significantly in terms of their frequency of sporulation measured early (24 h) after inoculation but that these differences may even out with time (our unpublished results). These two time points were thus chosen because they enabled detection of early differences in frequencies of sporulation, which may be advantageous in a natural setting, as well as maximum sporulation frequencies. As shown in Fig. 3, the sporulation frequency 72 h following inoculation was approximately 15%, and with the single exception of strain S5, it did not vary by more than 10% among all other strains. Strain S5 of PCR ribotype 010 clearly differed, exhibiting a 40% frequency of sporulation.

Fig 3.

Sporulation frequencies (%) of some representative strains after 24 and 72 h of incubation in BHI medium.

In contrast, three different groups were apparent 24 h after inoculation. Strains S10 and S11, both belonging to PCR ribotype 126, showed sporulation frequencies equal to or slightly larger than 0.1% (0.1 and 0.2%, respectively), whereas for isolates S1, S3, and S4, representing three different PCR ribotypes, the sporulation frequencies ranged from 0.05 to 0.1%. All other strains (S2, S5 to S9, S12, and S13) showed frequencies of sporulation below 0.01% at this time point. Clearly, the strains with the highest final frequencies of sporulation may not show the highest values at an early time point (as for S5). Conversely, the best early spore formers may not be among the strains with the highest final frequencies of spore formation (as in the case of strain S4).

DISCUSSION

This study is one of the few longitudinal studies on veal calf farms and the first one that also includes characterization of antibiotic resistance determinants and sporulation properties of C. difficile strains. C. difficile colonization rates in this study decreased with calf age and did not correlate with the presence of symptoms. This is in agreement with previous studies describing the lack of an association between a positive toxin assay, positive C. difficile culture, and diarrhea in calves (17, 32).

From currently available data, it seems that different animal species are associated with different C. difficile PCR ribotypes (25, 26, 44). PCR ribotypes found in cattle so far include ribotypes 078, 002, 012, 017, 077, 027, 014, and 033 (1, 12, 25, 26, 32). While our data are in agreement with these previous findings, the present study is unique in that it sampled the same 50 individual animals over a long period. This enabled us to study the onset and duration of colonization, as well as possible changes of genotypes within individual animals over time. Upon arrival, the diversity of PCR ribotypes was high, but at the next sampling point, after less than a week, PCR ribotypes 078 and 126 started to predominate. In the first month, type 078 was isolated more often, but it was later replaced by type 126. PCR ribotypes 078 and 126 are very similar to each other in their PCR ribotyping profiles and are sometimes reported as 078/126 or not even differentiated. The large diversity in PCR ribotypes at calf arrival was to be expected, since the calves originated from a large number of different herds of birth. Another longitudinal study of C. difficile on a veal farm in Canada reported similar observations regarding the increase of colonization after the first week on the farm and a decrease in PCR ribotype diversity (11). Also, in that study, PCR ribotype 078 was the most prevalent, but 11 other PCR ribotypes were found. These additional PCR ribotypes were not designated by the international Cardiff nomenclature and therefore could not be compared to our data. In another study, isolation rates were much lower, and only one PCR ribotype (078) was found (12).

Since in our study types 078 and 126 were present in several animals for almost the entire study period, the obvious question was whether this was the consequence of clonal spread between animals within the farm. Also, given the frequent oral antimicrobial treatments in the milk during the first months after arrival, it can be questioned whether some fitness-related properties, such as antibiotic resistance and sporulation dynamics (given that spores are resilient, persistent, and not susceptible to antibiotics), are associated with the persistence of types 078 and 126.

Several studies have used PFGE or multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) to discriminate strains within a given PCR ribotype. PCR ribotypes 078 and 126 are difficult to study with MLVA because two of the loci are not amplified in these types, and hence the discriminatory power is reduced (27). The apparent clonality of PCR ribotype 078 reported by other studies using MLVA is probably due to low discriminatory power (26). Improved MLVA methodology, as well as improved PFGE methods, has shown that PCR ribotype 078 can also be heterogeneous (3, 23). Here we showed that none of the PCR ribotype 078 and 126 strains isolated from the same veal farm at the same time point were clonal and that these strains could be distinguished by PFGE, sporulation properties, and genes for tetracycline resistance.

It was shown before for other C. difficile PCR ribotypes (particularly for type 027) that sporulation properties are not associated with the PCR ribotype (9). The same observation was made here. Also, an increased sporulation frequency could not be associated with the prolonged presence of a specific PCR ribotype/PFGE type in the studied animals. The PCR ribotype 010 strain S5, which showed the highest sporulation frequency after 72 h, was isolated only once. Another type (078/C4b) was found in three calves at sampling points 1 and 3, and two strains belonging to this type (S4 and S8) did not show increased sporulation. However, two other types, present in more than one animal and in more than a single sampling (strain S11 [PCR ribotype 126/C6] and strain S10 [PCR ribotype 126/C10]), did show the highest frequencies of sporulation at 24 h.

We sequenced the amplicons from the tet(M) gene present in each strain at each time point and from each animal to ascertain whether the resistance was due to clonal spread of resistance genes among C. difficile strains or to spread of a clonal population of C. difficile in the cattle population. A high level of tetracycline resistance in calves was described before (11), and tet(M), tet(O), and tet(W) were detected. We found only tet(M) genes that could be distributed into 6 subtypes. Specific tet(M) sequence types were usually found in single or related PCR ribotypes/PFGE types. Only tet(M)11 was found in three different PCR ribotypes (033, 078, and 126) and at three sampling points, which may indicate that the tet(M) gene moved between strains within the farm. The tet(M) gene is usually found on conjugative transposons of the Tn916-like family (31), which are widespread in C. difficile (7, 8, 10, 40), so it is likely that any movement was facilitated by these elements.

At present, antimicrobials in veal calves are still widely used (30). By comparing the antibiotic treatments of animals included in this study and antibiotic resistances present in the C. difficile isolates (Table 2), it seems that at least some of the antibiotics did not select for resistant strains, e.g., amoxicillin, while other resistances were present before the use of antibiotics. Resistance genes are often linked on the same mobile genetic element, e.g., those for tetracycline and erythromycin resistance and those for erythromycin and tylosin resistance are often linked. Therefore, the selection of one will inadvertently select for the other.

In summary, we have shown that calves were already colonized with different C. difficile PCR ribotypes on arrival at the veal farm and that as the production cycle progressed, PCR ribotypes 078 and 126 started to predominate. This was not a result of clonal spread of a particular 078 or 126 strain in the farm, as strains within the PCR ribotype could be differentiated by their PFGE profiles and tet genes. It seems that these two PCR ribotypes are best adapted to the animal host and can therefore colonize calves longer than strains of other PCR ribotypes can. Strains isolated at later time points were more likely to be resistant to tetracycline and erythromycin and had higher sporulation frequencies at 24 h, suggesting that these two properties contribute to the persistence of C. difficile within this particular environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement 223585 and by FCT-MCTES, through grants ERA-PTG/SAU/0002/2008 (to A.O.H.) and PEst-OE/EQB/LA0004/2011. A.P.R. was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (grant G0601176).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Avbersek J, et al. 2009. Diversity of Clostridium difficile in pigs and other animals in Slovenia. Anaerobe 15:252–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baker AA, Davis E, Rehberger T, Rosener D. 2010. Prevalence and diversity of toxigenic Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium difficile among swine herds in the Midwest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2961–2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakker D, et al. 2010. Relatedness of human and animal Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 078 isolates determined on the basis of multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis and tetracycline resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:3744–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barbut F, et al. 2007. European study group on Clostridium difficile (ESGCD prospective study of Clostridium difficile infections in Europe with phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of the isolates). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:1048–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bauer MP, Notermans, et al. 2011. Clostridium difficile infection in Europe: a hospital-based survey. Lancet 377:63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bidet P, Barbut F, Lalande V, Burghoffer B, Petit JC. 1999. Development of a new PCR-ribotyping method for Clostridium difficile based on ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brouwer MS, Warburton PJ, Roberts AP, Mullany P, Allan E. 2011. Genetic organisation, mobility and predicted functions of genes on integrated, mobile genetic elements in sequenced strains of Clostridium difficile. PLoS One 6:e23014 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brouwer MS, Roberts AP, Mullany P, Allan E. 2012. In silico analysis of sequenced strains of Clostridium difficile reveals a related set of conjugative transposons carrying a variety of accessory genes. Mob. Genet. Elements 2:8–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burns DA, Heap JT, Minton NP. 2010. The diverse sporulation characteristics of Clostridium difficile clinical isolates are not associated with type. Anaerobe 16:618–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a. CLSI 2011. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 21st informational supplement. M100-S21, vol 31, no 1 CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corver J, et al. 2012. Analysis of a Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 078 100 kilobase island reveals the presence of a novel transposon, Tn6164. BMC Microbiol. 12:130 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Costa MC, Stämpfli HR, Arroyo LG, Pearl DL, Weese JS. 2011. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile on a veal farm: prevalence, molecular characterization and tetracycline resistance. Vet. Microbiol. 152:379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Costa MC, et al. 2012. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile isolated from feedlot beef cattle upon arrival and mid-feeding period. BMC Vet. Res. 8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fawley WN, Wilcox MH. 2002. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis can yield DNA fingerprints of degradation-susceptible Clostridium difficile strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3546–3547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goorhuis A, et al. 2008. Emergence of Clostridium difficile infection due to a new hypervirulent strain, polymerase chain reaction ribotype 078. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:1162–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goorhuis A, et al. 2008. Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 078: an emerging strain in humans and in pigs? J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1157–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gould LH, Limbago B. 2010. Clostridium difficile in food and domestic animals: a new foodborne pathogen? Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:577–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hammitt MC, et al. 2008. A possible role for Clostridium difficile in the etiology of calf enteritis. Vet. Microbiol. 127:343–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harvey RB, et al. 2011. Clostridium difficile in poultry and poultry meat. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8:1321–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henriques AO, Moran CP. 2000. Structure and assembly of the bacterial endospore coat. Methods 20:95–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hopman NE, et al. 2011. Acquisition of Clostridium difficile by piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 149:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jamal WY, et al. 2009. Correlation of multidrug resistance, toxinotypes and PCR ribotypes in Clostridium difficile isolates from Kuwait. J. Chemother. 21:521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Janezic S, Rupnik M. 2010. Molecular typing methods for Clostridium difficile: pulsed-field electrophoresis and PCR ribotyping. Methods Mol. Biol. 646:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Janezic S, Ocepek M, Zidaric V, Rupnik M. 2012. Clostridium difficile genotypes other than ribotype 078 that are prevalent among human, animal and environment isolates. BMC Microbiol. 12:48 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jhung MA, et al. 2008. Toxinotype V Clostridium difficile in humans and food animals. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1039–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keel K, Brazier JS, Post KW, Weese S, Songer JG. 2007. Prevalence of PCR ribotypes among Clostridium difficile isolates from pigs, calves, and other species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1963–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koene MG, et al. 2012. Clostridium difficile in Dutch animals: their presence, characteristics and similarities with human isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:778–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marsh JW, et al. 2011. Multi-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis for investigation of the genetic association of Clostridium difficile isolates from food, food animals and humans. Anaerobe 17:156–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Medina-Torres CE, Weese JS, Staempfli HR. 2011. Prevalence of Clostridium difficile in horses. Vet. Microbiol. 152:212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Norman KN, et al. 2009. Varied prevalence of Clostridium difficile in an integrated swine operation. Anaerobe 15:256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pardon B, et al. 2012. Prospective study on quantitative and qualitative antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory drug use in white veal calves. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1027–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roberts AP, Mullany P. 2011. Tn916-like genetic elements: a diverse group of modular mobile elements conferring antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:856–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodriguez-Palacios A, et al. 2006. Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes in calves, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1730–1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodriguez-Palacios A, Pickworth C, Loerch S, LeJeune JT. 2011. Transient fecal shedding and limited animal-to-animal transmission of Clostridium difficile by naturally infected finishing feedlot cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3391–3397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodriguez-Palacios A, Koohmaraie M, LeJeune JT. 2011. Prevalence, enumeration, and antimicrobial agent resistance of Clostridium difficile in cattle at harvest in the United States. J. Food Prot. 74:1618–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rupnik M, Avesani V, Janc M, Von Eichel-Streiber C, Delmée M. 1998. A novel toxinotyping scheme and correlation of toxinotypes with serogroups of Clostridium difficile isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2240–2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rupnik M, Widmer A, Zimmermann O, Eckert C, Barbut F. 2008. Clostridium difficile toxinotype V, ribotype 078, in animals and humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Songer JG, Anderson MA. 2006. Clostridium difficile: an important pathogen of food animals. Anaerobe 12:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Songer JG, et al. 2009. Clostridium difficile in retail meat products, USA, 2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:819–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL. 2008. Bile salts and glycine as cogerminants for Clostridium difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 190:2505–2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spigaglia P, Barbanti F, Mastrantonio P. 2006. New variants of the tet(M) gene in Clostridium difficile clinical isolates harbouring Tn916-like elements. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:1205–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stubbs S, et al. 2000. Production of actin-specific ADP-ribosyltransferase (binary toxin) by strains of Clostridium difficile. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186:307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Warburton P, et al. 2009. Characterization of tet(32) genes from the oral metagenome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:273–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weese JS, Reid-Smith RJ, Avery BP, Rousseau J. 2010. Detection and characterization of Clostridium difficile in retail chicken. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 50:362–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weese JS, Wakeford T, Reid-Smith R, Rousseau J, Friendship R. 2010. Longitudinal investigation of Clostridium difficile shedding in piglets. Anaerobe 16:501–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weese JS. 2010. Clostridium difficile in food—innocent bystander or serious threat? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilson KH, Kennedy MJ, Fekety FR. 1982. Use of sodium taurocholate to enhance spore recovery on a medium selective for Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:443–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zidaric V, Zemljic M, Janezic S, Kocuvan A, Rupnik M. 2008. High diversity of Clostridium difficile genotypes isolated from a single poultry farm producing replacement laying hens. Anaerobe 14:325–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]