Abstract

Recent literature has reported increased accuracy of Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification (TMA)-based analyte-specific reagent (ASR) testing in female populations. A retrospective investigation assessed 7,277 female first-void urine, cervical, or vaginal specimens submitted from a high-prevalence sexually transmitted infection (STI) community to characterize prevalence of disease etiologies. The most common STI phenotype reflected detection of solely T. vaginalis (54.2% of all health care encounters that resulted in STI detection). In females with detectable T. vaginalis, codetection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae occurred in 7.8% and 2.7% of health care encounters, respectively. The mean age of women with detectable T. vaginalis (30.6) was significantly higher than those for women with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae (22.3 and 21.6, respectively; P < 0.0001). T. vaginalis was the predominant sexually transmitted agent in women over the age of 20 (P < 0.0002). C. trachomatis was the most commonly detected agent in females under the age of 21, particularly from cervical specimens. However, first-void urine detection rates for T. vaginalis and C. trachomatis within this age demographic demonstrated no difference (P = 0.92). While overall and cervical specimen-derived detection of T. vaginalis within African American majority geographical locales outweighed that within majority Caucasian geographical regions (P ≤ 0.004), this difference was not noted with first-void urine screening (P = 0.54). Health care professionals can consider TMA-based T. vaginalis screening for a wide age range of patients; incorporation of first-void urine specimens into screening algorithms can potentiate novel insight into the epidemiology of trichomoniasis.

INTRODUCTION

Past estimates of trichomoniasis prevalence both worldwide (180 million cases) and in the United States (3 to 5 million annual cases) (28) were based on diagnostic modalities that possess suboptimal accuracy. Recent data indicate increased sensitivity of transcription-mediated amplification (TMA)-based detection of Trichomonas vaginalis compared to that of wet mount microscopy (12, 18, 19, 22), culture (12, 22), nucleic acid hybridization (1), and antigen detection (12). In spite of trichomoniasis largely presenting as vulvovaginitis, T. vaginalis analyte-specific reagent (ASR)-derived data describe the value of endocervical samplings for molecular T. vaginalis detection (19, 22, 24). In addition, preliminary data suggest increased T. vaginalis detection from first-void urine specimens compared to that from vaginal and cervical specimens (1, 21).

T. vaginalis ASR is now formatted as the APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis assay, with U.S. Food and Drug Administration indications for female first-void urine, genital swab, and gynecological specimens (24). The method has been the basis for at least two female trichomoniasis epidemiological assessments (1, 7). However, sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevalence limitations were inherent to these two reports. Napierala et al. (21) summarized operational characteristics of T. vaginalis ASR using a high-prevalence STI metropolitan area. That study served as the basis for the presented investigation. Objectives of the current study include a comparative STI prevalence assessment using highly sensitive TMA. In addition, we seek to further characterize a role for first-void urine in the context of laboratory diagnostics and epidemiological assessment.

(Results of this work were previously presented, in part, at the 111th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, New Orleans, LA, 21 to 24 May 2011.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting.

United States metropolitan statistical area (MSA) data document a long-standing trend of high STI prevalence in the Milwaukee (WI) metropolitan area (2). The Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis MSA chlamydia rate was 738.1 per 100,000 population in 2010. This was the second highest in the United States and 63.1% higher than the national cumulative MSA rate of 452.6 per 100,000 population. This MSA also had the second-highest gonorrhea rate among United States MSAs (219.6 per 100,000 population; the national MSA rate was 113.9 per 100,000 population). Testing was performed at Wheaton Franciscan Laboratory, a central laboratory serving five Milwaukee metropolitan hospitals and an approximately 70-clinic metropolitan outpatient physician group. T. vaginalis ASR was offered to clinicians as a stand-alone assay or in conjunction with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae molecular screening.

Specimen collection.

Primary endocervical or clinician-collected vaginal specimens were deposited into APTIMA swab specimen transport tubes per the APTIMA Combo 2 assay (Gen-Probe, Incorporated, San Diego, CA) package insert protocol. Alternatively, approximately 2-ml aliquots of first-void female urine were added to APTIMA urine specimen transport tubes within 24 h of specimen procurement. In some instances, vaginal discharges were sampled by clinicians with a Dacron swab and placed into 1.0 ml of 145 mM NaCl. When T. vaginalis ASR was requisitioned following negative wet mount microscopy, 200-μl aliquots of suspensions demonstrating no motile trichomonads were transferred into specimen transport tubes (18).

Primary molecular screening assays.

Nonautomated T. vaginalis ASR, detecting organism-specific 16S rRNA via target capture, TMA, and chemiluminescent hybridization protection, was previously validated on female genital and urine specimens in conjunction with a proprietary alternative-target TMA-based confirmatory assay (Gen-Probe). Relative light unit values (RLU) ≥50,000, as determined by stand-alone luminometry, were interpreted as positive. A similar method, the APTIMA Combo 2 assay, was used for detection of N. gonorrhoeae-specific 16S rRNA and C. trachomatis-specific 23S rRNA (6).

Study.

The Wheaton Franciscan Healthcare institutional review board approved this 3-year analysis of T. vaginalis ASR testing. Greater than 98% of all specimens were also screened for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae. The specimen source, screening result, age of the patient, race/ethnicity of the patient (when available), and ZIP code of patient residence were collected. Five-digit ZIP code tabulation areas were accessed through the 2000 United States Census database (http://factfinder.census.gov) to provide a race/ethnicity distribution. The STI phenotype (permutations of T. vaginalis, N. gonorrhoeae, and/or C. trachomatis TMA-based detection) was computed from any health care encounter that resulted in detection of at least one STI.

Statistical analysis.

The significance test of proportions determined if differences in rates of positive screening results, proportions of specimen sources, or STI phenotypes were significant. The t test for independent samples determined if differences in mean patient age associated with positive results were significant between STIs. The alpha level was set at 0.05 before the investigations commenced, and all P values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Female STI profiling.

A total of 7,277 specimens yielded a female T. vaginalis detection rate (9.3%) that exceeded those for C. trachomatis (5.7%) and N. gonorrhoeae (1.4%) (both P values were <0.0002). A total of 7,149 of these specimens came from health care encounters that resulted in TMA-based testing for all three STIs; 1,036 (14.5%) encounters resulted in detection of at least one STI. Such detection occurred more frequently with first-void urine (19.5%) (Table 1) than with other sources (P < 0.0002).

TABLE 1.

Sexually transmitted infection phenotypes, determined by transcription-mediated amplification-based assays specific for Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, within screened females positive for at least one STI

| Phenotype no. | Sexually transmitted infection phenotypea |

Percentage of patients with each phenotype, delineated by specimen source |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Chlamydia trachomatis | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Cervixb | First-void urinec | Vaginad | Totale | |

| 1 | + | − | − | 53.5 | 58.0 | 59.3 | 54.2 |

| 2 | + | + | − | 6.8 | 4.9 | 7.7 | 6.6 |

| 3 | + | + | + | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| 4 | + | − | + | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

| 5 | − | + | − | 30.1 | 23.5 | 29.7 | 29.1 |

| 6 | − | − | + | 4.2 | 9.9f | 0.0 | 4.7 |

| 7 | − | + | + | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.2 |

+, positive nucleic acid amplification screen; −, negative nucleic acid amplification screen.

A total of 783 (14.0%) encounters had at least one STI.

A total of 162 (19.5%) encounters had at least one STI.

A total of 91 (12.5%) encounters had at least one STI.

A total of 1,036 (14.5%) encounters had at least one STI.

P value of ≤0.0003 compared to detection of solely N. gonorrhoeae from vagina or cervix.

In terms of individual STI agents, STI phenotype differences between first-void urine and genital swab collections were minimal (P ≥ 0.09) (Table 1), with the exception of increased detection of N. gonorrhoeae from first-void urine (P ≤ 0.0003). Increased detection of solely T. vaginalis (54.2% in a combined first-void urine and genital swab data set) was noted compared to detection of solely C. trachomatis (29.1%; P < 0.0002). Codetection rates for other STIs with T. vaginalis ranged from 5.5% (first-void urine) to 8.2% (cervix) for C. trachomatis and from 1.8% (first-void urine) to 2.9% (cervix) for N. gonorrhoeae (Table 1).

Demographics of females with detectable T. vaginalis.

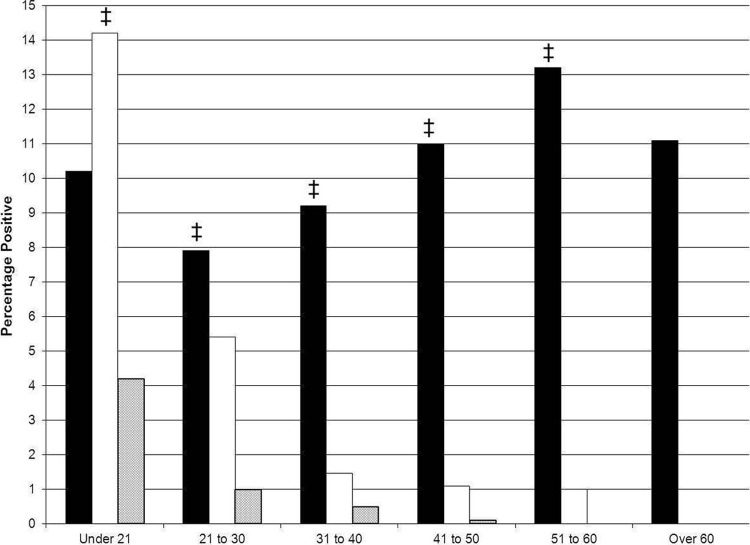

Detection of C. trachomatis peaked in females less than 21 years of age (14.2%) (Fig. 1) and exceeded detection of other STIs (P ≤ 0.001). Detection of T. vaginalis was more frequent than detection of C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae for ages 21 and older. This pattern was independent of specimen source (data not illustrated). The age range of T. vaginalis detection was 15 to 79 (median, 28); the mean age of 30.6 was greater than those for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (22.3 and 21.6, respectively; P < 0.0001).

Fig 1.

Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis (solid bars), Chlamydia trachomatis (open bars), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (shaded bars) among 7,277 females screened by transcription-mediated amplification-based methods, delineated by age. ‡ indicates comparisons between T. vaginalis and C. trachomatis detection rates in which P was ≤0.001.

From ages 21 to 30, detection of T. vaginalis was increased compared to detection of C. trachomatis, regardless of specimen source (P ≤ 0.04) (Table 2). This paradigm held true for older populations (data not illustrated). In contrast, for the under-21 population, detection of C. trachomatis (15.0%) was greater than detection of T. vaginalis (10.0%) only from cervical specimens (P = 0.0006) and demonstrated no detection difference from first-void urine specimens (P = 0.92).

TABLE 2.

Detection of Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachomatis, or Neisseria gonorrhoeae among young females screened by transcription-mediated amplification-based methods, delineated by age and specimen source

| Age range of females (yr) | Specimen source | Transcription-mediated amplification-based screening |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of n | Percentage detection |

P valueb | ||||

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Chlamydia trachomatis | Neisseria gonorrhoeaea | ||||

| Under 21 | Cervix | 1,034–1,041 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 4.4 | 0.0006 |

| Vagina | 143–144 | 9.7 | 14.7 | 0.7 | 0.20 | |

| First-void urine | 276–278 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 5.1 | 0.92 | |

| 21–30 | Cervix | 2,400–2,424 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 0.04 |

| Vagina | 301–305 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 0.004 | |

| First-void urine | 331–343 | 13.1 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 0.006 | |

All N. gonorrhoeae detection rates were significantly lower than those for both T. vaginalis and C. trachomatis (P ≤ 0.01).

Relative to the T. vaginalis and C. trachomatis detection rates.

Race/ethnicity assessment of T. vaginalis detection in females.

For females with detectable T. vaginalis from whom race/ethnicity data were available, 92.7% were African American. This proportion was independent of specimen type (P ≥ 0.11; data not illustrated). Eleven Milwaukee County ZIP code tabulation areas yielded >74% of all T. vaginalis ASR screens. Characteristics of this subset, in terms of STI phenotype and specimen submission ratio, were representative of the overall data set (data not illustrated). With respect to specimen source submission, significant differences did not exist between African American and Caucasian majority geographical regions (P ≥ 0.06) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Delineation of 11 Milwaukee County ZIP code tabulation areas responsible for significant Trichomonas vaginalis female screening into majority African American or Caucasian geographical areas, with characterization of the two subgroups

| Parameter | Value in geographical regions with race majority |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| African Americana | Caucasianb | ||

| Percentage of specimen submissionsc | |||

| Cervix | 77.1 | 76.8 | 0.84 |

| Vagina | 9.6 | 11.4 | 0.06 |

| Combined genitald | 86.7 | 88.2 | 0.15 |

| First-void urine | 13.3 | 11.8 | 0.15 |

| T. vaginalis detection rate (%) | |||

| Overall | 11.7 | 9.0 | 0.004 |

| Cervix | 11.6 | 8.1 | 0.002 |

| Vagina | 9.4 | 11.1 | 0.53 |

| Combined genital | 11.4 | 8.5 | 0.005 |

| First-void urine | 14.4 | 12.5 | 0.54 |

The mean difference between African American and Caucasian populations was 43.9% per ZIP code tabulation area (n = 7).

The mean difference between Caucasian and African American populations was 32.6% per ZIP code tabulation area (n = 4).

Percentage of all submissions.

Sum of cervical and vaginal specimens.

In general, T. vaginalis detection from the African American majority geographical region was increased over that in majority Caucasian areas when testing cervical specimens (P = 0.002) (Table 3). This association extended to a compilation of cervical and vaginal specimens (P = 0.005). In contrast, first-void urine detection of T. vaginalis revealed no significant difference between African American and Caucasian majority geographical areas (P = 0.54) (Table 3). Similar paradigms applied to both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae detection (data not illustrated).

DISCUSSION

TMA-based assays demonstrate high sensitivity for detection of T. vaginalis (1, 19, 22, 24). This paradigm has been applied to clinical practice. Napierala et al. (21) described a clinical testing experience involving nearly 8,000 patients, with less than 2% presenting for emergency care. Practitioners utilized T. vaginalis ASR at an increased annual rate for both female and male screening. T. vaginalis ASR availability increased screening rates not only for T. vaginalis but also for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (17). The subacute nature of this population, suggesting a substantial proportion of asymptomatic females, is relevant. A number of publications have documented T. vaginalis detection from asymptomatic patients (22, 24, 25, 27). In one of these studies, Schwebke and Hook (25) reported an increased T. vaginalis detection rate in asymptomatic males compared to that in males with symptoms (P = 0.009).

The T. vaginalis detection rate (9.3%) exceeded the detection rates of C. trachomatis (5.7%) and N. gonorrhoeae (1.4%) (P values of <0.0002 for both) in the current assessment of female epidemiology. Andrea and Chapin (1) documented increased T. vaginalis detection (5.1% rate) compared to detection of C. trachomatis (3.4%). However, this study was performed in a low-prevalence STI population. Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates for the Providence-New Bedford-Fall River (RI and MA) MSA were 297.3 and 23.9 per 100,000 population, respectively (2). TMA-derived T. vaginalis, C. trachomatis, and N. gonorrhoeae detection rates were reported by Ginocchio et al. (7) at 8.7%, 6.7%, and 1.7%, respectively. While that clinical trial had value because study site enrollment represented several geographical regions, a number of study centers were not high-prevalence centers of STIs. As examples, the Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington (TX), Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana (CA), San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont (CA), Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta (GA), and Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington (MN and WI) MSAs ranked 27th, 30th, 32nd, 33rd, and 43rd, respectively, among major metropolitan centers for chlamydia in 2010 (2). In contrast, our data from a high-prevalence STI community verify previous findings (1, 7) regarding the comparative prevalence of T. vaginalis to other STI.

The value of our large data set also applies to age delineation of T. vaginalis detection. Past studies (11, 27) showed increased T. vaginalis prevalence in older age groups but did not have the benefit of highly sensitive TMA (3, 13, 23). One account derived from TMA analysis (1) also reported this phenomenon but did not demonstrate C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae detection in patients beyond ages 26 to 30. A larger data set (7) revealed baseline C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae detection in women over age 30 and suggested that T. vaginalis prevalence was lowest in females under age 40. In contrast, our data demonstrate increased T. vaginalis detection compared to that of C. trachomatis in multiple age decades starting with age 21 (Fig. 1). Ginocchio et al. (7) used the arbitrary age classification of >50 years for their T. vaginalis detection endpoint, whereas our data chronicle not only increased T. vaginalis detection in women aged 51 to 60 years but also a detection rate >11% in women over age 60. Previous data (1, 7) were compromised to a degree by the size of study or settings that included lower-prevalence STI communities. Our findings, derived from over 7,000 patients in a high-prevalence STI metropolitan area, both confirm and extend previous TMA-based epidemiological assessments.

Similar to previous reports (7, 15, 26, 27), a majority of females with detectable T. vaginalis in this study were African American. One inherent limitation was that not all laboratory requisitions provided race/ethnicity data (data were available for 98% of patients yielding a positive T. vaginalis result). Patient residence ZIP codes were therefore translated into general race/ethnicity representations of local environments via United States census data. Sampling biases did not exist between the African American and Caucasian majority geographical areas in terms of specimen distribution per geographical region (P ≥ 0.06) (Table 3). Of particular interest, first-void urine T. vaginalis detection rates did not vary between the two geographical regions (P = 0.54). While secondary limitations (residence migration during census intervals, sexual partners in other ZIP code tabulation areas) can confound this adjunctive approach, the apparent community-wide distribution of the T. vaginalis protozoan may be a by-product of enhanced analytical sensitivity of T. vaginalis ASR. An analogous study in males noted similar findings (20). Taken together, these findings may have significant clinical and public health ramifications.

Data suggesting a community-wide distribution of the organism are augmented by STI phenotyping. A compilation of subacute and emergency care data (16) revealed a 45.2% detection rate of solely T. vaginalis from encounters positive for at least one STI. In contrast, a separate determination in an urban emergency care population (18) revealed a 40.7% detection rate of solely T. vaginalis (55.8% for any phenotype incorporating T. vaginalis). It was thus hypothesized that the largely subacute care population analyzed in this study would yield a highly disparate phenotype of detection of solely T. vaginalis. Indeed, Table 1 demonstrates a 54.2% detection rate of solely T. vaginalis from encounters positive for at least one STI (63.5% for any phenotype revealing T. vaginalis). These data further imply T. vaginalis prevalence throughout an entire metropolitan setting; additional TMA-based studies are needed to explore this possibility.

Finally, our findings further demonstrate the value of first-void urine screening. Per STI phenotype, first-void urine was responsible for identification of more organism carriage (19.5%) than other sources (P < 0.0002; Table 1). From an operational standpoint, it was previously reported (21) that urine T. vaginalis screening potentiated detection with efficacy equal to that of genital specimen screening (P ≥ 0.29). Clinically, this translated into a 12.6% urine T. vaginalis detection rate from a subacute care population, compared to 8.9% and 8.6% for cervix and vagina, respectively (P ≤ 0.01). In support of this, Andrea and Chapin (1) reported a urine T. vaginalis detection rate (11.5%) that exceeded those for cervical and vaginal collections (3.2% and 5.2%, respectively). Moreover, analysis of majority African American and Caucasian geographical regions implies an equivalent distribution of T. vaginalis as a result of first-void urine testing (Table 3).

In summary, past relationships of T. vaginalis with human immunodeficiency virus acquisition (4, 8) and transmission (10, 14), deleterious pregnancy outcomes (5), N. gonorrhoeae coinfection (9), and African American race have largely been made using insensitive techniques. Diagnostic approaches almost exclusively involved genital specimens. Our data suggest that TMA-based T. vaginalis screening not only increases detection of the agent but also has the capacity to provide additional insight into geographical and age distributions relative to its detection. TMA-based T. vaginalis analysis, especially involving first-void urine collections, can provide diagnosticians and epidemiologists with a means of deciphering these paradigms of trichomoniasis, with an ultimate goal of enhancing clinical and public health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express sincere appreciation to Deb Hamer and Pam Reiss for expert technical assistance. We also thank Ronald F. Schell for insightful discussions.

Erik Munson, Timothy Kramme, Maureen Napierala, Kimber Munson, and Cheryl Miller have received travel assistance from Gen-Probe, Incorporated.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrea SB, Chapin KC. 2011. Comparison of Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification assay and BD Affirm VPIII for detection of T. vaginalis in symptomatic women: performance parameters and epidemiological implications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:866–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2010. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chernesky M, et al. 2006. High analytical sensitivity and low rates of inhibition may contribute to detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in significantly more women by the APTIMA Combo 2 assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:400–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chesson HW, Blandford JM, Pinkerton SD. 2004. Estimates of the annual number and cost of new HIV infections among women attributable to trichomoniasis in the United States. Sex. Transm. Dis. 31:547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cotch MF, et al. 1997. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. Sex. Transm. Dis. 24:353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaydos CA, et al. 2003. Performance of the APTIMA Combo 2 assay for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in female urine and endocervical swab specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:304–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ginocchio CC, et al. 2012. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2601–2608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guenthner PC, Secor WE, Dezzutti CS. 2005. Trichomonas vaginalis-induced epithelial monolayer disruption and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication: implications for the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Infect. Immun. 73:4155–4160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heine P, McGregor JA. 1993. Trichomonas vaginalis: a reemerging pathogen. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 36:137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hobbs MM, et al. 1999. Trichomonas vaginalis as a cause of urethritis in Malawian men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 26:381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huppert JS, et al. 2005. Use of immunochromatographic assay for rapid detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in vaginal specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:684–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huppert JS, et al. 2010. Adolescent women can perform a point-of-care test for trichomoniasis as accurately as clinicians. Sex. Transm. Infect. 86:514–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ikeda-Dantsuji Y, Konomi I, Nagayama A. 2005. In vitro assessment of the APTIMA Combo 2 assay for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis using highly purified elementary bodies. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:357–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kissinger P, et al. 2009. Trichomonas vaginalis treatment reduces vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Sex. Transm. Dis. 36:11–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller WC, et al. 2005. The prevalence of trichomoniasis in young adults in the United States. Sex. Transm. Dis. 32:593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munson E, Firmani MA. 2009. Molecular diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in the United States. Expert Opin. Med. Diagn. 3:327–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Munson E, et al. 2012. Assessment of screening practices in a subacute clinical setting following introduction of Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification testing. Wis. Med. J. 111:233–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Munson E, et al. 2010. Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification-based analyte-specific reagent and alternative target testing of primary clinical vaginal saline suspensions. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 68:66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Munson E, et al. 2008. Impact of Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification-based analyte-specific-reagent testing in a metropolitan setting of high sexually transmitted disease prevalence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3368–3374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Munson K, et al. 2011. A three-year review of transcription-mediated amplification-based Trichomonas vaginalis male screening in a community of high STI prevalence, abstr C-2128. Abstr. 111th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 21. Napierala M, et al. 2011. Three-year history of transcription-mediated amplification-based Trichomonas vaginalis analyte-specific reagent testing in a subacute care patient population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:4190–4194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nye MB, Schwebke JR, Body BA. 2009. Comparison of APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification to wet mount microscopy, culture, and polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of trichomoniasis in men and women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200:188.e1-188.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schachter J, Chow JM, Howard H, Bolan G, Moncada J. 2006. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis by nucleic acid amplification testing: our evaluation suggests that CDC-recommended approaches for confirmatory testing are ill-advised. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2512–2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwebke JR, et al. 2011. Molecular testing for Trichomonas vaginalis in women: results from a prospective U.S. clinical trial. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:4106–4111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schwebke JR, Hook EW., III 2003. High rates of Trichomonas vaginalis among men attending a sexually transmitted diseases clinic: implications for screening and urethritis management. J. Infect. Dis. 188:465–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sorvillo F, Smith L, Kerndt P, Ash L. 2001. Trichomonas vaginalis, HIV, and African-Americans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:927–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutton M, et al. 2007. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001-2004. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:1319–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr 2004. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 36:6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]