Abstract

Changes in polymerized actin during stress conditions were correlated with potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber protein synthesis. Fluorescence microscopy and immunoblot analyses indicated that filamentous actin was nearly undetectable in mature, quiescent aerobic tubers. Mechanical wounding of postharvest tubers resulted in a localized increase of polymerized actin, and microfilament bundles were visible in cells of the wounded periderm within 12 h after wounding. During this same period translational activity increased 8-fold. By contrast, low-oxygen stress caused rapid reduction of polymerized actin coincident with acute inhibition of protein synthesis. Treatment of aerobic tubers with cytochalasin D, an agent that disrupts actin filaments, reduced wound-induced protein synthesis in vivo. This effect was not observed when colchicine, an agent that depolymerizes microtubules, was used. Neither of these drugs had a significant effect in vitro on run-off translation of isolated polysomes. However, cytochalasin D did reduce translational competence in vitro of a crude cellular fraction containing both polysomes and cytoskeletal elements. These results demonstrate the dependence of wound-induced protein synthesis on the integrity of microfilaments and suggest that the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton may affect translational activity during stress conditions.

Protein synthesis of mature potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers varies in response to the abiotic stresses of mechanical wounding and hypoxia. Translational activity of postharvest tubers is low (Morelli et al., 1994), in accord with the slow respiration of this dormant organ after detachment from the mother plant. Mechanical wounding of postharvest tubers initiates a rapid increase in protein synthesis and expression of wound-response genes but only in an area limited to within 1 cm of the wound site (Butler et al., 1990; Morelli et al., 1994). The tuber wound response is biphasic, with a 4- to 5-fold increase in protein synthesis in the first 2 h after wounding, and a secondary induction apparent between 12 and 24 h that elevates synthetic activity 10- to 20-fold over initial levels (Morelli et al., 1994; Vayda and Morelli, 1994). These periods of high translational activity correlate with expression of two sets of wound-response genes: (a) those involved with formation of a physical barrier to infection and (b) those involved in cell division (for review, see Davis et al., 1990; Vayda and Morelli, 1994). In contrast, the initial response of tubers to a low-oxygen environment is acute inhibition of protein synthesis. Wounded aerobic tubers cease incorporation of [35S]Met within 30 min of transfer to a hypoxic environment (Vayda and Schaeffer, 1988). Translation resumes at a depressed rate after several hours of hypoxic incubation, with synthesis of alcohol dehydrogenase, Fru-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, and other proteins (Vayda and Schaeffer, 1988; Butler et al., 1990). However, it is not known what mechanisms mediate activation of tuber protein synthesis from the quiescent state, inhibition of protein synthesis at the onset of low-oxygen stress, or reactivation of protein synthesis during prolonged hypoxia.

Stimulation of protein synthesis upon wounding involves a rapid reorganization of polysomes and mobilization of existing ribosomes. mRNAs, which are stably associated with polysomes in mature tubers for up to 9 months postharvest, are displaced from polysomes and degraded completely within 60 min after wounding (Butler et al., 1990; Davis et al., 1990; Crosby and Vayda, 1991; Bhatt and Knowler, 1992). During this same period, wound-response mRNAs accumulate, associate with polysomes, and are translated (Butler et al., 1990; Crosby and Vayda, 1991). Wound-induced translational activity corresponds with increased polysome abundance both in pea and in potato (Davies and Schuster, 1981; Schuster and Davies, 1983; Davies et al., 1986; Crosby and Vayda, 1991), with new polysomes apparently assembled from the existing ribosome pool (Schuster and Davies, 1983). In contrast, acute inhibition of protein synthesis during low-oxygen stress causes a significant reduction in polysome abundance, with a corresponding increase in abundance of monomeric ribosomes and ribosomal subunits (Lin and Key, 1967; Bailey-Serres and Freeling, 1990; Fennoy and Bailey-Serres, 1995). These observations suggest that reinitiation of translation is impaired. However, low-oxygen stress appears to block translation elongation reactions as well. Although aerobically expressed mRNAs remain bound to polysomes (Crosby and Vayda, 1991), they are not translated in vivo (Butler et al., 1990). Furthermore, polysomes isolated from low-oxygen-stressed tissues perform very poorly in translational run-off reactions in vitro (Crosby and Vayda, 1991; Webster et al., 1991b).

Elevated translational activity in tissues is correlated with several factors, including phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (Scharf and Nover, 1982; Bailey-Serres and Freeling, 1990; Jefferies and Thomas, 1996), association of the acidic ribosomal protein P40 with polysomes (Garcia-Hernandez et al., 1996), and steady-state abundance of eEF1A (Pokalsky et al., 1989; Ursin et al., 1991; Morelli et al., 1994; Habben et al., 1995). However, none of these factors satisfactorily explains translational arrest during low-oxygen stress. Phosphorylation of S6 does not occur during low-oxygen stress (Bailey-Serres and Freeling, 1990; Crosby and Vayda, 1991) but neither does dephosphorylation; S6 pulse labeled with 32PO4 under aerobic conditions retained this label when potato tubers were transferred to low oxygen (Crosby and Vayda, 1991). The latter result indicates that dephosphorylation of S6 is unlikely to be responsible for translational arrest. Furthermore, steady-state abundance of eEF1A remains high when wounded tubers are transferred to low-oxygen conditions (Vayda et al., 1995). Thus, it is not clear what mechanisms regulate protein synthesis during stress conditions.

One intriguing possibility proposed by Davies (1993) is that protein synthesis might be affected by environmental cues that induce changes in the cytoskeleton. Many components of the translational machinery are localized to the cytoskeleton, fractionate with cytoskeletal preparations, or are made soluble by treatments that depolymerize cytoskeletal elements (Hesketh and Pryme, 1991; Durso and Cyr, 1994a; Hesketh, 1994; Condeelis, 1995; Bassell and Singer, 1997). These include mRNA and polysomes of both animals (Toh et al., 1980; Ornelles et al., 1986; Hesketh and Pryme, 1988; Hesketh et al., 1991; Taneja et al., 1992; Bassell, 1993; Bassell et al., 1994) and plants (Davies et al., 1991, 1993; Ito et al., 1994). The cytoskeletal framework of detergent-treated, membrane-free cells contains polysomes that support protein synthesis in vitro (Biegel and Pachter, 1991), as does the low-speed cytoskeletal fraction described by Ito et al. (1994). Cytochalasin D has been shown to reversibly inhibit protein synthesis in intact HeLa cells but not in rabbit reticulocyte or HeLa cell lysates in vitro (Ornelles et al., 1986). Thus, it is possible that polymerization or depolymerization of the cytoskeleton could affect protein synthesis in vivo. For these reasons, we investigated whether mechanical wounding or subsequent low-oxygen stress altered the polymerization state of actin in a manner that might contribute to the observed changes in translational activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mature potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv Russet Burbank) tubers were obtained from the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station (Presque Isle, ME) or purchased in a local market. After harvest tubers were stored for 2 weeks at room temperature and then at 4°C prior to use. Actively growing tubers were harvested from greenhouse-grown plants at the University of Maine (Orono). All tubers were rinsed briefly with warm water, surface sterilized by brief immersion in 5% (v/v) bleach, then dried and allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for 16 to 24 h before use. Tubers were wounded by insertion of a P-200 micropipette tip to a depth of 1.5 cm as described previously (Vayda and Schaeffer, 1988). Hypoxic conditions were established by incubating tubers in a moist argon atmosphere (< 2% oxygen), as described previously (Vayda and Schaeffer, 1988; Butler et al., 1990).

Cell Fractionation

Three-gram samples of tissue were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in 10 mL of CSB, consisting of 5 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 10 mm Mg(OAc)2, 2 mm EGTA, 2 mm PMSF, 15 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5% polyoxyethylene-10-tridecyl ether, as described by Abe and Davies (1991, 1995). All solutions and operations were maintained at 4°C. The homogenate was filtered through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem) and centrifuged at 250g for 7 min. The supernatant was removed and centrifuged for 15 min at 4,000g. After the supernatant was carefully decanted, the pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of CSB. In some cases, the supernatant was further fractionated by centrifugation at 15,000g for 15 min. Polysomes were isolated from 2-h-wounded tubers by extraction in polysome buffer (Crosby and Vayda, 1991; Vayda, 1995) containing 400 mm KCl and sedimentation through a 1.5 m Suc cushion, as described by Vayda (1995). Protein concentrations of cell fractions were determined by the Bradford (1976) assay using BSA as the standard.

Analysis of Cell Fractions

Proteins associated with cell fractions were resolved by electrophoresis through 15% SDS-PAGE gels as described previously (Morelli et al., 1994). Twenty micrograms of protein was loaded per lane and either stained with Coomassie blue R-250 or electroblotted to Hybond C membranes (Amersham), as described by Morelli and Vayda (1996). Actin and β-tubulin were detected using 1:5000 dilutions of commercial monoclonal antibodies (Amersham). Bound antibody was visualized using peroxidase-conjugated second antibodies (Pierce) and the enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (Amersham). Exposure time to Kodak X/AR 5 film ranged from 20 s to 10 min.

Dissociation and Reconstitution of Actin

The effect of KCl concentration on sedimentation of actin was tested by resuspension of the 4,000g pellet in 100 μL of CSB, division of the sample to equal aliquots, and dilution of aliquots to 1 mL with CSB containing 80, 130, or 200 mm KCl prior to centrifugation to obtain the 4,000g pellet and supernatant fractions. Alternatively, actin was solubilized by resuspension of the pellet in 1 mL of 5 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, containing 100 mm KCl, 400 mm KI, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm PMSF, 0.1 mm sodium vanadate, and 1 μg mL−1 leupeptin (Cox and Muday, 1994). After gentle rocking for 20 min at 4°C, the solution was clarified by centrifugation at 40,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 2 L of 5 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, containing 100 mm KCl, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm PMSF, 250 mm Suc, 0.1 mm sodium vanadate, and 5 mm benzamidine. Material pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000g for 5 min was resuspended in 300 μL of 5 mm Hepes, pH 7.0, containing 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm PMSF, 250 mm Suc, 0.1 mm sodium vanadate, and 5 mm benzamidine.

Assessment of Protein Synthesis

Tubers were labeled in vivo by incubation of 0.25 mCi of [35S]Met (Amersham) in a tuber wound, as described previously (Morelli et al., 1994). After a 30-min incubation at 20°C, the 2 g of tuber tissue immediately surrounding the wound site was ground in 2 mL of 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 15 mm β-mercaptoethanol. Translational activity was measured as TCA-precipitable counts in 10 μL of clarified extract and then extrapolated to total sample volume. A translational run-off assay using 10 μg of isolated polysomes was performed as described by Vayda (1995). The ability of the 4000g pellet to support protein synthesis was also evaluated using the run-off translation assay (Vayda, 1995); after resuspending the 4000g pellet in 50 μL of translation cocktail, 20 μg was used as the template for run-off translation in place of 10 μg of isolated polysomes. All translational run-off assays contained 100 μm m7GMP and 100 μm chloramphenicol.

Fluorescent Detection of F-Actin

Thin sections of nonwounded, wounded, or hypoxic tubers were cut by a microtome and fixed immediately for 10 min in 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde prepared in CSB, as described by Panteris et al. (1992). The 60- to 120-μm thick sections were stained using 330 nm rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and mounted onto slides as described by Abe and Davies (1991, 1995). Slides were examined with a DMRXE upright light microscope (Leica) using ×2.5 to ×40 Fluotar objectives. Images were captured using a DEI-470 charge-coupled device video camera system (Optronics Engineering, Goleta, CA) attached to a Leica Quantmet 600HR image analysis workstation. Fluorescent images were illuminated through a Leica rhodamine filter (single-pass excitation, 520–545 nm; barrier, 635 nm).

Drug Treatments

Stock solutions of 5 mg mL−1 cytochalasin D, 1 mm colchicine, and 10 mm cycloheximide (all from Sigma) were prepared in 50% (v/v) DMSO. Upon dilution to working conditions, the final DMSO concentration was adjusted to 1% with distilled water. Tubers were wounded by insertion of sterile P-200 pipette tips. Tips were removed and tubers were immediately incubated with 50 μL of 1% DMSO in water (mock), 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D, 10 μm colchicine, or inhibitors at the concentrations indicated in the figures. Tubers were incubated at 20°C for 2 h prior to sample isolation or labeling with 0.25 mCi [35S]Met or [3H]uridine (Amersham). Tissue within 3 mm of each wound site was removed with a razor blade and pooled to obtain each 2-g sample. For translational run-off experiments, 1 μL of the diluted stock solutions was added directly to the reaction mixture to provide a final concentration of 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D, 10 μm colchicine, or 50 μm cycloheximide.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Presence of Rapidly Sedimenting Actin in Wounded Tuber Extracts

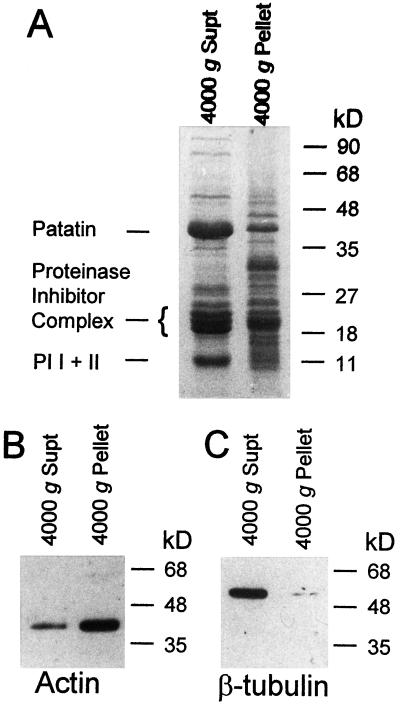

Davies and collaborators demonstrated that F-actin sediments under low-g forces (4000g) in a low-ionic-strength buffer (Abe and Davies, 1991; Abe et al., 1991, 1992; Ito et al., 1994; Abe and Davies, 1995). Centrifugation of clarified potato tuber extracts at 4000g for 15 min typically yielded 150 to 200 μg of protein in the pellet. The most prominent polypeptides present in the supernatant fraction were the 42-kD patatin, the 22- to 25-kD proteinase inhibitor complex, and the 11-kD proteinase inhibitors I and II (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the 4000g pellet contained a more diverse set of polypeptides (Fig. 1A). Actin polypeptide was detected by immunoblot in both the pellet and supernatant fractions of 2-h-wounded tubers (Fig. 1B). When the volume of the fractions is taken into account it is apparent that greater than 90% of total cellular actin remained in the supernatant fraction. However, the relative abundance of actin per microgram of protein was greater in the pellet fraction than in the supernatant. By contrast, only trace amounts of β-tubulin were observed in the pellet fraction (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of the 4000g pellet and supernatant (Supt) fractions from 2-h-wounded aerobic tuber extract. A, Polypeptides present in 20 μg of each fraction were resolved in a 15% gel stained with Coomassie blue R-250. Mobility of molecular size standards (Bio-Rad) and identification of major species are shown. Immunoblots of duplicate lanes on the same gel were electroblotted to a Hybond C nylon membrane and probed with either anti-actin monoclonal antibody (B) or anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (C).

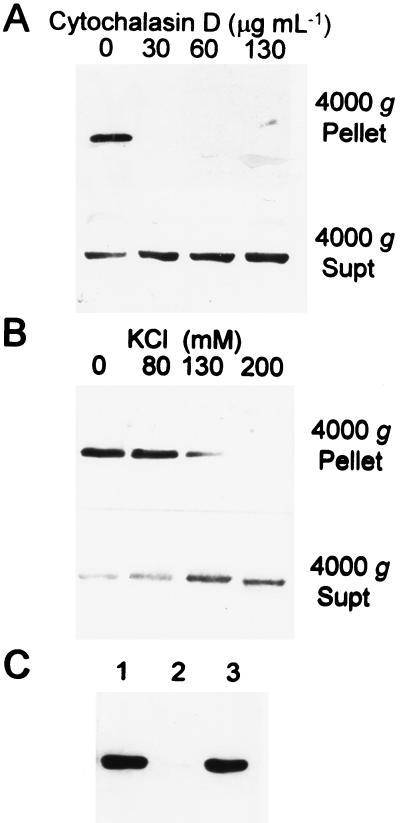

Subsequent centrifugation of the supernatant fraction at 15,000g for 15 min pelleted only trace amounts of actin and β-tubulin (data not shown). These results suggested that only a small fraction of the actin present in postharvest tuber cells is polymerized into microfilaments. Sedimentation of actin in the 4000g pellet was deemed significant because treatments known to destabilize microfilaments displaced actin to the supernatant fraction. Actin was not detected in the pellet fraction of 2-h-wounded tubers treated with 32 μg mL−1 or greater cytochalasin D (Fig. 2A). Incubation of tubers with 20 μm colchicine had no effect on actin recovery in the 4000g pellet, whereas 5 μm colchicine was sufficient to displace the trace amounts of β-tubulin present in the 4000g pellet of 2-h-wounded tubers to the 4000g supernatant (data not shown). Incubation of the resuspended 4000g pellet in CSB containing 130 mm KCl reduced the amount of actin recovered in the 4000g pellet upon subsequent centrifugation, and actin failed to sediment with the 4000g pellet in CSB containing 200 mm KCl (Fig. 2B). Actin in the 4000g pellet could be solubilized by resuspension in buffer containing 400 mm KI (Cox and Muday, 1994) and subsequently recovered upon removal of KI by dialysis (Fig. 2C). Both the initial 4000g pellet and actin recovered after dialysis exhibited fluorescence in the presence of 330 nm rhodamine-phalloidin. From these results we concluded that the 4000g pellet contained polymerized actin, albeit a small fraction of the total actin present in postharvest tubers.

Figure 2.

Recovery of actin in the 4,000g pellet and supernatant (Supt) fractions of 2-h-wounded tuber extracts prepared in the presence of agents that depolymerize actin filaments. A, Anti-actin immunoblot of extracts prepared from sections of a tuber treated for 30 min with 1% DMSO (mock) or 32, 65, or 130 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D. B, Anti-actin immunoblot of aliquots from a single 2-h-wounded tuber extract adjusted to 80, 120, or 200 mm KCl. C, Anti-actin immunoblot of polypeptides present in the 4,000g pellet fraction prior to addition of 400 mm KI (lane 1), in the 4,000g pellet in the presence of 400 mm KI (lane 2), and in the 12,000g pellet after dialysis to remove KI (lane 3). Twenty micrograms of protein was loaded per lane in A and B; 10-μL aliquots of pellets resuspended in equivalent volumes (100 μL) was loaded per lane in C.

Abundance of F-Actin Changes in Response to Wounding and Hypoxia

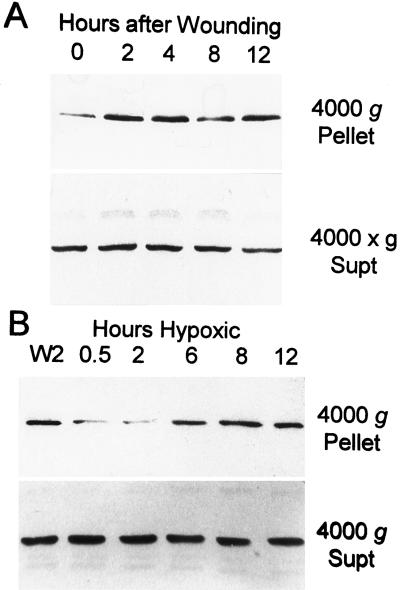

Abundance of actin in the 4000g pellet was very low for most nonwounded tubers tested (Fig. 3A) and was undetectable for others (data not shown). However, the amount of rapidly sedimenting actin increased within 2 to 4 h after wounding and further increased between 8 and 12 h after wounding (Fig. 3A). These increases corresponded to periods of wound-induced translational activity measured by [35S]Met incorporation in vivo (Table I). In contrast, transfer of 2-h-wounded tubers to an argon atmosphere reduced the amount of actin recovered in the 4000g pellet fraction (Fig. 3B). Sedimentable actin was lowest during the initial 2 h of low-oxygen stress (Fig. 3B), when protein synthesis was maximally depressed (Table I). In contrast, actin was more prevalent in the 4000g pellet of tubers maintained under argon for 6 h or longer (Fig. 3B), which exhibited renewed translational activity (Table I). These results suggest at least a casual relationship between translational activity and the polymerization state of actin filaments.

Figure 3.

Detection of actin in the 4000g pellet fraction of wounded and low-oxygen-stressed tubers. A, The 4000g pellet and supernatant (Supt) fractions were obtained from a tuber prior to wounding (lane 0) and sections of that same tuber 2, 4, 8, or 12 h after wounding. B, The 4000g pellet and supernatant fractions were prepared from sections of a tuber 2 h after wounding, and that same tuber was subsequently incubated under argon for 0.5, 2, 6, 8 or 12 h. The anti-actin immunoblot gels contained 20 μg of protein per lane.

Table I.

Incorporation in vivo of [35S]Met by wounded and low-oxygen-stressed potato tubers

| Treatment | Incorporationa |

|---|---|

| h after stress induction | |

| Wounded aerobic tubersb | |

| 0 | 0.51 ± 0.11 |

| 2 | 2.48 ± 0.25 |

| 4 | 2.63 ± 0.43 |

| 8 | 2.04 ± 0.33 |

| 12 | 4.88 ± 0.86 |

| 2-h-Wounded and low-oxygen stressed tubersc | |

| 0 | 2.57 ± 0.32 |

| 0.5 | 0.38 ± 0.16 |

| 2 | 0.22 ± 0.09 |

| 6 | 0.61 ± 0.13 |

| 8 | 0.72 ± 0.11 |

| 12 | 1.10 ± 0.09 |

Incorporation was measured as TCA-precipitable counts per minute (× 106) per gram fresh weight in extracts of soluble protein prepared after a 15-min labeling at 20°C as described previously (Vayda and Schaeffer, 1988). TCA precipitation assays were performed in triplicate. Activity is the mean ± se for three independent trials.

[35S]Met (0.25 mCi) was presented to tuber wounds at the time of wounding (0 h) or at the times indicated after wounding.

Low-oxygen stress was imposed on tubers 2 h after wounding, and label was presented at the times indicated after transfer to an argon atmosphere.

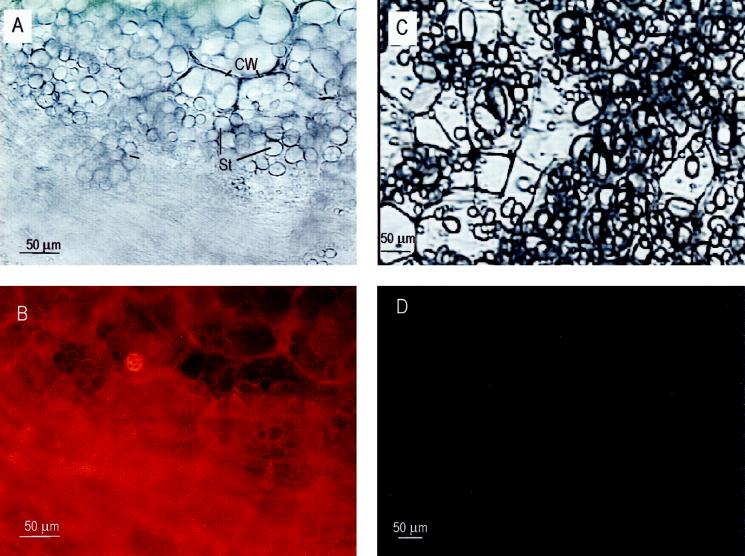

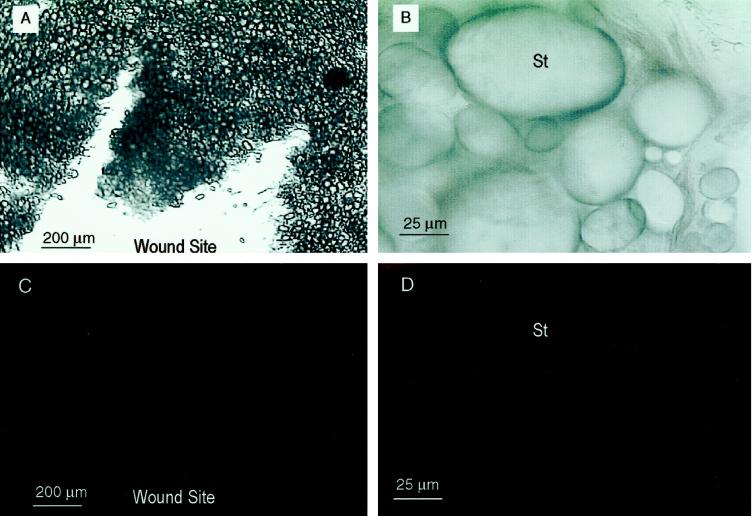

To confirm the dynamic nature of actin filaments in potato tubers, and particularly the paucity of actin filaments in mature quiescent tubers, sections of actively growing tubers and nonwounded postharvest tubers were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Fig. 4); this technique has been extensively used for the detection of actin filaments in a variety of plant species and tissues (Parthasarathy, 1985; Parthasarathy et al., 1985; Kakimoto and Shibaoka, 1987; Traas et al., 1987; Cho and Wick, 1990; Schmit and Lambert, 1990; Abe et al., 1991). Figure 4 demonstrates the abundance of polymerized actin in bulking tuber with rhodamine-dependent fluorescence throughout tuber cells but concentrated near the cell periphery and around starch grains (Fig. 4B). Occasional starch grains appeared to be encircled by fibers with bright fluorescence. This distribution of actin is similar to that observed in developing corn (Zea mays L.) endosperm (Abe et al., 1991; Clore et al., 1996). Rhodamine-dependent fluorescence was consistently absent from nonwounded postharvest tubers (Fig. 4D). These results were consistent with immunoblots of the 4000g pellet fraction and suggested that actin microfilaments depolymerize during establishment of postharvest dormancy.

Figure 4.

Fluorescent detection of actin in actively growing and nonwounded postharvest tubers. A, Light micrograph of an actively growing tuber. B, Fluorescent micrograph of the same actively growing tuber section stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. C, Light micrograph of a nonwounded postharvest tuber. D, Fluorescent micrograph of the same postharvest tuber section stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. CW, Cell wall; St, starch granule.

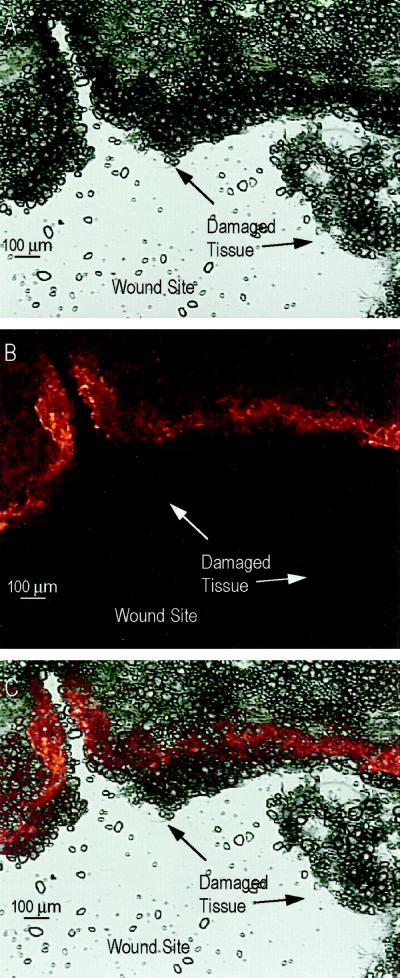

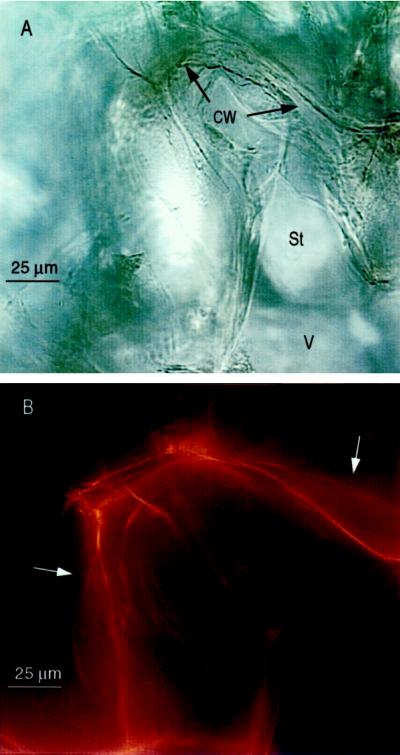

Wounding of postharvest tubers induced a zone of rhodamine-dependent fluorescence in cells around the wound site (Fig. 5). Wounds were generated by insertion of a P-200 pipette tip, and cross-sections were made relative to the plane of the wound. As shown in Figure 5C, the overlay of bright-field and fluorescent micrographs illustrates that this zone lies several cell diameters internal to the wound site and that damaged tissue at the wound margin did not fluoresce. The limitation of polymerized actin to this narrow band of cells near the wound site may explain why actin detected in the 4000g pellet of wounded tubers was only a small fraction of the total cellular actin. Bundles of actin were evident in 12-h-wounded tuber cells, as shown in the high-magnification composite shown in Figure 6 of five serial micrographs taken at depths through the same section. These fibers resemble actin bundles previously observed in plant cells (Parthasarathy, 1985; Parthasarathy et al., 1985; Traas et al., 1987; McCurdy et al., 1988; Schmit and Lambert, 1990). Autofluorescence of phenolics (Yao et al., 1995) was occasionally observed but only using the fluorescein isothiocyanate filter and predominantly at the damaged tissue margin (data not shown). Autofluorescence was not observed using the rhodamine filter (excitation filter 520–545 nm, barrier filter 635 nm; data not shown). Furthermore, the zone of wound-induced fluorescence was abolished by the treatment of 12-h-wounded tubers with 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D for 30 min prior to sectioning (data not shown). These controls indicate that fluorescence was dependent on the presence of both rhodamine-phalloidin and actin filaments.

Figure 5.

Fluorescent detection of actin near the wound site of a 12-h-wounded tuber. A, Light micrograph of a cross-section made relative to the plane of the puncture wound. An arc of the circular wound site is visible. B, Fluorescent micrograph of the same section stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. C, Digital overlay of the fluorescent and bright-field micrographs to show relative position of fluorescent cells.

Figure 6.

Fluorescent detection of actin bundles in a 12-h-wounded tuber. A, High-magnification light micrograph of tuber section. B, Digital overlay of five serial fluorescent micrographs taken at depths of focus through the section. White arrows indicate position of actin bundles not associated with the cell wall (CW). St indicates starch granules in the vicinity of the central vacuole (V).

Rhodamine-dependent fluorescence was greatly diminished by incubation of wounded tubers in a low-oxygen atmosphere. Bundled actin was not observed in sections of 12-h-wounded tuber incubated in argon for 2 h prior to sectioning and fixation (Fig. 7). Low-oxygen-stressed tubers exhibited faint, diffuse fluorescence, although occasional starch grains in the zone maintained fluorescence (Fig. 7). Fluorescence was not observed using anti-tubulin antibodies and rhodamine-conjugated second antibody (data not shown), presumably because of low microtubule abundance. These results agree with the previous immunoblot analyses and suggest that actin polymerizes in response to mechanical wounding and depolymerizes at the onset of low-oxygen stress.

Figure 7.

Micrographs of a 12-h-wounded tuber incubated in an argon atmosphere for 2 h prior to fixation. A and B, Light micrographs of the section. C and D, Fluorescent micrographs of the same fields. Position of the wound site and starch grains (St) are indicated.

Translational Activity Is Depressed by Depolymerization of Microfilaments in Vivo and in Vitro

To determine whether there was a relationship between polymerized actin and wound-induced increases in protein synthesis, we presented tubers with cytochalasin D at the time of wounding. Wounded tubers incubated for 2 h with 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D exhibited [55S]Met incorporation similar to that of tubers labeled immediately upon wounding, which was 3- to 4-fold lower than mock-treated sections of the same 2-h-wounded tubers (Table II). In contrast, 2 h of incubation of tubers with 5 or 10 μm colchicine had no significant effect on translational activity in vivo (Table II). Neither colchicine nor cytochalasin D had a repressive effect on wound-induced RNA synthesis, as assessed by incorporation of [3H]uridine in vivo (Table II), indicating that translational repression by cytochalasin D was not due to a global effect on cellular processes. A small increase in [3H]uridine incorporation was observed in the presence of these drugs. Cytochalasin D and colchicine had almost no effect on run-off translation of tuber polysomes in vitro compared with inhibition by the translocation inhibitor cycloheximide (Table III). These observations are consistent with previous reports that cytochalasin D does not directly inhibit components of the translational machinery in rabbit reticulocyte or HeLa cell lysates but does reduce translation in vivo (Ornelles et al., 1986).

Table II.

Incorporation in vivo of [35S]Met and [3H]uridine by wounded tubers in the presence of cytochalasin D or colchicine

| Treatment | Incorporationaof [35S]Met | Incorporationbof [3H]uridine |

|---|---|---|

| h after wounding | ||

| Mock-treated tubersc | ||

| 0 | 1.22 ± 0.18 | 1.88 ± 0.31 |

| 2 | 6.93 ± 0.45 | 4.21 ± 0.58 |

| 12 | 11.54 ± 1.51 | 4.53 ± 0.63 |

| Cytochalasin D-treated tubersd | ||

| 2 | 1.62 ± 0.32 | 5.65 ± 0.72 |

| 12 | 3.87 ± 0.82 | 5.44 ± 0.62 |

| Colchicine-treated tuberse | ||

| 2 | 6.55 ± 0.69 | 5.31 ± 0.66 |

| 12 | 10.61 ± 0.93 | 5.27 ± 0.72 |

Incorporation of [35S]Met was measured as TCA-precipitable counts per minute (× 106) per gram fresh weight in extracts prepared after a 30-min labeling at 20°C.

Incorporation of [3H]uridine was measured as TCA-precipitable counts per minute (× 104) per gram fresh weight in extracts prepared after a 30-min labeling at 20°C. TCA precipitation assays were performed in triplicate. Activity is the mean ± se for three independent trials.

[35S]Met (0.25 mCi) or [3H]uridine (0.25 mCi) was presented to tuber wounds at the time of wounding (0 h), 2 h after wounding, or 12 h after wounding. Mock-treated tubers were presented with 50 μL of 1% DMSO 2 h prior to the addition of label.

Cytochalasin D-treated tubers were presented with 50 μL of 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D in 1% DMSO 2 h prior to addition of label.

Colchicine-treated tubers were presented with 50 μL of 10 μm colchicine 2 h prior to addition of label.

Table III.

Effect of cytochalasin D and colchicine on run-off translation of isolated polysomes and the 4000g pellet fraction prepared from 2-h-wounded tubers

| Treatment | Incorporationa |

|---|---|

| Isolated polysomesb | |

| Control | 15.22 ± 0.55 |

| 32 μg mL−1 Cytochalasin D | 14.98 ± 0.73 |

| 10 μm Colchicine | 14.24 ± 0.65 |

| 50 μm Cycloheximide | 0.52 ± 0.05 |

| 4000g Pelletc | |

| Control | 6.38 ± 0.52 |

| 32 μg mL−1 Cytochalasin D | 2.46 ± 0.42 |

| 10 μm Colchicine | 5.75 ± 0.55 |

| 50 μm Cycloheximide | 0.47 ± 0.04 |

Translational run-off reactions were performed as described by Vayda (1995) using 25 μCi [35S]Met per reaction.

Aliquots of each reaction were taken in triplicate at the start of the reaction and after 5, 10, and 20 min at 20°C. Incorporation values reported are TCA-precipitable counts per minute (× 104) per 1-μL aliquot taken after 20 min of reaction. Activity is the mean ± se for three independent trials.

An aliquot of the polysome pellet fraction containing 10 μg of RNA used as the template.

An aliquot of the 4000g pellet fraction containing 20 μg of RNA used as the template.

The presence of 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D did reduce run-off translation in vitro using the 4000g pellet as the template. Table III shows that polysomes present in the 4000g pellet of 2-h-wounded tubers directed incorporation of [35S]Met in run-off translation reactions, albeit to a lesser extent than an equivalent mass of isolated polysomes extracted from tissue in the presence of 400 mm KCl (Vayda, 1995). The addition of 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D to the resuspended 4000g pellet reduced run-off translation 2- to 3-fold (Table III). In contrast, addition of colchicine to 10 μm did not have a significant effect. These results indicate that cytochalasin D diminished translation directed by polysomes in the 4000g pellet fraction but did not affect translation of isolated polysomes lacking polymerized actin.

CONCLUSIONS

Three observations lead us to conclude that the presence of F-actin affects translational activity in wounded potato tubers. Rapidly sedimenting actin (Fig. 3) and fluorescently tagged actin (Figs. 5, 6, and 7) of postharvest tuber tissue varied in response to wounding and low-oxygen stress and correlated with translational activity of the tissue (Table I). More conclusively, translational activity in vivo (Table II) was reduced by treatment of tubers with cytochalasin D, which prevented wound-induced polymerization of actin (Fig. 2). Furthermore, cytochalasin D reduced run-off translation of polysomes present in the 4000g pellet fraction of wounded tubers (Table III). However, cytochalasin D did not reduce translation of isolated polysomes, which did not contain actin, prepared from the same tissue by extraction in buffer containing 400 mm KCl (Table III). These results indicate that disruption of actin filaments reduced translational activity and, conversely, suggest that wound-induced polymerization of actin may stimulate protein synthesis in vivo.

Actin filaments may enhance protein synthesis by providing a scaffold for specific assembly of the translational machinery. In addition to polysomes (Ito et al., 1994), other translational components have been found in association with microfilaments and/or microtubules. These include eEF1A (Demma et al., 1990; Condeelis, 1995; Clore et al., 1996), the plant-specific initiation factor eIFiso4F (Bokros et al., 1995; Hugdahl et al., 1995), initiation factors 2, 3, and 4A (Howe and Hershey, 1984; Heuijerjans et al., 1989), eEF2 (Bektas et al., 1994), and amino acyl-tRNA synthetases (Mirande et al., 1985). eEF1A has been shown to colocalize with actin filaments in maize endosperm in situ (Clore et al., 1996) and was independently isolated as an actin-binding protein (Demma et al., 1990; Condeelis, 1995), as a microtubule-associated protein, the binding of which in vitro is affected by calcium (Durso and Cyr, 1994b), and as a factor that, when phosphorylated, mediates a 2-to 3-fold increase in activity of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (Yang et al., 1993; Yang and Boss, 1994). The latter enzyme has been shown to be associated with the cytoskeleton of plants (Xu et al., 1992). In accord with these previous studies, immunoblot analyses indicated that eEF1A was present almost exclusively in the 4000g pellet of wounded aerobic tubers and was displaced to the 4000g supernatant by resuspension of pellets in 200 mm KCl or treatment of tubers with 32 μg mL−1 cytochalasin D (W. Zhou, J.K. Morelli, and M.E. Vayda, unpublished results). Furthermore, sedimentation of eEF1A with the 4000g pellet was severely reduced at the onset of low-oxygen stress, although total cellular eEF1A abundance did not change (W. Zhou, J.K. Morelli, and M.E. Vayda, unpublished results).

These observations provide support for the hypothesis that components of the protein synthetic apparatus localize to a microenvironment provided by the cytoskeleton. Actin appears to be responsible for this association in postharvest potato tubers, because only minute quantities of tubulin were detected in the 4000g pellet and colchicine did not have an effect on protein synthesis in vivo or by polysomes in the 4000g pellet. Association of translational components with actin filaments may limit diffusion distances between factors and thereby increase translational efficiency. Conversely, depolymerization of actin filaments may disperse components of the translational apparatus and reduce translation initiation or elongation rates. In this way, polymerization or depolymerization of actin filaments in response to changing environmental conditions could be one of several factors contributing to changes in translational activity. This is not to say that the only purpose of actin polymerization or depolymerization during stress conditions is regulation of translational activity. Luby-Phelps (1993) proposed that dense cytoskeletal structures may exclude polysomes from some cytoplasmic domains. But one consequence of actin polymerization upon wounding and depolymerization at the onset of low-oxygen stress could be the global effects on protein synthetic activity by altering the ratio of free polysomes to cytoskeleton-associated polysomes.

The basis for changes in the actin polymerization state in response to environmental stressors is not known. Lactate accumulates rapidly at the onset of low-oxygen stress (Roberts et al., 1984; Sieber and Brändle, 1991; Vayda et al., 1995) and cytoplasmic pH decreases 0.5 unit within 20 min of low-oxygen stress in corn roots (Roberts et al., 1984; Xia and Roberts, 1994). The onset of low-oxygen stress also triggers the release of calcium from internal stores, most likely from mitochondria (Subbaiah et al., 1994). Similarly, mechanical wounding of plant tissue elicits voltage change and calcium influx across the plasma membrane (Van Sambeek and Pickard, 1976; Roblin, 1985; Davies, 1987, 1993). Both of these phenomena are likely to alter protein kinase or protein phosphatase activities of signal transduction cascades, which could perturb equilibria among actin polymers, actin monomers, and actin-binding proteins. These activities may also coordinate further fine regulation of protein synthesis, e.g. by phosphorylation of S6 or of acidic ribosomal proteins, which may enhance translational activity. Conversely, phosphorylation may contribute to translational arrest by modification of eIF4A, as has been observed in corn roots during hypoxia (Webster et al., 1991a), or by modification of eEF2, which occurs in animal cells in response to increased calcium or decreased pH (Ryazanov et al., 1988; Mitsui et al., 1993). Protein synthesis is likely to be regulated by several mechanisms. Our results suggest that one of these mechanisms is the association of the translational apparatus with polymerized actin to increase activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to sincerely thank David Frey for excellent technical assistance with fluorescence microscopy (conducted at the Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), Dr. Eric Davies for helpful discussions, and Dr. Karen Browning for generously providing the anti-eEF1A antiserum.

Abbreviations:

- CSB

cytoskeletal stabilizing buffer

- eEF1A

eukaryotic elongation factor 1α

- eEF2

eukaryotic elongation factor 2

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- S6

small ribosomal subunit protein 6

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-National Research Initiative Grant Program (grant no. 95-37100-1564) and the Maine Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Project (grant no. ME38402). This is publication no. 2180 of the Maine Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abe S, Davies E. Isolation of F-actin from pea stems: evidence from fluorescence microscopy. Protoplasma. 1991;163:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Abe S, Davies E. Methods for isolation and analysis of the cytoskeleton. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;50:223–236. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe S, Ito Y, Davies E. Co-sedimentation of actin, tubulin and membranes in the cytoskeleton fractions from peas and mouse 3T3 cells. J Exp Bot. 1992;43:941–949. [Google Scholar]

- Abe S, You W, Davies E. Protein bodies in corn endosperm are enclosed by and enmeshed in F-actin. Protoplasma. 1991;165:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J, Freeling M. Hypoxic stress-induced changes in ribosomes of maize seedling roots. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:1237–1243. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.3.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ. High resolution distribution of mRNA within the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biochem. 1993;52:127–133. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240520203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Singer RH. mRNA and cytoskeletal filaments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Taneja KL, Kislauskis EH, Sundell CL, Powers CM, Ross A, Singer RH. Actin filaments and the spatial positioning of mRNAs. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;358:183–189. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2578-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bektas M, Nurten R, Gürel Z, Sayers Z, Bermek E. Interactions of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 with actin: a possible link between protein synthetic machinery and cytoskeleton. FEBS Lett. 1994;356:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt AM, Knowler JT. Tissue distribution and change in potato starch phosphorylase mRNA levels in wounded tissue and sprouting tubers. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:971–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel D, Pachter JS. “In situ” translation: use of the cytoskeletal framework to direct cell-free protein synthesis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1991;27A:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02630897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokros CL, Hugdahl JD, Kim H-H, Hanesworth VR, van Heerden A, Browning KS, Morejohn LC. Function of the p86 subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor (iso)4F as a microtubule-associated protein in plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7120–7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulter W, Cook L, Vayda ME. Hypoxic stress inhibits multiple aspects of the potato tuber wound response. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:264–270. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S-O, Wick SM. Distribution and function of actin in the developing stomatal complex of winter rye (Secale cereale cv. Puma) Protoplasma. 1990;157:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Clore AM, Dannenhoffer JM, Larkins BA. EF-1α is associated with a cytoskeletal network surrounding protein bodies in maize endosperm cells. Plant Cell. 1996;8:2003–2014. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.11.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J. Elongation factor 1α, translation and the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:169–170. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DN, Muday GK. NPA binding activity is peripheral to the plasma membrane and is associated with the cytoskeleton. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1941–1953. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby JS, Vayda ME. Stress-induced translational control in potato tubers may be mediated by polysome-associated proteins. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1013–1023. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.9.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E. Action potentials as multifunctional signals in plants: a hypothesis attempting to unify apparently disparate wound responses. Plant Cell Environ. 1987;10:623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Davies E. Intercellular and intracellular signals and their transduction via the plasma membrane-cytoskeleton interface. Semin Cell Biol. 1993;4:139–147. doi: 10.1006/scel.1993.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E, Corner EC, Lionberger JM, Stankovic B, Abe S. Cytoskeleton-bound polysomes in plants. III. Polysome-cytoskeleton-membrane interactions in corn endosperm. Cell Biol Int. 1993;17:331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Davies E, Gillingham BD, Ito Y, Abe S. Evidence for the existence of cytoskeleton-bound polysomes in plants. Cell Biol Int. 1991;15:973–981. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(91)90147-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E, Ramaiah KVA, Abe S. Wounding inhibits protein synthesis yet stimulates polysome formation in aged, excised pea epicotyls. Plant Cell Physiol. 1986;27:1377–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Davies E, Schuster A. Intercellular communication in plants: evidence for a rapidly generated, bidirectionally transmitted wound signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2422–2426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Butler W, Vayda ME (1990) Molecular responses to environmental stresses and their relationship to soft rot. In ME Vayda, WD Park, eds, The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Potato. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 71–87

- Demma M, Warren V, Hock R, Dharmawardhane S, Condeelis J. Isolation of an abundant 50,000-dalton actin filament bundling protein from Dictyostelium amoebae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso NA, Cyr RJ. Beyond translation: elongation factor 1-α and the cytoskeleton. Protoplasma. 1994a;180:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Durso NA, Cyr RJ. A calmodulin-sensitive interaction between microtubules and a higher plant homolog of elongation factor-1α. Plant Cell. 1994b;6:893–905. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.6.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennoy SL, Bailey-Serres J. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in oxygen-deprived roots of maize. Plant J. 1995;7:287–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Hernandez M, Davies E, Baskin TI, Staswick PE. Association of plant P40 protein with ribosomes is enhanced when polyribosomes form during periods of active tissue growth. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:559–568. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habben JE, Moro GL, Hunter BG, Hamaker BR, Larkins BA. Elongation factor 1 alpha concentration is highly correlated with the lysine content of maize endosperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8640–8644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh J. Translation and the cytoskeleton: a mechanism for targeted protein synthesis. Mol Biol Rep. 1994;19:233–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00986965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh JE, Campbell GP, Whitelaw PF. c-myc mRNA in cytoskeletal-bound polysomes in fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1991;274:607–609. doi: 10.1042/bj2740607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh JE, Pryme IF. Evidence that insulin increases the proportion of polysomes that are bound to the cytoskeleton in 3T3 fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:62–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh JE, Pryme IF. Interaction between mRNA, ribosomes and the cytoskeleton. Biochem J. 1991;277:1–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2770001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuijerjans JH, Peiper FR, Ramaekers FCS, Timmermans LJM, Kuijpers H, Bloemendal H, Van Venrooij WJ. Association of mRNA and eIF-2α with the cytoskeleton in cells lacking vimentin. Exp Cell Res. 1989;181:317–330. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe JG, Hershey JW. Translation initiation factor and ribosome association with the cytoskeletal framework fraction from HeLa cells. Cell. 1984;37:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugdahl JD, Bokros CL, Morejohn LC. End-to end annealing of plant microtubules by the p86 subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor-(iso)4F. Plant Cell. 1995;7:2129–2138. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Abe S, Davies E. Co-localization of cytoskeleton proteins and polysomes with a membrane fraction from peas. J Exp Bot. 1994;45:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies HBJ, Thomas G. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation and signal transduction. In: Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational Control. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T, Shibaoka H. Actin filaments and microtubules in the preprophase band and phragmoplast of tobacco cells. Protoplasma. 1987;140:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-Y, Key JL. Dissociation and reassembly of polyribosomes in relation to protein synthesis in the soybean root. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy DW, Sammut M, Gunning BES. Immunofluorescent visualization of arrays of transverse cortical actin microfilaments in wheat root-tip cells. Protoplasma. 1988;147:204–206. [Google Scholar]

- Mirande M, LeCorre D, Louvard D, Reggio H, Pailliez J-P, Waller J-P. Association of an amino-acyl-transfer RNA synthetase complex and of phenylalanyl-transfer RNA synthetase with the cytoskeletal framework fraction from mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res. 1985;156:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(85)90264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui K-I, Brady M, Palfrey HC, Nairn AC. Purification and characterization of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III from rabbit reticulocytes and rat pancreas. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13422–13433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli JK, Shewmaker CK, Vayda ME. Biphasic stimulation of translational activity correlates with induction of translation elongation factor 1 subunit a upon wounding in potato tubers. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:897–903. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.3.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli JK, Vayda ME. Mechanical wounding of potato tubers induces replication of potato virus S. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1996;49:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ornelles DA, Fey EG, Penman S. Cytochalasin releases mRNA from the cytoskeletal framework and inhibits protein synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1650–1662. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.5.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteris E, Apostolakos P, Galatis B. The organization of F-actin in root tip cells of Adiantum capillus veneris through the cell cycle. Protoplasma. 1992;170:128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy MV. F-actin architecture in coleoptile epidermal cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1985;39:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy MV, Perdue TD, Witztum A, Alvernaz J. Actin network as a normal component of the cytoskeleton in many vascular plant cells. Am J Bot. 1985;72:1318–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Pokalsky AR, Hiatt WR, Ridge N, Rasmussen R, Houck CM, Shewmaker CK. Structure and expression of elongation factor 1a in tomato. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4661–4673. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JKM, Callis J, Jardetzy O, Walbot V, Freeling M. Cytoplasmic acidosis as a determinant of flooding intolerance in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6029–6033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.6029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roblin G. Analysis of the variation potential induced by wounding in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:455–461. [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanov AG, Shestakova EA, Natapov PG. Phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 by EF-2 kinase affects rate of translation. Nature. 1988;334:170–173. doi: 10.1038/334170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf KD, Nover L. Heat-shock-induced alterations of ribosomal protein phosphorylation in plant cell cultures. Cell. 1982;30:427–437. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmit A-C, Lambert AM. Microinjected fluorescent phalloidin in vivo reveals the F-actin dynamics and assembly in higher plant mitotic cells. Plant Cell. 1990;2:129–138. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster AM, Davies E. Ribonucleic acid and protein metabolism in pea epicotyls. II. Response to wounding in aged tissue. Plant Physiol. 1983;73:817–821. doi: 10.1104/pp.73.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber M, Brändle R. Energy metabolism in rhizomes of Acorus calamus (L.) and tubers of Solanum tuberosum (L.) with regard to their anoxia tolerance. Bot Acta. 1991;104:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Subbaiah CC, Bush DS, Sachs MM. Elevation of cytosolic calcium precedes anoxic gene expression in maize suspension-cultured cells. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1747–1762. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja KL, Lifshitz LM, Fay FS, Singer RH. Poly(A) RNA codistribution with microfilaments: evaluation by in situ hybridization and quantitative digital imaging microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1245–1260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh BH, Lolait SJ, Mathy JP, Baum R. Association of mitochondria with intermediate filaments and of polysomes with cytoplasmic actin. Cell Tissue Res. 1980;211:163–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00233731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traas JA, Doonan JH, Rawlins DJ, Shaw PJ, Watts J, Lloyd CW. An actin network is present in the cytoplasm throughout the cell cycle of carrot cells and associates with the dividing nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:387–395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursin VM, Irvine JM, Hiatt WR, Shewmaker CK. Developmental analysis of elongation factor eEF-1α expression in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell. 1991;3:583–591. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.6.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sambeek JW, Pickard BG. Mediation of rapid electrical, metabolic, transpirational and photosynthetic changes by factors released from wounds. Can J Bot. 1976;54:2651–2661. [Google Scholar]

- Vayda ME. Assessment of translational regulation by run-off translation of polysomes in vitro. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;50:349–359. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vayda ME, Morelli JK (1994) Regulation of translation in potato tubers in response to environmental stress. In WR Belknap, ME Vayda, WD Park, eds, The Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Potato, Ed 2. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 187–208

- Vayda ME, Schaeffer HJ. Hypoxic stress inhibits the appearance of wound-response proteins in potato tubers. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:805–809. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vayda ME, Shewmaker CK, Morelli JK. Translational arrest in hypoxic potato tubers is correlated with the aberrant association of elongation factor EF-1α with polysomes. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;28:751–757. doi: 10.1007/BF00021198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C, Gaut RL, Browning KS, Ravel JM, Roberts JKM. Hypoxia enhances phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A in maize root tips. J Biol Chem. 1991a;266:23341–23346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C, Kim C-Y, Roberts JKM. Elongation and termination reactions of protein synthesis on maize root tip polyribosomes studied in a homologous cell-free system. Plant Physiol. 1991b;96:418–425. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.2.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J-H, Roberts JKM. Improved cytoplasmic pH regulation, increased lactate efflux, and reduced cytoplasmic lactate levels are biochemical traits expressed in root tips of whole maize seedlings acclimated to a low-oxygen environment. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:651–657. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Lloyd CW, Staiger CJ, Drøbak BK. Association of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase with the plant cytoskeleton. Plant Cell. 1992;4:941–951. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.8.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Boss WF. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase by the protein activator PIK-A49: activation requires phosphorylation of PIK-A49. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3852–3857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Burkhart W, Cavallius J, Merrick WC, Boss WF. Purification and characterization of a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase activator in carrot cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:392–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao K, De Luca V, Brisson N. Creation of a metabolic sink for tryptophan alters the phenylpropanoid pathway and the susceptibility of potato to Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1787–1799. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]