Abstract

Objective

To determine the toxicity and effectiveness of 24 months of adjuvant temozolomide (tmz) with cis-retinoic acid (cra) for patients with glioblastoma.

Methods

This retrospective population-based review considered the charts of all patients diagnosed with glioblastoma in Manitoba and referred to a provincial cancer centre during 2002–2008. Consecutive patients came from a population-based referral centre and provincial cancer registry.

All patients were treated according to the local standard of care with surgical resection followed by concurrent radiotherapy and tmz 75 mg/m2 daily, followed by tmz 150–200 mg/m2 for days 1–5, repeated every 28 days for up to 24 cycles, and cra 50 mg/m2 twice daily for days 1–21, repeated every 28 days.

The main outcome measures were safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of long-term tmz and cra.

Results

Of 247 patients diagnosed with glioblastoma in Manitoba during the study period, 116 started concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and 80 received adjuvant tmz. Of the patients who started concurrent chemoradiotherapy, 80 began adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients completed a median of 5.5 cycles of tmz and 3 cycles of cra. Grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicity was noted in 16% of patients. Median overall survival was 15.1 months, and 26.7% of patients remained alive at 2 years.

Conclusions

Extended adjuvant tmz and cra is well tolerated. However, the population-based effectiveness of this regimen is similar to the clinical trial efficacy of 6 months of adjuvant tmz. Future studies in glioblastoma should incorporate duration of adjuvant chemotherapy into the study design.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, temozolomide, duration of therapy, cis-retinoic acid, dose density

1. INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive primary cancer of the central nervous system. The standard of care includes the use of postoperative radiotherapy with concurrent temozolomide, followed by further adjuvant temozolomide. The pivotal study by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the National Cancer Institute of Canada (eortc/ncic), used 6 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide and found, compared with treatment using radiation alone, a statistically significant improvement in median overall survival (os) from 12.1 months to 14.6 months1. Despite this advance, long-term survival remains poor, with only 9.8% of patients remaining alive at 5 years2.

The optimal duration of adjuvant chemotherapy remains uncertain. The 6 cycles in the eortc/ncic trial were based on the favourable phase ii study of first-line temozolomide and concurrent radiotherapy3. No randomized comparison has been made of the standard 6 cycles of temozolomide compared with longer or shorter durations. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0525 study that compared newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients receiving standard (5-day) or dose-dense (21-day) treatment schedules did not demonstrate a difference in outcome4. Study investigators chose between 6 and 12 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide; a secondary analysis of outcomes based on duration of therapy is anticipated. A recent retrospective institutional study found an association between longer survival and 12 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide compared with 6 cycles5.

Standard adjuvant therapy in many solid tumours typically lasts for 6 or fewer months6–8; however, the extremely high rate of relapse in glioblastoma may argue for a longer duration of therapy, such as those used in metastatic colorectal or breast tumours9. Furthermore, the tolerability of temozolomide may allow for a longer duration of therapy and for further gains in survival with little impact on quality of life1,3,10,11. Despite limited data5,12,13, many centres use 12 or more months of adjuvant temozolomide as their standard therapy, and yet it remains unclear whether extended-duration temozolomide is safe or effective.

Isotretinoin (cis-retinoic acid), a ligand for the retinoic acid receptor, has been studied in the treatment of malignant gliomas. In glioma cells, cis-retinoic acid may induce differentiation and inhibit proliferation and invasiveness14–16. It may also increase the sensitivity of glioblastoma cells to conventional chemotherapy17. As a single agent, cis-retinoic acid has shown modest benefits in maintaining remission in malignant glioma18–20. Combination therapy with temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid at recurrence has shown considerable promise, yielding a 6-month progression-free survival (pfs-6) of 43% in a large phase ii study from the North American Brain Tumor Consortium21. However, that study antedated the use of temozolomide in chemoradiation strategies for newly diagnosed patients. In the upfront setting, the combination conferred a pfs-6 of 38% and a 1-year os of 57%, similar to that seen in phase ii studies with other agents22. The combination of temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid was tolerated well in both studies.

CancerCare Manitoba is a regional Canadian cancer centre with a catchment population of approximately 1.5 million. All patients with a brain tumour receive multimodal therapy at the same tertiary care centre. Since the publication of the phase ii upfront temozolomide data in 20023, standard treatment of patients with glioblastoma in the adjuvant setting in Manitoba has included radiotherapy with concurrent temozolomide, followed by up to 24 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide with concurrent cis-retinoic acid. Here, we retrospectively evaluate this consecutively enrolled patient cohort for their outcomes and the toxicity associated with extended-duration temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient Cohort

Records for all patients with a pathologic diagnosis of glioblastoma in Manitoba from January 1, 2002, to June 30, 2008, were extracted from the Manitoba Cancer Registry. Clinic lists were searched for all new patient visits during the same period to ensure capture of all patients referred. The protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board, University of Manitoba, and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Electronic and paper records were reviewed for all patients. Sex, histology, and dates of birth, diagnosis, and death were obtained. For each patient in the adjuvant cohort, the following data were extracted from the patient chart: dates of birth, diagnosis, progression and death; sex; number of cycles of temozolomide and of cis-retinoic acid received (including dates and dose); dose and schedule of radiation; extent of surgical resection (resection vs. biopsy); tumour location (frontal vs. non-frontal); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; chemotherapy at relapse; and durations of treatment. Performance status was determined from the record of the initial patient visit and dichotomized as either “good” (0–2) or “poor” (3–4).

2.2. Treatment Protocol

Standard therapy in Manitoba during the study period consisted of surgical resection followed by radiotherapy (conformal external-beam radiation of 60 Gy) with concurrent temozolomide (75 mg/m2 daily during radiotherapy), followed by temozolomide (150–200 mg/m2 daily, days 1–5 of a 28-day cycle) for up to 24 cycles or until evidence of disease progression. While on adjuvant temozolomide, patients were given concurrent cis-retinoic acid (50 mg/m2 twice daily, days 1–21 of each cycle), as tolerated.

2.3. Follow-Up

All patients were followed monthly by the Brain Tumour Disease Site Group at CancerCare Manitoba. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed every 8–12 weeks. Progression dates were recorded as the date of the multidisciplinary case conference (attended by members from radiation oncology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, neuro-radiology, and allied health care providers) during which patients were determined to have had progression of disease according to the Macdonald criteria (which were in place during the study period, before the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology criteria were introduced)23,24.

2.4. Outcomes and Statistics

The primary outcome was os. Secondary outcomes included pfs and toxicity (thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, rash, acute leukemia, elevated liver enzymes, and depression requiring pharmacologic intervention).

To assess the effectiveness of a longer duration of temozolomide on survival, a landmark analysis was performed on all patients in our cohort surviving 6 months or more after initiation of the adjuvant temozolomide and on the published (not individual patient) data from the eortc/ncic trial2. Patient outcomes were compared using the Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel method, stratified at 12, 18, and 24 months from diagnosis. This test allowed us to compare the proportions of patients living and dead in each cohort, while controlling for the fact that the rate may change over time. This methodology effectively compares patients who might have been eligible for more than 6 cycles of temozolomide in the eortc/ncic study with the patients in our cohort who received it25. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards modelling was used to determine the effect of individual prognostic variables on survival.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cohort

Our cohort included 116 patients who started chemoradiotherapy. From that group, 80 patients went on to receive adjuvant temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid. Table i outlines the cohort demographics. Outcomes were ascertained up to December 1, 2010.

TABLE I.

Patient and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic |

Treatment with

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoradiotherapy | Adjuvant tmz and cra | ||

| Patients (n) | 116 | 80 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 58 | 58 | |

| Range | 19–69 | 19–69 | |

| Age groups [n (%)] | |||

| <50 Years | 30 (26) | 24 (30) | |

| ≥50 Years | 86 (74) | 56 (70) | |

| Sex [n (%)] | |||

| Male | 69 (59) | 50 (62.5) | |

| Female | 47 (41) | 30 (37.5) | |

| Tumour location [n (%)] | |||

| Frontal | 29 (36) | ||

| Parietal | 5 (6) | ||

| Temporal | 14 (18) | ||

| Occipital | 1 (1) | ||

| Multiple lobes or central | 31 (39) | ||

| Extent of surgery [n (%)] | |||

| Biopsy | 13 (16) | ||

| Partial resection | 53 (66) | ||

| Complete resection | 14 (18) | ||

| Time from Dx to rt (weeks) | |||

| Median | 3 | ||

| Range | 1.1–8.3 | ||

| Radiation dose (Gy) | |||

| Median | 60 | ||

| Range | 37.5–60 | ||

| Fractions (n) | |||

| Median | 30 | ||

| Range | 15–33 | ||

| Chemoradiotherapy duration (days) | |||

| Median | 44 | ||

| Range | 20–54 | ||

| Interruption or delay [n (%)] | 9 (11.4) | ||

|

|

|||

| Chemotherapy | tmz | cra | |

|

|

|||

| Started adjuvant [n (%)] | 80 (100) | 63 (78.75) | |

| Dose-escalated to 200 mg/m2 [n (%)] | 61 (76.25) | — | |

| Duration [n (%)] | |||

| Median (cycles) | 5.5 | 3 | |

| Range (cycles) | 1–30 | 0–30 | |

| 6 Cycles | 40 (50) | 30 (37.5) | |

| 12 Cycles | 18 (22.5) | 17 (21.25) | |

| 18 Cycles | 13 (16.25) | 12 (15) | |

| 24 Cycles | 10 (12.5) | 6 (7.5) | |

| 30 Cycles | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | |

tmz = temozolomide; cra = cis-retinoic acid; Dx = diagnosis; rt = radiotherapy.

3.2. Treatment

Table i outlines treatment details. The median time from surgery to chemoradiotherapy was 3 weeks (range: 1.1–8.3 weeks). Radiotherapy doses of 59.4–60 Gy were achieved in all but 5 patients, in whom the dose was reduced because of poor performance status. Patients received a median of 5.5 cycles of temozolomide (range: 1–30 cycles) and 3 cycles of cis-retinoic acid (range: 1–30 cycles). Two patients (2.5%) received 30 cycles of both agents. At relapse, chemotherapy was given to 44 patients, with 55%, 21.2%, and 3.8% receiving second-, third-, and fourth-line chemotherapy respectively. The chemotherapy agents used included carboplatin, tamoxifen, celecoxib, temozolomide, procarbazine, thioguanine, hydroxyurea, lomustine, polifeprosan 20 with carmustine implant, and the study drugs edotecarin and cintredekin besudotox (IL-13–PE38QQR) administered by convection-enhanced delivery. Surgery was performed at recurrence in 17 patients (21.2%).

3.3. Outcomes

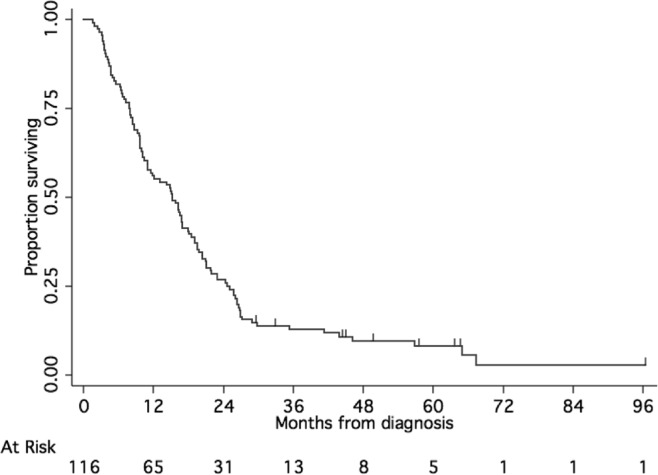

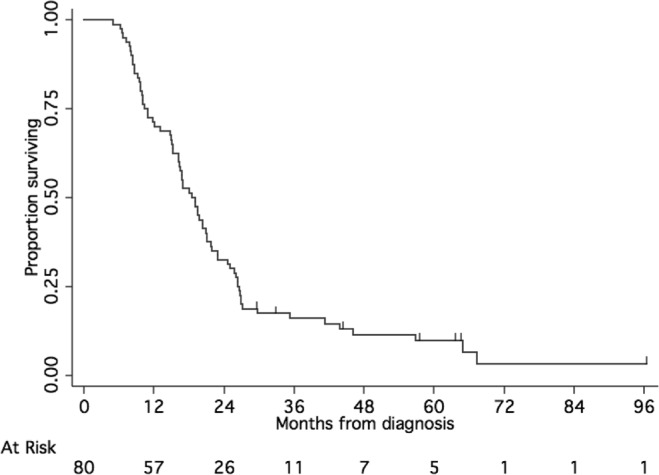

Median os for all 116 patients was 15.1 months [95% confidence interval (ci): 11.0 to 18 months], with 26.7% of patients remaining alive at 24 months (Figure 1). In the 80 patients who received temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid, median pfs was 9.6 months (95% ci: 8.6–11.7 months), and median os was 18.8 months (95% ci: 16.3–21.1 months; Figure 2). At 24 months, 15% of the patients were alive without progression, and 32.5% remained alive.

FIGURE 1.

Overall survival of all patients treated with radiation and concurrent temozolomide.

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival of subset of patients treated with adjuvant temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid.

The landmark analysis was performed using all patients surviving 6 months or more (n = 95) and comparing them with members of the intention-to-treat population from the eortc/ncic trial who survived 6 months or more (n = 247). The Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel analysis demonstrated no statistically significant effect of extended-duration temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid on survival (Table ii).

TABLE II.

Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel landmark analysis

| Variable |

Probability of survival (%)

|

Survival ratio (95% ci) |

Probability of survival (%), landmark group

|

Survival ratio (95% ci) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eortc/ncic (n=287) | mb (n=116) | eortc/ncic (n=247) | mb (n=95) | |||

| 6-Month | 86.3 | 81.9 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) | —a | —a | —a |

| 12-Month | 70.7 | 68.4 | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.21) | 70.7 | 68.4 | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.21) |

| 18-Month | 64.5 | 73.8 | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.05) | 64.5 | 73.9 | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.05) |

| 24-Month | 67.0 | 64.6 | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.34) | 67.1 | 64.6 | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.34) |

| Overall | 74.6 | 73.8 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) | 68.0 | 69.2 | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) |

To be included in the landmark group, patients had to survive to the 6-month mark, and therefore survival and survival ratio are not reported at that time point.

eortc/ncic = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and National Cancer Institute of Canada joint study; mb = present Manitoba cohort; ci = confidence interval.

The final Cox proportional hazards multivariate model included age at diagnosis, extent of surgery, and date of diagnosis (with the study period divided into 3 equal strata). Significantly worse survival was experienced by patients in the middle-year diagnosis group than by patients in the early-year diagnosis group, with a hazard ratio for death of 1.84 in the former group (p = 0.05, Table iii). Outcomes tended to be better in patients undergoing surgical resection than in those undergoing biopsy (hazard ratio: 0.53; p = 0.06).

TABLE III.

Multivariate analysis

| Variable | hr | 95% ci | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.05 | 0.12 |

| Resection vs. biopsy | 0.53 | 0.27 to 1.03 | 0.06 |

| Middle vs. early time period | 1.84 | 1.00 to 3.40 | 0.05 |

| Late vs. early time period | 1.63 | 0.86 to 3.08 | 0.14 |

hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval.

3.4. Toxicity

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicity occurred in 16% of patients (thrombocytopenia, 13.8%; neutropenia, 8.8%; anemia, 8.8%). Treatment delays because of between-cycle toxicity occurred in 29 patients. Of 671 total cycles given, 8.6% were delayed because of toxicity, almost exclusively because of cytopenia. No patient discontinued temozolomide because of intolerance, but 46.3% of patients discontinued cis-retinoic acid because of intolerance, most often consisting of rash. Of patients who discontinued cis-retinoic acid, the mean number of temozolomide cycles given without cis-retinoic acid was 3.8 (median: 2 cycles; range: 1–24 cycles).

While taking cis-retinoic acid, 4 patients required an antidepressant for treatment of clinical depression. During temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid treatment, 8 patients developed significant rash, and 8 patients developed elevated alanine aminotransferase (>5 times the upper limit of normal); another 5 experienced the latter side effect when taking temozolomide alone. During temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid treatment, 3 patients developed elevated bilirubin (>5 times the upper limit of normal). No patient developed acute leukemia or Pneumocystis jiroveci infection during follow-up.

4. DISCUSSION

Here, we report the population-based outcomes of glioblastoma patients treated with up to 24 months of temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid after surgery and radiation therapy in the upfront setting. Treatment with this extended-duration adjuvant therapy resulted in a median os of 15.1 months, a 2-year os of 26.7%, and modest hematologic and systemic toxicity.

Similar survival results have been reported from other reviews of the long-term use of temozolomide alone12,13, supporting our findings. A recent retrospective study from another Canadian tertiary referral centre examined the outcomes of patients before and after a change in policy that allowed for up to 12 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide5. In that cohort, median survival rose to 24.6 months from 16.5 months with longer durations of therapy, suggesting a benefit in extending temozolomide beyond the 6-cycle standard. However, because of the study design, it is possible that some patients who received more than 6 cycles may not have incurred additional benefit from extended therapy.

Our results are similar to those achieved by the current standard of up to 6 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide1. Median os for the 6-cycle regimen was 14.6 months, with a 2-year os of 27.2%2. Basic demographics were comparable between the 6-cycle group and our cohort, as were the percentages of patients completing 6 cycles of temozolomide in the two studies (47% in the eortc/ncic trial and 50% in our cohort). We used a 6-month landmark analysis to assess the effect of longer treatment durations by comparing survival ratios for patients who survived longer than the first 6 months of therapy in the eortc/ncic study and in our cohort. The outcomes of patients from the eortc/ncic trial who were alive at 6 months (and who, per protocol, received no further temozolomide) were compared with those of the patients in our adjuvant cohort who continued to receive temozolomide. Although not randomized, the comparison is reasonable given the similarity of the cohort demographics. It provides a relatively unbiased comparison of these otherwise similar groups25, although it uses specific time points for comparison and therefore has less statistical power than that of a standard log-rank test. Our results suggest that the effectiveness of extended-duration temozolomide with cis-retinoic acid provided in a provincial cancer centre is at least similar to the clinical trial efficacy observed with 6 months of temozolomide. Any potential difference in survival with a longer duration of chemotherapy is not likely to be clinically meaningful, prompting a post-analysis change in our local standard to 12 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide without cis-retinoic acid; treatment beyond 12 cycles is considered only when there is evidence of an ongoing treatment response.

Our study has a number of limitations. Selection bias is inherent in the comparison of a retrospective cohort with the results of a prospective randomized trial. Patients in our study were treated based on the clinician’s assessment of suitability (predominantly age and performance status). Given that only 69% of our overall cohort proceeded to receive adjuvant temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid, compared with 78% of the eortc/ncic trial cohort, it is likely that our results are overly pessimistic. Molecular prognostic factors, such as MGMT promoter methylation, were not available for our cohort, and their impact on survival in our population remains unknown. The concept of pseudoprogression was not well described during the early years of our study cohort, and it is more than likely that some patients who progressed early actually had pseudoprogression, further negatively biasing our results. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we are unable to discern the independent effect of extended adjuvant temozolomide compared with the addition of cis-retinoic acid. Despite those limitations, our data suggest that any advantage to a longer duration of temozolomide is probably small. No firm conclusions can be made, and a large randomized study both of treatment duration and of the addition of cis-retinoic acid would be required to fully assess any potential difference. A planned analysis of the randomized Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0525 study4 for the effect of 6 compared with 12 cycles of adjuvant temozolomide is awaited and may provide evidence for one approach over the other.

The modest toxicity noted in our cohort is reassuring; extended durations of temozolomide are well tolerated. Only 13 patients demonstrated significant hematologic toxicities, with 6 patients accounting for most of those events. That finding suggests an underlying susceptibility of some patients to hematologic toxicity, perhaps relating to underlying differences in O6-methylguanine-dna methyltransferase activity in the bone marrow of those patients or to other factors26. Non-hematologic toxicity was minimal, with few patients experiencing significant side effects from temozolomide. Similarly, little toxicity with cis-retinoic acid was noted. As expected, toxicities included dry skin, depression, and elevated liver enzymes. Despite those side effects, most patients continued on therapy for the duration of their adjuvant treatment.

Our multivariate analysis of patients who received at least 1 adjuvant cycle of temozolomide demonstrated few clear prognostic factors. The extent of surgical resection was not a statistically significant predictor of survival, and yet there was a very strong trend in favor of resection compared with biopsy (p = 0.06). That finding is consistent with the existing literature on surgical resection for adult glioma, although no randomized data are available to support a causal effect27–30. It remains possible that some of the effect is a result of very poor survival in patients in whom surgical resection was not possible.

The present study did not demonstrate a significant improvement in the survival of patients in more recently treated cohorts. That result does not support assertions that similar survival advantages noted in recent phase ii studies from the New Approaches to Brain Tumor Therapy Consortium are attributable to improvements in patient survival over time rather than to the therapeutic agents under study. The improvements might be attributable to any or a combination of enhanced surgical and anesthetic technologies, neuroimaging, and supportive care31. Our multivariate analysis trended in the opposite direction, suggesting a possible worsening of survival for more recent cohorts. That difference might partly be explained by differing patient populations: ours was an unselected population-based Canadian cohort; the New Approaches to Brain Tumor Therapy Consortium clinical trials involved highly selected participants from the United States. We note in our data that biopsy-only surgical procedures were more common in recent cohorts, which may also explain the result reported here. Our limited cohort size constrained the power of our analysis, and we were unable to fully account for specific local factors—such as the interaction between extent of resection and date of diagnosis—that, compared with the same factors in large multicentre studies, might influence outcomes.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We have described the long-term use of temozolomide combined with cis-retinoic acid for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. The regimen did not create undue toxicity for patients. The particular advantages of extending adjuvant therapy are not clear from the present study; however, our data provide some rationale for further study of this treatment paradigm—in the context of a clinical trial. As new agents are studied in combination with adjuvant temozolomide, the duration of such therapies should be part of the study design.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The results and conclusions presented are those of the authors. No official endorsement by Manitoba Health is intended or should be inferred. This work was supported by the Dr. Paul H.T. Thorlakson Fund (ML), the Dr. James Pullar Memorial Trust (BH), the Dr. John Adamson and Dr. Sanford T. Fleming Studentship (BH), and the Reverend Thomas Alfred Payne Memorial Fund (BH). The authors also acknowledge the support of the Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have declared no financial conflicts of interest.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. on behalf of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. on behalf of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase iii study: 5-year analysis of the eortc–ncic trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Dietrich PY, Ostermann Kraljevic S, et al. Promising survival for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme treated with concomitant radiation plus temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1375–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.5.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert MR, Wang M, Aldape KA, et al. rtog 0525: a randomized phase iii trial comparing standard adjuvant temozolomide (tmz) with a dose-dense (dd) schedule in newly diagnosed glioblastoma (gbm) [abstract 2006] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=102&abstractID=79659; cited September 12, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roldán Urgoiti GB, Singh AD, Easaw JC. Extended adjuvant temozolomide for treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2012;108:173–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (ebctcg) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.André T, Boni C, Mounedji–Boudiaf L, et al. on behalf of the Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer (mosaic) investigators Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) Breast Cancer NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2012. Ver 3.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taphoorn MJ, Stupp R, Coens C, et al. on behalf of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour Group, the eortc Radiotherapy Group, and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Health-related quality of life in patients with glioblastoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:937–44. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osoba D, Brada M, Yung WK, Prados M. Health-related quality of life in patients treated with temozolomide versus procarbazine for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1481–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seiz M, Krafft U, Freyschlag CF, et al. Long-term adjuvant administration of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: experience of a single institution. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:1691–5. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0827-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hau P, Koch D, Hundsberger T, et al. Safety and feasibility of long-term temozolomide treatment in patients with high-grade glioma. Neurology. 2007;68:688–90. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000255937.27012.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reboul P, George P, Louisot P, Broquet P. Study of retinoic acid effect upon retinoic acid receptors beta (rar-beta) in C6 cultured glioma cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1995;36:1097–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouterfa H, Picht T, Kess D, et al. Retinoids inhibit human glioma cell proliferation and migration in primary cell cultures but not in established cell lines. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:419–30. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200002000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodts GE, Jr, Black KL. Trans retinoic acid inhibits in vivo tumour growth of C6 glioma in rats: effect negatively influenced by nerve growth factor. Neurol Res. 1994;16:184–6. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1994.11740223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das A, Banik NL, Ray SK. Retinoids induced astrocytic differentiation with down regulation of telomerase activity and enhanced sensitivity to taxol for apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells. J Neurooncol. 2008;87:9–22. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wismeth C, Hau P, Fabel K, et al. Maintenance therapy with 13-cis retinoid acid in high-grade glioma at complete response after first-line multimodal therapy—a phase-ii study. J Neurooncol. 2004;68:79–86. doi: 10.1023/B:NEON.0000024748.26608.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yung WK, Kyritsis AP, Gleason MJ, Levin VA. Treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas with high-dose 13-cis-retinoic acid. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1931–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke JL, Iwamoto FM, Sul J, et al. Randomized phase ii trial of chemoradiotherapy followed by either dose-dense or metronomic temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3861–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaeckle KA, Hess KR, Yung WK, et al. Phase ii evaluation of temozolomide and 13-cis-retinoic acid for the treatment of recurrent and progressive malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2305–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butowski N, Prados MD, Lamborn KR, et al. A phase ii study of concurrent temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid with radiation for adult patients with newly diagnosed supratentorial glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase ii studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1277–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1963–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dafni U. Landmark analysis at the 25-year landmark point. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:363–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerson SL, Miller K, Berger NA. O6-Alkylguanine-dna alkyltransferase activity in human myeloid cells. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:2106–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI112215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:190–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senft C, Franz K, Blasel S, et al. Influence of imri-guidance on the extent of resection and survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2010;9:339–46. doi: 10.1177/153303461000900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Wang M, Won M, et al. Validation and simplification of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group recursive partitioning analysis classification for glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:623–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanai N, Berger MS. Operative techniques for gliomas and the value of extent of resection. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:478–86. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossman SA, Ye X, Piantadosi S, et al. on behalf of the nabtt cns Consortium Survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated with radiation and temozolomide in research studies in the United States. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2443–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]