INTRODUCTION

Is history important? My answer is, “Yes, history is very important.” Physicians understand very clearly that the past matters. We ask very detailed questions about our patients’ medical history, trying to reconstruct an accurate picture of their state of health. We know that health is heavily influenced by the past: heredity, past behaviors, past experiences, and past diseases. These data give us clues to our patients′ present health condition. We make notes about the patients′ status and file these notes. On the patient's next visit, we pull out that patient's file which contains all the notes from past visits. The patient's past medical status gives us important perspective on the patient's present condition. We plan and approach our management strategies based on our perspective of the patient.

The past helps us understand the present. Such outlook is important in medicine as it helps us develop strategies to solve current problems and advance the cause of medicine. Human diseases evolve throughout the ages and it is both interesting and enlightening to be aware of the evolution in our understanding of a particular disease and see how the ancients managed it. Through history, we learn of man's battles against disease. His victories formed the basis of our profession. We also learn about quacks, witch doctors, magic, and superstition. The important discoveries in our profession such as antisepsis, antibiotics, anesthesia, and the triumphs and failures of great scientists are compelling. Indeed, the history of medicine is a fascinating history.

A WINDOW IN THE SKULL

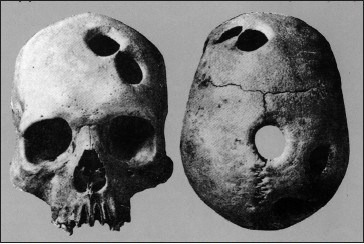

In prehistory, people believed that pain and disease originated from evil spirits. Disease resulted when these evil spirits entered the body. Witch doctors and shamans were employed to exorcise wicked beings; if they failed there was an operation that might do the trick: trepanation - one of the very few prehistoric medical practices for which we have archaeological evidence. The practice involved cutting a small hole in the skull. The procedure was used to treat headaches, skull fractures, epilepsy, and some forms of mental illness, and it was employed worldwide since archaeology has uncovered trepanned skulls in Europe, North Africa, Asia, Tahiti, New Zealand, and South America. Trepanation was particularly popular in ancient Peru where skulls have been found with as many as five trepanned holes. Those who survived the operation (and some did, as evidenced by healed skulls that have been discovered) had their wounds covered with a piece of gourd, stone, shell, or even silver and gold. In Europe, the excised rounds of skull bone were worn as amulets.

Peruvian skull showing four holes, two over the left frontal and two on top of the skull on the right, seen from the back. Experts believe all the wounds had healed eventually

Trepanation was practiced in Europe up to the 16th century; oil painting by Hieronymous Bosch, c. 1494, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Trepanation lasted well into the middle ages. Today, the practice is taken up by a few audacious people who swear by its ability to expand consciousness.

A 3000-year-old Egyptian mummy

MUMMY POWDER THERAPY

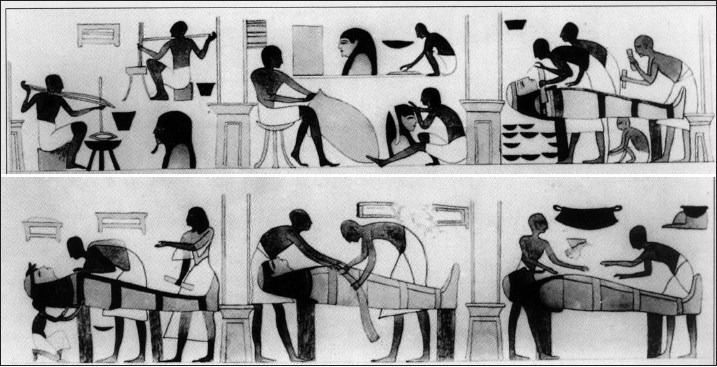

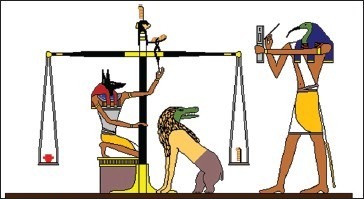

Bound in fragile linen wrappings, a mummy is an enduring fixture in classic horror movies. This is understandable because in a way, mummies are real-life tangible ghosts. They are bodies that stick around long after death. In the past 200 years, scientists have discovered ancient mummies in diverse locales around the world, but the practice of mummification is thought to have originated in ancient Egypt. The internal organs in the abdomen and chest and the brain were removed except the heart which was usually left in place. The heart was important to the ancient Egyptians as they considered the heart the seat of intelligence and of life itself. In the final judgment portrayed in The Book of the Dead, the heart of the deceased is shown being weighed against the feather of Ma′at, a symbol of universal truth, harmony, and balance. Their ancient beliefs remain with us today within the very fiber of our emotions, our poetry, and our song lyrics. When we refer to our hearts in regard to love or any other emotion, we are invoking a living memory of the ancient Egyptian belief system. Although the ancient Egyptians realized the importance of the heart, they did not understand the circulation of the blood.

Mummification had a profound but indirect effect on the growth of medical science. It made the Egyptians familiar with the idea of cutting up corpses, and so encouraged an atmosphere of research. Eventually, the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt (320-30 BC) gave their Greek physicians permission to study the human body systematically by dissection.

Egyptian wall painting illustrating the process of mummification: internal organs were removed including the brain, but the heart was left in place after which the body was placed in a mound of dry natron, a natural compound rich in common salt and sodium bicarbonate. The natron soaked up the fluids of the body before it was cleaned and bandaged

Weighing the heart in ancient Egypt. In the Book of the Dead, the heart was weighed against the feather Ma’at, the goddess of justice.

Many centuries later, an Alexandrian Jew named Elmagar is said to have treated patients with “mummy” - a powder made from ground up portions of embalmed cadavers. This “therapy” was also used by Guy de Chauliac, surgeon to Pope Clement VI, in the 14th century. “Mummy” was highly regarded until the early 16th century. Francois I of France used to carry a little packet of it, mixed with powdered rhubarb, in case of accident, since it was thought to be good for bruises and wounds; it was also taken internally for various ailments.

Mummification occurred sporadically over the centuries. Some of the Egyptians’ techniques were used to preserve the bodies of Henri IV and Louis XIV of France. It reached its apotheosis in 1852, with the embalming of Alexander, tenth Duke of Hamilton. An Egyptian ceremony was carried out, with TJ Pettigrew, the first Professor of Anatomy at Charing Cross Hospital, London, as embalmer and chief ritualist. The body was laid to rest in an ancient Egyptian sarcophagus that had originally been intended for the British Museum.

Today, Egypt's mummies tell us much about the ancient Egyptians themselves. Modern paleopathologists have discovered that they suffered from bladder and kidney stones, gallstones, schistosomiasis (bilharzia), arterial disease, gout, appendicitis, mastoid disease, and a great many illnesses of the eye. Many skeletons had evidence of rheumatoid arthritis. The earliest mention of arthritis in the history of man dates back millions of years. Archaeologists and paleopathologists record that prehistoric man was “often malformed, racked with arthritis and lamed by injuries.” One way of treating the affliction was through the power of divination or foretelling the future.

Interestingly, dental decay was rare, usually only appearing in the wealthy. So far, no evidence of such diseases as rickets and syphilis has been found.

EDWIN SMITH SURGICAL PAPYRUS

Egyptian medicine was a mixture of magical and religious spells and any attempt to impose the modern distinction between magic and medicine only confuses the picture. The most common cure for maladies was probably the amulet or magic spell rather than medical prescriptions alone since many illnesses tended to be regarded as the result of malignant influences or incorrect behavior. However, as early as 2686-2613 BC, there were already individuals corresponding roughly to the modern concept of doctor, for whom the term sinw was used. There were also surgeons called “priests of Sekhmet” as well as the ancient equivalent of dental and veterinary practitioners.

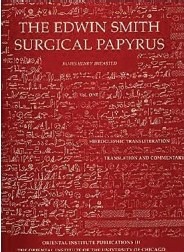

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an Ancient Egyptian medical text on surgical trauma, c. 1600 BC. It is unique among the medical papyri that survive today because it presents a rational and scientific approach to medicine in Ancient Egypt, unlike other papyri which are based on magic

There are about 10 ancient medical papyri that have been found and all contain major information that help us study medical practices in ancient times, but remedies have also been found on pieces of pottery and ostraca (pieces of broken pots or stones inscribed with writing or illustration of daily life; the ancients used them as writing material, pretty much like papyrus or parchment) dating from the Amarna period to the time of Roman occupation. The most famous and most important is the Edwin Smith Papyrus which presents a rational and scientific approach to medicine in ancient Egypt, unlike the other papyri such as the Ebers Papyrus and London Medical Papyrus which are medical texts based on magic.

The Edwin Surgical Papyrus (c. 1600 BC), written in Egyptian hieratic script, was once thought to be the work of a military surgeon, but recent opinion suggests that its author may have been a doctor associated with pyramid-building workforce. The text deals mainly with such problems as broken bones, dislocations, and crushings. It has 48 cases, which are typical rather than individual. The papyrus begins by addressing injuries to the head, and continues with treatments for injuries to neck, arms, and torso, detailing injuries in descending anatomical order. The title of each case details the nature of trauma, such as “Practices for a gaping wound in his head, which has penetrated to the bone and split the skull.” The objective examination process included visual and olfactory clues, palpation, and taking of the pulse. Following the examination are the diagnosis and prognosis, where the physician judges the patient's chances of survival and makes one of three diagnoses: “An ailment which I will treat,” “An ailment with which I will contend,” or “An ailment not to be treated.”

The Code of Hammurabi is the most complete legal compendium in antiquity. It is a useful source on ancient Babylonian culture and justice, including medical practice. It set out for the first time the concept of civil and criminal liability for improper and negligent medical care. It is made of black basalt, 8 feet high, covered in cuneiform script, and on display in the Louvre Museum, Paris

Among the treatments in the papyrus are closing wounds with sutures (for wounds of the lip, throat, and shoulder), bandaging, splints, poultices, preventing and curing infection with honey, and stopping bleeding with raw meat. Immobilization is advised for head and spinal cord injuries, as well as other lower body fractures. The papyrus also describes realistic anatomical, physiological, and pathological observations. It contains the first known descriptions of the cranial structures, the meninges, the external surface of the brain, the cerebrospinal fluid, and the intracranial pulsations. In this text, the word "brain" appears for the first time in any language.

The procedures of this papyrus demonstrate an Egyptian level of knowledge of medicines that surpassed that of Hippocrates, who lived 1000 years later. The influence of brain injuries on parts of the body is recognized, such as paralysis. The relationship between the location of a cranial injury and the side of the body affected is also recorded, while crushing injuries of vertebrae were noted to impair motor and sensory functions. Due to its practical nature and the types of trauma investigated, it is believed that the papyrus served as a textbook for the trauma that resulted from military battles.

Although it cannot be claimed that the writer understood the concept of the circulation of the blood, the author of the papyrus clearly recognized that the condition of the heart could be judged by the pulse:

“The counting of anything with fingers [is done] to recognize the way the heart goes. There are vessels in it leading to every part of the body ... When a Sekhmet priest, any sinw doctor ... puts his fingers to his head ... to the two hands, to the place of the heart ... it speaks ... in every part of the body.“

Experts say the Edwin Smith Papyrus dates to Dynasties 16–17 of the Second Intermediate Period. Egypt was ruled from Thebes during this time and the papyrus is likely to have originated from there. The first translation of the papyrus was by James Henry Breasted in 1930. Breasted's translation changed the understanding of the history of medicine. It demonstrates that Egyptian medical care was not limited to the magical modes of healing demonstrated in other Egyptian medical sources. Rational, scientific practices were used, constructed through observation and examination.

MEDICINE REGULATED BY LAW

The Babylonians were the first to regulate medicine by law. These laws regulating medicine are inscribed in cuneiform script on a polished black diorite stone called Hammurabi's Law Code because the upper part of the pillar shows King Hammurabi (c. 1695 BC) receiving the commission to write his laws from Shamash, the Babylonian sun god and god of justice. Below this figure are 282 laws dealing with social structure, economic conditions, industries, family life, and medical practice. Seventeen laws tell what a physician should be paid for certain types of work and what his responsibilities were. For example, the Hammurabi Code specifies that: “If a physician has performed a major operation on a lord with a bronze lancet and has saved the lord's life ... he shall receive ten shekels of silver.” The work was well-paid: ten shekels equaled a carpenter's income at the time for 450 working days! Saving the life of a commoner was only worth five shekels and that of a slave, two. The job may have paid well, but there were certainly high risks: “If a physician performed a major operation on a lord ... and has caused the lord's death ... they shall cut off his hand.”

These laws only dealt with surgery; bad results from drugs or incantations were not subject to penalty. This was in keeping with Babylonian beliefs: if people became ill, it was their own fault, because they had sinned or had allowed a bad spirit to invade them; but if a physician made a deliberate surgical wound and the outcome was death, that was the physician's responsibility.

The Code of Hammurabi is fascinating and is a useful source on ancient Babylonian culture and justice. It indicates that Babylonian society was an organized society with a rigid class-structure. The code is a series of practical laws that extended to shaping the society's way of life. The Code of Hammurabi is significant in terms of outlining the duty of doctors. It covered the topic of medical practice and set out for the first time the concept of civil and criminal liability for improper and negligent medical care.

Hammurabi's Code stands 8 feet high in the Department of Near Eastern Antiquities, in the Louvre Museum in Paris. It was discovered in 1901 by laborers at an excavation in Khuzestan, Iran (ancient Susa, Elam). The basalt stele was erected in 1800 BC by Hammurabi, king of Babylon, and is considered a work of art, history, and literature. It is the most complete legal compendium of antiquity, dating back to earlier than the biblical laws. It was among the items plundered and carried to Susa by an Elamite prince in Iran in the 12 th century BC. It is a beautiful and impressive block of black basalt, meticulously polished. When it was discovered, it was broken into three pieces but otherwise hardly damaged. The Louvre refers to it as “the emblem of Mesopotamian civilization.”

ANCIENT CHINA

The Nei Ching (Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine) was supposedly compiled between 479 and 300 BC and is the source of information on China's early medicine. It takes the form of a conversation between the “golden emperor” Huang Ti, who is supposed to have lived between 2629 and 2598 BC, and his Prime Minister Ch′i Po and deals almost exclusively with acupuncture. Human dissection was strictly forbidden in ancient China and physicians knew very little about anatomy. The Nei Ching also describes the 12 pulses to be palpated by the physician, six in each wrist. The multitude of qualities that each one could have is poetically described, for example: smooth as a flowing stream; dead as a rock; like water dripping through the roof; light as flicking the skin with a plume. The Chinese have an extensive pharmacy of some 2000 items and 16,000 remedies, not all herbal, many of them strange and even repulsive from a Western viewpoint. Patients were given pulverized seahorses for goiter, snakemeat for eye ailments, octopus ink mixed with vinegar for heart disease, and elephant skin for persistent sores.

The Nei Ching or Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine is the source of information on China's early medicine

The West knows of only one surgeon of prominence from Ancient China: Hua T′o who is thought to have lived 1800 years ago. His story has come down to us under the title, The Surgeon and the General. One of his patients was the warlord Kuan Yun. When Kuan's arm was pierced by a poisoned arrow, Hua cut and scraped out the wound down to the bone, while the warlord played chess and drank cups of wine. History, however, does not record whether he had the benefit of acupuncture anesthesia!

Hua believed himself above politics and when Kuan's bitterest enemy, Tsao Tsao, came to him with a bad headache, Hua decided to treat it by trepanation. Just as he was about to begin, Tsao suddenly got the notion that Hua might have been bribed by Kuan to murder him and had the unfortunate surgeon executed on the spot!

ANCIENT INDIA

The origin of the Indian system of medicine is known as Ayurveda, literally, knowledge or science of life. Few written records survive, but the four Vedas, sacred Sanskrit books that were passed down orally through the ages, are all that is left. Ayurvedic medicine was wrapped up in religion and physicians used incantations and watched from portents as often as they administered drugs and operated. Like the Chinese acupuncture points, they identified points in the body considered crucial to health, called marmas. If a person were wounded in one of these marmas, the outcome was likely to be fatal since some of them corresponded to major arteries, nerves, and tendons. Indian physicians also believed that disturbances in the levels of various substances such as wind, bile, phlegm, and blood were responsible for disease, similar to the Greek Four Humor theory of disease. It is theorized that the concept was picked up by travelers and transplanted to Greece. The Indians excelled in surgery. They had several different steel instruments: scalpels, probes, trocars, catheters to carry out different procedures: cautery, sewing up wounds, draining fluid, treating cataracts, removing bladder and kidney stones and, most remarkable, repairing noses and earlobes with plastic surgery. The amputation of body parts was a common punishment in ancient India, and quite often it was the culprit's nose that was singled out for attention.

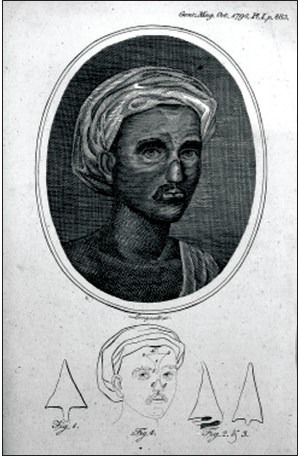

Nose Reconstruction was developed in India by the Hindu surgeon Susrata in 500 BC. The technique of rhinoplasty is widely practiced by plastic surgeons today

With plenty of opportunities for practice and experiment, probably based on trial and error, the Ayurvedic doctors came up with a new technique leading to the earliest recorded nose restorations. It was developed in India by the Hindu surgeon Susrata in about 500 BC. He used a flap of skin from the forehead, called a pedicle, to form a new nose. The forehead reconstruction method developed by Susrata was translated into Arabic in the 7th century and into English in the 1700s.

The technique of rhinoplasty is widely practiced by plastic surgeons today. Rhinoplasty changed from a procedure to construct a nose lost through punishment or accident to one in which the size or shape of the nose is changed. It was first used for cosmetic purposes in 1898, when a surgeon operated on a young man whose nose caused him such embarrassment that he was unable to leave the house. The “nose job,” as rhinoplasty is also known, became common among Hollywood actors and actresses from the 1930s. Nowadays, many people have rhinoplasty in order to conform to contemporary ideals of beauty and it has raised concerns that people feel forced to adhere to a constructed notion of beauty in order to bolster their self-esteem.

ANCIENT GREECE AND THE FOUR HUMORS

With the rise of Greek civilization, diseases were no longer blamed on the gods and sin, but on imbalance within the body itself, giving rise to the theory of the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. The Greeks thought that when the balance between the four humors was disturbed, the result was disease.

Physicians in ancient Greece were usually itinerant. Although not landowners or having high social standing, clearly they were considered men of some importance. They took detailed medical histories and observed patients closely, looking for things within people's lives and surroundings that might have a bearing on their health. They dressed wounds with herbal/mineral mixtures and with wine and vinegar, all of which had antiseptic properties. They treated ailments with purgatives and blood-letting, therapeutic approaches that lasted for 2000 years. They also employed tourniquets and auscultation, pressing an ear against the chest. Doctors believed that they were servants of the sick and not mediators between the gods and humanity.

The four humors theory: Disease resulted when the balance between the four humors was disturbed, a concept prevalent in ancient Greece

The most well-known of all the physicians of ancient Greece was Hippocrates (c. 400 BC). His works and that of his followers are contained in the Hippocratic Corpus, over 70 volumes that range from detailed case histories to thoughts on the practice of medicine, the role of environment in health, and prognoses. Attempts to prognosticate or predict the outcome of an illness set apart followers of the Hippocratic School from those of other medical schools of thought who only elicited symptoms and tried to diagnose. Patients found it reassuring and comforting to be told the expected outcome of their illness. It is a medical technique that physicians of today still employ. Many of the medical techniques of classical Greece were lost with the passing of the Greek civilization.

The Greek physicians recognized the spiritual side of healing. If their therapeutic management was not working, the patients were directed to attend one of their many asklepieia - temples to the patron god of medicine, Asklepios, and his daughters Hygeia (health) and Panacea (healing). Asklepios would often be accompanied by a snake, the drakon, hence the medical symbol of a snake wound round a staff. Pilgrims to the temples relaxed among the beautiful surroundings and read inscriptions on marble pillars that described the miraculous cures performed by the god. Then they would bed down for the night in the sacred hall, where Asklepios would supposedly appear as they slept, to give them a “dream drug” or even to perform “dream surgery.”

The Greeks established schools of medicine in Rome, all influenced by the Hippocratic Corpus. In the early days of Rome, however, Roman medicine consisted of pacifying the gods and reliance on traditional folk medicine. According to the historian Livy, in 293 BC, a plague ravaged Rome and the city sought help from the Greek god Asklepios (Roman Aesculapius). A ship was sent to Greece, and the god came aboard in the form of a snake. Approaching Rome, the snake swam to an island in the Tiber. A temple was erected there and the plague disappeared. This marked the beginning of Greek influence on Roman medicine. Eventually, healing came to be entirely in Greeks’ hands and remained so for centuries.

STATUS OF PHYSICIANS IN ANCIENT ROME

When in 46 BC, Julius Caesar granted citizenship to all foreigners teaching a liberal art in Rome, physicians were included. At that time, most physicians were slaves or freed men. When Antonius Musa, once Mark Antony's slave, cured Emperor Augustus of a serious illness by cold hydrotherapy in 23 BC, he was richly rewarded and won immunity from taxation for all physicians. In Rome, physicians were either independent practitioners or physicians attached to a particular family or the emperor or public physicians (archiatri, i.e. paid by a town to look after its citizens).

Training as a physician was difficult to obtain, apprentices being dependent for learning on physicians to whom they were attached. Only the well-off could afford to travel to different medical centers such as Alexandria and Ephesus to obtain a well-rounded education. Medical texts were expensive or inaccessible. However, guilds often purchased texts for the benefit of its members, and medical books were also sent to all military forts, hence spreading medical knowledge to every corner of the empire.

The common people, however, believed physicians spent their time theorizing and arguing among themselves, sometimes killing their patients with promised cures and then asking for payment from relatives. Medicine's bad image was reflected in literature. The historian Pliny wrote: “There is no doubt that all these [physicians], in their hunt for popularity by means of some novelty, do not hesitate to buy it with our lives ....” Hence, that gloomy inscription on monuments: “It was the crowd of physicians that killed me.”

Asclepieion or healing temple model in ancient Greece, sacred to Asklepios, the god of medicine. A healing temple is a religious temple devoted toward Faith Healing. Asklepios is said to come to the patients in a dream accompanied by a snake, hence the medical symbol of a snake wound round a staff

PAST GLORIES: ALEXANDRIA IN ANTIQUITY AND HUMAN DISSECTION

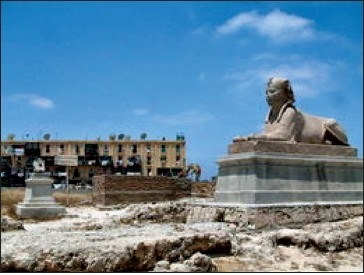

Alexandria, Egypt, is an important city in the history of medicine. There, King Ptolemy, who ruled Egypt from 323 to 282 BC, established the Alexandrian Museum and the Great Library of Alexandria, fabled in antiquity for its treasures of wisdom. Radical new thinking and understanding of disease processes came out from the fertile intellectual and scientific climate prevailing in Alexandra from the 3rd century BC to the 7th century AD. Alexandria became world-renowned as a great center of Greek learning.

The intellectual and scientific ferment taking place in Alexandria attracted medical talent. Both the medical school and the medical research in Alexandria were the most famous in antiquity. At Alexandria, dissection of corpses was permitted and was a regular practice for the first time in history.

The two outstanding medical investigators in Alexandria were Herophilus (c. 330-260 BC) and Erasistratus (c. 304-250 BC). They were the two leading professors of the “new medicine” that sprouted and flowered in Alexandria. In contrast to the physical observations and disease descriptions of the Hippocratic School, Herophilus was concerned with direct knowledge and precise terminology. In order to achieve this, Herophilus embarked upon a new study of the human body, based on anatomy and human dissection. Tertullian, a prolific early Christian author in Rome, indignantly denounced Herophilus’ pioneer work: “Herophilus the physician or that butcher who cut up hundreds of human beings so that he could study nature”.

Alexandria, Egypt

Herophilus was a Greek physician and was the first to base his writings on authorized, legitimate dissection of the human body. He recorded his observations in On Dissections. His contemporary, Erasistratus, is also best known for his work on human cadavers and his knowledge of the human body. Erasistratus is considered the father of physiology.

The medical school in Alexandria was in the forefront in the move toward a "scientific" medicine. The contributions of Herophilus to our knowledge of anatomy and medical terminology are enormous. Through his anatomical studies on the nervous system, Herophilus proved that the brain and not the heart was the seat of intelligence, a revolutionary breakthrough for that period since it contradicted a prevailing Aristotelian concept which stated that the heart is the seat of intelligence, rational thoughts, emotions, and desires. Unfortunately, their writings have been lost and most of our knowledge of these two is derived from commentators, especially Celsus and Galen.

GALEN'S SHADOW

Ancient philosophers were obsessed about the nature of the human soul – the life-principle or substance of every living being; in other words, the spirit: where is it located? In the heart? In the brain? What is the function of each organ? Through observation and experimentation, they struggled to sort out which organ was responsible for what function.

Where is the center of emotions and feelings? Where is the seat of intelligence? These issues were a source of confusion in ancient times. Traces of such confusion live on in the tradition of metaphorically describing feelings and emotions as if they actually originated from the heart. This tradition has enriched our language and literary heritage. The Babylonians thought that the liver was the most important organ of the body because it was used for divination, which was an integral part of their daily life. Hence, the liver was thought of as the center of feelings and emotions; the heart was the center of the mind; the stomach was the center of strength and courage; and the uterus was the center of motherly love.

The ancient Egyptians cited the heart as the center of feelings and emotions, which later Greek and Arab physicians adapted. Aristotle believed in it, and so did Galen (c. 130-200 A.D.). There was even a time when it was believed that the heart was the center of thoughts and reasoning until Herophilus, as a result of his anatomical studies on the nervous system, proved that the brain and not the heart was the seat of intelligence. Galen believed in Aristotle and Herophilus. Galen, in his writings, appreciated and admired the work of Herophilus: “his knowledge of facts acquired through anatomy was exceedingly precise, and most of his observations were made not, as in the case of most of us, on brute beasts but on human beings themselves.” Galen believed that dissection was essential to medical understanding.

Galen is a giant in the history of medicine and casts a long shadow. His medical theories dominated European medicine for 1500 years. He was a Greek physician who practiced in Rome, becoming physician to five Roman emperors. He was prolific and wrote hundreds of treatises, compiling all significant Greek and Roman medical thoughts, and adding his own discoveries and theories, foremost of which was the humoral basis of disease: illness was caused by an imbalance of the four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. He showed, through experimentation, that the arteries carried blood, and not air, as was commonly believed. He almost discovered the circulation, but failed to make the correct deductions from the data available to him.

Galen's writings contained many erroneous descriptions of human anatomy because he performed dissections on apes and extrapolated his findings to humans. Yet, he did not illustrate his findings and observations. It is possible that the errors might have been picked up earlier and rectified by subsequent investigators had there been drawings and sketches to accompany the voluminous written texts. Had that been the case, one wonders what advances, what leaps we would have made in our current understanding of the heart. Where would we be now? It is a tantalizing thought.

No doubt, Galen was a prolific and brilliant physician who expounded extensively on anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, pathology, therapy, hygiene, dietetics, and philosophy, but the judgment of many historical writers is that he was an arrogant and unpleasant man, who used his learning and verbal skills to bash opponents into submission. He mocked and ridiculed opinions contrary to his own, whether contemporary or earlier. When he left Rome abruptly in AD 166 to spend 3 years in Pergamum, he claimed it was because he feared assassination by rivals. He had no friends. He reportedly said: “Whoever seeks fame need only become familiar with all that I have achieved.”

FOR FURTHER READING

Sutcliffe J, Duin N. A history of medicine. New York: Barnes and Noble, Inc., 1992.

Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Smith_Papyrus [Last accessed on 2012 September 17].

Available from: http://www.cliojournal.wikispaces.com/Hammurabi′s+Code [Last accessed on 2012 September 17].

Available from: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/law-code-hammurabi-king-babylon [Last accessed on 2012 September 17].

Available from: http://www.musee.louvre.fr/oal/code/indexEN.html [Last accessed on 2012 September 17].

Hajar R. Medical illustration: Art in medical education. Heart Views 2011;12:83-91.

Lyons AS, Petrucelli RJ. Medicine an illustrated history. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987.

Hajar R. Past glories: The great library of alexandria. Heart Views 2000;1:278-82.