Welsh poet Dylan Thomas postulated in his now-immortal work, Do not go gentle into that good night, that “old age should burn and rave at close of day.”

But as the incidence rate for suicide among senior citizens attests, illness, despair and even simple exhaustion take an inevitable toll, prompting a surprising number to look for an end to their days of perceived futility.

It’s a problem that’s often unrecognized and undertreated, and which will only become more common as the cohort of baby boomers transitions into seniorhood, experts say.

Some 398 men and 90 women aged 65 or older in Canada took their own lives in 2009, according to Statistics Canada (www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/hlth66a-eng.htm). Although the numbers of deaths by suicide was largest among middle-age men, the rate of suicide was highest among men age 85 to 89 at 30.6 per 100 000 Canadians, well above the national average for all age groups of 11.5.

Curiously, the suicide incidence rate slowly declined for all age cohorts over the past century except for postwar baby boomers, who have continued to exhibit higher rates as they age. According to one US study, that trend will continue as the boomers become seniors, particularly those who are unmarried and less educated (www.publichealthreports.org/issueopen.cfm?articleID=2514). The authors surmise that economic stresses, the rate of multiple chronic diseases and the high cost of health care are contributory factors to the ongoing increase.

What’s also likely is that the real extent of the incidence of senior suicide is probably understated and uncaptured by statistics, says Marnin Heisel, a scientist with the Lawson Health Research Institute of the London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Health Care London in Ontario.

By dint of time alone, seniors are more likely to have risk factors typically associated with suicide: a history of suicidal behaviour or thinking, social isolation and death of a friend or family member.

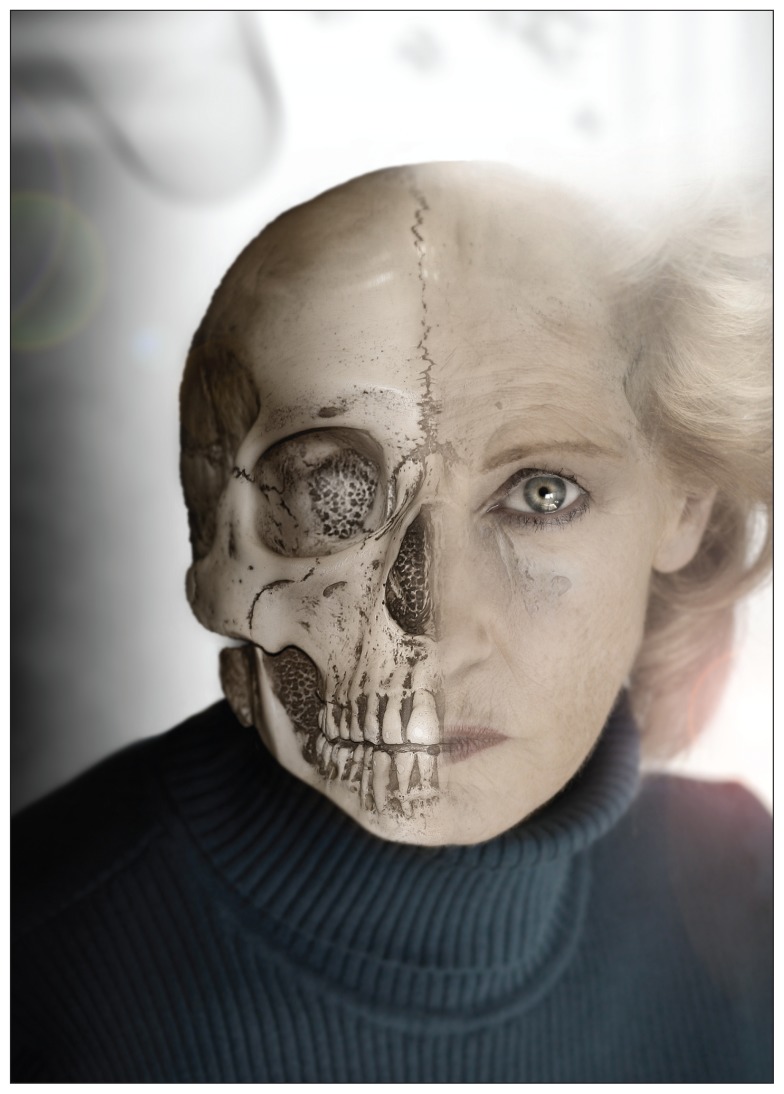

Image courtesy of © 2012 Thinkstock

Deaths by suicide are often overlooked because coroners have difficulty distinguishing between self-inflicted and natural or accidental death in equivocal cases, Heisel says. That’s true across the age spectrum but particularly so among the elderly, whose deaths can often be attributed to other causes, he adds. “Perhaps they forgot they had already taken their medication, didn’t quite understand how to take it, maybe they were confused.”

Equally problematic is that the problem of senior suicide is often overlooked by health professionals and even family and friends as there’s a false notion within society that mental health issues are just par for the course when it comes to the elderly, says Michael Price, manager of the Communities Addressing Suicide Together program, a Nova Scotia-based initiative of the Canadian Mental Health Association. “Feeling hopeless or purposelessness, or thinking a lot about death — those are all warning signs for suicide, but they’re also things we tie closely with the elderly,” he says. “We expect a level of depression because they’re losing loved ones and dealing with more chronic illnesses.”

There’s also a tendency to treat mental health problems within seniors with less alacrity, says Sharon Moore, associate professor at the Centre for Nursing and Health Studies of the Faculty of Health Disciplines at Athabasca University in Alberta.

“Some people say, well, people who reach the end of their lives have lived a good life so why bother,” Moore says. “Sometimes there’s this almost fatalistic attitude of why should we bother.”

By dint of time, alone, the elderly are also more likely to have risk factors typically associated with suicide: a history of suicidal behaviour or thinking, social isolation and death of a friend or family member. That can contribute to a loss of hope and increase the risk of suicide, Moore notes. “Lots of times what we see is not so much one particular event, but an accumulation of things that seem to contribute to that overall sense of despair — the feeling that nothing in life is worth living for.”

Other seniors simply have difficulty handling late-life transitions, such as forced retirements, particularly for men, who often lack a social network to fill the void, says Heisel.

But ageism is also a factor, he adds, noting that society often devalues the experience of seniors and relegates them to life’s sidelines. “As we age, if we’re raised in a culture that devalues older adults, then we get to a point where we devalue ourselves.”

Heisel says that there’s evidence that senior citizens who are contemplating suicide respond well to treatment. But the trick is identifying them, as seniors are less likely to acknowledge depressive symptoms or other health problems, he adds. As a consequence, they are less likely to reach out for help; “They may have more stigmatizing views of mental health care, and don’t see it as something that’s as reasonable a course of action as trying to deal with one’s problems on one’s own.”

Part of that is generational, says Kimberly Wilson, executive director of the Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. “I think right now we’re really in an era where mental health is coming out of the shadows, but perhaps for our current cohort of older adults, there still was a lot of stigma about mental illness and it may not be something they’re comfortable talking to their physicians about.”

There’s also a societal perception that it’s entirely normal for an elderly person to experience a certain degree of hopelessness and sadness, Price argues. “Right now society is accepting a lot of things as being a normal part of aging, suicide being one of them maybe, and we need to change that thinking. We’re all going to be seniors one day and we’re going to want those protections for ourselves if nothing else.”

Editor’s note: First of a two-part series.

Next: Senior suicide: The tricky task of treatment