Abstract

EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) is important for EBV contributions to B cell transformation and many EBV-associated malignancies, as well as EBV-mediated exacerbation of autoimmunity. LMP1 functionally mimics tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily member CD40, but LMP1 signals and downstream effects are amplified and sustained compared to CD40. CD40 and LMP1 both utilize TNFR-associated factor (TRAF) adaptor proteins, but in distinct ways. LMP1 functions require TRAFs 3, 5, and 6, which interact with LMP1. However, TRAFs can also contribute to signaling in the absence of direct interactions with cell surface receptors, so we investigated whether their roles in LMP1 in vivo functions require direct association. We show here that the LMP1 TRAF binding site was required for LMP1-mediated autoantibody production, the germinal center response to immunization, and optimal production of several isotypes of Ig, but not LMP1-dependent enlargement of secondary lymphoid organs in transgenic (Tg) mice. Thus, LMP1 in vivo effects can be mediated via both TRAF binding-dependent and -independent pathways. Together with our previous findings, these results indicate that TRAF-dependent receptor functions may not always require TRAF-receptor binding. These data suggest that TRAF-mediated signaling pathways, such as those of LMP1, may be more diverse than previously appreciated. This finding has significant implications for receptor and TRAF-targeted therapies.

Introduction

EBV, the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis, latently infects >90% of humans (1). EBV preferentially maintains latency in memory B cells, and LMP1 is not expressed unless EBV partially emerges from latency, usually under conditions of immunosuppression or autoimmunity (1–3). EBV reactivation in immunocompromised patients is strongly associated with Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) (4–6), and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (7). Transient EBV reactivation is also observed in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (1, 8, 9). LMP1 is required for EBV-mediated B cell transformation and is expressed in most EBV-associated malignancies and PTLD (10–12). LMP1 has also been implicated in exacerbation of autoimmunity (13, 14).

LMP1 contains a short cytoplasmic (CY) N-terminal domain, six transmembrane (TM) domains, and a long CY C-terminal domain (15). The N-terminus anchors LMP1 to the plasma membrane and regulates LMP1 processing (16, 17). The TM domains spontaneously self-aggregate and oligomerize within the plasma membrane, leading to ligand-independent, constitutive signaling, terminated by constant and rapid LMP1 processing (16, 18). We demonstrated that the C-terminus suffices to mediate most LMP1 functions in B cells (19, 20). Engagement of hybrid receptors containing the extracellular domain of CD40 and the LMP1 C-terminus mimics LMP1 signaling, including early pathway activation and downstream B cell functions (19, 21–25).

LMP1 functionally mimics the TNFR superfamily member CD40, constitutively expressed on B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (1). Signaling through LMP1 and CD40 results in activation of various kinases and NF-κB, followed by costimulatory and adhesion molecule upregulation and cytokine production (1). However, LMP1 delivers amplified and sustained signals to B cells compared to CD40 (1). Both LMP1 and CD40 utilize TRAF adaptor proteins to induce signaling (1). The CY domains of LMP1 and CD40 each contain a shared TRAF binding site (TBS) that mediates interaction with TRAFs 1, 2, 3, and 5 (26). Interestingly, TRAF6 uses a separate binding site in the CY domain of CD40, but it associates with the shared TBS of LMP1 (27). Although LMP1 and CD40 both contain a PxQxT TRAF-binding motif, they differ in sequence around and within the variable residues of this motif (1), and these differences likely contribute to differences observed in vitro in the kinetics and amplitude of activation of signaling cascades by CD40 versus LMP1 (21).

While the functional roles of the TBS in LMP1 have been investigated using various in vitro approaches, its in vivo roles remain largely unexplored. Previous studies in B cell lines demonstrated that the LMP1 TBS is critical for surface molecule upregulation, as well as activation of JNK and NF-κB pathways (21, 28, 29). Interestingly, the TBS is not required for LMP1-mediated IL-6 or TNF-α production (21, 28). The presence of TRAF5 is required for the enlarged lymphoid organs and autoantibody production of the mCD40LMP1 Tg mouse (22), but whether direct TRAF5-LMP1 binding is critical is unknown. We predicted that the TBS is required for a distinct subset of LMP1-mediated functions in vivo.

To address this possibility, we analyzed mCD40LMP1 Tg mice in which the CY tail of LMP1 is either WT or a mutant in which the TBS no longer detectably binds TRAFs 1, 2, 3, 5, or 6 (23, 27). The Tg molecule is expressed in the absence of endogenous CD40, to aid clarity in data interpretation. We found that an intact TBS was required for LMP1 to mediate autoantibody production, the germinal center (GC) response to immunization, and efficient Ig production of various isotypes. However, the TBS was not required for LMP1-mediated enlargement of secondary lymphoid organs characteristic of the mCD40LMP1 Tg mouse. Thus, LMP1 can deliver signals in vivo that are TBS-dependent, as well as signals that are independent of the TBS.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Abs

The following Abs were used: hamster anti-mouse CD40 mAb, clone HM40.3 (unlabeled or FITC-labeled), rat anti-mouse CD16/32 mAb (blocks FcR binding), APC- or FITC-labeled anti-mouse B220 mAb (clone RA3-6B2), AlexaFluor 488-labeled rat anti-IgM and anti-mouse GL-7 Abs, and rat anti-IgG Abs (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), purified mouse IgG1 and IgM polyclonal Abs for ELISA standards, goat anti-mouse IgG1 and IgM secondary polyclonal Abs, and AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 and IgM Abs for ELISA (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Additional reagents included: ELISA alkaline phosphatase substrate tablets (5 mg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), rat serum (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR), Percoll (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), HBSS (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), and FITC-labeled peanut agglutinin (PNA) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Mice

WT C57BL/6 (WT B6) mice were obtained from NCI-Frederick (Frederick, MD) and Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The CD40−/− mice were previously described (30). The mCD40LMP1 transgenic (Tg) mice (23) and mouse (m)CD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were generated and described previously (23, 27). Briefly, to disrupt TRAF binding, we mutated proline (P204) and glutamine (Q206) residues in the TBS PxQxT motif to alanines (PQAA1) (28), and showed in both B cell lines and mice that these mutations disrupt TRAF-LMP1 interactions (24, 27). The mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were bred to CD40−/− mice so that endogenous ligand CD154 would induce signaling only through mCD40LMP1PQAA1 (23). It should be noted that since initial publication of the mCD40LMP1 Tg mouse, this strain has now been completely backcrossed to C57BL/6, resulting in a modest decrease in spleen weight from the initial report. All mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility with restricted access, and all procedures were performed as approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee, Iowa City, IA.

Flow cytometry

Spleens and cervical lymph nodes (LNs) were harvested from unimmunized 2-6-mo-old mice. 5 × 105 cells were added to wells of a 96-well plate in 200 μl HBSS + 5% FCS. Anti-mouse CD16/32 mAb (0.5 mg/ml) and rat serum (25%) were added 10 min prior to staining with FITC-and APC-labeled Abs. Flow cytometry was performed as described (27). Forward/side scatter gating for single lymphocytes was used to analyze flow cytometric data via FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Autoantibodies

Sera from 2-6-mo-old unimmunized mice were tested for anti-dsDNA and anti-cardiolipin Abs (anti-phospholipid Abs) by ELISA (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX) using the manufacturer’s protocols (23).

SRBC immunization

4-month-old mice were immunized i.p. with 0.1 ml 10% SRBC (Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO) in PBS. Ten days after immunization, spleens were harvested and flow cytometry was performed as described above.

ELISA assays

Sera from 2-6-month-old unimmunized mice were tested for production of various Ig isotypes via quantitative ELISA (23, 31, 32). Sera were diluted 1:4000 (IgG1) or 1:8000 (IgM). To measure in vitro B cell Ab production, 5 × 105 splenic B cells from WT B6, mCD40LMP1 Tg, or mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were stimulated in a 96-well plate in 200 μl RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) + 10 μM 2-ME (Invitrogen), 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), and antibiotics (Invitrogen) for 7 days with HM40.3 (anti-mCD40 mAb, 3.2 μg/ml). Supernatants were collected for ELISA, and samples were diluted 1:100 prior to assay.

B cell purification

Splenic B cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation through a 55%:65%:75% Percoll gradient. Lymphocytes at the interphase between 55% and 65% and between 65% and 75% Percoll were collected, and B cells were further purified by negative selection as described (27). Purity of isolated B cells was monitored by FACS analysis. B cell purity was >90%. Flow cytometry was performed on a Guava EasyCyte using CytoSoft software (Guava Technologies, Inc., Hayward, CA). Data were analyzed as described (27).

Statistics

Statistical comparisons were made using a two-sided unpaired Student’s t test. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Spleen and LN size

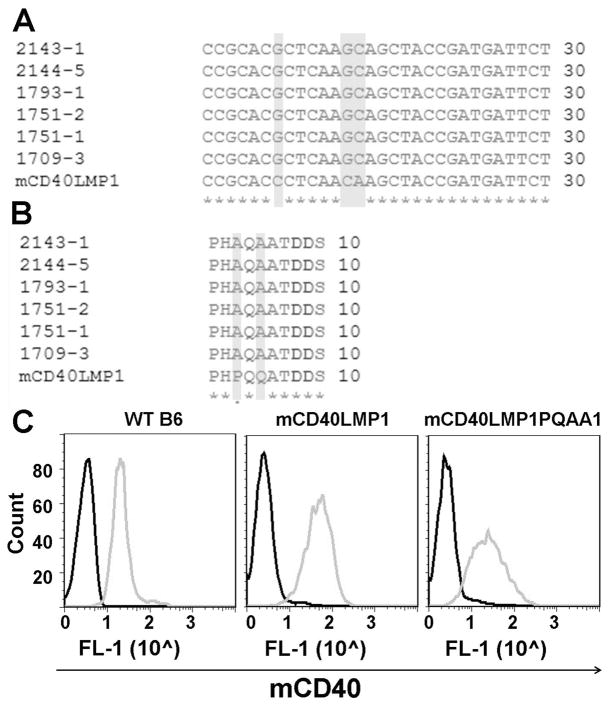

To evaluate the contributions of the TBS in LMP1 functions in vivo, we generated mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice, as described in Materials and Methods. To disrupt TRAF binding, we mutated proline (P204) and glutamine (Q206) residues in the TBS PxQxT motif to alanines (PQAA1) and performed sequence analysis of the transgene to determine that the desired mutations were present (Fig. 1A, 1B). Our goal was to directly compare in vivo outcomes of signaling by mCD40LMP1 and mCD40LMP1PQAA1, so it was important to compare both Tg receptors expressed at similar levels. Mouse B cells were stained for mCD40 surface expression, with WT B6 mice included as positive controls (Fig. 1C). Both the mCD40LMP1 and mCD40LMP1PQAA1 transgenes were expressed robustly, with levels of mCD40LMP1PQAA1 slightly lower than mCD40LMP1 expression. It is important to note that although LMP1 is a functional mimic of CD40, expressing transgenic Wt CD40 expressed at the same level and from the same transgenic promoter as mCD40LMP1 in mice does not result in the autoreactive phenotype characteristic of the mCD40LMP1 Tg mice (23).

FIGURE 1. mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg expression in mice.

(A) CLUSTAL-W-generated multiple sequence alignment depicting mutations (highlighted in gray) made in the LMP1 sequence to disrupt the TBS. Numbers on the left correspond to individual mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice, with one mCD40LMP1 Tg mouse at the bottom for comparison. (B) Similar to A, except the sequence alignment shows amino acid changes (highlighted in gray) resulting from mutations made in A. (C) Splenic B cells from a WT B6, mCD40LMP1 Tg, or mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mouse were stained with an isotype control Ab (black histograms) or anti-mCD40 Ab (gray histograms). Data shown are representative histograms (y-axis = arbitrary cell # and x-axis = log scale, where 1 is 101, etc.) from two individual experiments, where n=2–3 mice per group for each experiment.

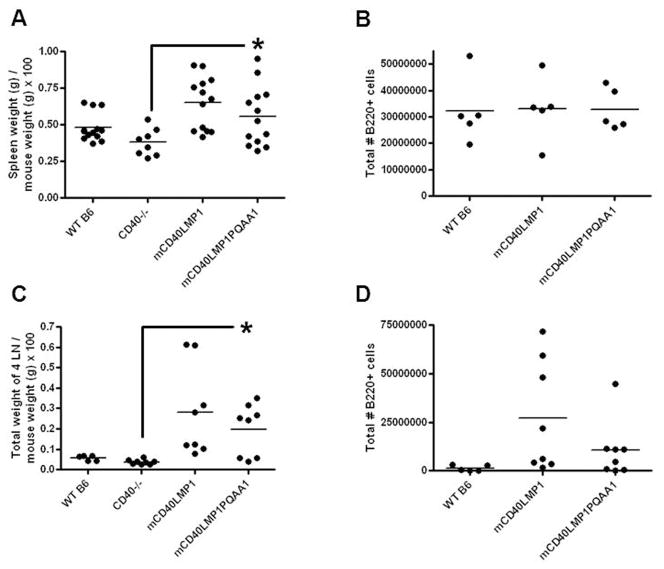

In previous work, we showed that the spleens and LNs of mCD40LMP1 Tg mice are significantly larger than those of WT B6 and CD40−/− mice. Size increase of LNs is due to B cell accumulation (23), but splenomegaly is not. The mCD40LMP1 Tg mice have modestly increased numbers of splenic macrophages (23) and dendritic cells (data not shown), which may partially contribute to enlarged spleen size, possibly via elevated IL-6 production (23). However, the exact mechanism driving splenomegaly has not been determined. Stromal elements, although challenging to quantify, may also contribute. Strikingly, disrupting the ability of the LMP1 TBS to bind TRAFs had no significant effect on LMP1-induced splenomegaly or lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2A, 2C). We normalized spleen weight and LN weight to mouse weight because we observed some differences in mouse weight and felt that this was a more accurate way to display our data. Total numbers of B cells, T cells, and macrophages in the spleens and LNs of mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were comparable to those in mCD40LMP1 Tg mice (Fig. 2B, 2D, and data not shown). Importantly, these results also indicate that the slightly lower expression of mCD40LMP1 PQAA1 compared to WT did not compromise its signaling ability. CD40−/− mice were included as controls for lymphoid organ weights in addition to WT B6 mice because our Tg mice are on a CD40−/− background. However, we chose to use WT B6 mice as controls for most experiments presented in this study, because CD40−/− mice have defective immune responses (23, 30).

FIGURE 2. Effect of TBS composition on in vivo secondary lymphoid organ characteristics.

(A) Spleen weight expressed as % of total mouse weight for WT B6, CD40−/−, mCD40LMP1 Tg, and mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice, where each point represents one mouse. (B) Total # of splenic B cells (B220+ cells), where each data point represents one mouse. (C) LN weight, where each data point represents a combined weight of 4 LNs from an individual mouse. (D) Total # of B cells in the LN. Each point represents one mouse. *p<0.05.

Autoreactivity

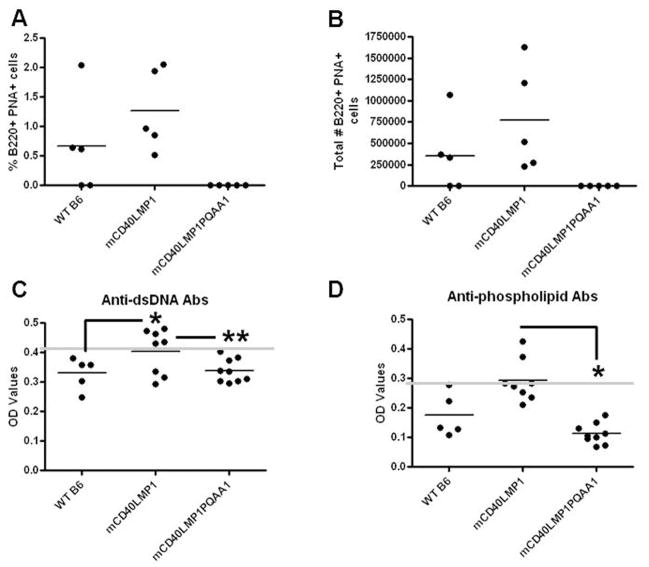

One of the most striking features of mCD40LMP1 Tg mice is the appearance of spontaneous GC B cells (B220+ PNA+) and elevated levels of serum autoantibodies in unimmunized mice (23). Spontaneous GC B cells were absent in mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice (Fig. 3A, 3B), and these mice failed to produce elevated autoantibodies against dsDNA and phospholipids compared to WT B6 mice (Fig. 3C, 3D). Thus, in contrast to LMP1-associated lymphoid organ enlargement, the TBS was required for LMP1 to induce manifestations of autoreactivity.

FIGURE 3. Role of the TBS in LMP1-mediated autoreactivity in vivo.

(A) Splenocytes from WT B6, mCD40LMP1 Tg, and mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were stained with an isotype control Ab or anti-B220 Ab and PNA as a marker for GC B cells. The % of B220+ PNA+ cells is shown. Each point represents one mouse. (B) Similar to A, except the graph depicts the total # of GC B cells. (C) Sera were tested for production of anti-dsDNA Abs by ELISA. Each data point represents one mouse. The horizontal line indicates the baseline as determined by negative controls, where samples above the line are positive. (D) Similar to C, except anti-phospholipid Ab production was measured. *p<0.05. **p<0.0001.

GC response to immunization

mCD40LMP1 can substitute for CD40 in response to immunization with TD-antigens, including induction of a germinal center response (23). To determine if the TBS played a role in LMP1-mediated GC responses, we immunized mice with SRBC. Interestingly, mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice failed to mount a GC response (Fig. 4A, 4B), as revealed by a lack of B cells expressing the GC markers PNA or GL-7. Thus, TRAF binding was required for LMP1-mediated GC responses to immunization.

FIGURE 4. Role of TRAF binding in GC responses to immunization.

(A) CD40−/− (n=1, control), mCD40LMP1 Tg (n=3), and mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg (n=3) mice were immunized i.p. with SRBC. Splenocytes were stained with an isotype control Ab or anti-B220 Ab and PNA as a marker for GC B cells. The % of B220+ PNA+ cells is shown. (B) Similar to A, except splenocytes were stained with anti-B220 Ab and GL-7 Ab as a marker for GC B cells. n.d. = not detected, *p<0.05.

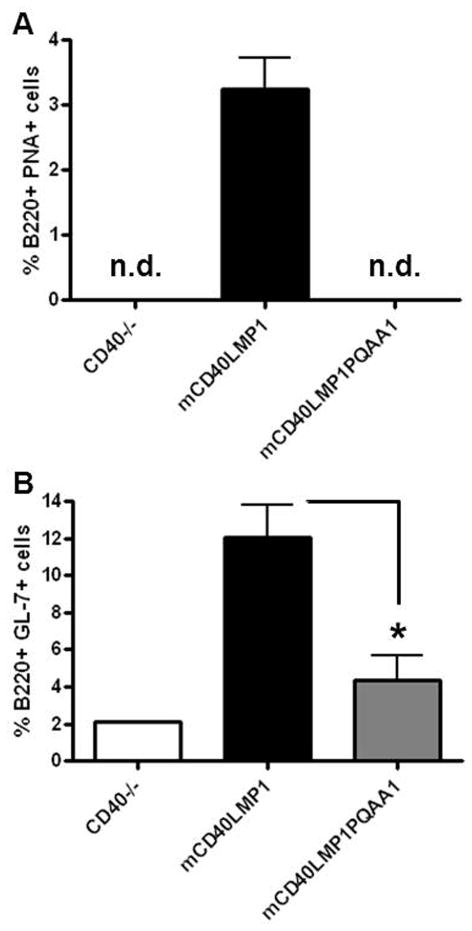

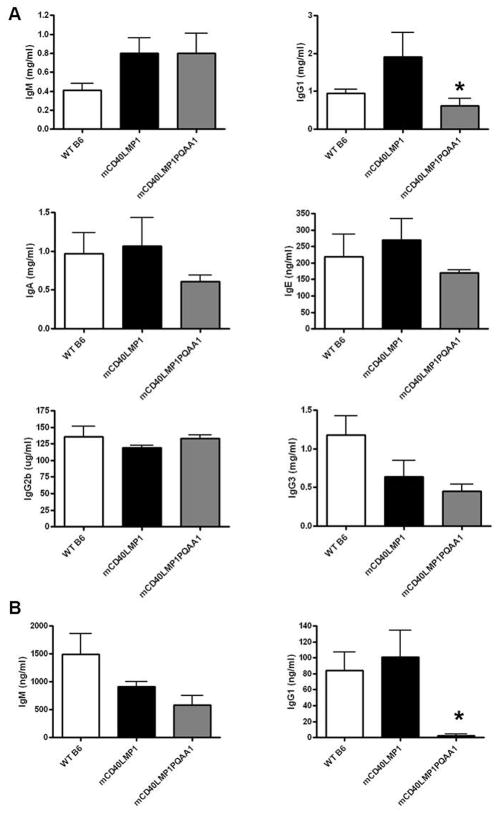

Ig production

We previously demonstrated that mCD40LMP1 substitutes for CD40 to mediate normal T-dependent Ab responses (23), and mCD40LMP1 Tg mice have normal serum levels of all Ig isotypes, restoring the defect in isotype switching characteristic of mice with absent CD40 signaling (1, 23, 30). Serum levels of IgM in mCD40LMP1 versus mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were similar, but mice expressing the TBS mutant had a marked reduction in serum IgG1 (Fig. 4A). There were no consistent differences in serum IgG2b or IgG3, but there was a downward trend in serum IgA and IgE in mCD40LMP1PQAA1 compared to mCD40LMP1 Tg mice (Fig. 4A). B cells from mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice also failed to produce IgG1 following in vitro stimulation through mCD40LMP1 (Fig. 4B). Thus, the TBS of LMP1 was required for LMP1 to mediate production of Ig of certain isotypes, particularly the IgG1 isotype that dominates many T-dependent humoral responses.

Discussion

TRAFs play critical roles in LMP1 signaling (22, 25, 27, 33–35), but whether their in vivo roles are dependent or independent of LMP1 binding was not known. Results presented here indicate that the TBS of LMP1 was required for in vivo production of spontaneous GC B cells, autoantibody production, and GC responses to immunization. TRAF binding also played a key role in LMP1-mediated IgG1 production, and enhanced production of IgA and IgE. However, the TBS was not required for LMP1-mediated splenomegaly or lymphadenopathy in Tg mice. These findings indicate that the LMP1 CY domain required TRAF binding to effectively substitute for CD40 and induce signaling pathways required for certain downstream B cell functions. However, LMP1-mediated signals that lead to enlarged secondary lymphoid organs did not require direct TRAF association with LMP1.

A number of different factors may contribute to the TBS-independent LMP1-mediated secondary lymphoid organ enlargement. There are several cell types in the spleen that may contribute to splenomegaly, as the mCD40LMP1 transgene is driven by an MHC class II promoter. Original selection of this transgenic promoter was designed to allow us to test the ability of the LMP1 CY domain to substitute for CD40 on all immune cells that normally express CD40, so mCD40LMP1 is also expressed on myeloid cells (23). The mCD40LMP1 Tg mice have modestly increased numbers of splenic macrophages (23) and dendritic cells (data not shown), which may contribute to splenomegaly. There are also non-immune cells in the spleen which could play a role in spleen enlargement, such as stromal cells. However, this cell population is very challenging to quantify. Additionally, TRAF molecules are utilized by a variety of receptors expressed on many different of cell types (36). Many, though not all, of these receptors directly bind TRAFs. These receptors deliver activation and/or survival signals and thus, any number of these pathways could contribute to lymphoid tissue enlargement. Lastly, we previously showed that TRAF binding is not required for LMP1-mediated IL-6 production (37). The mCD40LMP1 Tg mice have significantly elevated serum levels of IL-6 (23), which could also contribute to enlarged lymphoid organs.

TBS-independent in vivo functions of LMP1 could be induced in a completely TRAF-independent manner, but could also result from pathways that require the TRAFs in a non-receptor-associated role. TRAFs participate in this manner in innate immune receptor signaling (38), and TRAF6 binding to CD40 is dispensable for TRAF6-dependent JNK activation and CD80 upregulation by CD40 in B cells (39). In this regard, mCD40LMP1 Tg mice deficient in TRAF5 have spleens and LNs comparable in size to WT B6 mice (22), indicating that LMP1-mediated lymphoid organ enlargement is TRAF5-dependent. It has been widely assumed that if a receptor binds TRAFs and also requires them for function, TRAF binding must be required for receptor function. The present results reveal an important caveat to such assumptions, and indicate that signaling pathways mediated by LMP1 – and quite likely additional TRAF-utilizing and binding receptors – are more varied and complex than have been appreciated. This idea has broad implications not only for our understanding of these pathways, but for therapeutic design as well. TRAF molecules are utilized by numerous receptors expressed on a wide variety of cell types, including CD40 (40) and other TNFR superfamily members (41), TLRs (42–45), IL-1βR (46), IL-17R (46–48), IL-25R (49), and TCR (50). As TRAF function is both receptor- and cell type-specific (42), the requirement of TRAF binding should be carefully evaluated in each situation. Taken together, our data suggest that TRAF-associated therapies may be most effective if the TRAF molecule itself, and not simply TRAF-receptor binding, was targeted.

FIGURE 5. Requirement of the TBS for Ig production.

(A) Sera from WT B6 (n=5), mCD40LMP1 Tg (n=6), and mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg (n=7) mice were tested for serum IgM, IgG1, IgA, IgE, IgG2b, or IgG3 production via ELISA. (B) Splenic B cells (n=3 mice per group) from WT B6, mCD40LMP1 Tg, and mCD40LMP1PQAA1 Tg mice were stimulated with anti-mCD40 Ab for 7 days. Supernatants were collected for IgM (left panel) and IgG1 (right panel) ELISAs. Data in all panels are mean values ± SEM. *p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Laura Stunz for valuable discussion, and Dr. Bruce Hostager for critical feedback on this manuscript.

This study was supported by the American Heart Association Midwest Affiliate Predoctoral Fellowship (KMA) and NIH R01 CA099997 (GAB). This work was supported in part with resources and the use of facilities at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Abbreviations in this article

- B6

C57BL/6

- CY

cytoplasmic

- GC

germinal center

- LMP1

latent membrane protein 1

- LN

lymph node

- mCD40

mouse CD40

- PTLD

post-transplant lymphomas/lymphoproliferative disease

- TRAF

Tg, transgenic

- TM

transmembrane

- TNFR

associated factor

- TBS

TRAF binding site

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Graham JP, Arcipowski KM, Bishop GA. Differential B lymphocyte regulation by CD40 and its viral mimic, LMP1. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:226–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Küppers R. B cells under influence: transformation of B cells by EBV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:801–812. doi: 10.1038/nri1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV: exploiting the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:75–82. doi: 10.1038/35095584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schubert S, Abdul-Khaliq H, Lehmkuhl HB, Yegitbasi M, Reinke P, Kebelmann-Betzig C, Hauptmann K, Gross-Wieltsch U, Hetzer R, Berger F. Diagnosis and treatment of PTLD in pediatric heart transplant patients. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons SF, Liebowitz DN. The roles of human viruses in the pathogenesis of lymphoma. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:461–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrell PJ, Cludts I, Stuhler A. Epstein-Barr virus genes and cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 1997;51:258–267. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(97)83541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam P, Bonzheim I, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of the elderly. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:349–355. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318229bf08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S. Inflammation: a pivotal link between autoimmune diseases and atherosclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross AJ, Hochberg D, Rand WM, Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV and systemic lupus erythematosus: a new perspective. J Immunol. 2005;174:6599–6607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middeldorp JM, Pegtel DM. Multiple roles of LMP1 in EBV induced immune escape. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheinfeld AG, Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Knowles DM. EBV LMP1 Oncogene Deletion in PTLD. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:805–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaye KM, Izumi KM, Kieff E. EBV LMP1 is essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation: EBV strategy in normal and neoplastic B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9150–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters AL, Stunz LL, Meyerholz DK, Mohan C, Bishop GA. LMP1, the EBV-encoded oncogenic mimic of CD40, accelerates autoimmunity in B6. Sle1 mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:4053–4062. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole BD, Templeton AK, Guthridge JM, Brown EJ, Harley JB, James JA. Aberrant Epstein-Barr viral infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liebowitz D, Wang D, Kieff E. Orientation and patching of the latent infection membrane protein encoded by EBV. J Virol. 1986;58:233–237. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.233-237.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aviel S, Winberg G, Massucci M, Ciechanover A. Degradation of the EBV LMP1 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Targeting via ubiquitination of the N-terminal residue. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23491–23499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izumi KM, Kaye KM, Kieff ED. EBV recombinant molecular genetic analysis of the LMP1 amino-terminal cytoplasmic domain reveals a probable structural role, with no component essential for primary B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1994;68:4369–4376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4369-4376.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gires O, Zimber-Strobl U, Gonnella R, Ueffing M, Marschall G, Zeidler R, Pich D, Hammerschmidt W. LMP1 of EBV mimics a constitutively active receptor molecule. EMBO J. 1997;16:6131–6140. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown KD, Hostager BS, Bishop GA. Differential signaling and TRAF degradation by CD40 and the EBV oncoprotein LMP1. J Exp Med. 2001;193:943–954. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busch LK, Bishop GA. The EBV transforming protein, LMP1, mimics and cooperates with CD40 signaling in B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:2555–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham J, Moore C, Bishop G. Roles of the TRAF2/3 binding site in differential B cell signaling by CD40 and its viral oncogenic mimic, LMP1. J Immunol. 2009;183:2966–2973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraus ZJ, Nakano H, Bishop GA. TRAF5 is a critical mediator of in vitro signals and in vivo functions of LMP1, the viral oncogenic mimic of CD40. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17140–17145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903786106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stunz LL, Busch LK, Munroe ME, Tygrett L, Sigmund C, Waldschmidt TW, Bishop GA. Expression of the LMP1 cytoplasmic tail in mice induces hyperactivation of B lymphocytes and disordered lymphoid architecture. Immunity. 2004;21:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie P, Bishop GA. Roles of TRAF3 in signaling to B lymphocytes by CTAR regions 1 and 2 of the EBV-encoded oncoprotein LMP1. J Immunol. 2004;173:5546–5555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie P, Hostager BS, Bishop GA. Requirement for TRAF3 in signaling by LMP1, but not CD40, in B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:661–671. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devergne O, Hatzivassiliou E, Izumi KM, Kaye KM, Kleijnen MF, Kieff E, Mosialos G. Association of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 with an EBV LMP1 domain important for B-lymphocyte transformation: role in NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7098–7108. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arcipowski KM, Stunz LL, Graham JP, Kraus ZJ, Vanden Bush TJ, Bishop GA. Molecular mechanisms of TRAF6 utilization by the oncogenic viral mimic of CD40, LMP1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9948–9955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busch LK, Bishop GA. Multiple carboxyl-terminal regions of the EBV oncoprotein, LMP1, cooperatively regulate signaling to B lymphocytes via TRAF-dependent and TRAF-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2001;167:5805–5813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luftig M, Yasui T, Soni V, Kang MS, Jacobson N, Cahir-McFarland E, Seed B, Kieff E. EBV LMP1 TRAF-binding site induces NIK/IKK alpha-dependent noncanonical NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:141–146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237183100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, Tanaka T, Fujiwara H, Suematsu S, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H. The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1994;1:167–178. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie P, Stunz LL, Larison KD, Yang B, Bishop GA. TRAF3 is a critical regulator of B cell homeostasis in secondary lymphoid organs. Immunity. 2007;27:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldschmidt TJ, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McElmurry RT, Tygrett LT, Taylor PA, Blazar BR. Abnormal T cell-dependent B-cell responses in SCID mice receiving allogeneic bone marrow in utero. Severe combined immune deficiency. Blood. 2002;100:4557–4564. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eliopoulos AG, Waites ER, Blake SM, Davies C, Murray P, Young LS. TRAF1 is a critical regulator of JNK signaling by the TRAF-binding domain of the EBV-encoded LMP1 but not CD40. J Virol. 2003;77:1316–1328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1316-1328.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schultheiss U, Püschner S, Kremmer E, Mak TW, Engelmann H, Hammerschmidt W, Kieser A. TRAF6 is a critical mediator of signal transduction by the viral oncogene LMP1. EMBO J. 2001;20:5678–5691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaye KM, Devergne O, Harada JN, Izumi KM, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E, Mosialos G. TRAF2 is a mediator of NF-kappa B activation by LMP1, the EBV transforming protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11085–11090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie P, Kraus ZJ, Stunz LL, Bishop GA. Roles of TRAF molecules in B lymphocyte function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Busch LK. Ph D Dissertation. The University of Iowa; 2001. Molecular mechanisms of LMP1 signaling to B lymphocytes. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown J, Wang H, Hajishengallis GN, Martin M. TLR-signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. J Dent Res. 2011;90:417–427. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowland SR, Tremblay ML, Ellison JM, Stunz LL, Bishop GA, Hostager BS. A novel mechanism for TRAF6-dependent CD40 signaling. J Immunol. 2007;179:4645–4653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elgueta R, Benson MJ, de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Guo Y, Noelle RJ. Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:152–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dempsey PW, Doyle SE, He JQ, Cheng G. The signaling adaptors and pathways activated by TNF superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:193–209. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie P, Poovassery J, Stunz LL, Smith SM, Schultz ML, Carlin LE, Bishop GA. Enhanced Toll-like receptor (TLR) responses of TRAF3-deficient B lymphocytes. J Leukocyte Biol. 2011;90:1149–1157. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0111044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oganesyan G, Saha SK, Guo B, He JQ, Shahangian A, Zarnegar B, Perry A, Cheng G. Critical role of TRAF3 in the Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent antiviral response. Nature. 2006;439:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature04374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeshita F, Ishii KJ, Kobiyama K, Kojima Y, Coban C, Sasaki S, Ishii N, Klinman DM, Okuda K, Akira S, Suzuki K. TRAF4 acts as a silencer in TLR-mediated signaling through the association with TRAF6 and TRIF. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2477–2485. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwandner R, Yamaguchi K, Cao Z. Requirement of TRAF6 in interleukin 17 signal transduction. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1233–1240. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zepp JA, Liu C, Qian W, Wu L, Gulen MF, Kang Z, Li X. Cutting Edge: TRAF4 Restricts IL-17-Mediated Pathology and Signaling Processes. J Immunol. 2012;189:33–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu S, Pan W, Shi P, Gao H, Zhao F, Song X, Liu Y, Zhao L, Li X, Shi Y, Qian Y. Modulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through TRAF3-mediated suppression of interleukin 17 receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2647–2662. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maezawa Y, Nakajima H, Suzuki K, Tamachi T, Ikeda K, Inoue J, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Involvement of TRAF6 in IL-25 receptor signaling. J Immunol. 2006;176:1013–1018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie P, Kraus ZJ, Stunz LL, Liu Y, Bishop GA. TRAF3 is required for T cell-mediated immunity and TCR/CD28 signaling. J Immunol. 2011;186:143–155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]