Abstract

Introduction

Recent years have seen an increasing recognition of the need to improve access and retention in care for people living with HIV/AIDS. This review aims to quantify patients along the continuum of care in sub-Saharan Africa and review possible interventions.

Methods

We defined the different steps making up the care pathway and quantified losses at each step between acquisition of HIV infection and retention in care on antiretroviral therapy (ART). We conducted a systematic review of data from studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and published between 2000 and June 2011 for four of these steps and performed a meta-analysis when indicated; existing data syntheses were used for the remaining two steps.

Results

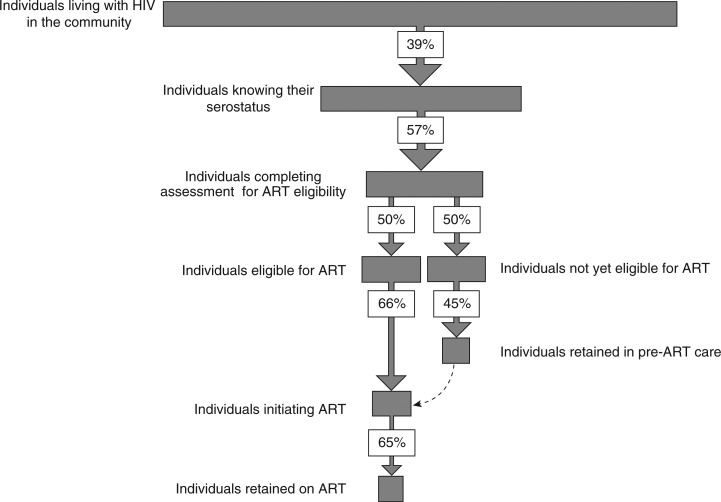

The World Health Organization estimates that only 39% of HIV-positive individuals are aware of their status. Among patients who know their HIV-positive status, just 57% (95% CI, 48 to 66%) completed assessment of ART eligibility. Of eight studies using an ART eligibility threshold of≤200 cells/µL, 41% of patients (95% CI, 27% to 55%) were eligible for treatment, while of six studies using an ART eligibility threshold of≤350 cells/µL, 57% of patients (95% CI, 50 to 63%) were eligible. Of those not yet eligible for ART, the median proportion remaining in pre-ART care was 45%. Of eligible individuals, just 66% (95% CI, 58 to 73%) started ART and the proportion remaining on therapy after three years has previously been estimated as 65%. However, recent studies highlight that this is not a simple linear pathway, as patients cycle in and out of care. Published studies of interventions have mainly focused on reducing losses at HIV testing and during ART care, whereas few have addressed linkage and retention during the pre-ART period.

Conclusions

Losses occur throughout the care pathway, especially prior to ART initiation, and for some patients this is a transient event, as they may re-engage in care at a later time. However, data regarding interventions to address this issue are scarce. Research is urgently needed to identify effective solutions so that a far greater proportion of infected individuals can benefit from long-term ART.

Keywords: HIV, linkage to care, ART, sub-Saharan Africa, retention in care, HIV testing

Introduction

The success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) roll-out in sub-Saharan Africa has been remarkable. Between 2004 and the end of 2011, around 8 million people had initiated ART, leading to dramatic reductions in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality [1–3]. However, due to low HIV test uptake and losses along the pathway between HIV testing and ART treatment [4], only a minority of individuals in need of ART are estimated to ever start treatment [5]. This is further compounded by substantial additional losses that occur during long-term treatment [6,7].

The essential steps in the HIV care pathway for HIV-positive individuals are HIV testing, assessment of eligibility for ART, pre-ART care, initiation of ART and long-term retention on ART. The importance of linkage and engagement in care has received considerable attention in high-income countries [8–10] where successes have resulted in improved health outcomes for the patient [11,12] and reduced costs for the healthcare system [13]. Characterization of losses along the care pathway in high-income countries [13–15] has informed the development of potential interventions [9]. However, the scale of the challenge is so much greater in sub-Saharan Africa where millions of patients are in need of life-long treatment where healthcare systems are less well developed. It is unclear whether interventions developed in high-income countries will be feasible in this resource-constrained setting.

In the majority of sub-Saharan African countries, large scale ART roll-out commenced in 2004 as treatment became affordable and major donor-funding mechanisms were established [16]. The rapid implementation of vertically driven programmes was successful in providing life-saving treatment for large numbers of patients in need. However, this success was achieved with insufficient attention being given to the establishment of the necessary linkages and integration of HIV care within the broader health system. These are essential for the establishment of an effective continuum of care both before and during ART.

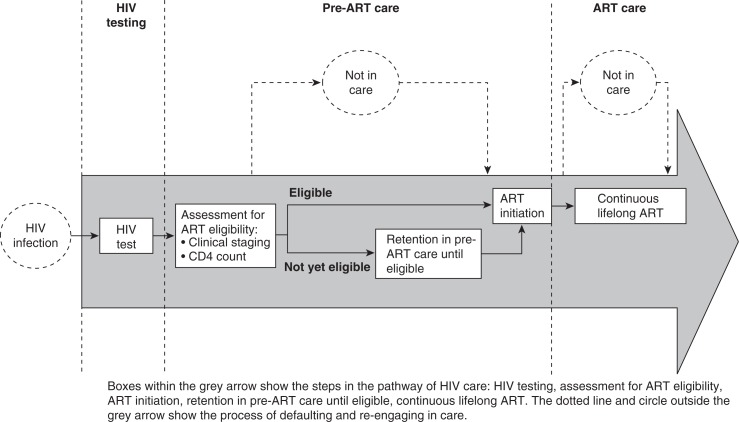

Engagement in HIV care starts when an individual first tests positive for HIV (Figure 1). This should be followed by assessment for ART eligibility, which requires World Health Organization (WHO) clinical staging and/or CD4 count testing. CD4 count testing is a two-stage process, which requires that a patient's blood sample is obtained and sent for processing, followed by the patient returning to receive his or her results (typically 1–2 weeks later). Patients who meet the national criteria for initiation of ART should commence ART without undue delay whereas patients not yet eligible should be retained in pre-ART care and undergo regular CD4 count monitoring until the eligibility threshold is reached. Once patients initiate ART, they should remain on uninterrupted treatment for life. Losses occur at different steps along this pathway, and may be temporary or permanent. The care pathway is not a simple linear process and the dynamic nature of linkage, retention, loss and re-engagement in care, especially in the pre-ART stage, makes this a challenging pathway to assess.

Figure 1.

The care pathway for HIV positive individuals.

To date, the majority of studies from sub-Saharan Africa have focused on treatment adherence and retention of patients who have started ART [6,7,17–20]. However, much more needs to be understood about the earlier components of the care pathway. In addition, most studies have reported on rates and risk factors for loss to care, with little focus on potential interventions. In this article, we review the continuum of HIV care from infection to treatment, quantify losses along the pathway in sub-Saharan Africa, and review interventions to decrease attrition at different points in the pathway.

Methods

Definitions

For the purpose of this review, we have divided the HIV care pathway into (1) HIV testing; (2) pre-ART care comprising assessment of ART eligibility, retention in pre-ART care prior to ART eligibility, initiation of ART; and (3) retention in ART care (Figure 1). Where available, we used synthesized data from published systematic reviews or from WHO reports. Where such data were either unavailable or a more comprehensive review was possible, we conducted systematic literature reviews and data syntheses. Possible interventions and operational solutions aimed to reduce losses at each stage of the pathway are subsequently reviewed and discussed.

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

We sought studies investigating retention in care in the pre-ART period, and linkage to care at three steps: ART eligibility assessment, pre-ART care and ART initiation. Studies were omitted if they were carried out in the private healthcare sector, if they reported unsystematic observations (case reports and case series), or if they were secondary data sources (editorials and viewpoints).

Primary outcomes were the proportion of individuals completing ART assessment, retained in pre-ART care and initiating ART as defined by the authors of the study.

We searched Medline, Embase and Global Health for studies reporting retention between HIV testing and ART using a compound search strategy. Bibliographies of retrieved articles were searched for additional studies. Our search was limited to studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa published between 2000 and June 2011. In addition, we searched for conference abstracts from all conferences of the International AIDS Society (2000–2010), and all Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (2000–2010). No language restriction was applied.

Studies were entered into an electronic database (EndNote X1) to screen potentially eligible studies by title and abstract. Articles were screened by title, then by abstract, independently, and in duplicate (GD, KK). Data was extracted in duplicate (GD, KK) using a standard data extraction form.

Data analysis

We calculated point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the proportion of patients linking to care at various stages of the care pathway. The variance of the raw proportions was stabilized using a Freeman-Tukey type arcsine square-root transformation, and estimates were pooled using a DerSimonian-Laird random effects model. Between study heterogeneity was assessed with the τ2 statistic (on the transformed scale), and subgroup analyses were run to compare studies that used a time cut-off for determining linkage with those that did not. All p values were two-sided, and a p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata (version 11, www.stata.com).

Results

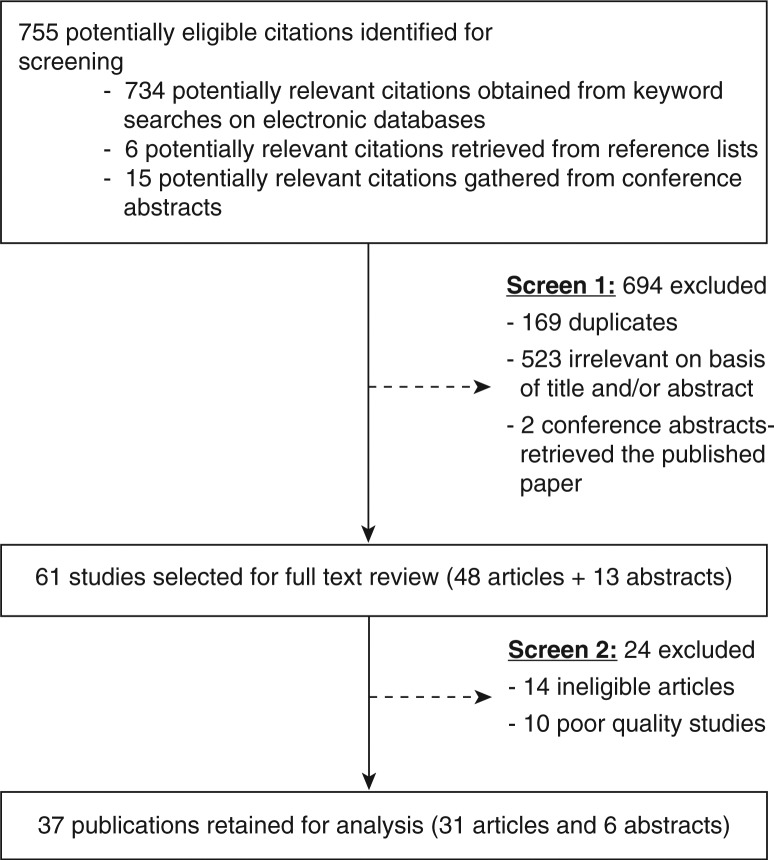

Out of 755 potentially eligible studies, 37 were retained for analysis (Figure 2). Study characteristics are summarized according to the different steps in the pathway (Tables 1–4).

Figure 2.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

Proportion of patients with newly diagnosed HIV infection who complete assessment of eligibility for antiretroviral therapy

| Author | Country | Setting | Year of the study | N | Enrolled into HIV care as a prerequisite of accessing CD4 counts (time cut-off) | Blood sample for CD4 count provided (time cut-off) | Returned for CD4 results (time cut-off) | Enrolled in HIV care (time cut-off) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assefa [21] | Ethiopia | Public sector sites | 2008 | 1314 | 47% (immediately after testing) | |||

| Assefa [21] | Ethiopia | Mobile HIV testing service for high risk individuals | 2008 | 2035 | 26% (two months) | |||

| Mulissa [22] | Ethiopia | Urban, hospital | 2003–08 | 2191 | 70% (no time cut-off, but 49% enrolled the same day) | |||

| Amolloh [23] | Kenya | Asembo, home-based testing service | 2008–09 | 737 | 42% (two to four months) | |||

| Waxman [24] | Kenya | Eldoret, emergency department, hospital | 2006 | 61 | 87% (no time cut-off) | |||

| Gareta [25] | Malawi | Lilongwe, hospital, pregnant women | 2006–08 | 478 | 55% (no time cut-off) | |||

| Tayler Smith [26] | Malawi | Thylo, district hospital, patients with clinical stage I or II | 2008–09 | 1428 | 45% (at least one month follow-up) | |||

| Micek [27] | Mozambique | Urban, HIV testing services | 2004–05 | 7005 | 57% (30 days) | 77% (30 days) | ||

| Braunstein [28] | Rwanda | Kigali, female sex workers | 2007–08 | 141 | 85% (no time cut off) | |||

| April [29] | SA | Cape Town, hospital, primary care clinic | 2006 | 375 | 62% (six months) | |||

| Kranzer [30] | SA | Cape Town, hospital, primary care clinic | 2004–09 | 988 | 63% (six months) | |||

| Larson [31] | SA | Johannesburg, hospital, clinic | 2008–09 | 416 | 85% (12 weeks) | 35% (12 weeks) | ||

| Losina [32] | SA | Durban, semi-private hospital | 2006–07 | 454 | 55% (eight weeks) | 85% (eight weeks) | ||

| Naidoo [33] | SA | Johannesburg, clinic | 225 | 47% (one week) | ||||

| Govindasamy [34] | SA | Cape Town, mobile HIV testing service | 2008–09 | 192 | 73% (no time cut off) | 42% (no time cut off) of those who received their CD4 result | ||

| Bassett [35] | SA | Durban, semi-private hospital | 2006–08 | 1474 | 69% (90 days) | |||

| Ingle [36] | SA | Free State, public sector clinics | 2004–07 | 44844 | 74% (no time cut-off) | |||

| Luseno [37] | SA | Community-based trial | 199 | 46% (no time cut off) | ||||

| Nsigaye [38] | Tanzania | Clinic | 2005–08 | 349 | 68% (no time cut-off) | |||

| Amuron [39] | Uganda | Jinja, clinic | 2004–06 | 2483 | 88% (no time cut-off) | |||

| Wanyenze [40] | Uganda | Kampala, hospital | 2004–05 | 142 | 56% (six months) | |||

| Nakigozi [41] | Uganda | Rakai community cohort study | 1145 | 69% (six months) | ||||

| Wanyenze [42] | Uganda | Kampala, hospital | 2004 | 211 | 48% (three months), 57% (six months) |

Table 4.

Proportions of HIV-positive individuals assessed as eligible for antiretroviral therapy who start treatment

| Author | Country | Setting | Year of the study | N | Linkage to ART care for those eligible (time cut-off) | Median (mean) time to ART initiation | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karcher [17] | Kenya | Nyanza, district hospital | 2004–05 | 159 | 78% (no time cut-off) | 3% died, 13% denied treatment | |

| Tayler-Smith [52] | Kenya | Kibera slum, clinics | 2005–08 | 2471 | 82% (one month) | ||

| Tayler-Smith [26] | Malawi | Thyolo, district hospital, patients with WHO Stage 1/2 and CD4<250 cells/µL | 2008–09 | 681 | 64% (six months) | 33 days (21–44) | |

| Gareta [25] | Malawi | Lilongwe, hospital, pregnant women | 2006–08 | 222 | 69% (four weeks) | ||

| Zachariah [53] | Malawi | Thyolo, district hospital, TB patients | 2003–04 | 742 | 14% (no time cut-off) | ||

| Mcgrath [43] | Malawi | Karonga rural, district hospital | 2005–06 | 659 | 86% (no time cut-off) | 22 days (13–27) | 5% died, 0.5% had moved, 3% alive not taking ART, 5% untraceable |

| Micek [27] | Mozambique | Urban, HIV testing services | 2004–05 | 1506 | 31% (90 days) | 71 days | |

| Kranzer [30] | SA | Cape Town, hospital, primary care clinic | 2004–09 | 219* | 67% (within six months) | ||

| Ingle [36] | SA | Free State, public sector clinics, eligible at first CD4 measurement | 2004–07 | 19089 | 59% (no time cut-off) | 95 days (53–170) | 25% died, 3% in care, 13% not in care |

| Ingle [36] | SA | Free State, public sector clinics, eligible at subsequent CD4 measurement | 2004–07 | 2994 | 58% (no time cut-off) | 13% died, 19% in care, 9% not in care | |

| April [29] | SA | Cape Town, hospital, primary care clinic | 2006 | 72 | 68% (no time cut-off) | ||

| Bassett [54] | SA | Durban, semi-private hospital | 2006 | 501 | 81% (three months) | 6% died, 3% accessed a different service, 0.6% moved away, 0.6% promised to return, 7% were untraceable | |

| Bassett [35] | SA | Durban, semi-private hospital | 2006–08 | 538 | 39% (12 months) | 6.6 months | 17% died |

| Kaplan [55] | SA | Cape Town, primary care clinic, women | 2002–07 | 2131 | 81% (no time cut-off) | 4% died, 7% loss to follow-up | |

| Lawn [56] | SA | Cape Town, primary care clinic | 2002–05 | 1235 | 75% (no time cut-off) | 34 days (28–50) | 5% died, 9% preparing for ART, 11% loss to follow-up |

| Feucht [57] | SA | Pretoria, hospital, children | 2004 | 243 | 40% (no time cut-off) | ||

| Geng [58] | SA | Mbarara, clinic | 2009–10 | 697 | 58% (three months) | ||

| Nunu [47] | Swaziland | Hospital | 2009 | 363 | 58% (on the assigned date) | ||

| Amuron [39] | Uganda | Jinja, clinic | 2004–06 | 2182 | 85% (no time cut-off) | 33 days (15–406) | Survival status was investigated for all losses between testing and treatment (included losses of patients not returning for their CD4 result): 7% died, 8% on ART with a different provider, 6% were alive and not on ART, 4% untraceable |

| Parkes [59] | Uganda | NGOs and governmental health units | 2004–06 | 458 | 61% (three months) |

HIV testing

The proportion of HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa whose infection remains undiagnosed is often derived from population-based surveys in which participants are asked to provide details about previous HIV testing. However, a considerable proportion of those who report a previous negative test may have since seroconverted. Thus, the overall median estimate of 39% of people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa knowing their correct HIV status may be an overestimate [5]. This is suggested by some country-level studies. For example, the Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey linked HIV test results to perceived HIV status [60]. This revealed that among HIV-positive individuals, 56% reported they did not know their status, 28% mistakenly thought they were HIV-negative and only 16% actually knew their HIV-positive status [60]. Similarly, in a peri-urban South African community with high HIV prevalence, the prevalence of previously undiagnosed HIV was 46% despite coverage of HIV testing being high (71%) [61].

Pre-ART care

Assessment of ART eligibility

For individuals who test positive for HIV infection, the next key step in the care pathway is assessment of ART eligibility - a process that might be regarded as indicative of an initial link to care. Of the 22 published studies we identified as eligible for inclusion (Table 1), the majority were conducted in South Africa (n=9). Eleven studies reported the proportions of patients enrolling in care post-diagnosis. Two studies were excluded because they were unrepresentative of the general population accessing clinics and hospitals: one was conducted in a mobile clinic [34] and among female sex workers in Rwanda [28].

The proportion of patients assessed for ART eligibility (reflecting linkage to care) ranged from 42% (95% CI, 39% to 46%) to 70% (95% CI, 68% to 72%), with an overall pooled estimate of 57% (95% CI, 48% to 66%; τ2 0.07). In eight out of the eleven studies, ART eligibility was assessed by CD4 cell count measurement and the proportions of patients in which this was successfully performed ranged from 55% (95% CI, 51% to 60%) to 86% (95% CI, 77% to 94%) with a pooled proportion of 66% (95% CI, 54% to 78%; τ2 0.14). However, only five of these studies reported the number of patients who returned for their test result, with proportions ranging from 30% (95% CI, 26% to 34%) to 88% (95% CI, 87% to 89%) and a pooled estimate of 51% (95% CI, 25% to 78%; τ2 0.40). This pooled estimate is similar to the finding of an earlier systematic review in which a median proportion of 59% completed ART eligibility assessment [4].

Proportion of individuals eligible for ART

We next assessed the proportion of individuals with newly diagnosed HIV infection who were assessed and found to be eligible for ART according to national ART guidelines currently in use at the time of the study. We identified 16 studies eligible for inclusion (Table 2) of which seven were from South Africa. Ten studies reported on the proportions of patients who were eligible for ART based on a CD4 count threshold of ≤200 cells/µL, but two were excluded for reasons of non-generalizability [28,45]. The proportion found to be eligible at this CD4 count threshold ranged from 21% (95% CI, 20% to 22%) to 59% (95% CI, 59% to 60%) with a pooled proportion of 41% (95% CI, 27% to 55%; τ2 0.15). Six studies also reported on the proportions eligible using a CD4 count threshold of ≤350 cells/µL, with proportions ranging from 45% (95% CI, 44% to 47%) to 62% (95% CI, 61% to 63%) and a pooled estimate of 57% (95% CI, 50% to 63; τ2 0.13). Six studies reported on the proportions of patients who were eligible for ART based on clinical criteria (WHO clinical Stage 3 and 4). Proportions ranged from 49% (95% CI, 48% to 51%) to 87% (95% CI, 84% to 89%) with a pooled proportion of 64% (95% CI, 53% to 74%; τ2 0.13).

Table 2.

Proportion of individuals with new HIV diagnoses who are eligible for antiretroviral therapy

| Author | Time | Country | Site | N | CD4<200 | CD4<350 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Eligible | Eligibility criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulissa [22] | 2003–08 | Ethiopia | Clinic | 2191 | 49% | 13.3% | ||||

| Mcgrath [43] | 2005–06 | Malawi | Hospital | 730 | 87% | Stage 3 or 4 | ||||

| Micek [27] | 2004–05 | Mozambique | Clinic | 3046 | 49% | CD4<200 or stage 4, CD4 200 to 350 or stage 3 and pregnant | ||||

| Nakanjako [44] | 2004 | Nigeria | Emergency department | 111 | 49% | 22.0% | ||||

| Braunstein [28] | 2006–07 | Rwanda | FSW | 192 | 11% | 43% | ||||

| Kranzer [30] | 2004–09 | SA | Primary care clinic, hospital | 112 | 34% | 60% | ||||

| van Schaik [45] | 2008–09 | SA | Mobile clinic | 65 | 11% | 25% | ||||

| Basset [35] | 2006–08 | SA | Semi-private hospital | 1012 | 53% | |||||

| Ingle [36] | 2004–07 | SA | Public clinics, hospitals | 33182 | 57% (04)a | |||||

| 54% (05/6) | ||||||||||

| 67% (07) | ||||||||||

| Lessels [46] | 2007 | SA | Clinic | 7655 | 41% | 62% | ||||

| Losina [32] | 2006–07 | SA | Semi-private hospital | 248 | 53% | |||||

| April [29] | 2006 | SA | Primary care clinic, hospital | 375 | 31% | 31% | ||||

| Nunu [47] | 2009 | Swaziland | Hospital | 637 | 57% | Not stated | ||||

| Konde-Lule [48] | Uganda | Public clinics, hospitals | 203 | 36% | 57% | |||||

| Amuron [39] | 2004–06 | Uganda | Clinic | 4321 | 58% | CD4<200 or WHO Stage 4 | ||||

| Carter [49] | 2003–08 | Multisite | ANC, post pregnancy | 6036 | 21% | 45% | 10% | 1% | ||

Proportions were calculated on the basis of calendar years

Pre-ART care prior to ART eligibility

We identified only five studies reporting on retention in care of individuals not yet eligible for ART; four of these were from South Africa (Table 3). The duration of pre-ART care assessed was highly variable between these studies [30,36,46,50]. No study reported the proportion retained in care on becoming eligible for ART. Retention in pre-ART care in South Africa ranged from 41% to 46% [30,36,46,50]. The remaining study from Malawi estimated retention in pre-ART care to be 59% [51]. The median proportion retained in pre-ART care was 45%. As few studies were identified, all with considerable heterogeneity regarding time-cut offs, a pooled estimate was not calculated. Two of the five studies did not specify any time-cut off [30,51], while the other three studies assessed repeat CD4 count measurements or visits — six to twelve months after the initial eligibility assessment [36,46,50].

Table 3.

Retention in care of individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy

| Author | Country | Setting | Year of the study | N | Retention in pre-ART care (time cut off) | Assessment of pre-ART retention | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lessells [46] | SA | Rural Kwazulu Natal, public sector clinics | 2007 | 4223 | 45% (13 months) | repeat CD4 count | |

| Ingle [36] | SA | Free State, public sector clinics | 2004–07 | 11039 | 42% (six months) | Visits | 12% died, 46% loss to follow-up |

| Larson [50] | SA | Johannesburg, hospital, clinic | 2007–08 | 356 | CD4 200 to 350: 6% within four months, 41% within one year CD4 350+: 15% within nine months, 26% within one year | ||

| Kranzer [30] | SA | Cape Town, hospital, primary care clinic | 2004–09 | 419* | 46% (no time cut-off) | Repeat CD4 count | |

| McGuire [51] | Malawi | Rural Malawi, district hospital, clinics | 2004–07 | 5685 | 59% (no time cut-off) | 3% known dead, 6% transferred out, 31% loss to follow-up (a sample of the patients lost to follow-up were traced: 26% were alive, 35% were dead, 10% moved, 29% were not found) |

Initiation of ART

We identified 19 studies that reported the proportions of ART-eligible individuals who started ART (“linkage to ART”) (Table 4). Ten studies in seven sites were conducted in South Africa with the remainder conducted in Kenya (n=1), Malawi (n=4), Mozambique (n=1), Swaziland (n=1) and Uganda (n=2). A study reporting linkage amongst TB, co-infected patients was excluded from the meta-analysis as these patients have an unrepresentative high mortality risk [53]. In the remaining 18 studies, the proportion linking to ART ranged from 31% (95% CI, 29% to 33%) to 86% (95% CI, 83% to 89%), with an overall pooled proportion of 66% (95% CI, 58% to 73%; τ2 0.12). An earlier review of 14 studies found the median proportion of individuals initiating ART was 68% [4]. Eight of the studies included in our meta-analysis did not specify the time period within which patients could link to ART care. However, in a subgroup analysis there was no difference in the proportion linking to ART care comparing studies that used a time cut-off for determining a link with those that did not (p=0.24). Studies which reported on time between HIV testing or staging and initiation of ART showed that the majority of patients started treatment within one month; however, two studies reported median delays of between 2.4 and 6.6 months [27,35].

Eight studies assessed the contribution of mortality as a potential cause for not starting ART and reported a median mortality of 5.5% (interquartile range=4.5% to 12%) among eligible patients waiting to start treatment [17,35,36,39,43,54,56]. In these studies, it is difficult to ascertain whether death is the cause or the result of not starting ART. Some studies traced individuals who were thought to have not started ART [39,54]; between 3% and 19% of such patients were either retained in care in the same clinical service or had accessed treatment elsewhere.

ART care

Patients receiving ART may leave clinical care for three reasons: death, transfer of care to another service (transfer-out) and loss to follow-up. Losses during ART are much better documented than those occurring earlier in the care pathway. Early mortality is typically high in programmes in sub-Saharan Africa [62]. Systematic reviews have estimated that death accounted for around 40% of patient attrition during the first two to three years of treatment [6,7]. Key risk factors for this include a low baseline CD4 count and advanced WHO stage of disease [63]. Thus, interventions upstream in the care pathway are needed to prevent late presentation. Long-term mortality risk decreases substantially [63–66], especially once a CD4 cell count threshold of 200 cells/µL has been exceeded [67].

Early in the scale-up of ART in sub-Saharan Africa, treatment sites were few; patients were typically severely immunocompromised at the time of ART initiation; and prognosis was uncertain. Thus, transfer of patient care between ART clinics was relatively uncommon. However, over time the number of decentralized treatment sites has expanded; patients are generally less immunocompromised when commencing ART; and patient confidence in ART has grown [65]. These factors may explain why in some settings, rates of transfer between services have risen steeply [64,68]. Data on true outcomes of patients transferred from one program to another are scarce [69,70], but if transfer of care is successful, then the patient is effectively retained in care.

A challenge to rapidly expanding ART programmes in sub-Saharan Africa is the issue of preventing “losses to follow-up.” Patients are usually classified as “lost to follow-up” if they fail to attend follow-up appointments over a specified duration without having been actively transferred to another ART clinic, and if they are not known to have died. A systematic review of 39 ART cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa reported an average retention of 65% at three years [6]. In recent years, many ART cohorts have rapidly increased in size with disproportionate increases in the number of patients compared to the number of healthcare workers. Losses to follow-up have reportedly grown over successive calendar periods, indicating a growing problem with long-term retention in care [64,65,71].

Defining a patient as “lost to follow-up” is often based on exclusion of other known reasons for failure of the patient to attend. However, this may conceal considerable unascertained mortality. A systematic review summarizing studies that traced individuals lost to follow-up showed that on average 40% of such individuals had actually died [72]. A study from South Africa reported that 78% of such deaths occurred within the first three months after their last clinic visit [71], suggesting these deaths were the reason and not the result of being lost to follow-up.

Another complexity in reporting rates of loss to follow-up is that patients may cycle in and out of care. Thus, patients who fulfil the widely used definition of loss to follow-up at one time point might re-engage with care at a later stage and thus cease to be lost to follow-up. A systematic review of this issue conducted in 2011 identified nine studies from sub-Saharan Africa and found that an average of 12% of individuals on ART had previously interrupted but subsequently restarted treatment [73].

Cumulative losses along the pathway

No study has yet measured the cumulative losses occurring along the entire care pathway. This would require long-term prospective demographic surveillance, although such a process in itself would likely alter the outcomes of interest. An alternative approach is to combine pooled estimates of losses from each of the steps in the care pathway that we have described. However, using data in this way from cross-sectional studies with typically short duration of follow-up is methodologically flawed [4]. A critical issue is that the care pathway is not a simple linear process and patients clearly cycle in and out of care; a patient who fails to complete one step in the pathway may re-engage with the treatment pathway at a later time-point and ultimately receive successful long-term ART. Thus, use of the individual estimates of the losses described thus far and summarized in Figure 3 might erroneously lead to the conclusion that of all HIV-positive individuals in the community, only 7% (0.39×0.57×0.50×0.66) would start ART and 5% (0.039×0.57×0.50×0.45) would be retained in pre-ART care for some duration.

Figure 3.

Cumulative losses along the HIV care pathway as reported by cross-sectional studies addressing each step in the pathway. The proportions (%) shown indicate the proportions of individuals who successfully complete each step in the pathway.

The assertion that these are likely to be underestimates of the true proportions receiving care is supported by detailed data from a high HIV prevalence community in South Africa. In a population-based sero-prevalence survey, 54% of all HIV-positive individuals knew their positive HIV sero-status [61]. A study of this community from the same period showed that 63% of HIV-positive individuals were assessed for ART eligibility within six months of diagnosis, 26% were eligible for ART and 66% started ART within six months of diagnosis [30]. Combining these estimates of losses along the HIV care pathway in this community would lead to an estimated ART coverage in the community of 6% (0.54×0.63×0.26×0.66), whereas in reality a population-based survey reported a coverage of 33.5%, which is more than five-fold higher [61]. This illustrates the complexities involved in studying the HIV care pathway and the need for better means of assessment.

Interventions

Multiple interventions are needed to address high rates of patient attrition at every stage of the HIV care pathway. Strategies to reduce deaths among patients who have started ART have been described elsewhere [74], so instead, we should focus on strategies to increase HIV diagnosis and engagement of patients in pre-ART care and aim to reduce losses to follow-up throughout the pathway.

Interventions either aim to increase the efficiency and capacity of services, or accessibility and acceptability of these services (Table 5). Interventions to increase HIV testing include task-shifting (testing through lay healthcare workers) [77–79] and provider-initiated testing [89–91] as well as mobile, community, home-based and workplace services 83–87,92] which bring the service nearer to the patient and thus increase accessibility, which might in turn increase acceptability. Other interventions aimed to increase acceptability of testing are self-testing [80] and incentivized testing [93,94]. More recently, community-based strategies for HIV testing and ART delivery have been developed [84,88,99] as a way to further expand access to care. By virtue of being placed in the community, these strategies are decentralized and use task-shifting to engage lesser trained health staff, and thus might be more cost-effective [125].

Table 5.

Interventions to increase HIV diagnosis and engagement of patients in pre-ART HIV care and to reduce losses to follow-up throughout the care pathway

| Step | Targeting | Intervention/operational solution | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV testing capacity |

|

||

| HIV testing | Demand for HIV testing |

|

|

| Completion of staging and linkage to pre-ART and ART care |

|

||

|

| |||

| Pre-ART care | Retention in pre-ART care prior to ART eligibility |

|

|

|

|||

| ART care | Increase retention |

|

|

| Increase re-initiation for treatment interrupters |

|

||

Only four studies have assessed interventions aimed at reducing losses in the pre-ART period. These have examined point-of-care CD4 count testing [95,96], more efficient referral systems [38], transport vouchers [38] and regular visits to refill trimethoprim-sulphmethoxazole prophylaxis [97]. In contrast, many studies have reported on interventions to reduce loss to follow-up of patients on ART [126]. Some of these interventions are structural such as task-shifting [104–108], decentralization [77,106,108–111], integration [114,115] and continuous drug supply [118,119], whereas others are aimed at the individual such as adherence counselling [101,102] and transport reimbursement [118,120,121].

Few interventions have been assessed for their efficacy and cost-effectiveness in randomized controlled trials [83,92,94,104,116], and most observational studies have assessed feasibility rather than effectiveness [80,114,123]. Evidence for a positive effect of, for example, transport vouchers and secured drug supplies comes mainly from risk factor analysis and semi-qualitative studies [118–121]. Some interventions have only been assessed for one specific step in the pathway, but not for others. An example is adherence counselling, which has been shown to have some effect on retention in ART care [101,102], but the effect of counselling on retention in pre-ART care or on linkage to ART care has not yet been formally assessed.

Integration of care has mainly concentrated on tuberculosis and PMTCT programs [115,127] or the beneficial effects derived by other health services through the integration of HIV care [128]. The lack of a common conceptual framework on what integration means has impeded more rigorous evaluation of the impact of integration on retention and testing [129]. One study conducted in nine countries in sub-Saharan Africa, found that providing ART in an integrated approach resulted in substantially less defaulting from care compared to vertical ART delivery [130]. As HIV is a chronic disease, integration is important not only to improve retention, but also to provide comprehensive care (Table 6). This has been conceptualized in the WHO's Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness programme [131].

Table 6.

Comprehensive HIV care

| Prevention |

| Trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole prophylaxis |

| Isoniazid preventive therapy |

| Intensified tuberculosis case finding |

| Cryptococcal antigen screening |

| Cervical cancer screening |

| Prevention of mother to child transmission |

| Prevention of transmission to sexual partners |

| Acute services |

| Tuberculosis |

| Mental health |

| Sexual transmitted diseases |

| Antenatal care |

| Family planning |

| Chronic services |

| Mental health |

| Chronic disease (e.g. diabetes, ophthalmological services, etc.) |

| Care of the elderly services |

| Social support |

Conclusions

Substantial losses occur at every stage of the HIV care pathway for HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa. Assessment of these losses is complex as is engagement in care; loss to care and return to care is a dynamic, non-linear and time-dependent process. To date, no study has yet defined the cumulative losses throughout the pathway. Data regarding interventions to address these losses are scarce, especially with regards to the care pathway prior to ART initiation. Research is urgently needed to identify effective solutions so that a far greater proportion of HIV-positive individuals can reap the benefits of ART. Such research should take into account the important gender differences that are becoming increasingly apparent with respect to accessing testing [132] and treatment and care [133].

The “test and treat” approach to reducing HIV transmission proposes that very high coverage of HIV testing and immediate initiation of ART regardless of the stage of HIV progression would substantially reduce HIV transmission [134], and has been met with considerable enthusiasm. The data in this review serve as a reminder of the huge operational challenges that will be faced in implementing such a strategy. Considerable investment and energy must be devoted to identifying effective interventions to strengthen the care pathway, thereby permitting more effective implementation of current policy. As the care pathway is strengthened, “test and treat” will become a more viable strategy.

Acknowledgements

KK, VJ, SDL are funded by the Wellcome Trust, London, UK. The funding sources played no role in the decision to publish these data.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' contributions

KK and SDL were responsible for the outline of the paper. KK and DG conducted the literature searches and data extraction. The meta-analysis was performed by NF and KK. KK and SDL wrote the paper with input from DG, NF, VJ. All authors contributed to, read and approved the final paper.

References

- 1.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egger M, May M, Chene G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahn A, Floyd S, Crampin AC, Mwaungulu F, Mvula H, Munthali F, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Lancet. 2008;371:1603–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. accessed 2011 May 31. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2010progressreport/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-infected patients in care: their lives depend on it. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1500–2. doi: 10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mugavero MJ, Norton WE, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S238–46. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, Routman JS, Abroms S, Allison J, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:41–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Ulett KB, Routman JS, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:248–56. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–9. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horstmann E, Brown J, Islam F, Buck J, Agins BD. Retaining HIV-infected patients in care: where are we? Where do we go from here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:752–61. doi: 10.1086/649933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24:2665–78. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Stein MD, Lewis R, Savetsky J, Sullivan L, et al. Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:734–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartlander B, Grubb I, Perriens J. The 10-year struggle to provide antiretroviral treatment to people with HIV in the developing world. Lancet. 2006;368:541–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karcher H, Omondi A, Odera J, Kunz A, Harms G. Risk factors for treatment denial and loss to follow-up in an antiretroviral treatment cohort in Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:687–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Myer L, Bangsberg DR, Boulle A, Nash D, et al. Early loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programmes in lower-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:559–67. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawn SD, Myer L, Orrell C, Bekker LG, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing a community-based antiretroviral service in South Africa: implications for programme design. AIDS. 2005;19(18):2141–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194802.89540.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairall LR, Bachmann MO, Louwagie GM, van Vuuren C, Chikobvu P, Stevan D, et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program: a cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:86–93. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assefa Y, Van Damme W, Mariam DH, Kloos H. Toward universal access to HIV counseling and testing and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: looking beyond HIV testing and ART initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:521–5. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulissa Z, Jerene D, Lindtjorn B. Patients present earlier and survival has improved, but pre-ART attrition is high in a six-year HIV cohort data from Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amolloh M, Medley A, Owuor P, Audi B, Sewe M. Factors associated with early uptake of HIV care and treatment services after testing HIV-positive during home based testing and counseling (HBCT) in rural Western Kenya. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 28 February–3 March 2011; Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America. Abstract 1077. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waxman MJ, Kimaiyo S, Ongaro N, Wools-Kaloustian KK, Flanigan TP, Carter EJ. Initial outcomes of an emergency department rapid HIV testing program in western Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:981–6. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gareta D, Tweya H, Weigel R, Phiri S, Chiwoko J, et al. Linking HIV-infected pregnant women to antiretroviral therapy: experience from Lilongwe, Malaw. XVIII International AIDS Conference 2010; Vienna, Austria. Abstract MOPE0277. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Massaquoi M, Manzi M, Pasulani O, Bemelmans M, et al. Unacceptable attrition among WHO stages 1 and 2 patients in a hospital-based setting in rural Malawi: can we retain such patients within the general health system? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Micek MA, Gimbel-Sherr K, Baptista AJ, Matediana E, Montoya P, Pfeiffer J, et al. Loss to follow-up of adults in public HIV care systems in central Mozambique: identifying obstacles to treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:397–405. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab73e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braunstein SL, Umulisa MM, Veldhuijzen NJ, Kestelyn E, Ingabire CM, Nyinawabega J, et al. HIV diagnosis, linkage to HIV care, and HIV risk behaviors among newly diagnosed HIV positive female sex workers in Kigali, Rwanda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:e70–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182170fd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.April MD, Walensky RP, Chang Y, Pitt J, Freedberg KA, Losina E, et al. HIV testing rates and outcomes in a South African community, 2001–2006: implications for expanded screening policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:310–6. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a248e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P, Orrell C, Kalaw NN, Lawn SD, et al. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, Lawrence L, Rosen S, Sanne I, et al. Lost opportunities to complete CD4+ lymphocyte testing among patients who tested positive for HIV in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:675–80. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Losina E, Bassett IV, Giddy J, Chetty S, Regan S, Walensky RP, et al. The “ART” of linkage: pre-treatment loss to care after HIV diagnosis at two PEPFAR sites in Durban, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naidoo N, Faal M, Venter F, Osih R. Patient retention - reasons why patients do or do not come back to care after HIV testing. XVIII International AIDS Conference 2010; Vienna, Austria. Abstract THPE0798. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Govindasamy D, van Schaik N, Kranzer K, Wood R, Mathews C, Bekker LG. Linkage to HIV care from a mobile testing unit in South Africa by different CD4 count strata. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:344–52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822e0c4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassett IV, Regan S, Chetty S, Giddy J, Uhler LM, Holst H, et al. Who starts antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa? … not everyone who should. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 1):S37–44. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000366081.91192.1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingle SM, May M, Uebel K, Timmerman V, Kotze E, Bachmann M, et al. Outcomes in patients waiting for antiretroviral treatment in the Free State Province, South Africa: prospective linkage study. AIDS. 2010;24:2717–25. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833fb71f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luseno W, Wechsberg W, Middlesteadt-Ellerson R, Gumula W. Linkages and barriers to care for high-risk South African women testing positive for HIV. XVII International AIDS Conference 2008; Mexico City, Mexico. Abstract TUPE0209. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nsigaye R, Wringe A, Roura M, Kalluvya S, Urassa M, Busza M, et al. From HIV diagnosis to treatment: evaluation of a referral system to promote and monitor access to antiretroviral therapy in rural Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:31. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amuron B, Namara G, Birungi J, Nabiryo C, Levin J, Grosskurth H, et al. Mortality and loss-to-follow-up during the pre-treatment period in an antiretroviral therapy programme under normal health service conditions in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:290. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wanyenze RK, Hahn JA, Liechty CA, Ragland K, Ronald A, Mayanja-Kizza H, et al. Linkage to HIV care and survival following inpatient HIV counseling and testing. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:751–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9704-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakigozi G, Makumbi F, Reynolds S, Galiwango R, Kagaayi J, Nalugoda F, et al. Non-enrollment for free community HIV care: findings from a population-based study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2011;23:764–70. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wanyenze R, Bangasberg D, Liechty C, Nansubuga J, Kasakye H, et al. Linkage to care and mortality at 18 month follow-up in a cohort of newly diagnosed HIV-positive inpatients in Mulago Hospital, Uganda. XVI International AIDS Conference 2006; Toronto, Canada. Abstract THPE0207. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGrath N, Glynn JR, Saul J, Kranzer K, Jahn A, Mwaungulu F, et al. What happens to ART-eligible patients who do not start ART? Dropout between screening and ART initiation: a cohort study in Karonga, Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakanjako D, Kyabayinze DJ, Mayanja-Kizza H, Katabira E, Kamya MR. Eligibility for HIV/AIDS treatment among adults in a medical emergency setting at an urban hospital in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2007;7:124–8. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2007.7.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Schaik N, Kranzer K, Wood R, Bekker LG. Earlier HIV diagnosis - are mobile services the answer? S Afr Med J. 2010;100:671–4. doi: 10.7196/samj.4162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Cooke GS, Newell ML. Retention in HIV care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e79–86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182075ae2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nunu RP, Nkambule L, Kamiru H, Vandelanotte J, Preko P, et al. Using phone follow-up system to understand barriers to ART initiation at Good Shepherd hospital in Swaziland. XVIII International AIDS Conference 2010; Vienna, Austria. Abstract MOPE0922. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konde-Lule J, Makumbi F, Pakker N, Muyinda A, Mubiru M, Cobelens FG. Effect of changing antiretroviral treatment eligibility criteria on patient load in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2011;23:35–41. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter RJ, Dugan K, El-Sadr WM, Myer L, Otieno J, Pungpapong N, et al. CD4+ cell count testing more effective than HIV disease clinical staging in identifying pregnant and postpartum women eligible for antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:404–10. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e73f4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, Long L, Rosen S, Sanne I, et al. Early loss to follow up after enrolment in pre-ART care at a large public clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):43–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGuire M, Munyenyembe T, Szumilin E, Heinzelmann A, Le Paih M, Bouithy N, et al. Vital status of pre-ART and ART patients defaulting from care in rural Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, Kizito W, Vandenbulcke A, Dunkley S, et al. Demographic characteristics and opportunistic diseases associated with attrition during preparation for antiretroviral therapy in primary health centres in Kibera, Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:579–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zachariah R, Harries AD, Manzi M, Gomani P, Teck R, Phillips M, et al. Acceptance of anti-retroviral therapy among patients infected with HIV and tuberculosis in rural Malawi is low and associated with cost of transport. PLoS One. 2006;1:e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bassett IV, Wang B, Chetty S, Mazibuko M, Bearnot B, Giddy J, et al. Loss to care and death before antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:135–9. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a44ef2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan R, Orrell C, Zwane E, Bekker LG, Wood R. Loss to follow-up and mortality among pregnant women referred to a community clinic for antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2008;22:1679–81. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830ebcee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lawn SD, Myer L, Harling G, Orrell C, Bekker LG, Wood R. Determinants of mortality and nondeath losses from an antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa: implications for program evaluation. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:770–6. doi: 10.1086/507095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feucht UD, Kinzer M, Kruger M. Reasons for delay in initiation of antiretroviral therapy in a population of HIV-infected South African children. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:398–402. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geng EH, Bwana MB, Kabakyenga J, Muyindike W, Emenyonu NI, Musinguzi N, et al. Diminishing availability of publicly funded slots for antiretroviral initiation among HIV-infected ART-eligible patients in Uganda. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parkes R, Namakoola I, Todd J, Kalanzi I, Hiarlaithe M, et al. Barriers to rapid initiation of ART in a cohort of HIV positive Ugandan adults with CD4 counts less than 200. XVI International AIDS Conference; Toronto, Canada. Abstract WEPE0079. [Google Scholar]

- 60.NACC. Kenya AIDS indicator survey 2007 final report; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kranzer K, van Schaik N, Karmue U, Middelkoop K, Sebastian E, Lawn SD, et al. High prevalence of self-reported undiagnosed HIV despite high coverage of HIV testing: a cross-sectional population based sero-survey in South Africa. PLos One. 2011;6:e25244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nglazi MD, Lawn SD, Kaplan R, Kranzer K, Orrell C, Wood R, et al. Changes in programmatic outcomes during 7 years of scale-up at a community-based antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e1–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ff0bdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boulle A, Van Cutsem G, Hilderbrand K, Cragg C, Abrahams M, Mathee S, et al. Seven-year experience of a primary care antiretroviral treatment programme in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 2010;24:563–72. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333bfb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boulle A, Bock P, Osler M, Cohen K, Channing L, Hilderbrand K, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and early mortality in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:678–87. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lawn SD, Little F, Bekker LG, Kaplan R, Campbel E, Orrell C, et al. Changing mortality risk associated with CD4 cell response to antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:335–42. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321823f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Geng EH, Glidden DV, Bwana MB, Musinguzi N, Emenyonu N, Muyindike W, et al. Retention in care and connection to care among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Africa: estimation via a sampling-based approach. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu JK, Tok TS, Tsai JJ, Chang WS, Dzimadzi RK, Yen PH, et al. What happens to patients on antiretroviral therapy who transfer out to another facility? PLoS One. 2008;3:e2065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Connor C, Osih R, Jaffer A. Loss to follow-up of stable antiretroviral therapy patients in a decentralized down referral model of care in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:429–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230d507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Cutsem G, Ford N, Hildebrand K, Goemaere E, Mathee S, Abrahams M, et al. Correcting for mortality among patients lost to follow up on antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a cohort analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kranzer K, Ford N. Unstructured treatment interruption of antiretroviral therapy in clinical practice: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1297–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Wood R. Strategies to reduce early morbidity and mortality in adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:18–26. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328333850f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huerga H, Spillane H, Guerrero W, Odongo A, Varaine F. Impact of introducing human immunodeficiency virus testing, treatment and care in a tuberculosis clinic in rural Kenya. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:611–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harris JB, Hatwiinda SM, Randels KM, Chi BH, Kancheya NG, Jham MA, et al. Early lessons from the integration of tuberculosis and HIV services in primary care centers in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:773–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bemelmans M, van den Akker T, Ford N, Philips M, Zachariah R, Harries A, et al. Providing universal access to antiretroviral therapy in Thyolo, Malawi through task shifting and decentralization of HIV/AIDS care. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:1413–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McCollum ED, Preidis GA, Kabue MM, Singogo EB, Mwansambo C, Kazembe PN, et al. Task shifting routine inpatient pediatric HIV testing improves program outcomes in urban Malawi: a retrospective observational study. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bradley H, Bedada A, Tsui A, Brahmbhatt H, Gillespie D, Kidanu A. HIV and family planning service integration and voluntary HIV counselling and testing client composition in Ethiopia. AIDS Care. 2008;20:61–71. doi: 10.1080/09540120701449112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choko A, Desmond N, Webb E, Chavula K, Mavedzenge S, et al. Feasibility, accuracy, and acceptability of using oral HIV test kits for supervised community-level self-testing in a resource-poor high-HIV prevalence setting: Blantyre, Malawi. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, USA. Abstract 42. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lafort Y, Geelhoed D, Cumba L, Lazaro CD, Delva W, Luchters S, et al. Reproductive health services for populations at high risk of HIV: performance of a night clinic in Tete province, Mozambique. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:144. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375:1014–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sweat M, Morin S, Celentano D, Mulawa M, Singh B, Mbwambo J, et al. Community-based intervention to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16–32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043): a randomised study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:525–32. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mutale W, Michelo C, Jurgensen M, Fylkesnes K. Home-based voluntary HIV counselling and testing found highly acceptable and to reduce inequalities. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:347. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grabbe KL, Menzies N, Taegtmeyer M, Emukule G, Angala P, Mwega I, et al. Increasing access to HIV counseling and testing through mobile services in Kenya: strategies, utilization, and cost-effectiveness. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:317–23. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ced126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wringe A, Isingo R, Urassa M, Maiseli G, Manyalla R, Changalucha J, et al. Uptake of HIV voluntary counselling and testing services in rural Tanzania: implications for effective HIV prevention and equitable access to treatment. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:319–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ostermann J, Reddy EA, Shorter MM, Muiruri C, Mtalo A, Itemba DK, et al. Who tests, who doesn't, and why? Uptake of mobile HIV counseling and testing in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lugada E, Levin J, Abang B, Mermin J, Mugalanzi E, Namara G, et al. Comparison of home and clinic-based HIV testing among household members of persons taking antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: results from a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:245–52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9e069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Silvestri DM, Modjarrad K, Blevins ML, Halale E, Vermund SH, McKinzie JP, et al. A comparison of HIV detection rates using routine opt-out provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling versus a standard of care approach in a rural African setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e9–32. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181fdb629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bassett IV, Giddy J, Nkera J, Wang B, Losina E, Lu Z, et al. Routine voluntary HIV testing in Durban, South Africa: the experience from an outpatient department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:181–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814277c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kharsany AB, Karim QA, Karim SS. Uptake of provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling among women attending an urban sexually transmitted disease clinic in South Africa - missed opportunities for early diagnosis of HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2010;22:533–7. doi: 10.1080/09540120903254005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Corbett EL, Dauya E, Matambo R, Cheung YB, Makamure B, Bassett MT, et al. Uptake of workplace HIV counselling and testing: a cluster-randomised trial in Zimbabwe. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thornton R. Cambridge: Havard University; 2005. The impact of incentives on learning HIV status: evidence from a field experiment. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thornton R. The demand for and impact of learning HIV Status: evidence from a field experiment. Cambridge: Havard University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Faal M, Naidoo N, Glencross DK, Venter WD, Osih R. Providing immediate CD4 count results at HIV testing improves ART initiation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:e54–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182303921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jani I, Sitoe N, Alfai E, Chongo P, Lehe J. Point-of-care CD4 improves patient rentention and time-to-initiation of ART in Mozambique. XVIII International AIDS Conference 2010; Vienna, Austria. Abstract FRLBE101. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kohler P, Chung M, Benki-Nugent S, McGrath C, Attwa M, et al. Free CTX Substantially Improves Retention among ART-ineligible Clients in a Kenyan HIV Treatment Program. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2011; Boston, USA. Abstract 1018. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, Birungi J, Levin J, Namara G, et al. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2009;374:2080–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Decroo T, Telfer B, Biot M, Maikere J, Dezembro S, Cumba LI, et al. Distribution of antiretroviral treatment through self-forming groups of patients in Tete province, Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;56(2):e39–44. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182055138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zachariah R, Teck R, Buhendwa L, Fitzerland M, Labana S, Chinji C, et al. Community support is associated with better antiretroviral treatment outcomes in a resource-limited rural district in Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Etienne M, Burrows L, Osotimehin B, Macharia T, Hossain B, Redfield RR, et al. Situational analysis of varying models of adherence support and loss to follow up rates; findings from 27 treatment facilities in eight resource limited countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Torpey KE, Kabaso ME, Mutale LN, Kamanga MK, Mwango AJ, Simpungwe J, et al. Adherence support workers: a way to address human resource constraints in antiretroviral treatment programs in the public health setting in Zambia. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boyd MA. Improvements in antiretroviral therapy outcomes over calendar time. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4:194–9. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328329fc8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sanne I, Orrell C, Fox MP, Conradie F, Ive P, Zeinecker J, et al. Nurse versus doctor management of HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy (CIPRA-SA): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;376:33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60894-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Selke HM, Kimaiyo S, Sidle JE, Vedanthan R, Tierney WM, Shen C, et al. Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:483–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181eb5edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Long L, Brennan A, Fox MP, Ndibongo B, Jaffray I, Sanne I, et al. Treatment outcomes and cost-effectiveness of shifting management of stable ART patients to nurses in South Africa: an observational cohort. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bolton-Moore C, Mubiana-Mbewe M, Cantrell RA, Chintu N, Stringer EM, Chi BH, et al. Clinical outcomes and CD4 cell response in children receiving antiretroviral therapy at primary health care facilities in Zambia. JAMA. 2007;298:1888–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cohen R, Lynch S, Bygrave H, Eggers E, Vlahakis N, Hilderbrand K, et al. Antiretroviral treatment outcomes from a nurse-driven, community-supported HIV/AIDS treatment programme in rural Lesotho: observational cohort assessment at two years. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brennan A, Long L, Maskew M, Sanne I, Jaffray I, Macphail P, et al. Outcomes of stable HIV-positive patients down-referred from doctor-managed ART clinics to nurse-managed primary health clinics for monitoring and treatment. AIDS. 2011;25(16):2027–36. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fatti G, Grimwood A, Bock P. Better antiretroviral therapy outcomes at primary healthcare facilities: an evaluation of three tiers of ART services in four South African provinces. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bedelu M, Ford N, Hilderbrand K, Reuter H. Implementing antiretroviral therapy in rural communities: the Lusikisiki model of decentralized HIV/AIDS care. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S464–8. doi: 10.1086/521114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chan AK, Mateyu G, Jahn A, Schouten E, Arora P, Mlotha W, et al. Outcome assessment of decentralization of antiretroviral therapy provision in a rural district of Malawi using an integrated primary care model. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):90–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Massaquoi M, Zachariah R, Manzi M, Pasulani O, Misindi D, Mwagomba B, et al. Patient retention and attrition on antiretroviral treatment at district level in rural Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Topp SM, Chipukuma JM, Giganti M, Mwango LK, Chiko LM, Tambatamba-Chapula B, et al. Strengthening health systems at facility-level: feasibility of integrating antiretroviral therapy into primary health care services in Lusaka, Zambia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tudor Car L, van-Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, Elmoniry H, Car J, Majeed A, et al. Integrating prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) programmes with other health services for preventing HIV infection and improving HIV outcomes in developing countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6:CD008741. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008741.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, Zivin JG, Goldstein MP, de Walque D, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS. 2011;25:825–34. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834380c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kunutsor S, Walley J, Katabira E, Muchuro S, Balidawa H, Namagala E, et al. Using mobile phones to improve clinic attendance amongst an antiretroviral treatment cohort in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional and prospective study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1347–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9780-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wenkel J, van den Boogard W, O'Brian D, Botha Standaert E, Braker K, et al. Adverse consequences of user fees for patients started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the governmental HIV-programs in Nigeria. XVI International AIDS conference; Toronto, Canada. Abstract THPDD05. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pasquet A, Messou E, Gabillard D, Minga A, Depoulosky A, Deuffic-Burban S, et al. Impact of drug stock-outs on death and retention to care among HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dahab M, Kielmann K, Charalambous S, Karstaedt AS, Hamilton R, La Grange L, et al. Contrasting reasons for discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy in workplace and public-sector HIV programs in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:53–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:405–11. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ford N, Kranzer K, Hilderbrand K, Jouquet G, Goemaere E, Vlahakis N, et al. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy and associated reduction in mortality, morbidity and defaulting in a nurse-managed, community cohort in Lesotho. Aids. 2010;24:2645–50. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ec5b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rosen S, Ketlhapile M. Cost of using a patient tracer to reduce loss to follow-up and ascertain patient status in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Krebs DW, Chi BH, Mulenga Y, Morris M, Cantrell RA, Levy J, et al. Community-based follow-up for late patients enrolled in a district-wide programme for antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Care. 2008;20:311–7. doi: 10.1080/09540120701594776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Babigumira JB, Castelnuovo B, Stergachis A, Kiragga A, Shaefer P, Lamorde M, et al. Cost effectiveness of a pharmacy-only refill program in a large urban HIV/AIDS clinic in Uganda. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Harries AD, Zachariah R, Lawn SD, Rosen S. Strategies to improve patient retention on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):70–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Howard AA, El-Sadr WM. Integration of tuberculosis and HIV services in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S238–44. doi: 10.1086/651497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Matsubayashi T, Manabe YC, Etonu A, Kyegombe N, Muganzi A, Coutinho A, et al. The effects of an HIV project on HIV and non-HIV services at local government clinics in urban Kampala. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Shigayeva A, Atun R, McKee M, Coker R. Health systems, communicable diseases and integration. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(Suppl 1):i4–20. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Greig J, O’Brien D, Ford N, Spelman T, Sabapathy K, Shanks L. Reduced mortality and loss to follow-up in integrated compared with vertical programmes providing antiretroviral treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. JAIDS. 2012;59(5):92–98. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824206c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.WHO. Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cherutich P, Kaiser R, Galbraith J, Williamson J, Shiraishi RW, Ngare C, et al. Lack of knowledge of HIV status a major barrier to HIV prevention, care and treatment efforts in Kenya: results from a nationally representative study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Druyts E, Dybul M, Kanters S, Nachega J, Birungi J, Ford N, et al. Male gender and the risk of mortality among individuals enrolled in antiretroviral treatment programs in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2012 Aug 31; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359b89b. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]