Abstract

Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) is a hydrolytic enzyme with wide range of substrates, and capability to protect against lipid oxidation. Despite of the large number of compounds that can be hydrolyzed by paraoxonase, the biologically relevant substrates are still not clearly determined. There is a massive in vitro and in vivo data to demonstrate the beneficial effects of PON1 in several atherosclerosis-related processes. The enzyme is primarily expressed in liver; however, it is also localized in other tissues. PON1 attracted significant interest as a protein that is responsible for the most of antioxidant properties of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Several bioactive molecules such as dietary polyphenols, aspirin and its hydrolysis product salicylate, are known to stimulate PON1 transcription activation in mouse liver and HepG2 cell line. Studies on the activity, function, and genetic makeup have revealed a protective role of PON1. Some striking data were obtained in PON1 gene knockout and PON1 transgenic mouse models and in human studies. The goal of this review is to assess the current understanding of PON1 expression, enzymatic and antioxidant activity, and its atheroprotective effects. Results from in vivo and in vitro basic studies; and from human studies on the association of PON1 with coronary artery disease (CAD) and ischemic stroke will be discussed.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Atherosclerosis, Cardiovascular disease, Coronary artery disease, PON1

PON1 Enzymatic Activity and Antioxidant Effects

Paraoxonases were originally discovered as enzymes hydrolyzing exogenous toxic organophosphate compounds such as insecticide paraoxon. There are three members of paraoxonases family currently known: Paraoxonase 1 (PON1), Paraoxonase 2 (PON2), and Paraoxonase 3 (PON3), which are encoded by three separate genes on the same chromosome 7 (human) or chromosome 6 (mouse). PON1 protein consists of 354 amino acids with molecular mass 43 kDa.[1] All three human members of the family are 70% identical at nucleotide level and 60% identical at the amino acid level.[2]

Studies on enzymatic activity of paraoxonases revealed esterase and lactonase/lactonizing activities in addition to organophosphatase activity.[3,4] Despite of the large number of compounds that can be hydrolyzed by paraoxonase, the biologically relevant substrates are still not determined for certain. In many cases arylesterase activity is measured to access PON1 level in biological samples. Based on kinetic parameters of paraoxonases toward different substrates, it is assumed that lactones are the likely physiological substrates.[4] Hydrolysis of homocysteine thiolactone by PON1 is considered to be protective against coronary artery disease (CAD).[5]

After the introduction of the oxidative stress hypothesis of atherosclerosis and the discovery of antioxidant effect of high-density lipoprotein (HDL),[6,7] PON1 attracted significant interest as a protein that is responsible for the most of antioxidant properties of HDL.[8] Purified PON1 protects HDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) from oxidation catalyzed by copper ions.[9,10] PON1 inhibits copper-induced HDL oxidation by prolonging oxidation lag phase, and reduces peroxide and aldehyde content in oxidized HDL. Remarkably, PON1 inhibitors PD-11612, PD-65950, PD-92770, and PD-113487 lessen this antioxidative effect of PON1. Incubation of purified PON1 with hydrogen peroxide or lipid peroxides partly decomposes them. PON1 is especially effective in decomposition of linoleate hydroperoxides.[9] Also, mass-spectrometry analysis of biologically active fraction of oxidized2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine (Ox-PAPC) underwent PON1 treatment showed degradation of these oxidized phospholipids by PON1.[11]

The exact antioxidant mechanism of PON1 is not known yet, although it is known that protection is not caused by chelating of copper ions or because of potential lipid transfer from LDL to HDL. Existence of an enzymatic mechanism is supported by the observation that heat inactivation of purified PON1 abolishes its antioxidant effect.[10]

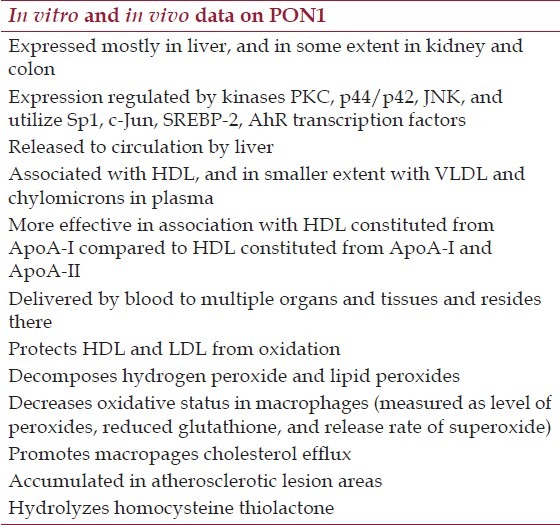

Some in vitro data suggest that antioxidant activity might be related to other components of purified PON1 preparations.[3,12] However, experiments with PON1 deficient mouse provide strong evidences that PON1 is required to enable HDL antioxidant properties. HDL from PON1 knockout animals were more prone to oxidation and were less efficient in the protection of LDL from oxidation in co-cultured cell model of the artery wall compared with HDL from control mice.[13] Also, transfection of PON1-deficient peritoneal macrophages (isolated from PON1 knockout mice) with human PON1 decreased level of peroxides, lowered release of superoxide, and increased intracellular level of reduced glutathione, key observations are summarized in Table 1.[14]

Table 1.

Summary of key facts on PON1 expression, activity, and effects in in vitro and in vivo studies

PON1 Expression and Tissue Distribution

Liver is the principal tissue for PON1 gene expression. The first PON1 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA)ionanalysis in different rabbit tissues was performed by northern blot, and revealed PON1 mRNA expression predominately in liver.[15] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using a panel of first-strand complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNAs) from 24 tissues detected PON1 expression in kidney and colon beside liver and fetal liver expression.[16] Biopsies showed PON1 mRNA and protein expression in human but not in mouse gastrointestinal tract.[17] Deletion analysis in cultured cells revealed that cell type specific expression in liver and kidney is determined within first 200 bp of promoter area.[18]

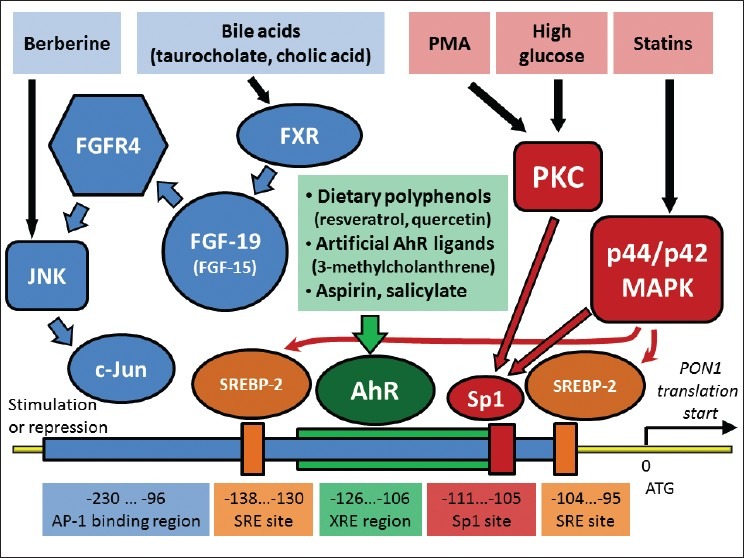

There are several transcription factors and pathways that regulate PON1 expression [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Pathways and transcription factors that involved in transcriptional regulation of PON1 expression in liver. All processes occur in liver, and bile acid -stimulated synthesis of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF-19; or FGF-15 in mouse) might be additionally occur in ileum. Positions of regulatory elements are shown based on PON1 gene in human. Arrows represent activation effect. Signals from PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) and high glucose activate transcription factor Sp1 through protein kinases C (PKC) and p44/ p42 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK)

A ubiquitous mammalian transcription factor Specificity Protein 1(Sp1) plays an essential role in regulation of PON1 expression. High glucose level activates protein kinase C (PKC), which activates Sp1, and stimulate PON1 transcription in human hepatoma cell lines HepG2 and HuH7.[19] A potent PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) also stimulates PON1 transcription in HepG2 through activation of Sp1. Two members of PKC family are involved, PKCζ (zeta) and PKC-α (alpha) activation. PKCζ (zeta) mediates transcriptional upregulation PON1 in HepG2 in response to insulin.[20] Statins (pitavastatin, simvastatin, or atorvastatin) stimulate PON1 transcription through Sp1 activation as well, however, they activate another kinase, p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, as was observed for pitavastatin in HuH7 cells.[21,22] Also, pivostatin-stimulated p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activates sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP-2), which contributes to transcriptional activation of PON1. Simvastatin activates SREBP-2 and upregulates PON1 as well.[22,23]

Dietary polyphenols, such as resveratrol, aspirin and its hydrolysis product salicylate, and artificial ligands of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), such as 3-methylcholanthrene, activate AhR and stimulate PON1 transcription activation in mouse liver and HepG2 cell line.[24–26] c-Jun is another transcription factors that is involved in PON1 expression. The activity of c-Jun is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). Phosphorylated c-Jun in a complex with c-Fos or some other transcription factors forms an active AP-1 complex that usually promotes transcription of target genes. Thus, berberine (benzyl tetrahydroxyquinoline), a cholesterol lowering alkaloid, activates JNK, c-Jun and stimulates PON1 transcription in human hepatoma cell lines.[27] However, stimulation of JNK/c-Jun pathway by bile acids leads to opposite effect. Bile acids such as taurocholate, cholic acid, or chenodeoxycholic acid inhibit PON1 expression in liver of C57BL/6J mice, and in HepG2 and HuH7. The inhibition of PON1 expression starts with activation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) by bile acids that promote expression of fibroblast growth factor 19 in human (FGF-19) or FGF-15 in mouse. The growth factor activates fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) followed by activation of JNK, and phosphorylation of c-Jun. Opposite to activation of c-Jun by berberine, FXR/FGF-19/FGFR4/JNK/c-Jun pathway results in suppression of PON1 transcription. FXR and FGFR4 are absolutely necessary for the pathway. Bile acids do not inhibit PON1 expression in FXR-/- and FGFR4-/- mice.[28,29]

Paraoxonase activity in human liver is primarily localized in microsomal fraction.[30] It is likely that PON1 stays associated with endoplasmic reticulum through its hydrophobic N-terminus until it is released from the hepatocytes. The mechanism of PON1 secretion is not well investigated. A study on cultured hepatocytes and transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, which do not naturally express PON1 and ApoA proteins, shed some light on releasing of PON1 from the cells. When PON1 protein is synthesized, it accumulates on plasma membrane and slowly dissociate into extracellular medium. Dissociation is promoted by HDL, very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and in much lesser extent by protein-free phospholipids particles or ApoA-I protein. LDL does not promote PON1 release from the cells.[31,32]

PON1 binds to HDL through interaction of hydrophobic N-terminus to phospholipids, and through PON1-ApoA interaction.[33] ApoA protein composition of HDL is essential for binding to PON1 protein. Two major principal HDL proteins, that is, ApoA-I and/or ApoA-II which differ in their properties are linked to atherosclerosis modulation. Thus, transgenic mice with HDL consisting of both human ApoA-I and ApoA-II developed 15-fold greater lesions compared with mice with HDL containing solely human ApoA-I.[34] In vitro study of reconstituted HDL demonstrated that ApoA-I containing HDL stabilizes PON1 binding as compared with protein-free HDL particles, and ApoA-II in opposite destabilizes the HDL–PON1 complex. The paraoxonase and arylesterase activities of PON1 do not depend on the apolipoprotein content of HDL. However, ApoA-I containing HDL significantly increases lactonase activity of PON1, promotes inhibition of LDL oxidation, and stimulates macrophage cholesterol efflux compared with ApoA-II containing HDL.[35,36] A study of human HDL isolated from ApoA-I deficient patients revealed that PON1 is still associated with HDL in the absence of ApoA-1, however, the PON1–HDL complex is less stable, and PON1 loses activity faster than in normal controls.[37]

Similar effects of ApoA protein composition in HDL were observed in transgenic animal studies. A higher content of human ApoA-II protein in mouse HDL suppresses PON1 binding to HDL compared with HDL with lower human ApoA-II content. HDL high in human ApoA-II binds less PON1 protein, possesses less PON1 activity, and is impaired in protection of LDL from oxidation. Transgenic mouse with higher human ApoA-II content in HDL are more susceptible to atherosclerosis compared with transgenic animals with lower ApoA-II level in HDL and control animal.[34,38,39]

HDL facilitates distribution of PON1 protein through the body. HDL-associated PON1 can be successfully transferred to cultured cells in vitro and deliver protection from oxidative stress and bacterial substrate of PON1 N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl-L-Homoserine lactone.[40] Beside HDL, some amount of PON1 in human plasma is associated with VLDL and chylomicrons.[41]

While liver is the major tissue of PON1 gene expression, lipoprotein-assisted circulation of PON1 in plasma delivers the enzyme to multiple tissues that do not express PON1 themselves. Immunohistochemical staining of rat tissues revealed PON1 presence in liver, kidney, in endothelial lining of lung and brain.[42] More recent study with mouse tissue detected PON1 protein in hepatocytes, adipocytes, chondrocytes, skeletal and cardiac muscle, kidney, spermatozoa, and epithelial cells of skin, stomach, intestine, trachea, bronchiole, and eye lens. Studies did not find co-localization of PON1 with ApoA-I protein that might mean local PON1 expression or different sources of ApoA-I, an integral component of HDL.[43]

Immunostaining of healthy human aorta shows a low level and granular distribution of PON1 in smooth muscle cells. Western blot confirmed presence of intact and degraded PON1 in media of healthy aorta. With the development of atherosclerosis, PON1 staining of media increases and becomes homogeneous. Increasing accumulation of PON1 with the progression of the atherosclerosis can be seen in the intimal part of aorta as well. Aorta with advanced atherosclerosis lesions shows massive PON1 accumulation.[44] A more recent study attributed an increased PON1 immunostaining in human atherosclerotic arteries to macrophages accumulated in lesions.[45]

Atheroprotective Effects of PON1 in Animal Models

High–fat, high-cholesterol (atherogenic) diet leads to fast development of atherosclerosis in C57BL/6J mouse strain with concomitant decrease in liver PON1 expression. At the same time PON1 expression and its protective effects did not decrease in atherosclerosis-resistant strain C3H/HeJ.[46]

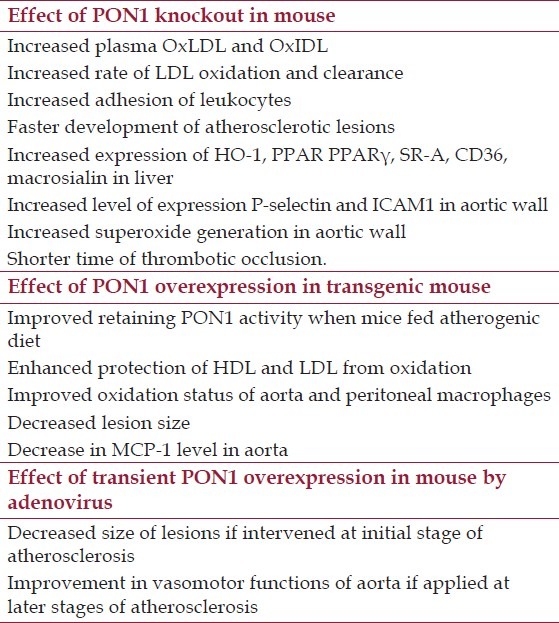

The first PON1 knockout mouse data became available in 1998. Macrophages from this mouse did not protect LDL from oxidation by other cells in vitro, and PON1 knockout mice developed atherosclerosis faster than control mice on high fat, high cholesterol diet.[13] To study the effect of PON1 knockout further, this mouse was crossed with ApoE knockout mice to generate PON1-/-, ApoE-/- mouse. The double knockout mice fed with atherogenic diet developed atherosclerosis faster than control. Plasma lipid profile of these double knockout mice was similar to ApoE-/- control animals with slightly decreased level of intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL) and LDL, and increased level of lysophosphatidylcholine and oxidized phospholipids in IDL and LDL. The rates of LDL oxidation and clearance were higher in PON1-/-, ApoE-/- mice than in control mice as was determined by injection of human LDL. Expression of genes responding to increase of OxLDL, such as heme oxygenase-1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, scavenger receptor type A, CD36, and macrosialin, was upregulated in liver of PON1-/-, ApoE-/- mice compared with ApoE-/- mice.[47]

Involvement of PON in inflammation and oxidative stress were detected in vascular wall of PON-/- animals. Adhesion of leukocytes was increased in the knockout mouse as measured by intravital microscopy. Expression of mRNA of essential cell adhesion molecules P-selectin and ICAM1 was upregulated in aortic wall. An increased oxidative status was detected using superoxide-sensitive reagent lucigenin. PON-/- mice have a significantly shorter time of occlusion in carotid thrombosis assay.[48] If a deficiency of PON1 leads to inflammation and oxidative stress, then increases in PON1 function could be beneficial. A transgenic mouse mPON1 was developed in 2001, with 5-fold higher level of mouse PON1 protein and corresponding increase in arylesterase activity. PON1 was associated with HDL, and protected HDL from oxidation by copper ions as it was assessed by lipid hydroperoxide formation assay, and by retaining oxidation-sensitive activity of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT).[49] A decrease in atherosclerotic lesion size and improved oxidation status of aorta and peritoneal macrophages in PON1 overexpressing transgenic mouse on ApoE-/- background have been compared with ApoE-/- control have been reported.[14] In another transgenic mouse model, PON1-Tg, which overexpresses human PON1 gene of 55L/192Q genotype, plasma level of arylesterase activity was twice higher in PON1-Tg mouse compared with control mouse when animals were fed normal chow. The excess of PON1 level resulted in better retaining of its activity after feeding animals with atherogenic diet. PON1 activity decreased to about three-fourth (3/4) of original level after 15 weeks of atherogenic diet feeding to PON1-Tg mice, and to less than one-half (1/2) of original level in control animals. Thus, arylesterase activity mediated by PON1 was almost 4-fold higher in PON1-Tg mice compared with control mice after feeding atherogenic diet. Overexpression of PON1 definitely protected mouse from development of atherosclerotic lesions. Aortic lesion areas in PON1-Tg animals were about half of the size of areas of the control mice after feeding atherogenic diet. ApoE-/-, PON1-Tg genotype mice fed normal chow similarly developed lesions slower, compared with ApoE-/- controls; however, the difference in lesion area was just 22%. Plasma arylesterase activity of ApoE-/-, PON1-Tg mice was 2.5-fold higher than that of ApoE-/- animals, however, there is no difference between their lipid profile. A decreased inflammatory status of aortas in ApoE-/-, PON1-Tg mice compared with ApoE-/- mice was detected by examination of the expression level of MCP-1 cytokine gene. HDL isolated from PON1-Tg mouse plasma or ApoE-/-, PON1-Tg mouse plasma provided better protection against LDL oxidation, than HDL isolated from control animals.[50]

Beside PON1 studies on transgenic mouse, a transient overexpression of PON1 gene in mouse was utilized to investigate effect of PON1. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of human PON1 gene (55M, 192Q genotype) in double knockout leptin-/- (ob/ob), LDLR-/- mouse resulted in more than 4-fold increase of PON1 activity on day 7 with gradual decrease to the control level by day 21. Mice were injected with adenovirus at the age of 18 weeks when the progression of atherosclerosis occurs in a fast rate. Six weeks later, cross-sections of the aortic root were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Plaque size, volume of macrophages, concentration of OxLDL was significantly lower in PON1 expressing animals. The titer of anti-OxLDL antibodies was lower in plasma of PON1 overexpressing mice as well.[51]

While an early PON1 intervention proved to have significant athero-protective effect, another study was performed to assess whether transient PON1 overexpression can improve vascular function in advanced atherosclerosis. Similar to the previous study, 55M/192Q variant of human PON1 gene was delivered in 18 month old ApoE-/- mouse fed normal chow using adenovirus vector. Serum PON1 activity was increased 10-fold by day 7 and 2.5-fold on the day 21 in PON1 overexpressing animals compared with controls. After 3 weeks, lesions were measured and no changes in their size were found. However, vasomotor function was improved by transient overexpression of PON1. Thus, phenylephrine-constricted segments of the aortas relaxed significantly better in response to endothelium dependent agonists ACh, adenosine-5’-triphosphate (ATP), and uridine-5’-triphosphate (UTP) observations on PON1 role in animal models is summarized in Table 2.[52]

Table 2.

Summary of observations on alterations of PON1 expression in mice

PON1 Serum Activity, Polymorphism and CAD in Human

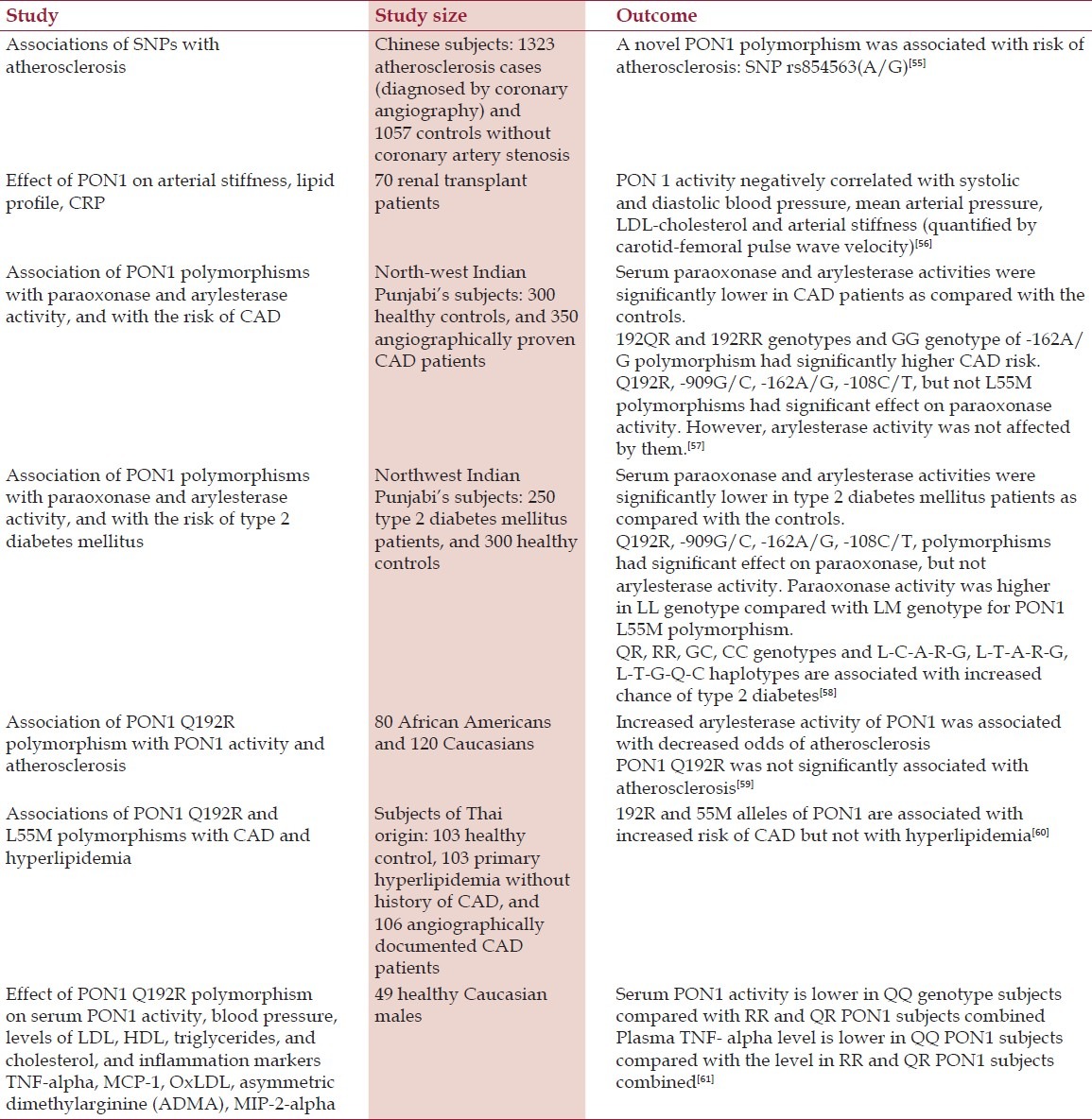

Meta-analysis of 47 studies with 9853 CAD and 11,408 control subjects published in 2012 confirmed association of lower plasma PON1 activity with increased CAD risk (19% lower PON1 activity, P < 0.00001).[53] Another meta-analysis published in 2012 included 43 studies with total 20,629 subjects showed similar association of PON1 activity and CAD with standardized mean difference (SMD) of -0.78 (P < 0.001) for CAD subjects compared with controls. Slightly weaker association was between arylesterase activity of PON1 and CAD with SMD of -0.50 (P < 0.001).[54] Both meta-analyses observed increased risk of CAD in subjects with lower PON1 regardless of age and ethnicity; Tables 3 and 4 summarizes the role of PON1 in human studies.

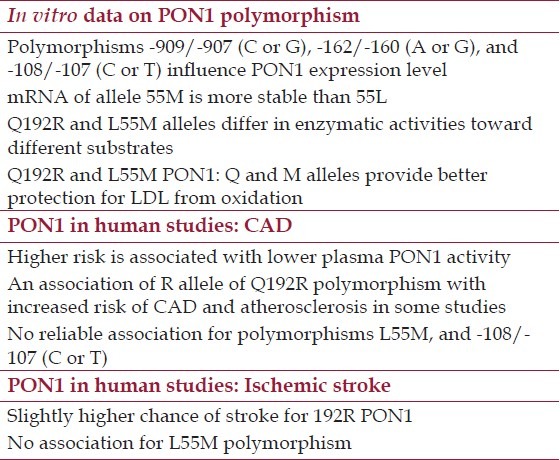

Table 3.

Summary of allele differences of PON1 in vitro, and conclusions from PON1 human studies

Table 4.

Recent human studies on the role of PON1 in CVD

Some alleles of polymorphous genes can be causative factors in development of diseases and reliable predictors. Several polymorphisms were detected in human PON1 gene. There are at least five known polymorphisms in promoter region of PON1: -909/-907 (C or G), -832/-824 (A or G), -162/-160 (A or G), -126 (C or G), and -108/-107 (C or T). Also, there are two polymorphisms in the PON1 coding region, Q192R (aka rs662 or 575A > G) and L55M (aka rs854560 or 163T > A), and several polymorphisms in 3’ untranslated region of the gene.[62] PON1 protein level in human serum varies more than 13-fold, and variations in the sequence of promoter region of PON1 gene might cause difference in its expression. Two-fold differences in expression level between alleles were observed in cell culture reporter gene assay for three polymorphisms: -909/-907 (C or G), -162/-160 (A or G), and -108/-107 (C or T). Polymorphisms -162/-160 (A or G) is a putative binding site for transcription factor NF-I, and -108/-107 (C or T) is a putative binding site for Sp1. No effect on expression level in the reporter gene assay was observed for -832/-824 (A or G), -162/-160 (A or G) polymorphisms.[18]

Gene expression and enzyme activity studies on PON1 polymorphisms in protein coding region Q192R and L55M resulted in several observations. First, messenger RNA of allele 55M appeared to be more stable than 55L as determined by PCR amplification and restriction analysis of cDNA synthesized from heterozygous liver samples. L55M heterozygous liver had roughly twice more mRNA of 55M allele compared with 55L. That might results in difference in protein expression levels between alleles and ultimately in PON1 activity and protection, although it was not assessed in the study.[63] Q192R and L55M alleles differ in their enzymatic activities. In a study of serum of 279 healthy human subjects hydrolytic activity of PON1 toward paraoxon was depending on both polymorphisms. PON1 protein level was relatively similar for all tested polymorphism variants. Activity of 55M homozygotes were always lower than 55L/M heterozygotes or 55L homozygotes.[64] Later studies revealed that Q192R polymorphism affect PON1 activity toward several substrates. QQ, QR, and RR phenotypes can be reliably determined by assaying PON1 catalytic activities toward two substrates: diazoxon and paraoxon. PON1 of QQ genotype exhibits relatively high activity toward diazoxon and relatively low activity toward paraoxon. RR genotype, opposite to QQ, exhibits low activity toward diazoxon and high activity toward paraoxon. QR phenotype exhibits intermediate activity toward both substrates.[65] 192R PON1 hydrolyzes homocysteine thiolactone faster than 192Q PON1.[66]

Q192R and L55M PON1 enzymes differ in their protection to LDL from oxidation in vitro using LDL oxidation assay with copper in the presence of HDL. PON1 of QQ/MM genotype provides the best antioxidant protection. Protection by PON1 decreases in the order of genotypes QQ > QR > RR with almost no antioxidant activity in RR genotype, and about a half of QQ activity in QR phenotype. The antioxidant activity of PON1 decreased in the series MM > LM > LL, with the activity of LL genotype about a half of activity of MM genotype.[67]

Multiple clinical studies were performed to expose whether PON1 polymorphism may contribute to CAD and other diseases. Currently, analyses of association of PON1 polymorphism with atherosclerosis-related diseases determined just one reliable association, an association of Q192R polymorphism with ischemic stroke. Meta-analysis of 22 studies have been published earlier up to mid of 2009, totaling 7384 ischemic stroke subjects and 11,074 controls revealed odds ratio of 1.10 for G (192R) allele (95% CI: 1.04–1.17).[68] Another meta-analysis study that was published in 2010 and summarized results of 11 studies confirmed that 192R allele confers significant risk of ischemic stroke (odds ratio =1.25, 95% CI: 1.07,1.46, P = 0.006). Surprisingly, this risk is confined to Caucasian subjects, but there is no significant association of 192R allele of PON1 and ischemic stroke in East Asian population.[69]

Association of PON1 polymorphism Q192R with CAD was examined in extensive meta-analysis of studies published before 2011. Per-allele odds ratio for CAD for 192R was 1.11 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.17) based on all studies regardless of their size. However, analysis suggested that small studies were less reliable, perhaps because of small studies bias. No significant association of 192R allele with CAD was observed when 10 larger studies with more than 500 cases each were analyzed.[70] Similar conclusions regarding small study bias and the absence of reliable association of Q192R polymorphism with CAD were concluded in two other independent massive meta-analysis studies published in 2004;[71,72] also, no association was found between CAD and L55M or -108/-107 (C or T) polymorphisms of PON1 gene. Meta-analysis for L55M and -108/-107 (C or T) PON1 polymorphisms determined per-allele odds ratios for CAD as 0.94 (95% CI: 0.88,1.00) for 55M and 1.02 (95% CI: 0.911.15) for -108/-107 C, respectively. No significant association of L55M or -108/-107 (C or T) PON1 polymorphisms with CAD were observed in an earlier meta-analysis study.[72]

No association between L55M (rs854560) polymorphism and ischemic stroke was found in meta-analysis of 16 studies published before mid-2009 totaling 5518 ischemic stroke subjects and 8951 controls.[68] Similarly, a meta-analysis published in 2010 for 10 studies did not find significant association 55L allele with stroke regardless on the stroke type, age of patients, and ethnicity.[69]

Resent human studies generally support the conclusions of meta-analyses [Table 4]. A novel PON1 polymorphism associated with atherosclerosis was recently revealed, SNP rs854563(A/G).[55]

In conclusion, PON1 antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect is extensively examined in vitro, in cell culture and animal models. Human studies confirm protective role of PON1 in CAD and another atherosclerosis-related disease, ischemic stroke. Although the current knowledge of PON1 provides valuable insights on the function and role of PON1, yet mechanism of PON1 action is still not well investigated. Transient overexpression of PON1 in mouse demonstrated beneficial effects of PON1 beyond its antiatherogenic properties. Further research of PON1 could potentially lead to new clinical strategies in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work has been supported by a startup fund from the University of Massachusetts Lowell for Dr. Mahdi Garelnabi.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Primo-Parmo SL, Sorenson RC, Teiber JF, La Du BN. The human serum paraoxonase/arylesterase gene (PON1) is one member of a multigene family. Genomics. 1996;33:498–507. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harel M, Aharoni A, Gaidukov L, Brumshtein B, Khersonsky O, Meged R, et al. Structure and evolution of the serum paraoxonase family of detoxifying and anti-atherosclerotic enzymes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:412–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Draganov DI, Teiber JF, Speelman A, Osawa Y, Sunahara R, La Du BN. Human paraoxonases (PON1, PON2, and PON3) are lactonases with overlapping and distinct substrate specificities. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1239–47. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400511-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS. Structure-reactivity studies of serum paraoxonase PON1 suggest that its native activity is lactonase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6371–82. doi: 10.1021/bi047440d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerkeni M, Addad F, Chauffert M, Chuniaud L, Miled A, Trivin F, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia, paraoxonase activity and risk of coronary artery disease. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:821–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg D, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Khoo JC, Witztum JL. Beyond cholesterol.Modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:915–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904063201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy S, Barnett J, Fong LG. High-density lipoprotein inhibits the oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1044:275–83. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90314-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackness MI, Arrol S, Durrington PN. Paraoxonase prevents accumulation of lipoperoxides in low-density lipoprotein. FEBS Lett. 1991;286:152–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Bisgaier CL, Newton RS, Primo-Parmo SL, La Du BN. Paraoxonase inhibits high-density lipoprotein oxidation and preserves its functions.A possible peroxidative role for paraoxonase. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1581–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackness MI, Arrol S, Abbott C, Durrington PN. Protection of low-density lipoprotein against oxidative modification by high-density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase. Atherosclerosis. 1993;104:129–35. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90183-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson DD, Berliner JA, Hama SY, La Du BN, Faull KF, Fogelman AM, et al. Protective effect of high density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase.Inhibition of the biological activity of minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2882–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI118359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teiber JF, Draganov DI, La Du BN. Purified human serum PON1 does not protect LDL against oxidation in the in vitro assays initiated with copper or AAPH. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:2260–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400213-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih DM, Gu L, Xia YR, Navab M, Li WF, Hama S, et al. Mice lacking serum paraoxonase are susceptible to organophosphate toxicity and atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:284–7. doi: 10.1038/28406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rozenberg O, Shih DM, Aviram M. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) attenuates macrophage oxidative status: Studies in PON1 transfected cells and in PON1 transgenic mice. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassett C, Richter RJ, Humbert R, Chapline C, Crabb JW, Omiecinski CJ, et al. Characterization of cDNA clones encoding rabbit and human serum paraoxonase: The mature protein retains its signal sequence. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10141–9. doi: 10.1021/bi00106a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackness B, Beltran-Debon R, Aragones G, Joven J, Camps J, Mackness M. Human tissue distribution of paraoxonases 1 and 2 mRNA. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:480–2. doi: 10.1002/iub.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shamir R, Hartman C, Karry R, Pavlotzky E, Eliakim R, Lachter J, et al. Paraoxonases (PONs) 1, 2, and 3 are expressed in human and mouse gastrointestinal tract and in Caco-2 cell line: Selective secretion of PON1 and PON2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:336–44. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brophy HV, Hastings MD, Clendenning JB, Richter RJ, Jarvik GP, Furlong CE. Polymorphisms in the human paraoxonase (PON1) promoter. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:77–84. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda Y, Suehiro T, Arii K, Kumon Y, Hashimoto K. High glucose induces transactivation of the human paraoxonase 1 gene in hepatocytes. Metabolism. 2008;57:1725–32. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osaki F, Ikeda Y, Suehiro T, Ota K, Tsuzura S, Arii K, et al. Roles of Sp1 and protein kinase C in regulation of human serum paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene transcription in HepG2 cells. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176:279–87. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ota K, Suehiro T, Arii K, Ikeda Y, Kumon Y, Osaki F, et al. Effect of pitavastatin on transactivation of human serum paraoxonase 1 gene. Metabolism. 2005;54:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arii K, Suehiro T, Ota K, Ikeda Y, Kumon Y, Osaki F, et al. Pitavastatin induces PON1 expression through p44 / 42 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade in Huh7 cells. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deakin S, Leviev I, Guernier S, James RW. Simvastatin modulates expression of the PON1 gene and increases serum paraoxonase: A role for sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2083–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000096207.01487.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouédard C, Barouki R, Morel Y. Dietary polyphenols increase paraoxonase 1 gene expression by an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5209–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5209-5222.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaichander P, Selvarajan K, Garelnabi M, Parthasarathy S. Induction of paraoxonase 1 and apolipoprotein A-I gene expression by aspirin. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2142–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800082-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gouédard C, Barouki R, Morel Y. Induction of the paraoxonase-1 gene expression by resveratrol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2378–83. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000146530.24736.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng CC, Hsueh CM, Liang KW, Ting CT, Wen CL, Hsu SL. Role of JNK and c-Jun signaling pathway in regulation of human serum paraoxonase 1 gene transcription by berberine in human HepG2 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;650:519–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutierrez A, Ratliff EP, Andres AM, Huang X, McKeehan WL, Davis RA. Bile acids decrease hepatic paraoxonase 1 expression and plasma high-density lipoprotein levels via FXR-mediated signaling of FGFR4. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:301–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000195793.73118.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shih DM, Kast-Woelbern HR, Wong J, Xia YR, Edwards PA, Lusis AJ. A role for FXR and human FGF-19 in the repression of paraoxonase-1 gene expression by bile acids. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:384–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500378-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalvo MC, Gil F, Hernandez AF, Rodrigo L, Villanueva E, Pla A. Human liver paraoxonase (PON1): Subcellular distribution and characterization. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 1998;12:61–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0461(1998)12:1<61::aid-jbt8>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deakin S, Leviev I, Gomaraschi M, Calabresi L, Franceschini G, James RW. Enzymatically active paraoxonase-1 is located at the external membrane of producing cells and released by a high affinity, saturable, desorption mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4301–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deakin S, Moren X, James RW. Very low density lipoproteins provide a vector for secretion of paraoxonase-1 from cells. Atherosclerosis. 2005;179:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorenson RC, Bisgaier CL, Aviram M, Hsu C, Billecke S, La Du BN. Human serum Paraoxonase/Arylesterase's retained hydrophobic N-terminal leader sequence associates with HDLs by binding phospholipids: Apolipoprotein A-I stabilizes activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2214–25. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schultz JR, Verstuyft JG, Gong EL, Nichols AV, Rubin EM. Protein composition determines the anti-atherogenic properties of HDL in transgenic mice. Nature. 1993;365:762–4. doi: 10.1038/365762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaidukov L, Tawfik DS. High affinity, stability, and lactonase activity of serum paraoxonase PON1 anchored on HDL with ApoA-I. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11843–54. doi: 10.1021/bi050862i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaidukov L, Viji RI, Yacobson S, Rosenblat M, Aviram M, Tawfik DS. ApoE induces serum paraoxonase PON1 activity and stability similar to ApoA-I. Biochemistry. 2010;49:532–8. doi: 10.1021/bi9013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noto H, Hashimoto Y, Satoh H, Hara M, Iso-o N, Togo M, et al. Exclusive association of paraoxonase 1 with high-density lipoprotein particles in apolipoprotein A-I deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:395–401. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribas V, Sánchez-Quesada JL, Antón R, Camacho M, Julve J, Escolà-Gil JC, et al. Human apolipoprotein A-II enrichment displaces paraoxonase from HDL and impairs its antioxidant properties: A new mechanism linking HDL protein composition and antiatherogenic potential. Circ Res. 2004;95:789–97. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146031.94850.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escolà-Gil JC, Marzal-Casacuberta A, Julve-Gil J, Ishida BY, Ordóñez-Llanos J, Chan L, et al. Human apolipoprotein A-II is a pro-atherogenic molecule when it is expressed in transgenic mice at a level similar to that in humans: Evidence of a potentially relevant species-specific interaction with diet. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deakin SP, Bioletto S, Bochaton-Piallat ML, James RW. HDL-associated paraoxonase-1 can redistribute to cell membranes and influence sensitivity to oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuhrman B, Volkova N, Aviram M. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) is present in postprandial chylomicrons. Atherosclerosis. 2005;180:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodrigo L, Hernández AF, López-Caballero JJ, Gil F, Pla A. Immunohistochemical evidence for the expression and induction of paraoxonase in rat liver, kidney, lung and brain tissue. Implications for its physiological role. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;137:123–37. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marsillach J, Mackness B, Mackness M, Riu F, Beltrán R, Joven J, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of paraoxonases-1, 2, and 3 expression in normal mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:146–57. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackness B, Hunt R, Durrington PN, Mackness MI. Increased immunolocalization of paraoxonase, clusterin, and apolipoprotein A-I in the human artery wall with the progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1233–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.7.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marsillach J, Camps J, Beltran-Debón J, Rull A, Aragones G, Maestre-Martínez C, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of paraoxonases-1 and 3 in human atheromatous plaques. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:308–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shih DM, Gu L, Hama S, Xia YR, Navab M, Fogelman AM, et al. Genetic-dietary regulation of serum paraoxonase expression and its role in atherogenesis in a mouse model. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1630–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI118589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shih DM, Xia YR, Wang XP, Miller E, Castellani LW, Subbanagounder G, et al. Combined serum paraoxonase knockout/apolipoprotein E knockout mice exhibit increased lipoprotein oxidation and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17527–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910376199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ng DS, Chu T, Esposito B, Hui P, Connelly PW, Gross PL. Paraoxonase-1 deficiency in mice predisposes to vascular inflammation, oxidative stress, and thrombogenicity in the absence of hyperlipidemia. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oda MN, Bielicki JK, Ho TT, Berger T, Rubin EM, Forte TM. Paraoxonase 1 overexpression in mice and its effect on high-density lipoproteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:921–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tward A, Xia YR, Wang XP, Shi YS, Park C, Castellani LW, et al. Decreased atherosclerotic lesion formation in human serum paraoxonase transgenic mice. Circulation. 2002;106:484–90. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023623.87083.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackness B, Quarck R, Verreth W, Mackness M, Holvoet P. Human paraoxonase-1 overexpression inhibits atherosclerosis in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1545–50. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000222924.62641.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guns PJ, Van Assche T, Verreth W, Fransen P, Mackness B, Mackness M, et al. Paraoxonase 1 gene transfer lowers vascular oxidative stress and improves vasomotor function in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice with pre-existing atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:508–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang M, Lang X, Cui S, Zou L, Cao J, Wang S, et al. Quantitative Assessment of the Influence of Paraoxonase 1 Activity and Coronary Heart Disease Risk. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31:975–82. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao Y, Ma Y, Fang Y, Liu L, Wu S, Fu D, et al. Association between PON1 activity and coronary heart disease risk: A meta-analysis based on 43 studies. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;105:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Fu W, Xie F, Wang Y, Chu X, Wang H, et al. Common polymorphisms in ITGA2, PON1 and THBS2 are associated with coronary atherosclerosis in a candidate gene association study of the Chinese Han population. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:490–4. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gungor O, Kircelli F, Demirci MS, Tuncel P, Sisman AR, Tatar E, et al. Serum paraoxonase 1 activity predicts arterial stiffness in renal transplant recipients. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18:901–5. doi: 10.5551/jat.9175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta N, Singh S, Maturu VN, Sharma YP, Gill KD. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) polymorphisms, haplotypes and activity in predicting cad risk in North-West Indian Punjabis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta N, Binukumar BK, Singh S, Sunkaria A, Kandimalla R, Bhansali A, et al. Serum paraoxonase-1 (PON1) activities (PONase/AREase) and polymorphisms in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a North-West Indian population. Gene. 2011;487:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coombes RH, CrowJA , Dail MB, Chambers HW, Wills RW, Bertolet BD, et al. Relationship of human paraoxonase-1 serum activity and genotype with atherosclerosis in individuals from the Deep South. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21:867–75. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834cebc6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Likidlilid A, Akrawinthawong K, Poldee S, Sriratanasathavorn C. Paraoxonase 1 polymorphisms as the risk factor of coronary heart disease in a Thai population. Acta Cardiol. 2010;65:681–91. doi: 10.1080/ac.65.6.2059866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lüersen K, Schmelzer C, Boesch-Saadatmandi C, Kohl C, Rimbach G, Döring F. Paraoxonase 1 polymorphism Q192R affects the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha in healthy males. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:141. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brophy VH, Jampsa RL, Clendenning JB, McKinstry LA, Jarvik GP, Furlong CE. Effects of 5’ regulatory-region polymorphisms on paraoxonase-gene (PON1) expression. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1428–36. doi: 10.1086/320600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leviev I, Negro F, James RW. Two alleles of the human paraoxonase gene produce different amounts of mRNA.An explanation for differences in serum concentrations of paraoxonase associated with the (Leu-Met54) polymorphism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2935–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mackness B, Mackness MI, Arrol S, Turkie W, Durrington PN. Effect of the molecular polymorphisms of human paraoxonase (PON1) on the rate of hydrolysis of paraoxon. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:265–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richter RJ, Jampsa RL, Jarvik GP, Costa LG, Furlong CE. Determination of paraoxonase 1 status and genotypes at specific polymorphic sites. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2004 doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx0412s19. Chapter 4:Unit 4.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bayrak A, Bayrak T, Demirpençe E, Kılınç K. Differential hydrolysis of homocysteine thiolactone by purified human serum (192)Q and (192)R PON1 isoenzymes. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mackness B, Mackness MI, Arrol S, Turkie W, Durrington PN. Effect of the human serum paraoxonase 55 and 192 genetic polymorphisms on the protection by high density lipoprotein against low density lipoprotein oxidative modification. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dahabreh IJ, Kitsios GD, Kent DM, Trikalinos TA. Paraoxonase 1 polymorphisms and ischemic stroke risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Med. 2010;12:606–15. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ee81c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Banerjee I. Relationship between Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene polymorphisms and susceptibility of stroke: A meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:449–58. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang M, Lang X, Zou L, Huang S, Xu Z. Four genetic polymorphisms of paraoxonase gene and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis based on 88 case-control studies. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:377–85. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lawlor DA, Day IN, Gaunt TR, Hinks LJ, Briggs PJ, Kiessling M, et al. The association of the PON1 Q192R polymorphism with coronary heart disease: Findings from the British Women's Heart and Health cohort study and a meta-analysis. BMC Genet. 2004;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wheeler JG, Keavney BD, Watkins H, Collins R, Danesh J. Four paraoxonase gene polymorphisms in 11212 cases of coronary heart disease and 12786 controls: Meta-analysis of 43 studies. Lancet. 2004;363:689–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]