Abstract

Aims and objectives

Test the feasibility and validity of a handoff evaluation tool for nurses.

Background

No validated tools exist to assess the quality of handoff communication during change of shift.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Methods

A standardised tool, the Handoff CEX, was developed based on the mini-CEX. The tool consisted of seven domains scored on a 1–9 scale. Nurse educators observed shift-to-shift handoff reports among nurses and evaluated both the provider and recipient of the report. Nurses participating in the report simultaneously evaluated each other as part of their handoff.

Results

Ninety-eight evaluations were obtained from 25 reports. Scores ranged from 3–9 in all domains except communication and setting (4–9). Experienced (>five years) nurses received significantly higher mean scores than inexperienced (≤five years) nurses in all domains except setting and professionalism. Mean overall score for experienced nurses was 7·9 vs 6·9 for inexperienced nurses. External observers gave significantly lower scores than peer evaluators in all domains except setting. Mean overall score by external observers was 7·1 vs. 8·1 by peer evaluators. Participants were very satisfied with the evaluation (mean score 8·1).

Conclusions

A brief, structured handoff evaluation tool was designed that was well-received by participants, was felt to be easy to use without training, provided data about a wide range of communication competencies and discriminated well between experienced and inexperienced clinicians.

Relevance to clinical practice

This tool may be useful for educators, supervisors and practicing nurses to provide training, ongoing assessment and feedback to improve the quality of handoff.

Keywords: communication, evaluation, handover, nurses, nursing, nursing education, transfer of care

Introduction

Nursing handoffs at shift changes vary widely in form, content and quality. They range in complexity from taped or written reports left by off-going nurses for incoming nurses (Cox 1994, Baldwin & Mcginnis 1994, Barbera et al. 1998) to bedside report where incoming nurses, off-going nurses and patients mutually discuss the plan of care (Taylor 1993, Anderson & Mangino 2006). Some are standardised using one of a variety of templates (Schroeder 2006, Haig et al. 2006, No authors listed 2007, Wilson 2007, Block et al. 2010), most are not. Studies of nursing handoffs have identified a variety of problems, including incomplete or inaccurate information, uneven quality, limited opportunities for questions, incorrect judgments and repeated interruptions (Clair & Trussell 1969, Riesenberg et al. 2010, Welsh et al. 2010, Calleja et al. 2011). In turn, these may contribute to error through omissions, misunderstandings and delays (Anthony & Preuss 2002, Ebright et al. 2004, Sexton et al. 2004, Pothier et al. 2005, Sharit et al. 2008). Similar problems have been noted with handoffs between physicians and other providers (Beach et al. 2003, Arora et al. 2005, 2007, Gandhi 2005, Jagsi et al. 2005, Greenberg et al. 2007, Borowitz et al. 2008, Horwitz et al. 2008, Kitch et al. 2008).

On the other hand, a well-conducted handoff serves as an opportunity for critical reassessment and error reduction (Lee et al. 1996, Miller 1998, Lally 1999, Parker & Coiera 2000, Kerr 2002, Patterson et al. 2004, Paine & Millman 2009, Salerno et al. 2009). Systematic overhauls of nurse handovers have been described to reduce adverse events (Alvarado et al. 2006). Furthermore, nursing handoffs serve important roles in acculturation, socialisation and education (Parker et al. 1992, Ekman & Segesten 1995, Lally 1999, Hays 2002).

For both these reasons, the World Health Organization (WHO Collaborating centre for patient safety solutions 2007) and organisations in many nations, including the USA (The Joint Commission 2009, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2010), UK (British Medical Association, National Patient Safety Agency & NHS Modernisation Agency 2004) and Australia (Australian Medical Association 2006, Australian Commission On Safety and Quality In Health Care 2010), have focused increasing attention on the handoff as a key component of patient safety. In the USA, standardised handovers are an accreditation requirement for hospitals (The Joint Commission 2009), and competency in handoff skills is a requirement for physicians in training (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2010). Likewise, there have been widespread calls for standardisation of nursing handovers (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare 2005, Hohenhaus et al. 2006, Riesenberg et al. 2010). Standards for evaluation of nursing handoffs, however, have not been established.

To date, there are no established tools for assessing the quality of the verbal handoff, also referred to as ‘sign-out’ or ‘report (Riesenberg et al. 2009), nor are there tools to assess the competency of the handoff participants (Riesenberg et al. 2009). The lack of validated assessment tools makes it challenging for hospitals to ensure that their clinical providers, including nurses and physicians, are competent in this important skill. It also makes it difficult to assess the impact and sustainability of interventions to improve the handoff process.

To address this need, we developed a structured handoff assessment tool, the Handoff CEX (Farnan et al. 2010), based on a previously validated educational assessment, the mini-CEX (Norcini et al. 1995, 2003). The mini-CEX uses a 9-point scale in several domains and is widely used to evaluate students and trainees. This study was designed to test the feasibility and discriminatory power of the Handoff CEX in real-world practice settings among hospital nurses.

Methods

Tool design

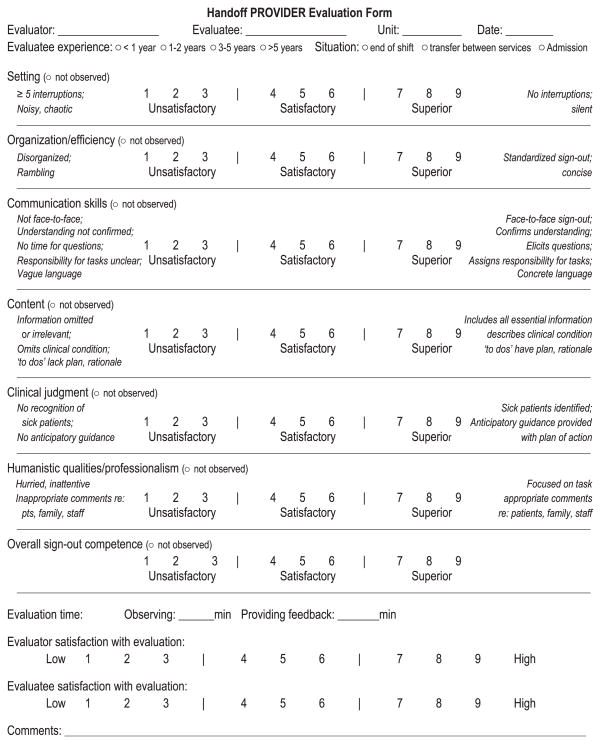

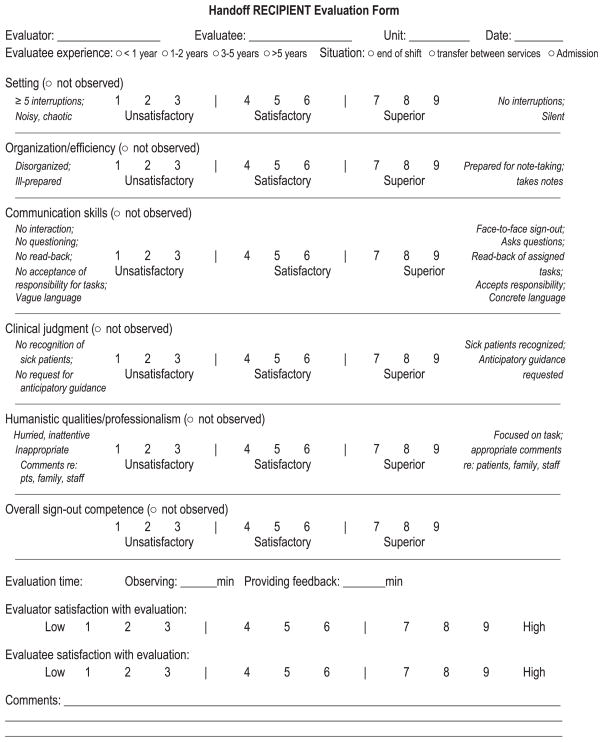

Based on expert opinion, clinical guidelines and published literature, we identified six main domains for handoff assessment: setting, organisation, communication, content, judgment and professionalism. In addition, we added an assessment of overall competency. We based the format and structure of the tool on a previously validated, widely used, real-time educational evaluation tool (the Mini-CEX) (Norcini et al. 1995). Each domain was scored on a 1–9 point scale and included descriptive anchors at high and low ends of performance to orient the evaluator. The scale was divided into unsatisfactory (score 1–3), satisfactory (4–6) and superior (7–9) sections to further guide the evaluator. We designed two tools, one to assess the person providing the handoff and one to assess the handoff recipient, each with unique role-based anchors (Figs 1 and 2). The recipient evaluation tool did not include a domain for content.

Figure 1.

Handoff provider assessment tool.

Figure 2.

Handoff recipient assessment tool.

Feasibility assessment

We selected a convenience sampling of routine shift-to-shift nurse reports both in the morning and the evening on three units (one medicine, one surgical and one cardiovascular) to ensure a range of patient types and nurse experience. Each nurse report was observed by an experienced nurse evaluator (either a nurse educator or clinical nurse manager) who had received only a brief (<five minutes) overview of the tool by the study coordinator. For the nurse providing report, an evaluation tool was completed by both the nurse evaluator and the nurse receiving report. For the nurse receiving report, an evaluation tool was completed by the nurse evaluator and by the nurse providing report. Consequently, each report included in the study generated four evaluations: two of the nurse providing report and two of the nurse receiving report. No training in use of the tool was provided to peer evaluators. Feedback of the results of the evaluation was given to each nurse in real time by the evaluators; to do this, evaluators were instructed to review the scores on each domain with the nurse with explanations for low scores. The tool also included space for open-ended comments about the report or the tool.

Each nurse provided verbal informed consent. The study was approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee (HIC) and by the Yale New Haven Hospital Research Committee. The HIC granted a HIPAA waiver to cover patient information discussed during report and a waiver of informed patient consent. No patient information was recorded during the study.

Statistical analysis

We obtained the median and range of scores for each domain. We stratified nurses by years of experience (≤five years and >five years) and used the Student’s t-test to compare the effect of participant experience on assessment scores. We confirmed the results using the nonparametric Wilcoxon test; as the results were the same, we report the t-test results. We used Spearman’s correlation coefficients to describe correlation between domains. We used paired t-tests to compare external evaluator ratings with peer ratings of the same handoff. Finally, we tested the inter-rater reliability of the tool by calculating a weighted kappa. We described open-ended comments in a narrative fashion as there were too few comments to conduct a formal qualitative analysis. Statistical significance was defined by a p value ≤ 0·05, and analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 25 shift-to-shift nurse reports were observed between October, 2007 and June, 2008, yielding a total of 98 evaluations. Participants reported spending a mean of 7·3 (SD 4·5) minutes observing report and 2·0 (SD 1·2) minutes providing feedback. The evaluators rated their satisfaction with the tool highly, at a mean of 8·2 (0·9). Overall, nurses received high marks for reports, but there was a wide range of scores for both the provider (giving the handoff) and recipient (receiving the handoff).

Handoff providers

A total of 49 evaluations of handoff providers were completed for 25 nurses. For each domain except communication and setting, scores spanned the full range from unsatisfactory to superior (Table 1). The highest rated variable on the handoff provider evaluation tool was professionalism, with a mean of 7·7 (SD 1·4). The lowest rating was for setting, with a mean of 7·1 (SD 1·4). Handoff providers gave high ratings for their satisfaction with the evaluation, at a mean of 8·1 (SD 1·4).

Table 1.

Mean and range of scores in each domain

| Domain | Provider of handoff (n = 49)

|

Recipient of handoff (n = 49)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Weighted kappa (Adjusted SE) | Mean (SD) | Range | Weighted kappa (Adjusted SE) | |

| Setting | 7·1 (1·4) | 4–9 | 0·30 (0·15) | 7·1 (1·4) | 4–9 | 0·36 (0·16) |

| Organisation | 7·4 (1·6) | 3–9 | 0·48 (0·14) | 7·6 (1·2) | 5–9 | 0·30 (0·15) |

| Communication | 7·4 (1·5) | 4–9 | 0·29 (0·13) | 7·6 (1·3) | 4–9 | 0·44 (0·14) |

| Content | 7·2 (1·6) | 3–9 | 0·46 (0·16) | N/A | N/A | |

| Judgment | 7·4 (1·6) | 3–9 | 0·46 (0·13) | 7·5 (1·1) | 4–9 | 0·35 (0·16) |

| Professionalism | 7·7 (1·4) | 3–9 | 0·39 (0·18) | 7·5 (1·6) | 1–9 | 0·48 (0·13) |

| Overall | 7·4 (1·5) | 3–9 | 0·43 (0·13) | 7·6 (1·1) | 4–9 | 0·41 (0·16) |

| Satisfaction with evaluation | 8·1 (1·4) | 4–9 | 8·2 (1·2) | 4–9 | ||

SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; N/A, not applicable – content is not a domain on the recipient evaluation tool.

Handoff recipients

A total of 49 evaluations of handoff recipients were completed for 25 nurses. The range of scores was narrower than for the provider assessments, spanning the satisfactory to superior ranges (Table 1). For the handoff recipient evaluation tool, both organisation and communication scored the highest with a mean of 7·7 (SD 1·2 and SD 1·3, respectively). The lowest score was also for setting, at 7·1 (SD 1·4). The overall quality of recipients’ report performance was assessed at a mean of 7·6 (SD 1·1) compared with 7·4 (SD 1·5) for providers’ performance. Handoff recipients gave high ratings for their satisfaction with the evaluation, at a mean of 8·2 (SD 1·2).

Subgroup analyses

Evaluations were evenly divided among nurses with >five years of experience (n = 23) and those with ≤five years of experience (n = 22). Experienced (>five years) nurses received significantly higher scores than inexperienced (≤five years) nurses in all domains except setting and professionalism (Table 2). For example, experienced nurses received a mean of 7·9 for overall competency, compared with 6·9 for inexperienced nurses (mean difference 1·0 points, 95% CI 0·2–1·9, p = 0·03).

Table 2.

Mean and range of scores for providers of handoff, stratified by years of experience

| Domain | ≤five years experience (n = 22)

|

>five years experience (n = 23)

|

p-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | ||

| Setting | 6·7 (1·4) | 4–9 | 7·4 (1·5) | 4–9 | 0·11 |

| Organisation | 6·7 (1·8) | 3–9 | 8·3 (0·8) | 6–9 | <0·001 |

| Communication | 6·7 (1·8) | 4–9 | 8·2 (1) | 6–9 | 0·001 |

| Content | 6·4 (1·9) | 3–9 | 7·9 (1) | 6–9 | 0·003 |

| Judgment | 6·7 (1·9) | 3–9 | 8·1 (1) | 6–9 | 0·005 |

| Professionalism | 7·8 (1·4) | 3–9 | 7·8 (1·5) | 3–9 | 0·98 |

| Overall | 6·9 (1·8) | 3–9 | 7·9 (1·2) | 6–9 | 0·03 |

| Satisfaction with evaluation | 7·2 (1·8) | 4–9 | 8·8 (0·4) | 8–9 | 0·007 |

SD, Standard deviation.

p-values based on t-statistics for independent samples.

External evaluators consistently gave lower marks for the same report than the peer evaluators did, with the exception of the setting domain, which was similar in both (Table 3). For example, external evaluators gave subjects an average score of 7·1 for overall quality, whereas peer evaluators gave subjects an average score of 8·1 (mean difference 1·1 points, 95% CI 0·5–1·6 points, p < 0·001).

Table 3.

Mean and range of scores for providers and recipients of handoff, stratified by external versus peer evaluator

| Domain | External observers (n = 34)

|

Peer evaluators (n = 34)

|

Mean difference peer – external score (95% CI) | p-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |||

| Setting | 7·3 (1·4) | 4–9 | 7·4 (1·4) | 4–9 | 0·0 (30·6 to 0·6) | 0·92 |

| Organisation | 6·9 (1·5) | 3–9 | 7·9 (1·2) | 5–9 | 1·0 (0·5 to 1·5) | <0·001 |

| Communication | 7·0 (1·5) | 4–9 | 7·9 (1·3) | 5–9 | 0·9 (0·4 to 1·4) | <0·001 |

| Content | 6·5 (2·0) | 3–9 | 7·9 (1·2) | 5–9 | 1·5 (0·2 to 2·8) | 0·03 |

| Judgment | 6·9 (1·7) | 3–9 | 8·0 (1·1) | 5–9 | 1·1 (0·5 to 1·6) | <0·001 |

| Professionalism | 7·4 (1·2) | 3–9 | 8·1 (1·3) | 3–9 | 0·7 (0·3 to 1·2) | 0·004 |

| Overall | 7·1 (1·6) | 3–9 | 8·1 (0·9) | 6–9 | 1·1 (0·5 to 1·6) | <0·001 |

SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

p-values based on t-statistics for paired samples.

Inter-rater reliability and domain correlation

Excluding setting, Spearman’s correlation coefficients among the CEX domains ranged from 0·53–0·95 (p < 0·001 for most correlations). Setting was more weakly correlated with the other domains, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0·24–0·40. Correlations between individual domains and the overall competence rating ranged from 0·78–0·92 for all domains excluding setting (p < 0·001) and was 0·40 for setting (p = 0·004).

Weighted kappa scores for provider evaluations ranged from 0·29–0·48, generally considered in the fair–moderate range (Table 1) (Altman 1991). Weighted kappa scores for recipient evaluations similarly ranged from 0·30–0·48.

Open-ended comments

Twenty of the evaluations included open-ended comments. A few were comments about the tool itself (‘Very helpful to get started with’, ‘Clear explanation and feedback on each area of evaluation’). However, most were evaluative comments for the participants. Nurses recorded both praise (‘Well-received report/Excellent questions’) and constructive criticism. Negative feedback was provided both to experienced nurses (‘As seasoned nurse should have had a few more clinical questions’) and to inexperienced nurses (‘Scattered report’). Of note, comments captured aspects of professionalism (‘Nurse seemed anxious to finish, had to go home’) in addition to feedback about the content and organisation of report.

The comments highlighted the utility of a structured handoff evaluation in assessing both individual skills and system adequacies. For instance, in this comment, the evaluator not only noted weaknesses of an inexperienced nurse, but identified a broader system failure in terms of lack of supervision:

Left out a few clinical items. Did not articulate plan of care surrounding a couple of clinical issues. *RN is still on orientation. Preceptor did not listen to report.

Finally, the comments illustrated both the potential for error and the potential for error-capture of the handoff activity:

Overall poor report. Left out major pieces of information. Not up to date on orders – including DNR/DNI not in as it should be – recipient picked this up.

Discussion

As increasing attention is being paid to communication skills and handoff competencies, the need for tools to evaluate handoff skills is growing. A handoff evaluation tool is necessary for assessing staff competency, testing the effect of handoff improvements, determining sustainability of interventions and identifying systematic barriers and gaps in the handoff process. However, tools should be validated prior to widespread use. This validation study was designed to assess construct validity and inter-rater reliability of a new evaluation tool, the Handoff CEX. The tool is designed to be independent of clinical setting and to be used either for nurses or physicians.

In this study, handoff evaluations were conducted both by external observers – experienced nurse educators or nurse managers – and by the handoff participants. As is common with evaluation tools, we noted a clustering of scores towards the higher end of the score range. In an a priori effort to keep the score range wide, we provided descriptive anchors for high and low scores as part of the tool. One approach to increase the spread of scores might be to add descriptive anchors to the middle of the range, to help evaluators distinguish satisfactory from exemplary performance (French-Lazovik & Gibson 1984, Weng 2004). We will explore this possibility in future studies. Another means of increasing the spread of scores would be to formally train users in use of the tool, perhaps by having them view standardised videos of handoff encounters (Holmboe et al. 2003, 2004). However, videos are cumbersome and useful primarily in a research context, while other educational training sessions have not been found to be effective (Cook et al. 2009).

Although scores were generally high, we found that the external observer scores were consistently lower than peer evaluations. Similarly, other studies have found peers to be more lenient than faculty (Hay 1995, Rudy et al. 2001) or that peer evaluations may differ in their approach from faculty ratings (Kegel-Flom 1975, Risucci et al. 1989). In fact, although several peer evaluation tools exist for physicians, concern has been raised about their validity (Norcini 2003, Evans et al. 2004). In this study, we postulate several potential reasons for the differences between faculty and peer reviews in addition to the possibility that peers are influenced by their personal relationships with the evaluatees. First, all external observers were highly experienced clinicians and may have been better able to discriminate between high- and low-quality handoffs than participants, most of whom had less experience. Second, as nurse educators, they are also trained in evaluation techniques apart from this tool and may therefore have been better primed to provide a range of scores. Third, their sole job was to evaluate the handoff, as opposed to participants, who had to concentrate on the actual handoff as well as to consider it critically from a quality perspective. Thus, although it would be feasible to use this tool solely in a peer evaluation context, it will likely prove to be preferable to be completed by an external observer.

We found a high degree of correlation between individual domains of the handoff CEX except setting. Very similar results were found in the validation of the mini-CEX on which this tool is based (Norcini et al. 1995, 2003). This may be due to an inability of evaluators to distinguish among domains, a ‘halo effect’ where high competence in one dimension spills over into scores given for other dimensions and/or intrinsic correlation of these communication skills. Regardless, as this tool is intended both as an evaluation method and as a means of continuing education (by specifying and reinforcing components of good communication), we elected to retain all domains in the final tool. The weighted kappa for individual domains was fair to moderate, as would be expected from a single observation by a wide variety of types of observers with no specific training in the tool. Similar scores have been found in studies of the mini-CEX (Norcini et al. 1995, 2003, Cook & Beckman 2009, Cook et al. 2009) and other evaluation tools (Kogan et al. 2009). For this reason, we do not recommend single use of the Handoff CEX. As noted in studies of the mini-CEX, repeated observations generate more reliable data (Norcini et al. 1995, 2003). Given the ease and brevity of this evaluation (seven minutes per evaluation), it would be feasible to obtain multiple observations of the same provider over time for a more reliable assessment of competency. In addition, we expect that the kappa score was reduced because we compared peer evaluators with experienced nurse educators and peer evaluators provided systematically higher scores. Our findings suggest that in future a consistent type of evaluator should be employed (Borman 1974).

Our study had several limitations. There is no ‘gold standard’ of handoff quality so we could not determine whether, for instance, external evaluators were systematically over-harsh or peer evaluators over-lenient. We did not correlate scores on the handoff CEX to actual clinical outcomes such as problems with the handover. This study was conducted only on nurses. However, we have successfully used the tool for medical students (Farnan et al. 2010) and are currently studying its use in house staff and hospitalist physicians. Finally, this study was not designed to assess test–retest reliability: the likelihood the same observer would give the same report the same score on two separate occasions. These will be necessary follow-up activities to fully validate the tool for widespread use.

Conclusion

We designed a brief, structured report evaluation tool that was well received by participants, was felt to be easy to use without training, provided data about a wide range of communication competencies and discriminated well between experienced and inexperienced clinicians. The tool also provided an opportunity for evaluators to identify systems failures impeding the handoff process.

Relevance to clinical practice

The Handoff CEX may prove useful for healthcare organisations seeking to measure and improve the quality of handoff communication. In addition, it may be used by nurse educators to frame initial training in handoff skills and by nurse managers to conduct ongoing assessment and feedback of handoff skills among practicing nurses.

Acknowledgments

Development and evaluation of the sign-out CEX are supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R03HS018278-01). At the time this study was conducted, Dr. Horwitz was supported by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR024139 and KL2 RR024138 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Horwitz is currently supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr. Horwitz is also a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). No funding source had any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, the NIH, the NCATS, the AHRQ or AFAR.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Study design: LIH, JD, JMF, JKJ, VMA; data collection and analysis: LIH, JD, TEM and manuscript preparation: LIH, JD, TEM, JMF, JFJ, VMA.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Leora I Horwitz, Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale-New Haven Hospital, and Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Janet Dombroski, Center for Professional Practice Excellence, Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, CT.

Terrence E Murphy, Section of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Jeanne M Farnan, Section of Hospital Medicine, Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Julie K Johnson, Centre for Clinical Governance Research, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Vineet M Arora, Section of Hospital Medicine, Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- Pass the baton or NUTS for safer handoff. Healthcare Risk Management. 2007;29:115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. [accessed 28 August 2010];Proposed Standards for Common Program Requirements. 2010 Available: http://acgme-2010standards.org/pdf/Proposed_Standards.pdf.

- Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman and Hall; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado K, Lee R, Christoffersen E, Fram N, Boblin S, Poole N, Lucas J, Forsyth S. Transfer of accountability: transforming shift handover to enhance patient safety. Healthcare Quarterly. 2006;9:75–79. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2006.18464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CD, Mangino RR. Nurse shift report: who says you can’t talk in front of the patient? Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2006;30:112–122. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony MK, Preuss G. Models of care: the influence of nurse communication on patient safety. Nursing Economics. 2002;20:209–215. 248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2005;14:401–407. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora V, Kao J, Lovinger D, Seiden SC, Meltzer D. Medication discrepancies in resident sign-outs and their potential to harm. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:1751– 1755. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0415-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Commission On Safety and Quality In Health Care. [accessed 15 October 2010];OSSIE Guide to Clinical Handover Improvment. 2010 Available: http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/F72758677DAFA15ECA2577530017CFC5/$File/ossie.pdf.

- Australian Medical Association. Safe Handover: Safe Patients. Australian Medical Association; Kingston, ACT: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin L, Mcginnis C. A computer- generated shift report. Nursing Management. 1994;25:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera ML, Conley R, Postell M. A silent report. Nursing Management. 1998;29:66–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach C, Croskerry P, Shapiro M. Profiles in patient safety: emergency care transitions. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:364–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block M, Ehrenworth JF, Cuce VM, Ng’ang’a N, Weinbach J, Saber SB, Milic M, Urgo JA, Sokoli D, Schlesinger MD. The tangible handoff: a team approach for advancing structured communication in labor and delivery. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2010;36:282–287. 241. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borman WC. The rating of individuals in organizations: an alternate approach. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1974;12:105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Borowitz SM, Waggoner-Fountain LA, Bass EJ, Sledd RM. Adequacy of information transferred at resident signout (in-hospital handover of care): a prospective survey. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2008;17:6–10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Medical Association, National Patient Safety Agency & NHS Modernisation Agency. Safe Handover: Safe Patients. British Medical Association; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Calleja P, Aitken LM, Cooke ML. Information transfer for multi-trauma patients on discharge from the emergency department: mixed-method narrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67:4–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair LL, Trussell PM. Nursing service. The change of shift report: study shows weaknesses, how it can be improved. Hospitals. 1969;43:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Does scale length matter? A comparison of nineversus five-point rating scales for the mini-CEX. Advances in Health Sciences Education Theory and Practice. 2009;14:655–664. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DA, Dupras DM, Beckman TJ, Thomas KG, Pankratz VS. Effect of rater training on reliability and accuracy of mini-CEX scores: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:74–79. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0842-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox SS. Taping report: tips to record by. Nursing. 1994;24:64. doi: 10.1097/00152193-199403000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebright PR, Urden L, Patterson E, Chalko B. Themes surrounding novice nurse near-miss and adverse-event situations. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2004;34:531–538. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman I, Segesten K. Deputed power of medical control: the hidden message in the ritual of oral shift reports. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995;22:1006–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1995.tb02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Review of instruments for peer assessment of physicians. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:1240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7450.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnan JM, Paro JA, Rodriguez RM, Reddy ST, Horwitz LI, Johnson JK, Arora VM. Hand-off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand-off experience (OSHE) Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1170-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French-Lazovik G, Gibson CL. Effects of verbally labeled anchor points on the distributional parameters of rating measures. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1984;8:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi TK. Fumbled handoffs: one dropped ball after another. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;142:352–358. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, Lipsitz SR, Rogers SO, Zinner MJ, Gawande AA. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007;204:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J. SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2006;32:167– 175. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JA. Tutorial reports and ratings. In: Shannon S, Nocterm G, editors. Evaluation Methods: A Resource Handbook. McMaster University; Hamilton, ON: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hays MM. An exploratory study of supportive communication during shift report. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;3(3) [Google Scholar]

- Hohenhaus S, Powell S, Hohenhaus JT. Enhancing patient safety during hand-offs: standardized communication and teamwork using the ‘SBAR’ method. American Journal of Nursing. 2006;106:72A–72B. [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe ES, Huot S, Chung J, Norcini J, Hawkins RE. Construct validity of the miniclinical evaluation exercise (miniCEX) Academic Medicine. 2003;78:826–830. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe ES, Hawkins RE, Huot SJ. Effects of training in direct observation of medical residents’ clinical competence: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:874–881. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:1755–1760. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagsi R, Kitch BT, Weinstein DF, Campbell EG, Hutter M, Weissman JS. Residents report on adverse events and their causes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:2607–2613. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare. Focus on five. Strategies to improve hand-off communication: implementing a process to resolve questions. Joint Commission Perspectives on Patient Safety. 2005;5:11. [Google Scholar]

- Kegel-Flom P. Predicting supervisor, peer and self ratings of intern performance. Journal of Medical Education. 1975;50:812–815. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197508000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr MP. A qualitative study of shift handover practice and function from a socio-technical perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37:125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitch BT, Cooper JB, Zapol WM, Marder JE, Karson A, Hutter M, Campbell EG. Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34:563– 570. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:1316–1326. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally S. An investigation into the functions of nurses’ communication at the inter-shift handover. Journal of Nursing Management. 1999;7:29–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.1999.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LH, Levine JA, Schultz HJ. Utility of a standardized sign-out card for new medical interns. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11:753–755. doi: 10.1007/BF02598991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. Ensuring continuing care: styles and efficiency of the handover process. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;16:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcini JJ. Peer assessment of competence. Medical Education. 2003;37:539–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Arnold GK, Kimball HR. The mini-CEX (clinical evaluation exercise): a preliminary investigation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1995;123:795–799. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Duffy FD, Fortna GS. The mini-CEX: a method for assessing clinical skills. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138:476–481. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-6-200303180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine LA, Millman A. Sealing the cracks, not falling through: using handoffs to improve patient care. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 2009;25:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J, Coiera E. Improving clinical communication: a view from psychology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2000;7:453–461. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J, Gardner G, Wiltshire J. Handover: the collective narrative of nursing practice. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1992;9:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson ES, Roth EM, Woods DD, Chow R, Gomes JO. Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2004;16:125– 132. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothier D, Monteiro P, Mooktiar M, Shaw A. Pilot study to show the loss of important data in nursing handover. British Journal of Nursing. 2005;14:1090–1093. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.20.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2009;24:196–204. doi: 10.1177/1062860609332512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenberg LA, Leisch J, Cunningham JM. Nursing handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. American Journal of Nursing. 2010;110:24–34. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000370154.79857.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risucci DA, Tortolani AJ, Ward RJ. Ratings of surgical residents by self, supervisors and peers. Surgical Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1989;169:519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy DW, Fejfar MC, Griffith CH, 3rd, Wilson JF. Self- and peer assessment in a first-year communication and interviewing course. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2001;24:436–445. doi: 10.1177/016327870102400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno SM, Arnett MV, Domanski JP. Standardized sign-out reduces intern perception of medical errors on the general internal medicine ward. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2009;21:121–126. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder SJ. Picking up the PACE: a new template for shift report. Nursing. 2006;36:22–23. doi: 10.1097/00152193-200610000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton A, Chan C, Elliott M, Stuart J, Jayasuriya R, Crookes P. Nursing handovers: do we really need them? Journal of Nursing Management. 2004;12:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharit J, Mccane L, Thevenin DM, Barach P. Examining links between signout reporting during shift changeovers and patient management risks. Risk Analysis. 2008;28:969–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. Inter-shift report: oral communication using a quality assurance approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 1993;2:266–267. [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. 2010 Hospital Accreditation Standards. Joint Commission Resources; Oakbrook Terrace, IL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh CA, Flanagan ME, Ebright P. Barriers and facilitators to nursing handoffs: recommendations for redesign. Nursing Outlook. 2010;58:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng L-J. Impact of the number of response categories and anchor labels on coefficient alpha and test-retest reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004;64:956–972. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Collaborating centre for patient safety solutions. Communication during patient hand-overs. Patient Safety Solutions. 2007;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MJ. A template for safe and concise handovers. Medsurg Nursing: Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses. 2007;16:201–206. 200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]