Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) has become a major health problem affecting 1.5% of the world's population over 65 years of age. As life expectancy has increased so has the occurrence of PD. The primary direct consequence of this disease is the loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra and striatum. As the intensity of motor dysfunction increases, the symptomatic triad of bradykinesia, tremors-at-rest, and rigidity occur. Progressive neurodegeneration may also impact non-DA neurotransmitter systems including cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic, often leading to the development of depression, sleep disturbances, dementia, and autonomic nervous system failure. L-DOPA is the most efficacious oral delivery treatment for controlling motor symptoms; however, this approach is ineffective regarding nonmotor symptoms. New treatment strategies are needed designed to provide neuroprotection and encourage neurogenesis and synaptogenesis to slow or reverse this disease process. The hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/c-Met receptor system is a member of the growth factor family and has been shown to protect against degeneration of DA neurons in animal models. Recently, small angiotensin-based blood-brain barrier penetrant mimetics have been developed that activate this HGF/c-Met system. These compounds may offer a new and novel approach to the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) was first described by James Parkinson in 1867 and now affects approximately 1.5% of the world's population over 65 years of age [1]. This disease is characterized by a progressive loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. The striatum is the primary projection field of these substantia nigra neurons, thus the loss of DA results in insufficient stimulation of dopaminergic D 1 and D 2 receptors throughout the striatum [2–4]. Decreased availability of DA triggers the symptomatic triad of bradykinesia, tremors-at-rest, and rigidity. The pathogenesis of PD is unclear with both genetic and environmental factors playing roles. There is evidence from animal models and PD patients that neuroinflammatory processes, triggered by reactive oxygen species, damage mitochondrial membrane permeability, enzymes, and mitochondrial genome resulting in DA cell death [5, 6]. Progressive neurodegeneration may also impact non-DA neurotransmitter systems such as cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic. This expanded neural damage adds nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disturbances, depression, dementia, and possibly autonomic nervous system failure. L-DOPA is efficacious at controlling motor symptoms in the majority of patients but is ineffective regarding nonmotor symptoms. Current treatment strategies to relieve these symptoms include DA replacement via levodopa (L-DOPA, the precursor of DA), DA receptor agonists, monoamine oxidase B inhibitors, and catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors (to protect the DA that is formed). As the disease progresses periods of decreased mobility, dyskinesia, and spontaneous involuntary movements complicate treatment [7]. These motor dysfunctions are currently treated with the DA receptor agonists, apomorphine and levodopa, and surgical techniques including pallidectomy and deep brain electrical stimulation [8–10]. Progressive neurodegeneration may also involve additional nondopaminergic neurotransmitter systems including noradrenergic, cholinergic, and serotonergic [11]. As a result, nonmotor symptoms may develop including depression, sleep disturbances, dementia, and autonomic nervous system failure [12, 13].

L-DOPA continues to be the most efficacious oral delivery treatment for the control of motor symptoms [14]. Unfortunately, L-DOPA is reasonably ineffective at combating nonmotor symptoms [12]. Thus, current research efforts are directed at controlling these additional symptoms, as well as the development of new strategies designed to offer neuroprotection and overall disease reversal benefits. Attaining the goal of slowing or reversing the rate of DA neuron loss may also result in the protection of non-DA neurotransmitter systems.

This paper focuses on a new target for the treatment of this disease, specifically the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS), and the recent discovery of its interaction with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its tyrosine kinase c-Met receptor [15, 16]. The HGF/c-Met receptor system functions as a critical survival system for motor and sensory neurons and a subset of root ganglion neurons [17–19]. This relationship offers interesting possibilities with respect to neurotransmitter systems crosstalk, suggesting that small angiotensin-based agonists and antagonists can be designed to act at the HGF/c-Met complex in place of large protein ligands. The next sections provide summaries of the RAS and HGF systems, consideration of reports describing their interaction, and the involvement of the RAS and HGF systems in PD. We conclude by presenting support for the notion that angiotensin agonists may be useful in activating the HGF/c-Met receptor system in order to provide cerebroprotection and encourage synaptogenesis in Parkinson's disease patients.

2. Brain Angiotensins and the AT1, AT2, and AT4 Receptor Subtypes

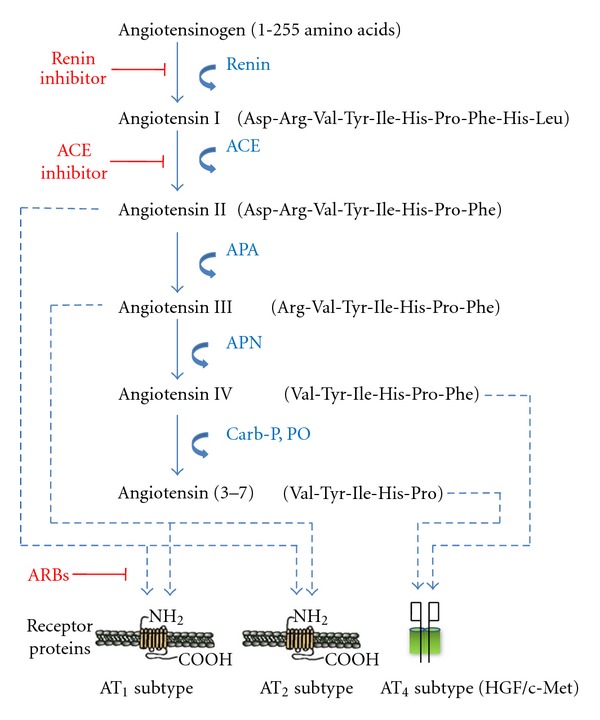

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is well known as a regulator of systemic blood pressure, body water balance, activation of sympathetic pathways, and control over vasopressin and oxytocin synthesis and release [20–22]. These functions are mediated, in part, by an independent brain RAS complete with the necessary components including angiotensinogen, renin, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), angiotensin ligands, and receptor proteins [23–26]. Following the discovery of this independent brain RAS separate from the peripheral system, three brain angiotensin receptor subtypes were identified. The first two, AT1 and AT2, are G-protein coupled and have been well described in previous review papers [15, 20, 22, 27] (Figure 1). Our laboratory discovered a third subtype, AT4, and its identity is currently a matter of controversy (see below).

Figure 1.

Description of the peptide structures and enzymes involved in the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I through shorter angiotensins. The biologically active forms include angiotensins II, III, IV, and angiotensin (3–7). The respective receptors where these angiotensins bind are indicated by arrows. The locations of action of angiotensin inhibitors are also indicated. Abbreviations: ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme; APA = aminopeptidase A; APN = aminopeptidase N; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; Carb-P = carboxy peptidase P; PO = propyl oligopeptidase.

The distribution of brain structures possessing AT1 receptor sites is reasonably consistent among the mammalian species examined using quantitative autoradiography and radioreceptor binding homogenate tissue preparations. These species include rat, mouse, hamster, dog, monkey, and human (reviewed in [28–30]). The AT1 subtype is localized in high densities within the anterior pituitary, area postrema, lateral geniculate body, inferior olivary nucleus, median eminence, nucleus of the solitary tract, the anterior ventral third ventricle region, paraventricular, preoptic and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus, subfornical organ, and ventral tegmental area. This receptor subtype is represented in the following motor related brain structures: caudate putamen, cerebellum, striatum, and substantia nigra (Table 1).

Table 1.

Predominant distributions of the three angiotensin receptor subtypes and the HGF/c-Met receptor identified in mammalian brains.

| Subtype | AT1 | AT2 | AT4 | c-Met |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | ||||

| Caudate putamen | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Cerebellum | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Globus pallidus | ++ | ++ | ||

| Nucleus accumbens | + | |||

| Periaqueductal gray | ++ | |||

| Red nucleus | + | |||

| Striatum | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Substantia nigra | ++ | + | ||

| Ventral tegmental area | ++ | ++ | ++ |

The highest densities of the AT2 site are found in the amygdala, medial geniculate body, habenula, hypoglossal nucleus, inferior colliculus, inferior olivary nucleus, locus coeruleus, striatum, thalamus, and ventral tegmental area. This receptor subtype is present in the following motor related structures: caudate putamen, cerebellum, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra (Table 1).

The AT4 receptor is distributed within a number of brain structures with notably high concentrations in the anterior pituitary, cerebral cortex, lateral geniculate body, habenula, hippocampus, inferior olivary nucleus, nucleus basalis of Meynert, periaqueductal gray, piriform cortex, superior colliculus, thalamus, and ventral tegmental area, and of particular interest caudate putamen, cerebellum, globus pallidus, nucleus accumbens, red nucleus, striatum, and substantia nigra (Table 1). Although the brain distribution of AngIV is not available, the locations of aminopeptidase A (AP-A, an aminopeptidase that converts the octapeptide AngII to the heptapeptide AngIII) and aminopeptidase N (AP-N, an aminopeptidase that converts AngIII to the hexapeptide AngIV) are suggestive given their likely co-localization with AngIV. Both AP-A and AP-N have been localized to the plasma membrane of pericytes suggesting that AngIV is found in the extracellular space surrounding microvessels in the brain [34, 35]. In support of this notion exogenous administration of AngIV has been shown to increase cerebral microcirculation [36–38]. Most relevant, Lanckmans and colleagues [39, 40] measured AngIV in the striatum using microdialysis coupled with a sensitive liquid chromatography mass spectrometry system. However, shortly following probe insertion the levels of AngIV often dropped below the detection limit of 50 pM. This was interpreted to suggest an intracellular presence for AngIV. This notion is supported by several reports indicating that within neurons AngII is converted to AngIV (80%), with smaller fractions of AngIII, Ang(1–7), and Ang(1–6) (reviewed in [41]).

Thus, of the three subtypes the AT4 receptor, colocalized with AngIV, is prominently represented in brain structures associated with motor functioning; however, to date the greatest attention has been devoted to the AT1 and AT2 receptor subtypes. Other functions associated with each angiotensin receptor subtype are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ligand activation of the AT1, AT2, and AT4 receptor subtypes influence the following functions.

| AT1 receptor subtype | |

| Vasoconstriction | |

| Aldosterone release | |

| Vasopressin release | |

| Cardiac hypertrophy | |

| Fibrosis | |

| Proliferation | |

| Inflammation | |

| Platelet aggregation | |

| Oxidative stress | |

| Endothelial disruption | |

|

| |

| AT2 receptor subtype | |

| Vasodilation | |

| Antifibrotic | |

| Antiproliferative | |

| Antihypertrophic | |

| Antithrombotic | |

|

| |

| AT4 receptor subtype | |

| Dendritic arborization | |

| Changes in blood flow | |

| Memory facilitation | |

| Protection against seizures | |

| Facilitates wound healing | |

3. Brain Hepatocyte Growth Factor/c-Met

Hepatocyte growth factor, also known as “scatter factor”, is a glycoprotein recognized as a potent mitogenic, morphogenic, and motogenic growth factor that acts via the type 1 tyrosine kinase receptor c-Met [42]. HGF was originally isolated from the liver and was shown to promote liver regeneration [43]. In 1991, Bottaro et al. [44] identified c-Met as a receptor for HGF. The c-Met receptor protein is made up of disulfide bond-linked alpha (45 kDA) and beta (145 kDa) subunits [45]. The alpha chain is extracellular while the beta chain is transmembrane. HGF dimerization precedes binding to the c-Met receptor which then undergoes phosphorylation. Once phosphorylated, the tyrosine residues of the beta subunit serve as docking sites for downstream signaling mediators including the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (P13K) pathway [46, 47]. This HGF/c-Met signaling is regulated by the activator, hepatocyte growth factor A (HGFA), and its inhibitor, HGFAI. HGFA is a protease that acts on the precursor protein and produces active HGF. In contrast, HGFAI blocks the activation of HGFA [48]. c-Met has been shown to play a role in multiple types of cancer (reviewed in [49, 50]), blunt neurodegenerative changes [51], facilitate long-term potentiation (LTP [52]), contribute to learning and memory consolidation [52–56], and may play a role in Alzheimer's disease [57, 58]. Also, inactivation of c-Met in the embryonic proliferative zones of mice results in an increase in parvalbumin-expressing cells in the dentate gyrus, a loss of these cells in the CA3 field, with an overall loss of calretinin-expressing cells throughout the hippocampus [59]. These results highlight the importance of c-Met with regard to appropriate hippocampal development. Lan et al. [60] have shown that HGF regulates proliferation and migration of dopaminergic progenitor cells isolated from fetal striatum. These cells were capable of differentiating into functioning neurons with the ability to release DA. Schwartz and colleagues [61] have reported that human embryonic stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons increased expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (a DA neuron marker) when any one of several growth factors were added to the cell culture including HGF, stromal cell-derived factor-1α, and vascular endothelial growth factor. The authors concluded that these growth factors may be of potential use to induce DA cellular differentiation of pluripotent human stem cells.

There have been reports of elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid HGF in PD patients as compared with normal controls [62, 63]. Along these lines, several researchers have suggested the use of HGF as a therapeutic agent for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and neuroimmune diseases [19, 64], ischemia-stroke [53, 65], neurodegenerative diseases [66], and CNS neuron survival [67–69]. Recently, Koike and colleagues [70] utilized the 6-hydroxy dopamine (6-OHDA) rat model of PD to test the hypothesis that transfected human HGF injected into the striatum could protect DA neurons. 6-OHDA lesioned rats treated with lacZ plasmid lost more than 90% of their DA neurons. In contrast, 70% of the DA neurons survived in rats transfected with HGF. Thus, over expression of HGF protected DA neurons in these 6-OHDA lesioned rats. These results are important for two reasons: (1) a gene therapy approach designed to overexpress HGF may be efficacious when applied to PD patients and (2) these results indicate that a drug designed to facilitate HGF expression in PD patients may offer neuroprotection from ongoing DA neurodegeneration.

4. Interaction between Angiotensin IV and the HGF/c-Met System

Although the identity of the AT4 receptor remains controversial, this receptor protein has been partially sequenced as insulin-regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP [71, 72]). The distribution of brain IRAP mRNA and protein matches that of the AT4 receptor protein as indicated by [125I] AngIV-radioligand binding assay [71, 73]. IRAP is a member of type 2 transmembrane proteins of the gluzincin aminopeptidase family [74] which includes homologous aminopeptidases such as aminopeptidases A and N. IRAP is capable of cleaving the N-terminal amino acid from a number of peptides including met-enkephalin, dynorphin, oxytocin, arginine-vasopressin, lysine-bradykinin, neurokinin A, somatostatin, neuromedin B, and cholecystokinin-8 [75–77]. Thus, IRAP has been variously identified as oxytocinase, cystinyl aminopeptidase, placental leucine aminopeptidase, gp 160, or vp 165 depending on its independent cloning (reviewed in [78]). The key substrates acted upon by this enzyme are thought to be arginine vasopressin and oxytocin [72, 79]. IRAP consists of 1025 amino acid residues with a 110 amino acid N-terminal hydrophilic intracellular domain that includes two dileucine motifs. The hydrophobic transmembrane domain consists of 22 amino acids that continues with an 893 amino acid C-terminal extracellular domain associated with its catalytic site. The catalytic site is composed of a GAMEN motif and includes the HEXXH(X)18 Zn2+-binding motif [80–82].

Recently our laboratory has challenged the “AT4 receptor is IRAP” hypothesis. This challenge is based on our search for a molecular target with structural homology to angiotensin IV and physiological functions in agreement with those identified for the AngIV/AT4 system. We discovered a partial match with the antiangiogenic protein angiostatin and the related plasminogen family member HGF. The functions associated with the HGF/c-Met system overlap with those mediated by the AngIV/AT4 system including facilitated memory consolidation, augmented neurite outgrowth, hippocampal LTP and calcium signaling, dendritic arborization, facilitation of cerebral blood flow and cerebroprotection, seizure protection, and facilitated wound healing (Table 3; reviewed in [15, 16]). This led to the hypothesis that AngIV analogues may exert their activity via the HGF/c-Met system. In a recent investigation we reported that the AT4 receptor antagonist, Norleual-AngIV, inhibited HGF binding to c-Met and HGF-dependent signaling, proliferation, invasion, and scattering [83]. The mechanism of action regarding Norleual-AngIV's ability to act as a c-Met receptor antagonist is by inhibiting the dimerization of HGF which is a prerequisite to c-Met binding [84, 85]. These results strongly suggest that the biological effects of AngIV, and AngIV analogues, are mediated through the HGF/c-Met system.

Table 3.

Summary of overlapping functions associated with the AngIV/AT4 receptor subtype and the HGF/c-Met receptor.

| Function | AngIV/AT4

receptor subtype |

HGF/c-Met receptor |

|---|---|---|

| Memory facilitation | [30, 86–92] | [51, 53, 54, 56, 69] |

| Hippocampal LTP, Ca++ signaling | [93–96] | [52] |

| Dendritic arborization | [97] | [98–102] |

| Cerebral blood flow | [36, 38, 103] | [51, 53, 54, 65, 104–106] |

| Seizure protection | [107–109] | [12] |

| Parkinson's disease | [110] | [60–63, 70] |

| Angiogenesis and PAI-1 expression | [22, 83, 111, 112] | [65, 113, 114] |

| Neurite outgrowth | [115] | [114, 116, 117] |

Several observations and research findings are relevant to the hypothesis that the AT4 receptor subtype is HGF/c-Met. (1) As mentioned earlier, heavy brain distributions of the AT4 receptor subtype are located in neocortex, piriform cortex, hippocampus, nucleus basalis of Meynert, amygdala, cerebellum, caudate putamen, globus pallidus, striatum, and substantia nigra, consistent with expectations concerning brain locations for a receptor acting as a mediator of cognitive and motor processing [28, 31, 118, 119]. Partial determination of brain c-Met receptor distributions generally agree with this pattern [120, 121]. (2) The AT4 receptor subtype's ability to facilitate LTP, separate from NMDA-dependent LTP, suggests a nonglutamatergic signaling pathway [93]. (3) The finding that facilitation of the AT4 receptor subtype results in increased internalization of calcium via at least three different calcium channels suggests a rapid and salient cell signaling event [93] and agrees with the observation that HGF-induced responses also depend upon the internalization of calcium [98]. (4) Conversion of AngII to AngIV appears to be necessary for AngII-induced DA release in the striatum [122], and acetylcholine release in the hippocampus [123]. (5) The coupling of increased neural intracellular calcium with matrix metalloproteinases released into the extracellular space suggests a neural plasticity function [124, 125]. (6) Recent neural imaging work completed in our laboratory (see below [97]) indicates that Nle1-AngIV stimulates dendritic spine numbers and size in the hippocampus, as well as overall dendritic arborization, suggesting a plausible synaptogenesis mechanism to explain the ability of these molecules to enhance synaptic plasticity and connectivity among neurons. In agreement, HGF has been shown to increase dendritic arborization in hippocampal neurons in culture [98].

Members of our research group have focused attention on understanding how AT4 receptor agonists and antagonists facilitate and interfere with, respectively, learning and memory. We determined that the metabolically resistant agonist Nle1-AngIV significantly facilitated LTP in the CA1 field of hippocampal slices [94], while both AngIV, and Nle1AngIV, enhanced LTP in the dentate gyrus in vivo [95]. Pretreatment with the AT4 receptor antagonist Divalinal-AngIV prior to tetanization significantly disrupted the maintenance phase of LTP. The Nle1-AngIV facilitation of LTP was shown to be dependent on increased intracellular calcium via L- and T-type voltage-dependent calcium channels [93]. The ability of these agonists to promote Ca2+ entry, particularly via L-type channels, suggested the potential mechanism of altered dendritic arborization [126, 127]. We next examined the ability of AT4 agonists to facilitate dendritic arborization in disassociated rat hippocampal neurons labeled with mRFP-bactin to visualize the cytoskeleton, including the spines. Quantitative analysis from neurons exposed to Nle1-AngIV for 5 days indicated an increased number of dendritic spines per dendrite, accompanied by an expansion in dendritic arborization [97]. The above observations support the hypothesis that the primary mechanism underlying memory facilitation by AngIV and its analogues may be the ability to enhance synaptic communication and neural activity.

These Nle1-AngIV-induced increases in dendritic arborization are consistent with the hypothesis that AT4 receptor ligands alter HGF docking at the c-Met receptor. There are several reports indicating that HGF and c-Met are neuronally expressed in several brain structures including the neocortex and hippocampus [120] and appear in high densities at excitatory synapses within the hippocampus [121]. Activation of the c-Met receptor by HGF promotes neurite outgrowth [128] and dendritic branching by cortical neurons in sliced cultures [99]. The complexity of the dendritic branching could be attenuated with anti-HGF antibodies [99]. Recently, Tyndall and colleagues [98] reported that HGF increased the size and complexity of dendritic arborization in dissociated hippocampal neurons in culture. This facilitation could be blocked by pretreatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist, DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV). It was further determined that this HGF effect is dependent on elevations in intracellular calcium and accompanying increases in autophosphorylation of CaMKII. These results suggest that Ca2+-dependent processing underlies HGF's ability to increase dendritic arborization and are consistent with our findings indicating increased hippocampal neuronal intracellular calcium with Nle1-AngIV treatment and facilitated hippocampal dendritic arborization. Pretreatment of cultured hippocampal neurons with an AT4 receptor antagonist inhibited this Nle1-AngIV-induced arborization. Recently our laboratory has used a tritiated small molecule HGF analogue to further identify the locations of brain HGF/c-Met receptors [129]. Reasonably high concentrations of HGF/c-Met were measured in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, thalamus, hypothalamus, striatum, and lower brain stem structures.

5. A Link between the Brain Angiotensin System and Parkinson's Disease

The potential relationship between the brain RAS and PD was initially suggested by Allen and colleagues [130]. These investigators measured decreased angiotensin receptor binding in the substantia nigra and striatum in post mortem brains of PD patients. A number of studies support an important role for ACE in this disease. ACE is present in the nigra-striatal pathway and basal ganglia structures [131–133]. Parkinson's disease patients treated with the ACE inhibitor perindopril revealed improved motor responses to the DA precursor 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine [134]. Relative to this treatment with perindopril, elevated striatal DA levels have been measured in mice [135]. In addition, ACE has been shown to metabolize bradykinin and thus modulate inflammation [136], a contributing factor in PD. Activation of the AT1 receptor subtype by AngII promotes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent oxidases, a significant source of reactive oxygen species [137, 138]. Treatment with ACE inhibitors has been shown to offer protection against the loss of DA neurons in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) animal models [139, 140], as well as the 6-OHDA rat model [141]. The likely mechanism underlying this ACE inhibitor-induced protection is a reduction in the synthesis of AngII acting at the AT1 receptor subtype (reviewed in [142]). It is known that AngII binding at the AT1 subtype activates the NADPH oxidase complex, thus providing a major source of reactive oxygen species [143, 144]. Further, activation of the AT1 receptor results in the stimulation of the NF-κB signal transduction pathway facilitating the synthesis of chemokine, cytokines, and adhesion molecules, all important in the migration of inflammatory cells into regions of tissue injury [145].

Given the above reports, it follows that if AngII activation of the AT1 receptor subtype results in facilitation of the NADPH oxidase complex, and thus formation of free radicals, then blockade of the AT1 receptor should serve a protective function. This appears to be the case. Treatment with AT1 receptor antagonists, known as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), protects DA neurons in both 6-OHDA [33, 146–148] and MPTP animal models [144, 149, 150]. ARBs have been shown to reduce the formation of NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species following administration of 6-OHDA [33]. While the risk of developing PD is reduced with the use of calcium channel blockers to control hypertension, the influence of ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and ARBs is not clear [151]. Ascherio and Tanner [152] have pointed out several shortcomings in the above study by Becker and colleagues and suggested that their analysis be redone to include a time frame of up to two years prior to the onset of PD symptoms. Of relevance to this issue, there is the occasional PD patient in which an ARB (Losartan) has been reported to exacerbate the motor dysfunctions [153]. While on Losartan, this patient experienced severe bradykinesia accompanied by frequent episodes of freezing.

The AT2 receptor subtype is present in several fetal tissues including uterus, ovary, adrenal gland, heart, vascular endothelium, kidney, and brain (particularly neocortex and hippocampus) [20, 154–157]. As the animal matures, the expression of the AT2 receptor decreases. It appears that adult mammalian brain levels of this receptor in the striatum and substantia nigra are reasonably low [22, 158]. The AT2 receptor has been linked with cell proliferation, differentiation, and tissue regeneration [159–162]. The results from a study utilizing mesencephalic precursor cells indicated that AngII, acting at the AT2 receptor, facilitated differentiation of precursor cells into DA neurons [163]. Along these lines, activation of the AT2 receptor has been shown to inhibit NADPH oxidase activation [164]. However, Rodriguez-Pallares et al. [165] found that AngII treatment of the 6-OHDA lesioned rat increased DA cell death. This could be due to the much greater numbers of brain AT1 receptors, as compared with AT2 receptors, such that the beneficial effects of AT2 receptor activation were overwhelmed by AT1 activation. Finally, the expression of AT2 receptors in PD patients appears to be decreased in the caudate nucleus but is unchanged in the substantia nigra and putamen [166].

Recent studies using several animal models indicate that basal ganglia structures possess a local RAS that evidences increased activity during dopaminergic degeneration [167–169]. For example, reserpine-induced decreases in DA resulted in a significant increase in the expression of AT1 and AT2 receptors [170]. A similar pattern was seen with 6-OHDA-induced DA denervation, with a decrease in receptor expression when L-dopa was given. These results are important in that a clear interaction between the RAS and the DA system appears to be present in basal ganglia structures. Related to this, Rodriguez-Perez and colleagues [171] produced dopaminergic degeneration via intrastriatal 6-OHDA injection and noted a significant decrease in dopaminergic neurons in ovariectomized rats. This neuron loss was attenuated by treatment with the AT1 receptor antagonist candesartan, or estrogen replacement. Estrogen replacement also resulted in a downregulation of AT1 receptors and NADPH complex in the substantia nigra, accompanied by an upregulation of the AT2 receptor subtype. These results indicate an important relationship among estrogen levels, brain DA receptors, and the RAS. An increase in the expression of AT1 receptors and decreased expression of AT2 receptors has been reported in aged rats [172]. This observation is of major importance given the potentially deleterious consequences of AT1 receptor activation on basal ganglia structures.

Recently the Rodriquez-Perez research group [173] reported that chronic hypoperfusion in rats resulted in a reduction in striatal DA levels, accompanied by a large decline in dopaminergic neurons and striatal terminals. This DA neuron loss was countered by orally administered candesartan. In addition, AT1 receptor expression was highest in the substantia nigra, while AT2 expression was lower in rats that experienced chronic hypoperfusion as compared with controls. Again these effects could be attenuated by candesartan. Taken together, these findings argue that inhibition of AT1 receptor activity should serve a neuroprotective role in PD.

The potential involvement of AngIV in Parkinson's disease has been initially investigated [110]. A genetic in vitro PD model was used consisting of the α-synuclein overexpression of the human neuroglioma H4 cell line. Results indicated a significant reduction in α-synuclein-induced toxicity with Losartan treatment combined with the AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319, in the presence of AngII. Under these same conditions, AngIV was only moderately effective. However, these researchers did not use a metabolically stable AngIV analogue, nor did they confirm effects with an AT4 receptor antagonist in combination with AngII or AngIV.

Overall, experimental work suggests that treatment with an ARB may offer some protection against the risk of developing PD. However, much additional work must be completed to better understand the relationship among brain angiotensin receptors, ligands, inflammation, and reactive oxygen species as related to PD.

6. Relationship among Angiotensins, HGF, and Parkinson's Disease

Aging is one of the major risk factors predisposing individuals to neurodegenerative diseases [174–177]. The neurodegeneration accompanying aging is dependent in part upon oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and microglial NADPH oxidase activity. Each is of significant importance regarding DA neuron loss [178, 179]. Activation of AT1 receptors by AngII has been shown to facilitate DA neuron degeneration by activating microglial NADPH oxidase [147]. The activation of AT1 receptors by AngII failed to cause DA neuron degeneration when microglial cells were absent [180]. Of related importance, Zawada and colleagues [181] recently reported that nigral dopaminergic neurons respond to neurotoxicity-induced superoxide in two waves. First, a spike in mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide was measured three hours following treatment with an MPTP metabolite (MPP+). Second, by twenty-four hours following treatment, hydrogen peroxide levels were further elevated. Treatment with Losartan suppressed this nigral superoxide production suggesting a potentially important role for ARBs in the treatment of PD. Further, AngII binding at the AT1 receptor increased DA neuron degeneration initiated by subthreshold doses of DA neurotoxins by stimulating intraneuronal levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neuroinflammation by activation of microglial NADPH oxidase [37, 144, 182–184].

From the above observations, it follows that AT1 receptor blockade should have a neuroprotective effect on DA neurons in PD patients as demonstrated in animal models [149]. Less obvious is the likelihood that AT1 receptor blockade results in accumulating levels of AngII which is converted to AngIII and then to AngIV. This conversion cascade has been shown to occur intracellularly [41]. In fact, this conversion of AngII appears to be necessary for DA release to occur in the striatum [122]. Thus, an intriguing alternative explanation of these AT1 receptor antagonist results is that the increased endogenous levels of AngIV facilitate activation of the HGF/c-Met receptor system and neuroprotection of DA neurons. In this way, AngIV may act in combination with AT1 receptor blockade to protect DA neurons. Our laboratory has offered evidence that AngIV, and AngIV analogues, are capable of acting to facilitate HGF/c-Met activity [97]. Support for this claim is presented in several recent reports. First we found that the action of AT4 receptor antagonists depends on inhibiting the HGF/c-Met receptor system by binding to and blocking HGF dimerization [83, 84]. In contrast, AT4 receptor agonists facilitate cognitive processing and synaptogenesis by acting as mimics of the dimerization domain of HGF (hinge region) [85]. This work has culminated in the synthesis of a small molecule AT4 receptor agonist capable of penetrating the blood-brain barrier and facilitating cognitive processing presumably by increasing synaptogenesis. This small molecule (MM-201) has a Kd for HGF ≈ 13 picomolar [129]. This AngIV-HGF/c-Met interaction could explain earlier reports indicating that activation of the AT4 receptor facilitates cerebral blood flow and neuroprotection [36, 38, 103].

In agreement with the above findings, HGF has been shown to positively impact ischemic-induced injuries such as cardiac [185] and hind limb ischemia [104, 105]. HGF has also been shown to eliminate hippocampal neuronal cell loss in transient global cerebral ischemic gerbils [65], and transient focal ischemic rats [106]. Date and colleagues [54] have reported HGF-induced improvements in escape latencies by microsphere embolism-cerebral ischemic rats using a circular water maze task. These authors measured reduced damage to cerebral endothelial cells in ischemic animals treated with HGF. Shimamura et al. [51] have recently shown that over-expression of HGF following permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion resulted in significant recovery of performance in the Morris water maze and passive avoidance conditioning tasks. Treatment with HGF was also found to increase the number of arteries in the neocortex some 50 days following the onset of ischemia.

In sum, these results suggest a role for the HGF/c-Met receptor system in cerebroprotection and are consistent with the notion that AngIV increases blood flow by an NO-dependent mechanism [37]. In support of this hypothesis, a report by Faure et al. [113] indicated that increasing doses of AngIV via the internal carotid artery significantly decreased mortality and cerebral infarct size in rats twenty-four hours following embolic stroke due to the intracarotid injection of calibrated microspheres. Pretreatment with the AT4 receptor antagonist Divalinal-AngIV, or Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), abolished this protective effect. Sequential cerebral autoradiography indicated that AngIV caused the redistribution of blood flow to ischemic areas within a few minutes. Thus, AngIV may yield its cerebral protective effect against acute cerebral ischemia via an intracerebral-hemodynamic c-Met receptor-mediated NO-dependent mechanism. Should these relationships hold, then a metabolically stable blood-brain barrier penetrant small molecule compound that activates the HGF/c-Met system could prove highly efficacious in the treatment of PD.

7. Conclusion

Parkinson's disease is a major neurodegenerative disease that is increasing in patient numbers world wide as populations live longer. New treatment strategies are needed to slow or reverse this disease process. The HGF/c-Met receptor system may offer neuroprotection to dopaminergic neurotransmitter pathways. However, the direct use of HGF has at least two major problems: (1) HGF is a large heterodimeric protein that is very expensive to produce; (2) as a large protein, HGF does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier and thus cannot reach brain locations where neurodegeneration is occurring. We have discovered that the small peptide AngIV, and its analogues, cause HGF dimerization which is a prerequisite to binding and activation of the c-Met receptor [42]. HGF has been shown to be intimately involved in cell survival, proliferation, migration, and differentiation [186–188] and blunts neurodegenerative influences [51]. The availability of small molecule HGF mimetics represents a significant advantage over the use of large HGF analogues to accomplish the treatment goal of slowing or reversing PD-induced neurodegeneration. It remains to be seen whether long-term treatment of PD patient is possible and efficacious using small molecule HGF mimetics.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this paper was supported by a Michael J. Fox Foundation grant to J. W. Harding, a grant from the Edward E. and Lucille I. Lainge Endowment for Alzheimer's Research Fund to J. W. Wright, and funds provided for medical and biological research by the State of Washington Initiative Measure no. 171.

References

- 1.Olanow CW, Stern MB, Sethi K. The scientific and clinical basis for the treatment of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;72(21, supplement 4):S1–S136. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a1d44c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O. Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system. Klinische Wochenschrift. 1960;38:1236–1239. doi: 10.1007/BF01485901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schapira AHV. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Neurologic Clinics. 2009;27(3):583–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welchko RM, Leveque XT, Dunbar GL. Genetic rat models of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/128356.128356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tufekci KU, Genc K, Genc S. The endotoxin-induced neuroinflammation model of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease. 2011;2011:25 pages. doi: 10.4061/2011/487450.487450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witte ME, Geurts JJG, de Vries HE, van der Valk P, van Horssen J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: a potential link between neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Mitochondrion. 2010;10(5):411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsden CD. Basal ganglia disease. The Lancet. 1982;2(8308):1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92797-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, Valkmann J, Schafer H, Botzel K. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(9):896–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia Ruiz PJ. Efficacy of long-term continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion in advanced Parkinson's disease with motor fluctuations: a multicenter study. Movement Disorders. 2008;23(8):1130–1136. doi: 10.1002/mds.22063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyholm D, Nilsson Remahl AIM, Dizdar N, et al. Duodenal levodopa infusion monotherapy vs oral polypharmacy in advanced Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64(2):216–223. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149637.70961.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meissner WG, Frasier M, Gasser T, et al. Priorities in Parkinson’s disease research. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2011;10(5):377–393. doi: 10.1038/nrd3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhuri KR, Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2009;8(5):464–474. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhuri KR, Odin P, Antonini A, Martinez-Martin P. Parkinson’s disease: the non-motor issues. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2011;17(10):717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipski J, Nistico R, Berretta N, Guatteo E, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. L-DOPA: a scapegoat for accelerated neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease? Progress in Neurobiology. 2011;94(4):389–407. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright JW, Harding JW. Brain renin-angiotensin—a new look at an old system. Progress in Neurobiology. 2011;95(1):49–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright JW, Harding JW. The brain renin-angiotensin system: a diversity of functions and implications for CNS diseases. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1102-2. Pflügers Archives. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebens A, Brose K, Leonardo ED, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor is an axonal chemoattractant and a neurotrophic factor for spinal motor neurons. Neuron. 1996;17(6):1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maina F, Klein R. Hepatocyte growth factor, a versatile signal for developing neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2(3):213–217. doi: 10.1038/6310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun W, Funakoshi H, Nakamura T. Localization and functional role of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its receptor c-met in the rat developing cerebral cortex. Molecular Brain Research. 2002;103(1-2):36–48. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2000;52(3):415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips MI. Functions of angiotensin in the central nervous system. Annual Review of Physiology. 1987;49:413–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright JW, Harding JW. Important roles for angiotensin III and IV in the brain renin- angiotensin system. Brain Research Reviews. 1997;25(1):96–124. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganten D, Boucher R, Genest J. Renin activity in brain tissue of puppies and adult dogs. Brain Research. 1971;33(2):557–559. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganten D, Marquez-Julio A, Granger P, et al. Renin in dog brain. The American Journal of Physiology. 1971;221(6):1733–1737. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lippoldt A, Paul M, Fuxe K, Ganten D. The brain renin-angiotensin system: molecular mechanisms of cell to cell interaction. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 1995;17(1-2):251–266. doi: 10.3109/10641969509087069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips MI, Speakman EA, Kimura B. Levels of angiotensin and molecular biology of the tissue renin angiotensin systems. Regulatory Peptides. 1993;43(1-2):1–20. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90403-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saavedra JM. Brain and pituitary angiotensin. Endocrine Reviews. 1992;13(2):329–380. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-2-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chai SY, Bastias MA, Clune EF, et al. Distribution of angiotensin IV binding sites (AT4 receptor) in the human forebrain, midbrain and pons as visualised by in vitro receptor autoradiography. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2000;20(3-4):339–348. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Bohlen und Halbach O. Angiotensin IV in the central nervous system. Cell and Tissue Research. 2003;311(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright JW, Harding JW. The brain angiotensin system and extracellular matrix molecules in neural plasticity, learning, and memory. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;72(4):263–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gard PR. The role of angiotensin II in cognition and behaviour. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;438(1-2):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright JW, Krebs LT, Stobb JW, Harding JW. The angiotensin IV system: functional implications. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 1995;16(1):23–52. doi: 10.1006/frne.1995.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rey P, Lopez-Real A, Sanchez-Iglesias S, Muñoz A, Soto-Otero R, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Angiotensin type-1-receptor antagonists reduce 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity for dopaminergic neurons. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28(4):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healy DP, Wilk S. Localization of immunoreactive glutamyl aminopeptidase in rat brain. II. Distribution and correlation with angiotensin II. Brain Research. 1993;606(2):295–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90997-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunz J, Krause D, Kremer M, Dermietzel R. The 140-kDa protein of blood-brain barrier-associated pericytes is identical to aminopeptidase N. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;62(6):2375–2386. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62062375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kramár EA, Harding JW, Wright JW. Angiotensin II- and IV-induced changes in cerebral blood flow roles of AT1 AT2, and AT4 receptor subtypes. Regulatory Peptides. 1997;68(2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(96)02116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramár EA, Krishnan R, Harding JW, Wright JW. Role of nitric oxide in angiotensin IV-induced increases in cerebral blood flow. Regulatory Peptides. 1998;74(2-3):185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naveri L, Stromberg C, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin IV reverses the acute cerebral blood flow reduction after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1994;14(6):1096–1099. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanckmans K, Stragier B, Sarre S, Smolders I, Michotte Y. Nano-LC-MS/MS for the monitoring of angiotensin IV in rat brain microdialysates: limitations and possibilities. Journal of Separation Science. 2007;30(14):2217–2224. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanckmans K, Sarre S, Smolders I, Michotte Y. Use of a structural analogue versus a stable isotope labeled internal standard for the quantification of angiotensin IV in rat brain dialysates using nano-liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2007;21(7):1187–1195. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stragier B, De Bundel D, Sarre S, et al. Involvement of insulin-regulated aminopeptidase in the effects of the renin-angiotensin fragment angiotensin IV: a review. Heart Failure Reviews. 2008;13(3):321–337. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma PC, Maulik G, Christensen J, Salgia R. c-Met: structure, functions and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2003;22(4):309–325. doi: 10.1023/a:1023768811842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakamura T, Mizuno S. The discovery of Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and its significance for cell biology, life sciences and clinical medicine. Proceedings of the Japan Academy B. 2010;86(6):588–610. doi: 10.2183/pjab.86.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bottaro DP, Rubin JS, Faletto DL, et al. Identification of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor as the c-met proto-oncogene product. Science. 1991;251(4995):802–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1846706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shinomiya N, Vande Woude GF. Suppression of met expression: a possible cancer treatment. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(14):5085–5090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosário M, Birchmeier W. How to make tubes: signaling by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Trends in Cell Biology. 2003;13(6):328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tulasne D, Foveau B. The shadow of death on the MET tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2008;15(3):427–434. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zachow R, Uzumcu M. The hepatocyte growth factor system as a regulator of female and male gonadal function. Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;195(3):359–371. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comoglio PM, Giordano S, Trusolino L. Drug development of MET inhibitors: targeting oncogene addiction and expedience. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7(6):504–516. doi: 10.1038/nrd2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang WG, Martin TA, Parr C, Davies G, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor, its receptor, and their potential value in cancer therapies. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2005;53(1):35–69. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimamura M, Sato N, Waguri S, et al. Gene transfer of hepatocyte growth factor gene improves learning and memory in the chronic stage of cerebral infarction. Hypertension. 2006;47(4):742–751. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000208598.57687.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akimoto M, Baba A, Ikeda-Matsuo Y, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor as an enhancer of nmda currents and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2004;128(1):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Date I, Takagi N, Takagi K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor attenuates cerebral ischemia-induced learning dysfunction. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;319(4):1152–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Date I, Takagi N, Takagi K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor improved learning and memory dysfunction of microsphere-embolized rats. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;78(3):442–453. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tada T, Zhan H, Tanaka Y, Hongo K, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Intraventricular administration of hepatocyte growth factor treats mouse communicating hydrocephalus induced by transforming growth factor β1. Neurobiology of Disease. 2006;21(3):576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeo S, Takagi N, Takagi K. Ischemic brain injury and hepatocyte growth factor. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2007;127(11):1813–1823. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.127.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma SK. Hepatocyte growth factor in synaptic plasticity and Alzheimer’s disease. The Scientific World Journal. 2010;10:457–461. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsuboi Y, Kakimoto K, Nakajima M, et al. Increased hepatocyte growth factor level in cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2003;107(2):81–86. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martins GJ, Plachez C, Powell EM. Loss of embryonic MET signaling alters profiles of hippocampal interneurons. Developmental Neuroscience. 2007;29(1-2):143–158. doi: 10.1159/000096219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lan F, Xu J, Zhang X, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor promotes proliferation and migration in immortalized progenitor cells. NeuroReport. 2008;19(7):765–769. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282fdf69e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwartz CM, Tavakoli T, Jamias C, et al. Stromal factors SDF1α, sFRP1, and VEGFD induce dopaminergic neuron differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2012;90(7):1367–1381. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salehi Z, Rajaei F. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2010;17(12):1553–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsuboi Y, Kakimoto K, Akatsu H, Daikuhara Y, Yamada T. Hepatocyte growth factor in cerebrospinal fluid in neurologic disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2002;106(2):99–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Funakoshi H, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF): neurotrophic functions and therapeutic implications for neuronal injury/diseases. Current Signal Transduction Therapy. 2011;6(2):156–167. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyazawa T, Matsumoto K, Ohmichi H, Katoh H, Yamashima T, Hakamura T. Protection of hippocampal neurons from ischemia-induced delayed neuronal death by hepatocyte growth factor: a novel neurotrophic factor. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1998;18(4):345–348. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199804000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimamura M, Sato N, Morishita R. Experimental and clinical application of plasmid DNA in the field of central nervous diseases. Current Gene Therapy. 2011;11(6):491–500. doi: 10.2174/156652311798192833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamanoue M, Takemoto N, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Nakajima K, Kohsaka S. Neurotrophic effect of hepatocyte growth factor on central nervous system neurons in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1996;43(5):554–564. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960301)43:5<554::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koike H, Morishita R, Iguchi S, et al. Enhanced angiogenesis and improvement of neuropathy by cotransfection of human hepatocyte growth factor and prostacyclin synthase gene. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17(6):779–781. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0754fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakamura T, Nishizawa T, Hagiya M, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of human hepatocyte growth factor. Nature. 1989;342(6248):440–443. doi: 10.1038/342440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koike H, Ishida A, Shimamura M, et al. Prevention of onset of Parkinson’s disease by in vivo gene transfer of human hepatocyte growth factor in rodent model: a model of gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Gene Therapy. 2006;13(23):1639–1644. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Albiston AL, McDowall SG, Matsacos D, et al. Evidence that the angiotensin IV (AT4) receptor is the enzyme insulin-regulated aminopeptidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(52):48623–48626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallis MG, Lankford MF, Keller SR. Vasopressin is a physiological substrate for the insulin-regulated aminopeptidase IRAP. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;293(4):E1092–E1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00440.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fernando RN, Larm J, Albiston AL, Chai SY. Distribution and cellular localization of insulin-regulated aminopeptidase in the rat central nervous system. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;487(4):372–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.20585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rogi T, Tsujimoto M, Nakazato H, Mizutani S, Tomoda Y. Human placental leucine aminopeptidase/oxytocinase: a new member of type II membrane-spanning zinc metallopeptidase family. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(1):56–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herbst JJ, Ross SA, Scott HM, et al. Insulin stimulates cell surface aminopeptidase activity toward vasopressin in adipocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272(4):E600–E606. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.4.E600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lew RA, Mustafa T, Ye S, McDowall SG, Chai SY, Albiston AL. Angiotensin AT4 ligands are potent, competitive inhibitors of insulin regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP) Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;86(2):344–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matsumoto H, Nagasaka T, Hattori A, et al. Expression of placental leucine aminopeptidase/oxytocinase in neuronal cells and its action on neuronal peptides. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;268(11):3259–3266. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Bundel D, Smolders I, Vanderheyden P, Michotte Y. Ang II and Ang IV: unraveling the mechanism of action on synaptic plasticity, memory, and epilepsy. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2008;14(4):315–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Albiston AL, Fernando RN, Yeatman HR, et al. Gene knockout of insulin-regulated aminopeptidase: loss of the specific binding site for angiotensin IV and age-related deficit in spatial memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2010;93(1):19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kandror KV, Yu L, Pilch PF. The major protein of GLUT4-containing vesicles, gp160, has aminopeptidase activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(49):30777–30780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keller SR, Scott HM, Mastick CC, Aebersold R, Lienhard GE. Cloning and characterization of a novel insulin-regulated membrane aminopeptidase from Glut4 vesicles. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(40):23612–23618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ross SA, Scott HM, Morris NJ, et al. Characterization of the insulin-regulated membrane aminopeptidase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(6):3328–3332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamamoto BJ, Elias PD, Masino JA, et al. The angiotensin IV analog Nle-Tyr-Leu-ψ-(CH2-NH2)3-4-His-Pro-Phe (Norleual) can act as a hepatocyte growth factor/c-met inhibitor. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;333(1):161–173. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.161711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kawas LH, Yamamoto BJ, Wright JW, Harding JW. Mimics of the dimerization domain of hepatocyte growth factor exhibit anti-met and anticancer activity. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;339(2):509–518. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawas LH, McCoy AT, Yamamoto BJ, Wright JW, Harding JW. Development of angiotensin IV analogs as hepatocyte growth factor/Met modifiers. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2012;340(3):539–548. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.188136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Albiston AL, Mustafa T, McDowall SG, Mendelsohn FAO, Lee J, Chai SY. AT4 receptor is insulin-regulated membrane aminopeptidase: potential mechanisms of memory enhancement. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;14(2):72–77. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Braszko JJ. D2 dopamine receptor blockade prevents cognitive effects of Ang IV and des-Phe6 Ang IV. Physiology and Behavior. 2006;88(1-2):152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Braszko JJ, Kupryszewski G, Witczuk B, Wisniewski K. Angiotensin II-(3-8)-hexapeptide affects motor activity, performance of passive avoidance and a conditioned avoidance response in rats. Neuroscience. 1988;27(3):777–783. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Braszko JJ, Walesiuk A, Wielgat P. Cognitive effects attributed to angiotensin II may result form its conversion to angiotensin IV. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2006;7(3):168–174. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2006.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Olson ML, Olson EA, Qualls JH, Stratton JJ, Harding JW, Wright JW. Norleucine1-Angiotensin IV alleviates mecamylamine-induced spatial memory deficits. Peptides. 2004;25(2):233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pederson ES, Krishnan R, Harding JW, Wright JW. A role for the angiotensin AT4 receptor subtype in overcoming scopolamine-induced spatial memory deficits. Regulatory Peptides. 2001;102(2-3):147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wright JW, Stubley L, Pederson ES, Kramár EA, Hanesworth JM, Harding JW. Contributions of the brain angiotensin IV-AT4 receptor subtype system to spatial learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(10):3952–3961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03952.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Davis CJ, Kramár EA, De A, et al. AT4 receptor activation increases intracellular calcium influx and induces a non-N-methyl-D-aspartate dependent form of long-term potentiation. Neuroscience. 2006;137(4):1369–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kramár EA, Armstrong DL, Ikeda S, Wayner MJ, Harding JW, Wright JW. The effects of angiotensin IV analogs on long-term potentiation within the CA1 region of the hippocampus in vitro. Brain Research. 2001;897(1-2):114–121. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wayner MJ, Armstrong DL, Phelix CF, Wright JW, Harding JW. Angiotensin IV enhances LTP in rat dentate gyrus in vivo. Peptides. 2001;22(9):1403–1414. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wright JW, Kramár EA, Myers EDT, Davis CJ, Harding JW. Ethanol-induced suppression of LTP can be attenuated with an angiotensin IV analog. Regulatory Peptides. 2003;113(1–3):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Benoist CC, Wright JW, Wayman GA, Harding JW. Facilitation of hippocampal synaptogenesis and spatial memory by C-terminal truncated Nle1-angiotensin IV analogues. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;339(1):35–44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.182220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tyndall SJ, Patel SJ, Walikonis RS. Hepatocyte growth factor-induced enhancement of dendritic branching is blocked by inhibitors of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and calcium/calmodulin- dependent kinases. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2007;85(11):2343–2351. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gutierrez H, Dolcet X, Tolcos M, Davies A. HGF regulates the development of cortical pyramidal dendrites. Development. 2004;131(15):3717–3726. doi: 10.1242/dev.01209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hashimoto N, Yamanaka H, Fukuoka T, Obata K, Mashimo T, Noguchi K. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor in primary sensory neurons of adult rats. Molecular Brain Research. 2001;97(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Matzke A, Sargsyan V, Holtmann B, et al. Haploinsufficiency of c-Met in cd44−/− mice identifies a collaboration of CD44 and c-Met in vivo. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2007;27(24):8797–8806. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01355-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tyndall SJ, Walikonis RS. Signaling by hepatocyte growth factor in neurons is induced by pharmacological stimulation of synaptic activity. Synapse. 2007;61(4):199–204. doi: 10.1002/syn.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dalmay F, Pesteil F, Allard J, Nisse-Durgeat S, Fernandez L, Fournier A. Angiotensin IV decreases acute stroke mortality in the gerbil. Hypertension. 2001;14(1):p. 56A. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Morishita R, Nakamura S, Hayashi SI, et al. Therapeutic angiogenesis induced by human recombinant hepatocyte growth factor in rabbit hind limb ischemia model as cytokine supplement therapy. Hypertension. 1999;33(6):1379–1384. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Van Belle E, Witzenbichler B, Chen D, et al. Potentiated angiogenic effect of scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor via induction of vascular endothelial growth factor: the case for paracrine amplification of angiogenesis. Circulation. 1998;97(4):381–390. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsuzuki N, Miyazawa T, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Shima K. Hepatocyte growth factor reduces the infarct volume after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurological Research. 2001;23(4):417–424. doi: 10.1179/016164101101198659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stragier B, Clinckers R, Meurs A, et al. Involvement of the somatostatin-2 receptor in the anti-convulsant effect of angiotensin IV against pilocarpine-induced limbic seizures in rats. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;98(4):1100–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tchekalarova J, Georgiev V. Angiotensin peptides modulatory system: how is it implicated in the control of seizure susceptibility? Life Sciences. 2005;76(9):955–970. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tchekalarova J, Georgiev V. Ang II and Ang III modulate PTZ seizure threshold in non-stressed and stressed mice: possible involvement of noradrenergic mechanism. Neuropeptides. 2006;40(5):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Grammatopoulos TN, Outeiro TF, Hyman BT, Standaert DG. Angiotensin II protects against α-synuclein toxicity and reduces protein aggregation in vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;363(3):846–851. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vaughan DE. Angiotensin and vascular fibrinolytic balance. American Journal of Hypertension. 2002;15(1, part 2):3S–8S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shang J, Deguchi K, Ohta Y, et al. Strong neurogenesis, angiogenesis, synaptogenesis, and antifibrosis of hepatocyte growth factor in rats brain after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2011;89(1):86–95. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Faure S, Chapot R, Tallet D, Javellaud J, Achard JM, Oudart N. Cerebroprotective effect of angiotensin IV in experimental ischemic stroke in the rat mediated by AT4 receptors. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2006;57(3):329–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li F, Shetty AK, Sugahara K. Neuritogenic activity of chondroitin/dermatan sulfate hybrid chains of embryonic pig brain and their mimicry from shark liver: involvement of the pleiotrophin and hepatocyte growth factor signaling pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(5):2956–2966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Moeller I, Small DH, Reed G, Harding JW, Mendelsohn FAO, Chai SY. Angiotensin IV inhibits neurite outgrowth in cultured embryonic chicken sympathetic neurones. Brain Research. 1996;725(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Korhonen L, Sjöholm U, Takei N, et al. Expression of c-Met in developing rat hippocampus: evidence for HGF as a neurotrophic factor for calbindin D-expressing neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(10):3453–3461. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Powell EM, Mühlfriedel S, Bolz J, Levitt P. Differential regulation of thalamic and cortical axonal growth by hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Developmental Neuroscience. 2003;25(2–4):197–206. doi: 10.1159/000072268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Harding JW, Cook VI, Miller-Wing AV, et al. Identification of an AII (3-8) [AIV] binding site in guinea pig hippocampus. Brain Research. 1992;583(1-2):340–343. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(10)80047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wright JW, Yamamoto BJ, Harding JW. Angiotensin receptor subtype mediated physiologies and behaviors: new discoveries and clinical targets. Progress in Neurobiology. 2008;84(2):157–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Thewke DP, Seeds NW. The expression of mRNAs for hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor, its receptor c-met, and one of its activators tissue-type plasminogen activator show a systematic relationship in the developing and adult cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Brain Research. 1999;821(2):356–367. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tyndall SJ, Walikonis RS. The receptor tyrosine kinase met and its ligand hepatocyte growth factor are clustered at excitatory synapses and can enhance clustering of synaptic proteins. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(14):1560–1568. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.14.2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stragier B, Sarre S, Vanderheyden P, et al. Metabolism of angiotensin II is required for its in vivo effect on dopamine release in the striatum of the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;90(5):1251–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lee J, Chai SY, Mendelsohn FAO, Morris MJ, Allen AM. Potentiation of cholinergic transmission in the rat hippocampus by angiotensin IV and LVV-hemorphin-7. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40(4):618–623. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Meighan SE, Meighan PC, Choudhury P, et al. Effects of extracellular matrix-degrading proteases matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 9 on spatial learning and synaptic plasticity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;96(5):1227–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Meighan PC, Meighan SE, Davis CJ, Wright JW, Harding JW. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase inhibition on short- and long-term plasticity of schaffer collateral/CA1 synapses. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;102(6):2085–2096. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Inoue T. Dynamics of calcium and its roles in the dendrite of the cerebellar Purkinje cell. Keio Journal of Medicine. 2003;52(4):244–249. doi: 10.2302/kjm.52.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Schmitz Y, Luccarelli J, Kim M, Wang M, Sulzer D. Glutamate controls growth rate and branching of dopaminergic axons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(38):11973–11981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2927-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Powell EM, Mühlfriedel S, Bolz J, Levitt P. Differential regulation of thalamic and cortical axonal growth by hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Developmental Neuroscience. 2003;25(2–4):197–206. doi: 10.1159/000072268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.McCoy AT, Benoist CC, Wright JW, et al. Evaluation of metabolically stabilized angiotensin IV analogs as pro-cognitive/anti-dementia agents. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.199497. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Allen AM, MacGregor DP, Chai SY, et al. Angiotensin II receptor binding associated with nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in human basal ganglia. Annals of Neurology. 1992;32(3):339–344. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chai SY, Mendelsohn FAO, Paxinos G. Angiotensin converting enzyme in rat brain visualized by quantitative in vitro autoradiography. Neuroscience. 1987;20(2):615–627. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chai SY, McKenzie JS, KcKinley MJ, Mendelsohn FAO. Angiotensin converting enzyme in the human basal forebrain and midbrain visualized by in vitro autoradiography. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;291(2):179–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.902910203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Strittmatter SM, Thiele EA, Kapiloff MS, Snyder SH. A rat brain isozyme of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260(17):9825–9832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Reardon KA, Mendelsohn FAO, Chai SY, Horne MK. The angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, perindopril, modifies the clinical features of Parkinson’s disease. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine. 2000;30(1):48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2000.tb01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jenkins TA, Mendelsohn FAO, Chai SY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme modulates dopamine turnover in the striatum. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;68(3):1304–1311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68031304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ehlers MRW, Riordan JF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme: new concepts concerning its biological role. Biochemistry. 1989;28(13):5311–5318. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chabrashvili T, Kitiyakara C, Blau J, et al. Effects of ANG II type 1 and 2 receptors on oxidative stress, renal NADPH oxidase, and SOD expression. American Journal of Physiology. 2003;285(1):R117–R124. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00476.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rodriguez-Pallares J, Rey P, Parga JA, Muñoz A, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Brain angiotensin enhances dopaminergic cell death via microglial activation and NADPH-derived ROS. Neurobiology of Disease. 2008;31(1):58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Jenkins TA, Wong JYF, Howells DW, Mendelsohn FAO, Chai SY. Effect of chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on striatal dopamine content in the MPTP-treated mouse. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73(1):214–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Muñoz A, Rey P, Guerra MJ, Mendez-Alvarez E, Soto-Otero R, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Reduction of dopaminergic degeneration and oxidative stress by inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme in a MPTP model of parkinsonism. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51(1):112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lopez-Real A, Rey P, Soto-Otero R, Mendez-Alvarez E, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition reduces oxidative stress and protects dopaminergic neurons in a 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of Parkinsonism. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2005;81(6):865–873. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mertens B, Vanderheyden P, Michotte Y, Sarre S. The role of the central renin-angiotensin system in Parkinson's disease. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2010;11(1):49–56. doi: 10.1177/1470320309347789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Babior BM. NADPH oxidase. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2004;16(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Joglar B, Rodriguez-Pallares J, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Rey P, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. The inflammatory response in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease is mediated by brain angiotensin: relevance to progression of the disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;109(2):656–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Okamura A, Rakugi H, Ohishi M, et al. Upregulation of renin-angiotensin system during differentiation of monocytes to macrophages. Journal of Hypertension. 1999;17(4):537–545. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mertens B, Varcin M, Michotte Y, Sarre S. The neuroprotective action of candesartan is related to interference with the early stages of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced dopaminergic cell death. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;34(7):1141–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rodriguez-Perez AI, Valenzuela R, Joglar B, Garrido-Gil P, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Renin angiotensin system and gender differences in dopaminergic degeneration. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2011;6(1):58–70. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rodriguez-Perez AI, Valenzuela R, Villar-Cheda B, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Dopaminergic neuroprotection of hormonal replacement therapy in young and aged menopausal rats: role of the brain angiotensin system. Brain. 2012;135(1):124–138. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Grammatopoulos TN, Jones SM, Ahmadi FA, et al. Angiotensin type I receptor antagonist losartan, reduces MPTP-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2007;2(1, article 1):17 pages. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Garrido-Gil P, Joglar B, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Involvement of PPAR-gamma in the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin type 1 receptor inhibition: effects of the receptor antagonist telmisartan and receptor deletion in a mouse MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2012;9(1, article 38):16 pages. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Becker C, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of antihypertensives and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70(16):1438–1444. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303818.38960.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ascherio A, Tanner CM. Use of antihypertensives and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;72(6):578–579. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344171.22760.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Sarma GRK, Kamath V, Matthew T, Roy AK. A case of Parkinsonism worsened by losartan: a probable new adverse effect. Movement Disorders. 2008;23(7):p. 1055. doi: 10.1002/mds.21945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Grady EF, Sechi LA, Griffin CA, Schambelan M, Kalinyak JE. Expression of AT2 receptors in the developing rat fetus. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88(3):921–933. doi: 10.1172/JCI115395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Lenkei Z, Palkovits M, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. Distribution of angiotensin II type-2 receptor (AT2) mRNA expression in the adult rat brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;373(3):322–339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960923)373:3<322::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]