Abstract

Aims: The activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/serine/threonine protein kinase (Akt) is enhanced under hypertension. The phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is a negative regulator of PI3K signaling, and its activity is redox-sensitive. In the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), which is responsible for the maintenance of blood pressure, oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in neurogenic hypertension. The present study evaluated the hypothesis that redox-sensitive inactivation of PTEN results in enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM, leading to neurogenic hypertension. Results: Compared to age-matched normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats, PTEN inactivation in the form of oxidation and phosphorylation were greater in RVLM of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). PTEN inactivation was accompanied by augmented PI3K activity and PI3K/Akt signaling, as reflected by the increase in phosphorylation of Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin. Intracisternal infusion of tempol or microinjection into the bilateral RVLM of adenovirus encoding superoxide dismutase significantly antagonized the PTEN inactivation and blunted the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in SHR. Gene transfer of PTEN to RVLM in SHR also abrogated the enhanced Akt activation and promoted antihypertension. Silencing PTEN expression in RVLM with small-interfering RNA, on the other hand, augmented PI3K/Akt signaling and promoted long-term pressor response in normotensive WKY rats. Innovation: The present study demonstrated for the first time that the redox-sensitive check-and-balance process between PTEN and PI3K/Akt signaling is engaged in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Conclusion: We conclude that an aberrant interplay between the redox-sensitive PTEN and PI3k/Akt signaling in RVLM underpins neural mechanism of hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 36–50.

Introduction

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/serine/threonine protein kinase (Akt) signaling is involved in the regulation of a wide variety of cellular activities in many tissues. In the cardiovascular system, emerging evidence supports the involvement of PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling pathways in normal cellular functions that include maturation and growth (29, 50), mechanotransduction (56), contractility (29, 39), or proliferation and migration (14) of cardiac or vascular smooth muscle cells. Dysfunction of this signaling pathway therefore plays a pivotal role in cardiovascular pathophysiology, including myocardial infarction (13), heart failure (46), atherosclerosis (41), and hypertension (42).

PI3K catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (PI)-4,5-diphosphate to PI-3,4,5-triphosphate, which activates Akt via phosphorylation at the serine residues (51). By removing 3-phosphate from the inositol moieties and proteins phosphorylated by PI3K, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), first identified as a tumor suppressor gene (34), is one of the major regulators of PI3K signaling (33). As an intrinsic PI3K inhibitor (37), overexpression of PTEN reduces PI3K/Akt signaling, resulting in reduced proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (16); repression of PTEN increases Akt-driven proliferation of smooth muscle cells (40). Whereas the regulatory mechanisms of PTEN on PI3K/Akt pathways have been characterized in great detail, the mechanisms that underlie modulation of PTEN activity, which in turn alters PI3K/Akt signaling under disease conditions, require further elucidation.

Innovation.

The present study provides two novel mechanistic insights on oxidative stress-associated neurogenic hypertension. First, we demonstrated that redox-sensitive inactivation of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) through oxidation and phosphorylation, which leads to overactivation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/serine/threonine protein kinase (Akt) signaling in rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), underpins the manifestation of hypertension phenotype. Second, this is the first time that the check-and-balance process between PTEN and PI3K/Akt signaling, which is well-documented in tumorogenesis, is also engaged in the pathogenesis of hypertension, and in a redox-sensitive manner. The antihypertensive effect observed after overexpression of PTEN in RVLM further supports the innovative notion that PTEN may be a novel therapeutic target for oxidative stress-associated hypertension.

PTEN activity is regulated by both phosphorylation and oxidation. Phosphorylation suppresses PTEN activity by increasing its stability (57), thus preventing its recruitment to the plasma membrane and decreasing its catalytic activity (12). PTEN activity can additionally be inactivated through oxidation of its cysteine residue (28). Recent studies demonstrated that both regulatory mechanisms on PTEN activity are affected by the redox state. The elevated tissue level of the reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly superoxide anion (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), inactivate PTEN directly via oxidation or indirectly via phosphorylation, resulting in activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade (22). Treatment with a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic, tempol, on the other hand, markedly reduces diabetes-enhanced phosphorylation of PTEN in the endothelium of mouse aorta (55).

In the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), where sympathetic premotor neurons for the maintenance of peripheral vasomotor tone are located (48), oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in neural mechanism of hypertension (4, 24, 38). At the same time, a functional role for PI3K signaling at RVLM in the manifestation of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) has been implicated (58). The mRNA level of specific class I PI3K subunits is significantly elevated in RVLM, and PI3K activity is increased in brain stem neuronal cultures derived from SHR (58). Acute PI3K inhibition within RVLM, on the other hand, decreases blood pressure in SHR to levels that are similar to those in normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats (53).

The impact of redox-sensitive aberrant modulation of PTEN activity in RVLM on the manifestation of PI3K/Akt-associated hypertension remains unclear. We tested in the present study the hypothesis that enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR is attributable to redox-sensitive inactivation of PTEN via phosphorylation and oxidation of the phosphatase.

Results

Increased oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN and enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR

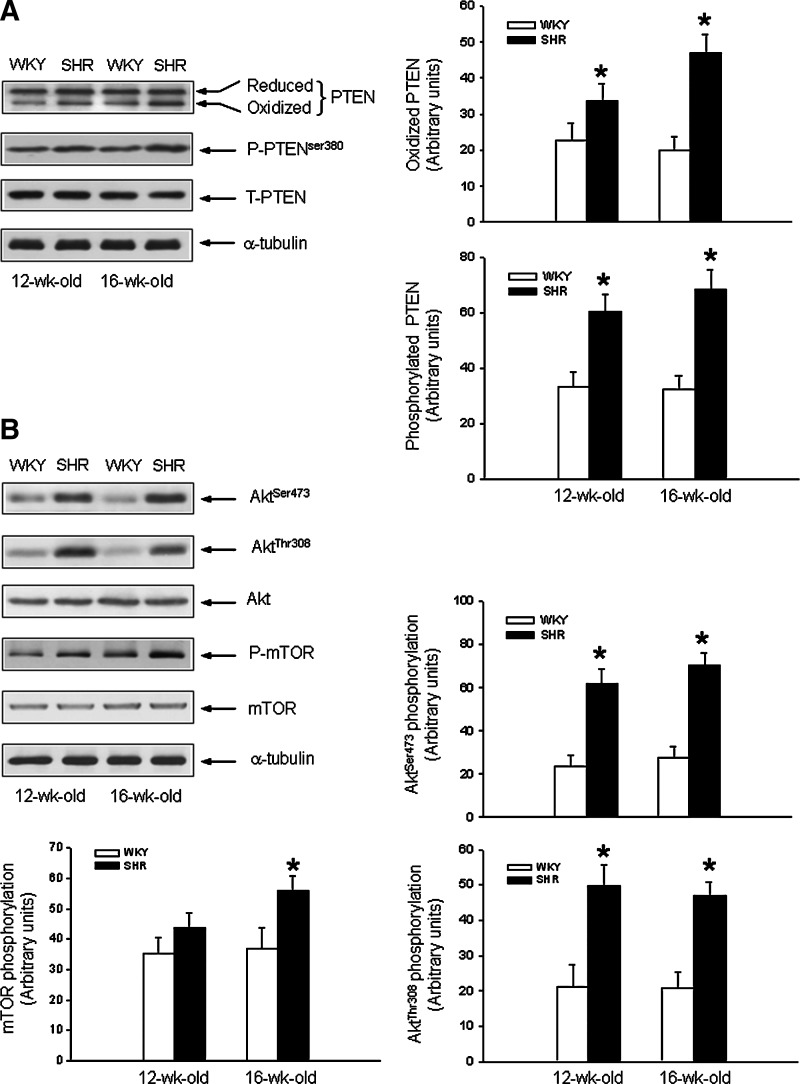

Compared to age-matched WKY rats, oxidation or phosphorylation of PTEN (Fig. 1A) was significantly greater in RVLM of SHR with established hypertension (12-week-old: 165±4 mmHg vs. 109±3 mmHg, n=8; 16-week-old: 183±5 mmHg vs. 116±4 mmHg, n=8). There was also a parallel reduction in PTEN phosphatase activity (12-week-old: −32.4%±3.4%, p<0.05; n=8; 16-week-old: −37.6%±4.2%, p<0.05; n=8). The augmented oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN were accompanied by an elevation of PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR, as reflected by the increases in phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream protein, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (45, 52) (Fig. 1B). The expression of total PTEN (Fig. 1A), Akt, or mTOR (Fig. 1B) in RVLM, however, was not significantly different between SHR and WKY rats. There was also no significant difference between SHR and WKY rats in the expression of total PTEN, phosphorylated or oxidized PTEN in brain stem sites adjacent to RVLM (e.g., ventromedial medulla) (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). In addition, PTEN immunoreactivity was presented only in RVLM neurons of SHR (Supplementary Fig. S2), but not in astrocytes or microglia.

FIG. 1.

Increased oxidation and phosphorylation of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) and enhanced phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/serine/threonine protein kinase (Akt) activity in rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR). (A) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of reduced or oxidized PTEN, or phosphorylated PTEN (P-PTEN) or total PTEN (T-PTEN), detected from RVLM of normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats or SHR at age of 12 or 16 weeks. Tissue samples from RVLM were collected by micropunches, and the extracted protein was analyzed using Western blotting as described under the Materials and Methods section. (B) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of phosphorylated Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (P-mTOR), total Akt or mTOR, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of normotensive WKY rats or SHR at age of 12 or 16 weeks. Values are mean±standard error of mean of four independent experiments on samples pooled from six to eight animals in each group. *p<0.05 versus age-matched WKY rat group in the Student's t-test.

Persistence of PTEN inactivation in RVLM after peripheral antihypertensive treatment in SHR

To confirm that the reduction in PTEN activity at RVLM of SHR is not secondary to hypertension, SHR (16-week-old) with established hypertension (176.5±3.4 mmHg, n=6) was orally ingested with amlodipine (5 mg/kg/day), a calcium channel blocker that induces hypotension mainly via peripheral vasodilation (20) for 7 days. On day 7, when mean systemic arterial pressure (MSAP) in SHR was significantly lowered (126±4.6 mmHg, n=6), the augmented oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN in RVLM (Supplementary Fig. S3), alongside a reduction in phosphatase activity (−34.2%±3.9%, n=6) remained unaltered.

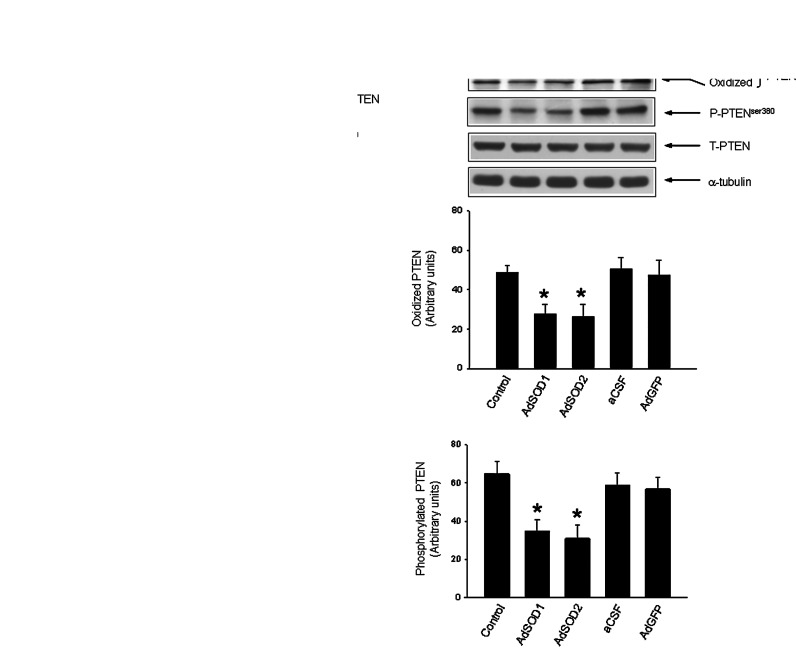

Oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN in RVLM of SHR are mediated by NADPH oxidase- and mitochondria-derived ROS

The increased ROS production in RVLM of SHR can take origin from NADPH oxidase (3) and mitochondria (7). To evaluate the potential involvement of these two sources of ROS in the increased oxidation or phosphorylation of PTEN in RVLM, SHR were subject to intracisternal infusion of an antisense oligonucleotide (ASON) or sense oligonucleotide (SON) against p47phox (100 pmol/h/μl) or coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10; 1 nmol/h/μl) for 7 days. Those two treatment schemes have been reported to decrease ROS generation by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activity (3, 6) or preserving mitochondrial electron transport chain capacity (7) in RVLM. Measured on day 7 after p47phox ASON or CoQ10 treatment, the augmented oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN in RVLM of SHR were significantly decreased (Fig. 2A). The same treatments, however, did not significantly affect total PTEN expression. The specificity of p47phox ASON was confirmed by observations that the treatment did not affect Nox4 in RVLM (Supplementary Fig. S4), the expression and activation of which do not require p47phox subunit (54). We reported previously (27) that 7 days after transfection of the adenoviral vector encoding SOD1 or SOD2 (AdSOD1 or AdSOD2) into RVLM, the expression of cytosol SOD1 or mitochondrial SOD2 is upregulated, alongside reduced cytosolic and mitochondrial O2•− level. Microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdSOD1 (5×108 pfu) or AdSOD2 (5×108 pfu) in the present study also retarded the augmented oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN (Fig. 2B), alongside significant reversal of the reduced PTEN activity (the adenoviral vector encoding the green fluorescent protein [AdGFP] vs. AdSOD1 or AdSOD2: −34.4%±3.1% vs. −19.2%±3.4% or −23.6%±2.6%, p<0.05; n=6) in RVLM of SHR, detected on day 7 after transfection.

FIG. 2.

Oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN in RVLM of SHR are mediated by NADPH oxidase- and mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS). (A) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of reduced or oxidized PTEN, P-PTEN or T-PTEN, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of SHR (at age of 16 weeks) on day 7 after intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), antisense oligonucleotide (ASON) or sense oligonucleotide (SON) against p47phox subunit of the NADPH oxidase, a mobile electron carrier in the inner membrane of mitochondria, coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10). Infusion of test agents into the cisterna magna was performed as described under the Materials and Methods section. (B) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of reduced or oxidized PTEN, P-PTEN or T-PTEN, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of SHR (at age of 16 weeks) on day 7 after microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of adenovirus encoding superoxide dismutase 1 or 2 (AdSOD1 or AdSOD2), or adenoviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein (AdGFP). In vivo gene delivery of AdSOD1 or AdSOD2 to the bilateral RVLM was performed as described under the Materials and Methods section. Values are mean±standard error of mean of four independent experiments on samples pooled from six to eight animals in each group. *p<0.05 versus sham-control group in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis.

Increase in tissue level of ROS in RVLM induces oxidation/phosphorylation of PTEN and activation of PI3K/Akt signaling in WKY rats

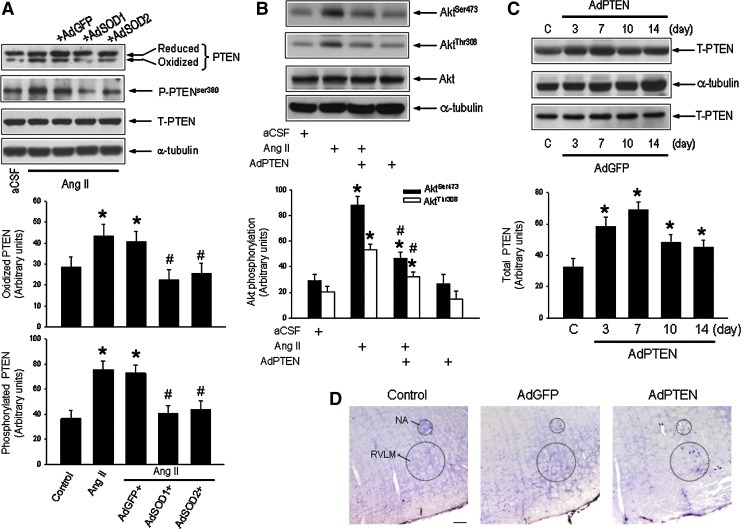

To further confirm a permissive role for ROS in the inactivation of PTEN that leads to activation of PI3K/Akt signaling, angiotensin II (Ang II) (100 ng/h/μl) was infused into the cisterna magna to increase ROS production in RVLM (6) of WKY rats. On day 7 following Ang II infusion, oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN (Fig. 3A) in RVLM were significantly increased in those normotensive rats. The phosphatase activity of PTEN was also significantly reduced (−21.8%±3.2%, p<0.05; n=8). This elevated oxidation or phosphorylation of PTEN was blunted in animals that were pretreated with microinjected bilaterally into RVLM of AdSOD1 (5×108 pfu) or AdSOD2 (5×108 pfu), immediately before Ang II infusion (Fig. 3A). Intracisternal infusion of Ang II (100 ng/h/μl) also augmented PI3K/Akt signaling, as demonstrated by the increase in phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 in RVLM (Fig. 3B). This induced phosphorylation of Akt by Ang II was inhibited on microinjection into the bilateral RVLM of adenoviral vector encoding PTEN (AdPTEN) (5×108 pfu) (Fig. 3B), which significantly increased protein expression of PTEN (Fig. 3C) and the intensity of PTEN-immunoreactivity in RVLM cells (Fig. 3D) that peaked at day 7 after transfection. AdPTEN treatment, on the other hand, elicited no apparent effect on the enzyme activity of NADPH oxidase, the tissue level of O2•− or the total SOD activity in RVLM of WKY rats (Supplementary Fig. S5). In acute experiments, on day 7 after intracisternal infusion of Ang II, microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (10 pmol) or wortmannin (100 nmol) antagonized phosphorylation of Ser473 and Thr308 residues of Akt, detected 120 min postinjection (Supplementary Fig. S6).

FIG. 3.

Increased tissue level of ROS in RVLM induces oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN and activation of PI3K in normotensive WKY rats. (A) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of reduced or oxidized PTEN, P-PTEN or T-PTEN, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of WKY rats (at age of 16 weeks) on day 7 after i.c. infusion of aCSF or angiotensin II (Ang II), alone or with additional microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdSOD1, AdSOD2. (B) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of phosphorylated Akt or total Akt, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of WKY rats (at age of 16 weeks) on day 7 after i.c. infusion of aCSF or Ang II, alone or with additional microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of adenoviral vector encoding PTEN (AdPTEN). In vivo gene delivery of AdSOD1, AdSOD2 or AdPTEN to the RVLM was performed immediately after implantation of osmotic minipumps for i.c. infusion of Ang II as described under the Materials and Methods section. Also shown are representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of temporal changes in protein level of T-PTEN (C) in RVLM of WKY rats after microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdPTEN (top panel) or AdGFP (bottom panel). (D) Representative photomicrographs showing PTEN-immunoreactive cells in RVLM of WKY rats subjected to microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdGFP or AdPTEN. Values are mean±standard error of mean of four independent experiments on samples pooled from five to eight animals in each group. *p<0.05 versus aCSF or sham-control (C) group, and #p<0.05 versus Ang II group in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis. Dotted circle in (D) depicts anatomical confines of nucleus ambiguous (NA) or RVLM. Scale bar: 100 μm. (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.)

Suppression of PTEN increases PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of WKY rats

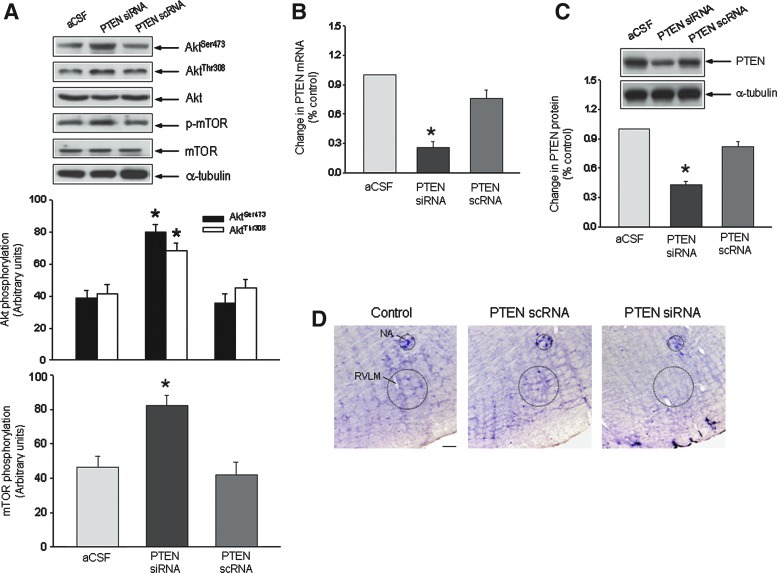

To examine whether a reduction in PTEN activity in RVLM effectively increases PI3K/Akt signaling under normotensive condition, the expression of PTEN was inhibited by gene knockdown. Microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of PTEN small-interfering RNA (siRNA; 1 nmol) resulted in an increase in PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of WKY rats, as reflected by an increase in phosphorylation of Akt or mTOR (Fig. 4A). The same treatment also significantly decreased the phosphatase activity of PTEN (−48.2%±6.5%, p<0.05; n=6). The effectiveness of PTEN siRNA treatment was confirmed by a reduction in PTEN mRNA (Fig. 4B) and protein (Fig. 4C) expression, or a decrease in the number of PTEN-immunoreactive cells in RVLM (Fig. 4D). Again, PTEN siRNA treatment elicited minimal effect on the NADPH oxidase activity, the tissue level of O2•− or the total SOD activity in RVLM of WKY rats (Supplementary Fig. S5).

FIG. 4.

Suppression of PTEN increases PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of normotensive WKY rats. (A) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of phosphorylated Akt or mTOR, total Akt or mTOR, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of WKY rats (at age of 16 weeks) 48 h after microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of PTEN small-interfering RNA (siRNA) or scrambled siRNA (scRNA). Microinjection into the bilateral RVLM of siRNA or scRNA was carried out as described under the Materials and Methods section. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of PTEN mRNA (B), or densitometric analysis of protein level of PTEN (C) from RVLM of WKY rats (at age of 16 weeks), detected 48 h after microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of PTEN siRNA or scRNA. Tissue samples were collected from RVLM and mRNA or protein level was determined using real time PCR or Western blotting. (D) Representative photomicrographs showing PTEN-immunoreactive cells in RVLM of SHR subjected to microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of PTEN scRNA or siRNA. Values are mean±standard error of mean of four independent experiments on samples pooled from six to eight animals in each group. *p<0.05 versus aCSF group in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis. Dotted circle in (D) depicts anatomical confine of NA or RVLM. Scale bar: 100 μm. (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.)

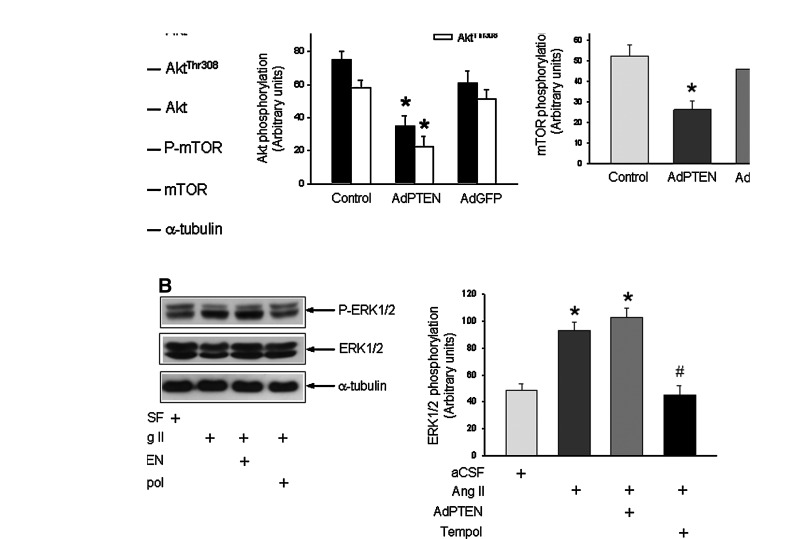

Overexpression of PTEN reverses the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR

We next evaluated whether overexpression of PTEN in RVLM affects the augmented PI3K/Akt signaling in SHR. Compared to AdGFP transfection, microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdPTEN (5×108 pfu) significantly blunted the augmented PI3K/Akt signaling, as indicated by a reduction in phosphorylation of Akt or mTOR, determined on day 7 after AdPTEN transfection (Fig. 5A). Overexpression of PTEN transgene in RVLM also resulted in a significant increase in PTEN enzyme activity in RVLM of SHR (+31.5%±4.5%, p<0.05, n=6) and WKY rats (+27.9%±3.8%, p<0.05; n=6). Application of AdPTEN to areas outside the confines of RVLM (e.g., ventromedial medella) elicited minimal effect on the augmented PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR (Supplementary Fig. S7). AdPTEN treatment also did not affect the augmented enzyme activity of NADPH oxidase, the heightened tissue level of O2•− or the reduced activity of SOD in RVLM of SHR (Supplementary Fig. S5).

FIG. 5.

Overexpression of PTEN blunted the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR. (A) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of phosphorylated Akt or mTOR, total Akt or mTOR, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of SHR (at age of 16 weeks) on day 7 after microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdPTEN or AdGFP. Tissue samples were collected from RVLM and protein expression was determined using Western blotting as described under the Materials and Methods section. (B) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of protein level of total and phosphorylated ERK1/2, or α-tubulin, detected from RVLM of WKY rats (at age of 16 weeks) on day 7 after i.c. infusion of Ang II, alone or with additional microinjection into bilateral RVLM of AdPTEN or coinfusion of tempol into the cisterna magna. Note that in vivo gene delivery of AdPTEN to the RVLM significantly reversed the Ang II-induced phosphorylation of Akt or mTOR, but not the induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Values are mean±standard error of mean of four independent experiments on samples pooled from six to seven animals in each group. *p<0.05 versus aCSF or sham-control group, and #p<0.05 versus Ang II group in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis.

Downregulation of PTEN averts the antioxidant-induced reversal of the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR

To further confirm that ROS activates the PI3K/Akt pathway through PTEN inactivation in RVLM, PI3K/Akt signaling was examined in SHR treated with coinfusion into the cisterna magna of p47phox ASON (100 pmol/h/μl) and CoQ10, (1 nmol/h/μl), alone or with additional PTEN siRNA (1 nmol). On day 7, after intracisternal coinfusion of p47phox ASON and CoQ10, the augmentation in the tissue level of O2•− in RVLM of SHR (Supplementary Fig. S8A) was significantly blunted; and the enhanced phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 was significantly lessened (Supplementary Fig. S8B). This antioxidant-associated reversal of the augmented PI3K/Akt signaling was partially blocked by microinjection bilaterally into the RVLM of PTEN siRNA on day 5 after intracisternal coinfusion of the antioxidants. On the other hand, PTEN siRNA treatment alone was ineffective against the augmented NADPH oxidase activity, the tissue level of O2•− or the reduced SOD activity in RVLM of SHR (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Overexpression of PTEN in RVLM does not affect Ang II-induced activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 in WKY rats

We next employed Ang II-induced activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) in RVLM to ascertain that redox-sensitive modulation of PTEN is specific to PI3K/Akt signaling. As in our previous experiments (3), intracisternal infusion of Ang II (100 ng/h/μl) for 7 days also induced an increase in phosphorylation of ERK1/2, particularly the 42 KDa fragment of the kinase in RVLM (Fig. 5B). The Ang II-induced ERK phosphorylation was significantly reduced by coinfusion into the cisterna magna of tempol (1 μmol//h/μl), but not by overexpression of PTEN (5×108 pfu) in RVLM with AdPTEN gene transfection.

Overexpression or downregulation of PTEN has no effect on PI3K activity in RVLM

PI3K enzyme activity in RVLM was measured to confirm that alteration in PI3K/Akt signaling in response to PTEN manipulation was not the result of change in PI3K activity per se. Compared to WKY rats, PI3K activity in RVLM was significantly higher in SHR (Supplementary Fig. S9). This augmented PI3K activity was, however, not affected by treatments with AdPTEN (5×108 pfu) or PTEN siRNA (1 nmol) in the bilateral RVLM.

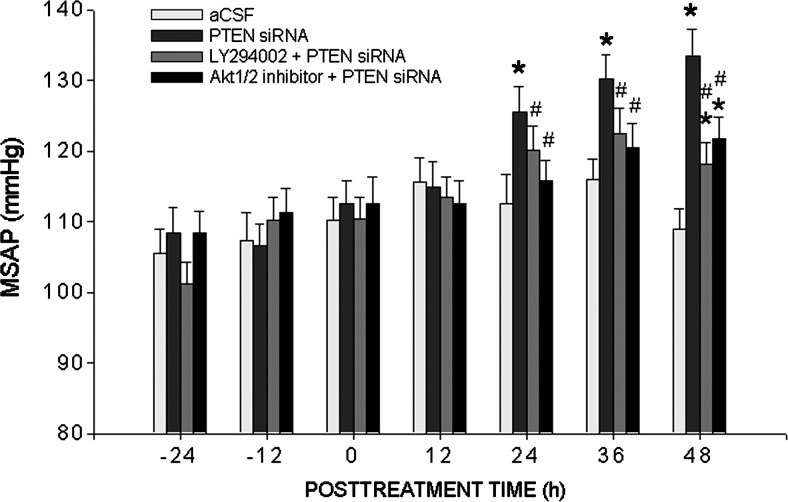

Silencing PTEN in RVLM promotes pressor responses in WKY rats

To establish a causal role for PTEN in RVLM in PI3K/Akt-associated neurogenic hypertension, PTEN siRNA (1 nmol) was microinjected bilaterally into RVLM of WKY rats. This treatment resulted in a progressive increase in MSAP that amounted to 18.2%±3.5% (n=6) at the end of 48 h postinjection (Fig. 6), with no significant change in heart rate (HR) (data not shown). This induced pressor response was significantly attenuated by LY294002 (10 pmol/h/μl) or Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor (50 pmol/h/μl), infused into the cisterna magna immediately after PTEN siRNA treatment. Microinjection of PTEN scrambled siRNA (scRNA) into RVLM, or infusion of LY294002 or Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor into the cisterna magna did not alter MSAP of WKY rats (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Silencing PTEN in RVLM promotes pressor responses in normotensive WKY rats. Temporal changes in mean systemic arterial pressure (MSAP) in WKY rats that received microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of PTEN siRNA, alone or with additional i.c. infusion of PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, or Akt kinase inhibitor. SAP was recorded for 48 h under conscious conditions by radiotelemetry. Values are mean±standard error of mean recorded from six to eight animals per group. *p<0.05 versus aCSF group and #p<0.05 versus PTEN siRNA group at corresponding time points in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis.

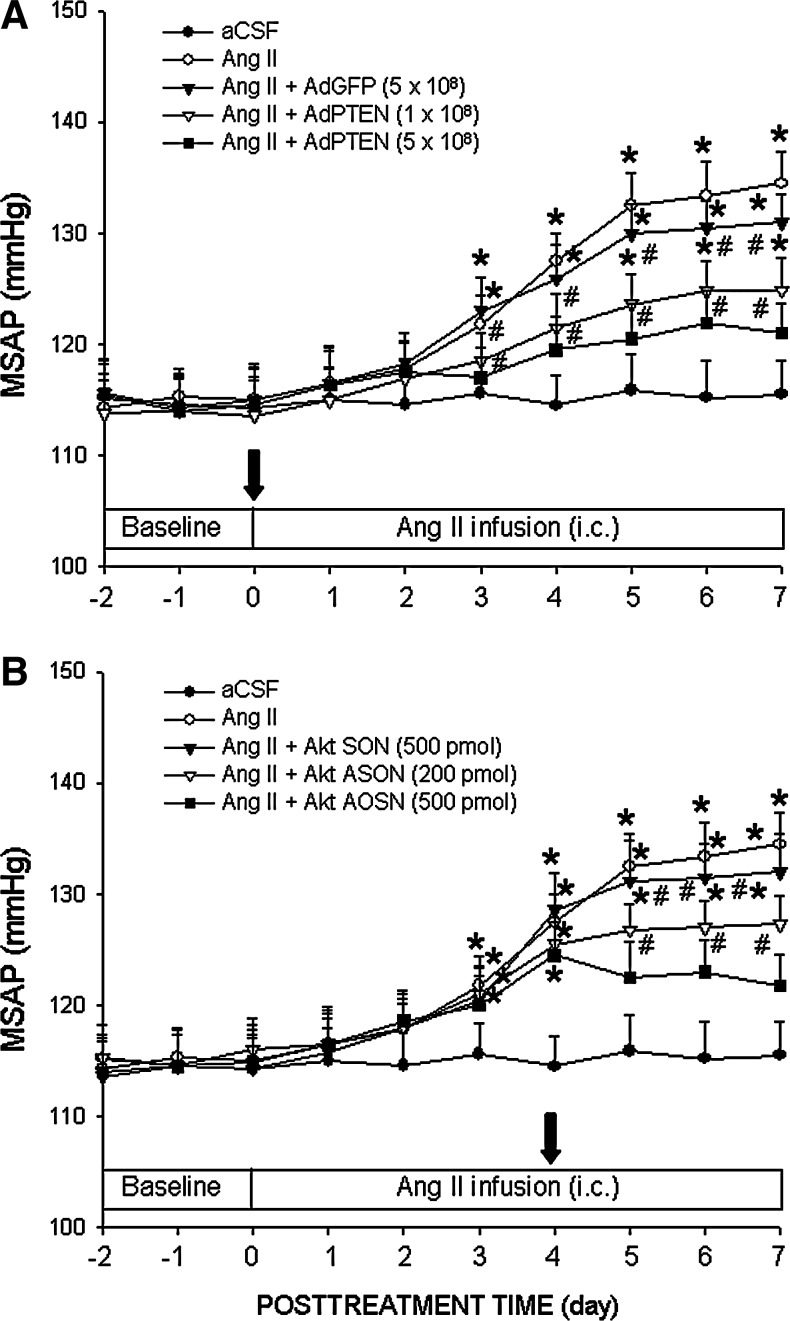

Overexpression of PTEN or gene knockdown of Akt in RVLM attenuates Ang II-induced long-term pressor response in WKY rats

We next determine whether PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM plays an active role in the manifestation of neurogenic hypertension, and the significance of redox-sensitive inactivation of PTEN activity in PI3K/Akt-drivien cardiovascular phenotype. For this purpose, AdPTEN (1 or 5×108 pfu) was microinjected bilaterally into RVLM immediately before infusion of Ang II (100 ng/h/μl) into the cisterna magna, or Akt ASON (200 or 500 pmol) was microinjected to the bilateral RVLM on day 4 after Ang II infusion. Compared to AdGFP (Fig. 7A) or Akt SON (Fig. 7B), AdPTEN or Akt ASON treatment blunted significantly the Ang II-induced long-term pressor response in a dose-related manner. The effectiveness of Akt ASON was confirmed by a significant reduction in Akt protein expression and Ang II-induced activation of Akt activity in RVLM, as reflected by a reduction in phosphorylation of mTOR (Supplementary Fig. S10).

FIG. 7.

Overexpression of PTEN or gene knockdown of Akt in RVLM attenuates Ang II-induced long-term pressor response in normotensive WKY rats. Temporal changes in MSAP of WKY rats that received i.c. infusion of Ang II, alone or with additional microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdPTEN or AdGFP (A) or Akt ASON or SON (B). AdPTEN or AdGFP was microinjected into the bilateral RVLM immediately following implantation of osmotic minipumps for i.c. infusion of Ang II as described under the Materials and Methods section. Akt ASON or SON was microinjected into the bilateral RVLM on day 4 after i.c. infusion of Ang II. SAP was recorded in animals under conscious condition by radiotelemetry. Values are mean±standard error of mean recorded from five to nine animals per group. *p<0.05 versus aCSF group and #p<0.05 versus Ang II group at corresponding time points in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis.

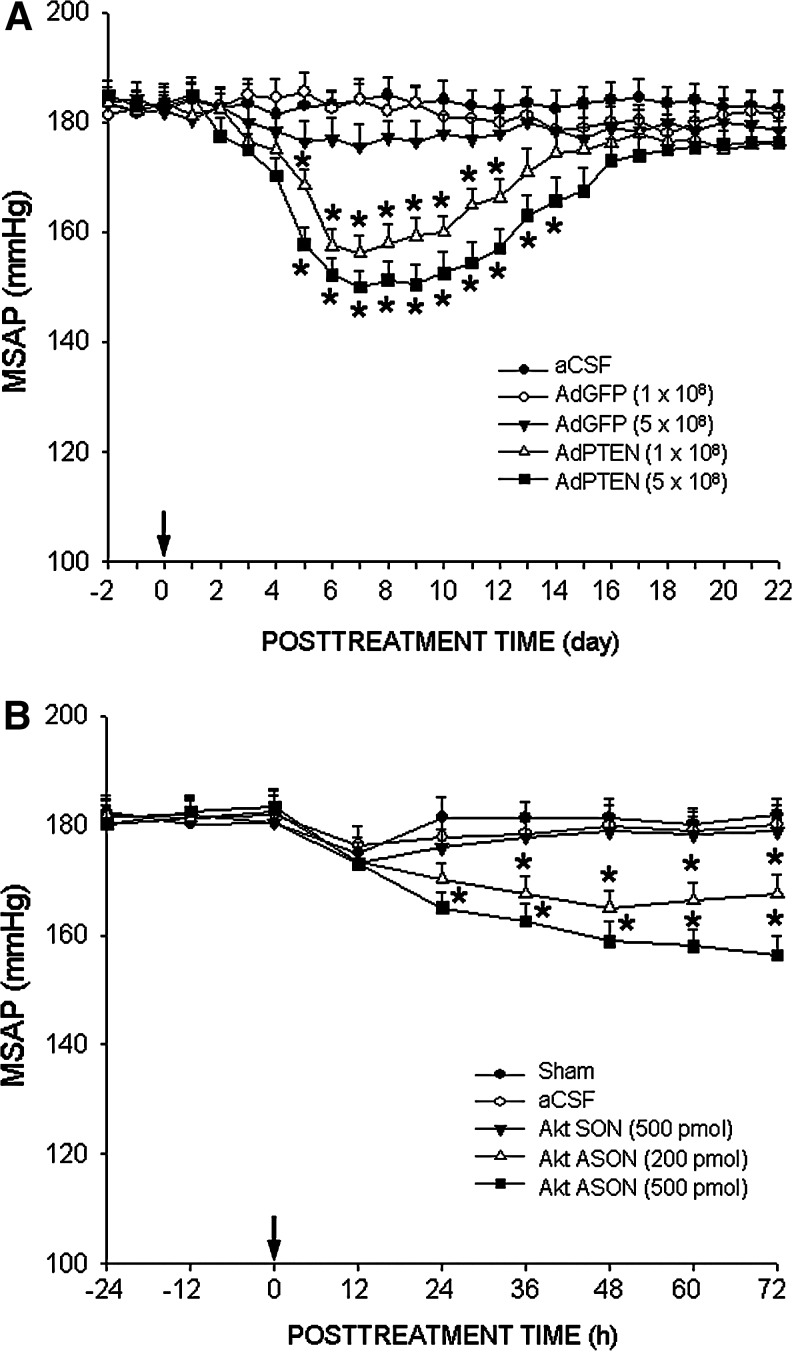

Overexpression of PTEN or gene knockdown of Akt in RVLM promotes antihypertension in SHR

We next establish that the augmented PI3K/Akt signaling resultant from redox-sensitive inactivation of PTEN is also causally related to hypertension phenotype in SHR. Compared to AdGFP transfection or Akt SON treatment, microinjection bilaterally into RVLM of AdPTEN (1 or 5×108 pfu) (Fig. 8A) or Akt ASON (200 or 500 pmol) (Fig. 8B) resulted in sustained antihypertension in SHR that endured at least 14 days or 72 h respectively, without affecting HR (data not shown). The maximal decrease of MSAP induced by overexpression of PTEN in RVLM of SHR amounted to 16.8%±3.7% (n=6).

FIG. 8.

Overexpression of PTEN or gene knockdown of Akt in RVLM promotes antihypertension in SHR. Temporal changes in MSAP of SHR following microinjection into the bilateral RVLM of AdPTEN or AdGFP (A), or Akt ASON or SON (B). AdPTEN, AdGFP, Akt ASON or Akt SON was microinjected into the bilateral RVLM on day 0, and SAP was recorded in animals under conscious condition by radiotelemetry. Changes in MSAP of SHR after overexpression of PTEN in RVLM were recorded for 22 days; and those after Akt ASON treatment was recorded for 72 h. Values are mean±standard error of mean recorded from five to eight animals per group. *p<0.05 versus aCSF group at corresponding time points in the post hoc Scheffé multiple range analysis.

Gene knockdown of PTEN in RVLM antagonizes p47phox ASON-promoted antihypertension in SHR

Finally, to confirm a contributing role of PTEN inactivation in oxidative stress-associated neurogenic hypertension in SHR, the effect of gene knockdown by PTEN siRNA on antihypertension promoted by gene knockdown of p47phox was investigated. Microinjection bilaterally into the RVLM of p47phox ASON (250 pmol) resulted in a significant decrease in MSAP in SHR, but not WKY rats, which lasted at least 48 h (Supplementary Fig. S11). This induced antihypertension by p47phox ASON was significantly antagonized by comicroinjection of PTEN siRNA (1 nmol) into the bilateral RVLM.

Microinjection sites in RVLM

Confocal microscopy showed that examined on day 7 following microinjection of AdGFP or GFP-tagged siRNA into RVLM, the expression of green fluorescence was distributed within the confines of this medullary site (Supplementary Fig. S12A–C). Light microscopy also demonstrated that the tip of the micropipettes used for injection of various test agents was located in RVLM (Supplementary Fig. S12D).

Discussion

The present study provided novel findings to reveal that depression of PTEN activity induced by NADPH oxidase- and mitochondria-derived oxidative stress through both oxidation and phosphorylation of the phosphatase results in enhanced activation of PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM that leads to neurogenic hypertension in SHR. We also found that overexpression of PTEN transgene in RVLM increased PTEN protein expression and enzyme activity, blunted the elevated PI3K/Akt signaling and conferred protection against oxidative stress-associated hypertension in SHR or Ang II-induced pressor response in WKY rats. These results together demonstrated for the first time a pivotal role for PTEN in brain stem cardiovascular regulation. In particular, an aberrant interplay between the redox-sensitive PTEN and PI3k/Akt signaling in RVLM may underpin the pathophysiology of oxidative stress-associated neurogenic hypertension.

We found in the present study that ROS may reduce PTEN activity in RVLM of SHR through both increasing its stability via phosphorylation and decreasing its catalytic activity by oxidation. Oxidative stress, on the other hand, exerted no notable influence on protein expression of the phosphatase. PTEN function is regulated by its interaction with the cell membrane, which is determined largely by the degree of phosphorylation of its C-terminal tail (57). Phosphorylated PTEN must be dephosphorylated before it can bind to membrane PDZ-containing proteins to assume full functionality as a lipid phosphatase (12). An elevation in phosphorylation of PTEN by ROS thus increases its protein stability and retains this phosphatase in an inactive state (12). Similar to other members of the protein tyrosine phosphatase family, PTEN also possesses a highly reactive cysteine residue within its active site that participates directly in catalysis and must be in the reduced state for its activity (35, 44). Maintenance of PTEN in an oxidized state by the elevated tissue level of ROS may thus reduce the catalytic activity of this phosphatase. In this regard, O2•−-dependent oxidation of PTEN was reported to result from S-nitrosylation of the phosphatase (32). Furthermore, H2O2 induces PTEN inactivation via the formation of a disulfide bond in the active site of PTEN (44). Whether oxidation of PTEN makes the phosphatase more prone to be phosphorylated by exposing critical phosphorylation sites is not clear. As such, potential cross talk between redox-sensitive oxidation and phosphorylation of PTEN in determination of PTEN activity under hypertension awaits further investigation. Based on gene transfer of AdSOD1 or AdSOD2 to overexpress cytosolic SOD1 or mitochondrial SOD2 transgene and to normalize O2•− and H2O2 levels in RVLM (27), we showed that both cytosolic and mitochondrial oxidative stress are involved in the observed inactivation of PTEN in SHR. Experimental manipulations using CoQ10 or p47phox ASON extended these findings to demonstrate that NADPH oxidase and mitochondrial electron transport chain are the major cellular sources of ROS that induces phosphorylation and oxidation of PTEN in RVLM of SHR. Previous studies (18, 60) reported that PTEN inactivation may in turn induce oxidative stress. By showing that overexpression by AdPTEN or downregulation by siRNA of PTEN in RVLM of SHR and WKY rats exerted insignificant alterations in tissue level of O2•− or enzyme activity of NADPH oxidase or total SOD, our results deemed the presence of a reciprocal negative interaction between O2•− and PTEN in RVLM unlikely. We also reason that our observed PTEN inactivation in SHR is not because of age because the degree of oxidation or phosphorylation of PTEN in RVLM of 12- or 16-week SHR was not significantly different. Likewise, the persistence of PTEN inactivation in RVLM after blood pressure in SHR was normalized implies that it is highly unlikely that hypertension acts as a causal factor.

Although enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM is associated with hypertension in SHR (58), the underlying mechanism remains obscure. PTEN is an intrinsic inhibitor of the PI3K/Akt pathway, acting to degrade PIP3 produced by PI3K before it can activate Akt through phosphorylation (30). We demonstrated in the present study that the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR is attributable to an augmented inactivation of PTEN. Our demonstration of a reduction of redox-sensitive overactivation of PI3K/Akt signaling by the PTEN transgene that possesses no apparent effect on the heightened PI3K activity in RVLM not only reinforces the impact of PTEN inactivation on the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling but implicates an aberrant interplay between the augmented PI3K activity and the reduced PTEN activity in the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR. The minimal changes in PI3K/Akt signaling despite an increase in activity of the phosphatase following overexpression of PTEN transgene in RVLM of WKY rats further suggest that the endogenous PTEN exerts an effective and powerful negative regulation that sustains PI3P at a low level under basal condition. These observations also reinforce the impact of PTEN inactivation on manifestation of the augmented PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR. In the cardiac myocytes, PTEN inactivation increases cell size and growth by amplifying PI3K/Akt signaling; overexpression of PTEN inhibits PI3K/Akt signaling, resulting in decreased cell size (31). In addition, an ascorbate-reversible oxidation of PTEN leads to strong Akt phosphorylation in serum-deprived mouse embryonic fibroblasts (35).

Akt is an important downstream mediator of PI3K and regulates a wide variety of cellular functions in different tissues. Numerous studies have implicated PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling pathways in the regulation of cellular proliferation, migration, differentiation, survival and apoptosis (29, 39, 50, 56). Because of these diverse functions, Akt is tightly regulated as its dysregulation usually leads to disease conditions. Indeed, with respect to the cardiovascular system, an increase in PI3K/Akt signaling is observed in cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure-overload, Fas-ligand or chronic β-adrenergic stimulation (31). Akt is activated on phosphorylation of its Thr-308 and Ser-473 (47). We found in this study that both residues of Akt were phosphorylated by PI3K under a condition of oxidative stress in RVLM of SHR. We further demonstrated that this redox-sensitive activation of PI3K/Akt signaling is specifically regulated by PTEN, because overexpression of PTEN transgene did not affect the redox-sensitive activation of ERK1/2 by Ang II. This is in line with the report (19) of regulation by PTEN on insulin-like growth factor-I-induced activation of Akt but not ERK1/2 in human granulosa cells. However, we noted that PTEN is involved in nerve growth factor-induced activation of both Akt and ERK1/2 in PC-12 cells (21). Taken together, it is conceivable that the downstream signaling molecules regulated by PTEN may be substrate specific, and is dependent on cell types and nature of stimuli. The inability of Ang II to phosphorylate Akt in the presence of wortmannin or LY294002 also deemed a direct action of Ang II or Ang II-induced ROS on Akt phosphorylation unlikely, and supports the notion that ROS activates the PI3K/Akt pathway mainly through PTEN inactivation. This is further consolidated by observations that PTEN siRNA antagonized the reversal of the enhanced PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM of SHR that received antioxidant treatment.

Another novel finding of the present study is that PTEN is causally involved in oxidative stress-associated neurogenic hypertension via a negative modulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in RVLM. We observed that gene knockdown of PTEN by siRNA promoted pressor response in WKY rats. The Ang II-induced and oxidative stress-associated chronic hypertension in normotensive WKY rats was, on the other hand, attenuated by overexpression of PTEN transgene or by gene knockdown of Akt in RVLM. We further showed that site-specific transduction of AdPTEN or gene knockdown of Akt promotes antihypertension in SHR. In addition, antihypertension promoted by p47phox ASON was antagonized by gene knockdown of PTEN in RVLM of SHR, indicating a causal role of PTEN inactivation in the manifestation of redox-sensitive hypertension in SHR. Our findings that PI3K inhibitor (which reduces PIP3) attenuated pressor response in response to PTEN siRNA (which increase PIP3) in RVLM further pointed to the significance of an interplay between PI3K and PTEN in regulating tissue PIP3 and hence the activity of Akt at RVLM in the mediation of oxidative stress-associated neurogenic hypertension. PI3K/Akt signaling cascade has been reported (59) to be directly involved in Ang II-mediated neuritogenesis by stimulating cellular growth-associated protein-43 and neurite extension in brain neurons. It is thus reasonable to speculate that an enhanced activation of PI3K/Akt signaling resultant from redox-associated inactivation of PTEN is crucial to the pathophysiology of neurogenic hypertension via abnormal neuronal connections in RVLM of SHR. In addition, PI3K/Akt signaling may affect neuronal firing activity via the increase in open probability of calcium channels (26) and receptor trafficking of the excitatory ionotrophic glutamate receptors (11). Whether this redox-sensitive aberrant interplay between PI3K and PTEN on enhanced activation of PI3k/Akt signaling takes place in other brain nuclei involved in neural mechanism of hypertension, however, remains to be elucidated.

It has been reported (23) that PTEN negatively regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity via regulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. We reported previously (5) that NO derived from different NOS isoforms in RVLM plays differential roles in brain stem cardiovascular regulation. Whereas neuronal NOS-derived NO induces sympathoexcitation, the inducible NOS is responsible for the sympathoinhibitory effect of NO (5). The eNOS in RVLM, on the other hand, is not actively involved in neural control of blood pressure (9). In view of a dynamic regulation of NO production by different NOS isoforms in neural regulation of blood pressure under physiological and pathological conditions (2, 5, 15, 24), the impact of the aberrant interplay between PTEN and PI3K on regulation of Akt signaling and the downstream NOS activity warrants further investigation. PTEN has also been shown to exert other biological functions, including the induction of apoptosis (1) via activation of PI3K/Akt-dependent or -independent signaling. Activation of PTEN would thus in theory induce apoptosis in RVLM. In this regard, unpublished data from our laboratory demonstrated minor effects of a pan-caspase inhibitor, zVADfmk (50 or 100 pmol) in RVLM on basal SAP in SHR; although activation of pro-apoptotic caspase 3 in RVLM was reported to mediate hypertension in the stroke-prone SHR (25).

In conclusion, we demonstrated in the present study that redox-sensitive inactivation of PTEN results in enhanced activation of PI3K/Akt signaling in RVLM, leading to neurogenic hypertensive phenotype in SHR. High oxygen consumption and a relative weak antioxidant defense system render the central nervous system highly susceptible to oxidative stress. However, the specific mechanisms by which brain oxidative stress leads to neurogenic hypertension are not fully understood. The presence of a novel signal amplification mechanism under oxidative stress revealed by our results is therefore of importance to the pathogenesis of neurogenic hypertension. At the same time, our findings provide a molecular basis for PTEN to be considered a potential therapeutic target for the development of antihypertensives.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were carried out in compliance with the guidelines of the institutional animal care committee of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital. An expanded Materials and Methods section is available in the Supplementary Data.

Animals

Experiments were carried out in adult (12- or 16-weeks old), male SHR (n=286) or age-matched normotensive WKY (n=282) rats purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of the National Applied Research Laboratories, Taiwan. They were housed in an animal room under temperature control (24°C±0.5°C) and 12-h light/dark (08:00–20:00) cycle.

Measurement of systemic arterial pressure and HR by radiotelemetry

SAP and HR were measured for 60 min every day between 14:00 and 15:00 in rats under conscious conditions using a radiotelemetry system (Data Sciences International) (1–5). The averaged value of the 60-min recording was used as the daily value.

Microinjection of test agents into RVLM

Microinjection was carried out with a glass micropipette (external tip diameter: 50–80 μm) connected to a 0.5-μl Hamilton microsyringe. The stereotaxic coordinates for RVLM were: 4.5–5.0 mm posterior to lambda, 1.8–2.1 mm lateral to midline and 8.0–8.5 mm below the dorsal surface of cerebellum (2–6). Test agents used included LY294002 (Sigma-Aldrich); wortmannin (Sigma-Aldrich); CoQ10 (Sigma-Aldrich); Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich); ASON or SON against p47phox (3) (ASON: 5′-TTTGTCTGGTTGTCTGTGGG-3′ and SON, 5′-CCCACAGACAACCAGACAAA-3′; MDBio) or Akt (58) (ASON: 5′-CTTCACAATGGCTACGTCGTT-3′ and SON: 5′-AACGACGTAGCCATTGTGAAG-3′; MDBio); AdPTEN, AdSOD1, AdSOD2 or AdGFP (4, 27); PTEN siRNA (5′-AGAGATCGTTAGCAG AAAC-3′) (36) or scRNA (5′-AGAGACAGAAACTCGTTAG-3′) (16) (MDBio). Microinjection of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) or TurboFact™ (solvent for PTRN siRNA) (Ferments, Inc.) served as the vehicle and volume control.

Microinfusion

Microinfusion of Ang II (Sigma-Aldrich), Akt ASON or SON, CoQ10, tempol (Merck KGaA); LY294002 or Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor was executed by a micro-osmotic minipump (Alzet 1007D; Durect Co.) (8). Control infusion of aCSF served as the volume and vehicle control.

Collection of tissue samples from RVLM

After rats were killed with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneal [i.p.]) and perfused intracardiacly with warm saline, the brain was rapidly removed and immediately frozen on dry ice. As a routine, microinjection sites were visually verified and recorded after the slice of medulla oblongata that contains RVLM (0.5–1.5 mm rostral to the obex) was obtained. Tissues from both sides of the ventrolateral medulla covering RVLM (1.5- to 2.5-mm lateral to the midline and medial to the spinal trigeminal tract) were collected by micropunches with a 1-mm inner diameter burr (2–6, 27). Medullary samples within the boundaries of RVLM thus obtained from five to eight rats under the same experimental treatment were pooled to provide sufficient tissue for protein extraction.

Protein extraction

Total protein from RVLM was extracted with ice-cold lysis buffer. Protease inhibitors were included in the lysis buffer to prevent protein degradation. Proteins extracted were quantified by the Bradford assay with a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) (2–6, 27).

Western blot analysis

Proteins (10 μg) were separated using 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate– polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for 1.5 h at 4°C, using a Bio-Rad miniprotein-III wet transfer unit. The primary antisera used in Western blot analysis included rabbit polyclonal or mouse monoclonal antiserum against PTEN or phosphorylated PTEN (Merck Millipore), Akt or phosphorylated Akt at serine473 or threonine308 (Cell Signaling Technologies), mTOR or phosphorylated mTOR (Cell signaling Technologies), ERK1/2 (Merck) or phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technologies) or α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich). The secondary antisera used included horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) antiserum. Specific antibody-antigen complex was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence Western Blot detection system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp.). The amount of detected protein was quantified by the Photo-Print Plus software (ETS Vilber-Lourmat) (2–6, 27).

Identification of reduced and oxidized form of PTEN by immunoblot analysis

Total protein from RVLM was extracted with a nonreducing extraction buffer, and solubilized proteins were subject to 7% SDS-PAGE under nondenaturing conditions (35). The separated proteins were transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane which was subjected to immunoblot analysis with a rabbit antibody to PTEN (Merck Millipore). Immune complexes were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). The intensity of reduced or oxidized PTEN bands was quantified by the Photo-Print Plus software (ETS Vilber-Lourmat).

PTEN phosphatase assay

Cell lysates from RVLM were incubated with anti-PTEN (Ser-380/Thr-382/Thr-383) antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies) and then with protein-G sepharose beads. The beads were washed with the PTEN reaction buffer, and the PTEN immunoprecipitate was incubated with PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and phosphatidylserine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of N-methylimide. After centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated with Biomol Green™ reagent (Enzo Life Science, Inc.) for 30 min and the color was measured by spectrophotometry at 630 nm (43).

PI3K activity assay

PI3K activity was determined by a PI3K Assay kit (Millipore) according to the manufactory's manual. The captured biotinylated-PIP3 was detected using streptavidin-horseradish peroxide conjugate and the color was measured by spectrophotometry at 450 nm (17).

NADPH oxidase activity

NADPH oxidase activity in RVLM was assayed by a lucigenin chemiluminescence assay according to the previously described procedures (49). Experiments were performed in the presence of apocynin (100 mM), a selective inhibitor of NADPH oxidase. The results were expressed as mean light units/min/100 μg protein.

SOD activity

The activity of SOD in protein fraction from RVLM was measured using a SOD assay kit (Calbiochem) according to manufacturer's instructions. This assay kit utilizes 5,6,6a,11b-tetrahydro-3,9,10-trihydroxybenso[c]fluorine as the substrate. This reagent undergoes alkaline autoxidation, which is accelerated by SOD, and yields a chromophore that absorbs maximally at 525 nm (4).

Measurement of superoxide anion

Extracted proteins were reacted with the oxidation-sensitive fluorescent probe 2-hydroethidium for 15 min. The fluorescence was detected with a fluorescence detector (FluorStar; Biodirect, Inc.) using an emission wavelength of 580 nm and an excitation wavelength of 480 nm.

Isolation of RNA and reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA from RVLM was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and was quantified by spectrophotometry (4, 8, 10). Reverse transcription reaction was performed using a RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed by amplification of cDNA using a LightCycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics). The primers used were designed using Roche LightCycler probe design software 2.0, and were synthesized by Genomics BioSci & Tech. The primer pairs for amplification of PTEN cDNA were: 5′-CACCAGTTCGTCCCTTTCCA-3′ (forward), 5′-TGACAATCATGTTGCAGCAATTC-3′ (reverse) (19); GAPDH cDNA were: 5′-TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG-3′ (forward), 5′-TCACGCCACAGCTTTCCA-3′ (reverse) (4, 8, 10). The PCR products were subsequently subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis for further confirmation of amplification specificity. Fluorescence signals from the amplified products were quantitatively assessed using the LightCycler software program (version 3.5). Second derivative maximum mode was chosen with baseline adjustment set in the arithmetic mode. The relative change in pten mRNA expression was determined by the fold-change analysis (8, 10, 27).

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) under deep pentobarbital anesthesia (100 mg/kg, i.p.), and the brain stem was removed and postfixed in the same solution. 35-μm coronal sections of the rostral medulla oblongata were cut using a cryostat. After preabsorption in gelatin (0.375%), normal horse serum (3%) and Triton X-100 (0.2%) in PBS, the sections were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against PTEN (1:1000; Wako). After incubation in biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch), the sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated with AB complexes (Vectastain ABC elite kit; Vector Laboratories). This was followed by incubation with a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate kit f (Vector Laboratories). Sections were rinsed in PBS and dehydrated by passing through graded series of ethanol and xylene. Sections were mounted and observed under a light microscope (BX53; Olympus optical).

Double immunofluorescence staining and laser confocal microscopy

The procedures for double immunofluorescence staining were similar to those reported previously (6, 9). In brief, free-floating 30-μm sections of the medulla oblongata containing the RVLM were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against PTEN (1:500; Abcam), together with a mouse monoclonal antiserum against a specific neuron marker, neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN) (1:1000; Chemicon), an astrocyte marker, GFAP (1:1000; Dako) or a microglia marker, Iba-1 (1:1000; Wako). The sections were subsequently incubated concurrently with a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 for PTEN, or a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 for NeuN, GFAP or Iba-1. Viewed under a Fluorview FV10i laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus), immunoreactivity for PTEN exhibited green fluorescence and NeuN, GFAP or Iba-1 manifested red fluorescence. The colocalization of red and green fluorescence on merged images indicated double labeling.

Histology

With the exception of animals used for biochemical analyses, the brain stem was removed from animals after they were killed by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, intravenous), and fixed in 10% formaldehyde-saline solution that contained 30% sucrose for ≥72 h. Frozen 25-μm sections of the medulla oblongata were cut using a cryostat and mounted on slide for histological verification of the location of microinjection sites under a light microscope (BX53; Olympus) or for distribution of GFP under a Fluorview FV10i laser scanning confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as means±standard error of the mean. One-way or two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to assess group means, as appropriate, to be followed by the Scheffé multiple-range test for post hoc assessment of individual means. Student's t-test was used to compare the means of two groups. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AdGFP

adenoviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein

- AdPTEN

adenoviral vector encoding PTEN

- AdSOD1

adenoviral vector encoding cupper/zinc superoxide dismutase

- AdSOD2

adenoviral vector encoding mitochondrial SOD

- Akt

serine/threonine protein kinase

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ASON

antisense oligonucleotide

- CoQ10

coenzyme Q10

- DHE

2-hydroethidium

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2

- GAPDH

gylceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HR

heart rate

- i.c.

intracisternal

- i.m.

intramuscular

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- MSAP

mean systemic arterial pressure

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NeuN

neuron-specific nuclear protein

- O2•−

superoxide anion

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- pfu

plaque-forming units

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10

- P-PTEN

phosphorylated PTEN

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla

- scRNA

scrambled small-interfering RNA

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- siRNA

small-interfering RNA

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SON

sense oligonucleotide

- tempol

4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl

- T-PTEN

total PTEN

- WKY

Wistar-Kyoto

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants NSC-100-2321-B-182A-005 (J.Y.H.C.) and NSC-98-2923-B-182A-001-MY3 (S.H.H.C.) from the National Science Council, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Blanco-Aparicio C. Renner O. Leal JF. Carnero A. PTEN, more than the AKT pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1379–1386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan JYH. Wang LL. Chao YM. Chan SHH. Downregulation of basal iNOS at the rostral ventrolateral medulla is innate in SHR. Hypertension. 2003;41:563–570. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000054214.10670.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan SHH. Hsu KS. Huang CC. Wang LL. Ou CC. Chan JYH. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-induced pressor effect via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Circ Res. 2005;97:772–780. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000185804.79157.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan SHH. Tai MH. Li CY. Chan JYH. Reduction in molecular synthesis or enzyme activity of superoxide dismutases and catalase contributes to oxidative stress and neurogenic hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:2028–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SHH. Wang LL. Wang SH. Chan JYH. Differential cardiovascular responses to blockade of nNOS or iNOS in rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:606–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan SHH. Wu CWJ. Chang AYW. Hsu KS. Chan JYH. Transcriptional upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rostral ventrolateral medulla by angiotensin II: significance in superoxide homeostasis and neural regulation of arterial pressure. Circ Res. 2010;107:1127–1139. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan SHH. Wu KLH. Chang AYW. Tai MH. Chan JYH. Oxidative impairment of mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in rostral ventrolateral medulla contributes to neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53:217–227. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan SHH. Wu CA. Wu KLH. Ho YH. Chang AYW. Chan JYH. Transcriptional upregulation of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 protects against oxidative stress-associated neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2009;105:886–896. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AYW. Chan JYH. Chan SHH. Differential distribution of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. J Biomed Sci. 2003;10:285–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02256447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang AYW. Chan JYH. Chou JLJ. Li FCH. Dai KY. Chan SHH. Heat shock protein 60 in rostral ventrolateral medulla reduces cardiovascular fatality during Endotoxemia in the rat. J Physiol. 2006;574:547–564. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen BS. Roche KW. Growth factor-dependent trafficking of cerebellar NMDA receptors via protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylation of NR2C. Neuron. 2009;28:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das X. Dixon JE. Cho W. Membrane-binding and activation mechanism of PTEN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7491–7496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doukas J. Wrasidlo W. Noronha G. Dneprovskaia E. Fine R. Weis S. Hood J. Demaria A. Soll R. Cheresh D. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma/delta inhibition limits infarct size after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19866–19871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606956103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goncharova EA. Ammit AJ. Irani C. Carroll RG. Eszterhas AJ. Panettieri RA. Krymskaya VP. PI3K is required for proliferation and migration of human pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L354–L363. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo ZL. Tjen-A-Looi SC. Fu LW. Longhurst JC. Nitric oxide in rostral ventrolateral medulla regulates cardiac-sympathetic reflexes: role of synthase isoforms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1478–H1486. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00209.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J. Kontos CD. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration and survival by the tumor suppressor protein PTEN. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:745–751. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000016358.05294.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang W. Jiang D. Wang X. Wang K. Sims CE. Allbritton NL. Zhang Q. Kinetic analysis of PI3K reactions with fluorescent PIP2 derivatives. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;401:1881–1888. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5257-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huo YY. Li G. Duan RF. Gou Q. Fu CL. Hu YC. Song BQ. Yang ZH. Wu DC. Zhou PK. PTEN deletion leads to deregulation of antioxidants and increased oxidative damage in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1578–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwase A. Goto M. Harata T. Takigawa S. Nakahara T. Suzuki K. Manabe S. Kikkawa F. Insulin attenuates the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I)-Akt pathway, not IGF-I-extracellularly regulated kinase pathway, in luteinized granulosa cells with an increase in PTEN. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2184–2191. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen BJ. Kam KL. Smits JF. Preferential renal and mesenteric vasodilation induced by barnidipine and amlodipine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:414–421. doi: 10.1007/s002100100468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia L. Ji S. Maillet JC. Zhang X. PTEN suppression promotes neurite development exclusively in differentiating PC12 cells via PI3-kinase and MAP kinase signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1390–1400. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang KH. Lemke G. Kim JW. The PI3K-PTEN tug-of-war, oxidative stress and retinal degeneration. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyes KT. Xu J. Long B. Zhang C. Hu Z. Ye Y. Pharmacological inhibition of PTEN limits myocardial infarct size and improves left ventricular function postinfarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1198–H1208. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00915.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura Y. Hirooka Y. Sagara Y. Ito K. Kishi T. Shimokawa H. Takeshita A. Sunagawa K. Increased reactive oxygen species in rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to neural mechanisms of hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation. 2004;109:2357–2362. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128695.49900.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishi T. Hirooka Y. Konno S. Ogawa K. Sunagawa K. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor activated caspase-3 through Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla is involved in sympathoexcitation in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2010;55:291–297. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koulen P. Madry C. Duncan RS. Hwang JY. Nixon E. McClung N. Gregg EV. Singh M. Progesterone potentiates IP3-mediated calcium signaling through Akt/PKB. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;21:161–172. doi: 10.1159/000113758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kung LC. Chan SHH. Wu KLH. Ou CC. Tai MH. Chan JYH. Mitochondrial respiratory enzyme complexes in rostral ventrolateral medulla as cellular targets of nitric oxide and superoxide interaction in the antagonism of antihypertensive action of eNOS transgene. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1319–1332. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwon J. Lee SR. Yang KS. Ahn Y. Kim YS. Stadtman ER. Rhee SG. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN in cells stimulated with peptide growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16419–16424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407396101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latronico MV. Costinean S. Lavitrano ML. Peschle C. Condorelli G. Regulation of cell size and contractile function by AKT in cardiomyocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:250–260. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SR. Yang KS. Kwon J. Lee C. Jeong W. Rhee SG. Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20336–20342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leslie NR. Bennett D. Lindsay YE. Stewart H. Gray A. Downes CP. Redox regulation of PI3-kinase signalling via inactivation of PTEN. EMBO J. 2003;22:5501–5510. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leslie NR. Downes CP. PTEN: the down side of PI3-kinase signalling. Cell Signal. 2002;14:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li DM. Sun H. TEP1, encoded by a candidate tumor suppressor locus, is a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase regulated by transforming growth factor β. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2124–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J. Yen C. Liaw D. Podsypanina K. Bose S. Wang SI. Puc J. Miliaresis C. Rodgers L. McCimbie R. Bigner SH. Giovanella BC. Ittmann M. Tycko B. Hibshoosh H. Wigler MH. Parsons R. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim S. Clement MV. Phosphorylation of the survival kinase Akt by superoxide is dependent on an ascorbate-reversible oxidation of PTEN. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1178–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B. Li L. Zhang Q. Chang N. Wang D. Shan Y. Li L. Wang H. Feng H. Zhang L. Brann DW. Wan Q. Preservation of GABAA receptor function by PTEN inhibition protects against neuronal death in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2010;41:1018–1026. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maehama T. Dixon JD. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayorov DN. Brain superoxide as a key regulator of the cardiovascular response to emotional stress in rabbits. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:471–479. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.036830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDowell SA. McCall E. Matter WF. Estridge TB. Vlahos CJ. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates excitation-contraction coupling in neonatal cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H796–H805. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00546.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mourani PM. Garl PJ. Wenzlau JM. Carpenter TC. Stenmark KR. Weiser-Evans MC. Unique, highly proliferative growth phenotype expressed by embryonic and neointimal smooth cells is driven by constitutive Akt, mTOR, and p70S6K signaling and is actively repressed by PTEN. Circulation. 2004;109:1299–1306. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118462.22970.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Namgaladze D. Brüne B. Phospholipase A2-modified low-density lipoprotein activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway and increases cell survival in monocytic cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2510–2516. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000245797.76062.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Northcott CA. Hayflick JS. Watts SW. PI3-kinase upregulation and involvement in spontaneous tone in arteries from DOCA-salt rats: is p110δ the culprit? Hypertension. 2004;43:885–890. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118518.20331.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oinuma I. Ito Y. Katoh H. Negishi M. Semaphorin 4D/Plexin-B1 stimulates PTEN activity through R-RasGTPase-activating protein activity, inducing growth cone collapse in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28200–28209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oudit GY. Sun H. Kerfant BG. Crackower MA. Penninger JM. Backx PH. The role of phosphoinositide-3 kinase and PTEN in cardiovascular physiology and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:449–471. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelicano H. Xu RH. Du M. Feng L. Sasaki R. Carew JS. Hu Y. Ramdas L. Hu L. Keating MJ. Zhang W. Plunkett W. Huang P. Mitochondrial respiration defects in cancer cells cause activation of Akt survival pathway through a redox-mediated mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:913–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perrino C. Schroder JN. Lima B. Villamizar N. Nienaber JJ. Milano CA. Naga Prasad SV. Dynamic regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-gamma activity and beta-adrenergic receptor trafficking in end-stage human heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:2571–2579. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Persad S. Attwell S. Gray V. Mawji N. Deng JT. Leung D. Yan J. Sanghera J. Walsh MP. Dedhar S. Regulation of protein kinase B/Akt-serine 473 phosphorylation by integrin-linked kinase: critical roles for kinase activity and amino acids arginine 211 and serine 343. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27462–27469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross CA. Ruggiero DA. Park DH. Joh TH. Sved AF. Fernandez-Pardal J. Saavedra JM. Reis DJ. Tonic vasomotor control by the rostral ventrolateral medulla: effect of electrical and chemical stimulation of the area containing C1 adrenaline neurons on arterial pressure, heart rate and plasma catecholamine and vasopressin. J Neurosci. 1984;4:474–494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-02-00474.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satoh M. Ogita H. Takeshita K. Mukai Y. Kwiatkowski DJ. Liao JK. Requirement of Rac1 in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510444103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saward L. Zahradka P. Angiotensin II activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1997;81:249–257. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheid MP. Woodgett JR. Unravelling the activation mechanisms of protein kinase B/Akt. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:108–112. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott PH. Brunn GJ. Kohn AD. Roth RA. Lawrence JC., Jr. Evidence of insulin-stimulated phosphorylation and activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin mediated by a protein kinase B signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7772–7777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seyedabadi M. Goodchild AK. Pilowsky PM. Differential role of kinases in brain stem of hypertensive and normotensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;38:1087–1092. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.096054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sirker A. Zhang M. Shah AM. NADPH oxidase in cardiovascular disease: insights from in vivo models and clinical studies. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:735–747. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0190-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song P. Wu Y. Xu J. Xie Z. Dong Y. Zhang M. Zou MH. Reactive nitrogen species induced by hyperglycemia suppresses Akt signaling and triggers apoptosis by upregulating phosphatase PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10) in an LKB1-dependent manner. Circulation. 2007;116:1585–1595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugden PH. Ras, Akt, and mechanotransduction in the cardiac myocyte. Circ Res. 2003;93:1179–1192. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000106132.04301.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vazquez F. Grossman SR. Takahashi Y. Rokas MV. Nakamura N. Sellers WR. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail acts as an inhibitory switch by preventing its recruitment into a protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48627–48630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Veerasingham SJ. Yamazato M. Berecek KH. Wyss JM. Raizada MK. Increased PI3-kinase in presympathetic brain areas of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circ Res. 2005;96:277–279. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156275.06641.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang H. Shaw G. Raizada MK. Ang II stimulation of neuritogenesis involves protein kinase B in brain neurons. Am J Physiol Integrative Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R107–R114. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00611.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Y. Hoell P. Ahlemeyer B. Sure U. Bertalanffy H. Krieglstein J. Implication of PTEN in production of reactive oxygen species and neuronal death in vitro models of stroke and Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.