Fast time-resolved phase-sensitive dual inversion-recovery imaging of the coronary arterial wall improves the success rate of obtaining good- to excellentquality images and of imaging sections orthogonal to the longitudinal axis of the vessel, with arterial wall thickness measurements showing a more distinct difference between healthy subjects and those with coronary artery disease risk factors.

Abstract

Purpose:

To develop a technique for time-resolved acquisition of phase-sensitive dual-inversion recovery (TRAPD) coronary vessel wall magnetic resonance (MR) images, to investigate the success rate in coronary wall imaging compared with that of single-frame imaging, and to assess vessel wall thickness in healthy subjects and subjects with risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD).

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-eight subjects (12 healthy subjects, 26 subjects with at least one CAD risk factor) provided informed consent for participation in this institutional review board–approved and HIPAA-compliant study. The TRAPD coronary vessel wall imaging sequence was developed and validated with a flow phantom. Time-resolved coronary artery wall images at three to five cine phases were obtained in all subjects. Qualitative and quantitative comparisons were made between TRAPD and conventional single-image wall measurements. Measurement reproducibility also was assessed. Statistical analysis was performed for all comparisons.

Results:

The TRAPD sequence successfully restored the negative polarity of lumen signal and enhanced lumen wall contrast on the cine images of the flow phantom and in all subjects. Use of three to five frames increased the success rate of acquiring at least one image of good to excellent quality from 76% in single-image acquisitions to 95% with the TRAPD sequence. The difference in vessel wall thickness between healthy subjects and subjects with CAD risk factors was significant (P < .05) with the TRAPD sequence (1.07 vs 1.46 mm, respectively; 36% increase) compared with single-frame dual inversion-recovery imaging (1.24 vs 1.55 mm, respectively; 25% increase). Intraobserver, interobserver, and interexamination agreement for wall thickness measurement were 0.98, 0.97, and 0.92, respectively.

Conclusion:

TRAPD imaging of coronary arteries improved arterial wall visualization and quantitative assessment by increasing the success rate of obtaining good- to excellent-quality images and sections orthogonal to the longitudinal axis of the vessel. This also resulted in vessel wall thickness measurements that show a more distinct difference between healthy subjects and those with CAD risk factors.

© RSNA, 2012

Supplemental material: http://radiology.rsna.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1148/radiol.12120068/-/DC1

Introduction

Coronary artery wall assessment with MR imaging has great potential as a radiation-free method in the assessment of coronary artery disease (CAD) and in the evaluation of coronary artery wall remodeling that precedes lumen narrowing (1–3). The procedure may thereby provide further insight into atherosclerosis and its response to various therapies (1–6). However, technical challenges still hinder coronary wall imaging in the clinical investigation of atherosclerosis and routine clinical use. These challenges include image degradation due to aperiodic intrinsic cardiac and chest wall motion. Residual motion due to uncompensated heart rate variability, motion within the navigator gating window, or other bulk motion often cause image blur and reduced sharpness (7–9). These challenges are further complicated by the time-dependent angular orientation of the small-caliber coronary artery wall, whereby mispositioning of the imaged section may cause the lumen-wall interface to disappear altogether (10–12). This can reduce coronary wall imaging reliability and success rate. While the failure rate of coronary magnetic resonance (MR) angiography ranges from 10% to 20% of the imaged cases (7), this rate is more pronounced at MR coronary wall imaging, where it ranges from 26% to 33% (3,6,11).

Two- and three-dimensional coronary artery wall imaging techniques have been proposed. Although three-dimensional imaging provides larger volumetric coverage, it requires sophisticated planning for successful blood nulling and prohibitively prolonged imaging times to achieve the necessary high spatial resolution with a greater risk of degraded image quality (13). Thus, the convenience of two-dimensional coronary vessel wall imaging and its relatively faster imaging time compared with three-dimensional imaging has led to its widespread use in clinical studies (2,6,14).

In planning two-dimensional coronary artery wall imaging, the section to be imaged is prescribed orthogonal to the longitudinal view of the artery at the location of interest. Inability to achieve true orthogonality is often encountered and dramatically alters the perceived wall and lumen dimensions. It may also cause failure to resolve the wall altogether (10,12). This orthogonality is crucial for obtaining an accurate measurement of wall thickness. However, acquiring images at only the blood signal nulling time makes it difficult to maintain section-vessel orthogonality, as this condition is highly sensitive to any cardiac rhythm variation or unaccounted for bulk displacement. Previously proposed solutions—including vessel tracking (15–19), subject-specific acquisition windows (20), and adaptive trigger delays (21–23)—cannot guarantee preservation of the orthogonality required for optimal two-dimensional wall imaging and accurate quantitative assessment.

Another challenge facing successful vessel wall imaging is the inherent requirement of blood signal nulling. A phase-sensitive dual inversion-recovery (PS-DIR) black-blood imaging technique (24) recently has been developed to address this challenge. PS-DIR relaxes the constraints related to blood signal nulling time and the period of minimal myocardial motion and thus enables black-blood imaging to be less sensitive to imaging time parameters. Thus, in theory, multiple coronary wall PS-DIR images can be acquired sequentially. This approach is therefore more likely to capture the required orthogonal view in one of the sequential time-resolved images than during only a single image acquisition, as the existing imaging techniques attempt to do. Thus, we introduce a time-resolved PS-DIR coronary vessel wall MR imaging technique that overcomes the loss of section-vessel orthogonality due to uncompensated residual motion.

The purpose of this study was to (a) develop a technique for time-resolved acquisition of PS-DIR (TRAPD) coronary vessel wall MR imaging, (b) investigate the success rate in coronary wall imaging compared with that of single-frame imaging, and (c) assess vessel wall thickness in healthy subjects and subjects with CAD risk factors.

Materials and Methods

TRAPD Technique

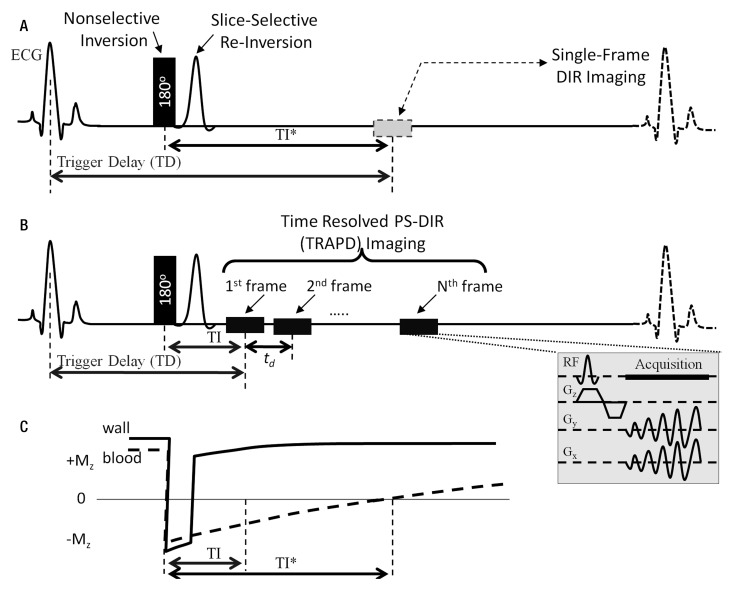

A single-frame dual inversion-recovery preparation pulse (Fig 1, A) consists of nonselective inversion directly followed by section-selective reinversion of magnetization at the anatomic level of interest followed by imaging when the blood signal is nulled. As previously described with PS-DIR (24), use of the sign of blood signal (Fig 1, C) into reconstruction permits lumen definition at an earlier acquisition time. Details on PS-DIR lumen signal restoration can be found in Appendix E1 (online). The PS-DIR sequence is modified in this work to acquire several successive cine phases or frames, as shown in Figure 1, B. In this TRAPD approach, each cine frame is then reconstructed into a PS-DIR sign-preserved magnitude image (24).

Figure 1:

Black-blood pulse sequence diagrams for, A, conventional dual inversion-recovery and, B, TRAPD imaging. One dual inversion-recovery image is acquired at the nominal blood-nulling inversion time (TI*) when blood magnetization is nulled. With TRAPD imaging, time-resolved cine phases or frames are acquired starting at an inversion time (TI) less than the blood-nulling inversion time. C, Diagram shows magnetization (Mz) of the vessel wall and blood and the magnitude and sign evolution as a function of time. Spiral acquisition module (bottom right) shows radiofrequency (RF) pulse and magnetization gradients (Gz, Gy, and Gx in section-selection, phase-encoding, and readout directions, respectively).

Neither the PS-DIR sequence nor the TRAPD sequence is commercially available, and both sequences require programming at the operating system level. Thus, the TRAPD sequence was developed and implemented with a commercial human 3-T system (Achieva; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands). For phantom experiments, please see Appendix E2 (online).

In Vivo Experiment and Measurements

Twenty-six subjects with at least one Framingham CAD risk factor (mean age, 48 years ± 13 [standard deviation]; 13 men [mean age, 50 years ± 16; age range, 20–69 years], 13 women [mean age, 48 years ± 20; age range, 18–75 years]) and 12 body mass index–matched healthy subjects without a history of or risk factors for CAD (<1% Framingham score) (mean age, 26 years ± 4; three men [age range, 24–29 years], nine women [mean age, 27 years ± 4; age range, 23–32 years]) participated in the study over a period of 24 months. Nine patients had hypertension, four were smokers, 14 had low high-density lipoprotein (or HDL) levels, and two had high hemoglobin A1C levels. All subjects provided written informed consent for participation in this study, which was approved by the institutional review board and was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Differences in age between healthy subjects and those with CAD risk factors and between male and female patients were analyzed by using the unpaired Student t test.

Scout images and coronary MR angiographic images of the right coronary artery were obtained similar to previously described methods (25,26).

For coronary vessel wall imaging, a single-section TRAPD data set was acquired with segmented k-space spiral acquisition with spectral-spatial water-selective excitation (27) and use of a 32-channel phased-array cardiac receiver coil and vector electrocardiographic triggering (28). Data from the 16 anterior surface coils were used for image reconstruction. Four or five cine frames were acquired in each cine data set depending on heart rate and the starting point of the rest period by using a fixed inversion time of 200 msec for the first image and a temporal resolution of 25 msec between subsequent frames. The spiral readout consisted of 20 interleaves per frame with a flat flip angle of 45°, an acquisition window of 20 msec, a repetition time of one RR interval, an echo time of 2.1 msec, and a spatial resolution of 0.69 × 0.69 × 8.0 mm (field of view, 200 × 200 × 8; matrix, 288 × 288). The reinversion section thickness of 15 mm was used to accommodate potential spatial misregistration between the magnetization-prepared slab and the imaged section due to through-plane cardiac motion. Data were acquired by using prospective navigator gating and correction (29). The navigator was localized at the lung-liver interface of the right hemidiaphragm with a 3-mm gating window and a correction factor of 0.6 in the superior-inferior direction (30). Immediately after dual inversion, a navigator-restore pulse (31) was used to optimize navigator performance. Phase-sensitive signed-magnitude images were reconstructed (24) and used in all later analyses.

All cine images were randomized, anonymized, and evaluated for image quality. Two observers (K.Z.A., A.M.G., 5 and 10 years experience in coronary artery imaging, respectively) scored the visual quality of the vessel wall by consensus reading. A score from 0 to 5 obtained by using previously described criteria (32) was assigned to each image. A score of 0 indicated the image was not acquired due to a short cardiac cycle; a score of 1, an undistinguishable coronary wall (very poor quality); a score of 2, the coronary artery wall was partly visible (<50%) with incomplete borders (poor quality); a score of 3, 50%–75% of the coronary artery wall was visible and distinguishable from the lumen and surroundings (fair quality); a score of 4, the coronary artery wall was mostly distinguishable with only small portions of the vessels (<25%) not present (good quality); and a score of 5, the coronary artery wall was completely visible with sharply defined borders (excellent quality). An image with good or excellent quality was considered adequate for quantitative analysis. These images were all pooled and analyzed, with the observers blinded to subject information.

A semiautomatic algorithm for wall thickness measurement that was based on the work of Botnar et al (33) was developed and used to measure wall thickness. More details about the method used to measure wall thickness can be found in Appendix E3 (online).

Wall signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), lumen-wall contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), and vessel wall sharpness were calculated for all good- and excellent-quality TRAPD signed-magnitude images by using the following formulas: SNR = Mw/SDn and CNR = (Mw − Mb)/SDn, where mean signal intensity in the center of the lumen (Mb) was calculated, mean vessel wall signal (Mw) was calculated inside the vessel wall, and standard deviation of noise (SDn) was calculated inside the lung in a structure-free region. Vessel wall sharpness was measured with a method similar to that reported by Etienne et al (34). All measurements and calculations were performed by observer 1 (K.Z.A.).

Statistical Analysis

The differences in body mass index and age between healthy subjects and those with CAD risk factors and the difference in age between men and women with CAD risk factors were analyzed by using the unpaired Student t test. To evaluate the incremental effect of the additional TRAPD cine frames on vessel wall thickness measurement, five image subgroups containing progressive numbers of cine phases were created for each subject. The individual subgroups contained the first cine phase image (group 1), the first and second cine phase images (group 2), the first three cine phase images (group 3), the first four cine phase images (group 4), and all five cine phase images (group 5). These five subgroups were created for each population (those with and those without CAD risk factors). In each subgroup, the time frame with minimum vessel wall thickness was identified and considered the most accurate measurement of wall thickness among the cine phases that were acquired in that particular subgroup. This was based on the expectation that the lack of section-vessel orthogonality results in increased apparent wall thickness. In each subject population, Friedman repeated-measures analysis of variance and trend analysis tests were used to examine the equality of the thickness measurements obtained with single-frame images and the thinnest vessel wall measurement from each subgroup. The tests were also used to identify the number of frames with significant influence on minimum wall thickness measurement. Thus, the cumulative effect of multiple cine phases was assessed in comparison with single (first cine phase) vessel wall imaging that is equivalent to the typical dual inversion-recovery technique. The thinnest vessel wall measurement obtained in each of these cine phase subgroups for the subjects with CAD was compared with the thinnest vessel wall measurement obtained in the corresponding cine phase subgroup in subjects without CAD. A Mann-Whitney test was used for this latter comparison. Signal-to-noise ratio, contrast-to-noise ratio, and vessel wall sharpness measurements from the additional time frames were compared with those from the first frame by using the two-tailed paired Student t test.

For intra- and interobserver reproducibility, all image processing and wall thickness measurements were repeated by observers 1 and 2 for 20 randomly selected subjects. The first measurements performed by observer 1 (K.Z.A.) were considered the reference standard. Additionally, to assess interexamination reproducibility, additional sets of TRAPD images were acquired in 18 subjects during the same session and at the same coronary segments. These additional sets of TRAPD images were used only to assess reproducibility. Images underwent the same blind procedures used for the original data sets, including analysis and wall thickness measurements. Data from the different measurements and different examinations were compared by using the paired t test. Intraobserver, interobserver, and interexamination correlations were evaluated by using the Pearson correlation coefficient (R). The Bland-Altman method was used to study systematic mean differences and 95% limits of agreements. The intraclass correlation coefficient for absolute agreement was calculated to assess intraobserver, interobserver, and interexamination agreement. The coefficient of variance was also determined. The coefficient of variance was defined as the standard deviation of the differences between the two measurements divided by the mean of both measurements.

MedCalc version 11.6 software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used for all statistical analyses. A Bonferroni-corrected P value of less than .05 was considered indicative of a significant difference.

Results

Phantom results are presented in Appendix E2, as well as in Figures E1 and E2 (online).

All 38 subjects underwent successful imaging. No statistical difference (P = .06) was found between the body mass index of subjects with CAD risk factors (mean, 25 ± 5; range, 16–34) and healthy subjects (mean, 22 ± 4; range, 20–30). Subjects with CAD risk factors were significantly older than healthy subjects (P < .001), while there was no significant difference in age between men and women with CAD risk factors (P = .7).

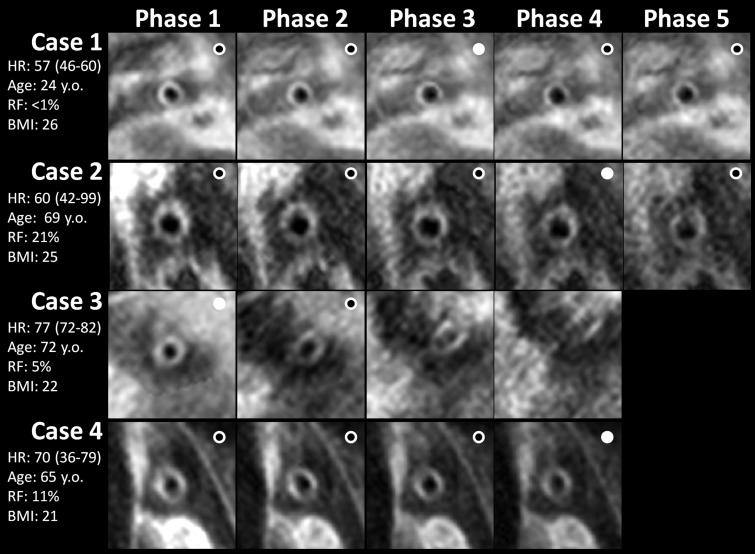

All data sets except two had at least one time frame image with good or higher-quality scores. Examples of TRAPD data sets from subjects with and those without CAD are shown in Figure 2. The distribution of image scores over the individual cine frames is summarized in Figure E3 (online). In all subjects, the interval from trigger delay to the next R wave was long enough to acquire at least three TRAPD images. This interval was long enough to acquire four and five frames in 37 (97%) and 28 (73%) of the 38 subjects, respectively. The first image frame had adequate quality in only 29 (76%) of the 38 subjects. The cumulative success rate of acquiring at least one adequate-quality image increased from 76% in single-image acquisitions to 95% (36 of 38 subjects) when four or five frames were acquired. The thinnest wall measurements were mostly obtained from frames 1, 2, and 3 in eight (21%), 10 (26%), and 11 (29%) of the 38 subjects, respectively. The fourth and fifth frames contributed smaller percentages (16% [six of 38 subjects] and 8% [three of 38 subjects], respectively).

Figure 2:

TRAPD signed-magnitude cine phases of four different subjects show subject variability encountered in the study. White circles = images with good- or excellent-quality scores, filled circles = images with thinnest vessel walls. Cases 1 and 2 are a healthy subject in whom all images had adequate (good or excellent) scores for quantitative analysis. Cases 3 and 4 subjects with CAD risk factors and short cardiac cycles in whom it was impossible to acquire the fifth frames. Case 3 also shows a situation in which only the first two frames had acceptable quality. The label beside each case shows average, minimum, and maximum heart rate (HR) in beats per minute during the examination, age in years, Framingham risk factor (RF), and body mass index (BMI).

Mean and standard deviation of the minimum vessel wall thickness in each subgroup of time frames are shown in Figure E4 (online) and show thinner wall measurements in both healthy subjects and those with CAD risk factors when five frames are used (1.07 and 1.46 mm, respectively) compared with measurements obtained with a single frame (1.24 and 1.55 mm, respectively). In addition, a larger difference in wall thickness between healthy subjects and those with CAD was obtained (0.38 mm difference) when three or more frames were used to identify the wall thickness, compared with single-frame calculations (0.31-mm difference). This corresponds to a 36% increase in patients’ wall thickness compared with that with single-frame dual inversion-recovery imaging (25% increase). Finally, more wall thickness precision was demonstrated by narrower standard deviations by using five frames (healthy subjects, 0.16 mm; subjects with CAD risk factors, 0.22 mm) than by using a single frame (healthy subjects, 0.20 mm; subjects with CAD risk factors, 0.26 mm).

Friedman repeated-measures analysis of variance results showed that in healthy subjects and subjects with CAD risk factors separately, vessel wall thickness continued to decrease significantly (P < .05) when two or three images were used in calculations in comparison with single-frame measurements. There was no further reduction in wall thickness when including the additional fourth and fifth frames (P > .05). The thinner wall measurements both in healthy subjects and in subjects with CAD risk factors were significant, as indicated by the trend analysis (decline trend, P < .0001). Mann-Whitney tests showed significant differences between healthy subjects and those with CAD risk factors (P < .001), with a smaller P value associated with the use of more time frames.

Image signal-to-noise ratio, contrast-to-noise ratio, and vessel wall sharpness measures are summarized in Table E1 (online). When compared with the first frame, there was a trend toward decline in both signal-to-noise ratio and contrast-to-noise ratio of the later frames (P < .05). This decline was not significant until the fourth and fifth frames (P < .05). Edge sharpness loss was not significant in any frames compared with the first frame.

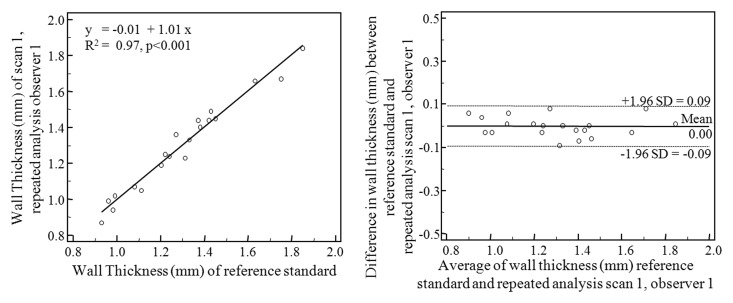

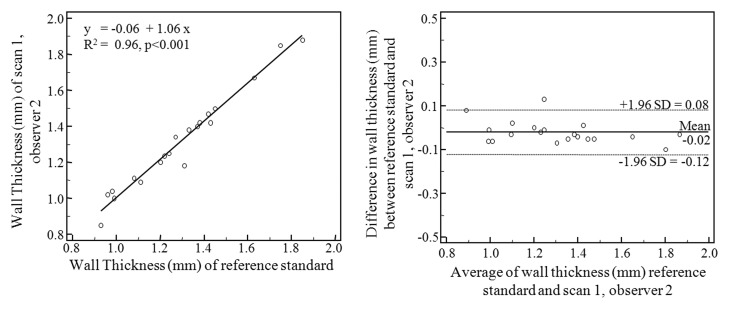

The repeated wall thickness measurements obtained by the first observer (K.Z.A.) showed no significant difference when compared with the first measurements (reference standard) (1.30 mm ± 0.26 vs 1.29 mm ± 0.25, P = .89). Measurements obtained from the first and second examinations performed by the first observer were similar as well (1.36 mm ± 0.28 vs 1.35 mm ± 0.26, P = .98). Measurements obtained by the second observer showed no significant difference (1.32 mm ± 0.27 vs 1.29 mm ± 0.25, P = .09).

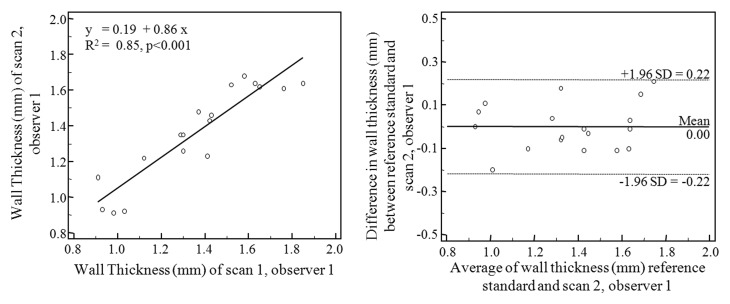

Scatterplots and Bland-Altman plots are shown in Figure 3. The highest correlations were associated with repeated measurements of the same data by the same observer (R2 = 0.97, P < .001) and by different observers (R2 = 0.96, P < .001). The degree of interexamination measurement correlation was lower (R2 = 0.85, P < .001). Bland-Altman analysis shows intraobserver mean difference of −0.002 mm (95% limits of agreement: −0.095, 0.092), interobserver mean difference of −0.021 mm (95% limits of agreements: −0.123, 0.082), and interexamination mean difference of 0.001 mm (95% limits of agreement: −0.217, 0.218). The intraclass correlation coefficient for wall thickness measurement of intraobserver, interobserver, and interexamination agreement was 0.98, 0.97, and 0.92, respectively. The coefficient of variance was 2.53% for intraobserver analysis, 2.96% for interobserver analysis, and 5.62% for interexamination analysis.

Figure 3a:

Scatterplots (left) and Bland-Altman plots (right) of wall thickness measurements performed by observer 1 with data from examination 1 (reference standard) compared with (a) repeated measurements by observer 1 with data from examination 1, (b) measurements performed by observer 2 with data from examination 1, and (c) measurements performed by observer 1 with data from examination 2.

Figure 3b:

Scatterplots (left) and Bland-Altman plots (right) of wall thickness measurements performed by observer 1 with data from examination 1 (reference standard) compared with (a) repeated measurements by observer 1 with data from examination 1, (b) measurements performed by observer 2 with data from examination 1, and (c) measurements performed by observer 1 with data from examination 2.

Figure 3c:

Scatterplots (left) and Bland-Altman plots (right) of wall thickness measurements performed by observer 1 with data from examination 1 (reference standard) compared with (a) repeated measurements by observer 1 with data from examination 1, (b) measurements performed by observer 2 with data from examination 1, and (c) measurements performed by observer 1 with data from examination 2.

Discussion

This study shows that acquisition of multiple consecutive coronary vessel wall images is feasible with TRAPD imaging and reconstruction. This method has resulted in an improved success rate (95%) in obtaining good- to excellent-quality vessel wall images compared with the traditional single-image dual inversion-recovery technique (76%). Additionally, the difference between vessel wall thickness in subjects without and those with CAD risk factors is significantly larger (1.07 vs 1.46 mm, 36% increase) with the TRAPD technique than with the single-cardiac-phase imaging technique (1.24 vs 1.55 mm, 25% increase). In an earlier study (34), wall thickness measurements from single-frame PS-DIR images with a subject-independent inversion time as short as 150 msec were shown to correlate well with conventional dual inversion-recovery images at subject-specific blood-nulling inversion time, without a significant difference. On the basis of the results of that study, comparison of TRAPD multiframe measurements with those of PS-DIR at an inversion time of 200 msec would not be expected to be significantly different from wall measurements obtained with dual inversion-recovery images at subject-specific blood-nulling inversion time. It is important to note that phase-sensitive reconstruction alleviated the need to acquire data during only the subject-specific nulling time. Here, the relaxation of that constraint was a key factor in successful coronary wall time-resolved imaging. All data in this study were acquired by using a subject-invariant inversion time. A steady-flow phantom was used to simulate flow in the coronary artery during the diastolic rest period, as intended in subject imaging. Phantom results show that the TRAPD sequence successfully restored lumen-wall contrast at several time frames, which is limited to a single frame in typical vessel wall imaging techniques. Thus, TRAPD imaging yields successful blood pool nulling without the need for meticulous planning and matched adjustments of inversion time and trigger delay. The relatively low success rate of 76% in the use of a single frame is probably due to R-R variability resulting in small changes in trigger delay and vessel orthogonality. Use of a flat 45° flip angle, reduced navigator efficiency, and cardiac motion artifacts are potential causes for reduction of signal-to-noise ratio and image quality in later TRAPD cine frames. Ramped flip angle excitation might improve signal-to-noise ratio of the later frames; however, these frames will likely reside outside the rest period and therefore will be affected by more motion artifacts than the early frames. The percentage of cases with adequate-quality images increased from 76% with the traditional single-frame method to 95% with five consecutive frames. The extra frames provided an additional opportunity to compensate successfully for single-frame section timing or mispositioning due to residual or unpredicted cardiac and chest wall motion. All these factors combined to improve the ability to capture the trigger delay rest period and reduce imaging failure. This may explain the improved delineation of the vessel wall and the larger resolved arterial wall thickening (from 25% to 36%) in subjects with CAD risk factors relative to healthy subjects. The results also show excellent intraobserver, interobserver, and interexamination reproducibility and agreement demonstrated by the Bland-Altman and correlation measures.

Our study was not without limitations. One limitation was that the TRAPD sequence has a limited two-dimensional coverage per pass. However, this enables short acquisition time, which permits TRAPD data to be acquired at multiple sites.

Another potential limitation of the proposed technique is the 8-mm section thickness, which might lead to volume-averaging artifacts. This was the minimum thickness possible in our protocol when using spectral spatial water-selective excitation that is necessary to preserve short temporal resolution, thereby avoiding fat-suppression prepulses, and to maintain adequate contrast-to-noise ratio.

Interexamination reproducibility was tested for vessel wall imaging only and not for the entire coronary MR angiographic examination. Since these initial steps that include preexamination preparation already have been published numerous times and the coronary MR angiographic image was used to plan the vessel wall imaging, we opted to replan and reexamine only the vessel wall imaging technique, without repeating the preexamination steps. However, in each interexamination reproducibility acquisition, the TRAPD vessel wall technique was replanned, not merely reexamined, at a similar location of the coronary segment. The healthy subjects were significantly younger than the subjects with CAD risk factors. This was difficult to control for, since most patients with CAD are usually older. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, this is the first study to show the difference between subjects with CAD risk factors and healthy subjects by using this technique with a 95% success rate.

In conclusion, TRAPD imaging of the coronary artery wall improves the success rate of obtaining good- to excellent-quality images and imaging sections orthogonal to the longitudinal axis of the vessel, with artery wall thickness measurements showing a more distinct difference between normal and patient populations.

Advances in Knowledge.

• High-spatial-resolution time-resolved imaging of the coronary artery wall is feasible at 3 T with multiframe dual inversion-recovery imaging by using spiral k-space acquisition and phase-sensitive reconstruction.

• Coronary vessel section orthogonality, which is critical for accurate wall thickness measurement, is better achieved with time-resolved imaging than with a single-time-frame approach because of cardiac cycle phase dependence.

• Preliminary experience with the time-resolved phase-sensitive dual inversion-recovery (TRAPD) sequence in healthy subjects and subjects with risk factors for coronary artery disease suggests improved ability to distinguish coronary wall thickness between the two groups (1.07 vs 1.46 mm, respectively; 36% increase) compared with that with single-frame dual inversion-recovery imaging (1.24 vs 1.55 mm, respectively; 25% increase).

Implications for Patient Care.

• This time-resolved multiframe technique improves the success rate of obtaining vessel wall images with good to excellent image quality compared with the success rate of conventional single-frame imaging.

• Overcoming residual uncompensated cardiac motion in coronary artery wall imaging is feasible without subject-dependent optimization or section tracking.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: K.Z.A. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. A.M.G. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. R.I.P. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Received January 9, 2012; revision requested March 8; revision received April 27; accepted May 21; final version accepted May 29.

Funding: The authors are employees of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- CAD

- coronary artery disease

- PS-DIR

- phase-sensitive dual inversion-recovery

- TRAPD

- time-resolved acquisition of PS-DIR

References

- 1.Botnar RM, Stuber M, Kissinger KV, Kim WY, Spuentrup E, Manning WJ. Noninvasive coronary vessel wall and plaque imaging with magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2000;102(21):2582–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fayad ZA, Fuster V, Fallon JT, et al. Noninvasive in vivo human coronary artery lumen and wall imaging using black-blood magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2000;102(5):506–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miao C, Chen S, Macedo R, et al. Positive remodeling of the coronary arteries detected by magnetic resonance imaging in an asymptomatic population: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53(18):1708–1715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med 1987;316(22):1371–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim WY, Astrup AS, Stuber M, et al. Subclinical coronary and aortic atherosclerosis detected by magnetic resonance imaging in type 1 diabetes with and without diabetic nephropathy. Circulation 2007;115(2):228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terashima M, Nguyen PK, Rubin GD, et al. Right coronary wall CMR in the older asymptomatic advance cohort: positive remodeling and associations with type 2 diabetes and coronary calcium. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010;12:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangcharoen T, Jahnke C, Koehler U, et al. Impact of heart rate variability in patients with normal sinus rhythm on image quality in coronary magnetic angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;28(1):74–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahnke C, Nehrke K, Paetsch I, et al. Improved bulk myocardial motion suppression for navigator-gated coronary magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007;26(3):780–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horiguchi J, Fukuda H, Yamamoto H, et al. The impact of motion artifacts on the reproducibility of repeated coronary artery calcium measurements. Eur Radiol 2007;17(1):81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schär M, Kim WY, Stuber M, Boesiger P, Manning WJ, Botnar RM. The impact of spatial resolution and respiratory motion on MR imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. J Magn Reson Imaging 2003;17(5):538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim WY, Stuber M, Kissinger KV, Andersen NT, Manning WJ, Botnar RM. Impact of bulk cardiac motion on right coronary MR angiography and vessel wall imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001;14(4):383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antiga L, Wasserman BA, Steinman DA. On the overestimation of early wall thickening at the carotid bulb by black blood MRI, with implications for coronary and vulnerable plaque imaging. Magn Reson Med 2008;60(5):1020–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott AD, Keegan J, Firmin DN. Motion in cardiovascular MR imaging. Radiology 2009;250(2):331–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macedo R, Chen S, Lai S, et al. MRI detects increased coronary wall thickness in asymptomatic individuals: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;28(5):1108–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foo TK, Ho VB, Hood MN. Vessel tracking: prospective adjustment of section-selective MR angiographic locations for improved coronary artery visualization over the cardiac cycle. Radiology 2000;214(1):283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatehouse PD, Keegan J, Yang GZ, Mohiaddin RH, Firmin DN. Tracking local volume 3D-echo-planar coronary artery imaging. Magn Reson Med 2001;46(5):1031–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saranathan M, Ho VB, Hood MN, Foo TK, Hardy CJ. Adaptive vessel tracking: automated computation of vessel trajectories for improved efficiency in 2D coronary MR angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001;14(4):368–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewan M, Hager GD, Lorenz CH. Image-based coronary tracking and beat-to-beat motion compensation: feasibility for improving coronary MR angiography. Magn Reson Med 2008;60(3):604–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott AD, Keegan J, Firmin DN. High-resolution 3D coronary vessel wall imaging with near 100% respiratory efficiency using epicardial fat tracking: reproducibility and comparison with standard methods. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;33(1):77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plein S, Jones TR, Ridgway JP, Sivananthan MU. Three-dimensional coronary MR angiography performed with subject-specific cardiac acquisition windows and motion-adapted respiratory gating. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180(2):505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann MHK, Lessick J, Manzke R, et al. Automatic determination of minimal cardiac motion phases for computed tomography imaging: initial experience. Eur Radiol 2006;16(2):365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ustun A, Desai M, Abd-Elmoniem KZ, Schar M, Stuber M. Automated identification of minimal myocardial motion for improved image quality on MR angiography at 3 T. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188(3):W283–W290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roes SD, Korosoglou G, Schär M, et al. Correction for heart rate variability during 3D whole heart MR coronary angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;27(5):1046–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abd-Elmoniem KZ, Weiss RG, Stuber M. Phase-sensitive black-blood coronary vessel wall imaging. Magn Reson Med 2010;63(4):1021–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gharib AM, Ho VB, Rosing DR, et al. Coronary artery anomalies and variants: technical feasibility of assessment with coronary MR angiography at 3 T. Radiology 2008;247(1):220–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuber M, Botnar RM, Danias PG, Kissinger KV, Manning WJ. Submillimeter three-dimensional coronary MR angiography with real-time navigator correction: comparison of navigator locations. Radiology 1999;212(2):579–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer CH, Pauly JM, Macovski A, Nishimura DG. Simultaneous spatial and spectral selective excitation. Magn Reson Med 1990;15(2):287–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer SE, Wickline SA, Lorenz CH. Novel real-time R-wave detection algorithm based on the vectorcardiogram for accurate gated magnetic resonance acquisitions. Magn Reson Med 1999;42(2):361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danias PG, McConnell MV, Khasgiwala VC, Chuang ML, Edelman RR, Manning WJ. Prospective navigator correction of image position for coronary MR angiography. Radiology 1997;203(3):733–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Ehman RL. Retrospective adaptive motion correction for navigator-gated 3D coronary MR angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2000;11(2):208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuber M, Botnar RM, Spuentrup E, Kissinger KV, Manning WJ. Three-dimensional high-resolution fast spin-echo coronary magnetic resonance angiography. Magn Reson Med 2001;45(2):206–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malayeri AA, Macedo R, Li D, et al. Coronary vessel wall evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: determinants of image quality. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2009;33(1):1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Botnar RM, Stuber M, Danias PG, Kissinger KV, Manning WJ. Improved coronary artery definition with T2-weighted, free-breathing, three-dimensional coronary MRA. Circulation 1999;99(24):3139–3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Etienne A, Botnar RM, Van Muiswinkel AM, Boesiger P, Manning WJ, Stuber M. “Soap-Bubble” visualization and quantitative analysis of 3D coronary magnetic resonance angiograms. Magn Reson Med 2002;48(4):658–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.