Abstract

We have reported previously that daily intravenous infusions of a soluble nanobiotechnological complex, polyhemoglobin-tyrosinase [polyHb-Tyr], can suppress the growth of murine B16F10 melanoma in a mouse model. In order to avoid the need for daily intravenous injections, we have now extended this further as follows. We have prepared two types of biodegradable nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. One type is to increase the circulation time and decrease the frequency of injection and is based on polyethyleneglycol-polylactic acid (PEG-PLA) nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. The other type is to allow for intratumoural or local injection and is based on polylactic acid (PLA) nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. Cell culture studies show that it can inhibit the proliferation of murine B16F10 melanoma cells in the “proliferation model”. It can also inhibit the attachment of murine B16F10 melanoma cells in the “attachment model.” This could be due to the action of tyrosinase on the depletion of tyrosine or the toxic effect of tyrosine metabolites. The other component, polyhemoglobin (polyHb), plays a smaller role in nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr], and this is most likely by its depletion of nitric oxide needed for melanoma cell growth.

1. Introduction

Deregulated proliferation and differentiation of melanocytes lead to the formation of melanoma [1]. Although not as common as the other skin basal cell skin cancer or skin squamous cell cancer, melanoma is far more dangerous. Surgical removal is effective in the early stage. However, once it has metastasized beyond the local lymph nodes, it is eventually fatal [2–4]. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other approaches in combination are being investigated [5–10].

Melanoma cells show specific amino acid-dependence for Tyrosine (Tyr) and phenylalanine (Phe) [11–14] and also arginine [15, 16]. Tyr/Phe deprivation induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in murine melanoma [17] and induces apoptosis by inhibiting integrin/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) pathway and activating caspases [18–20]. Tyr/Phe deprivation induces apoptosis in murine and human melanoma cells but not in normal cells [21]. One method is to utilize the tyrosinase-dependent catalytic reaction to suppress Tyr level and also consume Phe [22, 23]. In addition, the generated products of tyrosine metabolism, such as dopa, 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI), 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) and others, are also toxic to melanoma cells [24]. Oxidation of these tyrosine metabolites can produce reactive oxygen species [24]. In the melanoma cells, the excessive reactive oxygen species will stimulate cell apoptosis by activating DNA damage-repair pathway and also opening mitochondrial pore [25]. Despite the potential of tyrosinase, injection of free enzymes has problems related to immunology, stability, and duration of action.

Artificial cells bioencapsulated enzymes were first prepared for different medical applications [26]. This approach has shown potentials in catalase for the depletion of hydrogen peroxide in acatalasemia [27], asparaginase for the depletion of asparagine for 6C3HED lymphosarcoma [28], phenylalanine ammonia-lyase for the depletion of phenylalanine in phenylketonuria [29], and xanthine oxidase to remove hypoxanthine in Lesch-Nyhan Disease [30]. Detailed in vitro studies show that the enzyme in artificial cells no longer has immunological problems [31]. Two further developments have led to the possible clinical applications of these animal studies. One is the development of nanobiotechnological approach for artificial cells [32]. Another development is the first artificial cells with biodegradable polymeric membrane [33]. These have now led to extensive developments in this area [34–36].

One area is the clinical applications of oxygen therapeutics using the basic nanobiotechnological procedure of crosslinking hemoglobin [32] to form soluble polyHb [37, 38]. PolyHb has been tested in phase III clinical trials as blood substitutes [39, 40] and has now been approved for routine clinical patient uses in Russia and South Africa. These oxygen carriers have also been tested in animal studies and found to increase tissue oxygenation and enhance radiation and chemotherapy in solid tumors [41, 42]. We have methods for the crosslinking of enzymes to hemoglobin to form polyHb-enzyme systems [37, 38, 43]. We therefore studied the crosslinking of tyrosinase to hemoglobin to form polyHb-tyrosinase [44, 45]. The increased tissue oxygenation could then be an additive effect on Tyr depletion for melanoma. Our studies show that this approach can significantly suppress the growth of murine B16F10 melanoma mice [44]. However, polyHb-tyrosinase requires daily intravenous infusions. Furthermore, polyHb-tyrosinase is a solution that does not stay at the site of intratumoural and local injection. This solution also cannot be located at the drainage lymphatic nodes or organs. We are in the process of improving this approach by combining the nanobiotechnological approach of polyHb-tyrosinase with biodegradable nanodimension artificial cells. We have developed the original biodegradable polymeric artificial cells [33] into a nanodimension system that can be given intravenously [46]. PolyHb in PEG-PLA membrane nanodimension artificial cells has a much longer circulation time than polyHb [47]. Infusion of 1/3 the total blood volume into rats does not cause long-term adverse effects on the histology and function of liver, spleen, and kidney [48, 49]. Other centers are now using this approach [50–53].

In order to avoid the need for daily intravenous injections, in the present study we have prepared two types of biodegradable nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. One type is to increase the circulation time and decrease the frequency of injection and is based on PEG-PLA nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. The other type is to allow for intratumoural or local injection and is based on PLA nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. The cell culture study shows that it can inhibit the proliferation of murine B16F10 melanoma cells in the “proliferation model.” It can also inhibit the attachment of murine B16F10 melanoma cells in the “attachment model.” The component analysis shows that the enzymatic action of tyrosinase on tyrosine plays the major role in nanocapsule-[polyHb-Tyr]. This could be due to the depletion of tyrosine or the toxic effects of the metabolites of tyrosine. The other component, polyHb, plays a smaller role in nanocapsule-[polyHb-Tyr], and this is most likely due to its depletion of nitric oxide needed for melanoma cell growth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PolyHb and PolyHb-Tyrosinase Preparations

This is as described in detail elsewhere [36, 44, 45]. Briefly, stroma-free hemoglobin (SFHb) with a concentration of 7 g/dL Hb with or without tyrosinase was dissolved in a 0.1 mol/L sodium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4). Lysine was added at a molar ratio of 7 : 1 lysine/hemoglobin. Glutaraldehyde as a crosslinker was added at a molar ratio of 16 : 1 glutaraldehyde/hemoglobin. The process of crosslink continued for 24 hours. After that, lysine was added again to stop the crosslink reaction at a molar ratio of 200 : 1 lysine/hemoglobin. The sample was dialyzed overnight with a dialysis membrane (molecular weight cut-off = 12–14 kDa) and then passed through sterile 0.45 μm syringe filters to remove impurities. All operations were conducted at 4°C and under nitrogen in order to prevent the formation of methemoglobin and the degradation of enzyme.

2.2. Tyrosinase Nanocapsules Preparation

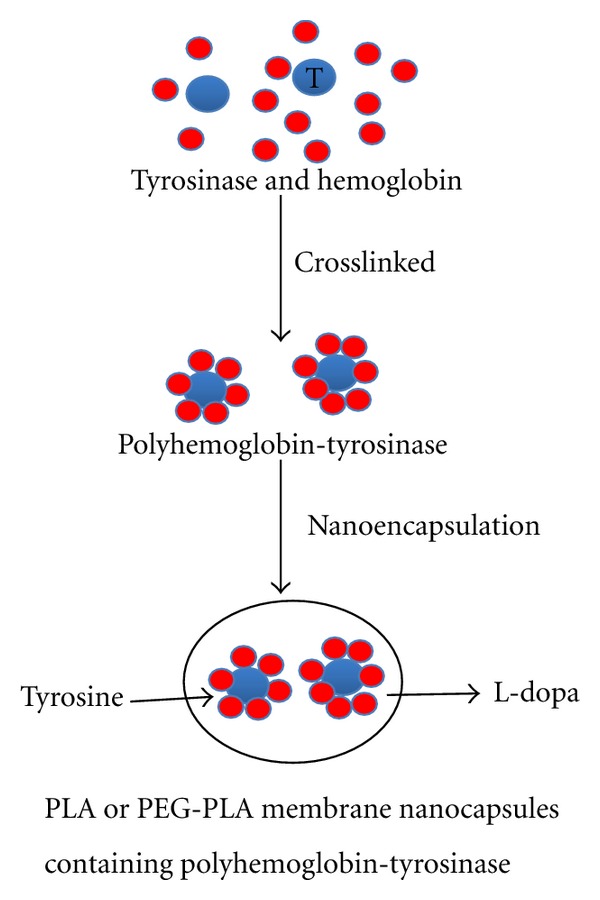

Nanocapsules were prepared as described [54] (Figure 1). Briefly, 50 mg PLA and 25 mg hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine were firstly dissolved in 4 mL acetone and 2 mL ethanol by sonication for 30 min. The formed organic phase was dropwise added into 5 mL 7 g/dL polyHb-Tyr solution with a syringe under moderate magnetic stirring. Then the suspension was stirred continually for 30 min. The organic solvent was removed using rotary evaporator under vacuum for about 1 hour. Then the resultant nanocapsules were separated by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 20 min to separate the supernatant and sediment. Then the suspension was concentrated with filtration.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the preparation of nanobiotechnological procedure for the PLA or PEG-PLA membrane nanocapsules containing polyhemoglobin-tyrosinase. Tyrosinase: larger blue circles. Hemoglobin: smaller red circles.

2.3. Molecular Weight Distribution

Sephacryl-300 HR column (V total = 560 mL) was used for molecular weight distribution analysis of polyHb-Tyr. The elution buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl and 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.4) at a flow rate of 36 mL/hour) was monitored by a 280 nm UV detector. Three molecular weight fractions were collected (1) >450 kDa, (2) 100–450 kDa, and (3) >100 kDa.

2.4. Tyrosinase Activity Assay

In our assay, tyrosinase catalyzes the substrate tyrosine into L-dopa under O2, and the formed L-dopa is then converted into L-dopa-quinone and H2O. Tyrosinase activity was tracked by monitoring the production rate of the enzymatic product L-dopaquinone at 300 nm, as described previously [54]. Briefly, the reaction solution was prepared with 0.34 mM L-tyrosine and 12.8 mM potassium phosphate buffer. This solution was adjusted to pH 6.5 and oxygenated by bubbling oxygen through for 10 minutes before usage. 10 to 100 μL of samples were mixed with the reaction solution 2.9 mL in a cuvette. Absorbance at 300 nm was monitored. The generated absorbance values were converted into enzyme activity unit by comparing with standard curves.

2.5. Tyrosinase Entrapment Efficiency

Drug entrapment efficiency of the nanocapsule was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

2.6. Physicochemical Characterization of Nanocapsules

The size and morphological examination of nanocapsules were performed by Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Specifically, about 10 uL nanocapsule samples were placed on 200 mesh carbon-coated copper grids and then examined with a JEOL JEM-2000FX microscope (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and photographed with a Gatan Wide Angle Multiscan CCD Camera.

2.7. Tumour Cells and Culture Conditions

B16F10 murine melanoma cells (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, #CRL-6475) were cultured in standard Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C and 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere. Cells were passaged every 2-3 days. When the cells reached 90–100% confluence, they were washed with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA for about 1 min to be detached from the dish. Then cell suspensions were collected in a sterile 15 mL tube and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min. Cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion and suspended in fresh medium to the desire density.

2.8. Cell Proliferation Assays

5 × 104 Melanoma cells in 2 mL complete DMEM were seeded in 6-well plates. When the tumor cells became 30–40% confluent, different nanocapsules or the same amount of saline were mixed with DMEM and added into each well. Cells were cultured for 0, 24, and 48 hours and collected by 0.25% trypsin/EDTA. The cell proliferative ability was then determined by trypan blue exclusion. The data from triplicate wells were averaged, and each experiment was repeated three times.

2.9. Cell Attachment Assays

For the experiment, melanoma cells suspension was mixed with different nanocapsules formats or the same amount of saline in the complete DMEM. Then the cells together with nanocapsules were mixed well and seeded in 6-well plates for 0, 24, and 48 hours observation. Use PBS to wash the unattached tumor cells, and collect the attached tumor cells by 0.25% trypsin/EDTA. The cell attachment ability was then determined by trypan blue exclusion. The data from triplicate wells were averaged, and each experiment was repeated three times.

2.10. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test within analysis of variance and was considered to be significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of PLA Nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr]

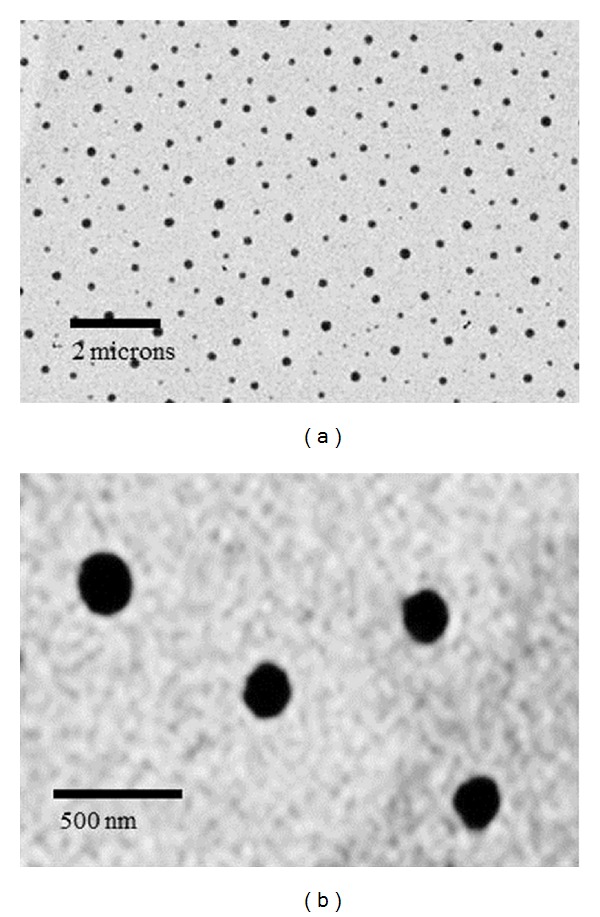

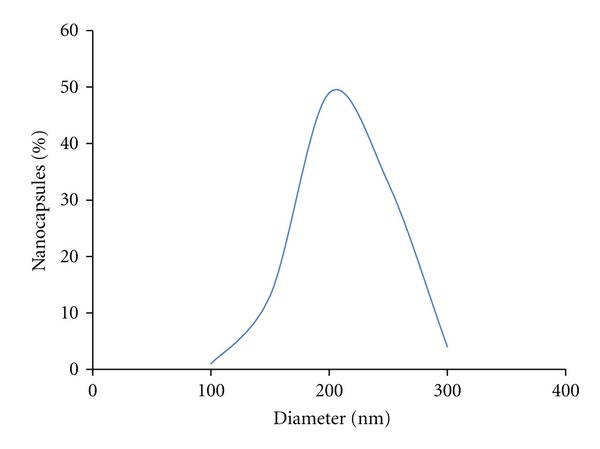

TEM image showed that the PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] was spherical with smooth surface and freely dispersed (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)). The size distribution based on the TEM images showed a range from 88 to 267 nm (187 ± 35 nm), and 64% of the nanocapsules are in the range of 120 to 200 nm (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Physicochemical characteristics of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr]. (a) TEM of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] at low magnification. (b) TEM of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] at high magnification.

Figure 3.

Size distribution of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr].

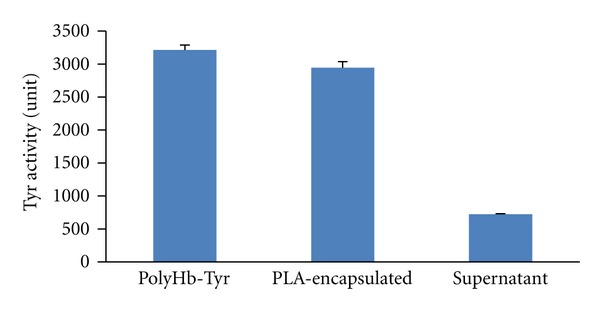

3.2. Nanoencapsulation Efficiency of PLA Nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr]

Sepacryl S-300 gel column chromatography was used to analyze the molecular weight distribution of polyHb-Tyr. The molecular weight distributions for polyHb-Tyr showed three types of molecular weight distributions: (1) low (<100 kDa), (2) intermediate (100–450 kDa), and (3) high molecular weight (>450 kDa). The low molecular weight fraction (<100 kDa) (11.5% of the sample) was discarded. The fraction of >100 kDa (88.5% of the samples) was used for nanoencapsulation. The encapsulation efficiency was 75.4% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Entrapment efficiency of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr].

3.3. Effects of PLA Nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] on the Proliferation of B16F10 Cells

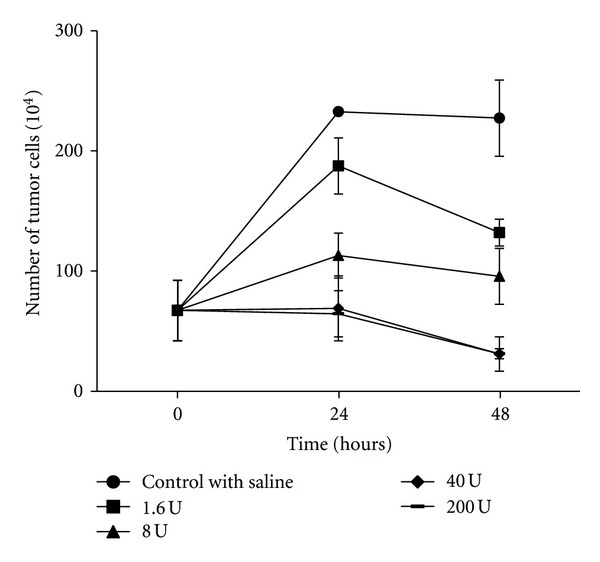

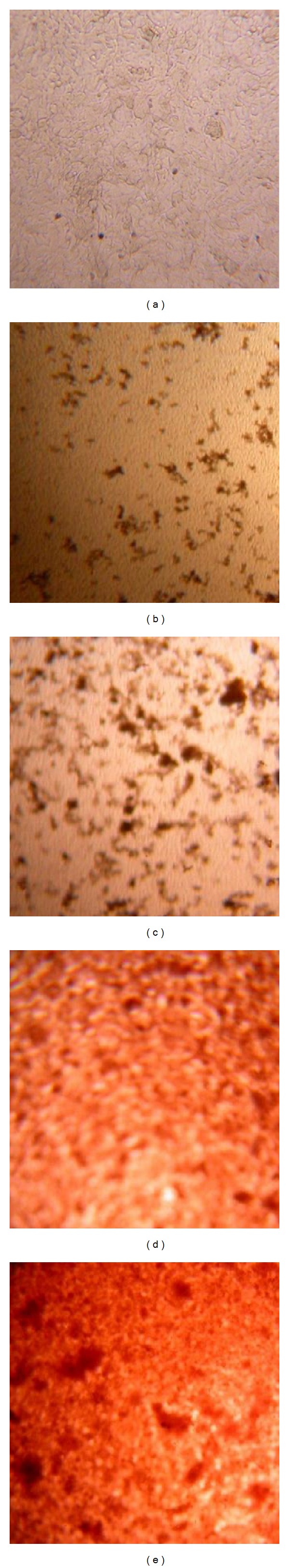

We treated B16F10 melanoma cells with PLA nanocapsules [polyHb-Tyr] containing a large range of enzyme activities, from 1.6 units to 200 units. The result showed that PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] inhibited tumor proliferation, and the effect was tyrosinase dose dependence. Compared with the control group, the higher the tyrosinase activity the greater was the inhibition of tumour proliferation as shown by the decrease in cell viability at 24 hours and 48 hours. At 48 hours, the tumour cells growth was most effectively inhibited in the groups of 40 units and 200 units of tyrosinase activity (Figure 5). The control group showed normal morphology with spindle-shaped and epithelial-like features (Figure 6(a)); after the treatment with PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr], dead cell clusters were observed with more dead cell clusters in the higher tyrosinase groups (Figures 6(b) to 6(e)).

Figure 5.

The effects of different amounts of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] on the proliferation of B16F10 melanoma cells.

Figure 6.

Effects of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] on the proliferation of B16F10 melanoma cells. The microscopy images of B16F10 melanoma cells treated with the nanocapsules containing enzyme activities increasing in enzyme activity from (a) to (e): 0, 1, 6, 8, 40, 200 units.

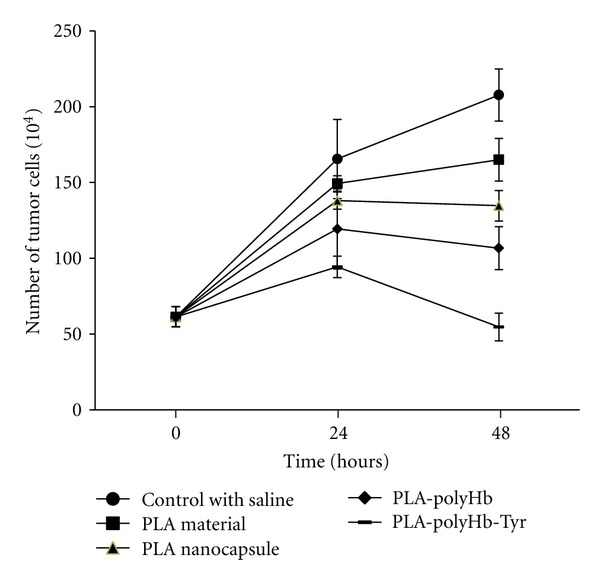

We also carried out a study to analyze the different PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] components on the inhibition of cells proliferation (Figure 7). The components tested included the PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] group, the PLA material, empty PLA nanocapsules, and PLA nanocapsule [polyHb] without tyrosinase. The result showed that PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] was responsible for the major role in the inhibition of cells proliferation. PLA nanocapsule [polyHb] can also suppress the tumor cells growth although not as much as that of the PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr]. In addition, the PLA material and empty PLA nanocapsule showed a very slight activity. Collectively, these results suggested that the PLA nanocapsule containing polyHb-Tyr had the ability to inhibit the tumor cells proliferation and the tyrosinase contributed to the major effect.

Figure 7.

PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] and the effects of its components on the proliferation of B16F10 melanoma cells.

3.4. Effects of PLA Nanocapsule PolyHb-Tyr on the Attachment of B16F10 Cells

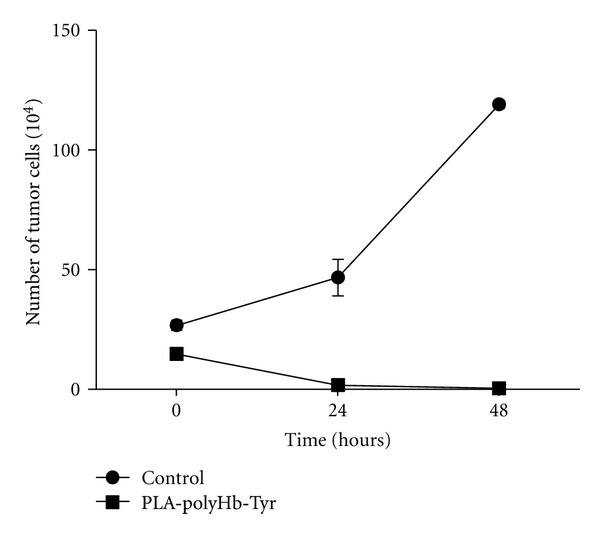

For the solid cancer melanoma, the metastatic dissemination from a primary lesion to a secondary site is believed to be the major reason leading to death [55, 56]. The tumor cells attached to the secondary site is one of the vital steps of this metastatic process [57]. Thus, we carried out the following experiment to identify the effect of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] on melanoma cell attachment. We mixed melanoma cells and PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] and cocultured the suspension solution in 6 well plates to observe the cell viability. It was found PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] effectively inhibited tumor cells attachment to plastic plates. In 24 hours, most of the tumor cells died and by 48 hours of culture there were no viable cells (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The effects of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] on the attachment ability of B16F10 melanoma cells.

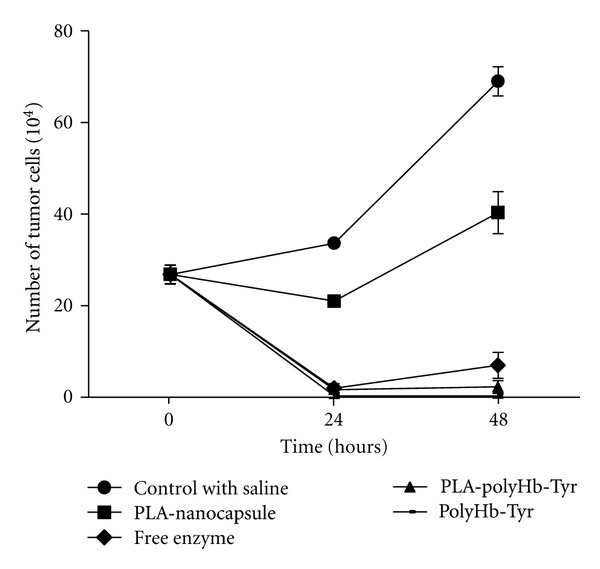

We also tested the different components of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr]. Saline was used as negative control and the free tyrosinase as positive control. Free tyrosinase reached its maximal effect at 24 hours. PolyHb-Tyr could inhibit tumor cells attachment in 24 hours culture and maintain this function to 48 hours. At 24 hour, PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] was as effective as free enzyme and polyHb-Tyr and this was maintained for 48 hours. Empty PLA nanocapsules had a slight effect at 24 hours, but this effect was minimal by 48 hours (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The effects of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-tyr] and the functions of its components on the attachment of B16F10 melanoma cells.

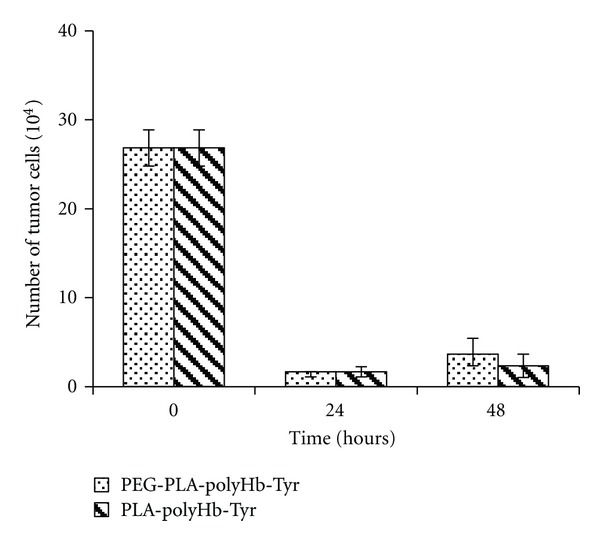

PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] is for the use in intratumoural and local injection. For intravenous injection, we have prepared PEG-PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr]. A comparison of PEG-PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] and PLA-nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] showed that there were no significant differences in their effects on B16F10 melanoma cells (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The functions of PEG-PLA and PLA nanocapsules on the attachment of B16F10 melanoma cells.

4. Discussion

Oxygen carriers increase tissue oxygenation in poorly perfused solid tumours and increase the sensitivity of the tumours to radiation and chemotherapy [41, 42]. By crosslinking tyrosinase to hemoglobin to form polyhemoglobin-tyrosinase, we can simultaneously act on tyrosine and increase oxygenation for melanoma cells to be more sensitive to the lowered tyrosine level or the toxic effects of tyrosine metabolites, resulting in the inhibition of murine B16F10 melanoma growth in mice [44, 45]. To avoid the need for daily intravenous infusions, we have prepared PEG-PLA nanocapsules containing the nanobiotechnological complex of polyhemoglobin-tyrosinase [54]. This has a much longer circulation time than the polyhemoglobin complex [47]. By using PLA instead of PEG-PLA, we can prepare PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] for intratumoral or local injection around the tumour sites or for locating at the lymph nodes that drain the area. The smaller nanocapsules can enter the melanoma cells to inhibit cell growth and attachment especially if the cells metastasize. The larger ones can act on tyrosine in the extracellular environment of the melanoma cells to convert extracellular tyrosine. They can also follow the same path as the metastasis of melanoma cells to the lymph nodes or organs to continue to act on tyrosine in the region. The diameters are in the range of 88 to 267 nm (187 ± 35 nm). This would have nanocapsules for both intracellular and extracellular functions. A range of 33 to 300 nm in diameter is also possible.

At present, two types of experiments on murine B16F10 melanoma cells were carried out. (1) Proliferation model: attached B16F10 melanoma cells were treated with PLA nanocapsules containing polyHb-Tyr or the different components. The effects on cell viability were followed. (2) Attachment model: melanoma cells were cocultured with PLA nanocapsules containing polyHb-Tyr or the different components. The effects on cell attachment were followed. The data showed that PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] could inhibit both the proliferation and attachment of melanoma cells. This is related to the enzymatic action of tyrosinase on tyrosine. This could be due to the lowered tyrosine level [17–20] or the toxic effect of products tyrosine metabolism [24, 25]. The results also showed that polyhemoglobin, one of the components of PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr], had by itself some ability to inhibit melanoma cells growth. Hemoglobin is a known nitric oxide scavenger [58] and the depletion of endogenously produced nitric oxide can inhibit melanoma proliferation and promote apoptosis [59]. As a result, polyhemoglobin in the PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] could have an additional effect on limiting the growth of melanoma cells. For intravenous use, PEG is added to PLA to form PEG-PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] resulting in much longer circulation time. The present study showed that it was also as effective as PLA nanocapsule [polyHb-Tyr] in inhibiting melanoma cells attachment.

5. Conclusion

Previously, we have reported that daily intravenous infusions of a soluble nanobiotechnological complex, polyhemoglobin-tyrosinase [polyHb-Tyr], can suppress the growth of a murine B16F10 melanoma in a mouse model [44]. In order to avoid the need for daily intravenous injections, we have now prepared two types of biodegradable nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr] with diameters in the range of 88 to 267 nanometers. One type is to increase the circulation time and decrease the frequency of injection and is based on PEG-PLA nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. The other type is to allow for intratumoural or local injection and is based on PLA nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr]. The cell culture study shows that it can inhibit the proliferation of murine B16F10 melanoma cells in the “proliferation model.” It can also inhibit the attachment of murine B16F10 melanoma cells in the “attachment model.” The component analysis shows that the enzymatic action of tyrosinase on tyrosine plays the major role in the nanocapsule-[polyHb-Tyr]. The other component, polyHb, plays a smaller role in the nanocapsules containing [polyHb-Tyr], and this is most likely due to its depletion of nitric oxide needed for melanoma cell growth.

Acknowledgments

Professor T. M. S. Chang acknowledges the operating term grant awarded to him from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 13745). Ms. Y. Wang acknowledges the scholarship award from the Chinese Scholarship Council for her Ph.D. study.

References

- 1.Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy. Nature. 2007;445(7130):851–857. doi: 10.1038/nature05661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berwick M, Erdei E, Hay J. Melanoma epidemiology and public health. Dermatologic Clinics. 2009;27(2):205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smalley KSM. Understanding melanoma signaling networks as the basis for molecular targeted therapy. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2010;130(1):28–37. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damsky WE, Rosenbaum LE, Bosenberg M. Decoding melanoma metastasis. Cancers. 2011;3(1):126–163. doi: 10.3390/cancers3010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soengas MS, Lowe SW. Apoptosis and melanoma chemoresistance. Oncogene. 2003;22(20):3138–3151. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Testori A, Rutkowski P, Marsden J, et al. Surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20:vi22–vi29. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munshi A, Kurland JF, Nishikawa T, Chiao PJ, Andreeff M, Meyn RE. Inhibition of constitutively activated nuclear factor-κB radiosensitizers human cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2004;3(8):985–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mocellin S, Pasquali S, Rossi CR, Nitti D. Interferon alpha adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(7):493–501. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheatley K, Ives N, Hancock B, Gore M, Eggermont A, Suciu S. Does adjuvant interferon-α for high-risk melanoma provide a worthwhile benefit? A meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2003;29(4):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uhlenkott CE, Huijzer JC, Cardeiro DJ, Elstad CA, Meadows GG. Attachment, invasion, chemotaxis, and proteinase expression of B16-BL6 melanoma cells exhibiting a low metastatic phenotype after exposure to dietary restriction of tyrosine and phenylalanine. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 1996;14(2):125–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00121209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elstad CA, Meadows GG, Aslakson CJ, Starkey JR. Evidence for nutrient modulation of tumor phenotype: impact of tyrosine and phenylalanine restriction. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1994;354:171–183. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0939-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris JR, Meadows GG, Massey LK, Starkey JR, Sylvester DM, Liu SY. Tyrosine- and phenylalanine-restricted formula diet augments immunocompetence in healthy humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990;51(2):188–196. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson DH, Stockton LH, Bleier JC, Acosta PB, Heymsfield SB, Nixon DW. The effect of a phenylalanine and tyrosine restricted diet on elemental balance studies and plasma aminograms of patients with disseminated malignant melanoma. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1985;41(1):73–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam TL, Wong GKY, Chow HY, et al. Recombinant human arginase inhibits the in vitro and in vivo proliferation of human melanoma by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research. 2011;24(2):366–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feun L, You M, Wu CJ, et al. Arginine deprivation as a targeted therapy for cancer. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008;14(11):1049–1057. doi: 10.2174/138161208784246199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu YM, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Meadows GG. Tyrosine and phenylalanine restriction induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in murine melanoma in vitro and in vivo. Nutrition and Cancer. 1997;29(2):104–113. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu YM, Yu ZX, Pelayo BA, Ferrans VJ, Meadows GG. Focal adhesion kinase-dependent apoptosis of melanoma induced by tyrosine and phenylalanine deficiency. Cancer Research. 1999;59(3):758–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burridge K, Turner CE, Romer LH. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125(FAK) accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: a role in cytoskeletal assembly. Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;119(4):893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu YM, Zhang H, Ding M, et al. Specific amino acid restriction inhibits attachment and spreading of human melanoma via modulation of the integrin/focal adhesion kinase pathway and actin cytoskeleton remodeling. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 2005;21(7):587–598. doi: 10.1007/s10585-004-5515-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ge X, Fu YM, Li YQ, Meadows GG. Activation of caspases and cleavage of Bid are required for tyrosine and phenylalanine deficiency-induced apoptosis of human A375 melanoma cells. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2002;403(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slominski A, Zmijewski MA, Pawelek J. L-tyrosine and L-dihydroxyphenylalanine as hormone-like regulators of melanocyte functions. Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research. 2012;25(1):14–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Wortsman J. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiological Reviews. 2004;84(4):1155–1228. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urabe K, Aroca P, Tsukamoto K, et al. The inherent cytotoxicity of melanin precursors: a revision. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1221(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fruehauf JP, Trapp V. Reactive oxygen species: an Archilles’ heel of melanoma? Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2008;8(11):1751–1757. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.11.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang TMS. Semipermeable microcapsules. Science. 1964;146(3643):524–525. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3643.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang TMS, Poznansky MJ. Semipermeable microcapsules containing catalase for enzyme replacement in acatalasaemic mice. Nature. 1968;218(5138):243–245. doi: 10.1038/218243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang TMS. The in vivo effects of semipermeable microcapsules containing L-asparaginase on 6C3HED lymphosarcoma. Nature. 1971;229(5280):117–118. doi: 10.1038/229117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourget L, Chang TMS. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase immobilized in microcapsules for the depletion of phenylalanine in plasma in phenylketonuric rat model. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1986;883(3):432–438. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmour RM, Goodyer P, Reade T, Chang TMS. Microencapsulated xanthine oxidase as experimental therapy in Lesch-Nyhan disease. The Lancet. 1989;2(8664):687–688. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90939-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poznansky MJ, Chang TMS. Comparison of the enzyme kinetics and immunological properties of catalase immobilized by microencapsulation and catalase in free solution for enzyme replacement. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1974;334(1):103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang TMS. Stablisation of enzymes by microencapsulation with a concentrated protein solution or by microencapsulation followed by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1971;44(6):1531–1536. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(71)80260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang TMS. Biodegradable semipermeable microcapsules containing enzymes, hormones, vaccines, and other biological. Journal of Bioengineering. 1976;1(1):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swi Chang TM. Therapeutic applications of polymeric artificial cells. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4(3):221–235. doi: 10.1038/nrd1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang TM. Enzyme artificial cells in substrate-dependent tumours and activation of prodrug. Artificial Cells Regenerative Medicine, Artificial Cells and Nanomedicine. 2007;1:160–194. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang TM. Artificial Cells: Biotechnology, Nanotechnology, Blood Substitutes, Regenerative Medicine, Bioencapsulation, Cell/Stem Cell Therapy. Singapore: World Science Publishers/Imperial College Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang TMS. Blood replacement with nanobiotechnologically engineered hemoglobin and hemoglobin nanocapsules. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2010;2(4):418–430. doi: 10.1002/wnan.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang TMS. Nanomedicine and Cardiovascular System. 2011. Nanobiotechnology-based blood substitutes and the cardiovascular systems in transfusion medicine; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore EE, Moore FA, Fabian TC, et al. Human polymerized hemoglobin for the treatment of hemorrhagic shock when blood is unavailable: the USA multicenter trial. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;208(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jahr JS, MacKenzie C, Pearce LB, Pitman A, Greenburg AG. HBOC-201 as an alternative to blood transfusion: efficacy and safety evaluation in a multicenter phase III trial in elective orthopedic surgery. Journal of Trauma. 2008;64(6):1484–1497. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318173a93f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linberg R, Conover CD, Shum KL, Shorr RGL. Increased tissue oxygenation and enhanced radiation sensitivity of solid tumors in rodents following polyethylene glycol conjugated bovine hemoglobin administration. In Vivo. 1998;12(2):167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han JQ, Yu MH, Dai M, Li HW, Xiu RJ, Liu Q. Decreased expression of MDR1 in PEG-conjugated hemoglobin solution combined cisplatin treatment in a tumor xenograft model. Artificial Cells Blood Substitutes and Biotechnology. 2012;40(4):239–244. doi: 10.3109/10731199.2012.663385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Agnillo F, Chang TMS. Polyhemoglobin-superoxide dismutase catalase as a blood substitute with antioxidant properties. Nature Biotechnology. 1998;16(7):667–671. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu B, Chang TMS. In vitro and in vivo effects of polyhaemoglobin-tyrosinase on murine B16F10 melanoma. Melanoma Research. 2004;14(3):197–202. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000131013.71638.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu B, Chang TMS. Effects of long-term oral administration of polymeric microcapsules containing tyrosinase on maintaining decreased systemic tyrosine levels in rats. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2004;93(4):831–837. doi: 10.1002/jps.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu WP, Chang TMS. Submicron biodegradable polymer membrane hemoglobin nanocapsules as potential blood substitutes: a preliminary report. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Immobilization Biotechnology. 1994;22(3):889–893. doi: 10.3109/10731199409117926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang TMS, Powanda D, Yu WP. Analysis of polyethylene-glycol-polylactide nano-dimension artificial red blood cells in maintaining systemic hemoglobin levels and prevention of methemoglobin formation. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Immobilization Biotechnology. 2003;31(3):231–247. doi: 10.1081/bio-120023155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu ZC, Chang TMS. Long-term effects on the histology and function of livers and spleens in rats after 33% toploading of PEG-PLA-nano artificial red blood cells. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 2008;36(6):513–524. doi: 10.1080/10731190802554224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu ZC, Chang TMS. Effects of PEG-PLA-nano artificial cells containing hemoglobin on kidney function and renal histology in rats. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology. 2008;36(5):421–430. doi: 10.1080/10731190802369763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vrignaud S, Benoit JP, Saulnier P. Strategies for the nanoencapsulation of hydrophilic molecules in polymer-based nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32(33):8593–8604. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mora-Huertas CE, Fessi H, Elaissari A. Polymer-based nanocapsules for drug delivery. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2010;385(1-2):113–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basarkar A, Devineni D, Palaniappan R, Singh J. Preparation, characterization, cytotoxicity and transfection efficiency of poly(dl-lactide-co-glycolide) and poly(dl-lactic acid) cationic nanoparticles for controlled delivery of plasmid DNA. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2007;343(1-2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shive MS, Anderson JM. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;28(1):5–24. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fustier C, Chang TM. PEG-PLA nanocapsules containing a nanobiotechnological complex of polyhemoglobin-tyrosinase for the depletion of tyrosine in melanoma: preparation and in vitro characterisation. doi: 10.4172/2155-983X.1000103. Journal of Nanomedicine Biotherapeutic Discovery. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gobeil S, Zhu X, Doillon CJ, Green MR. A genome-wide shRNA screen identifies GAS1 as a novel melanoma metastasis suppressor gene. Genes and Development. 2008;22(21):2932–2940. doi: 10.1101/gad.1714608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gupta GP, Massagué J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127(4):679–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehlen P, Puisieux A. Metastasis: a question of life or death. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(6):449–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang CH, Grimm EA. Depletion of endogenous nitric oxide enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner in melanoma cell lines. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(1):288–298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen K, Piknova B, Pittman RN, Schechter AN, Popel AS. Nitric oxide from nitrite reduction by hemoglobin in the plasma and erythrocytes. Nitric Oxide. 2008;18(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2007.09.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]