Abstract

Recently, we reported a unique influenza A virus subtype H17N10 from little yellow-shouldered bats. Its neuraminidase (NA) gene encodes a protein that appears to be highly divergent from all known influenza NAs and was assigned as a new subtype N10. To provide structural and functional insights on the bat H17N10 virus, X-ray structures were determined for N10 NA proteins from influenza A viruses A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/164/2009 (GU09-164) in two crystal forms at 1.95 Å and 2.5 Å resolution and A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/060/2010 (GU10-060) at 2.0 Å. The overall N10 structures are similar to each other and to other known influenza NA structures, with a single highly conserved calcium binding site in each monomer. However, the region corresponding to the highly conserved active site of influenza A N1-N9 NA subtypes and influenza B NA differs substantially. In particular, most of the amino acid residues required for NA activity are substituted, and the putative active site is much wider because of displacement of the 150-loop and 430-loop. These structural features and the fact that the recombinant N10 protein exhibits no, or extremely low, NA activity suggest that it may have a different function than the NA proteins of other influenza viruses. Accordingly, we propose that the N10 protein be termed an NA-like protein until its function is elucidated.

Keywords: enzyme, mechanism, receptor, glycoprotein, infection

Influenza viruses cause severe respiratory illness and death. Of the three types of influenza virus, type A infects a wide range of avian and mammalian species and is the major cause of annual epidemics and occasional pandemics. Influenza A viruses can be classified into subtypes based on the antigenic properties of their surface glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Sixteen subtypes of HA (H1 to H16) and nine of NA (N1 to N9) were known to circulate in avian and mammalian species. Recently, we reported the discovery of a genetically distinct influenza A virus H17N10 from bats, offering exciting opportunities to study an influenza virus from a different evolutionary background (1).

Influenza virus NA, also called sialidase, is one of the two influenza surface glycoproteins and catalyzes the cleavage of glycosidic linkages between terminal sialic acid and adjacent sugar residues of glycoproteins and glycolipids. This activity is essential for virus infection and transmission. The well-documented influenza virus infection cycle starts with the attachment of virus through the HA glycoprotein to sialic acid-containing glycan receptors on the host cell surface. The virus is then internalized and, after fusion of the viral envelope to the endosomal membrane, viral RNAs are translocated into the cell nucleus, transcribed, and replicated to direct the production of new viral components. The NA is critically important during the final stages of infection, where it cleaves off sialic acid from glycans on the target host cell, as well as from newly formed budding virions, thus preventing virus aggregation and facilitating progeny release from the host cell. Based on their sequences, influenza A NAs from avian and mammalian species, except bats, can be divided into two groups: group 1 (N1, N4, N5, and N8) and group 2 (N2, N3, N6, N7, and N9) (2). Crystal structures have been published for two group 2 NAs [N2 (3) and N9 (4)], and all group 1 NAs [N1 (5, 6), N4 (5), N5 (7), and N8 (5)], as well as influenza B NA (8). The published type A and B NA structures have a similar topology, despite having up to 75% difference in amino acid sequence and all share a highly conserved active site replete with charged residues (8–10).

The recently identified bat H17N10 virus genome has raised considerable interest in the origin and evolution of influenza viruses. Although the H17 HA shares considerable amino acid sequence identity with the other 16 HA subtypes, the NA-like (NAL) protein encoded by the N10 genes shows extensive divergence from known influenza NAs, particularly with respect to the canonical NA active site residues (1). The overall sequence identities are as low as 20–27% between N10 NAL and other influenza A NAs, compared with 40–67% identity among influenza A NAs (1). To provide insights into the structure and function of the unique N10 NAL, we expressed NAL proteins from two H17N10 bat influenza viruses, A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/164/2009 (GU09-164) and A/little yellow-shouldered bat/Guatemala/060/2010 (GU10-060), in a baculovirus system using Hi5 cells. Crystal structures of GU09-164 (crystal form 1) and GU10-060 NALs were then determined to 1.95 Å and 2.0 Å, respectively. In addition, we determined the structure of GU09-164 NAL in another crystal form 2 at 2.5 Å that differs mainly in the 150- and 430-loops, which are constrained differently compared with crystal form 1 (SI Materials and Methods, SI Results, and Fig. S1). The overall structure of N10 NAL is similar to other influenza A and B NAs. However, the N10 NAL has a highly diverged putative active site with a much wider pocket and substitution of the canonical active site residues that are associated with NA activity.

Results

Overall Structure of the GU09-164 NAL.

The ectodomain (residues 82–460 in N2 numbering) of GU09-164 NAL was overexpressed as a tetramer in a baculovirus expression system (11) (for details see Materials and Methods). The purified protein was crystallized in crystal form 1 and its structure determined to 1.95 Å resolution (Table 1) with good electron density for all residues, including the active site 150-loop, which is flexible in some uncomplexed NA structures (11). The GU09-164 NAL structure is a typical “box-shaped” tetrameric association of identical monomers, containing six four-stranded, antiparallel β-sheets that form a propeller-like arrangement (Fig. 1A), as previously described for influenza A subtypes N1, N2, N4, N5, N8, and N9 (3–5, 7, 11), and influenza B virus NA (8). Comparison of the GU09-164 NAL monomer with other NAs reveals surprising similarity despite low sequence identity (1) (Fig. S2). Superimposition of GU09-164 NAL with group 1 N1 (PDB ID code 3BEQ) (11), N4 (PDB ID code 2HTV) (5), N5 (PDB ID code 3SAL) (7), and N8 (PDB ID code 3O9J) NAs (12), as well as group 2 NAs [N2 (PDB ID code 1NN2) (13) and N9 (PDB ID code 3NN9) (14)] results in rmsds of 1.6–1.8 Å (for Cα atoms), which are remarkably similar to rmsds of around 1.6 Å between N1 and N2 or N9 NAs (11). On the other hand, superimposition with flu B NA (PDB ID code 1NSB) (8) gave a slightly higher rmsd of 2.0 Å. Seven interchain disulfide bonds (C124-C129, C183-C230, C232-C237, C280-C289, C318-C337, C92-C417, C421-C447) in the ectodomain of GU09-164 NAL are fully conserved with known influenza NA proteins (3, 8); however, one conserved interchain disulfide (C278-C291) is absent in GU09-164 NAL due to S278 and G291 substitutions (Table S1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics of GU09-164 and GU10-060 NAL crystals

| Dataset | GU09-164 (crystal form 1) | GU10-060 |

| Space group | I4 | P41212 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = b = 176.3, c = 193.3 | a = b = 107.9, c = 345.2 |

| Resolution (Å)* | 50.0–1.95 (1.98–1.95) | 50.0–2.00 (2.03–2.00) |

| X-ray source | SSRL 11–1 | APS 23ID-D |

| Unique reflections | 210,731 | 135,663 |

| Redundancy* | 2.6 (2.5) | 3.9 (3.4) |

| Average I/σ(I)* | 23.1 (1.5) | 18.8 (1.7) |

| Completeness* | 98.8 (99.5) | 98.0 (86.8) |

| Rsym† | 0.06 (0.89) | 0.10 (0.67) |

| Monomers in arbitrary units | 6 | 4 |

| Vm (Å3/Da) | 2.9 | 3.4 |

| Reflections used in refinement | 210,560 | 135,354 |

| Refined residues | 2,202 | 1,266 |

| Refined waters | 1,408 | 738 |

| Rcryst‡ | 0.180 | 0.189 |

| Rfree§ | 0.223 | 0.226 |

| B values (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 36.5 | 37.2 |

| Waters | 42.0 | 41.7 |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 41.7 | 43.1 |

| Ramachandran plot (%)¶ | 96.4, 0.1 | 96.3, 0.1 |

| rmsd bond (Å) | 0.009 | 0.013 |

| rmsd angle (deg.) | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| PDB ID codes | 4GDI | 4GDJ |

*Parentheses denote outer-shell statistics.

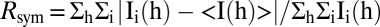

† , where <I(h)> is the average intensity of i symmetry-related observations of reflections with Bragg index h.

, where <I(h)> is the average intensity of i symmetry-related observations of reflections with Bragg index h.

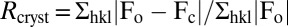

‡ , where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors.

, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors.

§Rfree was calculated as for Rcryst, but on 5% of data excluded before refinement.

¶The values are percentage of residues in the favored and outliers regions analyzed by MolProbity (36).

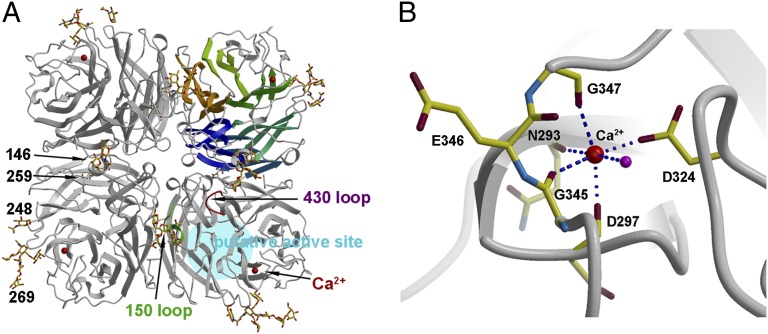

Fig. 1.

Overall structure of GU09-164 N10 NAL with a conserved calcium binding site. (A) The NAL tetramer is viewed from above the viral surface and consists of four identical monomers in C4 symmetry. One monomer is represented in six different colors to illustrate the canonical β-propeller-fold of six four-stranded, antiparallel β-sheets. The active site region in influenza A and B NAs is highlighted in blue and designated here as the NAL putative active site as no activity has yet been found. This region is located on the membrane-distal surface (on top of the molecule). The putative active site 150-loop and 430-loop are highlighted, and four N-linked glycosylation sites are shown with attached carbohydrates. A single bound calcium ion is shown in red spheres. (B) A close-up view of the conserved calcium binding site in each NAL monomer. The calcium ion (large red sphere) is coordinated by Asn293, Asp297, Gly345, Asp324, and Gly347, and a water molecule (smaller magenta sphere).

In addition, one calcium ion binding site, which is conserved in all known flu A and flu B NAs (7), was observed in GU09-164 NAL (Fig. 1). This Ca2+ site is formed by the four backbone carbonyl oxygens of Asn293, Asp297, Gly345, and Gly347, a carboxyl oxygen from Asp324, as well as a water molecule. Calcium ions have been shown to be critical for the thermostability and activity of influenza virus NAs (15, 16), and this conserved metal site was proposed to be important in stabilizing a reactive conformation of the active site by otherwise flexible loops (17).

Taken together, although sequence similarity between GU09-164 NAL and other known influenza NAs is low, the similar overall structure and the conserved calcium site of GU09-164 establishes its structural relationship to other influenza NA subtypes.

Putative Active Site of GU09-164 NAL.

The active site of influenza NA is located on the membrane-distal surface (Fig. 1A). However, relative to influenza virus NA, GU09-164 NAL has dramatic changes in the normally highly conserved active site residues in influenza A and B subtypes, including eight charged or polar residues (Arg118, Asp151, Arg152, Arg224, Glu276, Arg292, Arg371, and Tyr406) (8). In GU09-164 NAL, only Arg118, Arg224, and Glu276 are conserved (Fig. 2A and Table S1). Arg292 and Arg371 are replaced by Thr and Gln, respectively, and Thr292 is not even accessible on the putative active site surface. Together with Tyr406, which is replaced by Arg406 in GU09-164 NAL, Arg118, Arg292, and Arg371 are believed to be critical for the first binding step on the NA catalytic pathway by forming charge–charge interactions with the carboxylate group of sialic acid (18–20). In addition, the NA active site architecture is stabilized by a constellation of largely conserved, second-shell residues in influenza A and B viruses (Glu119, Arg156, Trp178, Ser179, Asp/Asn-198, Ile222, Glu227, His274, Gly277, Asn294, and Glu425) (8, 11). In GU09-164 NAL, only 3 of these 11 residues are conserved: Ser179, Asp198, and Glu425 (Fig. 2A). Asp151, Arg152, and Glu277, which are all believed to contribute to stability of the cationic intermediate, are replaced by Trp151, Glu152, and Tyr277. These dramatic changes of conserved active-site residues suggest that the function of GU09-16 has diverged from influenza A and B virus NAs, which cleave sialic acid moieties from host glycan receptors.

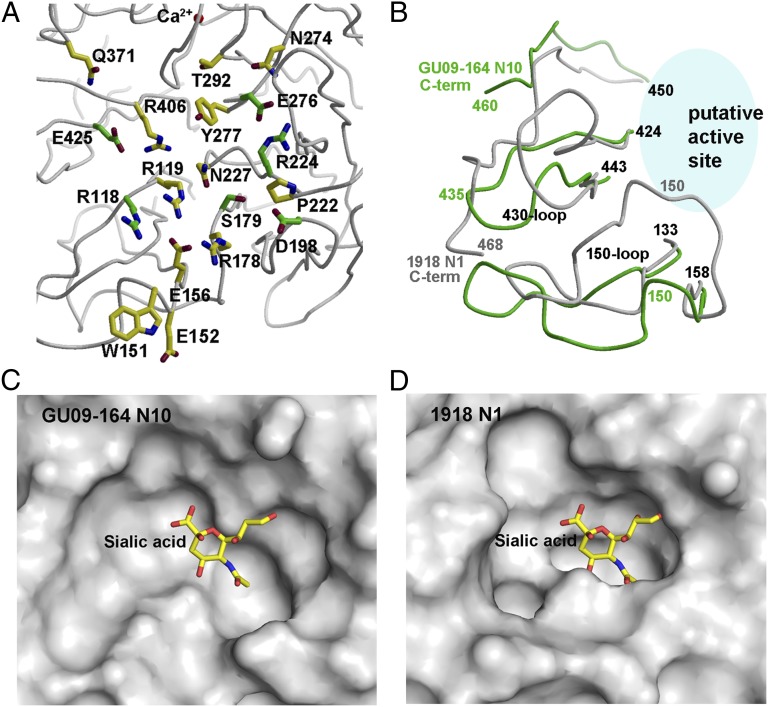

Fig. 2.

Putative active site of GU09-164 N10 NAL and comparison with the active site of 1918 N1 NA. (A) Conserved catalytic and active site residues in other known NAs are shown on GU09-164 NAL putative active site. The six residues that are conserved in NA and NAL are colored with green carbon atoms, whereas the 11 active site residues that are not conserved are colored with yellow carbon atoms. (B) Comparison of GU09-164 NAL 150-loop, 430-loop, and C terminus (in green) with that of the corresponding loops in 1918 NA (in gray). GU09-164 NAL C terminus is 10-residues shorter than that 1918 NA [two residues are absent in the 1918 NA model (PDB ID code 3BEQ)]. The 150-loop and 430-loop of GU09-164 NAL adopt a more open conformation than 1918 NA. (C) Molecular surface of the putative active site of GU09-164 NAL. A “canonical” sialic acid is modeled into the NAL structure as observed in NA structures. Its glycerol moiety in this mode of sialic acid binding would collide with the NAL active site. However, the putative active site pocket of GU09-164 NAL is much wider than 1918 NA, as shown in D. Thus, the putative active site does not seem to be configured for conventional sialic acid binding and a ligand, if any, is currently unknown. (D) Molecular surface of the active site of 1918 NA in its apo form with the 150-loop in the open conformation. A canonical sialic acid model in other NA structures is superimposed to show its location. For comparison, all panels are generated in the same orientation.

In addition, the putative active site pocket of GU09-164 NAL is much wider than those of influenza A and B NAs (Fig. 2 B, C, and D). We selected the high resolution structure (1.64 Å) of the 1918 N1 NA in its apo form with an open active site configuration (Fig. 2D) for structural comparison (11) because of its more extended 150 cavity due to an altered disposition of the 150-loop (5, 7, 11). The overall structures of GU09-164 NAL and 1918 NA are very similar (Fig. S2A), but large conformational differences arise in the 150-loop and 430-loop, as well as in the C terminus (Fig. 2B). Significantly, in GU09-164 NAL, the 150-loop has a 3-aa deletion compared with N1 and N2 NAs, and the 430-loop is three and four residues shorter than in N1 and N2 NAs, respectively (Table S1). Furthermore, the C terminus is truncated by 9- or 10-residues compared with N2 or N1 NAs (Table S1), allowing the 430-loop of GU09-164 NAL to shift away from the pocket toward the location of the C terminus of 1918 NA, where NAL residue 435 moves about 9 Å to now superimpose with 1918 NA residues 465–466 (Fig. 2B). The 150-loop also moves away from the active site pocket with residue 150 being displaced by about 8 Å (Fig. 2B). In GU09-164 NAL, the 150-loop is displaced from the putative active site such that Leu145 to Ser148 contact the neighboring monomer in the biological tetramer, and enable hydrogen bonds to be formed between Asn146 and Glu109′ and between Ser148 and Pro105′ (Fig. 1A), in an interaction not observed in other flu A or flu B NA structures (3–5, 7, 8, 11). Because of these conformational differences, GU09-164 NAL and 1918 NA have different shaped active site pockets (Fig. 2 C and D). A canonical sialic acid molecule from other flu A and B NA structures (11) would clash with the bottom of the GU09-164 NAL putative active site (Fig. 2C), which is also much wider than that of 1918 NA (Fig. 2D).

Glycosylation of GU09-164 NAL.

GU09-164 NAL has five potential N-linked glycosylation sites in the stalk region and four in the head at Asn146, Asn248, Asn259, and Asn269 (Fig. 1A and Table S1). All four sites in the head appear to be posttranslationally modified, as indicated from additional electron density for attached oligosaccharides at these positions. The Asn146 site is on the membrane-distal surface, close to the active site, and is the only conserved glycosylation site in other flu A and flu B NAs (3, 5, 19). Asn248 is also on the top surface of the monomer and close to the putative active site, whereas Asn269 is on the side face, and Asn259 is on the bottom surface of the monomer close to the tetramer interface. The carbohydrate at Asn259, as well as the potential glycosylation sites in the stalk, might play an important role in protecting the stalk from proteolytic cleavage.

Comparison of the Crystal Structure of GU10-060 NAL with GU09-164 NAL.

The ectodomain (82-460) of GU10-060 NAL was overexpressed in a baculovirus system and its crystal structure was determined to 2.0 Å resolution. Interestingly, even with essentially the same construct as GU09-164 NAL and the same expression and purification conditions, the ectodomain of GU10-060 NAL is largely monomeric in solution and in the crystal, whereas the ectodomain plus stalk region behaves as a tetramer. Nevertheless, the overall GU10-060 NAL monomer structure is very similar to GU09-164 NAL, with an rmsd value of 0.7 Å except for three flexible loops, the 110, 150, and 430 loops, which are largely disordered in the GU10-060 NAL crystal (Fig. 3). Eighteen residues differ between the two N10 NALs, with 13 in the ectodomain (Table S1), but the effects are local (Fig. 3). The putative active site pocket residues are exactly the same in the two N10s (Fig. 3), and most side chains adopt the same conformation, indicating similar function. Similar to GU09-164 NAL, one conserved Ca2+ site and the same four N-linked glycosylation sites are found in each GU10-060 NAL monomer.

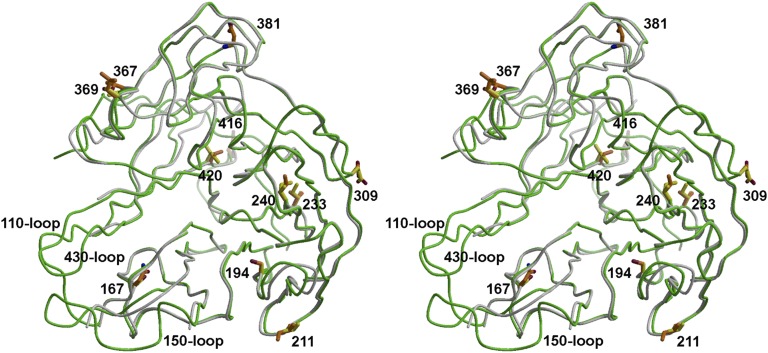

Fig. 3.

Stereoview of the superimposed monomeric GU10-060 NAL (in gray) with a monomer from the GU09-164 NAL tetramer (in green) in ribbon presentation. Three loops of GU10-060 NAL including the 110-loop (from 103 to 110), 150-loop (from 141 to 151), and 430-loop (from 428 to 439), as well as an N-terminal fragment (82–90) and a C-terminal fragment (455–460) are not modeled because of poor electron density. The side chains of NAL residues that differ in sequence are shown with yellow carbons for GU09-164 and brown carbons for GU10-060. None of the changes are in the putative active site region.

Superimposition of GU10-060 NAL monomer onto GU09-164 NAL tetramer shows that one of the substitutions, V211I (from GU09-164 to GU10-060) (Fig. 3) is in the tetramer interface, whereas four other changes, S167N, A194S, G416E, and I420V (Fig. 3 and Table S1) would be close to the tetramer interface, if GU10-060 NAL also forms a tetramer on the viral surface. The functional role of these mutations in tetramer formation or in other protein activities needs further study.

Evaluation of the Neuraminidase Activities of GU09-164 NAL and GU10-060 NAL.

The ectodomain plus stalk region (37-460) of GU09-164 and GU10-060 NALs were overexpressed in a baculovirus expression system. Significantly, no sialic acid cleavage activity of GU10-060 NAL was observable with the commonly used substrate 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (4-MU-NANA), using several protein preparations and following the same NA expression, purification, and activity measurement protocols that were successfully used in 10 different human and swine NAs, including strains from the 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009 human pandemic, and some swine-origin HA or NA progenitors of 2009 pandemic viruses, which had a wide range of NA activities (21). Extremely weak NA activity was detected with some, but not all, batches of GU09-164 NAL protein preparation from Hi5 insect cell cultures, but only when the protein concentration was around 0.1 mg/mL. A kcat value was estimated and found to be 1,000- to 10,000-fold lower than that of the weakest swine or human NAs reported (21). Extremely weak NA activity was also observed for N10 NAL when expressed as a recombinant protein of the N10 NAL ectodomain fused to a vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein tetramerization domain (SI Materials and Methods, SI Results, and Fig. S3). In addition, we tested the N10 NALs against natural sialosides using a recently reported glycan microarray assay (21), and again no activity was detected. Thus, we conclude that the N10 NAL protein does not have a biologically relevant sialidase activity and it remains to be determined what its function is.

Discussion

In influenza virus infection, the two surface glycoproteins, HA and NA, mediate interactions of the virus with sialic-acid containing host cell receptors. HA binds to sialylated glycan receptors to mediate virus entry, but NA removes the sialic acid from the same receptors, as well as from its own surface, to facilitate progeny virus release. In the absence of NA activity, HA binds to sialic acids on virion surface glycoproteins leading to virus clumping. NA has therefore become an important therapeutic target with four approved NA-inhibitor antiviral drugs (22–25). The recently identified bat influenza viruses encode two proteins that resemble the HA and NA of other influenza viruses, but their structure and function are unknown (1). Here we structurally and functionally investigate the bat “NA” protein, which was previously assigned as a unique subtype N10.

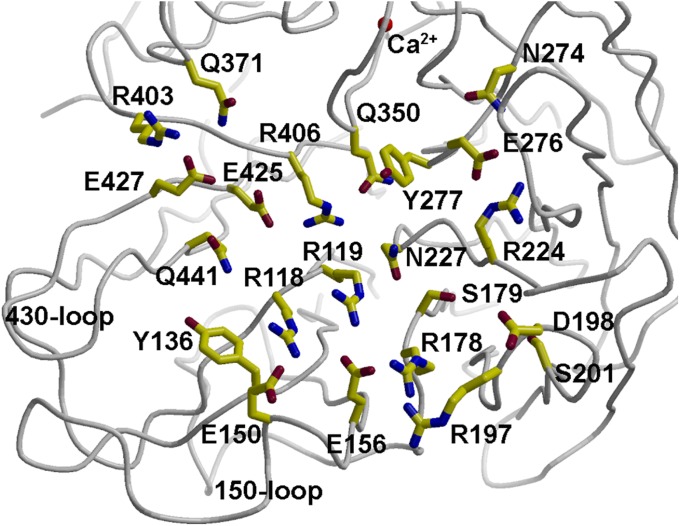

Structural studies of influenza virus A and B NAs have previously revealed a well-conserved overall structure with an active site lined by a constellation of totally conserved amino acids (9, 10). Here we show that crystal structures of two N10 NA proteins from bat influenza viruses are superimposable on other influenza NAs, with conservation of a calcium binding site, indicating that the bat N10 NA is an NAL protein in overall structure. However, it is notable that the N10 NAL putative active site is substantially modified from other NAs and has a much wider binding site pocket. The active site residues that are conserved in all other influenza A and B NAs are largely substituted, and its putative active-site loops are displaced from the active site, including the functionally important 150-loop (Fig. 2). Thus, it is not surprising from the sequence and structural data that the N10 NAL exhibits little or no sialidase activity in functional assays, and we suggest that it may have a unique function unrelated to the sialidase activity of other influenza A and B viruses. There is precedent for such altered activity and specificity in influenza C virus, which uses 9-O-acetyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid as a receptor and has 9-O-acetyl esterase activity (26). Although the NAL function is not known, its putative active site contains a large collection of charged and polar residues (Fig. 4), which are potential candidates for either binding or catalysis (27). Alternatively, the bat N10 NAL protein might have a biological function that is completely different from sialic acid receptor cleavage (28). In this regard, it is notable that attempts to propagate bat influenza virus in commonly used influenza virus cell-culture systems have failed (1). Thus, it is possible that NAL receptors on bat tissues differ from other species, such as human, swine, and avian, and a systematic study of receptors on bat cells may be required to understand the biological function of the N10 NAL and identify a suitable cell culture system for the propagation of infectious bat influenza in the laboratory.

Fig. 4.

Putative active or binding site of GU09-164 NAL showing the high number of polar and charged residues and conserved calcium binding site.

The genome sequences of this bat H17N10 virus have revealed that bat influenza viruses have been evolving independently from influenza viruses in other species for an extended period (1). The HA gene has a distinct, but relatively close evolutionary relationship to other influenza HA genes. On average, the GU09-164 H17 has around 50% amino acid sequence identity with group 1 HAs, and 38% identity with group 2 HAs. It was predicted that the H17 might have a similar overall structure to HAs of influenza A viruses, including a generally conserved receptor binding site with the presence of unique amino acids at positions that modulate the galactose-sialic acid linkage specificity. However, the unusual receptor binding site structure and as yet unknown function of N10 NAL now heightens the interest in the structure and function of the H17 HA, as HA and NA normally have opposite functions but act on the same receptor, mediating influenza virus entry and exit during influenza infection and transmission.

In summary, the bat N10 GU09-164 and GU10-060 NA proteins are NA-like in overall 3D structure, but the lack of significant NA activity is highly suggestive of a different function that would give rise to a completely unique mechanism for bat influenza virus entry into cells and subsequent egress to initiate a new infectious cycle in another cell or host. We have focused here on two NAL proteins from influenza viruses that we identified from three bats of 316 tested bats from 21 species at El Jobo, Guatemala (GU09-164 and GU09-153) and Agüero, Guatemala (GU10-060), which are located about 50-km distant from each other (1). With more than 1,200 bat species, which represent about 20% of classified mammal species worldwide, it is likely that additional bat viruses will be discovered increasing the motivation to understand the enigmatic functions of the bat influenza virus surface proteins.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of the N10 NAL Proteins.

The ectodomain (residues 75–442, equivalent to 82–460 in N2 numbering) and ectodomain plus stalk region (30-442, 37-460 in N2 numbering) of N10 NAL proteins from the influenza viruses GU09-164 (GenBank accession no. CY103886) and GU10-060 (GenBank accession no. CY103894) were expressed in a baculovirus system for structural and functional analyses. The cDNAs corresponding to the N10 ectodomain and ectodomain plus stalk region of GU09-164 and GU10-060 NALs were inserted into a baculovirus transfer vector, pFastbacHT-A (Invitrogen) with an N-terminal gp67 signal peptide, a thrombin cleavage site, and a His6-tag (11). The constructed plasmids were used to transform DH10bac competent bacterial cells by site-specific transposition (Tn-7 mediated) to form a recombinant Bacmid with β-galactosidase blue-white receptor selection. The purified recombinant bacmids were used to transfect Sf9 insect cells for overexpression. The N10 NAL proteins were produced by infecting suspension cultures of Hi5 cells with recombinant baculovirus at an multiplicity of infection of 5–10 and incubated at 28 °C shaking at 110 rpm. After 72 h, Hi5 cells were removed by centrifugation and supernatants containing secreted, soluble NAs were concentrated and buffer-exchanged into 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, further purified by metal affinity chromatography using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Qiagen). For crystal structure determination, the N10 NAL ectodomain-only proteins were digested with thrombin to remove the His6-tag. The cleaved N10 NAL ectodomains were purified further by size exclusion chromatography on a Hiload 16/90 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 0.02% NaN3. For solution-based NA activity assays, the uncleaved ectodomain plus stalk region of GU09-164 and GU10-060 NALs with His6-tag attached were concentrated after Ni-NTA purification in 100 mM imidazole-malate pH 6.15, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 0.02% NaN3.

Crystal Structure Determination.

Crystallization experiments were set up using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Diffraction quality crystals (form 1) for GU09-164 NAL ectodomain tetramer were obtained by mixing 0.5 μL protein at 7.9 mg/mL in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 0.02% NaN3 with 0.5 μL of the well solution in 0.2 M Mg nitrate and 14% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 3350 at 22 °C. The GU10-060 NAL ectodomain monomer at 7.2 mg/mL was crystallized in 0.2 M Mg nitrate, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 18% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 4000 at 22 °C. The GU09-164 form 1 crystals were cryoprotected in mother liquor with addition of 25% (vol/vol) glycerol before being flash-cooled at 100 K, and the GU10-060 crystal was flashed-cooled at 100 K without additional cryoprotectant. Diffraction data were collected at beamlines 11–1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource or beamline 23ID-D at the Advanced Photon Source (Table 1). Data for all crystals were integrated and scaled with HKL2000 (29). Data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1.

The GU09-164 and GU10-060 NAL structures were determined by molecular replacement using the program Phaser (30). The GU09-164 NAL structure was first determined using the A/Brevig Mission/1/18 (H1N1) N1 NA structure (PDB ID code 3B7E) (11) as a molecular replacement model. The GU10-060 NAL structure was subsequently determined using the refined GU09-164 NAL structure as an input model. Initial rigid body refinement was performed in REFMAC5 (31), and simulated annealing and restrained refinement (including TLS refinement) were carried out in Phenix (32). Riding hydrogens were added during refinement in Phenix and are included in the final model. Between rounds of refinements, model building was carried out with the program Coot (33). Final statistics for both structures are summarized in Table 1. The quality of the structures was analyzed using the Joint Center for Structural Genomics validation suite (www.jcsg.org). All figures were generated with Bobscript (34), except for Fig. 2 C and D, which were generated with PyMol (www.pymol.org). See Table S2 for data collection and refinement statistics for GU09-164 NAL (crystal form 2).

Neuraminidase Activity Assay with Substrate 4-MU-NANA.

The NA enzymatic activities were measured in 100 mM imidazole-malate pH 6.15, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2 0.02% NaN3 buffer by using fluorescent substrate 4-MU-NANA (35) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 nm and 450 nm, respectively. The reaction was conducted for 60 min at 37 °C in a total volume of 80 μL for N10 proteins with ectodomain plus stalk region that was expressed as a tetramer. The reactions were all performed in triplicate and were stopped by addition of 80 μL of 1 M Na2CO3. To compare activity at different N10 NAL concentration, with a fixed substrate 4-MU-NANA of 0.05 mM, the N10 NAL starting solution at 1.24 mg/mL was serially diluted 1:2 (12 times).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Henry Tien of the Robotics Core at the Joint Center for Structural Genomics for automated crystal screening and Ryan McBride and Corwin Nycholat for assistance in analysis of the NA enzymatic activity of the N10 NAL proteins. X-ray diffraction data sets were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) beamline 11-1 and the Advanced Photon Source beamlines 23ID-D and 22-ID. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant AI058113 (to I.A.W.) and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology. Portions of this research were carried out at the SSRL, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by NIH National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program Grant P41RR001209, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The GM/CA CAT 23-ID-D beamline has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (Y1-CO-1020) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Y1-GM-1104). Supporting institutions for SER-CAT 22-ID may be found at www.ser-cat.org/members.html. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the DOE, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under Contracts DE-AC02-06CH11357 and W-31-109-Eng-38. This is publication 21882 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID codes 4GDI, 4GDJ, and 4GEZ).

See Commentary on page 18635.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1212579109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tong S, et al. A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116200109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Air GM, Laver WG. The neuraminidase of influenza virus. Proteins. 1989;6:341–356. doi: 10.1002/prot.340060402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varghese JN, Laver WG, Colman PM. Structure of the influenza virus glycoprotein antigen neuraminidase at 2.9 Å resolution. Nature. 1983;303:35–40. doi: 10.1038/303035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker AT, Varghese JN, Laver WG, Air GM, Colman PM. Three-dimensional structure of neuraminidase of subtype N9 from an avian influenza virus. Proteins. 1987;2:111–117. doi: 10.1002/prot.340020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell RJ, et al. The structure of H5N1 avian influenza neuraminidase suggests new opportunities for drug design. Nature. 2006;443:45–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu X, Xu X, Wilson IA. Structure determination of the 1918 H1N1 neuraminidase from a crystal with lattice-translocation defects. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;D64:843–850. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908016648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang M, et al. Influenza A virus N5 neuraminidase has an extended 150-cavity. J Virol. 2011;85:8431–8435. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00638-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burmeister WP, Ruigrok RW, Cusack S. The 2.2 A resolution crystal structure of influenza B neuraminidase and its complex with sialic acid. EMBO J. 1992;11:49–56. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colman PM, Varghese JN, Laver WG. Structure of the catalytic and antigenic sites in influenza virus neuraminidase. Nature. 1983;303:41–44. doi: 10.1038/303041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garman E, Laver G. In: Viral Membrane Proteins: Structure, Function, and Drug Design. Fischer W, editor. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2005. pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X, Zhu X, Dwek RA, Stevens J, Wilson IA. Structural characterization of the 1918 influenza virus H1N1 neuraminidase. J Virol. 2008;82:10493–10501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00959-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudrawar S, et al. Novel sialic acid derivatives lock open the 150-loop of an influenza A virus group-1 sialidase. Nat Commun. 2010;1:113. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varghese JN, Colman PM. Three-dimensional structure of the neuraminidase of influenza virus A/Tokyo/3/67 at 2.2 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:473–486. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tulip WR, et al. Refined atomic structures of N9 subtype influenza virus neuraminidase and escape mutants. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:487–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chong AK, Pegg MS, Taylor NR, von Itzstein M. Evidence for a sialosyl cation transition-state complex in the reaction of sialidase from influenza virus. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burmeister WP, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW. Calcium is needed for the thermostability of influenza B virus neuraminidase. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:381–388. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith BJ, et al. Structure of a calcium-deficient form of influenza virus neuraminidase: Implications for substrate binding. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:947–952. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906020063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor NR, von Itzstein M. Molecular modeling studies on ligand binding to sialidase from influenza virus and the mechanism of catalysis. J Med Chem. 1994;37:616–624. doi: 10.1021/jm00031a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janakiraman MN, White CL, Laver WG, Air GM, Luo M. Structure of influenza virus neuraminidase B/Lee/40 complexed with sialic acid and a dehydro analog at 1.8-Å resolution: Implications for the catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8172–8179. doi: 10.1021/bi00193a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong J, Xu W, Zhang J. Structure and functions of influenza virus neuraminidase. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:113–122. doi: 10.2174/092986707779313444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu R, et al. Functional balance of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities accompanies the emergence of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. J Virol. 2012;86:9221–9232. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00697-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor NR, et al. Dihydropyrancarboxamides related to zanamivir: a new series of inhibitors of influenza virus sialidases. 2. Crystallographic and molecular modeling study of complexes of 4-amino-4H-pyran-6-carboxamides and sialidase from influenza virus types A and B. J Med Chem. 1998;41:798–807. doi: 10.1021/jm9703754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenberg EJ, Bidgood A, Cundy KC. Penetration of GS4071, a novel influenza neuraminidase inhibitor, into rat bronchoalveolar lining fluid following oral administration of the prodrug GS4104. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1949–1952. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babu YS, et al. BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): Discovery of a novel, highly potent, orally active, and selective influenza neuraminidase inhibitor through structure-based drug design. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3482–3486. doi: 10.1021/jm0002679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita M, et al. CS-8958, a prodrug of the new neuraminidase inhibitor R-125489, shows long-acting anti-influenza virus activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:186–192. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00333-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers GN, Herrler G, Paulson JC, Klenk HD. Influenza C virus uses 9-O-acetyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid as a high affinity receptor determinant for attachment to cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5947–5951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartlett GJ, Porter CT, Borkakoti N, Thornton JM. Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:105–121. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin YP, et al. Neuraminidase receptor binding variants of human influenza A(H3N2) viruses resulting from substitution of aspartic acid 151 in the catalytic site: A role in virus attachment? J Virol. 2010;84:6769–6781. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00458-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esnouf RM. An extensively modified version of MolScript that includes greatly enhanced coloring capabilities. J Mol Graph Model. 1997;15:132–134, 112–113. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(97)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potier M, Mameli L, Bélisle M, Dallaire L, Melançon SB. Fluorometric assay of neuraminidase with a sodium (4-methylumbelliferyl-alpha-D-N-acetylneuraminate) substrate. Anal Biochem. 1979;94:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.