Abstract

Objective

This systematic review set out to summarize the research literature describing integrative oncology programs.

Methods

Searches were conducted of 9 electronic databases, relevant journals (hand searched), and conference abstracts, and experts were contacted. Two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts for reports describing examples of programs that combine complementary and conventional cancer care. English-, French-, and German-language articles were included, with no date restriction.

From the articles located, descriptive data were extracted according to 6 concepts: description of article, description of clinic, components of care, administrative structure, process of care, and measurable outcomes used.

Results

Of the 29 programs included, most were situated in the United States (n = 12, 41%) and England (n = 10, 34%). More than half (n = 16, 55%) operate within a hospital, and 7 (24%) are community-based. Clients come through patient self-referral (n = 15, 52%) and by referral from conventional health care providers (n = 9, 31%) and from cancer agencies (n = 7, 24%). In 12 programs (41%), conventional care is provided onsite; 7 programs (24%) collaborate with conventional centres to provide integrative care. Programs are supported financially through donations (n = 10, 34%), cancer agencies or hospitals (n = 7, 24%), private foundations (n = 6, 21%), and public funds (n = 3, 10%). Nearly two thirds of the programs maintain a research (n = 18, 62%) or evaluation (n = 15, 52%) program.

Conclusions

The research literature documents a growing number of integrative oncology programs. These programs share a common vision to provide whole-person, patient-centred care, but each program is unique in terms of its structure and operational model.

Keywords: Complementary medicine, cancer, oncology, integrative oncology, integrative medicine, systematic review, health systems

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer patients worldwide are increasingly combining complementary health care interventions such as acupuncture, massage therapy, and naturopathic medicine with conventional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. Population-based studies suggest that at least half of all cancer patients use some type of complementary therapy during their experience with cancer1–5. In parallel with and as a response to that trend, the field of integrative oncology has emerged to ensure that patients have access to evidence-based cancer care that is safe, comprehensive, and patient-centred throughout the cancer spectrum.

The goals of integrative oncology are to reduce the side effects of conventional treatment, to improve cancer symptoms, to enhance emotional health, to improve quality of life, and sometimes to enhance the effect of conventional treatments6–8. Sagar and Leis describe integrative oncology as both a science and a philosophy that recognizes the complexity of care for cancer patients and that provides a multitude of evidence-based approaches to accompany conventional therapies and to facilitate health9.

In 2009, the Society for Integrative Oncology published practice guidelines, representing evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of common problems encountered by cancer patients6. The guidelines are based on a summary and critical analysis of manuscripts and textbook chapters on complementary and integrative medicine in oncology and have proved useful for health professionals in providing evidence-based and patient-centred advice to individual patients. Practice guidelines are, however, only one part of integrative oncology practice. Integrative practice also requires that a number of interdisciplinary professionals practice alongside each other and, ideally, communicate in nonhierarchical and respectful ways to further the goals of treating the whole person and of promoting health10. This description of integrative practice is an idealized one, and it is more likely that practice models evolve with integration as a goal that is not necessarily achieved. Although it seems reasonable to expect that all integrative oncology practitioners share a common philosophy of patient-centred, whole-person, and evidence-based care, it is unclear how such a philosophy has developed within real-world examples of integrative oncology programs. The literature contains many reports that document examples of integrative oncology practice, and yet that literature has not been reviewed and summarized.

In the same way that practice guidelines have helped to advance the practice of integrative oncology, a summary of the literature describing integrative oncology programs is needed to inform the development of integrative oncology policies, to further develop and refine existing and new programs of care, and to begin conceptualizing the broader infrastructure of integrative oncology practice, education, and research.

Our objective was to use the methods of systematic review to summarize the research literature describing integrative oncology programs. Specifically, we were interested in summarizing elements relevant to the development and operation of an integrative oncology program or centre, including the components of care, administrative structure, process of care, and measurable outcomes used.

2. METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of the literature describing integrative oncology programs and centres. We expected a wide range of practice models11, and we therefore did not impose a strict definition of integrative health care. Instead, we searched for articles that described examples of integrative oncology care, based on the provision of complementary care in addition to (and not in opposition to) conventional care. Despite setting broad inclusion criteria for integrative oncology programs, we were careful to distinguish between “complementary” and “alternative” care, reviewing only program descriptions that include complementary therapies in addition to “conventional” care provided by medical doctors, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. Complementary therapies represent a diverse set of therapies that are nonsurgical and non-pharmaceutical, but that have known efficacy6. Alternative therapies do not have a scientific foundation and are typically promoted as alternatives to conventional care. Given the requirement for evidence within integrative oncology6,9, programs that provide alternative care were excluded from our review.

The search incorporated a number of methods to identify published articles. We searched the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Cochrane Library, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, embase, healthstar, medline, premedline, psycinfo, and csa Sociological Abstracts from inception through March 2010. The search strategy for medline appears in Appendix A. We hand-searched eight journals from their inception through December 2010 [Complementary Therapies in Medicine, Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, Current Oncology, Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice (formerly Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery), Alternative Medicine Review, Alternative and Complementary Therapies, Integrative Cancer Therapies, and Journal for the Society of Integrative Oncology] and hand-searched published abstracts from four complementary and integrative medicine conferences (Society for Integrative Oncology, North American Research Conference on Complementary and Integrative Medicine, International Congress on Complementary Medicine Research, and Canadian Interdisciplinary Network for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research). We also sent e-mail messages to 45 experts in integrative oncology, including authors of identified articles, to identify further potentially relevant articles.

Two investigators independently screened all identified titles and abstracts for potential inclusion in the review. Full-text reports of the selected records from the screening phase were obtained and a final assessment for inclusion was made independently by the same two reviewers. To be included, articles had to describe examples of clinics or programs that provide some combination of complementary and conventional cancer care exclusively to any one or a combination of cancer patients, cancer survivors, or people wishing to prevent cancer. Articles documenting general integrative medicine programs, even if cancer patients made up a substantial portion of the client base, and programs that provide only single-agent complementary therapies were excluded. Further, articles had to document original research or describe the process of cancer care. Abstracts for which we could not locate a full-text article were excluded, as were publications in a language other than English, French, or German. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data were extracted according to 6 main concepts and within 88 data elements guided by the key concepts of integrative health care practice as identified and described by Boon et al.10. The main concepts and data elements included

description of the article (for example, author, year of publication, article type);

description of the program (for example, name of clinic or program, setting of care, physical characteristics of a centre);

components of care (for example, conventional therapies offered, complementary therapies offered, means for practitioner collaboration);

administrative structure (for example, charitable status, hospital affiliation, means of cost recovery, process to develop program);

process of care (for example, process of initial assessment, process of referral between practitioners, involvement of family members and caregivers); and

measurable outcomes used (for example, active research or evaluation programs, or both).

A standardized data extraction form and guidelines were developed and pilot-tested to enhance reliability in data extraction. All data were extracted by one, and verified by a second, investigator. We contacted authors of the included articles to review key elements of the extracted data related to their programs and to supply any missing data. Data were summarized descriptively, using frequencies for categorical data and content analysis for qualitative data12, to generate a list of common categories.

This study was funded by the Lotte and John Hecht Memorial Foundation. The funder had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data and has no right to approve or disapprove publication of a finished manuscript. Because this study did not involve human participants, ethics approval was not required.

3. RESULTS

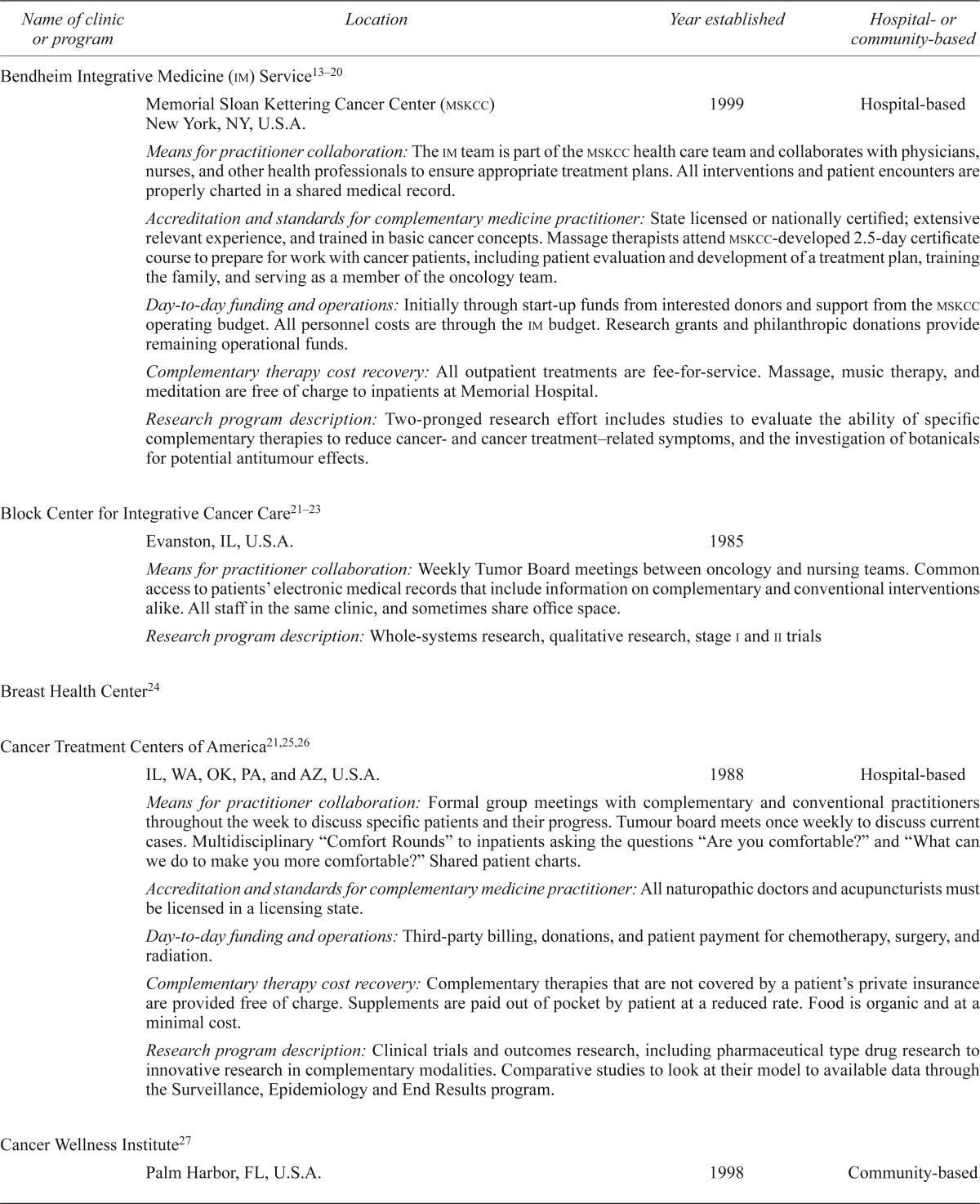

We identified 1622 records for screening, and we reviewed 220 full-text manuscripts for potential inclusion. In total, 53 articles describing 29 examples of integrative oncology programs were included in the review (Figure 1). As part of the identification of eligible programs, we sent e-mail messages to 24 individuals affiliated with the programs or centres included in our review for whom we could locate contact information. We asked those individuals to verify the extracted data and to provide missing data. Messages to 5 recipients were undeliverable, and the 19 remaining messages attracted 11 responses. As a result of this process, two programs were excluded as they were clarified to be integrative medicine and not specifically integrative oncology programs.

FIGURE 1.

prisma diagram of article flow throughout the systematic review

3.1. Description of Articles

The 53 included articles were published in journals or books specific to complementary therapies (n = 15, 28%), mainstream oncology (n = 15, 28%), integrative oncology (n = 12, 23%), conventional medicine (n = 8, 15%), social sciences (n = 2, 4%), and integrative medicine (n = 1, 2%). Almost half (n = 24, 45%) had been published in the last 5 years, and 46 (87%) had been published since the year 2000. Most articles (n = 44, 83%) were descriptive. A smaller number (17%) described research, including evaluation (n = 5, 55%), qualitative (n = 3, 33%), and observational (n = 2, 22%) studies.

3.2. Description of Integrative Oncology Programs

Of the 29 integrative oncology programs included in the review, 12 (41%) operate within the United States, 10 (34%) in England, 3 (10%) in Canada, and 2 (7%) in Germany [location not reported (nr) = 2 (7%)]. The described programs were established between 1968 and 2007, with 10 (34%) having been established in the 1990s, 6 (21%) in the 1980s, and 3 (10%) in the 2000s (establishment period nr = 9, 31%). At least 1 program ceased operation after publication: The Geffen Cancer Center and Research Institute closed in 2003, although it continued in a different format as the Seven Levels of Healing program. All but 2 programs operate in urban centres (locale nr = 5, 17%). More than half (n = 17, 59%) operate within a hospital setting; 7 (24%) are community-based; and 1 operates both within the community and within a U.S. National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (setting nr = 5, 17%).

In 14 programs (48%), treatment is offered to people with any type and any stage of cancer; 2 programs (7%) focus solely on breast cancer (clientele type nr = 13, 45%). Patient access to the programs most commonly comes from self-referral by patients (n = 16, 55%); referrals from conventional health care providers (n = 11, 38%), word of mouth (n = 10, 34%), advertising (n = 8, 28%), and referrals from a cancer agency (n = 8, 28%) also account for access. Few data about the physical characteristics of most centres were reported (physical characteristics nr = 20, 69%), but among the 9 programs that reported some aspect of their physical space, that space was most commonly described using such words as “peaceful,” “soothing,” and “natural.” Some features described included natural elements of wood and water, natural lighting, flowers and gardens, or aromatherapy and relaxing music.

3.3. Components of Care

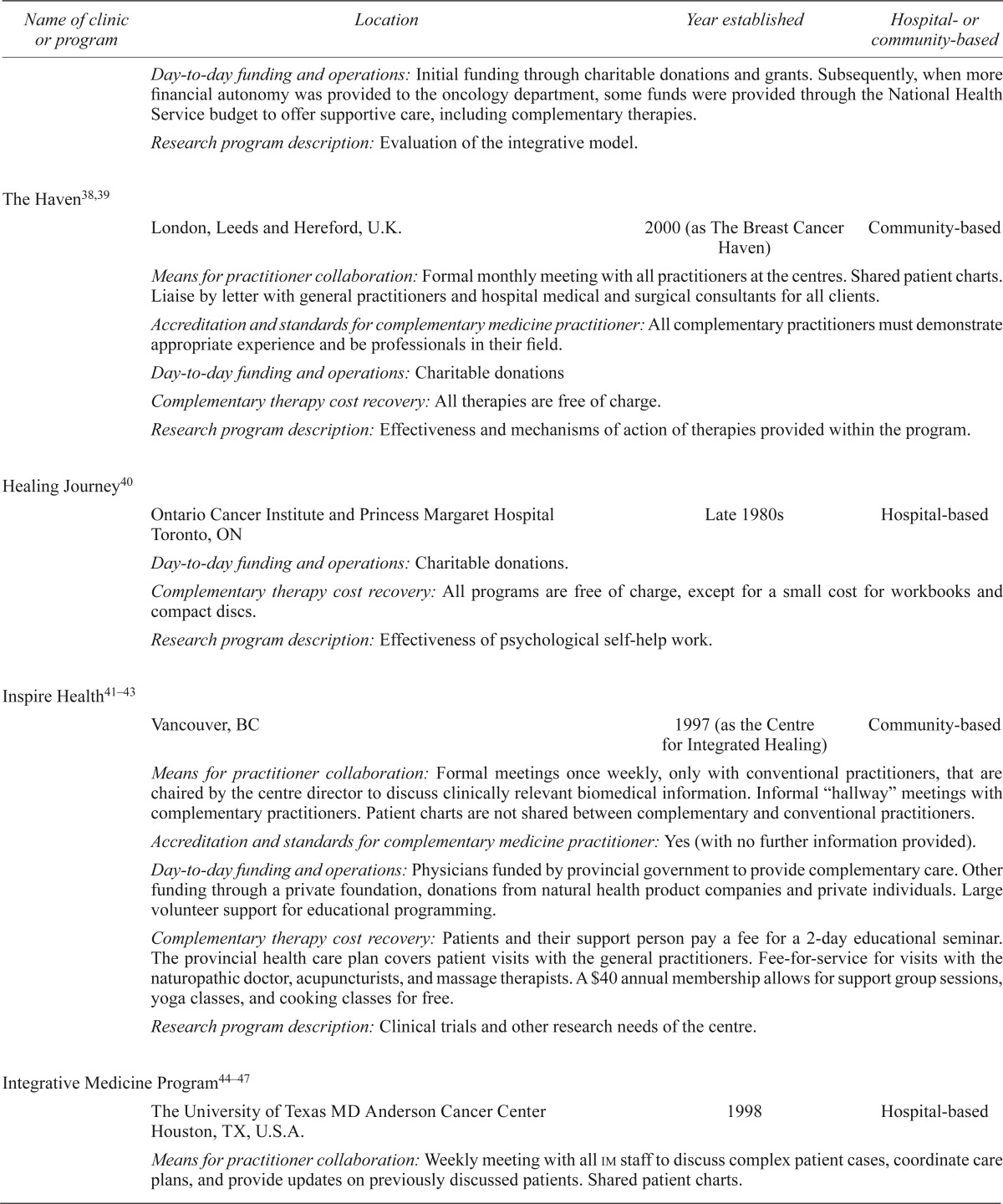

Fewer than half the programs (n = 12, 41%) provide both complementary and conventional therapies in the same location. Of the remaining programs, 8 (28%) provide complementary therapies at one location and collaborate with conventional oncology centres in other settings to provide an integrative approach to care (therapy locations nr = 9, 31%). Each program incorporates a number of complementary therapies, with mind–body medicine (including meditation, visualization, and relaxation), massage, nutrition counselling, and acupuncture being the most common (Figure 2). The decision to offer specific complementary therapies is most commonly made based on evidence (n = 12, 41%) and patient demand (n = 10, 34%). Other reasons include clinical experience (n = 3, 10%), recommendation from a conventional health care practitioner (n = 2, 7%), recommendation from a complementary health care practitioner (n = 1, 3%), availability of practitioners (n = 1, 3%), and the ability to easily integrate a therapy into a hospital setting (n = 1, 3%). The stated goals of all the included integrative oncology programs were closely aligned, collectively identifying common principles within the field, such as “whole-person,” “patient-centred,” “collaborative,” “empowerment,” and “evidence-based.” Further, each of the included programs had framed their goals in terms of providing high-quality supportive care alongside, and not in place of, conventional care.

Figure 2.

Complementary therapies offered within integrative oncology programs. Other therapies offered within 2 or fewer programs, and not represented in this figure, include dance therapy, herbal medicine, integrative medicine consultations, life coaching, relationship counselling, naturopathic medicine, Pilates, biofeedback, sound therapy, machine therapy, chiropractic, electrochemical therapies, enemas, healing garden, hyperthermia, orthobionomy, physiotherapy, quartz crystal bowls, Tibetan bowls, special baths, and Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Of the included programs, 12 (41%) reported that practitioners regularly meet in a formal setting; 5 (17%) reported not meeting formally; and 12 (41%) did not report on this topic. Of the 12 programs that reported regular meetings, those meetings occur at least weekly to discuss individual or complex cases, to develop and coordinate integrative care plans, or to provide updates on patients previously discussed. In 9 of the 12 programs, complementary and conventional care providers both attend the meetings; in 3 programs, only the conventional practitioners attend.

About half the programs (n = 16, 55%) reported involving family members or caregivers in their integrative program; the remaining 13 programs (45%) reported no data for such involvement. Most programs that involve family members and caregivers offer a package of care to those individuals that is the same as the package offered to patients (n = 8, 28%); others offer support sessions and psychological interventions (n = 3, 10%) or a more limited set of therapies (n = 3, 10%).

Education is often seen as an important component of integrative care, with more than half the programs (n = 16, 55%) reporting that they offer some element of community outreach or education, most commonly seminars or lectures (n = 9, 31%) or curriculum for health professionals (n = 3, 10%). One program described taking advantage of new media technologies, regularly developing and posting blogs and other multimedia entries on their Web site.

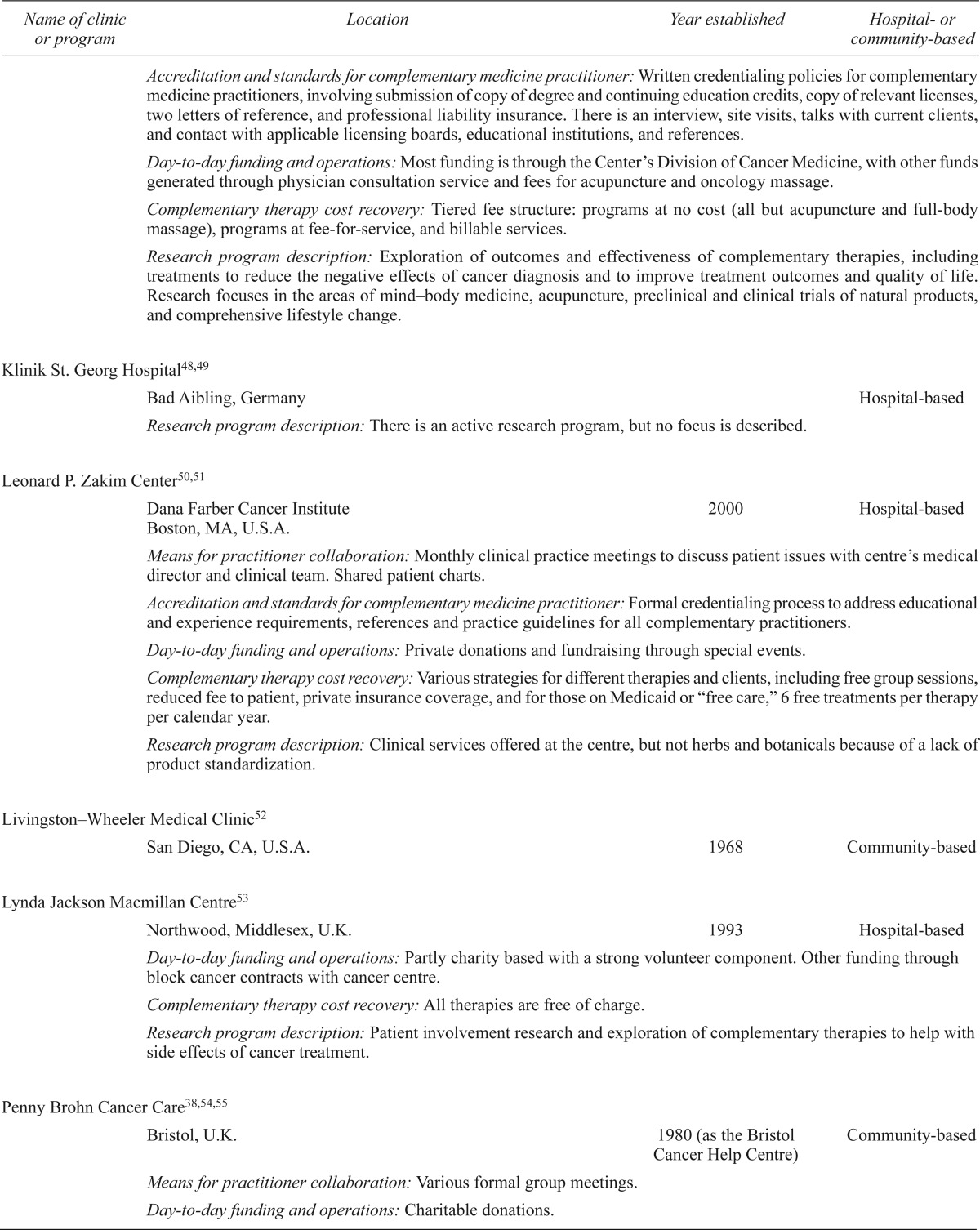

In general, few data about the components of integrative care were reported (Figure 3), including whether a primary caregiver is assigned to each patient (nr = 17, 59%), whether patient charts are shared between members of the integrative care team (nr = 16, 55%), and whether practitioners are required to hold certain credentials or to meet certain standards (nr = 18, 62%) or to undergo training specific to cancer (nr = 12, 41%).

Figure 3.

Components of care and organizational structure within integrative oncology programs. nr = not reported.

3.4. Administrative Structure

Although information was scarcely reported for many data elements related to the organizational structure of integrative oncology programs (Figure 3), some elements were fairly well reported. For example, almost two thirds of the programs (n = 18, 62%) reported having dedicated staff, but little information was reported about the number of full- and part-time staff, job titles, and responsibilities. It is also clear that approaching two thirds of the programs (n = 17, 59%) maintained a hospital affiliation, with those programs operating within or beside hospitals or cancer centres, or serving as a community affiliate of a local hospital.

About half the programs (n = 15, 52%) reported some information about the process they followed to develop their organizational structure (process nr = 14, 48%). Strategies varied and seemed to depend on the local environment in which the program would operate and also on the people who were leading the process. Most commonly, a steering committee or subcommittees (or both) were developed to explore issues such as staffing, funding, practice scope, and credentials (n = 5, 17%). Pilot studies and needs assessments were likewise common (n = 5, 17%). Other strategies included consultations with health care professionals, cancer patients, and administrative personnel (n = 3, 10%); offers of complementary or integrative medicine education to health care professionals and cancer patients (n = 3, 10%); and coordinated visits to established integrative oncology programs (n = 1, 3%).

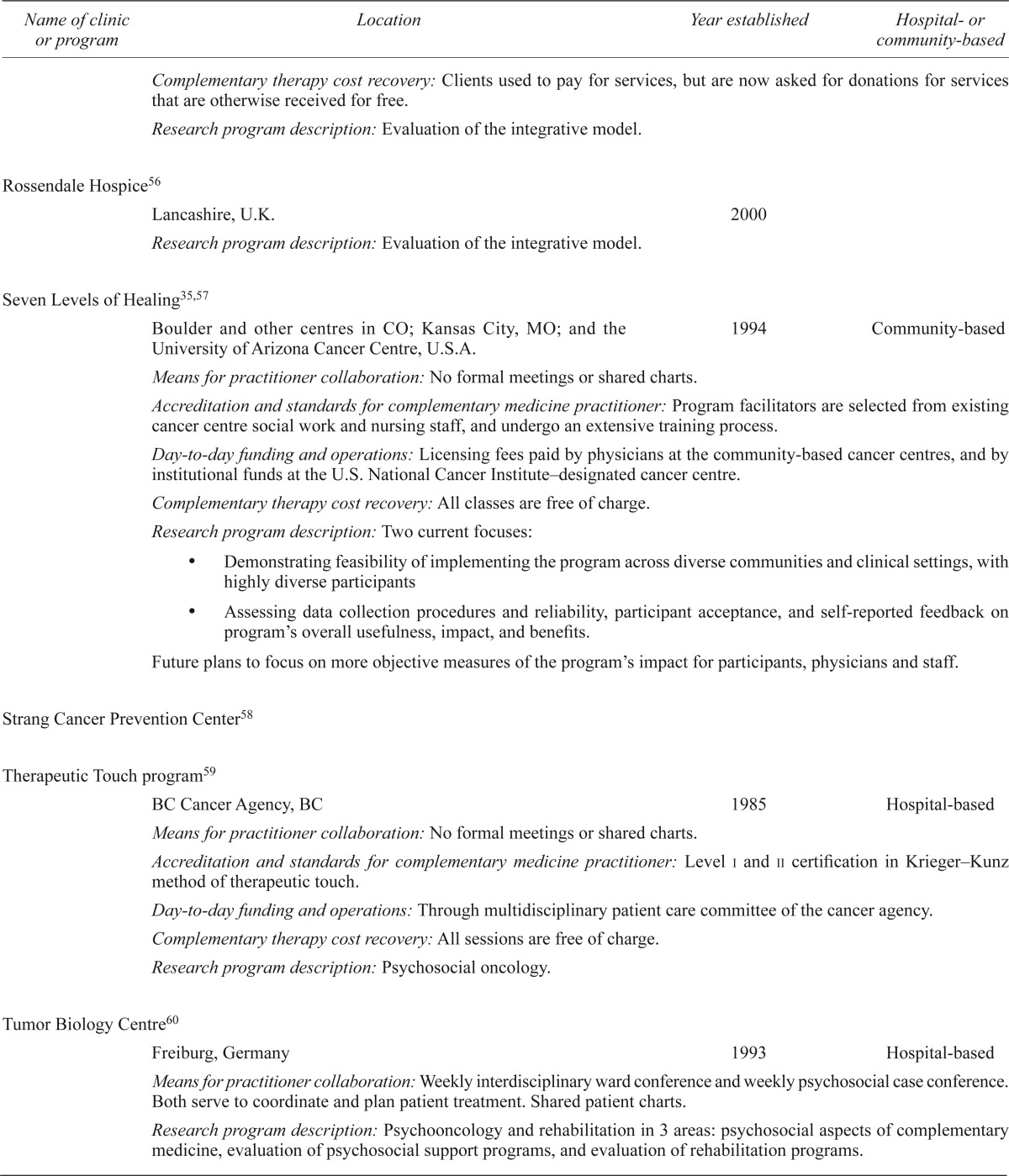

Many strategies were reported for funding daily operations and for recovering the costs of complementary (and, in some countries, conventional) cancer therapies from patients (Table i). Most programs described more than one funding and cost-recovery strategy. Daily operations are funded (funding nr = 10, 34%) through a combination of charitable donations (n = 13, 45%), cancer agency or hospital funds (n = 6, 21%), private foundation support (n = 5, 17%), public funding (n = 4, 14%), volunteer support (n = 2, 7%), licensing fees (n = 1, 3%), and research grants (n = 1, 3%). Costs of treatment are recovered (recovery nr = 13, 45%) through direct patient payment (n = 5, 17%), private insurance (n = 3, 10%), a membership fee (n = 1, 3%), and public health care (n = 1, 3%). At least some complementary therapies are offered free of charge within 15 programs (52%).

TABLE I.

Description of organizational structure and operations for integrative oncology programs

| Name of clinic or program | Location | Year established | Hospital- or community-based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bendheim Integrative Medicine (im) Service13–20 | |||

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (mskcc) New York, NY, U.S.A. |

1999 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: The im team is part of the mskcc health care team and collaborates with physicians, nurses, and other health professionals to ensure appropriate treatment plans. All interventions and patient encounters are properly charted in a shared medical record. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: State licensed or nationally certified; extensive relevant experience, and trained in basic cancer concepts. Massage therapists attend mskcc-developed 2.5-day certificate course to prepare for work with cancer patients, including patient evaluation and development of a treatment plan, training the family, and serving as a member of the oncology team. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Initially through start-up funds from interested donors and support from the mskcc operating budget. All personnel costs are through the im budget. Research grants and philanthropic donations provide remaining operational funds. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All outpatient treatments are fee-for-service. Massage, music therapy, and meditation are free of charge to inpatients at Memorial Hospital. | |||

| Research program description: Two-pronged research effort includes studies to evaluate the ability of specific complementary therapies to reduce cancer- and cancer treatment–related symptoms, and the investigation of botanicals for potential antitumour effects. | |||

| Block Center for Integrative Cancer Care21–23 | |||

| Evanston, IL, U.S.A. | 1985 | ||

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Weekly Tumor Board meetings between oncology and nursing teams. Common access to patients’ electronic medical records that include information on complementary and conventional interventions alike. All staff in the same clinic, and sometimes share office space. | |||

| Research program description: Whole-systems research, qualitative research, stage i and ii trials | |||

| Breast Health Center24 | |||

| Cancer Treatment Centers of America21,25,26 | |||

| IL, WA, OK, PA, and AZ, U.S.A. | 1988 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Formal group meetings with complementary and conventional practitioners throughout the week to discuss specific patients and their progress. Tumour board meets once weekly to discuss current cases. Multidisciplinary “Comfort Rounds” to inpatients asking the questions “Are you comfortable?” and “What can we do to make you more comfortable?” Shared patient charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: All naturopathic doctors and acupuncturists must be licensed in a licensing state. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Third-party billing, donations, and patient payment for chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Complementary therapies that are not covered by a patient’s private insurance are provided free of charge. Supplements are paid out of pocket by patient at a reduced rate. Food is organic and at a minimal cost. | |||

| Research program description: Clinical trials and outcomes research, including pharmaceutical type drug research to innovative research in complementary modalities. Comparative studies to look at their model to available data through the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program. | |||

| Cancer Wellness Institute27 | |||

| Palm Harbor, FL, U.S.A. | 1998 | Community-based | |

| Cavendish Centre for Cancer Care28,29 | |||

| Sheffield, U.K. | 1992 | ||

| Means for practitioner collaboration: With patient permission, assessors write to relevant health professionals to inform them of the centre’s intervention and its objective and again at review to inform them of outcomes. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All therapies are free of charge. | |||

| Research program description: Evaluation of the integrative model. | |||

| Complementary Therapies Program30 | |||

| St. Vincent’s Comprehensive Cancer Center New York, NY, U.S.A. |

Hospital-based | ||

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Formal weekly multidisciplinary meetings to discuss cases and identify patients who require follow-up. Other communication in person or by telephone as needed. A nurse specialist communicates relevant information between conventional and complementary practitioners as needed. Shared patient charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: All practitioners must have a state license. For those with no licensing board, program administrators interview practitioners and perform a site visit to ensure competency on a set of standard criteria and review reference letters. | |||

| Completing the Circle31,32 | |||

| Christie Hospital NHS Trust Manchester, U.K. |

1998 | Hospital-based | |

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Various mechanisms, including some hospital funding, external grants, and provision of income-generating educational courses. | |||

| Research program description: Evaluating treatments available within the program. | |||

| Edgewater Medical Center33 | |||

| Chicago, IL, U.S.A. | Hospital-based | ||

| Geffen Cancer Center and Research Institute34,35 | |||

| Vero Beach, FL, U.S.A. | 1994 (closed in 2003) | Community-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Formal daily meetings with medical oncologists and senior nursing and chemotherapy staff. Shared patient charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: All complementary practitioners were licensed in their respective fields and trained in conscious communication, team-building skills, and compassionate care for patients and loved ones. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Fee for service | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: Clinical drug trials and exploration of protein biomarkers for various types of cancer. | |||

| Hammersmith-Bristol Programme36,37 | |||

| London, U.K. | 1989 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Weekly team meetings to discuss individual patients, and twice-monthly planning meetings to develop new strategies and solve logistics problems. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: A standard for massage therapists (and potentially others) to ensure training to International Therapy Examination Council level or equivalent, plus 2 years of post-registration experience. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Initial funding through charitable donations and grants. Subsequently, when more financial autonomy was provided to the oncology department, some funds were provided through the National Health Service budget to offer supportive care, including complementary therapies. | |||

| Research program description: Evaluation of the integrative model. | |||

| The Haven38,39 | |||

| London, Leeds and Hereford, U.K. | 2000 (as The Breast Cancer Haven) | Community-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Formal monthly meeting with all practitioners at the centres. Shared patient charts. Liaise by letter with general practitioners and hospital medical and surgical consultants for all clients. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: All complementary practitioners must demonstrate appropriate experience and be professionals in their field. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All therapies are free of charge. | |||

| Research program description: Effectiveness and mechanisms of action of therapies provided within the program. | |||

| Healing Journey40 | |||

| Ontario Cancer Institute and Princess Margaret Hospital Toronto, ON |

Late 1980s | Hospital-based | |

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All programs are free of charge, except for a small cost for workbooks and compact discs. | |||

| Research program description: Effectiveness of psychological self-help work. | |||

| Inspire Health41–43 | |||

| Vancouver, BC | 1997 (as the Centre for Integrated Healing) | Community-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Formal meetings once weekly, only with conventional practitioners, that are chaired by the centre director to discuss clinically relevant biomedical information. Informal “hallway” meetings with complementary practitioners. Patient charts are not shared between complementary and conventional practitioners. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: Yes (with no further information provided). | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Physicians funded by provincial government to provide complementary care. Other funding through a private foundation, donations from natural health product companies and private individuals. Large volunteer support for educational programming. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Patients and their support person pay a fee for a 2-day educational seminar. The provincial health care plan covers patient visits with the general practitioners. Fee-for-service for visits with the naturopathic doctor, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. A $40 annual membership allows for support group sessions, yoga classes, and cooking classes for free. | |||

| Research program description: Clinical trials and other research needs of the centre. | |||

| Integrative Medicine Program44–47 | |||

| The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Houston, TX, U.S.A. |

1998 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Weekly meeting with all im staff to discuss complex patient cases, coordinate care plans, and provide updates on previously discussed patients. Shared patient charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: Written credentialing policies for complementary medicine practitioners, involving submission of copy of degree and continuing education credits, copy of relevant licenses, two letters of reference, and professional liability insurance. There is an interview, site visits, talks with current clients, and contact with applicable licensing boards, educational institutions, and references. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Most funding is through the Center’s Division of Cancer Medicine, with other funds generated through physician consultation service and fees for acupuncture and oncology massage. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Tiered fee structure: programs at no cost (all but acupuncture and full-body massage), programs at fee-for-service, and billable services. | |||

| Research program description: Exploration of outcomes and effectiveness of complementary therapies, including treatments to reduce the negative effects of cancer diagnosis and to improve treatment outcomes and quality of life. Research focuses in the areas of mind–body medicine, acupuncture, preclinical and clinical trials of natural products, and comprehensive lifestyle change. | |||

| Klinik St. Georg Hospital48,49 | |||

| Bad Aibling, Germany | Hospital-based | ||

| Research program description: There is an active research program, but no focus is described. | |||

| Leonard P. Zakim Center50,51 | |||

| Dana Farber Cancer Institute Boston, MA, U.S.A. |

2000 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Monthly clinical practice meetings to discuss patient issues with centre’s medical director and clinical team. Shared patient charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: Formal credentialing process to address educational and experience requirements, references and practice guidelines for all complementary practitioners. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Private donations and fundraising through special events. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Various strategies for different therapies and clients, including free group sessions, reduced fee to patient, private insurance coverage, and for those on Medicaid or “free care,” 6 free treatments per therapy per calendar year. | |||

| Research program description: Clinical services offered at the centre, but not herbs and botanicals because of a lack of product standardization. | |||

| Livingston–Wheeler Medical Clinic52 | |||

| San Diego, CA, U.S.A. | 1968 | Community-based | |

| Lynda Jackson Macmillan Centre53 | |||

| Northwood, Middlesex, U.K. | 1993 | Hospital-based | |

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Partly charity based with a strong volunteer component. Other funding through block cancer contracts with cancer centre. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All therapies are free of charge. | |||

| Research program description: Patient involvement research and exploration of complementary therapies to help with side effects of cancer treatment. | |||

| Penny Brohn Cancer Care38,54,55 | |||

| Bristol, U.K. | 1980 (as the Bristol Cancer Help Centre) | Community-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Various formal group meetings. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Clients used to pay for services, but are now asked for donations for services that are otherwise received for free. | |||

| Research program description: Evaluation of the integrative model. | |||

| Rossendale Hospice56 | |||

| Lancashire, U.K. | 2000 | ||

| Research program description: Evaluation of the integrative model. | |||

| Seven Levels of Healing35,57 | |||

| Boulder and other centres in CO; Kansas City, MO; and the University of Arizona Cancer Centre, U.S.A. | 1994 | Community-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: No formal meetings or shared charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: Program facilitators are selected from existing cancer centre social work and nursing staff, and undergo an extensive training process. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Licensing fees paid by physicians at the community-based cancer centres, and by institutional funds at the U.S. National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centre. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All classes are free of charge. | |||

Research program description: Two current focuses:

|

|||

| Future plans to focus on more objective measures of the program’s impact for participants, physicians and staff. | |||

| Strang Cancer Prevention Center58 | |||

| Therapeutic Touch program59 | |||

| BC Cancer Agency, BC | 1985 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: No formal meetings or shared charts. | |||

| Accreditation and standards for complementary medicine practitioner: Level i and ii certification in Krieger–Kunz method of therapeutic touch. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Through multidisciplinary patient care committee of the cancer agency. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All sessions are free of charge. | |||

| Research program description: Psychosocial oncology. | |||

| Tumor Biology Centre60 | |||

| Freiburg, Germany | 1993 | Hospital-based | |

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Weekly interdisciplinary ward conference and weekly psychosocial case conference. Both serve to coordinate and plan patient treatment. Shared patient charts. | |||

| Research program description: Psychooncology and rehabilitation in 3 areas: psychosocial aspects of complementary medicine, evaluation of psychosocial support programs, and evaluation of rehabilitation programs. | |||

| University College London Hospital61 | |||

| London, U.K. | Hospital-based | ||

| Means for practitioner collaboration: Multidisciplinary handover and team meetings. Shared patient charts. | |||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations and some government funding. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All therapies are free of charge. | |||

| Research program description: Clinical trials. | |||

| University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center (formerly Ireland Cancer Center)62 | |||

| Cleveland, OH, U.S.A. | Hospital-based | ||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Support from foundations and private donors. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Most services are provided free of charge. There is a charge for acupuncture, energy-based therapies, massage therapy, and psychotherapy. | |||

| Name not provided63 | |||

| U.K. | Hospital-based | ||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations and government funding. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: All therapies are free of charge. | |||

| Name not provided64 | |||

| Southeast England, U.K. | Hospital-based | ||

| Day-to-day funding and operations: Charitable donations. | |||

| Complementary therapy cost recovery: Free of charge with request for discretionary donation after 4 sessions of any therapy. Acupuncture and counseling are always free. | |||

| Research program description: No active research program. | |||

Overall, funding mechanisms show variability and variety, but some within-country similarities are notable. The programs in our sample that operate in England are financed partly through charitable donations and public (National Health Service) or hospital funds, with some volunteer support. Those programs exclusively provide complementary therapies free of charge, sometimes with a donation request and a limit placed on the number of hours or sessions that clients can access. Programs within the United States also rely on support from foundations, private donors, and (in 1 case) research grants, but financing is also assisted through hospital budgets (where relevant), third-party billing, and direct billing to patients. Those programs most commonly recover costs from private insurance plans and direct patient payment, but most also provide at least some therapies free of charge or at a reduced rate.

3.5. Process of Care

Information about the initial patient assessment procedure was reported for 20 programs (69%). Initial assessments commonly involve a structured consultation or consultations with one or more therapists to collaboratively develop a care plan (n = 6, 21%); patient education and advice (n = 5, 17%); a structured introduction to available services (n = 4, 14%); a holistic (that is, some combination of physical, psychological, social, or spiritual) assessment (n = 4, 14%); a medical history and a history of complementary and conventional therapy use (n = 3, 10%); an assessment of patient needs, concerns, and expectations (n = 3, 10%); and other assessments such as physical exams, psychological assessments, and lifestyle consultations. Further, three quarters of the programs (n = 21, 72%) reported some details about patient flow through the integrative programs (n = 8, 28%), although the level of detail reported varied widely between programs. The integrative oncology programs included in our review used a variety of elements: tours, orientations, or structured introductory sessions before the start of care; individualized diet or supplementation programs or advice; telephone help lines; routine patient evaluation and follow-up consultations; referral to community-based resources; various means of internal referrals; and patient education, among others.

Some programs are inpatient-only programs, others are outpatient-only, and some serve both inpatients and outpatients. Programs also vary by the level of patient involvement in their own care and decision-making, with a tendency toward collaborative decision-making between therapists, patients, and their families. Some programs are very structured, with a common process outlined for each participant or client within the program, and others are very unstructured and rely on patients to identify and schedule appointments for their therapies of choice. Some programs require a written referral or clearance from conventional practitioners to proceed with complementary treatment, and others rely on only informal communication between complementary and conventional cancer professionals, often initiated by patients.

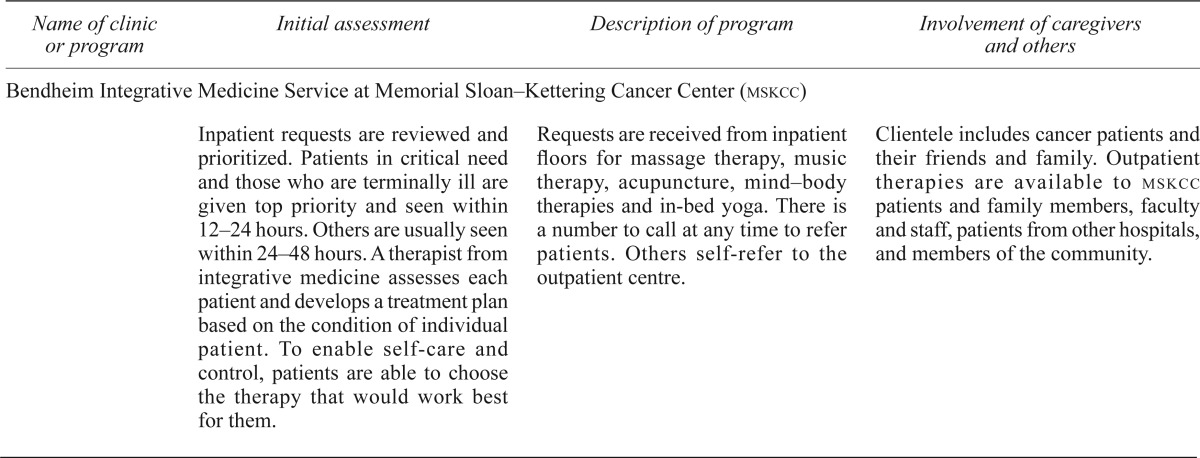

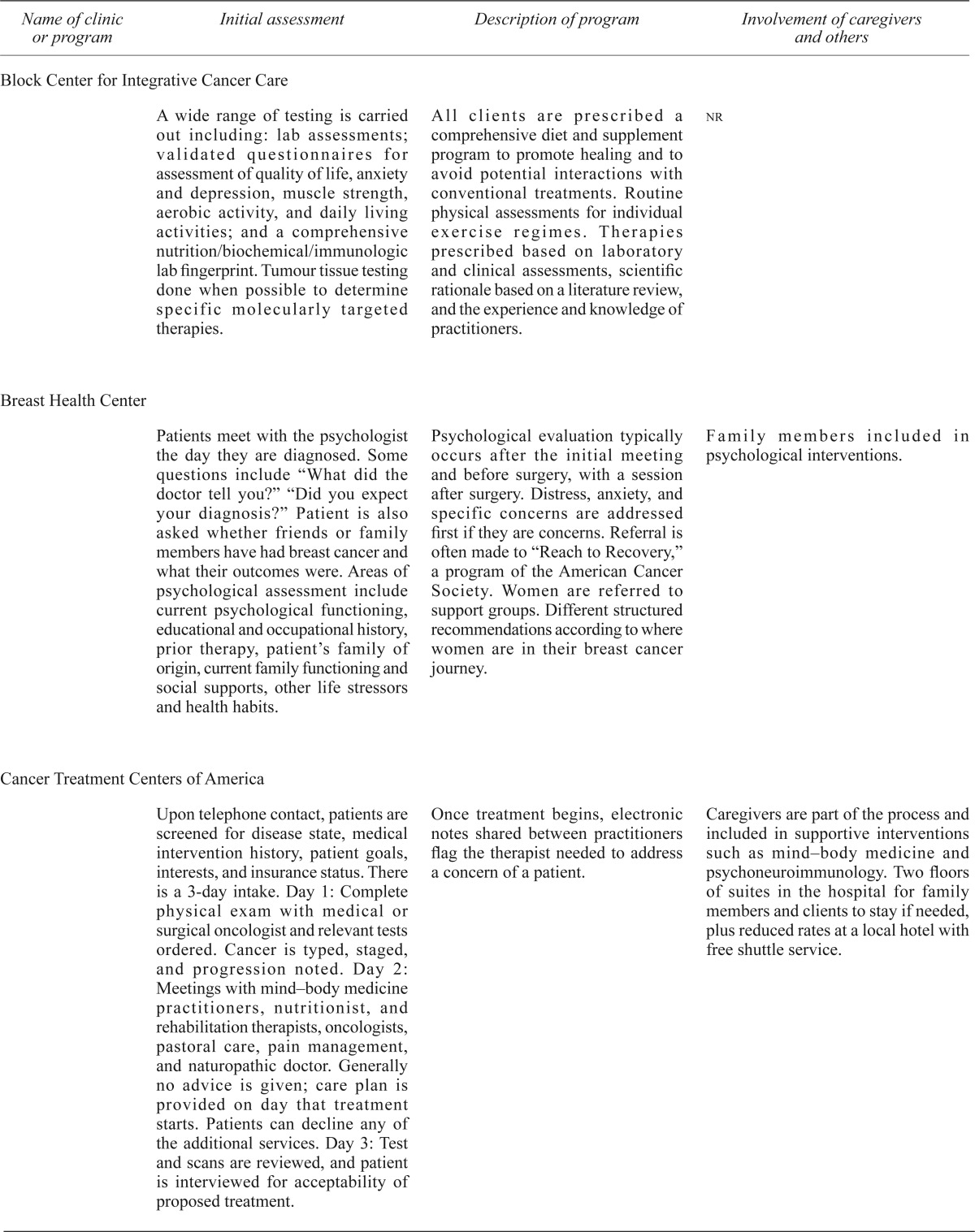

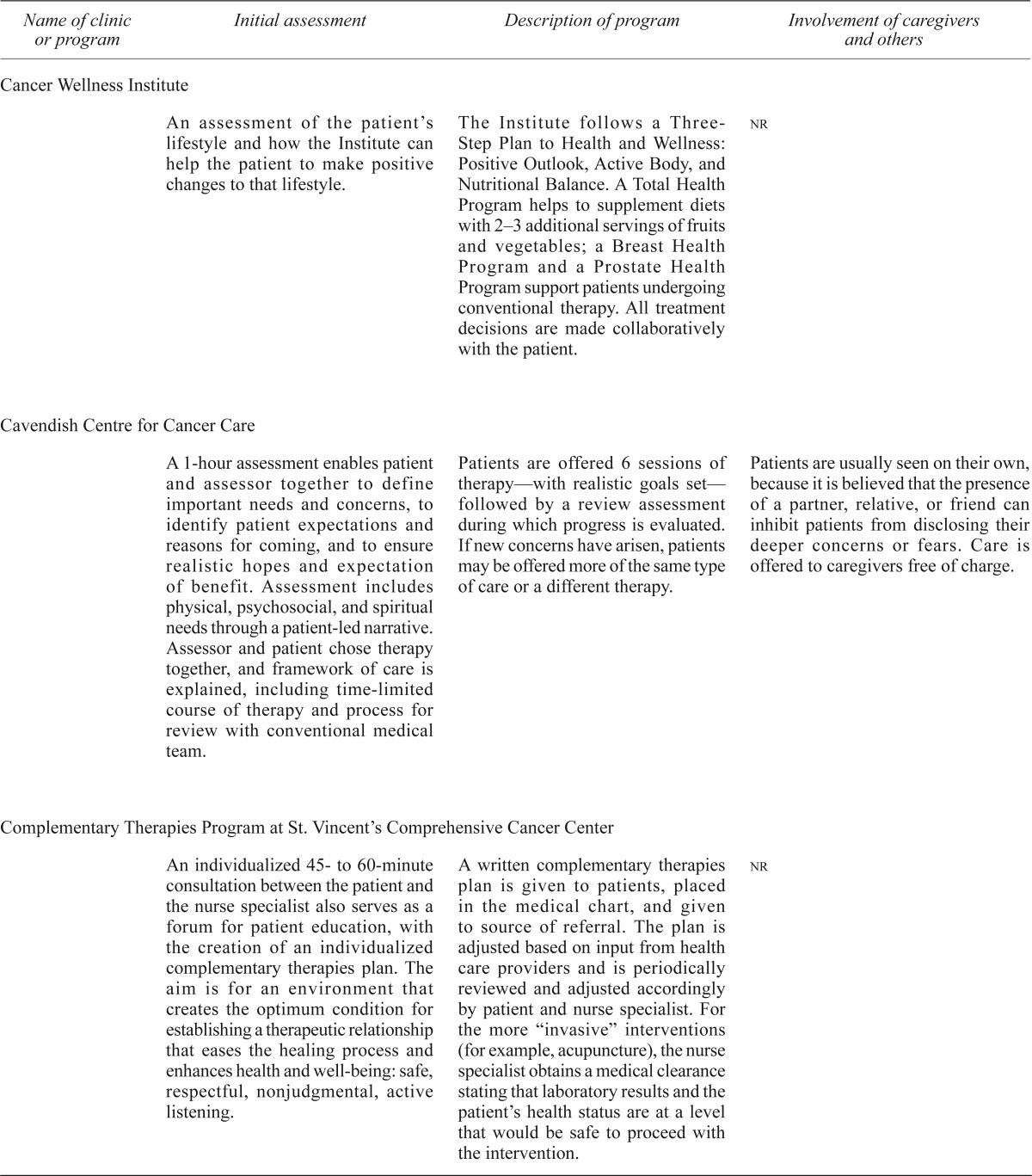

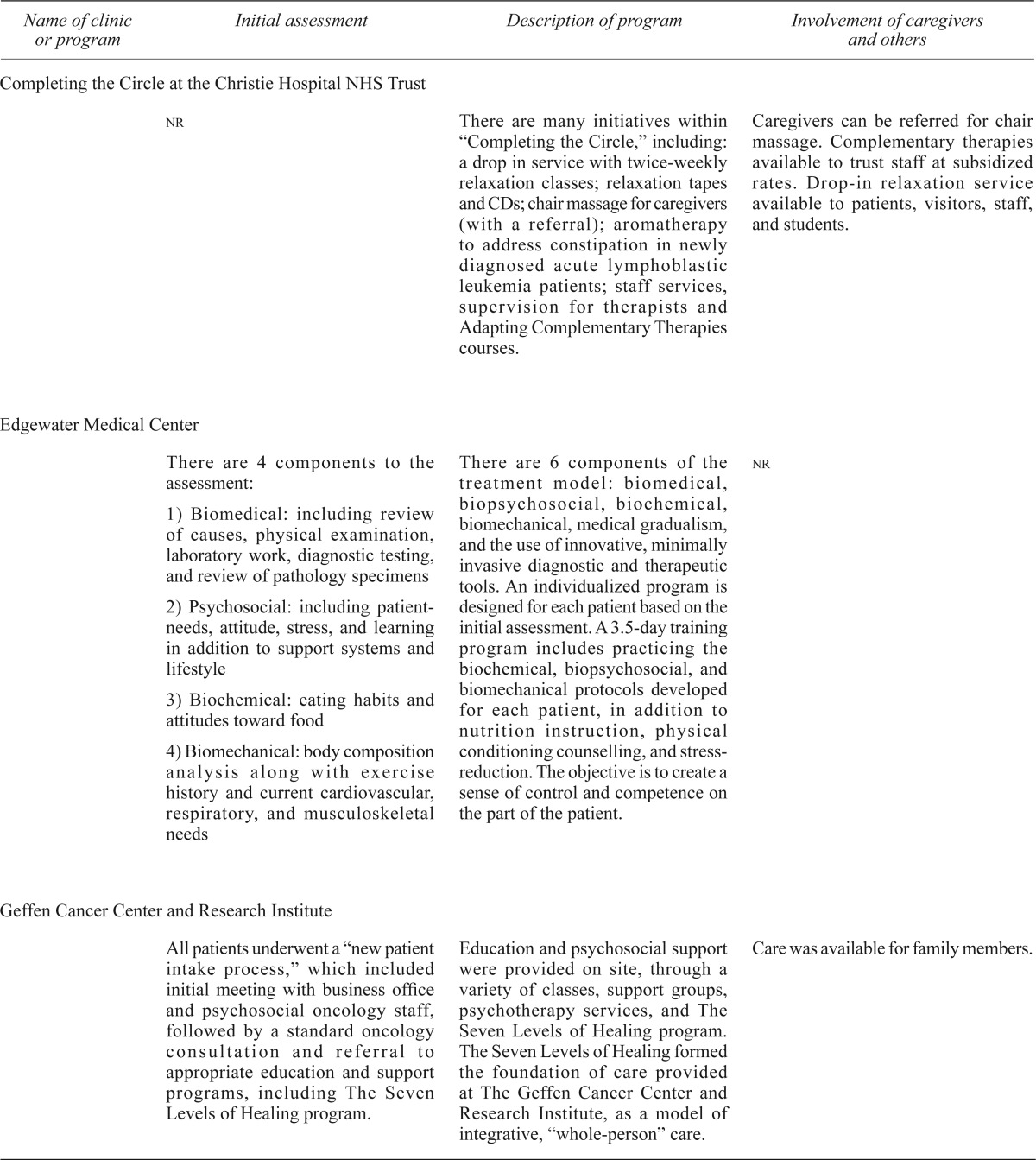

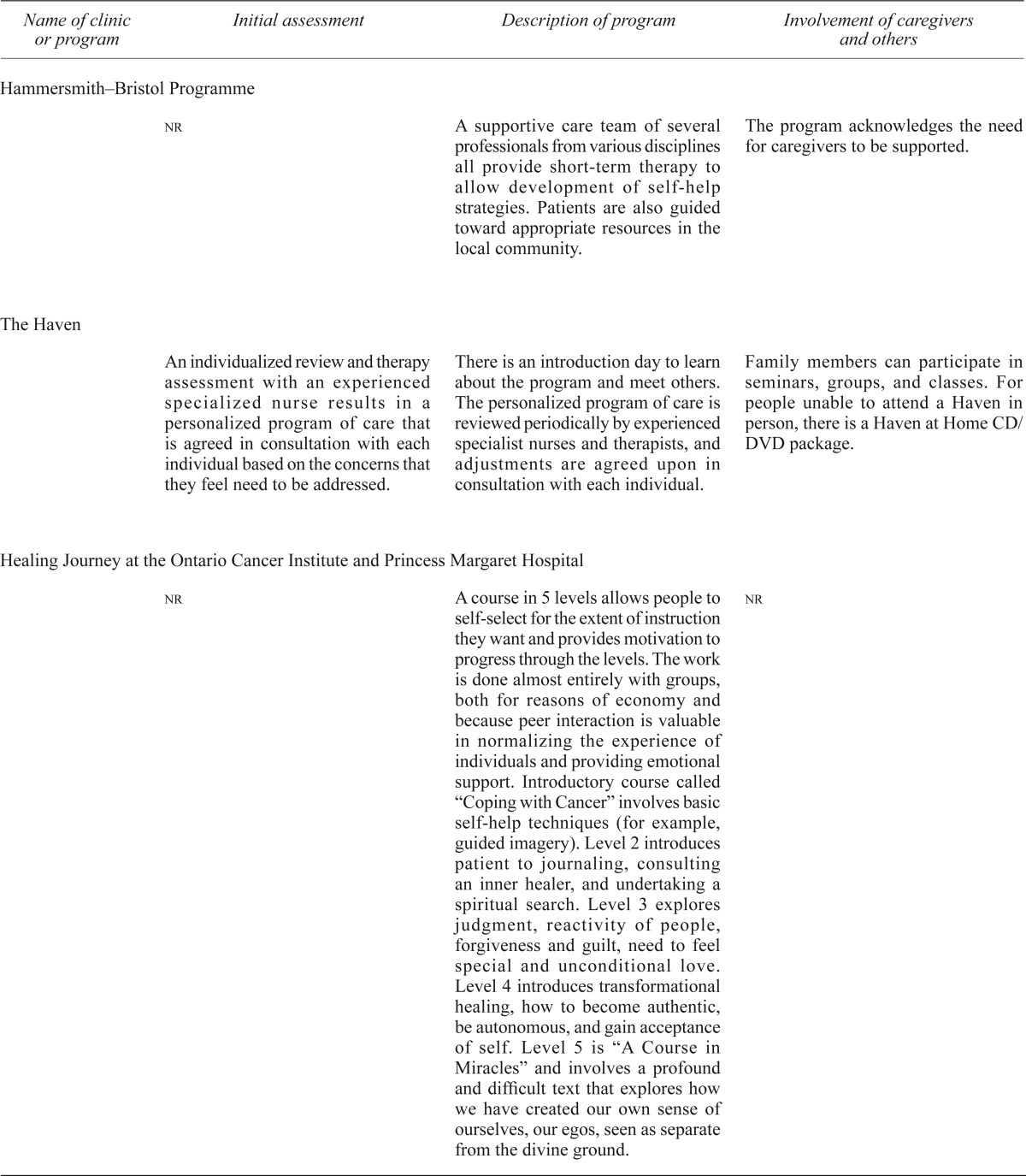

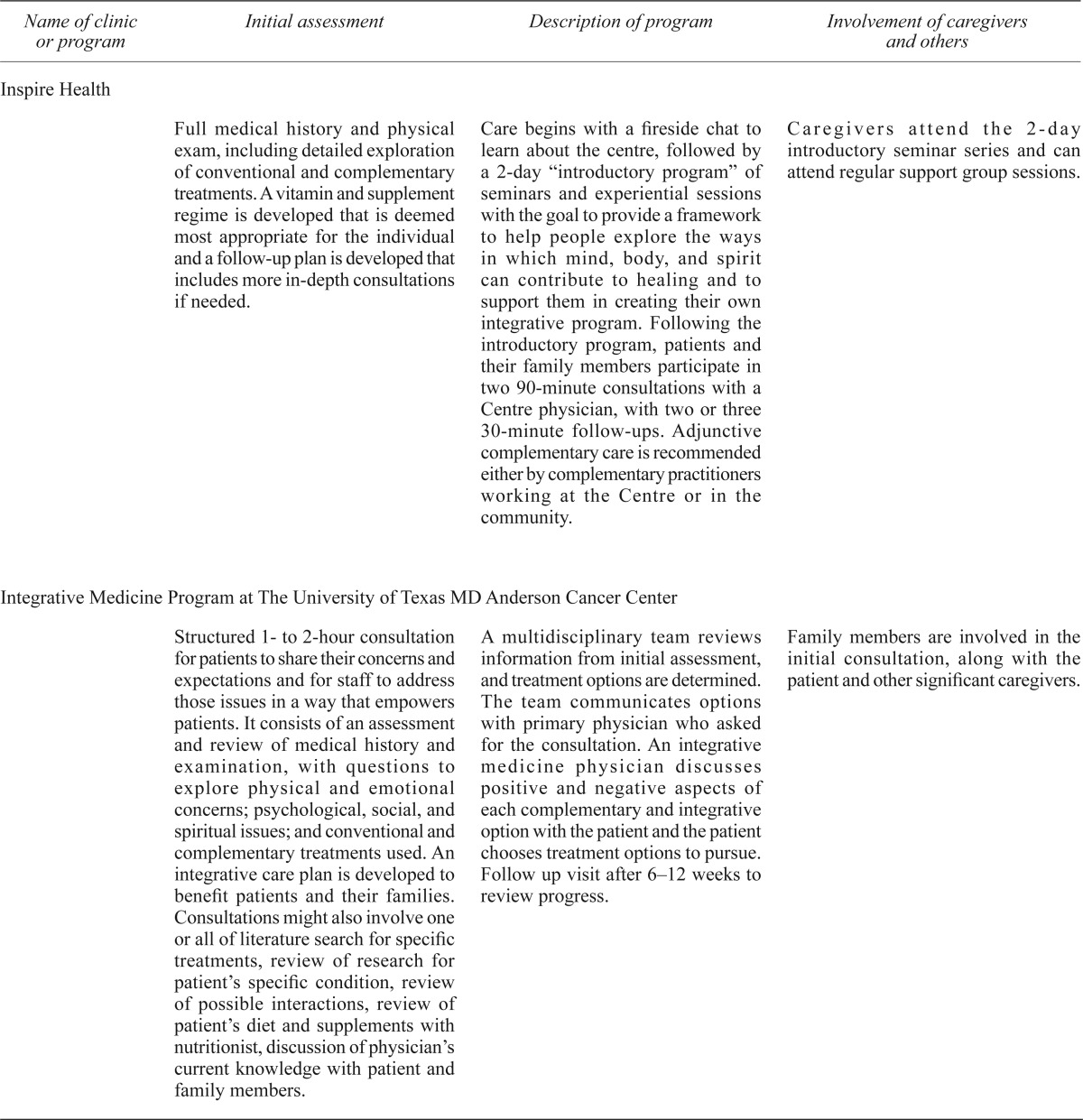

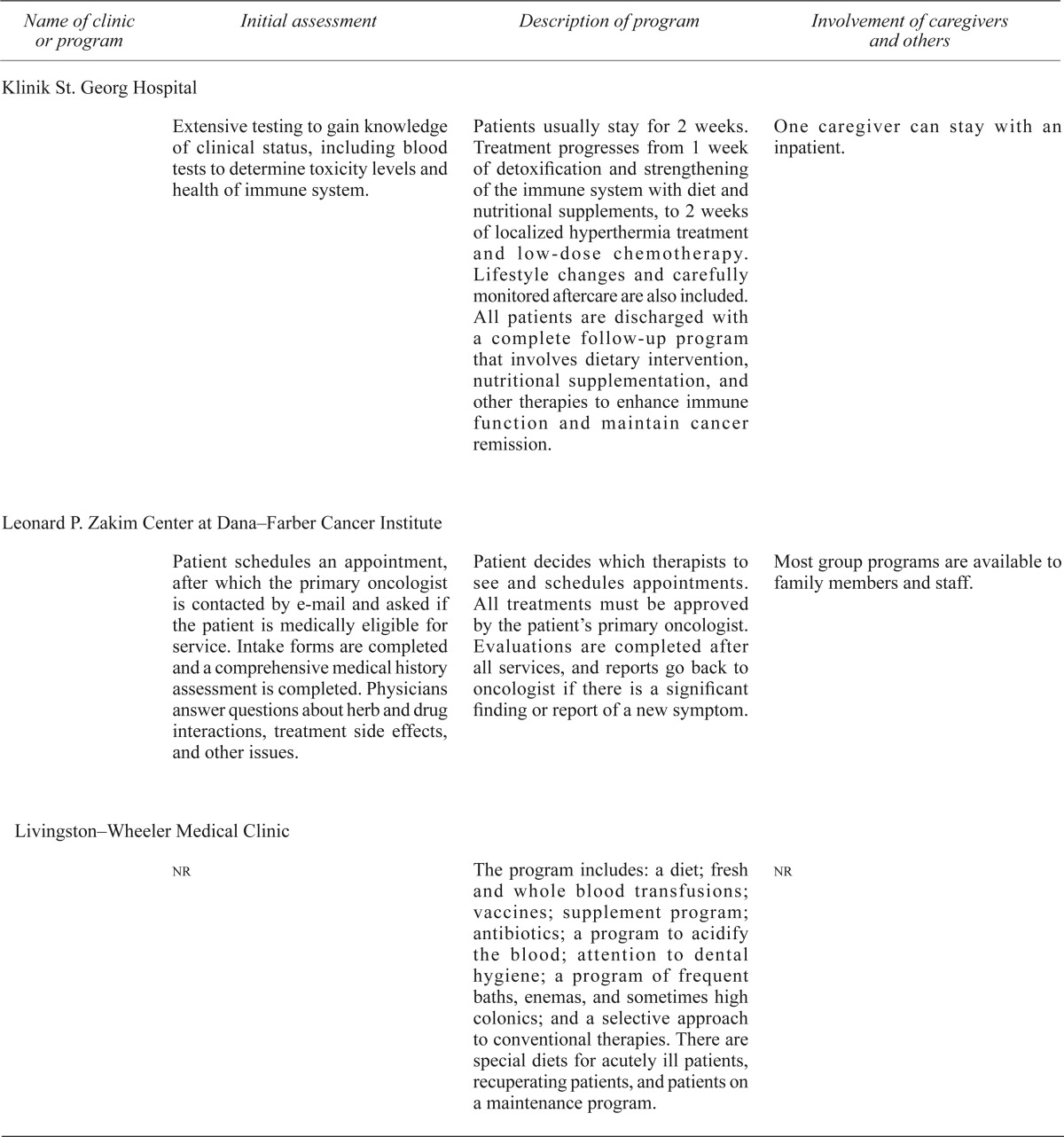

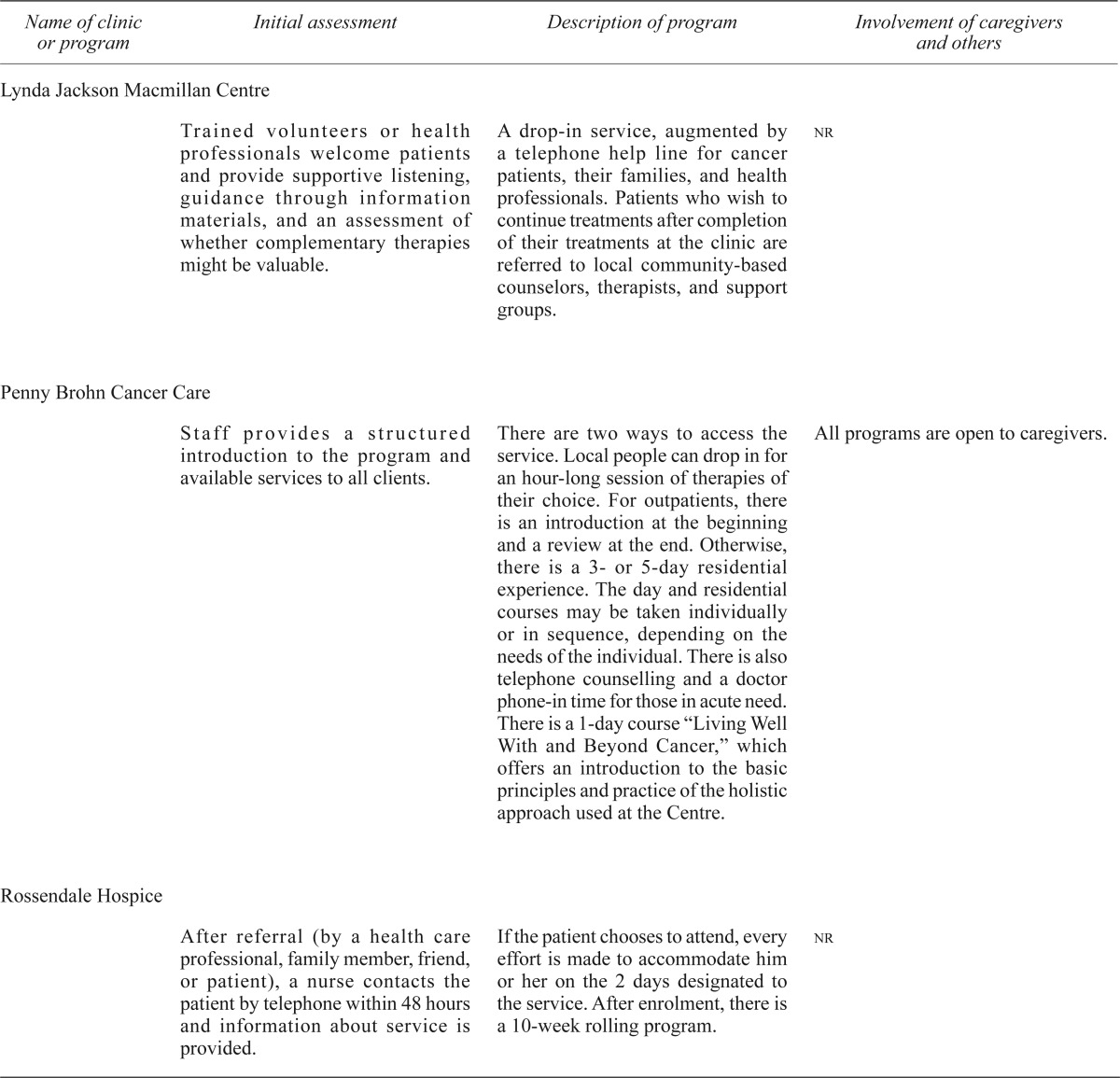

Clearly, the complexity of, and the variety within, programs cannot be summarized succinctly, and so Table ii provides a brief description of the process of care within each program.

TABLE II.

Description of patient care and flow in integrative oncology programs

| Name of clinic or program | Initial assessment | Description of program | Involvement of caregivers and others |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bendheim Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (mskcc) | |||

| Inpatient requests are reviewed and prioritized. Patients in critical need and those who are terminally ill are given top priority and seen within 12–24 hours. Others are usually seen within 24–48 hours. A therapist from integrative medicine assesses each patient and develops a treatment plan based on the condition of individual patient. To enable self-care and control, patients are able to choose the therapy that would work best for them. | Requests are received from inpatient floors for massage therapy, music therapy, acupuncture, mind–body therapies and in-bed yoga. There is a number to call at any time to refer patients. Others self-refer to the outpatient centre. | Clientele includes cancer patients and their friends and family. Outpatient therapies are available to mskcc patients and family members, faculty and staff, patients from other hospitals, and members of the community. | |

| Block Center for Integrative Cancer Care | |||

| A wide range of testing is carried out including: lab assessments; validated questionnaires for assessment of quality of life, anxiety and depression, muscle strength, aerobic activity, and daily living activities; and a comprehensive nutrition/biochemical/immunologic lab fingerprint. Tumour tissue testing done when possible to determine specific molecularly targeted therapies. | All clients are prescribed a comprehensive diet and supplement program to promote healing and to avoid potential interactions with conventional treatments. Routine physical assessments for individual exercise regimes. Therapies prescribed based on laboratory and clinical assessments, scientific rationale based on a literature review, and the experience and knowledge of practitioners. | nr | |

| Breast Health Center | |||

| Patients meet with the psychologist the day they are diagnosed. Some questions include “What did the doctor tell you?” “Did you expect your diagnosis?” Patient is also asked whether friends or family members have had breast cancer and what their outcomes were. Areas of psychological assessment include current psychological functioning, educational and occupational history, prior therapy, patient’s family of origin, current family functioning and social supports, other life stressors and health habits. | Psychological evaluation typically occurs after the initial meeting and before surgery, with a session after surgery. Distress, anxiety, and specific concerns are addressed first if they are concerns. Referral is often made to “Reach to Recovery,” a program of the American Cancer Society. Women are referred to support groups. Different structured recommendations according to where women are in their breast cancer journey. | Family members included in psychological interventions. | |

| Cancer Treatment Centers of America | |||

| Upon telephone contact, patients are screened for disease state, medical intervention history, patient goals, interests, and insurance status. There is a 3-day intake. Day 1: Complete physical exam with medical or surgical oncologist and relevant tests ordered. Cancer is typed, staged, and progression noted. Day 2: Meetings with mind–body medicine practitioners, nutritionist, and rehabilitation therapists, oncologists, pastoral care, pain management, and naturopathic doctor. Generally no advice is given; care plan is provided on day that treatment starts. Patients can decline any of the additional services. Day 3: Test and scans are reviewed, and patient is interviewed for acceptability of proposed treatment. | Once treatment begins, electronic notes shared between practitioners flag the therapist needed to address a concern of a patient. | Caregivers are part of the process and included in supportive interventions such as mind–body medicine and psychoneuroimmunology. Two floors of suites in the hospital for family members and clients to stay if needed, plus reduced rates at a local hotel with free shuttle service. | |

| Cancer Wellness Institute | |||

| An assessment of the patient’s lifestyle and how the Institute can help the patient to make positive changes to that lifestyle. | The Institute follows a Three-Step Plan to Health and Wellness: Positive Outlook, Active Body, and Nutritional Balance. A Total Health Program helps to supplement diets with 2–3 additional servings of fruits and vegetables; a Breast Health Program and a Prostate Health Program support patients undergoing conventional therapy. All treatment decisions are made collaboratively with the patient. | nr | |

| Cavendish Centre for Cancer Care | |||

| A 1-hour assessment enables patient and assessor together to define important needs and concerns, to identify patient expectations and reasons for coming, and to ensure realistic hopes and expectation of benefit. Assessment includes physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs through a patient-led narrative. Assessor and patient chose therapy together, and framework of care is explained, including time-limited course of therapy and process for review with conventional medical team. | Patients are offered 6 sessions of therapy—with realistic goals set—followed by a review assessment during which progress is evaluated. If new concerns have arisen, patients may be offered more of the same type of care or a different therapy. | Patients are usually seen on their own, because it is believed that the presence of a partner, relative, or friend can inhibit patients from disclosing their deeper concerns or fears. Care is offered to caregivers free of charge. | |

| Complementary Therapies Program at St. Vincent’s Comprehensive Cancer Center | |||

| An individualized 45- to 60-minute consultation between the patient and the nurse specialist also serves as a forum for patient education, with the creation of an individualized complementary therapies plan. The aim is for an environment that creates the optimum condition for establishing a therapeutic relationship that eases the healing process and enhances health and well-being: safe, respectful, nonjudgmental, active listening. | A written complementary therapies plan is given to patients, placed in the medical chart, and given to source of referral. The plan is adjusted based on input from health care providers and is periodically reviewed and adjusted accordingly by patient and nurse specialist. For the more “invasive” interventions (for example, acupuncture), the nurse specialist obtains a medical clearance stating that laboratory results and the patient’s health status are at a level that would be safe to proceed with the intervention. | nr | |

| Completing the Circle at the Christie Hospital NHS Trust | |||

| nr | There are many initiatives within “Completing the Circle,” including: a drop in service with twice-weekly relaxation classes; relaxation tapes and CDs; chair massage for caregivers (with a referral); aromatherapy to address constipation in newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients; staff services, supervision for therapists and Adapting Complementary Therapies courses. | Caregivers can be referred for chair massage. Complementary therapies available to trust staff at subsidized rates. Drop-in relaxation service available to patients, visitors, staff, and students. | |

| Edgewater Medical Center | |||

There are 4 components to the assessment:

|

There are 6 components of the treatment model: biomedical, biopsychosocial, biochemical, biomechanical, medical gradualism, and the use of innovative, minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic tools. An individualized program is designed for each patient based on the initial assessment. A 3.5-day training program includes practicing the biochemical, biopsychosocial, and biomechanical protocols developed for each patient, in addition to nutrition instruction, physical conditioning counselling, and stress-reduction. The objective is to create a sense of control and competence on the part of the patient. | nr | |

| Geffen Cancer Center and Research Institute | |||

| All patients underwent a “new patient intake process,” which included initial meeting with business office and psychosocial oncology staff, followed by a standard oncology consultation and referral to appropriate education and support programs, including The Seven Levels of Healing program. | Education and psychosocial support were provided on site, through a variety of classes, support groups, psychotherapy services, and The Seven Levels of Healing program. The Seven Levels of Healing formed the foundation of care provided at The Geffen Cancer Center and Research Institute, as a model of integrative, “whole-person” care. | Care was available for family members. | |

| Hammersmith–Bristol Programme | |||

| nr | A supportive care team of several professionals from various disciplines all provide short-term therapy to allow development of self-help strategies. Patients are also guided toward appropriate resources in the local community. | The program acknowledges the need for caregivers to be supported. | |

| The Haven | |||

| An individualized review and therapy assessment with an experienced specialized nurse results in a personalized program of care that is agreed in consultation with each individual based on the concerns that they feel need to be addressed. | There is an introduction day to learn about the program and meet others. The personalized program of care is reviewed periodically by experienced specialist nurses and therapists, and adjustments are agreed upon in consultation with each individual. | Family members can participate in seminars, groups, and classes. For people unable to attend a Haven in person, there is a Haven at Home CD/DVD package. | |

| Healing Journey at the Ontario Cancer Institute and Princess Margaret Hospital | |||

| nr | A course in 5 levels allows people to self-select for the extent of instruction they want and provides motivation to progress through the levels. The work is done almost entirely with groups, both for reasons of economy and because peer interaction is valuable in normalizing the experience of individuals and providing emotional support. Introductory course called “Coping with Cancer” involves basic self-help techniques (for example, guided imagery). Level 2 introduces patient to journaling, consulting an inner healer, and undertaking a spiritual search. Level 3 explores judgment, reactivity of people, forgiveness and guilt, need to feel special and unconditional love. Level 4 introduces transformational healing, how to become authentic, be autonomous, and gain acceptance of self. Level 5 is “A Course in Miracles” and involves a profound and difficult text that explores how we have created our own sense of ourselves, our egos, seen as separate from the divine ground. | nr | |

| Inspire Health | |||

| Full medical history and physical exam, including detailed exploration of conventional and complementary treatments. A vitamin and supplement regime is developed that is deemed most appropriate for the individual and a follow-up plan is developed that includes more in-depth consultations if needed. | Care begins with a fireside chat to learn about the centre, followed by a 2-day “introductory program” of seminars and experiential sessions with the goal to provide a framework to help people explore the ways in which mind, body, and spirit can contribute to healing and to support them in creating their own integrative program. Following the introductory program, patients and their family members participate in two 90-minute consultations with a Centre physician, with two or three 30-minute follow-ups. Adjunctive complementary care is recommended either by complementary practitioners working at the Centre or in the community. | Caregivers attend the 2-day introductory seminar series and can attend regular support group sessions. | |

| Integrative Medicine Program at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center | |||

| Structured 1- to 2-hour consultation for patients to share their concerns and expectations and for staff to address those issues in a way that empowers patients. It consists of an assessment and review of medical history and examination, with questions to explore physical and emotional concerns; psychological, social, and spiritual issues; and conventional and complementary treatments used. An integrative care plan is developed to benefit patients and their families. Consultations might also involve one or all of literature search for specific treatments, review of research for patient’s specific condition, review of possible interactions, review of patient’s diet and supplements with nutritionist, discussion of physician’s current knowledge with patient and family members. | A multidisciplinary team reviews information from initial assessment, and treatment options are determined. The team communicates options with primary physician who asked for the consultation. An integrative medicine physician discusses positive and negative aspects of each complementary and integrative option with the patient and the patient chooses treatment options to pursue. Follow up visit after 6–12 weeks to review progress. | Family members are involved in the initial consultation, along with the patient and other significant caregivers. | |

| Klinik St. Georg Hospital | |||

| Extensive testing to gain knowledge of clinical status, including blood tests to determine toxicity levels and health of immune system. | Patients usually stay for 2 weeks. Treatment progresses from 1 week of detoxification and strengthening of the immune system with diet and nutritional supplements, to 2 weeks of localized hyperthermia treatment and low-dose chemotherapy. Lifestyle changes and carefully monitored aftercare are also included. All patients are discharged with a complete follow-up program that involves dietary intervention, nutritional supplementation, and other therapies to enhance immune function and maintain cancer remission. | One caregiver can stay with an inpatient. | |

| Leonard P. Zakim Center at Dana–Farber Cancer Institute | |||

| Patient schedules an appointment, after which the primary oncologist is contacted by e-mail and asked if the patient is medically eligible for service. Intake forms are completed and a comprehensive medical history assessment is completed. Physicians answer questions about herb and drug interactions, treatment side effects, and other issues. | Patient decides which therapists to see and schedules appointments. All treatments must be approved by the patient’s primary oncologist. Evaluations are completed after all services, and reports go back to oncologist if there is a significant finding or report of a new symptom. | Most group programs are available to family members and staff. | |

| Livingston–Wheeler Medical Clinic | |||

| nr | The program includes: a diet; fresh and whole blood transfusions; vaccines; supplement program; antibiotics; a program to acidify the blood; attention to dental hygiene; a program of frequent baths, enemas, and sometimes high colonics; and a selective approach to conventional therapies. There are special diets for acutely ill patients, recuperating patients, and patients on a maintenance program. | nr | |

| Lynda Jackson Macmillan Centre | |||

| Trained volunteers or health professionals welcome patients and provide supportive listening, guidance through information materials, and an assessment of whether complementary therapies might be valuable. | A drop-in service, augmented by a telephone help line for cancer patients, their families, and health professionals. Patients who wish to continue treatments after completion of their treatments at the clinic are referred to local community-based counselors, therapists, and support groups. | nr | |

| Penny Brohn Cancer Care | |||

| Staff provides a structured introduction to the program and available services to all clients. | There are two ways to access the service. Local people can drop in for an hour-long session of therapies of their choice. For outpatients, there is an introduction at the beginning and a review at the end. Otherwise, there is a 3- or 5-day residential experience. The day and residential courses may be taken individually or in sequence, depending on the needs of the individual. There is also telephone counselling and a doctor phone-in time for those in acute need. There is a 1-day course “Living Well With and Beyond Cancer,” which offers an introduction to the basic principles and practice of the holistic approach used at the Centre. | All programs are open to caregivers. | |

| Rossendale Hospice | |||

| After referral (by a health care professional, family member, friend, or patient), a nurse contacts the patient by telephone within 48 hours and information about service is provided. | If the patient chooses to attend, every effort is made to accommodate him or her on the 2 days designated to the service. After enrolment, there is a 10-week rolling program. | nr | |

| Seven Levels of Healing | |||

| nr | The Seven Levels of Healing is a structured, highly interactive education and support program offered in weekly 2-hour afternoon or evening group sessions over 7 weeks. The sessions include didactic information, group and individual exercises, sharing circles, and guided imagery processes. Each weekly session focuses on one of the seven levels of healing:

|

All programs are available to caregivers and health professionals. | |

| Strang Cancer Prevention Center | |||

| nr | nr | nr | |

| Therapeutic Touch program at the BC Cancer Agency | |||

| The supervising counsellor conducts a pretreatment assessment with each patient to determine their cognitive understanding and comfort with the purposes of therapeutic touch, their medical diagnosis, and their suitability for treatment. | Sessions are booked for 30–45 minutes, with 4–6 patients treated at the same time. Each clinic begins with a centering meditation for the practitioners. The volunteers perform an initial hands-on assessment of the energy field around a patient’s clothed body and then proceed with the treatment. A check-in for feedback is held at the end of the treatment, and a debriefing session for the volunteers by counsellors occurs at the end of each clinic. | Program available only to cancer patients. | |

| Tumor Biology Centre | |||

| nr | nr | nr | |

| University College London Hospital | |||

| Therapists explain the therapies on offer and give patients a leaflet with the details of the therapy and what to expect. | Treatments and counselling for inpatients takes place at the bedside. The service is designed to respond immediately to the patient’s daily needs and appointments are not needed in advance. Therapists arrive on the ward and liaise with nursing staff and patients to offer treatment. Once patients are discharged from the hospital they are entitled to 4 treatments as outpatients. | All programs are open to family members. | |

| University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center | |||

| nr | There is a tour and an orientation to the centre. Patients are actively involved in treatment and decision-making through the development of a personal healing plan in conjunction with centre staff. | Caregivers are also offered care. | |

| Name not provided | |||

| nr | nr | nr | |

| Name not provided | |||

| Patients enter a waiting area and are greeted by trained volunteers who listen to their issues and then suggest various complementary therapies. | nr | All programs available to anyone touched by cancer, including partners, caregivers, and friends of cancer patients and National Health Service staff. | |

3.6. Research and Evaluation within Integrative Oncology Programs

More than two thirds of the programs (n = 20, 69%) reported maintaining an active research program or an evaluation strategy, or both (n = 16, 55%). Although little information was reported about participant recruitment strategies, research personnel, and a funding structure, the focus of the research programs is quite clearly clinical trials of therapies currently offered within the program, therapies being considered within the program, or evaluation of a specific model of integrative care. Some programs include a qualitative research component as a means to describe the treatment model and possible outcomes in the words of patients who have chosen an integrative approach. All programs have framed their research program in terms of the use of complementary therapies for cancer- and cancer treatment–related symptoms, but not as a cancer cure.

Half the programs (n = 16, 55%) in our sample reported consistently measuring patient outcomes as a means to evaluate the program. Of the remaining programs, 2 (7%) specifically reported not conducting program evaluations, and 11 (38%) were silent on that issue. A range of outcomes are assessed across the programs, including quality of life, cancer- and cancer treatment–related symptoms, well-being, survival, patient-identified concerns and benefits, and descriptions of patient experiences within the program. Some programs rely on researcher-developed questionnaires to assess patient outcomes; others rely on standardized measures. Most commonly, a baseline assessment is made when a patient is first referred to the program, with follow-up occurring after treatment or after a predetermined amount of time.

For evaluation purposes, 3 programs (10%) reported collecting data other than patient outcome data, including clinic volume, therapies used, reasons for referral, financial assistance requests, and client feedback on aspects of the program they liked or would like to see changed. Results of the evaluation programs are used to improve the treatment approach or to develop a case for expansion of the program; they are sometimes published in academic journals or presented at scientific conferences.

4. DISCUSSION

Our review highlights the internationally growing number and diversity of integrative oncology programs that share a common vision to provide whole-person and patient-centred care, inclusive of evidence-based complementary and conventional medicine. At least 29 such programs are operating internationally, with the 1960s marking the beginnings of such programs and with most having been established since the 1990s. More programs are certainly in operation than are included in our review, given that we reviewed only the English, French, and German academic literature and searched only English-language databases and journals. Most of the programs included in our review are based in England or the United States, which likely does not reflect the actual pattern of integrative oncology programs internationally. For example, in Germany, complementary approaches to cancer care have historically been fairly well integrated with conventional care, although our review captured only 2 German programs. We are also aware of several integrative medicine programs within the United States that include a large cancer focus, but that are not specifically integrative oncology programs, including the Program in Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona65, the University of California at San Francisco Osher Center for Integrative Medicine66, the Johns Hopkins Complementary and Integrative Medicine Service67, and the Mayo Complementary and Integrative Medicine Program68. There are certainly several more examples of integrative oncology programs than were included in our review, indicating that integrative oncology programs are even more varied than described here.

At least part of the observed variety across integrative oncology programs can be explained by differences in the political, social, and organizational environments in which they were developed; other factors are the varied backgrounds, skills, and experiences of the leaders driving program development69,70. The varied environments have resulted in a wide range of approaches to development and operation, collaboration, communication, and cost recovery. Most definitions of integrative oncology found in the literature refer to a novel and idealized form of health care practice that focuses on the whole person and that includes a new structure and new processes for shared patient management, shared care, and shared overall values and goals10,11,43. However, although the programs included in our review clearly strive to achieve that vision, most fall short of implementing the full spectrum of structures and processes expected within truly integrative practices. For example, fewer than half the programs we reviewed reported holding regular inter-professional team meetings or sharing charts with the interprofessional team, processes that are both fundamental to providing seamless, interdisciplinary care inclusive of both conventional and complementary medicine. This lack of agreement between idealized and real-world practice should not, however, reflect poorly on the real-world examples that we reviewed; instead, it reflects the context-dependent nature of those programs70. The included integrative oncology programs are quite likely representations of what is possible in the current political, social, and organizational environment in which complementary medicine remains on the margins of mainstream care. Regardless, the observed differences between idealized and real-world practice does raise a question: Just how “integrative” is the discipline of integrative oncology at present? Perhaps our findings signal a need to develop a scale or other tool to help gauge progress towards the vision. Further, the observed variety in operational models highlights the need for all programs—developing and existing—to maintain a comprehensive understanding of factors that could influence sustainability: for example policies, regulations, technology, and patient demands. Through regular process evaluations, integrative oncology programs can adapt to remain relevant and effective in the community they serve69.

The articles included in this review are only snapshots of programs at certain points in time, and therefore our review of them does not capture the complexity and fluidity of programs as they adapt and change within their environment. Similarly, we are tied to a reported view of included programs, a view that is inherently limited by the space constraints of the written record and that holds the potential for selective or idealized reporting. To enhance data reliability and to minimize missing data, we attempted to contact personnel within each of the included programs. We were somewhat successful, but we were not able to talk to a representative from every program. It is therefore likely that some of the information reported here is out of date or otherwise no longer applicable. For example, we are aware that at least 1 of the included programs, the Geffen Cancer Center and Research Institute, no longer operates in the reported format. The same could also be true for other programs.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our review suggests that distinct integrative oncology models are operating within England and the United States, with few published examples from other countries to be able to draw reliable comparisons. A mixture of both hospital- and community-based programs operate in each country, but the way in which the day-to-day operations are financed, the programs are administered, and costs are recovered from clients vary. Programs in England are exclusively funded through charitable donations and public or hospital funds, with some volunteer support; programs in the United States sometimes use such sources and additionally obtain support through third-party billing, direct billing to patients, and research grants. Further, programs in England exclusively provide care free of charge, but most place a limit on services that clients can receive. Within the United States, free care is not uncommon, but payment is usually involved, which might be recovered through insurance or direct patient payment.

Given the growth and innovation in the integrative oncology field, we hope that this review provides a starting point to navigate some of the issues involved in developing and establishing such programs. It should be instructive for practitioners, researchers, administrators, and funders working in an integrative oncology environment to read of the varied examples and factors that influence program development. Integrative oncology attempts to bridge numerous therapeutic modalities and philosophies of care, and related programs may therefore not be supported by all types of practitioners despite being requested by many patients. Furthermore, implementation is complicated by a need for system- and cultural-level changes and lack of a universal definition. Ultimately, implementation requires local collaboration and strong and committed leadership to be successful. If people working in these environments continue to publish descriptions of their experiences with program development and operation, including evaluations of the process and outcomes of their programs, the field can continue to demonstrate value that can translate across disciplines in oncology and within an evolving health care system.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the help of Marie-Jasmine Parsi in sourcing the full-text articles for review, Isabelle Gaboury for reviewing the search protocol and suggesting possible information sources, and information specialist Jessie McGowan for conducting the systematic search. We also extend our thanks to the people from the integrative oncology programs who responded to our questions and to the experts we approached for providing citations to investigate. This study is supported by a grant from the Lotte and John Hecht Memorial Foundation.

APPENDIX A. SEARCH STRATEGY FOR MEDLINE

Ovid medline 1950 to December, Week 5, 2009

| Step | Search | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Integrative Medicine/ | 138 |

| 2 | ((integrative or integrated) adj2 (oncolog$ or cancer)).tw. | 198 |

| 3 | ((integrative or integrated) adj2 (care or service or model or clinic* or program* or health* or medicine or healing or therap* or treat*)).tw. | 9,193 |

| 4 | or/1–3 | 9,409 |

| 5 | exp Complementary Therapies/ | 136,580 |

| 6 | medicine, ayurvedic/ | 1,344 |

| 7 | ((alternative or Complementary or Holistic) adj2 (medicine or health*)).tw. | 6,298 |

| 8 | (Whole person care or Patient centered).tw. | 2,400 |

| 9 | (chinese or asian or oriental).tw. | 93,170 |

| 10 | or/5–9 | 226,718 |

| 11 | ((conventional or allopathic or western or biomedic*) adj medicine).tw. | 2,433 |

| 12 | 10 and 11 | 2,011 |

| 13 | 4 or 12 | 11,259 |

| 14 | models, organizational/ | 11,384 |

| 15 | og.fs. | 298,684 |

| 16 | Cooperative Behavior/ | 16,544 |

| 17 | exp Health Services Administration/ | 1,595,351 |

| 18 | (model or models).tw. | 998,575 |

| 19 | or/14–18 | 2,586,811 |

| 20 | 13 and 19 | 7,317 |

| 21 | oncology.hw. | 10,815 |

| 22 | (oncolog* or cancer).tw. | 713,898 |

| 23 | 21 or 22 | 716,348 |

| 24 | 20 and 23 | 427 |

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

None of the authors has any financial conflicts of interest to declare.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Astin JA, Reilly C, Perkins C, Child WL, on behalf of the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Breast cancer patients’ perspectives on and use of complementary and alternative medicine: a study by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4:157–69. doi: 10.2310/7200.2006.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL, Hislop TG, Herbert C. Levels of commitment: exploring complementary therapy use by women with breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:459–66. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eng J, Ramsum D, Verhoef M, Guns E, Davison J, Gallagher R. A population-based survey of complementary and alternative medicine use in men recently diagnosed with prostate cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003;2:212–16. doi: 10.1177/1534735403256207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molassiotis A, Fernadez–Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:655–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gansler T, Kaw C, Crammer C, Smith T. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng GE, Frenkel M, Cohen L, et al. on behalf of the Society for Integrative Oncology Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2009;7:85–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagar SM. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2009;7:83–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagar SM. Integrative oncology in North America. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4:27–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagar SM, Leis AM. Integrative oncology: a Canadian and international perspective. Curr Oncol. 2008;15(suppl 2):s71–3. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i0.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boon H, Verhoef M, O’Hara D, Findlay B, Majid N. Integrative health care: arriving at a working definition. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter ID, Khorsan R, Crawford C, Hsiao AF. Integrative health care under review: an emerging field. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:690–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg LB. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zappa SB, Cassileth BR. Complementary approaches to palliative oncology care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18:22–6. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassileth BR. The Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:585–8. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.50009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassileth BR, Vickers AJ. Massage therapy for symptom control: outcome study at a major cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassileth BR, Gubili J. The Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center. In: Cohen L, Markman M, editors. Integrative Oncology: Incorporating Complementary Medicine into Conventional Cancer Care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2008. pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.cam center profile: Integrative Medicine Service, Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Altern Ther Womens Health. 2003;5:40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng G. Integrative cancer care in a U.S. academic cancer centre: the Memorial Sloan–Kettering experience. Curr Oncol. 2008;15(suppl 2):s108.es68–71. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i0.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miner W. Training massage therapists to work in oncology. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2007;5:163–6. doi: 10.2310/7200.2007.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolbeault S, Holland JC. Twenty-five years of psychooncology in New York: a retrospective [French] Bull Cancer. 2008;95:419–24. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2008.0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zablocki E. Integrative care, mind–body methods aid cancer patients. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients. 2004:54–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Block KI, Block P, Gyllenhaal C. The role of optimal healing environments in patients undergoing cancer treatment: clinical research protocol guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(suppl 1):S157–70. doi: 10.1089/1075553042245791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Block KI. On models for integrative medical practice. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:309–12. doi: 10.1177/1534735407310180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charles L. Integration of complementary disciplines into the oncology clinic. Part vii. Integrating psychological services with medical treatment for patients with breast cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2000;24:280–90. doi: 10.1016/S0147-0272(00)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micozzi MS. Integrative medicine in contemporary health care: part ii. Integr Med. 2006;5:24–8. [Google Scholar]