Abstract

Background and Purpose

Brain microvascular disorders, including cerebral microscopic hemorrhage, have high prevalence but few treatment options. To develop new strategies for these disorders, we analyzed effects of several phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors on human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBEC).

Methods

We modified barrier properties and response to histamine of HBEC using cilostazol (PDE-3 inhibitor), rolipram (PDE-4 inhibitor), and dipyridamole (non-specific PDE inhibitor).

Results

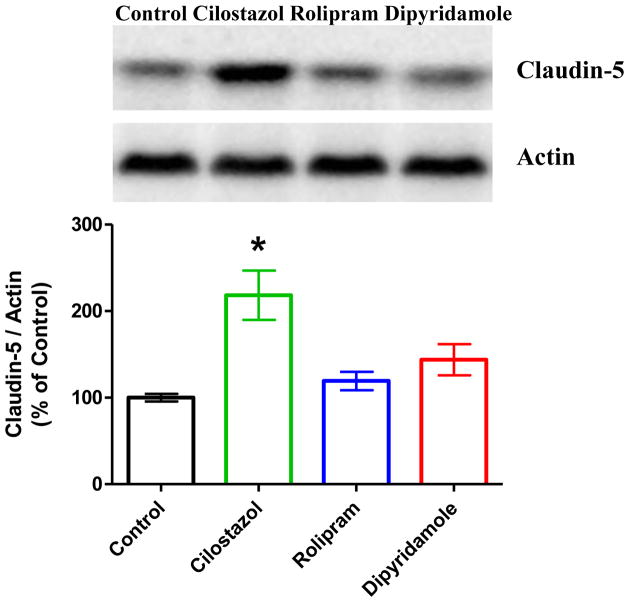

Cilostazol and dipyridamole altered distribution of endothelial F-actin. Cilostazol increased expression of tight junction protein claudin-5 by 118 % compared to control (p<.001). Permeability to albumin was decreased by cilostazol (21% vs control, p<.05), and permeability to dextran (70Kd) was decreased by both cilostazol (37% vs control, p<.001) and dipyridamole (44% vs control, p<.0001). Cilostazol increased trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) after 12 hours by 111% compared to control (p<.0001). Protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitors H89 and KT5720 attenuated the TEER increase by cilostazol. Transient increased permeability in response to histamine was significantly mitigated by cilostazol, but not other PDE inhibitors.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate distinctive effects of cilostazol and other PDE inhibitors on HBEC, including enhanced barrier characteristics and mitigation of response to histamine. PKA-mediated effects of cilostazol were prominent in this model. These in vitro findings are consistent with therapeutic potential of PDE inhibitors in human brain microvascular disorders.

Keywords: cell culture, endothelial, microcirculation, phosphodiesterase, histamine

Introduction

Microvascular disorders of the brain are increasingly recognized as a major public health issue. These disorders are part of the spectrum of cerebrovascular disease ranging from clinical ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke to the largely subclinical cerebral white matter disease (CWMD) [1–4]. Both CWMD and cerebral microscopic hemorrhage are widely prevalent in the aging population and include a substantial capillary component [5–7]. Currently there is no specific treatment for these disorders. A recently proposed model of cerebral microscopic hemorrhage suggested that transient loss of endothelial barrier function might be an underlying process [5].

Effective stroke prevention should consider both thrombosis (pathological generation of clot) and hemostasis (maintenance of blood within the vasculature). Current ischemic stroke prevention therapy is typically anti-thrombotic, with little concern for hemostasis. This attitude is becoming increasingly untenable given the high prevalence of hemorrhagic phenomena with ischemic stroke, the coexistence of which has been termed “mixed cerebrovascular disease” [4, 8].

Cilostazol has been evaluated in ischemic stroke prevention clinical trials [9–11] and relies on phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibition as its principal mechanism [12]. Cyclic nucleotide PDEs are enzymes that regulate the cellular levels of second messengers cAMP and cGMP by controlling their degradation [13–15]. Cilostazol is a well-known PDE-3 inhibitor [12] while dipyridamole, another ischemic stroke prevention agent [16, 17], is a nonspecific PDE inhibitor [13]. While the platelet effects of these agents are well-known, their effectiveness in protecting and enhancing endothelial barrier function has received limited attention. Other PDE inhibitors (eg, PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil) have been shown to improve functional recovery in experimental stroke [18].

The current study is designed to assist development of new therapeutic strategies for brain microvascular disorders, with particular reference to the population of patients with coexisting ischemic and hemorrhagic processes. We studied the effectiveness of these PDE inhibitors (cilostazol and dipyridamole) along with rolipram (a PDE-4 inhibitor)[13] in modulating endothelial barrier properties in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture preparations

HBEC (Applied Cell Biology Research Institute, Kirkland, WA) were grown on tissue culture plates pre-coated with attachment factor (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Endothelial cells demonstrated typical cobblestone morphology and immunoreactivity for von Willebrand factor (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA) and uptake of acetylated low density lipoprotein labeled with 1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine perchlorate (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA). Cell passaging was performed using passage reagent group (Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA), and cells from passages 6–10 were used for experiments.

HBEC were maintained in Medium 131 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 5% microvascular growth supplement (MVGS) (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA); at the beginning of experiments, 50μM forskolin [19] (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to all cell culture preparations. Rolipram (AG Scientific, CA), cilostazol (Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Japan), and dipyridamole (Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany), dissolved in DMSO, were added to cell culture preparations at concentrations of 10, 20 and/or 30 μM. PDE7 inhibitor BRL50481 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 1, 10 and 30 μM. PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 30 μM. DMSO concentrations were the same throughout all cell culture groups (0.1%). We changed medium at intervals of 48 hours, and cells were treated up to 3 days to enhance barrier function [20].

PKA inhibitors, 10 μM H89 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) [21–23] and 1 μM KT5720 [19] (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and PKG inhibitor, 1μM KT5823 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) [24, 25], were initially dissolved in distilled water (H89) or in DMSO (the latter two). Cells were pretreated with H89, KT5720, or KT5823 for 0.5–1 hour before addition of PDE inhibitors. BRL50481 was added in the same way as cilostazol. 8-(4-Chlorophenylthio)-2'-O-methyl-cAMP (BIOLOG Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany) was dissolved in DMSO and used at 10 μM [26, 27]. Histamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 200 μg/ml working concentration. Mock treatment used vehicle (PBS diluted in M131 medium) without histamine. Histamine was added after 3 days of treatment with PDE inhibitors.

Measurement of Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER)

TEER across the HBEC monolayer was measured using Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) system Model 1600R (Applied BioPhysics, Troy, NY). Cells were grown on ECIS arrays (8W10E), with each well containing ten gold microelectrodes. Experiments were performed after the cells reached confluence (confirmed by stabilized TEER at baseline) with basal TEER values over 1000 Ω. The long-term resistance increase was monitored with the multi-frequency option (62.5, 125, 250, 400, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 8000, 16000, 32000, and 64000 Hz). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, data were displayed at 400 Hz (corresponding to establishment of cell - cell junctions). Histamine-induced decline was also measured at 400Hz. Resistance values of empty wells were measured and subtracted from TEER data. TEER at representative time points from three independent experiments were pooled and plotted against time. ECIS data were adjusted (normalized) to control.

Western blot and cAMP studies

Cells were collected in RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer with Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein was mixed with Novex Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer and Reducing Agent (both from Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) before loading to 10% polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subject to electrophoresis (75 Volts). Protein was transferred to PVDF (Polyvinylidene Difluoride) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) at 30 volts at 4°C overnight. Membrane was blocked in 5% milk for 1 hour at room temperature, and later incubated with mouse anti-claudin-5 monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). After incubation with primary antibody, membrane was washed with TBST (1% Tween 20) and then incubated with secondary antibody: goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Membrane was washed 3 times with TBST, 10 minutes each. Membrane was incubated in SuperSignal West Pico Chemilumin (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 5 minutes before imaging. Membrane was stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and re-probed for actin with anti-actin goat polyclonal IgG and donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP (both Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Images were quantified using ImageJ (NIH). Intracellular levels of cAMP were measured by enzyme immunoassay (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to instructions from the manufacturer.

F-actin staining

F-actin was stained with rhodamine phalloidin (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO). Briefly, cells were quickly and gently washed with PBS for 30 seconds and immediately fixed with 10% (v/v) formaldehyde and 3% methanol for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then (1) permeabalized with 0.5 % Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, (2) incubated with rhodamine phalloidin for 30 min in the dark, (3) incubated with DAPI (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for 10 min in the dark. Images were taken with a fluorescent microscope and Olympus Camera.

Permeability Assay

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled bovine serum albumin (BSA; Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) stock solution concentration was 5 mg/ml. FITC-labeled dextran (molecular size: 70kDa, Invitrogen, Carlsbad,CA) stock solution was 50 mg/ml. HBECs were cultured on 12 mm diameter transwell insert (pore size 0.4 μm) (Corning, Lowell, MA) and treated for 3 days total. Prior to permeability assay, stock solution was diluted 100 times with M131 medium and added to the upper chambers. Upper chamber was sampled at the beginning; bottom chamber was sampled periodically (15 minutes e.g.) for at least 3 consecutive time points. Fluorescence intensity was measured using Chameleon Mikrowin-2000 microplate fluorescent reader (Bioscan, Washington, DC). Permeability coefficient (P, mm/s) was calculated using the following equation: P= [V/(A×C0)] × [dC/dt], where V is the receiver volume (the volume of bottom chamber), A is the surface area of the endothelial monolayer, C0 is the concentration of the donor solution (the initial concentration of the upper chamber), and dC/dt is the rate of diffusion across the monolayer [28]. Permeability coefficient of endothelial cell monolayer (Pe) was calculated using the following equation: , where Pf is the permeability coefficient of the transwell membrane without cells [29].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance with Tukey’s tests for individual comparisons of groups. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

F-actin staining showed cilostazol and dipyridamole (30μM) modified actin cytoskeleton distribution. Both cilostazol and dipyridamole induced more concentrated actin in the central perinuclear region (Figure 1). Moreover, cilostazol induced F-actin mesh that was more extensive and uniformly distributed throughout cell. Dipyridamole induced F-actin distribution that concentrated in the cell periphery (cortical actin).

Figure 1.

Phalloidin rhodamine staining (200X magnification) of F-actin of human brain microvascular endothelial cells (control) (A), and microvascular endothelial cells treated with cilostazol (B), rolipram (C), and dipyridamole (D). Cilostazol and dipyridamole treatment produced more pronounced actin in nuclear region (shown with vertical arrow); dipyridamole also increased cortical actin (shown with horizontal arrow). All PDE inhibitors used at 30 μM. Scale bar is 50 uM. A representative image is shown for each treatment.

Protein immunoblotting studies demonstrated that after three days cilostazol (30μM) increased tight junction protein claudin-5 expression by 118% (p<.01 vs control), while rolipram and dipyridamole (30μM) had no effect (Figure 2). Permeability studies demonstrated permeability to albumin and dextran of control was 1.1±0.2 × 10−6 cm/s and 3.8±0.5 × 10−6 cm/s, respectively. Cilostazol (30μM) decreased endothelial permeability to both albumin (21% less than control, p<.05) (Figure 3A) and dextran (37% less than control, p<.001). Dipyridamole (30μM) also reduced dextran permeability (44% less than control, p<.001) (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Effect of PDE inhibitors (30μM) on change in tight junction protein claudin-5 expression. Cilostazol significantly increased claudin-5 expression. Signal intensity ratio between of claudin-5 and actin was normalized to control. Pooled results from three independent experiments. Values represent mean; error bars represent standard error (*p<.05 vs control).

Figure 3.

Effect of PDE inhibitors (30μM) on endothelial permeability to albumin (trans-cellular permeability marker) and on dextran (para-celluar permeability marker). Permeability to albumin was significantly decreased by cilostazol (A) while permeability to dextran was significantly decreased by both cilostazol and dipyridamole (B). Data were pooled from three independent experiments and normalized to control. Values represent mean; error bars represent standard error (*p<.05 vs control).

After 2 hour treatment, cilostazol (30 μM) significantly increased TEER compared to control. After 12 hours, cilostazol increased TEER by 111% compared to control (p<.0001). Rolipram and dipyridamole did not significantly increase TEER (Figure 4A). Protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitors H89 (Figure 4B) and KT5720 (Figure 4C) substantially attenuated elevated TEER induced by cilostazol. However, PKG inhibitor KT5823 did not modify increased resistance induced by cilostazol, and Epac activator 8-(4-Chlorophenylthio)-2'-O-methyl-cAMP (10 uM) did not significantly increase TEER (data not shown). Use of PDE7 inhibitor BRL50481 (1, 10, and 30 μM) did not significantly modify TEER (data not shown). Cilostamide (30 μM), another PDE3 inhibitor, also increased TEER (25±9%, 29±8%, 30±9%, 29±9%, 30±11%, 30±12%, and 29±13% increase at 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 hours after treatment, respectively; p<.05 vs control in all cases, pooled data of three independent experiments performed in triplicate). Levels of intracellular cAMP were similar for cilostazol-, rolipram-, and dipyridamole-treated cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of PDE inhibitors on trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER). (A) Cilostazol most potently and persistently increased TEER measured after 1 hour. Protein kinase A inhibitors H89 (B) and KT5720 (C) attenuated TEER increase induced by cilostazol at 1 hour after treatment. For A, data were pooled from three independent experiments and normalized to control at time 0; for B and C, data were pooled from three independent experiments and normalized to control. Values represent mean; error bars represent standard error (*p<.05 vs control at each corresponding time point).

Histamine (200 μg/ml) induced a transient decline in TEER, with maximum decline between 1 and 2 minutes in all treatment and control groups (Figure 5A). Compared to control, HBEC treated with cilostazol maintained an overall higher TEER both before and after histamine treatment (Figure 5A). Mock treatment (vehicle without histamine) produced no decline in TEER (data not shown). After treatment for 3 days, cilostazol (30 μM), but not dipyridamole or rolipram, increased TEER (32% higher than control, p<.0001) (Figure 5B). When comparing the lowest point (nadir) of TEER during histamine treatment, cilostazol produced a dose-dependent increase, with 30 μM increasing nadir by 40% compared to the nadir of control (p<.0001) (Figure 5B). Percent changes in TEER following treatment with 30 uM cilostazol reflect decline from 3224±380 ohms (p<.001 vs control) to 2759±312 ohms (p<.001 vs control, pooled data of three independent experiments performed in triplicate).

Figure 5.

Pretreatment for 3 days with PDE inhibitors modified the histamine-induced decline in TEER. Histamine (200 μg/ml) induced a transient decline in TEER (A). Both before and after histamine (including at TEER nadir), only 30 μM cilostazol produced higher TEER than control (B). Data were pooled from three independent experiments and normalized to control at time 0. Values represent mean; error bars represent standard error (comparing TEER before histamine:*p<.05 vs control; comparing nadirs: † p<.05 vs control).

Discussion

We analyzed effects of cilostazol, dipyridamole, and rolipram, on barrier properties of HBEC in vitro. Cilostazol and dipyridamole decreased dextran (para-cellular) permeability and modified actin cytoskeleton distribution. Cilostazol decreased albumin (trans-cellular) permeability and increased tight junction protein claudin-5 expression. Cilostazol most potently and persistently increased TEER (mediated by PKA), producing an overall higher TEER throughout the course of response to histamine. These findings demonstrate distinctive effects of cilostazol and other PDE inhibitors on modulating endothelial barrier properties.

It is well-established that cAMP elevating agents increase TEER [30, 31]. However, the duration of increase has been largely limited. In one study, cAMP-dependent increase in TEER induced by adenosine lasted for a maximum of only 2 hours, after which the resistance declined dramatically [32]. Another study showed that TEER induced by forskolin and rolipram increased within one hour range [31]. Our study demonstrated treatment with rolipram increased TEER (compared to baseline), but TEER began to decline at approximately 2 hours. In contrast, treatment with cilostazol produced a sustained increase in TEER lasting for at least 12 hours. This suggests a mechanism different from that of rolipram may be involved in mediating the enhancement of barrier functions induced by cilostazol.

The effects of cilostazol in this study are likely mediated via PDE3. Cilostazol is a potent PDE3 inhibitor [12] and PDE3 is known to be expressed by HBEC [33]. Moreover, another PDE3 inhibitor (cilostamide) increased TEER in the current study. However, cilostazol may also inhibit PDE5, PDE7 (IC50 of 4.4 and 21.4 μM, respectively) [34], and adenosine uptake (IC50 of 5–10 μM) [35]. In our study, cilostazol was most effective at 30 μM, higher than its IC50 for PDE3 (0.20 μM for PDE3A and 0.38 μM for PDE3B in human recombinant phosphodiesterases [36]; 1 to 10 μM in intact cells or hearts [35]). At this concentration, cilostazol may inhibit other targets. It is unlikely that cGMP dependent PDE5[13] was involved, because cGMP inhibitor KT5823 did not modify effects of cilostazol; moreover, cilostazol has been shown to increase cAMP, but not cGMP levels in platelets [37]. It is also unlikely that inhibition of adenosine uptake was the mechanism, since dipyridamole (which also inhibits adenosine uptake [38]) did not increase TEER. It is also unlikely PDE7 mediated these effects, because PDE7 inhibitor BRL50481 did not increase TEER, despite known presence of PDE7 in HBEC and in rat brain[13].

Elevation of intracellular cAMP is known to induce barrier formation in cultured brain endothelial cells [29, 39, 40], and treatment of brain endothelial cells with PDE inhibitors strengthens monolayer integrity [41, 42]. More specifically, Ishiguro et al showed that cilostazol protected brain endothelial cells against in vitro ischemia (OGD) and enhanced VE-cadherin via cAMP/PKA [43]. Ishiguro et al later showed blood-brain barrier protective effects of cilostazol in an in vivo model of experimental stroke, and also showed evidence of endothelial cell protection by cilostazol in vitro [44]. Easton and Dovorini-Zis showed that rolipram (at 100uM) blocked histamine-induced p-selectin expression by brain endothelial cells [45]. Folcik et al showed that rolipram improved blood-brain barrier permeability in vivo during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [46]. Guo et al showed that dipyridamole protected brain endothelial cells against OGD-induced MMP-9 release [47]. Mackic et al examined the response of brain endothelial cells to Cereport, a bradykinin B2 agonist, showing that increased permeability was inhibited by rolipram and increased by zaniprast; the latter was attributed to cGMP-mediated effects [48]. The study of Mackic et al is particularly relevant to the current investigation [48]. We have previously shown that rolipram induces only minor changes in permeability of brain endothelial cell monolayer treated with forskolin [49]. Moreover, dipyridamole is known to have cGMP-mediated effects [38]. Therefore, our findings for rolipram (no effects on response to histamine) and dipyridamole (increased response to histamine) appear to be consistent with the work of Mackic et al [48].

Our results showed PKA inhibitors (H89 and KT5720) strongly attenuated the increased TEER induced by cilostazol. This suggests cilostazol increases TEER through PKA-dependent pathways. H89 has been found also to inhibit cilostazol-induced vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) phosphorylation in platelets and platelet aggregation [37]. In a recent study cilostazol activated PKA and Epac1 pathways, leading to increased integrin expression and endothelial adhesion [50]. We used 8-(4-Chlorophenylthio)-2'-O-methyl-cAMP, a potent, specific and membrane-permeant activator of Epac, to see if Epac activation would lead to similar results observed with cilostazol. We have previously shown that this Epac activator reduced tPA expression in our cell culture system [51]. However, this Epac activator was unable to increase TEER, suggesting Epac activation was not responsible for cilostazol mediated effects. These findings suggest PKA activation is regularly involved in those cilostazol-mediated effects. Since PDE3 activates and is a substrate for PKA [52] and function of PDE3 is dependent on PKA and actin cytoskeleton [53], the effect of cilostazol in our study is likely mediated by PDE3. We also measured cAMP levels and found comparable levels for all three PDE inhibitors, suggesting that the difference in efficacy may not be related to overall cAMP-elevating potential. This is consistent with the understanding that cAMP signaling is compartmentalized, regulated both spatially and temporally, and that global measurements of cAMP may not represent the complexity of the cAMP signals [53, 54]. Different PDE inhibitors inherently differ from each other in their specificity to PDE targets, generating unique cAMP patterns and alterations of signaling pathways.

PKA plays an important role in regulating endothelial barrier properties via cytoskeletal rearrangement [55], and endothelial cytoskeleton is essential for endothelial permeability [23, 56]. We observed that dipyridamole treatment produced more pronounced cortical actin, which is necessary for maintenance of endothelial barrier integrity [56]. Consistently, dipyridamole improved barrier function in terms of decreased permeability to dextran (para-ceullar permeability). Cilostazol improved barrier function, with decreased permeability to both albumin and dextran (trans-cellular and para-cellular permeability, respectively [29, 57]) and increased TEER. This may be due to enhanced tight junctions, as evidenced by upregulated claudin-5 expression. Claudin-5 is a key tight junction protein linked to barrier properties in vitro and in vivo and is the most prominent tight junction protein induced by cAMP in brain endothelial cells [58, 59]. Cilostazol has been shown to reduce brain edema and hemorrhagic transformation in vivo by inhibiting decreased expression of claudin-5 [44]. Moreover, cilostazol has been shown to protect the blood-brain barrier in vitro by increasing VE-cadherin expression in brain endothelial cells via cAMP/PKA-dependent pathways [43].

We observed mitigation of histamine-mediated effects on endothelial resistance by cilostazol. Histamine, a mediator of inflammation, is released by mast cells and circulating basophils, resulting in increased endothelial permeability and vascular leakage [60, 61]. Histamine induces a rapid and transient increase in barrier permeability, as shown by a transient decrease in TEER [62, 63]. The precise pathway by which histamine increases permeability is incompletely understood. Potential mechanisms include calcium mobilization and activation PKC, myosin light chain phosphorylation by myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and actin-myosin contraction, and alterations in actin cytoskeleton [60, 64–66]. Cilostazol may interfere with the effects on histamine on multiple levels. Cilostazol inhibits the redistribution of the actin cytoskeleton and junctional proteins under hypoxia/reoxygenation conditions [23]. It also inhibits calcium mobilization, which attenuates the histamine-induced contraction in smooth muscle of the peripheral middle cerebral artery in rabbits [67]. In the current study, increased TEER induced by cilostazol was maintained after histamine so that absolute TEER level after decline remained higher than the baseline control level.

The implications of our findings are limited by the in vitro nature of the study and the characteristics of our in vitro model. Therefore, extrapolations of our findings to the in vivo setting are of necessity limited and must be done with caution. Specifically, we utilized passaged HBEC, with forskolin treatment to improve basal barrier properties [22, 68]. In addition, the concentration of cilostazol in our system (30 μM) may be higher than that found in clinical use. After oral administration, concentration of cilostazol has been shown to be 2–10 μM in plasma but may be higher in certain tissues because of lipophilicity [69, 70]. Nonetheless, 30 μM cilostazol has been used in prior studies [37, 69, 71]. Our study is consistent with the protective effects against ischemic-reperfusion injury in mouse cerebrum [72] as well as therapeutic efficacy of cilostazol in stroke clinical trials [9–11]. It is noteworthy that use of cilostazol was associated with fewer ischemic strokes and hemorrhagic events than aspirin in the stroke clinical trials [11], suggesting a beneficial impact on both thrombosis and hemostasis. Rolipram was used at 10 μM in vivo and in vitro to increase intracellular cAMP levels [73]. Dipyridamole used at 5 uM significantly attenuated ICAM-1 and MMP-9 levels after inflammatory challenge [47] and has been used at concentration of 100 uM in vitro [37] .

In conclusion, cilostazol and other PDE inhibitors modified multiple aspects of brain endothelial barrier properties in vitro, including TEER, permeability, tight junction protein expression, and actin cytoskeleton. In addition, cilostazol modified brain endothelial barrier response to histamine injury, suggesting a protective effect on vascular integrity. These in vitro findings are consistent with a potential therapeutic role for PDE inhibitors in the treatment of cerebral microvascular diseases.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of findings.

Acknowledgments

We thank UC Irvine undergraduate student Ketan Chopra for his assistance.

Sources of Funding

Supported by NIH RO1 NS20989 and a grant from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company.

Footnotes

Disclosure(s)

Dr. Fisher has received support from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co (research grant, honoraria) and from Boehringer-Ingelheim (research grant, speakers’ bureau, honoraria).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Farrall AJ, Wardlaw JM. Blood-brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease--systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(3):337–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Zoppo GJ. The neurovascular unit in the setting of stroke. J Intern Med. 2010;267(2):156–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeevi N, Pachter J, McCullough LD, Wolfson L, Kuchel GA. The blood-brain barrier: geriatric relevance of a critical brain-body interface. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1749–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher M. The challenge of mixed cerebrovascular disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher M, French S, Ji P, Kim RC. Cerebral microbleeds in the elderly: a pathological analysis. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2782–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen KM, Kocsi Z, Stone J. Pericapillary haem-rich deposits: evidence for microhaemorrhages in aging human cerebral cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(12):1656–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young VG, Halliday GM, Kril JJ. Neuropathologic correlates of white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 2008;71(11):804–11. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319691.50117.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernooij MW, Haag MD, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Stricker BH, et al. Use of antithrombotic drugs and the presence of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(6):714–20. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto M. Cilostazol in secondary prevention of stroke: impact of the Cilostazol Stroke Prevention Study. Atheroscler Suppl. 2005;6(4):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Park SY, Shin HK, Kim CD, Lee WS, Hong KW. Protective effects of cilostazol against transient focal cerebral ischemia and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion injury. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(2):143–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2008.00042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinohara Y, Katayama Y, Uchiyama S, Yamaguchi T, Handa S, Matsuoka K, et al. Cilostazol for prevention of secondary stroke (CSPS 2): an aspirin-controlled, double-blind, randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(10):959–68. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson PE, Manganiello V, Degerman E. Re-discovering PDE3 inhibitors--new opportunities for a long neglected target. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7(4):421–36. doi: 10.2174/156802607779941224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lugnier C. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE) superfamily: a new target for the development of specific therapeutic agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109(3):366–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackman BE, Horner K, Heidmann J, Wang D, Richter W, Rich TC, et al. PDE4D and PDE4B function in distinct subcellular compartments in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conti M, Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener HC. Dipyridamole trials in stroke prevention. Neurology. 1998;51(3 Suppl 3):S17–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3_suppl_3.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.d'Esterre CD, Lee TY. Effect of dipyridamole during acute stroke: exploring antithrombosis and neuroprotective benefits. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207:71–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Zhang Z, Zhang RL, Cui Y, LaPointe MC, Silver B, et al. Tadalafil, a long-acting type 5 phosphodiesterase isoenzyme inhibitor, improves neurological functional recovery in a rat model of embolic stroke. Brain Res. 2006;1118(1):192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y-Y, Martin KC, Kandel ER. Both Protein Kinase A and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Are Required in the Amygdala for the Macromolecular Synthesis-Dependent Late Phase of Long-Term Potentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20(17):6317–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06317.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Z, Hofman FM, Zlokovic BV. A simple method for isolation and characterization of mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;130(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoque KM, Woodward OM, van Rossum DB, Zachos NC, Chen L, Leung GP, et al. Epac1 mediates protein kinase A-independent mechanism of forskolin-activated intestinal chloride secretion. J Gen Physiol. 2010;135(1):43–58. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuhara S, Sakurai A, Sano H, Yamagishi A, Somekawa S, Takakura N, et al. Cyclic AMP potentiates vascular endothelial cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact to enhance endothelial barrier function through an Epac-Rap1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(1):136–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.136-146.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torii H, Kubota H, Ishihara H, Suzuki M. Cilostazol inhibits the redistribution of the actin cytoskeleton and junctional proteins on the blood-brain barrier under hypoxia/reoxygenation. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(2):104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen W, Hao J, Feng Z, Tian C, Chen W, Packer L, et al. Lipoamide or lipoic acid stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via the endothelial NO synthase-cGMP-protein kinase G signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162(5):1213–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korkmaz B, Buharalioglu K, Sahan-Firat S, Cuez T, Tuncay Demiryurek A, Tunctan B. Activation of MEK1/ERK1/2/iNOS/sGC/PKG pathway associated with peroxynitrite formation contributes to hypotension and vascular hyporeactivity in endotoxemic rats. Nitric Oxide. 2011;24(3):160–72. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vliem MJ, Ponsioen B, Schwede F, Pannekoek WJ, Riedl J, Kooistra MR, et al. 8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP-AM: an improved Epac-selective cAMP analogue. Chembiochem. 2008;9(13):2052–4. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastor-Soler NM, Hallows KR, Smolak C, Gong F, Brown D, Breton S. Alkaline pH- and cAMP-induced V-ATPase membrane accumulation is mediated by protein kinase A in epididymal clear cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294(2):C488–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00537.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eddy EP, Maleef BE, Hart TK, Smith PL. In vitro models to predict blood-brain barrier permeability. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;23(1–3):185–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deli MA, Abraham CS, Kataoka Y, Niwa M. Permeability studies on in vitro blood-brain barrier models: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25(1):59–127. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waschke J, Drenckhahn D, Adamson RH, Barth H, Curry FE. cAMP protects endothelial barrier functions by preventing Rac-1 inhibition. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2004;287(6):H2427–H33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00556.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumer Y, Drenckhahn D, Waschke J. cAMP induced Rac 1-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization in microvascular endothelium. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129(6):765–78. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0422-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umapathy NS, Fan Z, Zemskov EA, Alieva IB, Black SM, Verin AD. Molecular mechanisms involved in adenosine-induced endothelial cell barrier enhancement. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schankin CJ, Kruse LS, Reinisch VM, Jungmann S, Kristensen JC, Grau S, et al. Nitric oxide-induced changes in endothelial expression of phosphodiesterases 2, 3, and 5. Headache. 2010;50(3):431–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sudo T, Tachibana K, Toga K, Tochizawa S, Inoue Y, Kimura Y, et al. Potent effects of novel anti-platelet aggregatory cilostamide analogues on recombinant cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isozyme activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59(4):347–56. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, Shakur Y, Yoshitake M, Kambayashi Ji J. Cilostazol (pletal): a dual inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase type 3 and adenosine uptake. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2001;19(4):369–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2001.tb00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birk S, Edvinsson L, Olesen J, Kruuse C. Analysis of the effects of phosphodiesterase type 3 and 4 inhibitors in cerebral arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;489(1–2):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sudo T, Ito H, Kimura Y. Phosphorylation of the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) by the anti-platelet drug, cilostazol, in platelets. Platelets. 2003;14(6):381–90. doi: 10.1080/09537100310001598819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HH, Liao JK. Translational therapeutics of dipyridamole. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(3):s39–42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin LL, Hall DE, Porter S, Barbu K, Cannon C, Horner HC, et al. A cell culture model of the blood-brain barrier. J Cell Biol. 1991;115(6):1725–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toth A, Veszelka S, Nakagawa S, Niwa M, Deli MA. Patented in vitro blood-brain barrier models in CNS drug discovery. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2011;6(2):107–18. doi: 10.2174/157488911795933910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raub TJ. Signal transduction and glial cell modulation of cultured brain microvessel endothelial cell tight junctions. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2 Pt 1):C495–503. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zenker D, Begley D, Bratzke H, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, von Briesen H. Human blood-derived macrophages enhance barrier function of cultured primary bovine and human brain capillary endothelial cells. J Physiol. 2003;551(Pt 3):1023–32. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishiguro M, Suzuki Y, Mishiro K, Kakino M, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, et al. Blockade of phosphodiesterase-III protects against oxygen-glucose deprivation in endothelial cells by upregulation of VE-cadherin. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2011;8(2):86–94. doi: 10.2174/156720211795495385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishiguro M, Mishiro K, Fujiwara Y, Chen H, Izuta H, Tsuruma K, et al. Phosphodiesterase-III inhibitor prevents hemorrhagic transformation induced by focal cerebral ischemia in mice treated with tPA. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Easton AS, Dorovini-Zis K. The kinetics, function, and regulation of P-selectin expressed by human brain microvessel endothelial cells in primary culture. Microvasc Res. 2001;62(3):335–45. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Folcik VA, Smith T, O'Bryant S, Kawczak JA, Zhu B, Sakurai H, et al. Treatment with BBB022A or rolipram stabilizes the blood-brain barrier in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: an additional mechanism for the therapeutic effect of type IV phosphodiesterase inhibitors. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;97(1–2):119–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo S, Stins M, Ning M, Lo EH. Amelioration of inflammation and cytotoxicity by dipyridamole in brain endothelial cells. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30(3):290–6. doi: 10.1159/000319072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackic JB, Stins M, Jovanovic S, Kim KS, Bartus RT, Zlokovic BV. Cereport (RMP-7) increases the permeability of human brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayers. Pharm Res. 1999;16(9):1360–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1018938722768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang F, Liu S, Wang SJ, Yu C, Paganini-Hill A, Fisher MJ. Tissue plasminogen activator expression and barrier properties of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28(4):631–8. doi: 10.1159/000335785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee DH, Lee HR, Shin HK, Park SY, Hong KW, Kim EK, et al. Cilostazol enhances integrin-dependent homing of progenitor cells by activation of camp-dependent protein kinase in synergy with Epac1. J Neurosci Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jnr.22558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang F, Liu S, Yu C, Wang SJ, Paganini-Hill A, Fisher MJ. PDE4 Regulates Tissue Plasminogen Activator Expression of Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Thromb Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Conti M. Phosphodiesterases and cyclic nucleotide signaling in endocrine cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(9):1317–27. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.9.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Penmatsa H, Zhang W, Yarlagadda S, Li C, Conoley VG, Yue J, et al. Compartmentalized cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate at the plasma membrane clusters PDE3A and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator into microdomains. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(6):1097–110. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper DM. Compartmentalization of adenylate cyclase and cAMP signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 6):1319–22. doi: 10.1042/BST0331319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu F, Verin AD, Borbiev T, Garcia JG. Role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A activity in endothelial cell cytoskeleton rearrangement. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280(6):L1309–17. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasain N, Stevens T. The actin cytoskeleton in endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvasc Res. 2009;77(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(1):41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishizaki T, Chiba H, Kojima T, Fujibe M, Soma T, Miyajima H, et al. Cyclic AMP induces phosphorylation of claudin-5 immunoprecipitates and expression of claudin-5 gene in blood-brain-barrier endothelial cells via protein kinase A-dependent and -independent pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290(2):275–88. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perrière N, Yousif S, Cazaubon S, Chaverot N, Bourasset F, Cisternino S, et al. A functional in vitro model of rat blood-brain barrier for molecular analysis of efflux transporters. Brain Research. 2007;1150:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tiruppathi C, Minshall RD, Paria BC, Vogel SM, Malik AB. Role of Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39(4–5):173–85. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones BL, Kearns GL. Histamine: New Thoughts About a Familiar Mediator. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abbott NJ. Inflammatory mediators and modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20(2):131–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1007074420772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Draijer R, Vermeer MA, van Hinsbergh VW. Transient and prolonged increase in endothelial permeability induced by histamine and thrombin: role of protein kinases, calcium, and RhoA. Circ Res. 1998;83(11):1115–23. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.11.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srinivas SP, Satpathy M, Guo Y, Anandan V. Histamine-Induced Phosphorylation of the Regulatory Light Chain of Myosin II Disrupts the Barrier Integrity of Corneal Endothelial Cells. Investigative Ophthalmology Visual Science. 2006;47(9):4011–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buckland KF, Williams TJ, Conroy DM. Histamine induces cytoskeletal changes in human eosinophils via the H(4) receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140(6):1117–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo Y, Ramachandran C, Satpathy M, Srinivas SP. Histamine-induced myosin light chain phosphorylation breaks down the barrier integrity of cultured corneal epithelial cells. Pharm Res. 2007;24(10):1824–33. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shiraishi Y, Kanmura Y, Itoh T. Effect of cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase type III inhibitor, on histamine-induced increase in [Ca2+]i and force in middle cerebral artery of the rabbit. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123(5):869–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolburg H, Neuhaus J, Kniesel U, Krauss B, Schmid E, Ocalan M, et al. Modulation of tight junction structure in blood-brain barrier endothelial cells. Effects of tissue culture, second messengers and cocultured astrocytes. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(5):1347–57. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.5.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ota H, Eto M, Kano MR, Ogawa S, Iijima K, Akishita M, et al. Cilostazol inhibits oxidative stress-induced premature senescence via upregulation of Sirt1 in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(9):1634–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.164368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schror K. The pharmacology of cilostazol. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2002;4 (Suppl 2):S14–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2002.0040s2s14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hashimoto Activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by cilostazol via a cAMP/protein kinase A-and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent mechanism. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189(2):350. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morikawa T, Hattori K, Kajimura M, Suematsu M. The effects of cilostazol on tissue oxygenation upon an ischemic-reperfusion injury in the mouse cerebrum. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;662:89–94. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1241-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schlegel N, Baumer Y, Drenckhahn D, Waschke J. Lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial barrier breakdown is cyclic adenosine monophosphate dependent in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1735–43. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819deb6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]