Abstract

Objective

The purpose of our study was to examine the effects of socioeconomic status, acculturative stress, discrimination, and marginalization as predictors of depression in pregnant Hispanic women.

Design

A prospective observational design was used.

Setting

Central and Gulf coast areas of Texas in obstetrical offices.

Participants

A convenience sample of 515 pregnant, low income, low medical risk, and self-identified Hispanic women who were between 22–24 weeks gestation was used to collect data.

Measures

The predictor variables were socioeconomic status, discrimination, acculturative stress, and marginalization. The outcome variable was depression.

Results

Education, frequency of discrimination, age, and Anglo marginality were significant predictors of depressive symptoms in a linear regression model, F (6, 458) = 8.36, P<.0001. Greater frequency of discrimination was the strongest positive predictor of increased depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

It is important that health care providers further understand the impact that age and experiences of discrimination throughout the life course have on depressive symptoms during pregnancy.

Keywords: Depression, Discrimination, Acculturation, Hispanic Women, Pregnancy

Introduction

Depression is a major health concern in Hispanic women during pregnancy and can negatively influence health outcomes of the mother and infant. It has been reported that approximately 20% of all women experience symptoms of depression during pregnancy; and Hispanic women are more likely to experience depression than Hispanic men, or non-Hispanic White or African American women.1,2 These depression-related symptoms may often be disregarded as other hormonal imbalances, often leaving Hispanic women with undiagnosed depression.3 Depression in these women can lead to poor nutrition, substance use or suicidal ideations. Depression can also lead to premature births, low birth weights and developmental delays in the infants.4 It is imperative that we better understand predictors of depression in pregnant Hispanic women so that we can intervene to improve perinatal health outcomes. Hence, the purpose of our study was to examine which demographic and psychosocial factors are the strongest predictors of depression in pregnant Hispanic women.

Background

Depression

Several researchers have found depression to be a common issue among pregnant minority women. Researchers have identified that depression is a mental health disparity that exists among pregnant Hispanic women, and they frequently experience symptoms of depression ranging from moderate to severe symptoms.5,6 In order to contribute to the literature on depression in pregnant Hispanic women, we focused on several possible contributors to depression in this population: acculturation, perceived racial discrimination, acculturation and marginalization, and education.

Acculturation

Acculturation can be defined as the progression in which the attitudes and/or behaviors of people from one culture are altered due to contact with a different culture.7 Acculturation can strongly influence the mental health outcomes of ethnic minorities. Researchers have reported that acculturation has been significantly related to perceived stress, suicidal ideation and higher depression levels in pregnant Hispanic women.8,9 For the purpose of this study, we will build on existing knowledge about the relationship between acculturation and depression in pregnant Hispanic women.

Perceived Racial Discrimination

Racial discrimination is often experienced by Hispanics and can lead to poor mental health. Barksdale and colleagues defined racial discrimination as “overt acts such as verbal slurs, innuendos, or physical action, or less obvious covert acts such as being perceived as less capable, worthy or deserving of success, opportunities or rewards.”10 Discrimination exposes a person to unwarranted mistreatment from others and recurring negative experiences in which they have little control.11 This accumulation of racial discrimination may significantly impact mental health outcomes in the Hispanic population. Researchers have reported that racial discrimination has led to higher depression scores and chronic stress in Hispanic populations.12,13 Since racial discrimination may contribute to depression and stress, there is an emergent need to further explore the relationship between discrimination and depression in pregnant Hispanic women.

Acculturation: Marginalization from Either Anglo or Mexican Cultures

Many researchers are using marginalization as another measure of acculturation and have examined its relationship to stress-related outcomes. For the purposes of this study, marginalization is defined as the experience or process of individuals living within two cultures and having difficulty integrating into one or both of the cultures.14,15 Researchers have identified that marginalization has been significantly related to family conflict, perceived distress, and body dissatisfaction in Hispanic populations.15–17 Investigators have also shown that marginalization has been significantly related to depressive symptoms in various ethnic groups.18 There is a dearth of literature examining this relationship in Hispanic populations.19 Our study contributes to the literature by further examining marginalization and depression among pregnant Hispanic women.

Education

Education can be one measurement of socioeconomic status (SES) that predicts depression in minority populations. Gilman and colleagues found that lower SES was significantly related to higher risk of major depression in adults.20 Bromberger and colleagues reported that depressive symptoms decreased with an increase in education in Hispanic women.21 Comparatively, Lara and colleagues found that, with higher education, Hispanic women had higher depressive symptoms.5 The research shows mixed results on the relationship between SES/education and depression in Hispanic populations. Therefore, we will further explore SES/education and depression among pregnant Hispanic women to clarify the nature of this relationship.

Theoretical Framework

Berry conceptualized a multidimensional process for acculturation.22 As the acculturative process happens, there is the possibility of marginalization. Marginalization may occur when a person has failed attempts in establishing relationships with their own traditional culture or the mainstream culture.22 Marginalization can occur as a result of discriminatory acts or practices from the mainstream culture onto various minority groups.22 The changes accompanying acculturation may become problematic, thereby producing acculturative stress, anxiety or depression.

Berry’s conceptual framework will serve as the theoretical lens for our study. The changes or diversities that accompany acculturation in Hispanic women may increase their risk of depression. During pregnancy, a vulnerable time for mother and infant, it is particularly important to examine the relationships between these factors and depression; thus, our study will examine predictors of depression in Hispanic women. We hypothesize: 1) discrimination, acculturative stress, and marginalization from the Anglo culture will significantly predict depression; 2) women with lower income levels will have higher scores on the depression scale; and 3) as the number of years of education increases depression scores will decrease.

Methods

Sample

Participants were recruited through obstetrical clinics in Austin, and Houston, Texas during 2008 to 2011. Eligible participants were 22–24 weeks gestation when they completed a series of psychosocial surveys. We collected data from participants who were 22–24 weeks gestation because this is a critical window for the development of the neuroendocrine system in the fetus and, any stressors experienced by the mother during this time period may significantly influence fetal development and outcomes.3 Data were collected from 515 pregnant women, who self-identified as Hispanic. Participants completed a form that asked about their age, their highest year of education, and their annual income. Exclusion criteria included pregnant women with fetal anomalies, uterine anomalies, fetal demise, major medical complications, and diagnosed major psychiatric disorders. The study was part of a larger study including biological factors in Hispanic pregnant women.

Survey Instruments

Eligible participants who agreed to be part of the study and who met the study’s eligibility criteria completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),23 Experiences of Discrimination (EOD) scale,24 the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (MASI),25 and the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARSMA).26 The instruments were administered in either English or Spanish depending on the participant’s preferred language. All instruments were translated and back translated and pilot tested prior to administration. All instruments had a coefficient alpha of .75 to .90 in our study, for both English and Spanish.

Depression

Depression severity was measured using the BDI developed by Beck.23 The 21-item depression scale is a multiple choice, self-inventory scale. The scale has been shown to have good reliability; with a Cronbach of .91.27 The BDI is scored by summing the ratings for the 21 items. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The maximum total score is 63. Questions of the BDI assess the typical symptoms of depression such as pessimism, suicide, irritability, insomnia, fatigue, and changes in appetite.27

Discrimination

The frequency of experiences of discrimination was measured using the EOD scale.24 The measurement asks participants whether or not they have ever experienced discrimination in nine identified situations, as well as unfair treatment they believe they may have experienced because of their race or ethnicity. Krieger and associates found the EOD scale to be both valid and reliable among a Latino sample, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74.28 We assigned the value of 0 to reports of no discrimination, 1 to 1 report, 2.5 to 2–3 reports and 5 to reports of 4 or more. The assigned values were summed for a total EOD frequency. A higher score indicated a higher frequency of EOD/unfair treatment because of ethnicity.

Acculturative Stress

Acculturative stress was measured using the 36-item MASI.25 The goal of this instrument is to measure stress among persons of Mexican origin living in the United States. Four subscales are included in the MASI: English Competency Pressures, Spanish Competency Pressures, Acculturative Stress, and Pressure against Acculturation. Respondents rated each item on a five-point scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. For the purposes of our study, we used the subscale Pressure against Acculturation. Acculturative stress was scored using 11 items from the 36-item MASI scale. Each item was scored on a six-point scale, 0–6. Zero indicated the item “does not apply,” 1 that the item is “not stressful at all,” and a 5 indicated the item is “extremely stressful.”. The items were summed and the total was the pressure to acculturate score. A high score indicates greater pressure to acculturate.

Marginalization

The ARSMA is multifactorial and different types of acculturation can be measured in the ARSMA such as marginality.26 Marginality provided information about the exclusion from cultural groups. The marginalization scales are calculated using the 18-item ARSMA-II Scale II. Six questions assess Anglo marginalization such as: “I have difficulty accepting some ideas held by Anglos.” Six questions assess Mexican marginalization such as: “I have difficulty accepting ideas held by some Mexicans.” Six questions assess Mexican American marginalization such as “I have difficulty accepting some values held by Mexican Americans.” Each question is scored on a 5-point scale with values 1 through 5. A score of 1 indicates the item does not apply “not at all,” a score of 2 indicates the item applies “very little or not very often” and a score of 5 indicates the item occurs or applies “Extremely often or almost always.” The items are summed and the total is the respondent’s score on that marginality scale. As such, the range for each scale is 6–30. A high score indicates being highly marginalized (or feeling highly marginalized).26 To be Anglo marginalized means to have difficulty accepting Anglos, their beliefs, practices, and/or behaviors; Mexican marginalized means to have difficulty accepting beliefs, practices and/or behaviors of Mexicans.

Design and Analysis

A prospective observational design was used. Analyses were done using SAS 9.3. Pearson’s correlations were analyzed to examine multicollinearity. Linear regression analyses were conducted to determine predictors of depression. We assessed the extent of missing data prior to constructing our final linear regression model and imputed missing data using the SAS PROC MI procedure, which is considered an optimal treatment of missing data.29 We imputed 20 data sets, which were analyzed separately. Parameters and standard errors were then combined to obtain aggregate estimates that are used for inferential tests.30

Results

Demographics are presented in Table 1. The participants in our sample range in age from 14 to 43 years with an average age of 24.6 years. Many participants were of lower socioeconomic status, with nearly half the participants (44%) making <$25,000 annually, and a third (34.3%) with less than a high school education. The majority of our sample identified as Mexican or Mexican American.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | na (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean years) | 24.61 |

| 14–17 | 54 (10.6%) |

| 18–25 | 257 (50%) |

| 26–43 | 214 (39.4%) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 275 (53.6%) |

| Married | 236 (46.4%) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 179 (34.9%) |

| High school or more | 334 (65.1%) |

| Income (mean $) | $27,526.98 |

| Less than $25K | 225 (44.1%) |

| $25K or more | 287 (55.9%) |

| Country of birth | |

| US-born | 298 (58.1%) |

| Foreign-born | 215(41.9%) |

| Number of years in US (mean years) | 20.41 |

| 0–10 years | 51 (10.0%) |

| 11 or more years | 462 (90.0%) |

| Generational status | |

| First generation | 167 (32.5%) |

| Second generation | 172 (33.5%) |

| Third or higher generation | 175(34.1%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Mexican American | 293(57.1%) |

| Mexican | 144 (28.1%) |

| Puerto Rican | 1(0.2%) |

| Hispanic | 72(14.2%) |

| Other | 2(0.4%) |

| EOD frequency (mean) | 4.91 |

| BDI total level (mean) | 10.57 |

| Pressure to acculturate (MASI, mean) | 6.35 |

| Total N | 514 |

The n values for country of birth, age, marital status, number of years in U.S. and ethnicity are not equal due to missing data. Ten of the participants chose not to answer all of the questions in the questionnaire, which accounted for the unequal n values.

We fit a regression model using EOD frequency, acculturative stress, Anglo marginality, Mexican marginality, Mexican American marginality, age, and SES variables (income and education) as predictors of depression (BDI). Prior to fitting the model, we visually inspected the distribution of the dependent variable and, due to a moderate positive skew, we transformed it with a natural log. We assessed the linearity of independent variables by fitting quadratic models for each variable individually. Log transformations were used to transform the education, EOD, and the pressure to acculturate variables to linearize the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.31 Because the log-transformed education variable was still curvilinear after the log transformation, we fit a polynomial education effect by first mean centering the variable to reduce collinearity with the quadratic term, and then squared the variable to form the quadratic value. We divided income by 1000 to aid interpretation of coefficients. We assessed multicollinearity of all variables in the model using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The largest VIF that we observed was 2.45 for Mexican American marginality, which was well below the recommended cutoff of 10.31

After fitting models, we assessed the normality of residuals using quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots and assessed the homogeneity of variance by plotting fitted values and residuals in a scatter-plot. The Q-Q plots adhered to a straight line and the fitted values by residuals scatterplot showed that there was no relationship between the fitted values and residuals indicating homogeneity of variance of the residuals. We examined the number of cases that were missing under listwise deletion in ordinary least squares regression and determined that 43 cases would be excluded due to missing data for at least one of the variables in the model. Post hoc power for the entire model, assuming a two-tailed alpha of .05 is > .99; R-Squared = .10. The results of this model are displayed in Table 2. (R-squared is not available for models from multiply imputed data and we therefore used the model with listwise deletion.)

Table 2.

Regression model for predictors of depression N = 515a

| Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Degrees of Freedom | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.2571 | 0.1625 | 13.89 | 502 | <.0001 |

| Age | −0.0165 | 0.0057 | −2.88 | 501 | .004 |

| Education log | −0.0162 | 0.1598 | −0.10 | 494 | .920 |

| (Education log)2 | −0.7882 | 0.3724 | −2.12 | 499 | .035 |

| Income | −0.0007 | 0.0014 | −0.48 | 452 | .631 |

| Experiences of discrimination | 0.1657 | 0.0305 | 5.44 | 502 | <.0001 |

| Pressure to acculturate | 0.0019 | 0.0317 | 0.06 | 500 | .952 |

| Anglo marginality | 0.0261 | 0.0073 | 3.56 | 503 | <.0001 |

| Mexican American marginality | −0.0091 | 0.0117 | −0.78 | 503 | .435 |

| Mexican marginality | 0.0020 | 0.0112 | 0.18 | 503 | .859 |

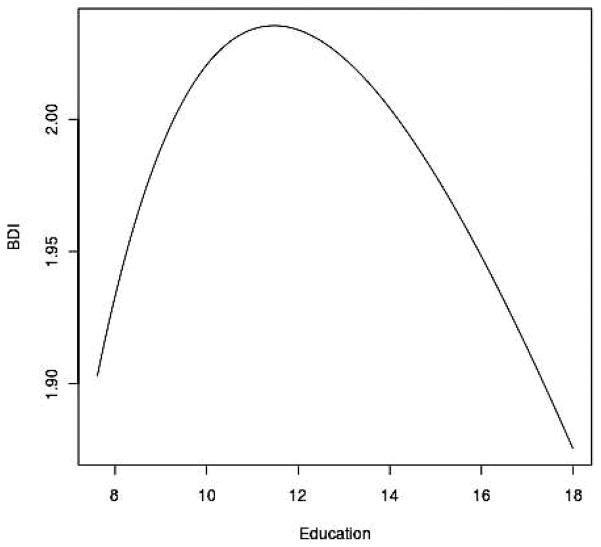

Figure 1 illustrates the curvilinear nature of the relationship between education (measured in number of years) and BDI (measured in units) scores and demonstrates that BDI increases when the numbers of years of education are 10–12; however, BDI totals decrease after 12 years of education.

Fig. 1.

BDI is values are the logged value of the participants’ total BDI score. Education values are the number of years of education the participants had completed.

Age, EOD frequency, and Anglo marginalization were significant predictors of depression in the model. In the regression model, age exhibited a significant negative relationship with BDI (t (501) = −2.88, P = .004), EOD frequency exhibited a significant positive relationship with BDI (t (502) = 5.44, P <.001), and Anglo marginalization exhibited a significant positive relationship with BDI (t (503) = 3.56, P <.001) and as such were significant predictors of depression in the model. The quadratic education parameter was significant (t (499) = −2.12, P = .035), though the linear component was not (t (494) = −0.10, P = .920), indicating a curvilinear relationship between education and BDI. The relationship is displayed in fitted values in Figure 1, which demonstrates that BDI increases until approximately 12 years of education, then decreases. We show that the relationship between age and depression is negative. There was not a significant relationship between income (t (452) = −0.48, P = .631), pressure to acculturate (t (500) = 0.06, P = .952), Mexican American marginality (t (503) = −0.78, p = .435), and Mexican marginality (t (503) = 0.18, P = .859). Discrimination, Anglo marginality and education had the overall greatest impact on depression in this model.

Discussion

We found support for our first hypothesis; discrimination and marginalization from Anglo culture were predictors of depression. We did not find confirmation that acculturative stress predicted depression in the pregnant Hispanic women in our sample. We also did not find evidence for our second hypothesis, as the relationship between income and BDI score was not statistically significant. We did find support for our third hypothesis; education was a significant predictor of BDI in this model. The findings of our study are consistent with previous research that among Hispanic–origin adults that found that discrimination was a significant predictor of depression even after taking into account age, education level, and acculturation.13 We found that age, education, discrimination, and Anglo marginality were significant predictors of depression in the pregnant Hispanic women in our sample; with discrimination being the strongest predictor. Depression displayed an inverse relationship with age. As age increased, depression scores decreased. These findings highlight the importance of discrimination as a societal stressor that contributes to depression in these women.

We speculate that those who were younger and with less education, possibly had fewer resources, which could have led to more stress and depression.20 Higher education levels predicted lower levels of depression in this sample, showing that obtaining higher education may in fact be protective of depression in pregnant Hispanic women.

We also speculate that if the women felt they were marginalized from Anglo culture they may have struggled with feeling ostracized and not belonging to the mainstream culture, and thus this contributed to the increased stress and depression. We posit that when one is attempting to fit in with Anglo mainstream society this can create stress in everyday societal interactions thereby increasing risk for depression. It is consistent with the literature that the experiences of Anglo marginalization can lead to poor mental health outcomes in various minority groups.17,18

We did not find that income, Mexican marginality, or acculturative stress, were significant predictors of depression in our population. We posit that women with lower income may have had other resources; therefore, they may not have been experiencing depression related to lack of resources. Furthermore, this sample may not have perceived being marginalized from Mexican culture as a stressor; therefore it was not related to depression. Acculturative stress may not have been a significant enough stressor in this sample to lead to depression.

Study Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. The data were based on self-report, which could have presented bias or inaccurate recollection of previous events. Acculturation has limited variation because the sample is limited to Hispanic women living in Texas. There may likely be more significant predictor variables than the ones we examined. We suggest future studies examining other predictors that may impact depression among pregnant Hispanic women.

Despite the limitations, our study contributes to the literature by providing data on the effects of discrimination and acculturation on mental health outcomes in pregnant Hispanic women. With increased knowledge surrounding causes of depression in Hispanic women, health care providers can focus their efforts on preventative interventions and advanced treatments individualized for this population. Depression during pregnancy can lead to poor perinatal outcomes.3 In gaining further knowledge about these factors, we can prevent the onset of health disparities such as depression in pregnant Hispanic women.

Furthermore, we need to gain understanding of various ways to treat depression in pregnant women. The treatment options for depression in pregnant women are complex and can have adverse effects on the mother and infant.31 Patel and Windsor found that treatment options and availability for depression care are often scarce for pregnant women.32 Further work is needed to understand culturally appropriate and effective treatment options for pregnant Hispanic women.

We also reported in our study that younger age was related to higher depression scores. Hispanic adolescents who are pregnant are a vulnerable population and depression may contribute to poor perinatal health outcomes in this population.33,34 Further work is needed to understand the predictors, risks, and prevalence of depression among adolescent pregnant Hispanic women.

Depression is one health disparity affecting minority populations, and especially women of Mexican origin, at alarming rates; it can be disabling and leave lasting effects. If we learn more about different risks factors and how they contribute to depression and other health disparities in minority populations, we can begin to develop ways to eliminate these factors, thereby decreasing the health disparity gap among minority populations.

Acknowledgments

NIH R01NR007891 supported this work: R. J. Ruiz (PI).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Design and concept of study: Walker, Ruiz

Acquisition of data: Walker, Ruiz

Data analysis and interpretation: Walker, Ruiz, Chinn, Marti, Ricks

Manuscript draft: Walker, Ruiz, Chinn, Marti, Ricks

Statistical expertise: Marti, Ricks

Acquisition of funding: Ruiz

Administrative: Walker, Ricks

Supervision: Ruiz

References

- 1.Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FA, Barry KL. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetric settings. J Women Health. 2003;12(4):373–380. doi: 10.1089/154099903765448880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The American Pregnancy Association. [Accessed April 2012.];Depression During Pregnancy. http://www.americanpregnancy.org/pregnancyhealth/depressionduringpregnancy.html.

- 4.Ruiz RJ, Marti CN, Pickler R, Murphey C, Wommack J, Brown CE. Acculturation, depressive symptoms, estriol, progesterone, and preterm birth in Hispanic women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0258-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lara MA, Le HN, Letechipia G, Hochhausen G. Prenatal depression in Latinas in the U.S. and Mexico. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(4):567–576. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davila M, McFall SL, Cheng D. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum Latinas. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(3):318–325. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslow L, editor. Encyclopedia of Public Health. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz J, Dolbier C, Fleschler R. The relationships among acculturation, biobehavioral risk, stress, corticotrophin-releasing hormone, and poor birth outcomes in Hispanic women. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):926–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hovey JD, King CA. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(9):1183–9216. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barksdale DJ, Farrug ER, Harkness K. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: Perceptions, emotions, and behaviors of black American adults. Issues Ment HealthNurs. 2008;30(2):104–11. doi: 10.1080/01612840802597879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belle Doucet DJ. Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. women. Psychol Women Q. 2003;27(2):101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(3):295–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, et al. Perceived discrimination, perceived stress, and mental and physical health among Mexican origin adults. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2008;30:401–424. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber CE, Vega LD. Conflict, cultural marginalization, and personal costs of filial caregiving. J Cult Divers. 2011;18(1):20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren CS, Castillo LG, Gleaves DH. An evaluation of the sociocultural model of eating disorders in Mexican-American women: Behavioral acculturation and attitudinal marginalization as moderators. Eat Disord. 2010;18(1):43–57. doi: 10.1080/10640260903439532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castillo LG, Cano M, Chen SW, et al. Family conflict and intragroup marginalization as predictors of acculturative stress in Latino college students. Int J Stress Manag. 2008;15(1):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo L, Conoley C, Brossart D. Acculturation, White marginalization, and family support as predictors of perceived distress in Mexican American female college students. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51(2):151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu-Rayya HM. Acculturation and well-being among Arab-European mixed-ethnic adolescents in Israel. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(5):745–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H. Multidimensional acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms in Korean Americans. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(2):98–103. doi: 10.1080/01612840802597663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status in In childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):359–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bromberger JT, Harlow S, Avis N, Kravitz HM, Cordal A. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: The study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN) Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1378–1385. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 163–185. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT. Depression: Courses and Treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1967. pp. 333–335. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: Risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90307-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez N, Meyers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, Garcia-Hernandez L. Development of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14(4):451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II. A revision of the original ARSMA. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Neter J, Li W. Applied Linear Statistical Models. 5. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SR, Wisner KL. Decision making for depression treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(7):589–595. doi: 10.1002/da.20844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodman JH, Tyer-Viola L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Women Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(3):477–490. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. [Accessed April 25, 2012.];US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/teenagepregnancy.html.