Abstract

Background

In the U.K. Medical Research Council Myeloma IX trial (mmix), zoledronic acid 4 mg once every 3–4 weeks, compared with clodronate 1600 mg daily, reduced the incidence of skeletal related events (sres), increased progression-free survival (pfs), and prolonged overall survival (os) in 1970 patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. The incidence of confirmed osteonecrosis of the jaw was higher with zoledronic acid than with clodronate. The objective of the present study was to evaluate, based on the findings in mmix, the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid compared with clodronate in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Methods

An economic model was used to project pfs, os, the incidence of sres and adverse events, and expected lifetime health care costs for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are alternatively assumed to receive zoledronic acid or clodronate. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (icer) of zoledronic acid compared with clodronate was calculated as the ratio of the difference in cost to the difference in quality-adjusted life years (qalys). Model inputs were based on results of mmix and published sources. Results were generated under different assumptions regarding the beneficial effects of zoledronic acid on os beyond 5 years after treatment initiation.

Results

Assuming lifetime treatment effects of zoledronic acid, treatment with zoledronic acid (compared with clodronate) increased qalys by 0.27 at an additional cost of CA$13,407, yielding an icer of CA$49,829 per qaly gained. If the threshold icer is CA$100,000 per qaly, the estimated probability that zoledronic acid is cost-effective is 80%. Assuming that the benefits of zoledronic acid on pfs and os diminish over 5 years beginning at the end of year 5, the icer is CAN$63,027 per qaly gained. If the benefits of zoledronic acid on pfs and os are assumed to persist for 5 years only, the icer is CAN$76,948 per qaly gained.

Conclusions

Compared with clodronate, zoledronic acid represents a cost-effective treatment alternative in patients with multiple myeloma.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, zoledronic acid, clodronate, bisphosphonates, cost-effectiveness

1. INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma is a B-cell malignancy in which abnormal plasma cells accumulate in bone marrow. In Canada in 2008, 2100 new cases of multiple myeloma were diagnosed, and 1350 associated deaths occurred1. Prognosis in multiple myeloma is highly variable and depends on stage at diagnosis and other factors. The age-standardized 5-year relative survival ratio for multiple myeloma in Canada for the 2004–2006 period was 37%1.

Treatments for multiple myeloma include autologous stem-cell transplantation, chemotherapy, corticosteroids, immunomodulating agents such as thalidomide and lenalidomide, and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Maintenance treatment may be used after chemotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation to prolong response. High-dose therapy with allogenic stem-cell transplantation using a sibling donor may also be an option for some younger patients. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that adding bisphosphonates to standard treatment for multiple myeloma reduces pain and the risk of skeletal-related events (sres), where sres are typically defined as hypercalcemia, pathologic fracture, spinal cord compression, and radiotherapy to bone2. Several bisphosphonates have also demonstrated anticancer activity in preclinical models 3–8. A randomized controlled trial comparing conventional chemotherapy therapy alone with zoledronic acid 4 mg intravenously once every 28 days plus conventional chemotherapy in 94 previously untreated multiple myeloma patients reported a significant benefit on overall survival (os) with the addition of zoledronic acid9. However, until recently, randomized controlled trials of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma have otherwise failed to demonstrate improvements in progression-free survival (pfs) or os 2,10,11.

The U.K. Medical Research Council (mrc) Myeloma IX study (mmix) was a randomized placebo-controlled trial with a 2×2 factorial design and two randomization steps that allowed for a comparison of both first-line and maintenance treatments for adult patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. The design and results of the trial have been reported in detail elsewhere 12–16. The trial included adult patients with newly-diagnosed histologically-confirmed symptomatic multiple myeloma (International Staging System stage i, ii, or iii). The first randomization step compared first-line treatments for multiple myeloma either with zoledronic acid 4 mg every 3–4 weeks or with clodronate 1600 mg daily. The second randomization step compared maintenance treatment using 50 mg thalidomide daily (increasing to 100 mg daily if tolerated) with no further treatment.

Of 1970 patients randomized to treatment, 1960 were evaluable. Median follow-up in the initial analysis was 3.7 years. Approximately 75% of patients stayed on bisphosphonate therapy until disease progression. For patients who discontinued treatment, median time on treatment was 156 days for those receiving clodronate and 270 days for those receiving zoledronic acid. Median os was 5.5 months longer among patients receiving zoledronic acid [50.0 vs. 44.5 months with clodronate; hazard ratio (hr): 0.87; 95% confidence interval (ci): 0.77 to 0.99; p = 0.04], based on a log-rank test with stratification on the intensive compared with the non-intensive pathway. Based on a Cox model stratified by pathway and adjusted for minimization factors, zoledronic acid reduced the risk of death by 16% (hr: 0.842; 95% ci: 0.736 to 0.963; p = 0.04). Median pfs was 2.0 months longer among patients receiving zoledronic acid (19.5 months vs. 17.5 months with clodronate; hr: 0.91; 95% ci: 0.82 to 1.01; p = 0.07), and use of zoledronic acid reduced the risk of progression or death by 12% (hr: 0.88; 95% ci: 0.80 to 0.98; p = 0.0179). Compared with patients receiving clodronate, patients receiving zoledronic acid experienced fewer sres (27.0% vs. 35.3%; hr: 0.74; p = 0.0004).

Zoledronic acid and clodronate were both generally well tolerated. The incidence of confirmed osteonecrosis of the jaw (onj) was 3.6% with zoledronic acid and 0.3% with clodronate.

In their deliberations about pricing, reimbursement, and access to novel therapies, health care decision-making authorities in the United States, Canada, and other countries require information about cost-effectiveness. The objective of the present evaluation was to assess, from a Canadian health care system perspective, the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid compared with clodronate in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma.

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview

A partitioned survival analysis model was developed to estimate the expected lifetime outcomes and costs of treatment of multiple myeloma in patients receiving first-line treatment for newly-diagnosed stages i–iii multiple myeloma who were alternatively assumed to receive bisphosphonate therapy with zoledronic acid 4 mg every 3–4 weeks or clodronate 1600 mg daily. Clinical effectiveness (pfs, os, incidence of sres and adverse events) for zoledronic acid and clodronate were based on the results of the mmix trial. Other model parameters were based on data from secondary sources identified by a review of the literature. To the extent possible, the methods used in the evaluation are consistent with guidelines for the economic evaluation of oncology products from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (cadth)17.

The partitioned survival analysis model used in this study is similar to the q-twist approach, a well-established analytic framework for evaluating oncology therapies18, and also to the models used in numerous earlier economic assessments of treatments for advanced or metastatic cancers, including recent evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of bortezomib and lenalidomide for relapsed refractory multiple myeloma19 and of bortezomib and thalidomide for first-line treatment of multiple myeloma20. In this approach, survival is partitioned into three mutually exclusive health states:

Alive and not progressed

Alive and progressed

Dead

The proportion of patients in each health state, over the course of time, is estimated based on empirical or parametric survival functions (or both) for pfs and os. Post-progression survival was assumed to equal the difference between os and pfs. Expected pfs and expected os are calculated as the area under their respective survival curves. Expected post-progression survival is the area between the pfs and os curves. Costs and quality of life were assumed to be conditioned on treatment and expected time in the given disease states. This approach is similar to a traditional Markov model21, except that it does not require explicit calculation of transition probabilities between states.

Outcomes calculated by the model for each treatment included expected progression-free life-years, expected post-progression life-years, expected overall life-years, expected quality-adjusted life-years (qalys), and expected lifetime costs of multiple myeloma care. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (icer) was calculated as the ratio of the difference in expected lifetime cost of multiple myeloma care to the expected difference in qalys (“cost per qaly gained”) between zoledronic acid and clodronate. All outcomes were evaluated over a 20-year (240-month) timeframe, beginning with treatment start. This timeframe approximates a lifetime projection, consistent with cadth recommendations17. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of the Canadian publicly-funded health care system and is focused specifically on the costs of multiple myeloma–related care. Expected outcomes and costs were calculated on a discounted basis using an annual discount rate of 5%22. The model was programmed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, U.S.A.).

2.2. Model Estimation

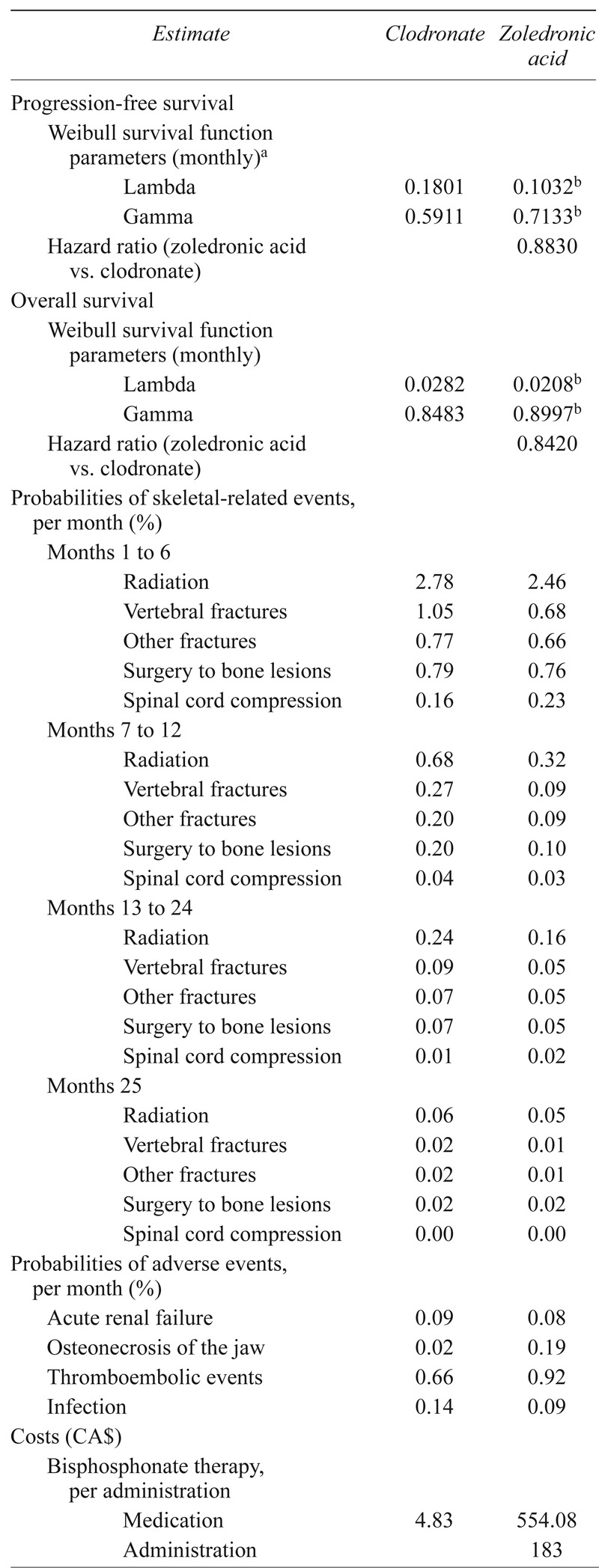

Parameters used in the model are reported in Table i and described below.

TABLE I.

Model parameters

| Estimate | Clodronate | Zoledronic acid |

|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival | ||

| Weibull survival function parameters (monthly)a | ||

| Lambda | 0.1801 | 0.1032b |

| Gamma | 0.5911 | 0.7133b |

| Hazard ratio (zoledronic acid vs. clodronate) | 0.8830 | |

| Overall survival | ||

| Weibull survival function parameters (monthly) | ||

| Lambda | 0.0282 | 0.0208b |

| Gamma | 0.8483 | 0.8997b |

| Hazard ratio (zoledronic acid vs. clodronate) | 0.8420 | |

| Probabilities of skeletal-related events, per month (%) | ||

| Months 1 to 6 | ||

| Radiation | 2.78 | 2.46 |

| Vertebral fractures | 1.05 | 0.68 |

| Other fractures | 0.77 | 0.66 |

| Surgery to bone lesions | 0.79 | 0.76 |

| Spinal cord compression | 0.16 | 0.23 |

| Months 7 to 12 | ||

| Radiation | 0.68 | 0.32 |

| Vertebral fractures | 0.27 | 0.09 |

| Other fractures | 0.20 | 0.09 |

| Surgery to bone lesions | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| Spinal cord compression | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Months 13 to 24 | ||

| Radiation | 0.24 | 0.16 |

| Vertebral fractures | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Other fractures | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Surgery to bone lesions | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Spinal cord compression | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Months 25 | ||

| Radiation | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Vertebral fractures | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Other fractures | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Surgery to bone lesions | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Spinal cord compression | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Probabilities of adverse events, per month (%) | ||

| Acute renal failure | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Osteonecrosis of the jaw | 0.02 | 0.19 |

| Thromboembolic events | 0.66 | 0.92 |

| Infection | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Costs (CA$) | ||

| Bisphosphonate therapy, per administration | ||

| Medication | 4.83 | 554.08 |

| Administration | 183 | |

| Thalidomide, per day of administration | 17.84 | 17.84 |

| Adverse events, per event | ||

| Acute renal failure | 11,096 | 11,096 |

| Osteonecrosis of the jaw | 16,628 | 16,628 |

| Thromboembolic events | 9,043 | 9,043 |

| Infection | 10,931 | 10,931 |

| Skeletal related events, per event | ||

| Radiation | 1,546 | 1,546 |

| Vertebral fractures | 286 | 286 |

| Other fractures | 9,567 | 9,567 |

| Surgery to bone lesions | 38,495 | 38,495 |

| Spinal cord compression | 4,150 | 4,150 |

| Utilities | ||

| Progression-free survival | ||

| Baseline | 0.485 | 0.485 |

| Increase, per month | ||

| Months 1–3 | 0.027 | 0.023 |

| Months 4–12 | 0.010 | 0.013 |

| Post-progression survival | 0.485 | 0.485 |

For use in extrapolation; based on final 30 months of Kaplan–Meier data.

For use in sensitivity analysis.

2.2.1. PFS and OS

At the time the analyses were conducted, the maximum reported follow-up in the mmix trial was 72 months for zoledronic acid and 70 months for clodronate16. Because Kaplan–Meier estimates of pfs and os were greater than zero when analyses of pfs and os were conducted, it was necessary to project pfs and os beyond the end of the trial to obtain lifetime projections. Consistent with cadth guidelines17, estimates of pfs and os for zoledronic acid and clodronate through 5 years (60 months) of follow-up were obtained from empirical survival distributions (that is, the Kaplan–Meier curves). Beyond 5 years, pfs and os for zoledronic acid and clodronate were based on extrapolation. The 5-year cut-off point for extrapolation was used because the failure times recorded after that point were small in number, and subsequent empirical survival probabilities were potentially imprecise.

In their guidelines for the economic evaluation of oncology products, cadth recommends consideration of three possible alternatives for extrapolation of benefits beyond the duration of follow-up from the clinical study17:

Decreasing treatment effect

Immediate loss of benefit

Maintenance of treatment effect

The cadth guidelines further state that option 1 is the most relevant for the base case in an economic evaluation. The guidance also states that if option 2 or 3 is chosen, “the clinical relevance must be justified.” To assess the most appropriate assumption for duration of benefit, annual probabilities of death for each treatment group and the annual hr for os for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate were derived from the Kaplan–Meier survival curves in the mmix trial as reported by Morgan et al.16. The annual probability of death associated with zoledronic acid and clodronate generally diminished over time, but remained less for zoledronic acid than for clodronate for more than 5 years. The annual hrs for os with zoledronic acid compared with clodronate were 0.87, 0.91, 0.97, 0.84, and 0.76 in years 1–5 respectively. These data thus support the assumption of lifetime maintenance of treatment effect. Nevertheless, for completeness, results assuming diminishing treatment effects over time also were generated.

Estimates of pfs and os for clodronate during the extrapolation period were based on Weibull survival functions fit to the empirical survival data over the first 5 years of follow-up in the trial. The Weibull is a flexible survival function that allows for increasing or decreasing risk of events over time and takes the general form

where S[t] is the probability of not having experienced the event (for example, progression or death) at time t23. Lambda (λ) is often called the “event rate parameter,” and gamma (γ), the “shape parameter.” For γ = 1.0, the hazard rate is constant over time and the inverse of λ is the mean failure time. For γ < 1, the hazard rate for the event is a decreasing function of time. For γ > 1, the hazard rate is an increasing function of time. Weibull survival functions were estimated by digitizing the reported Kaplan–Meier survival curves (that is, S[t] and t) and then fitting ordinary least-squares regressions with ln{−ln(S[t])} as the dependent variable and ln(t) as the independent variable. [Taking the log of the negative log of the Weibull function yields a linear function with intercept equal to ln(λ) and coefficient on ln(t) equal to γ.] To prevent survival probabilities close to 1.0 from overly influencing regression results for os, values for t < 6 months were omitted from the regression. To improve the fit for pfs, the model was fit only to the last 30 months of the survival distribution. Plots of ln{−ln(S[t])} compared with ln(t) for zoledronic acid and clodronate were approximately linear, which provided support for use of the Weibull model. The plots also were approximately parallel, which supports the assumption of proportionality of hazards (that is, no diminishment of benefit).

During the extrapolation period, pfs and os for zoledronic acid were obtained by applying the hrs for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate (hrZOLvsCLO) to the survival distributions for clodronate using the formula

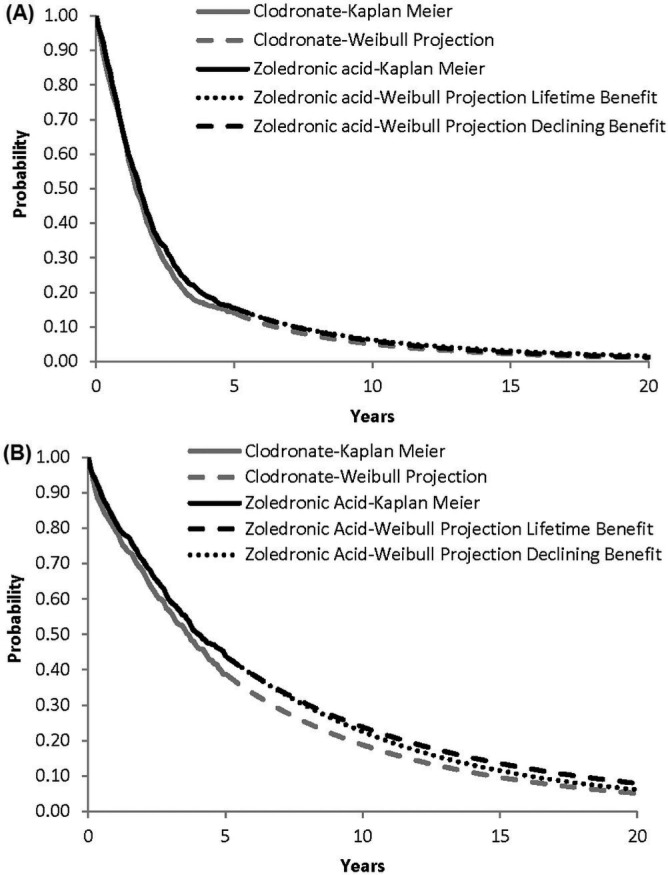

In the lifetime benefits scenario, the hrs for pfs and os for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate (0.883 and 0.842 respectively) were assumed to remain constant. In the diminishing benefits scenario, it was assumed that the hrs for pfs and os for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate would both increase linearly (from 0.883 and 0.842 respectively) to 1.0 over 5 years beginning at the first month of the extrapolation. Figure 1 shows empirical and fitted survival functions for pfs and os for zoledronic acid and clodronate. The estimated pfs for zoledronic acid is similar under the lifetime and diminishing benefits scenarios. For os, the survival curves for zoledronic acid and clodronate remain separated over the entire projection under the lifetime benefits scenario, but the curves meet at approximately 20 years in the diminishing benefits scenario.

FIGURE 1.

Estimated (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival for zoledronic acid and clodronate.

2.2.2. SREs

Estimates of the cumulative incidence of sres by type of sre for each treatment were obtained from the mmix trial13. Although bone lesions were included among the sres considered in the trial, they were not included in the model because the effects of such events on costs and qalys are unknown. To calculate monthly probabilities of individual sres over time, cumulative incidence estimates during 42 months for each sre (18.2%, 5.1%, 4.6%, 5.0%, and 1.3% for radiotherapy, vertebral fracture, other fracture, bone surgery, and spinal cord compression respectively for zoledronic acid, and 21.6%, 9.0%, 6.7%, 5.9%, and 1.9% respectively for clodronate) were partitioned into intervals based on the treatment-specific estimates of percentage of first sres occurring during months 1–6, 7–12, 13–24, and 24–42 of follow-up13. Treatment- and period-specific cumulative incidence estimates for each sre and treatment were then converted to monthly probabilities.

2.2.3. Adverse Events

Estimates of the incidence of adverse events for zoledronic acid and clodronate were obtained from the mmix trial16. Adverse events considered in the model included acute renal failure, onj, thromboembolic events, and infection. Those events were included either because their incidence was higher among patients receiving zoledronic acid or because the event is of particular concern for bisphosphonate therapy. Although the incidence of serious treatment-emergent musculoskeletal, connective tissue, and bone disorders was higher among zoledronic acid patients, the incidence of such events was low (<2%) and the typical treatments are generally limited (for example, acetaminophen). The effects of such events on costs and qalys are likely to be small, and those events were therefore not included in the analyses. Cumulative incidence estimates were converted to constant monthly probabilities, assuming that patients are at risk of adverse events until death.

2.2.4. Utilities

Utility values in the model were estimated based on self-reported eq-5d assessments collected in the mmix trial. The eq-5d is a brief, multi-attribute measure covering 5 domains of health-related quality of life, each with 3 levels, yielding 243 possible distinct health states, with utility values for each state obtained from community preference weights24. In the mmix trial, the eq-5d was administered before initial randomization (baseline), 3 months after initial randomization, and 3 months after maintenance randomization (if applicable). Of 1960 patients in the intention-to-treat population, 1551 patients (79%) had valid eq-5d assessments at baseline, 1440 (73%) had valid eq-5d assessments at 3 months after initial randomization, and 682 (35%) had valid assessments at 3 months after maintenance randomization. Mean eq-5d utility at baseline was 0.49 ± 0.38 for zoledronic acid and 0.48 ± 0.37 for clodronate. From baseline to 3 months after initial randomization, the mean utility value increased to 0.55 ± 0.30 in the zoledronic acid group and to 0.55 ± 0.30 in the clodronate group. At 3 months after maintenance randomization, the mean utility value increased to 0.66 ± 0.26 in the zoledronic acid group and to 0.67 ± 0.27 in the clodronate group.

In the model, utility values for pfs at time 0 were based on the mean utility value at baseline for the zoledronic acid and clodronate groups combined (0.485). Utility values during each month of the first year after treatment initiation were derived from the treatment group–specific increase in mean utility from baseline to 3 months after initial randomization and from 3 months after initial randomization to 3 months after maintenance randomization, assuming that the 3 months after maintenance randomization assessment occurred approximately 12 months after initial randomization, and that mean utility values increase linearly over time during each period. Because the eq-5d was not administered after progression in the mmix trial, health-related quality of life was assumed to return to baseline after progression for both treatment groups (that is, post-progression utility was assumed to be equal to 0.485). It was assumed that eq-5d assessments from the mrc myeloma trial captured the effects of sres and adverse events on health-related quality of life in the study patients.

2.2.5. Costs

The unit cost of clodronate was obtained from the Ontario Public Drug Program25. The unit cost of zoledronic acid was obtained from the ims–Brogan imam database26. The cost per administration of zoledronic acid was obtained from a study that used time and motion data collected from 6 patients being treated with zoledronic acid or pamidronate in 3 outpatient cancer clinics in the United States, combined with fixed, variable, and labour costs obtained from Canadian sources27. The cost per administration of clodronate was conservatively assumed to be $0. To estimate duration of treatment for zoledronic acid and clodronate, time to discontinuation was assumed to be distributed as a Weibull function with shape (γ) parameters the same as those for pfs, and a λ calculated to yield median times to discontinuation for zoledronic acid and clodronate reported in the mmix trial (approximately 12 months for both groups).

Costs of sres were obtained from a cost–utility analysis of pamidronate in patients with advanced breast cancer28. Costs of adverse events were based on hospitalization costs obtained from the Ontario Case Costing Initiative database29. All patients were assumed to receive thalidomide 150 mg daily as maintenance therapy. Time to discontinuation for thalidomide maintenance therapy was assumed to be distributed as a Weibull function with shape parameters equal to those for pfs and with λ calibrated to yield a median time to discontinuation of 7 months15. The cost of thalidomide therapy was estimated from the ims–Brogan imam database26. Costs of induction chemotherapy were not considered, because those costs are not likely to be affected by bisphosphonate therapy. Cost estimates were adjusted to 2010 Canadian dollars as necessary30.

2.3. Analyses

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted by simultaneously sampling from estimated probability distributions of model parameters to obtain 1000 sets of model input estimates31. When sampling the hrs for os and pfs of clodronate compared with zoledronic acid, treatment effects on pfs and os were assumed to be correlated, with a correlation coefficient equal to 0.79 from a study of the association between pfs and os in various metastatic cancers32. The cumulative incidences of adverse events and sres were assumed to be distributed as beta random variables. Other estimates were assumed to be distributed as either normal or lognormal random variables. If standard errors for model estimates were unavailable, they were assumed to be 25% of their base-case estimates. For each simulation, we calculated the differences between zoledronic acid and clodronate in costs and qalys. The 95% confidence intervals (cis) for incremental costs and qalys were calculated based on the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the simulations. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were calculated for zoledronic acid compared with no zoledronic acid33.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses were undertaken to explore the effect of zoledronic acid on the icer by changing assumptions concerning the values of key model parameters. Key model probabilities and costs were varied across their 95% cis (if available) or, otherwise, from 50% to 150% of base-case values. Cost-effectiveness was calculated using annual discount rates of 0% (that is, no discounting) and 3%. Several alternative approaches were used to project pfs and os for zoledronic acid beyond the end of the mmix trial. First, results were generated assuming immediate cessation of benefits for zoledronic acid after 5 years (that is, a hr equal to 1.0 for pfs and os for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate after 5 years). Results were also generated with the extrapolation beginning at median follow-up (3.7 years), alternatively assuming lifetime, diminishing, and immediate cessation of benefits. In addition, results were generated with pfs and os for zoledronic acid beyond 5 years estimated using independent Weibull functions fit to the Kaplan–Meier curves from the mmix trial (that is, assuming no proportionality of hazards).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Base-Case Results

Table ii presents the base-case results. Assuming lifetime benefit, life expectancy (undiscounted) was projected to be increased by 0.83 years (10.0 months) with zoledronic acid. The qalys gained with zoledronic acid compared with clodronate were 0.41. On a discounted basis, qalys gained were 0.27. Expected lifetime costs of bisphosphonate therapy (including administration and monitoring costs) were CA$13,445 greater with zoledronic acid. Expected costs of sres were reduced by CA$720 with zoledronic acid. Expected costs of adverse events were increased by CA$725 with zoledronic acid. Expected total lifetime costs were increased by CA$13,407 with zoledronic acid. The icer for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate was CA$49,829 per qaly gained. With a threshold of CAN$100,000 per qaly, the probability that zoledronic acid is cost-effective compared with clodronate was estimated to be 80% (Figure 2).

TABLE II.

Base-case results

| Outcome measure |

Zoledronic acid

|

Clodronate |

Zoledronic acid vs. clodronate

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime benefita | Declining benefitb | Lifetime benefita | Declining benefitb | ||

| Effectiveness | |||||

| Progression-free survival (years) | 2.94 | 2.89 | 2.65 | 0.29 | 0.24 |

| Progression-free survival, discounted (years) | 2.52 | 2.50 | 2.31 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| Time to discontinuation (years) | 1.56 | 1.55 | 1.60 | −0.04 | −0.05 |

| Time to discontinuation, discounted (years) | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.49 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| Post-progression survival (years) | 3.49 | 3.32 | 2.95 | 0.55 | 0.38 |

| Post-progression survival, discounted (years) | 2.50 | 2.41 | 2.17 | 0.34 | 0.25 |

| Life years | 6.43 | 6.21 | 5.60 | 0.83 | 0.61 |

| Life years, discounted | 5.03 | 4.91 | 4.48 | 0.55 | 0.43 |

| Quality-adjusted life years | 3.55 | 3.44 | 3.14 | 0.41 | 0.30 |

| Quality-adjusted life years, discounted | 2.80 | 2.74 | 2.53 | 0.27 | 0.21 |

| Expected lifetime costs (CA$) | |||||

| Bisphosphonates | 16,080 | 16,021 | 2,635 | 13,445 | 13,386 |

| Thalidomide maintenance therapy | 5,695 | 5,693 | 5,737 | −42 | −44 |

| Skeletal-related events | 4,152 | 4,152 | 4,872 | −720 | −720 |

| Adverse events | 6,625 | 6,475 | 5,900 | 725 | 574 |

| Total | 32,551 | 32,340 | 19,143 | 13,407 | 13,197 |

| Cost per quality-adjusted life year gained | 49,829 | 63,027 | |||

Progression-free survival and overall survival for zoledronic acid after 60 months are estimated by applying to projections for clodronate the estimated hazard ratios for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate from the U.K. Medical Research Council Myeloma ix trial.

Progression-free survival and overall survival for zoledronic acid after 60 months are estimated by applying to projections for clodronate the estimated hazard ratios for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate from the U.K. Medical Research Council Myeloma ix trial, assuming that the hazard ratio for zoledronic acid increases to 1.0 over 5 years beginning at the end of year 5.

FIGURE 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for zoledronic acid. Curves represent the proportion of simulations (n = 1000) for which the net health benefit for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate is greater than zero, given the threshold value for cost-effectiveness (λ) shown on horizontal axis. Net health benefit = Δ quality-adjusted life years (qalys) – Δ Costs / λ.

Assuming diminishing benefits, life expectancy (undiscounted) was projected to be increased by 0.61 years (7.4 months) with zoledronic acid. The qalys gained with zoledronic acid compared with clodronate were 0.30. On a discounted basis, total qalys gained were 0.21 (78% of the gain estimated for the lifetime benefit scenario). Expected lifetime costs of bisphosphonate therapy (including administration and monitoring costs) were CA$13,197 greater with zoledronic acid. Expected costs of sres were reduced by CA$720 with zoledronic acid. Expected costs of adverse events were increased by CA$574 with zoledronic acid. Expected total lifetime costs were increased by CA$13,197 with zoledronic acid. The icer for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate was CA$63,027 per qaly gained. With a threshold of CAN$100,000 per qaly, the probability that zoledronic acid is cost-effective compared with clodronate was estimated to be 67%.

3.2. Deterministic Sensitivity Analyses

Table iii presents results of the deterministic sensitivity analyses. In general, the results are relatively insensitive to the parameter changes reflected in the various scenarios. Assuming lifetime benefit, the estimated cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid compared with clodronate ranged from CA$32,726 per qaly gained (scenario 12: decrement in utility for pfs vs. perfect health, set to −50% of its base-case value) to CA$104,378 per qaly gained (scenario 13: decrement in utility with pfs vs. perfect health, set to +50% of its base-case value). Assuming diminishing benefits, cost-effectiveness ranged from CA$41,150 per qaly gained (scenario 12) to CA$134,566 per qaly gained (scenario 13).

TABLE III.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses

| Scenario |

Zoledronic acid (zol) vs. clodronate (clo)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lifetime benefita

|

Declining benefitb

|

||||||

| Costs (CA$) | qalys | icer (CA$) | Costs (CA$) | qalys | icer (CA$) | ||

| 1 | Base case | 13,407 | 0.27 | 49,829 | 13,197 | 0.21 | 63,027 |

| 2 | hr pfs zol vs. clo: 95% cil | 13,569 | 0.28 | 48,688 | 13,270 | 0.21 | 62,234 |

| 3 | hr pfs zol vs. clo: 95% ciu | 13,385 | 0.27 | 50,005 | 13,185 | 0.21 | 63,154 |

| 4 | hr os zol vs. clo: 95% cil | 13,531 | 0.31 | 43,040 | 13,241 | 0.23 | 58,684 |

| 5 | hr os zol vs. clo: 95% ciu | 13,293 | 0.23 | 58,546 | 13,153 | 0.19 | 67,983 |

| 6 | zol administration costs: −50% | 11,411 | 0.27 | 42,410 | 11,208 | 0.21 | 53,528 |

| 7 | zol administration costs: +50% | 15,404 | 0.27 | 57,247 | 15,185 | 0.21 | 72,526 |

| 8 | Adverse event costs: −50% | 13,045 | 0.27 | 48,482 | 12,909 | 0.21 | 61,655 |

| 9 | Adverse event costs: +50% | 13,770 | 0.27 | 51,175 | 13,484 | 0.21 | 64,399 |

| 10 | Skeletal-related event costs: −50% | 13,767 | 0.27 | 51,167 | 13,557 | 0.21 | 64,746 |

| 11 | Skeletal-related event costs: +50% | 13,047 | 0.27 | 48,491 | 12,837 | 0.21 | 61,308 |

| 12 | Disutility pfs vs. perfect health: −50% | 13,407 | 0.41 | 32,726 | 13,197 | 0.32 | 41,150 |

| 13 | Disutility pfs vs. perfect health: +50% | 13,407 | 0.13 | 104,378 | 13,197 | 0.10 | 134,566 |

| 14 | Disutility pps vs. baseline pfs after 1 year (average of zol and clo): −50% | 13,407 | 0.30 | 44,804 | 13,197 | 0.23 | 56,959 |

| 15 | Disutility pps vs. baseline pfs after 1 year (average of zol and clo): +50% | 13,407 | 0.24 | 56,123 | 13,197 | 0.19 | 70,543 |

| 16 | Cost of onj (CA$100,000; disutility with onj = 0.5) | 14,009 | 0.25 | 55,803 | 13,672 | 0.20 | 70,077 |

| 17 | Costs/outcomes not discounted | 14,612 | 0.41 | 35,218 | 14,214 | 0.30 | 47,465 |

| 18 | Costs/outcomes discounted at 3% | 13,834 | 0.32 | 43,674 | 13,564 | 0.24 | 56,609 |

| 19 | Begin extrapolation at median follow-up (3.7 years) | 13,463 | 0.27 | 49,070 | 13,152 | 0.19 | 69,074 |

Progression-free survival and overall survival for zoledronic acid after 60 months are estimated by applying to projections for clodronate the estimated hazard ratios for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate from the U.K. Medical Research Council Myeloma ix trial.

Progression-free survival and overall survival for zoledronic acid after 60 months are estimated by applying to projections for clodronate the estimated hazard ratios for zoledronic acid compared with clodronate from the U.K. Medical Research Council Myeloma ix trial, assuming that the hazard ratio for zoledronic acid increases to 1.0 over 5 years beginning at the end of year 5.

qaly = quality-adjusted life year; icer = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; hr = hazard ratio; pfs = progression-free survival; cil = lower bound of 95% confidence interval; ciu = upper bound of 95% confidence interval; os = overall survival; onj = osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Cost-effectiveness was CA$76,498 per qaly gained, assuming immediate loss of benefit after 5 years (that is, hrs for pfs and os were 1.0 after 5 years). If extrapolation of the survival curves begins at 3.7 years (median duration of follow-up in the initial analyses of the mmix trial) rather than at 5 years, cost-effectiveness is CA$49,070 per qaly under the lifetime benefits scenario and CA$69,074 under the diminishing benefits scenario. Beginning extrapolation at 3.7 years and assuming immediate loss of benefit at that point, cost-effectiveness was CA$94,109 per qaly gained. Cost-effectiveness was CA$78,064 per qaly gained if pfs and os for zoledronic acid after 5 years had been estimated based on independent Weibull distributions fit to the Kaplan–Meier curves for zoledronic acid (that is, rather than assuming proportional hazards compared with clodronate).

4. DISCUSSION

In Canada, there is no explicit threshold for determining whether an intervention is cost-effective34. In a recent study that reviewed published drug reimbursement recommendations for oncology products generated by the advisory board of the Common Drug Review (Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee) between September 2003 and March 2007, and in which cost-effectiveness was considered (25 files), there were 12 negative and 13 positive recommendations35. Medications with positive recommendations had cost-effectiveness ratios ranging from dominant to CA$80,000 per qaly gained. Medications with negative recommendations had cost-effectiveness ratios ranging from CA$32,000 to CA$137,000 per qaly gained. Those results suggest the lack of a hard and fixed threshold for determining cost-effectiveness. Nevertheless, the cost-effectiveness ratios for zoledronic acid estimated here under both the lifetime and the diminishing benefit scenarios (CA$49,829 and CA$63,027 per qaly gained respectively) are both below the maximum value for oncology medicines with positive recommendations.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First and foremost, the evaluation was based on assumptions regarding the treatment effects of zoledronic acid on os beyond the reported end of follow-up in the mmix trial. Since the analyses reported here were completed, updated analyses of the mmix trial, with a median follow-up of 6 years and a maximum reported follow-up for os of 8 years, have been reported36. The findings with respect to os from the updated analyses (hr: 0.88; 95% ci: 0.80 to 0.97; p = 0.03) are similar to those from the initial analyses (hr: 0.87; 95% ci: 0.77 to 0.99; p = 0.04), suggesting that the benefits of zoledronic acid on os were maintained with extended follow-up. Of particular note, the convergence of the os curves between 5 and 6 years observed in the original analyses were not observed in the updated analysis. Although those data provide additional support for the assumption that no diminishment of the treatment effects of zoledronic acid on os occurs over time, the true effects of zoledronic acid on os beyond the last reported follow-up from the mmix trial are unknown. Nevertheless, the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid was favourable (icer less than CA$100,000 per qaly) even when the benefits of zoledronic acid were conservatively assumed to persist for only 3.7 years (the median duration of follow-up in the original analysis of the mmix trial).

Second, data on the costs of sres and adverse events were not available from the trial and were obtained from secondary sources. We conservatively estimated the costs of adverse events based on hospitalization costs for similar diagnoses in the Ontario Case Costing Initiative database29. That approach may have overestimated the costs of adverse events, given that relatively few of the adverse events considered in the model were likely to have required hospitalization. For example, none of the cases of onj observed in the mmix trial required bone surgery. Also, although the incidence of thromboembolic events was higher among patients receiving zoledronic acid, the bulk of the imbalance in such events was the result of an increased number of events associated with the use of an indwelling catheter. Because use of such catheters is no longer standard practice, that observation may be of limited relevance to current practice. Although we assigned the cost of a hospitalization to all cases of acute renal failure, acute renal failure in the mmix trial was defined to include a variety of clinical parameters and was not limited to the need for dialysis. On the other hand, cost estimates from the Ontario Case Costing Initiative database do not include the costs of physician services, which may be substantial for adverse events that require surgery. However, as already noted, relatively few of the adverse events considered in the model were likely to have required hospitalization, and none of the cases of onj observed in the mmix trial required bone surgery. The values we used in the model are therefore likely to overestimate the costs of adverse events and, on balance, are therefore conservative. In any case, model results were relatively insensitive to the costs of those adverse events, so that any lack of precision in the cost estimates is not likely to have materially biased our findings one way or the other.

Based on results of the mmix trial, we assumed that utility values during pfs would be slightly lower for zoledronic acid than for clodronate after 6–12 months. Although mean utility values at 3 months after maintenance randomization were slightly lower for zoledronic acid than for clodronate, the difference (0.01) was not statistically significant or clinically meaningful37. Also, utility values at 3 months after maintenance randomization were based on a relatively small proportion of the overall population and may not be representative of quality of life in the overall study population. To the extent that patients with sres or adverse events were less likely to complete eq-5d assessments, the utility values we used might be biased by informative censoring. Analyses of utility data for patients with and without sres or adverse events (or both) were unavailable, and we were unable to assess the magnitude of any such bias or to correct for it. Because sres were more likely to occur in patients receiving clodronate, and because sres presumably have a negative impact on quality of life, any bias associated with informative censoring because of sres would favour clodronate. On the other hand, if patients with adverse events such as onj were more likely to have missing utility data, the bias might act in the other direction (in favour of zoledronic acid). The difference in the incidence of onj was relatively small compared with that for sres (4% with zoledronic acid vs. <1% with clodronate for onj compared with 27% with zoledronic acid vs. 35% with clodronate for sres), and most onj events were of low grade. It is therefore unlikely that informative censoring on utility data from sres or adverse events materially biased our utility estimates in favour of either therapy.

The mmix trial provided no information on utilities after progression. Utility after progression was therefore assumed to be the same as that at baseline (0.485). Although we lack data upon which to validate that estimate, it implies a decrement in utility from the maximum pre-progression values of 0.19 for clodronate and 0.17 for zoledronic acid (28% and 26% decrements respectively). Those decrements are similar to the assumed decrements in utilities associated with progression in other cost-effectiveness evaluations of myeloma therapy20. Data from numerous studies in patients with cancer suggest that many elements of quality of life remain stable but considerably impaired until the final few months of life, after which a sharp decline occurs in most domains38. Given that estimated post-progression survival was 2.95 years for clodronate and 3.49 years for zoledronic acid, an assumed post-progression utility value of 0.485 is not unreasonable.

The study by Dranitsaris and colleagues from which the cost of administration for zoledronic acid was obtained was based on just 3 patients27. However, the estimate of total administration time for zoledronic acid from the Dranitsaris study (66 minutes) is similar to that from a larger and more recent study of 39 patients by Richhariya and colleagues (69 minutes)39. The time-and-motion data from both studies came from the United States, but we know of no reason that those data might differ between the United States and Canada. Because unit costs for the study by Dranitsaris and colleagues were based on Canadian sources, we believe that the estimated cost of zoledronic acid administration used in the model is reasonable.

Our study did not examine the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid in comparison with other potential treatment strategies in patients with multiple myeloma. Although intravenous pamidronate is used as bisphosphonate therapy in many settings, controlled clinical trials of zoledronic acid compared with pamidronate or of clodronate compared with pamidronate in patients with multiple myeloma that report information on pfs and os are unavailable2. A comparison of the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid and clodronate with that of pamidronate in this indication therefore would require an adjusted indirect comparison using information from controlled trials of pamidronate compared with placebo10,11 and of clodronate compared with placebo40,41 in multiple myeloma patients. Such a comparison would represent a lower level of evidence than a comparison based on direct evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Similarly, we did not examine the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid compared with denosumab. Although zoledronic acid and denosumab were recently compared in a randomized controlled trial of patients with multiple myeloma and bone metastases of other advanced cancers (excluding breast and prostate cancer), detailed results for patients with multiple myeloma have not been reported42. Further research is therefore required to examine the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid compared with other bisphosphonates and with denosumab in this setting.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Compared with clodronate, zoledronic acid represents a cost-effective treatment alternative in patients with multiple myeloma.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Alex J. Szubert for his assistance in providing information from mmix trial.

An abstract that described preliminary results from this study was presented at the 2010 annual meeting of the American Society for Hematology. A manuscript describing an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid compared with clodronic acid for newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma from the U.K. health care system perspective based on a similar model to the one used in the present study was recently published in the Journal of Medical Economics (Delea TE, Rotter J, Taylor M, et al. J Med Econ 2012;15:454–64).

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Funding for this research was provided to Policy Analysis Inc. (pai) by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. TED and AW are employees of pai, which has received research funding and consulting fees from Novartis. JR was an employee of pai at the time this work was conducted. KEO is an employee of Novartis and owns stock or stock options in Novartis. SK is an employee of Celgene and was previously an employee of Novartis and owns stock or stock options in Novartis and Celgene. GJM has participated on advisory boards for, has received payment for lectures and development of educational presentations from, and has received travel support from Celgene, Novartis, Merck, and Johnson and Johnson.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mhaskar R, Redzepovic J, Wheatley K, et al. Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD003188. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003188.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corso A, Ferretti E, Lunghi M, et al. Zoledronic acid down-regulates adhesion molecules of bone marrow stromal cells in multiple myeloma: a possible mechanism for its antitumor effect. Cancer. 2005;104:118–25. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croucher PI, De Hendrik R, Perry MJ, et al. Zoledronic acid treatment of 5T2MM-bearing mice inhibits the development of myeloma bone disease: evidence for decreased osteolysis, tumor burden and angiogenesis, and increased survival. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:482–92. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Kaminski M, et al. Zoledronic acid versus pamidronate in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with breast cancer or osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma: a phase iii, double-blind, comparative trial. Cancer J. 2001;7:377–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scavelli C, Di Pietro G, Cirulli T, et al. Zoledronic acid affects over-angiogenic phenotype of endothelial cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3256–62. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shipman CM, Rogers MJ, Apperley JF, Russell RG, Croucher PI. Bisphosphonates induce apoptosis in human myeloma cell lines: a novel anti-tumour activity. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:665–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2713086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida R, Ashihara E, Sato K, et al. Gamma delta T cells kill myeloma cells by sensing mevalonate metabolites and icam-1 molecules on cell surface. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:613–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Castañeda C, Cleto S, Huerta–Guzmán J. Antitumour effect of zoledronic acid in previously untreated patients with multiple myeloma. Med Oncol. 2007;24:227–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02698044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Long-term pamidronate treatment of advanced multiple myeloma patients reduces skeletal events. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:593–602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:488–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602223340802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan G, Davies F, Gregory W, et al. Evaluating the effects of zoledronic acid (zol) on overall survival (os) in patients (Pts) with multiple myeloma (mm): results of the Medical Research Council (mrc) Myeloma IX study [abstract 8021] J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5474. [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=74&abstractID=54136; cited September 4, 2012] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan G, Davies FE, Gregory WM, et al. Zoledronic acid (zol) significantly reduces skeletal-related events (sres) versus clodronate (clo) in patients (Pts) with multiple myeloma (mm): results of the Medical Research Council (mrc) Myeloma IX study [abstract 1132O] Ann Oncol. 2010;21:viii350. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, et al. Optimising bone disease in myeloma; zoledronic acid plus thalidomide combinations improves survival and bone endpoints: results of the mrc Myeloma IX trial [abstract] Blood. 2010;116:311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-276386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, et al. Thalidomide maintenance significantly improves progression-free survival (pfs) and overall survival (os) of myeloma patients when effective relapse treatments are used: mrc Myeloma IX results [abstract] Blood. 2010;116:623. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, et al. First-line treatment with zoledronic acid as compared with clodronic acid in multiple myeloma (mrc Myeloma IX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1989–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62051-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittmann N, Evans WK, Rocchi A, et al. Addendum to CADTH’s Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Specific Guidance for Oncology Products. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Cole BF, Wieand HS, Schroeder G, Krook JE. A quality-adjusted time without symptoms or toxicity (q-twist) analysis of adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy for resectable rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1039–45. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.15.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornberger J, Rickert J, Dhawan R, Liwing J, Aschan J, Löthgren M. The cost-effectiveness of bortezomib in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Swedish perspective. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:484–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picot J, Cooper K, Bryant J, Clegg AJ. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bortezomib and thalidomide in combination regimens with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid for the first-line treatment of multiple myeloma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:1–204. doi: 10.3310/hta15410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 1993;13:322–38. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada. 3rd ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll KJ. On the use and utility of the Weibull model in the analysis of survival data. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:682–701. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(03)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickard AS, Wilke CT, Lin HW, Lloyd A. Health utilities using the eq-5d in studies of cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:365–84. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ontario Drug Benefit Program . Ontario Drug Benefit: Dispensing Fees. Toronto, ON: Ontario Public Drug Program; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.ims–Brogan. ims–Brogan imam database [electronic resource; updated September 7, 2010] Parsippany, NJ: Brogan, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dranitsaris G, Castel LD, Baladi JF, Schulman KA. Zoledronic acid versus pamidronate as palliative therapy in cancer patients: a Canadian time and motion analysis. J Oncol Pharmacy Pract. 2001;7:27–33. doi: 10.1191/1078155201jp077oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dranitsaris G, Hsu T. Cost utility analysis of prophylactic pamidronate for the prevention of skeletal related events in patients with advanced breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:271–9. doi: 10.1007/s005200050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Case Costing Initiative database [electronic resource] Toronto, ON: Ontario Case Costing Initiative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statistics Canada . Consumer Price Index, Historical Summary. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briggs A. Probabilistic analysis of cost-effectiveness models: statistical representation of parameter uncertainty. Value Health. 2005;8:1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.08101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkerson J, Fojo T. Progression-free survival is simply a measure of a drug’s effect while administered and is not a surrogate for overall survival. Cancer J. 2009;15:379–85. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181bef8cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Löthgren M, Zethraeus N. Definition, interpretation and calculation of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Econ. 2000;9:623–30. doi: 10.1002/1099-1050(200010)9:7<623::AID-HEC539>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleemput I, Neyt M, Thiry N, De Laet C, Leys M. Using threshold values for cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained in healthcare decisions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:71–6. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310001194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocchi A, Menon D, Verma S, Miller E. The role of economic evidence in Canadian oncology reimbursement decision-making: to lambda and beyond. Value Health. 2008;11:771–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, et al. mrc Myeloma IX, 6 year median follow-up (fu) highlights the importance of long-term fu in myeloma clinical trials and differential effects of thalidomide in high- and low-risk disease [abstract] Blood. 2011;118:993. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in eq-5d utility and vas scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giesinger JM, Wintner LM, Oberguggenberger AS, et al. Quality of life trajectory in patients with advanced cancer during the last year of life. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:904–12. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richhariya A, Qian Y, Zhao Y, Chung K. Time associated with intravenous zoledronic acid administration in patients with breast or prostate cancer and bone metastasis. Cancer Manag Res. 2012;4:55–60. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S27693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCloskey EV, Dunn JA, Kanis JA, MacLennan IC, Drayson MT. Long-term follow-up of a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:1035–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCloskey EV, MacLennan IC, Drayson MT, Chapman C, Dunn J, Kanis JA. A randomized trial of the effect of clodronate on skeletal morbidity in multiple myeloma. mrc Working Party on Leukaemia in Adults. Br J Haematol. 1998;100:317–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henry DH, Costa L, Goldwasser F, et al. Randomized, double-blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1125–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]