TO THE EDITOR:

The use of omega-3 fatty acids for depression treatment is of considerable interest, in part due to the inadequate efficacy and tolerability of standard antidepressant medications. Although several meta-analyses have reported positive outcomes for omega-3 fatty acid treatment of depression,1-5 an up-to-date meta-analysis by Bloch and Hannestad that includes the latest trials and uses sophisticated meta-regression techniques to account for study heterogeneity, suggests no significant benefit.6

However, caution must be undertaken when interpreting these findings. Omega-3 fatty acids have been found to have antidepressant effects in patients with DSM-defined major depressive disorder (MDD) but not “mood-improving” effects on symptomatic individuals in which the diagnosis was not confirmed.3,7 This meta-analysis, however, includes studies and subjects which were not rigorously diagnosed with strict DSM MDD. It is therefore not accurate to describe this paper as a meta-analysis for MDD (e.g. from the first line of the Abstract to the last paragraph of the Discussion).”6

The major concern is the inclusion of Rogers and colleagues’ clinical trial,8 which represented a 31.7% weight of the pooled estimate among a total of 13 selected clinical trials. In Rogers et al, individuals were enrolled for omega-3 fatty acid supplementation according to a self-rating of the short form of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS) in settings such as general practice surgeries, shopping malls, and university freshman fairs,8 indicating that individuals were not rigorously evaluated for MDD by health professionals. Therefore, Rogers’ study should have been excluded in the meta-analysis since it lacks the more rigorous assessment measures (primarily the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) used in the other selected studies.

The study by Lucas and colleagues9 should also be excluded because they recruited women with moderate to severe psychological distress (rather than MDD), defined by a self-rating of Psychological General Wellbeing Schedule from the general population through newspaper, radio and television advertising, and flyers posted.

Finally, the stratification of baseline depression severity requires clarification prior to meta-regression. As noted earlier, baseline depression severity was determined primarily by the Hamilton-D or the Montgomery Asberg ratings scales; however, two studies used only self-rating scales of DASS8 and Psychological General Wellbeing Schedule.9 It should be explained how the self-rating scales were standardized against the Hamilton or the Montgomery Asberg ratings scales.

After withdrawing the 2 clinical trials8,9 due to above-mentioned faults, the other 11 trials fulfilled Bloch and Hannestad's6 original criteria. We performed a modified analysis on the main results by using RevMan program (Review Manager, version 5.1, Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2011). With 254 patients with omega-3 treatment and 222 patients with placebo treatment included, a significant antidepressant effect of omega-3 fatty acids could be found (SMD = 0.29, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.10, 0.48, P = 0.003) (Figure). There was significant heterogeneity among studies (Chi2 = 35.4, df = 10 (P = 0.0001), I2 = 72%). The pooled effect remained significant even when using a random effects model (SMD = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.88, P = 0.008).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of treatment effects of omega-3 fatty acids for major depression.

In summary, Bloch and Hannestad might have over-concluded that “nearly all of the treatment efficacy observed in the published literature may be attributable to publication bias.” Omega-3 fatty acids may have antidepressant effects in patients with MDD but not “mood-improving” effects in individuals with only non-clinical depressive symptoms. In addition, omega-3 fatty acids should be separately and rigorously assessed both as monotherapy and as augmentation of antidepressants. Meta-analyses, just like randomized clinical trials, may be affected by potential biases in terms of selection of trials (or patients) for analysis. Both need to be equally designed to be specific regarding their subjects’ diagnostic status.

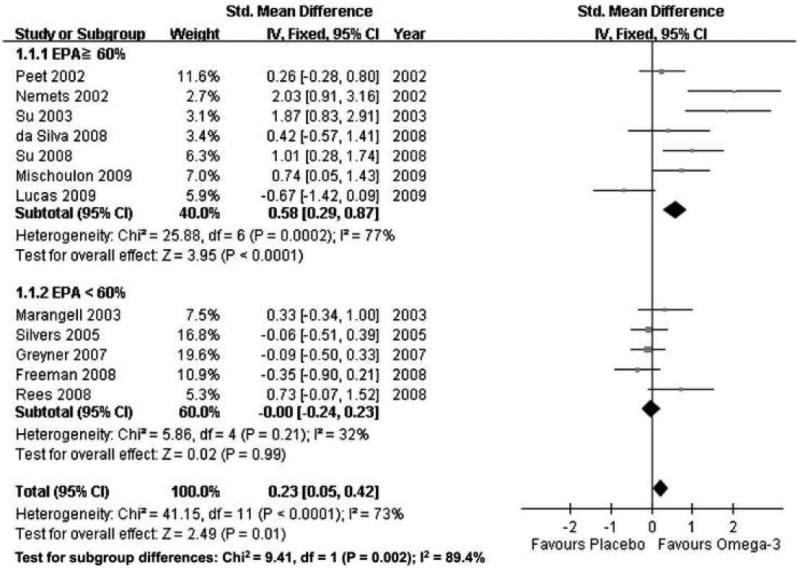

Figure 2.

Forest plot of treatment effects of omega-3 fatty acids for major depression, separated by percentage of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in omega-3 preparation: EPA ≥ 60% and EPA < 60%.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: PY Lin and KP Su wrote the first draft of the letter. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the letter. Dr. David Mischoulon has received research support for other clinical trials from Amarin (Laxdale), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cederroth, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Nordic Naturals, Ganeden, Swiss Medica, and Fisher-Wallace; he has received consulting and writing honoraria from Pamlab; he has received speaking honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Nordic Naturals, Pfizer, Pamlab, and Virbac; he has received royalty income from Back Bay Scientific for PMS Escape, and from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for the book, “Natural Medications for Psychiatric Disorders: Considering the Alternatives” (Editors: David Mischoulon and Jerrold F Rosenbaum). Dr. Marlene P. Freeman has received research support for clinical trials from Lilly, Forrest and Glaxo SmithKline; she has received consulting honoraria for the Advisory Board from Bristol Myers Squibb. The remaining authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, Davis JM, Mischoulon D, Peet M, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1954–1967. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman MP, Mischoulon D, Tedeschini E, Goodness T, Cohen LS, Fava M, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):682–688. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r05976blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Ness AR. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:757–770. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, Mann JJ. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06634. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin PY, Su KP. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1056–1061. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch MH, Hannestad J. Mol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.100. e-pub ahead of print 20 Sep 2011; doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin PY, Huang SY, Su KP. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers PJ, Appleton KM, Kessler D, Peters TJ, Gunnell D, Hayward RC, et al. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:421–431. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507801097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucas M, Asselin G, Merette C, Poulin M, Dodin S. Menopause. 2009;16:357–366. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181865386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]