Abstract

Spraying mustard (Sinapis alba L.) seedlings with salicylic acid (SA) solutions between 10 and 500 μm significantly improved their tolerance to a subsequent heat shock at 55°C for 1.5 h. The effects of SA were concentration dependent, with higher concentrations failing to induce thermotolerance. The time course of thermotolerance induced by 100 μm SA was similar to that obtained with seedlings acclimated at 45°C for 1 h. We examined the hypothesis that induced thermotolerance involved H2O2. Heat shock at 55°C caused a significant increase in endogenous H2O2 and reduced catalase activity. A peak in H2O2 content was observed within 5 min of either SA treatment or transfer to the 45°C acclimation temperature. Between 2 and 3 h after SA treatment or heat acclimation, both H2O2 and catalase activity significantly decreased below control levels. The lowered H2O2 content and catalase activity occurred in the period of maximum thermoprotection. It is suggested that thermoprotection obtained either by spraying SA or by heat acclimation may be achieved by a common signal transduction pathway involving an early increase in H2O2.

Plants have evolved various ways of coping with their changing surroundings. Adaptive responses are directly regulated by genetic and biochemical characteristics, which may be manipulated. An understanding of the biochemical changes involved in plant-stress responses will enable the development of genetically engineered plant material with enhanced resistance to biotic and abiotic stress. Because high temperature is one of the major abiotic stresses limiting plant yield and distribution in many regions of the world (Ong and Baker, 1985; Criddle et al., 1994), it has been the focus of much research, particularly since the discovery and characterization of HSPs. The heat-shock response is not unique to plants and has been described for a wide range of organisms, including bacteria (Vierling, 1991). In cyanobacteria oxidative stress can induce the synthesis of some HSPs (Mittler and Tel-Or, 1991), suggesting that HSPs and oxidative stress-induced proteins may share one or several common regulatory operons (Lee et al., 1983; Van Bogelen et al., 1987). However, to date very little research has been undertaken to elucidate the nature of the common responses to heat shock and oxidative stress in plants.

In recent years SA has been the focus of much attention because of its ability to induce protection against plant pathogens (Raskin, 1992). However, the mode of action of SA during pathogenesis and its role in the transient increase of active oxygen species, including H2O2, characteristic of incompatible plant-pathogen interactions (the oxidative burst), is still a matter for debate (Levine et al., 1994; Ryals et al., 1995). The in vitro inhibition of catalase (Chen et al., 1993; Sanchez-Casas and Klessig, 1994; Conrath et al., 1995) and ascorbate peroxidase by SA (Durner and Klessig, 1995) provided the first indications of the existence of a link between SA and the oxidative burst. Other workers, however, suggest that catalase inhibition may not be the main mechanism by which SA induces H2O2 accumulation (Rüffer et al., 1995; Ryals et al., 1995). A direct role for SA in potentiating H2O2 production by a plasma membrane NAD(P)H oxidase has been proposed (Kauss and Jeblick, 1995, 1996; Willekens et al., 1995; Mur et al., 1996; Shirasu et al., 1997). In addition, H2O2 may regulate SA accumulation (Bi et al., 1995; León et al., 1995; Neuenschwander et al., 1995; Summermatter et al., 1995).

Generation of active oxygen species, particularly H2O2, during abiotic stresses has also been proposed as part of the signaling cascade leading to protection from these stresses (Doke et al., 1994; Prasad et al., 1994; Foyer et al., 1997). SA also accumulates during exposure to ozone or UV light (Yalpani et al., 1994; Sharma et al., 1996), whereas pretreatment of leaves with SA can protect them from paraquat-induced oxidative stress (Strobel and Kuc, 1995). Therefore, it is interesting to explore whether SA and H2O2 may be involved in the induction of protective mechanisms involved in tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses.

Tissues from potato (Solanum tuberosum) microplants grown on acetylsalicylic acid in our laboratory were shown to have enhanced thermotolerance (Lopez-Delgado et al., 1998). The following experiments were designed to determine whether SA could also induce thermotolerance in whole seedlings. Thermoprotection was induced by spraying SA and was compared with heat acclimation. Tissue H2O2 contents and catalase activities were determined to assess their possible involvement in induced thermotolerance.

Materials and Methods

Mustard (Sinapis alba L.) seeds (Kings Seeds, Essex, UK) were germinated in Levington's Universal compost (Fisons, Ipswich, UK) (15 seedlings per 15- × 21-cm tray) and grown for 8 d in a growth room with RH at 70% under a 16-h photoperiod on a 24/18°C day/night cycle at 100 μmol m−2 s−1 PAR.

Treatments

Plants were sprayed with a range (1 μm–1 mm) of SA (Sigma) concentrations. All spray solutions, including water controls, were adjusted to pH 7.0 with KOH. For acclimation treatments, plants were exposed to a nonlethal temperature (air temperature 45°C) for 1 h in the dark. To induce heat shock, plants were exposed to 55°C (air temperature) for 1.5 h in the dark.

Assessment of Heat Tolerance

Survival was assessed by the capacity of the seedlings to grow after the heat-shock treatment. Thermotolerance was assessed from the percentage survival in each sample of 10 to 15 plants, 10 d after heat shock. Seedling death was characterized by stem collapse 1 to 2 cm below the apex. Surviving plants often showed signs of damage such as leaf bleaching but their apices and stems remained green.

Measurement of H2O2

H2O2 was determined by measuring luminol-dependent chemiluminescence following a modification of the method described by Warm and Laties (1982) and Chen et al. (1993).

Plant tissue (approximately 0.5 g), consisting of the apical region of the shoot including the cotyledons, was ground in liquid N2 and extracted in 3 mL of ice-cold 5% TCA (Fisher Scientific). The crude extracts were centrifuged for 20 min at 1400g. A sample of supernatant (0.5 mL) was passed through a column containing 0.5 g of Dowex resin (1X1–100, chloride form, 1% cross-linked, Sigma) previously equilibrated with 5% TCA. The column was washed with a further 3.5 mL of 5% TCA; all eluates were collected together. H2O2 content was measured by adding 0.5 mL of eluate to 0.5 mL of 0.5 mm luminol (Aldrich) and the volume was made to 5.5 mL with 0.2 m NH4OH (pH 9.0). This mixture (0.5 mL) in a borosilicate glass tube (6 × 50 mm, Laboratory Sales, Ltd., Rochdale, UK) was analyzed using a chemiluminescence meter (model A6100, Pico-Lite Luminometer Analyzer, Packard, Meriden, CT). Chemiluminescence was initiated by injecting 50 μL of 0.5 mm potassium ferricyanide (Sigma) in 0.2 m NH4OH. The emitted photons were counted for 5 s. Recovery estimates (which consisted of adding a known concentration of H2O2 to aliquots of the initial extracts that were then processed in parallel) indicated that on average 93% (sd = 2.5%; n = 38) of the H2O2 was recovered, and were used as correction factors for each sample (Warm and Laties, 1982).

Catalase Activity

Catalase activity was determined by measuring the rate of H2O2 conversion to O2 at room temperature using a liquid-phase O2 electrode (Hansatech, Norfolk, UK). Approximately 0.5 g of plant tissue, consisting of the apical region of the shoot including the cotyledons, was extracted in 1.5 mL of 0.1 mm Hepes/KOH buffer (pH 7.4) and then centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min. The rate of O2 production was measured by adding 50 μL of the supernatant to 0.1 m Hepes (pH 7.4) containing 530 mm H2O2. Catalase activity was calculated on a fresh weight basis to keep the data uniform with the H2O2 measurements, and to reduce the chances of distortion as a result of protein synthesis alteration due to heat shock (Vierling, 1991; Bettany, 1995).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were analyzed by χ2 contingency tables and continuously variable data by analysis of variance and Student's t test. Significance tests were performed on the combined results of at least four replicated experiments (each replicate involved 12–15 seedlings) for survival data and at least two replicated experiments (each experiment involved three separate samples of ≥ 3 seedlings) for biochemical measurements. In the figures se bars show variation from the means of replicated experiments for survival data (n ≥ 4) or the combined results for biochemical measurements (n ≥ 6).

RESULTS

Effects of Heat Acclimation and SA on Survival from Heat Shock

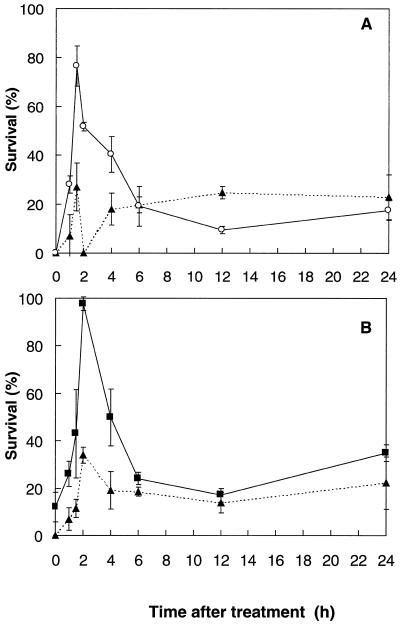

Enhanced tolerance of mustard seedlings to heat shock (1.5 h at 55°C) was obtained either by spraying with 100 μm SA at 24°C or by prior high-temperature acclimation (1 h at 45°C). The period of protection from 1.5 to 4 h following these treatments was similar for both SA spray and heat acclimation (Fig. 1, A and B).

Figure 1.

A, Percentage survival of mustard seedlings heat shocked at various times after spraying with 100 μm SA (○) or with water (▴) at 24°C. B, Percentage survival of mustard seedlings heat shocked at various times after 1 h of acclimation treatment (45°C) in the dark (▪); controls (▴) were kept at 24°C during the acclimation period (light- or dark-incubated controls were not significantly different). Bars represent se of at least four experiments (n ≥ 4), each with 12 to 15 seedlings.

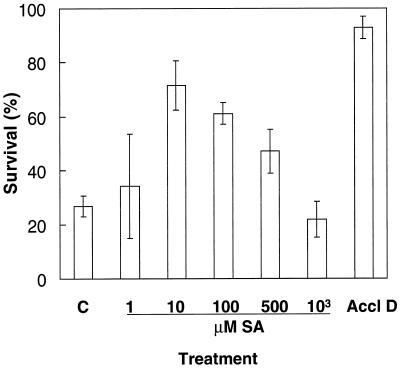

A period of 1.5 h after spraying was adopted for assessment of the concentration dependence of the SA treatments (Fig. 2). SA solutions between 10 to 500 μm significantly increased (P < 0.007) thermotolerance to heat shock in comparison with controls sprayed with water (Fig. 2). In contrast, spraying with SA concentrations of 1 μm or 1 mm did not improve survival of heat shock (Fig. 2). By comparison, the heat-acclimation treatment shown in Figure 2, consisting of 1 h at 45°C in the dark followed by a 1-h recovery period in the light, increased survival of heat shock by 4-fold compared with nonacclimated plants.

Figure 2.

Percentage survival of mustard seedlings heat shocked for 1.5 h at 55°C either 1.5 h after spraying with water (C) or various concentrations of SA at 24°C, or 1 h after acclimation (1 h at 45°C) in the dark (Accl D). Bars represent se of at least four experiments (n ≥ 4), each with 12 to 15 seedlings.

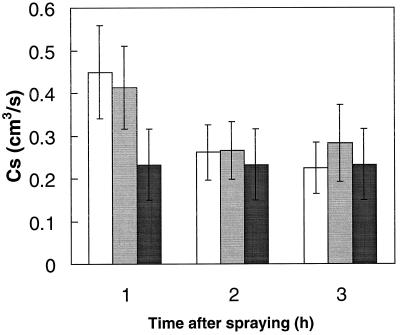

SA can affect stomatal opening under certain conditions (Larque-Saavedra, 1979; Rai et al., 1986). Cs measurements were therefore made to examine whether changes in Cs could have been responsible for the observed thermoprotection of SA-sprayed plants (Fig. 3). Spraying with either H2O or 100 μm SA solution increased Cs during the next hour (probably because of increased humidity at the leaf surface), but Cs then decreased back to levels of nonsprayed control plants after 2 h. There were no significant differences in Cs between plants sprayed with either water or SA (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Cs of mustard seedlings at intervals following spraying with either distilled water (white bars) or with 100 μm SA solution (gray bars) in comparison with nonsprayed controls (black bars) (n = 8).

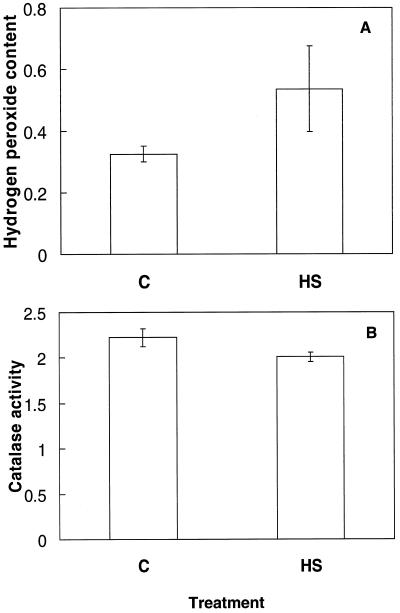

Effects of Heat Shock on H2O2 Content and Catalase Activity

H2O2 and catalase were measured to determine whether heat shock caused oxidative stress in this system. Subjecting mustard seedlings to 55°C for 1.5 h in the dark significantly (P < 0.05) increased the level of endogenous H2O2 by over 65% in comparison with control plants grown at 24°C (Fig. 4A). The change in fresh weight between heat-shocked and control plants at the time of extraction did not exceed 10%. Catalase activity, calculated on a fresh weight basis, was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) by 9.6% following heat shock (Fig. 4B). Over 80% of the mustard seedlings died within 2 to 3 d of the heat-shock treatment.

Figure 4.

A, H2O2 content (μmol g−1 fresh weight) of mustard seedlings following a 1-h heat-shock treatment in the dark at 55°C. Bars represent the se (n = 9). B, Catalase activity (μmol O2 min−1 g−1 fresh weight) of mustard seedlings following a 1-h heat-shock treatment in the dark at 55°C. Bars represent se (n = 12).

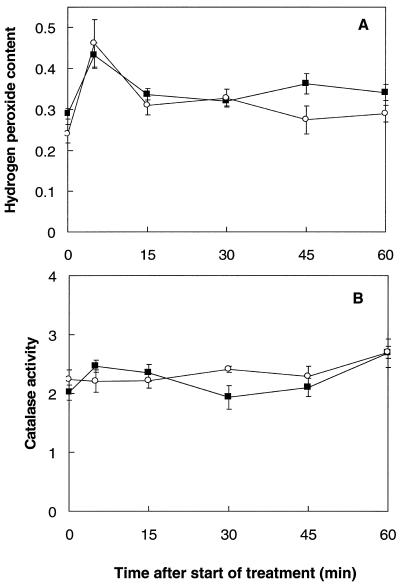

H2O2 Content and Catalase Activity during the 1-h HeatAcclimation Treatment and the 1st h after SA Spray

The H2O2 content of seedlings was measured during the inductive treatments. During a 1-h 45°C acclimation treatment, the H2O2 content increased by over 41% within the first 5 min (Fig. 5A). It then decreased toward the control value over the remainder of the 1-h incubation, but was still significantly (P < 0.05) higher (19–30%) than controls after 15 and 45 min.

Figure 5.

A, H2O2 content (μmol g−1 fresh weight) of mustard seedlings either during the 1st h immediately after spraying with a 100 μm SA solution at 24°C (○), or during a 1-h temperature-acclimation treatment at 45°C (▪). B, Catalase activity (μmol O2 min−1 g−1 fresh weight) of mustard seedlings either during the 1st h immediately after spraying with a 100 μm SA solution at 24°C (○), or during a 1-h temperature-acclimation treatment at 45°C (▪). Bars represent se (n = 8).

The H2O2 content of mustard plants increased by more than 90% 5 min after spraying with a 100 μm SA solution. Fifteen and 30 min after spraying, H2O2 levels were still significantly (P < 0.05) higher (28–35%) than in the control plants. After 45 min the H2O2 content had returned to control values. Thus, both SA and heat acclimation caused a rapid increase in H2O2, which then declined toward control values.

Catalase activity was determined during the 1-h acclimation treatment and during the 1st h following the SA spray. In both cases the catalase activity fluctuated but was significantly increased (P < 0.05) after 60 min (Fig. 5B).

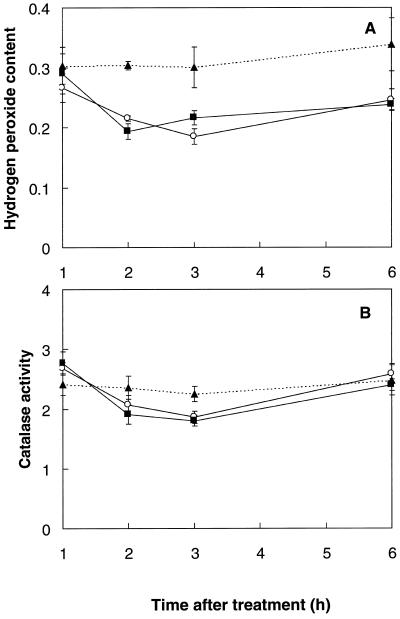

H2O2 Content and Catalase Activity during the Period of Thermotolerance

Since both SA and heat acclimation induced significant thermoprotection from 1.5 to 4 h following treatment (Fig. 1, A and B), measurements of H2O2 and catalase were undertaken during this period. One hour after either SA spray or return of the seedlings to optimal growth temperatures (24°C) after heat acclimation, endogenous H2O2 was not significantly different from that of the control plants (Fig. 6A). However, 2 and 3 h after treatment the H2O2 content was more than 25% lower (P < 0.05) in both acclimated and SA-sprayed plants. After 6 h the level of endogenous H2O2 in SA-sprayed and acclimated plants was increasing toward control values. Thus, thermotolerance elicited by both treatments coincided with a significant decrease in tissue H2O2 content.

Figure 6.

A, H2O2 content (μmol g−1 fresh weight) of mustard seedlings during the thermoprotection period following either spraying with a 100 μm SA solution at 24°C (○), or a 1-h temperature-acclimation treatment (45°C) in the dark (▪). Controls (▴) were kept at 24°C without spraying (light- or dark-incubated controls were not significantly different). Bars represent se (n = 8). B, Catalase activity (μmol O2 min−1 g−1 fresh weight) of mustard seedlings during the thermoprotection period following either spraying with a 100 μm SA solution (○) at 24°C, or a 1-h temperature-acclimation treatment (45°C) in the dark (▪). Controls (▴) were kept at 24°C without spraying (light- or dark-incubated controls were not significantly different). Bars represent se (n ≥ 8).

Catalase activity was determined during the same period (Fig. 6B). Both treatments resulted in a significant (P < 0.032), transient decrease in extractable catalase activity of more than 15% 2 to 3 h after treatment, followed by an increase back to control levels by 6 h. Catalase activity was therefore significantly lower during the period of thermotolerance; the decreased catalase activity was not due to co-extracted SA, because there was no inhibition when SA concentrations up to 10 mm were added to the in vitro assay.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of thermoprotection obtained by spraying SA on seedlings. The increased thermotolerance obtained following spraying mustard seedlings with SA solutions (Fig. 2) extends our recent observation that tissues of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) microplants grown on culture medium containing low concentrations of acetylsalicylic acid were more thermotolerant than tissues of microplants grown on acetylsalicylic acid-free medium (Lopez-Delgado et al., 1998). Thermoprotection obtained in SA-treated mustard seedlings was temporary, being maximal from 1.5 to 4 h after spraying (Fig. 1A). Heat-acclimation treatment also gave effective protection over the same time period (Fig. 1B). Howarth and Skøt (1994) found that sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) seedlings were significantly more thermotolerant 2 and 4 h after a 2-h 45°C acclimation treatment, but thermotolerance was completely lost by 6 h.

Exogenous applications of SA, either by direct injection or by spraying, have been reported to cause a multitude of effects on the morphology and physiology of plants (Raskin, 1992; Pierpoint, 1994; Pancheva et al., 1996). SA is known to affect stomatal opening (Larque-Saavedra, 1979; Rai et al., 1986). However, in this study no significant effect of SA on Cs was observed during the first 3 h following application (Fig. 3), which is similar to previous observations in barley (Pancheva et al., 1996). Stomatal regulation was therefore probably not involved in the acquired thermotolerance following spraying with a SA solution.

If heat shock generates oxidative stress, SA may mimic temperature acclimation by also generating H2O2. It has been suggested that heat shock may produce oxidative stress in plant cells, as well as in human and in animal cells (Lee et al., 1983; Privalle and Fridovich, 1987; Bowler et al., 1992), although evidence of H2O2 accumulation during heat shock was only recently reported in cell-suspension cultures (Doke et al., 1994) and in planta in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) seedlings (Foyer et al., 1997). Indirect evidence linking oxidative stress and heat shock has often combined high light and heat shock, resulting in photoinhibition and/or photooxidation (Tsang et al., 1991; Bowler et al., 1992). The present study clearly indicates that heat shock can result in increased oxidant accumulation in plants (Fig. 4A), even when applied in the dark. H2O2 accumulation after heat shock in the dark is probably independent of photosynthesis and may be produced in a manner similar to H2O2 in plants chilled and acclimated in the dark (Okuda et al., 1991; Purvis and Shewfelt, 1993; Prasad et al., 1994), where the site of H2O2 synthesis is unresolved. The increase in H2O2 following heat shock in the dark could be explained by the model of Doke et al. (1994; Doke, 1997) in which abiotic stresses are accompanied by an oxidative burst, similar to that involved in signaling during plant-pathogen interactions (Levine et al., 1994; Mehdy, 1994; Baker and Orlandi, 1995).

Although H2O2 increased by over 65% following a 1-h heat shock in mustard seedlings, catalase activity decreased by about 10% (Fig. 4). There are several reports of decreased activities of key antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and catalase) following heat shock; the antioxidant defenses may thus be impaired by heat shock and lead to increased oxidant concentrations (Matters and Scandalios, 1986; Feierabend et al., 1992; Streb et al., 1993; Willekens et al., 1995; Foyer et al., 1997; Polle, 1997). Such perturbations in oxidant concentrations may be a prerequisite for redox signaling-induced changes in gene expression (Foyer et al., 1997). Heat shock suppresses translation of many proteins, except HSPs (Vierling, 1991). As catalase has a rapid turnover, conditions inhibiting catalase synthesis will lower the steady-state level of this enzyme (Streb et al., 1993; Streb and Feierabend, 1996; Scandalios et al., 1997). Thus, heat shock and oxidative stress will enhance inactivation of catalase by preventing synthesis of new enzyme (Hertwig et al., 1992; Feierabend and Dehne, 1996), resulting in a decline in catalase activity. Because the heat shock was applied in the dark, catalase photoinactivation (Feierabend and Engel, 1986; Polle, 1997) is not the cause of the reduction in catalase activity in the present study (Fig. 4B).

H2O2 increased during heat acclimation and following SA treatment. An increase in H2O2 content was measured 5 min after the start of the heat acclimation and after the SA spray treatments (Fig. 5A). This early peak in H2O2 is similar to that observed by Doke et al. (1994) during heat shock of cell suspensions. The amplitude of the H2O2 increase is also similar to that reported by Chen et al. (1993), following a continuous 24-h injection of a 1 mm SA solution into petioles of tobacco plants. It is tempting to associate this H2O2 increase with an oxidative burst similar to that observed during other forms of abiotic stress (Shimada et al., 1991; Doke et al., 1994; Sgherri et al., 1996; Sharma et al., 1996), including chilling (Omran, 1980; Okuda et al., 1991; Prasad et al., 1994), and during incompatible pathogen interactions (Apostol et al., 1989; Chen et al., 1993; Doke et al., 1994; Tenhaken et al., 1995). Recent work by Lopez-Delgado et al. (1998) also implicates H2O2 in the signal transduction sequence inducing thermotolerance, since tissues of potato microplants grown from explants incubated with H2O2 showed enhanced thermotolerance. The increase in H2O2 during temperature acclimation and immediately following SA spray (Fig. 5A) may thus be part of the signaling cascade involved in inducing protection against a subsequent stress.

The biochemical changes responsible for the transient period of induced thermoprotection (Fig. 1) are of considerable interest, as they may be manipulated to enhance thermotolerance in plants. The metabolic and molecular mechanisms associated with the observed decline in H2O2 content and in catalase activity during this period (Fig. 6) are unknown, but the parallel changes in the acclimated and SA-treated plants suggest that these parameters may be relevant to thermotolerance. The decline in H2O2 content may be indicative of an enhanced antioxidant potential in the tissues, which would contribute to enhanced thermotolerance. Catalase activity reached a minimum during the thermoprotection period following either treatment (Fig. 6B), although its activity was higher at the start of this period (Figs. 5B and 6B). Other antioxidants such as GSH may prove to be involved during high-temperature acclimation, as observed by Nieto-Sotelo and Ho (1986) during heat shock. Although SA can inhibit catalase and ascorbate peroxidase in vitro (Chen et al., 1993; Conrath et al., 1995; Durner and Klessig, 1995; Rüffer et al., 1995), this mechanism would not explain the lower catalase activity extracted from our SA-treated mustard plants. It may also be worth investigating possible links between the thermotolerance induced with SA and the role of this compound in thermogenicity (Raskin et al., 1987; Van der Straeten et al., 1995).

In conclusion, the present study shows that SA treatment induces thermoprotection in mustard seedlings, and that the period of induced thermoprotection is similar to that obtained by heat acclimation. Both the SA and heat-acclimation treatments induced a transient initial increase in H2O2, but both resulted in decreased H2O2 and catalase contents during the period of induced thermoprotection. Since SA and H2O2 have recently been shown to induce thermoprotection in potato microplants (Lopez-Delgado et al., 1998), we suggest that both SA and H2O2 could be involved in signal transduction leading to acclimation during heat stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for technical advice from Dr. A. Kingston-Smith and Prof. J. Barrett.

Abbreviations:

- Cs

stomatal conductance

- HSP

heat-shock protein

- SA

salicylic acid

Footnotes

H.L.-D. was financially supported by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia, the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales y Agropecuarias, and the British Council.

LITERATURE CITED

- Apostol I, Heinstein PF, Low PS. Rapid stimulation of an oxidative burst during elicitation of cultured plant cells. Role in defense and signal transduction. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:109–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CJ, Orlandi EW. Active oxygen species in plant pathogenesis. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1995;33:299–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.33.090195.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettany AJE. Stress responses in cell cultures of Lolium temulentum. I. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional changes in gene expression during heat shock and recovery. J Plant Physiol. 1995;146:162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bi YM, Kenton P, Mur L, Darby R, Draper J. Hydrogen peroxide does not function downstream of salicylic acid in the induction of PR protein expression. Plant J. 1995;8:235–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08020235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Montagu MV, Inzé D. Superoxide dismutase and stress tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Silva H, Klessig RF. Active oxygen species in the induction of plant systemic acquired resistance by SA. Science. 1993;262:1883–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.8266079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U, Chen ZX, Ricigliano JR, Klessig DF. Two inducers of plant defense responses, 2,6-dichloroisionicotinic acid and salicylic acid, inhibit catalase activity in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7143–7147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criddle RS, Hopkin MS, McArthur ED, Hansen LD. Plant distribution and the temperature-coefficient of metabolism. Plant Cell Env. 1994;17:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Doke N. The oxidative burst: roles in signal transduction and plant stress. In: Scandalios J, editor. Oxidative Stress and the Molecular Biology of Antioxidant Defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 785–813. [Google Scholar]

- Doke N, Miura Y, Leandro MS, Kawakita K. Involvement of superoxide in signal transduction: responses to attack by pathogens, physical and chemical shocks, and UV radiation. In: Foyer CH, Mullineaux PM, editors. Causes of Photooxidative Stress and Amelioration of Defense Systems in Plants. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Durner J, Klessig DF. Inhibition of ascorbate peroxidase by salicylic-acid and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, 2 inducers of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11312–11316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feierabend J, Dehne S. Fate of the porphyrin cofactors during the light-dependent turnover of catalase and of the photosystem II reaction-center protein D1 in mature rye leaves. Planta. 1996;198:413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Feierabend J, Engel S. Photoinactivation of catalase in vitro and in leaves. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;251:567–576. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feierabend J, Schaan C, Hertwig B. Photoinactivation of catalase occurs under both high- and low-temperature stress conditions and accompanies photoinhibition of photosystem II. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1554–1561. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Lopez-Delgado H, Dat JF, Scott IM. Hydrogen peroxide- and glutathione-associated mechanisms of acclimatory stress tolerance and signaling. Physiol Plant. 1997;100:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig B, Streb P, Feierabend J. Light dependence of catalase synthesis and degradation in leaves and the influence of interfering stress conditions. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1547–1553. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth CJ, Skøt K. Detailed characterisation of heat shock synthesis and induced thermotolerance in seedlings of Sorghum bicolor L. J Exp Bot. 1994;45:1353–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Kauss H, Jeblick W. Pre-treatment of parsley suspension cultures with salicylic acid enhances spontaneous and elicited production of H2O2. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1171–1178. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauss H, Jeblick W. Influence of salicylic acid on the induction of competence for H2O2 elicitation. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:755–763. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larque-Saavedra A. Stomatal closure in response to acetylsalicylic acid treatments. Z Pflanzenphysiol. 1979;93:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Lee PC, Bochner BR, Ames BN. AppppA, heat-shock stress, and cell oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7496–7500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León J, Lawton MA, Raskin I. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates salicylic acid biosynthesis in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1673–1678. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Tenhaken R, Dixon R, Lamb C. H2O2 from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;79:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Delgado H, Dat JF, Foyer CH, Scott IM (1998) Induction of thermotolerance in potato microplants by acetylsalicylic acid and H2O2. J Exp Bot (in press)

- Matters GL, Scandalios J. Effect of the free radical-generating herbicide paraquat on the expressing superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes in maize. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;882:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdy M. Active oxygen species in plant defense against pathogens. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:467–472. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Tel-Or E. Oxidative stress responses and shock proteins in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus R2 (PCC-7942) Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur LAJ, Naylor G, Warner SAJ, Sugars JM, White RF, Draper J. Salicylic acid potentiates defense gene expression in leaf tissue exhibiting acquired to pathogen attack. Plant J. 1996;9:559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander U, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Uknes S, Kessmann H, Ryals J. Is hydrogen peroxide a 2nd messenger of salicylic-acid in systemic acquired resistance? Plant J. 1995;8:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Sotelo J, Ho T-HD. Effect of heat shock on the metabolism of glutathione in maize roots. Plant Physiol. 1986;82:1031–1035. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T, Matsuda Y, Yamanaka A, Sagisaka S. Abrupt increase in the level of hydrogen peroxide in leaves of winter wheat is caused by cold treatment. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1265–1267. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omran RG. Peroxide levels and activities of catalase, peroxidase and indoleacetic acid during and after chilling cucumber seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1980;65:407–408. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CK, Baker NR (1985) Temperature and leaf growth. In NR Baker, WJ Davies, CK Ong, eds, Control of Leaf Growth. Seminar Series, Society for Experimental Biology, No. 27. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 175–200

- Pancheva TV, Popova LP, Uzunova AN. Effects of salicylic acid on growth and photosynthesis in barley plants. Plant Physiol. 1996;149:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pierpoint WS. Salicylic acid and its derivatives in plants: medicines, metabolites and messenger molecules. Bot Res. 1994;20:163–235. [Google Scholar]

- Polle A. Defense against photooxidative damage in plants. In: Scandalios J, editor. Oxidative Stress and the Molecular Biology of Antioxidant Defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 785–813. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad TK, Anderson MD, Martin BA, Stewart CR. Evidence for chilling-induced oxidative stress in maize seedlings and a regulatory role for hydrogen peroxide. Plant Cell. 1994;6:65–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privalle CT, Fridovich I. Induction of superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli by heat shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2723–2726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis AC, Shewfelt RL. Does the alternative pathway ameliorate chilling injury in sensitive plant tissues? Physiol Plant. 1993;88:712–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1993.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai VK, Sharma SS, Sharma S. Reversal of ABA-induced stomatal induced closure by phenolic compounds. J Exp Bot. 1986;37:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I. Role of salicylic acid in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I, Ehmann A, Melander WR, Meeuse BJD. Salicylic acid: a natural inducer of heat production in Arum lilies. Science. 1987;237:1601–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.237.4822.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüffer M, Steipe B, Zenk MH. Evidence against specific binding of salicylic acid to plant catalase. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals J, Lawton KA, Delaney TP, Friedrich L, Kessmann H, Neuenschwander U, Uknes S, Vernooij B, Weymann K. Signal-transduction in systemic acquired resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4202–4205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Casas P, Klessig DF. A salicylic acid-binding activity and a salicylic acid-inhibitable catalase activity are present in a variety of plant species. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1675–1679. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandalios JG, Guan L, Polidoros AN. Catalases in plants: gene structure, properties, regulation, and expression. In: Scandalios J, editor. Oxidative Stress and the Molecular Biology of Antioxidant Defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 343–406. [Google Scholar]

- Sgherri CLM, Pinzino C, Navariizzo F. Sunflower seedlings subjected to increasing stress by water-deficit: changes in O2− production related to the composition of thylakoid membranes. Physiol Plant. 1996;96:446–452. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma YJ, León J, Raskin I, Davis KR. Ozone-induced responses in Arabidopsis thaliana: the role of salicylic acid in the accumulation of defense related transcripts and induced resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Akagi N, Goto H, Watanabe H, Nakanishi M, Yoshimatsu S, Ono C. Free radical production by the red tide alga, Chotonella antigua. Histochem J. 1991;23:361–365. doi: 10.1007/BF01042181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu K, Nakajima H, Rajasekhar VK, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Salicylic acid potentiates an agonist-dependent gain control that amplifies pathogen signals in the activation of defense mechanisms. Plant Cell. 1997;9:261–270. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streb P, Feierabend J. Oxidative stress responses accompanying photoinactivation of catalase in NaCl-treated rye leaves. Bot Acta. 1996;109:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Streb P, Michael-Knauf A, Feierabend J. Preferential photoinactivation of catalase and photoinhibition of photosystem II are common early symptoms under various osmotic and chemical stress conditions. Physiol Plant. 1993;88:590–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1993.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel NE, Kuc A. Chemical and biological inducers of systemic acquired resistance to pathogens protect cucumber and tobacco from damage caused by paraquat and cupric chloride. Phytopathol. 1995;85:1306–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Summermatter K, Sticher L, Matrix J-P. Systemic responses in Arabidopsis thaliana infected and challenged with Pseudomonas syringae pv syringae. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1379–1385. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhaken R, Levine A, Brisson LF, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Function of the oxidative burst in hypersensitive disease resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4158–4163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang EWT, Bowler C, Hérouart D, Van Camp W, Villarroel R, Genetello C, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Differential regulation of superoxide dismutases in plants exposed to environmental stress. Plant Cell. 1991;3:783–792. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.8.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bogelen RA, Kelley PM, Neidhardt FC. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidative stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:26–32. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.26-32.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Straeten D, Chaerle L, Sharkov G, Lambers H, Van Montagu M. Salicylic acid enhances the activity of the alternative pathway of respiration in tobacco leaves and induces thermogenicity. Planta. 1995;196:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Vierling E. The roles of heat shock proteins in plants. Annu Rev Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:579–620. [Google Scholar]

- Warm E, Laties GG. Quantification of hydrogen peroxide in plant extracts by the chemiluminescence reaction with luminol. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:827–831. [Google Scholar]

- Willekens H, Inzé D, Van Montagu M, Van Camp W. Catalases in plants. Molecular Breeding. 1995;1:207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Yalpani N, Enyedi AJ, León J, Raskin I. Ultraviolet light and ozone stimulate accumulation of salicylic acid, pathogenesis-related proteins and virus resistance in tobacco. Planta. 1994;193:372–376. [Google Scholar]