Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a neurodevelopmental autism spectrum disorder caused by mutations in the methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene. Here, we describe the first characterization and neuronal differentiation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells derived from Mecp2-deficient mice. Fully reprogrammed wild-type (WT) and heterozygous female iPS cells express endogenous pluripotency markers, reactivate the X-chromosome and differentiate into the three germ layers. We directed iPS cells to produce glutamatergic neurons, which generated action potentials and formed functional excitatory synapses. iPS cell-derived neurons from heterozygous Mecp2308 mice showed defects in the generation of evoked action potentials and glutamatergic synaptic transmission, as previously reported in brain slices. Further, we examined electrophysiology features not yet studied with the RTT iPS cell system and discovered that MeCP2-deficient neurons fired fewer action potentials, and displayed decreased action potential amplitude, diminished peak inward currents and higher input resistance relative to WT iPS-derived neurons. Deficiencies in action potential firing and inward currents suggest that disturbed Na+ channel function may contribute to the dysfunctional RTT neuronal network. These phenotypes were additionally confirmed in neurons derived from independent WT and hemizygous mutant iPS cell lines, indicating that these reproducible deficits are attributable to MeCP2 deficiency. Taken together, these results demonstrate that neuronally differentiated MeCP2-deficient iPS cells recapitulate deficits observed previously in primary neurons, and these identified phenotypes further illustrate the requirement of MeCP2 in neuronal development and/or in the maintenance of normal function. By validating the use of iPS cells to delineate mechanisms underlying RTT pathogenesis, we identify deficiencies that can be targeted for in vitro translational screens.

Keywords: Autism, disease modelling, induced pluripotent stem cells, neuron electrophysiology, Rett syndrome

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a severe neurodevelopmental autism spectrum disorder caused in the majority of cases by loss-of-function mutations in the methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene on the X-chromosome.1 Girls with RTT exhibit what appears to be normal development for the first 6–18 months, which then apparently stalls and is followed by neurocognitive regression and the onset of autistic-like behaviour.2 Although widely expressed, MeCP2 is most abundant in mature neurons, and its expression pattern correlates with neuronal differentiation and maturation.3

The lack of proper MeCP2 function results in a predominantly neurological phenotype in both humans and mice,1 and MeCP2 dysfunction in mature post-mitotic neurons alone is sufficient to cause phenotypic impairments in mice.4 The effects of MeCP2 dysfunction on neuronal morphology, intrinsic membrane properties and synaptic connectivity vary across different brain regions and synaptic types.5 Nevertheless, the prevailing view is that subtle deficits in synaptogenesis and/or synaptic function underlie the profound alterations in brain network activity in RTT. Interestingly, mutations in MECP2 have been implicated in a number of neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 As a consequence, studies delineating phenotypes associated with Mecp2 deficiency may shed light on the pathogenesis of multiple neurological syndromes.

While neurophysiological assessments in MeCP2-deficient tissue have given insights into Rett pathogenesis, these investigations are hampered by the poor breeding fecundity and thus limited availability of MeCP2-deficient mice.12 An attractive alternative to breeding MeCP2-deficient mice is the use of neuronally differentiated induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells13, 14 as a model system. Recent studies have now shown that pluripotent stem cells can be generated directly from RTT patient fibroblasts,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and that these cells can be differentiated into neurons in vitro. While constituting a major advancement to allow patient-based in vitro assessments, similar attempts to generate iPS cells from mouse models of RTT have not been conducted to date. Here, using the Mecp2308 mouse as a model system,22 we discover dysfunctional phenotypes relevant to RTT through a detailed characterization of more than a dozen electrophysiological properties assessed in large numbers of neurons generated in vitro from iPS cells.

Materials and methods

For more detailed information, please refer to Supplementary Methods.

Embryoid body (EB)-mediated differentiation

Mouse iPS cell colonies were dissociated by treatment with 0.25% trypsin–ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid and cultured in suspension in non-treated petri dishes for 8 days. Cells were cultured in EB media containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS, 4-mM L-glutamine, 4-mM penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine, 0.1-mM MEM non-essential amino acids and 0.55-mM 2-mercaptoethanol (all Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) without leukemia inhibitory factor. EBs were then plated onto gelatin-coated tissue culture grade dishes for an additional 8 days for further differentiation before immunocytochemistry for markers representing the three germ layers. Media were changed every other day throughout the 16-day differentiation.

Teratoma formation assays

Teratoma experiments with NOD/SCID immunodeficient mice were performed as previously described.15, 16 All procedures using animals have been approved by the SickKids Animal Care Committee under the auspices of The Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Neuronal differentiation

Neuronal differentiation of iPS cell lines was performed using methods adapted with modifications from the retinoic acid-mediated differentiation protocol published by Bibel et al.23, 24 for generating glutamatergic neurons. Timing of subsequent media changes were as specified by Bibel et al.23, 24 for long-term culture of differentiated neurons.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made at room temperature 13–20 days after dissociated neuronal precursors were plated onto poly-L-ornithine/laminin dishes. Electrical signals were digitized with a DigiData 1200 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and filtered at 2 kHz. Data were recorded using an Axopatch 1-D amplifier (Molecular Devices) and analyzed offline using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices).

Results

Establishment and characterization of wild-type and Mecp2308 mouse iPS cells

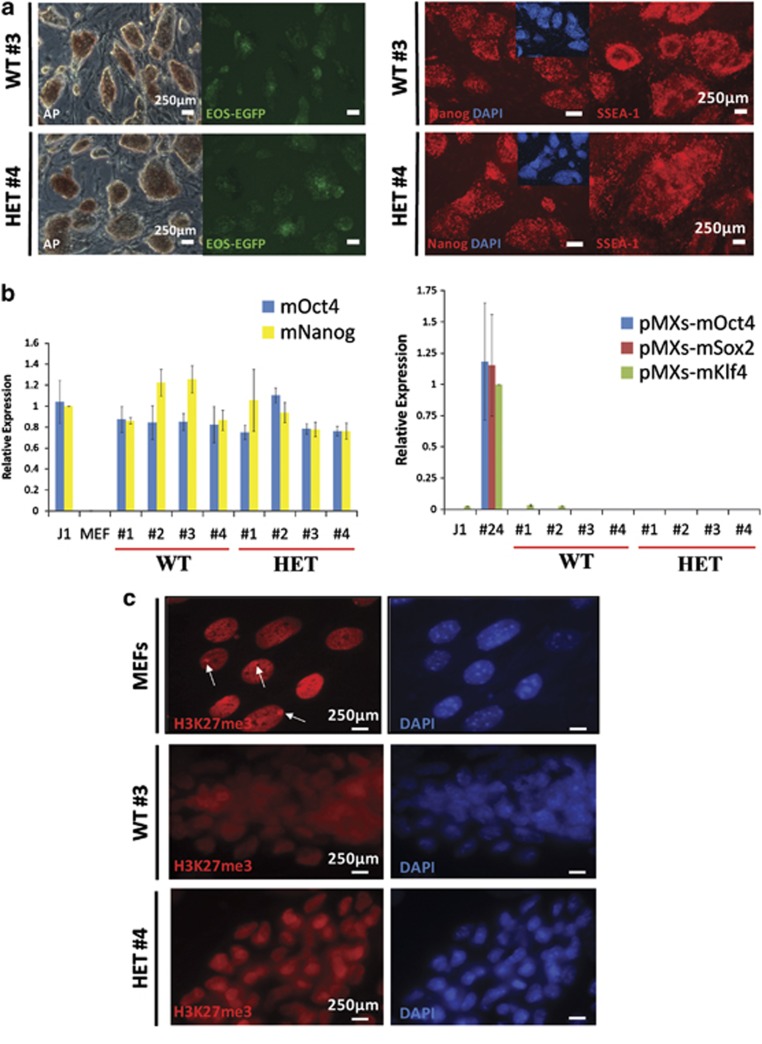

We first established iPS cell lines from female Mecp2 wild-type and Mecp2308 heterozygous fibroblasts (referred to as WT and HET, respectively). Skin samples were isolated from a litter of embryonic mice, and fibroblasts were expanded and genotyped by PCR to confirm presence or absence of the truncated Mecp2308 allele. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were infected with retroviruses expressing Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (excluding c-Myc) and EOS reporter lentivirus to mark pluripotency as previously described.15, 16 EOS-EGFP-positive colonies with mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell-like morphology were expanded under puromycin selection, and the pluripotency of four WT and four HET iPS cell lines was extensively characterized, with representative data for WT #3 and HET #4 shown in Figures 1 and 2, and data for HET #1 previously published.15, 16 Immunocytochemistry verified the lines stain positive for alkaline phosphatase and express pluripotency markers Nanog and SSEA-1 (Figure 1a and Supplementary Figure 1a). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) revealed the lines reactivate endogenous pluripotency loci, and primers specific to the retroviral transgenes demonstrated that the lines silence the exogenous transgenes, indicating full reprogramming (Figure 1b). Female mouse iPS cells have been shown to reactivate the silent X-chromosome in somatic cells during reprogramming.25 Immunocytochemistry for the H3K27me3 silencing mark revealed that WT and HET lines reactivate the inactive X (Figure 1c and Supplementary Figure 1b). Immunofluorescence using an antibody to the C-terminus of MeCP2 that is unable to detect the truncated MeCP2308 protein revealed that the heterozygous iPS cell lines express WT MeCP2 in all cells, indicating active expression from both X-chromosomes following reprogramming (Supplementary Figure 1c and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The genotypes of the cell lines were confirmed by PCR (Supplementary Figure 2a). We also confirmed that the WT lines were female, to provide the most appropriate control for the female HET lines (Supplementary Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

WT and Mecp2308 iPS cells are pluripotent. (a) WT #3 and HET #4 iPS cell lines express pluripotency markers alkaline phosphatase, Nanog and SSEA-1 by immunocytochemistry. (b) qRT-PCR analysis demonstrates that WT and HET iPS cell lines reactivate endogenous pluripotency loci (mouse mOct4 and mNanog) similar to the J1 ES cell line and also silence exogenous viral reprogramming transgenes (pMXs). The published partially reprogrammed EOS3F-24 (#24) iPS cell line is a positive control for transgene expression. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts are a differentiated cell type-negative control for pluripotency marker expression.15 (c) DAPI-colocalized H3K27me3 foci representing the inactive X-chromosome are absent in WT #3 and HET #4 iPS cells, in comparison with mouse embryonic fibroblasts (arrows). The H3K27me3 silencing mark is not present in all mouse embryonic fibroblasts because they are a mixture of male and female cells. Scale bars: 250 μm.

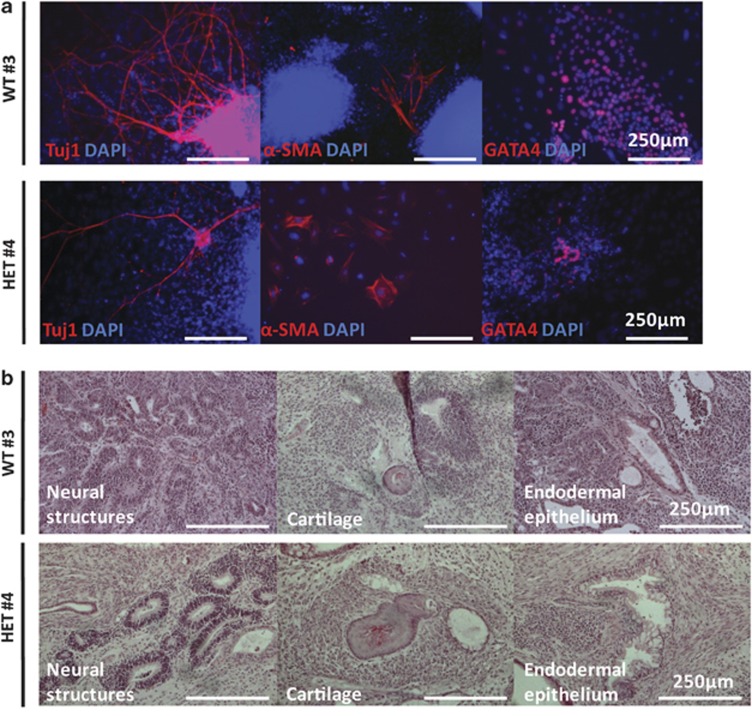

Figure 2.

iPS cell lines are functionally pluripotent in vitro and in vivo. (a) WT #3 and HET #4 generate cells corresponding to the three germ layers (ectoderm, Tuj1/βIII-tubulin; mesoderm, α-SMA; and endoderm, GATA4) following EB-mediated in vitro differentiation. (b) WT #3 and HET #4 differentiate into the three germ layers (ectoderm, neural structures; mesoderm, cartilage; and endoderm, endodermal epithelium) in vivo in teratoma formation assays with immunodeficient mice. Scale bars: 250 μm.

Both WT and HET mouse iPS cell lines differentiate appropriately into the three embryonic germ layers in vitro and in vivo

To assess in vitro differentiation capacity, iPS cells were cultured in suspension to form cellular aggregates (EBs). These were transferred onto an adhesive substrate and subjected to immunocytochemical analyses demonstrating that the lines spontaneously differentiated into cell types corresponding to ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm in vitro (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure 3a). Further, upon injection into the testes of immunodeficient mice, these lines also formed teratomas that contained mature tissue types corresponding to these three embryonic germ layers in vivo (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure 3b). At this point, we performed Southern blots to confirm that the lines contain all three transgenes (Supplementary Figure 4). This analysis revealed that the iPS cells are subclones with the same integration sites derived from the same reprogramming event, a finding that presented the opportunity to evaluate whether phenotypic differences accumulate in the different sublines during the time they have been cultured independently. Examination of the qRT-PCR data (Figure 1b) suggests subtle gene expression differences. To assess whether phenotypic variation accumulates between these sublines, we directed the iPS cells to differentiate into neurons for functional studies.

WT and HET iPS cells can be directed to differentiate into glutamatergic neurons in vitro

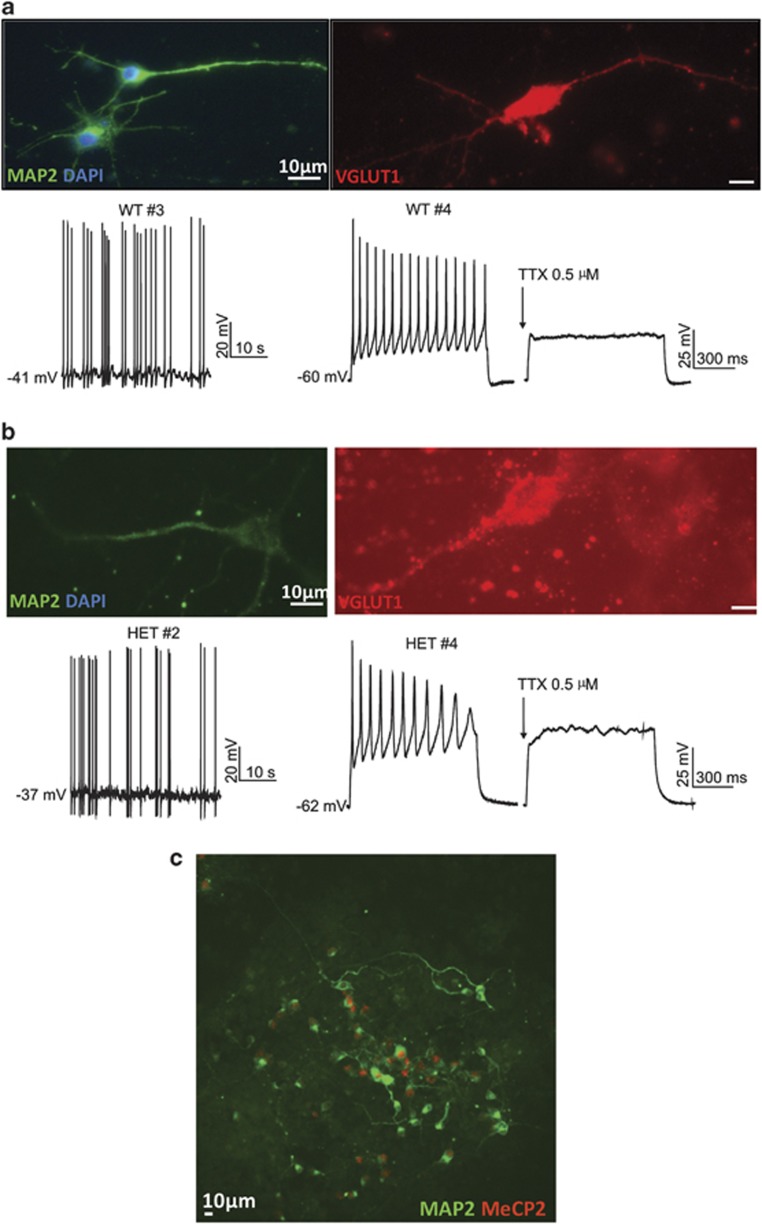

Progenitor cells isolated from MeCP2-deficient mouse brain retain the ability to properly differentiate into neurons in vitro.26 To test whether WT and HET mouse iPS cells also retain this function, we directed the iPS cells to differentiate into glutamatergic neurons using a protocol previously shown to be effective in mouse ES cells.23, 24 Retinoic acid treatment of EBs derived from both WT and HET iPS cell lines generated cells possessing neuronal-like morphologies that expressed neuronal markers microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) and vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1) (Figures 3a and b). Consistent with random X-chromosome inactivation during differentiation, neurons generated from HET cells contained a mosaic of cells expressing either the mutant or WT Mecp2 allele (as detected with a C-terminal antibody unable to detect the truncated protein) (Figure 3c, Supplementary Figure 5). MeCP2 staining was detected in 52% of cells (n=1388) following neuronal differentiation of the heterozygous lines, indicating that recapitulation of X-chromosome inactivation yielded equal proportions of mutant and WT neurons in the HET cultures. This protocol is highly efficient for generating glutamatergic neurons, and yields fewer than 5% GABAergic neurons.23, 24 In accordance, virtually all cells express VGLUT1, and only low levels of GABAergic marker glutamate decarboxylase 65/67 (GAD65/67), the γ-aminobutyric acid synthetic enzymes, are detected (Supplementary Figures 6a and b).

Figure 3.

iPS-derived cells display specific neuronal markers and generate TTX-sensitive action potentials, following differentiation directed to glutamatergic neurons. (a) WT iPS-derived cells express MAP2 and VGLUT1 as shown by immunocytochemistry (upper). A representative trace of a spontaneously discharging WT iPS-derived cell during current-clamp recording is shown in the lower left. Current-clamp recordings from a different WT iPS-derived cell are shown in the lower right pair of traces. In this otherwise silent cell, action potentials triggered by current injection (+110 pA) (left) were blocked by TTX (0.5 μM; right). (b) HET iPS-derived cells express MAP2 and VGLUT1 (upper). Representative traces during current-clamp recording show a spontaneously discharging HET iPS-derived cell (lower left) and another cell (lower right pair) in which action potentials, elicited by current injection (+110 pA), were blocked by TTX. (c) HET iPS-derived cultures show a mix of MeCP2+ and MeCP2– neurons (as indicated by staining for MAP2). Scale bars: 10 μm.

Neurons derived from both WT and HET mouse iPS cells are electrophysiologically active

An unbiased electrophysiology approach was taken to characterize the passive and active properties in the putative neurons derived from the WT and HET iPS cells. Whole-cell recordings were made from neuronally differentiated WT (n=95 cells) or HET (n=82 cells) iPS cells. Under current-clamp recording conditions, both WT (n=7) and HET cells (n=11) spontaneously generate fast action potentials, sensitive to the voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Figures 3a and b). The frequency of the spontaneous action potentials was not different between genotypes (Supplementary Figure 7). In addition, action potentials could be evoked by injecting depolarizing current (n=58 and 67 for WT and HET, respectively). These action potentials were sensitive to TTX in 9 of 10 WT cells tested and 7 of 7 HET cells (Figures 3a and b). These findings, together with immunocytochemical results, indicate that functional neurons are derived from both WT and HET iPS cells. iPS-derived cells showing spontaneous or depolarization-induced action potentials were thus operationally defined as neurons for the remainder of this study. iPS-derived cells that did not generate action potentials were considered to be non-neuronal cells. Such cells may include astrocytes, as staining differentiated iPS cell cultures with the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein indicated the presence of this cell type in the cultures (Supplementary Figure 8).

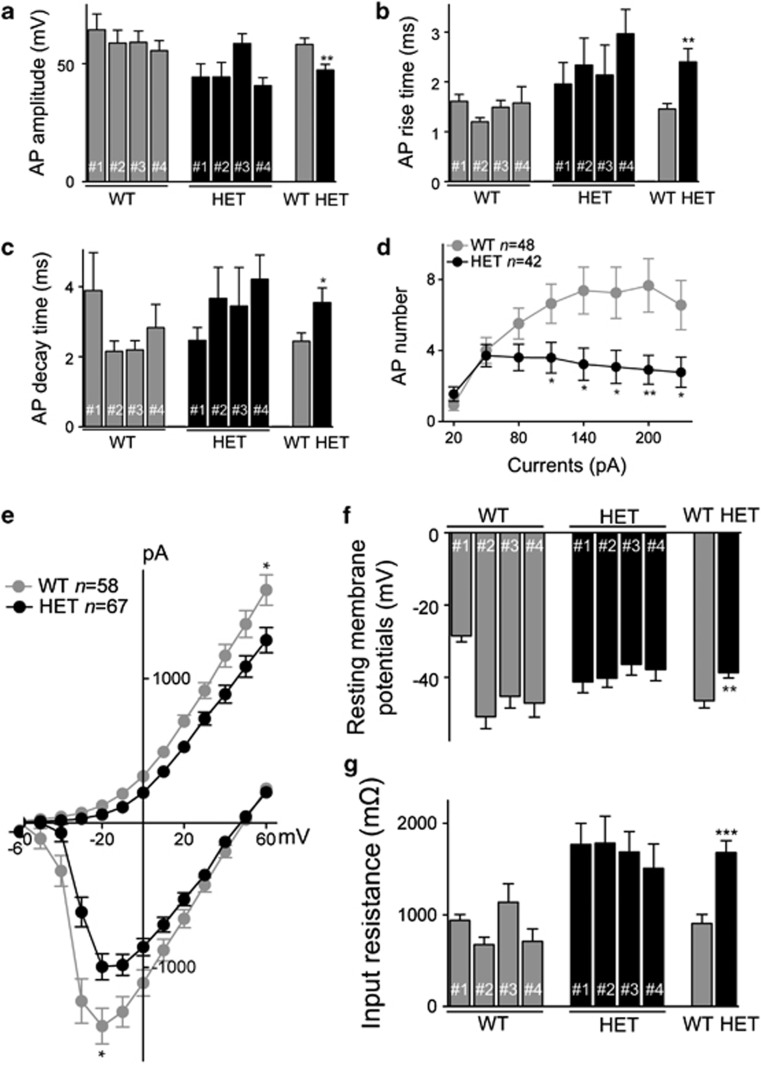

Neurons derived from HET iPS cells display alterations in action potential characteristics

For the iPS-derived neurons, we next assessed whether the presence of the Mecp2308 allele affected the functional properties of action potentials. No significant difference was observed in the threshold of action potential generation between WT (n=48) and HET iPS cell-derived neurons (n=42) (Supplementary Figure 9a). However, the action potential amplitude in the HET neurons was significantly less than that in WT neurons (Figure 4a). Furthermore, the rise time (Figure 4b), decay time (Figure 4c) and duration (Supplementary Figure 9b) of the action potentials were significantly longer in HET iPS-derived neurons. In addition, the number of action potentials generated by injecting current steps was significantly decreased in HET relative to WT (Figure 4d). Taken together, these findings indicate that HET iPS cell-derived neurons exhibit dysfunction in the generation of action potentials, and that compared with WT, the evoked action potentials have smaller amplitude and a longer time course.

Figure 4.

Action potential characteristics, voltage-activated currents, resting membrane potential and input resistance are altered in HET iPS-derived neurons compared with WT iPS-derived neurons. (a) Histogram showing average amplitude of action potentials in WT iPS-derived neurons (grey) and HET (black) iPS-derived neurons. The groups of bars on the left and middle show the four individual WT and HET sublines, respectively. Numbers of cells were 2, 11, 21 and 14 for WT #1,2,3,4, and 8, 9, 12 and 13 for HET #1,2,3,4, respectively. On right are the overall averages for WT (n=48 cells) and HET (n=42 cells). (b) Histogram of average rise time of action potentials in the WT and HET sublines and overall groups as in panel a. (c) Histogram of average decay time of action potentials in the WT and HET sublines and overall groups as in panel a. (d) A plot depicting the numbers of evoked action potentials elicited by depolarizing current steps from the overall groups of WT and HET sublines. The current steps were from +20 pA to +230 pA in +30-pA increments. (e) A plot showing average current–voltage relationships in WT compared with HET iPS-derived neurons. Recordings were made in voltage-clamp mode (holding potential −70 mV) and currents were elicited by a series of voltage steps from −60 to +60 mV. Early inward and late outward currents were measured as illustrated in the traces in Supplementary Figure 10. Maximum average inward currents and maximum outward currents of WT were compared with those of HET, *P<0.05. (f) Histogram of average resting membrane potentials in the WT and HET sublines and overall groups. (g) Histogram of average input resistance in the WT and HET sublines and overall groups. For resting membrane potential and input resistance, n=3, 15, 26 and 14 for WT #1,2,3,4, and n=13, 18, 18 and 18 for HET #1,2,3,4, respectively; totals WT (n=58) and HET (n=67). In this and all Figures, data points are mean ± s.e.m.; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

HET iPS cell-derived neurons have altered passive and active membrane properties

The alterations in action potential properties suggest that disturbances in the functional expression of voltage-gated Na+ and/or K+ channels may be present in HET iPS cell-derived neurons, as these types of ion channels make primary contribution to action potential generation. We therefore directly investigated Na+ and K+ currents evoked in WT and HET iPS cell-derived neurons by a series of depolarizing voltage steps from −60 mV to +60 mV (in 10-mV increments). Both inward and outward currents evoked by these voltage steps were greatly decreased in HET iPS cell-derived neurons compared with WT (Figure 4e, Supplementary Figure 10). These results indicate that MeCP2 deficiency in neurons generated from HET iPS cells leads to reductions in Na+ and K+ currents.

In addition to examining active membrane responses evoked by injecting current, the passive membrane properties of neurons derived from the different WT and HET iPS cells were also assessed. On average, resting membrane potentials of HET iPS cell-derived neurons (n=67) were depolarized with respect to those of neurons from WT (n=58) (Figure 4f). The only outliers in this and other electrophysiology criteria are the WT #1 (n=3) and HET #1 cells (n=13) in which the fewest cells were analyzed. This is in contrast to the consistent results obtained from the other three sublines of each genotype, where recordings were made from larger cell numbers. In addition, input resistance was significantly higher in HET compared with WT neurons (Figure 4g). Collectively, these data indicate that many passive and active membrane properties are altered in HET as compared with WT iPS cell-derived neurons. In contrast to the iPS-derived neurons, neither average resting membrane potential nor input resistance in non-neuronal HET cells were different from those in WT cells (Supplementary Figures 11a and b). Thus, the differences in electrophysiological characteristics between HET and WT cells are specific to neurons and not a common feature of all iPS-derived cells.

Spontaneous mEPSC event frequency is decreased in HET iPS cell-derived neurons

Another cardinal property of neurons, in addition to generating Na+-dependent action potentials, is forming functional synaptic connections. To assess whether MeCP2308 iPS cell-derived neurons form normal functional synaptic connections, we took advantage of the fact that synapses show action potential-independent release of quanta of neurotransmitter.27 As the differentiation protocol was biased towards producing glutamatergic neurons, we looked for and analyzed spontaneously occurring miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) with voltage-clamp recordings done in the presence of TTX, and blockers of GABAA and glycine receptors. When the membrane potential was held at −60 mV, spontaneously occurring inward currents were observed that exhibited two components (Supplementary Figures 12a and b): a fast component sensitive to AMPA receptor blocker 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, and a slow component sensitive to NMDA receptor blocker DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid. Thus, both WT and HET neurons show glutamatergic mEPSCs, indicating that the cells are competent to form functional excitatory synaptic connections.

In comparing the properties of mEPSCs in WT and HET neurons, we found that the frequency of mEPSC events was significantly higher in WT iPS cell-derived neurons than in HET (Supplementary Figure 12d). In contrast, there were no differences detected in mEPSC amplitude (Supplementary Figure 12c). Together, the decrease in mEPSC frequency in the absence of a change in mEPSC amplitude suggests that there is a synaptic dysfunction—decreased synaptic number or release probability—at glutamatergic synapses in HET iPS cell-derived neurons.

Neurophysiology phenotypes are reproducible among multiple mutant iPS cell lines and due to Mecp2 deficiency

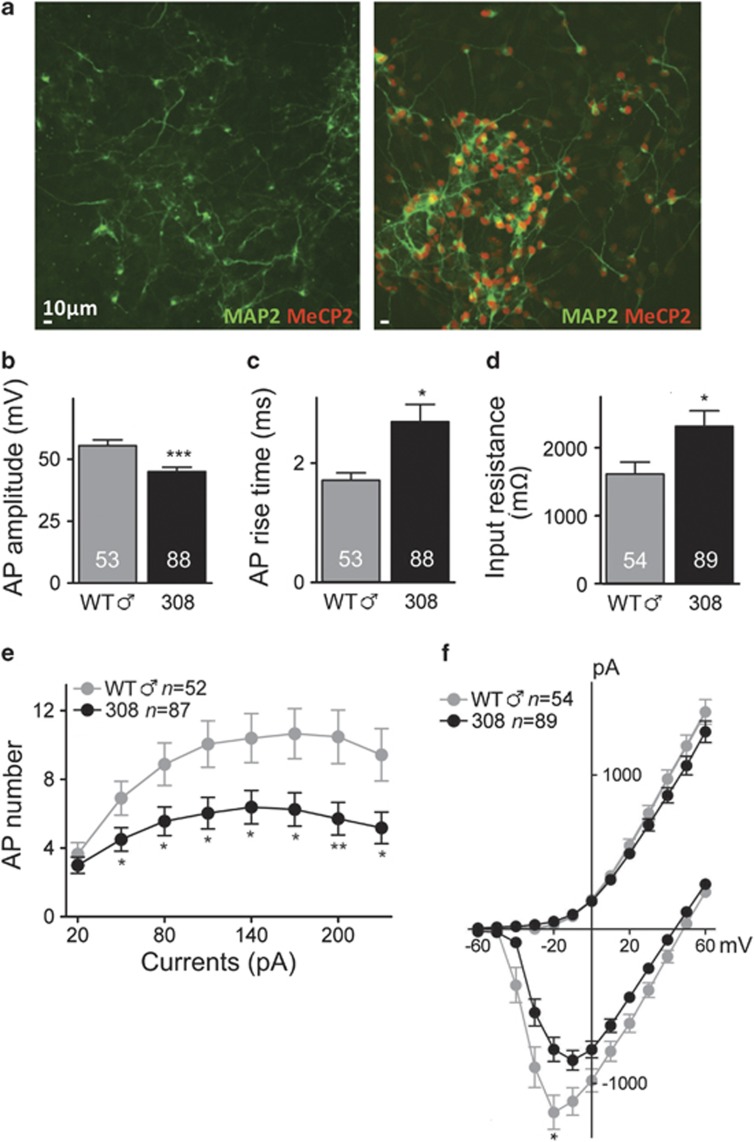

To determine whether the cellular phenotypes observed in HET iPS cell-derived neurons were or were not cell line-specific or due to particular transgene integration sites, we generated and analyzed an additional seven hemizygous male mutant and five WT male iPS cell lines (Supplementary Figure 13). In this way, we assessed not only differences across lines, but also the effect of reprogramming neurons in the absence of a mosaic culture environment. Following reprogramming, Mecp2308/y and WT Mecp2+/y lines (308 and WT ♂, respectively, in the figures) were karyotypically normal and maintained the genotype of their parental somatic cells (Supplementary Figures 14a and b). These functionally pluripotent lines (Supplementary Figures 15, 16 and 17) were directed to differentiate as described above into MAP2-positive neurons. Immunocytochemical staining confirmed the presence of full-length MeCP2 in Mecp2+/y cells and its absence in Mecp2308/y cells (Figure 5a). In electrophysiological recordings, hemizygous male neurons had significant changes compared with WT male neurons in: input resistance, action potential amplitude, rise time, voltage-activated Na+ currents and the number of action potentials generated by injecting depolarizing current steps (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 18). While other parameters were not significantly different in Mecp2+/y versus Mecp2308/y neurons (Supplementary Figure 19), the majority of the electrophysiological aberrations observed in HET iPS cell-derived neurons were also seen in Mecp2308/y cells. Taken together, our results from multiple cell lines are consistent with the idea that Mecp2 deficiency results in less excitable neurons.

Figure 5.

Hemizygous Mecp2308/y male iPS-derived neurons show deficits in action potential characteristics, excitability and voltage-activated Na+ currents. (a) Neuronally differentiated male ♂ WT (Mecp2+/y; WT ♂) and mutant (Mecp2308/y; 308) iPS-derived cells express MAP2. Immunofluorescence analysis using a C-terminal antibody unable to detect the C-terminal truncated MeCP2308 protein reveals that mutant iPS cell line 308 #1 is negative for MeCP2 expression (left). In contrast, WT ♂ #11 iPS-derived neurons express MeCP2 in all MAP2+ cells (right). Scale bars: 10 μm. (b) Histogram shows average action potential amplitude for total iPS-derived cell lines of WT ♂ (grey, n=53 neurons) and 308 (black, n=88 neurons). (c) Average action potential rise time from WT ♂ iPS-derived neurons and 308 iPS-derived neurons. (d) Average input resistances of WT ♂ and 308 iPS-derived neurons. (e) The plot shows average numbers of action potentials evoked by a series of depolarizing current steps from WT ♂ and 308 iPS-derived neurons. (f) A plot of average current–voltage relationships in WT ♂ compared with 308 iPS-derived neurons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed whether iPS cell technology could be extended into mouse models focusing on delineating the pathophysiology of RTT. To do this, we turned to the well-characterized monogenic Mecp2308 mouse model, where underlying neuronal phenotypes have been described and many behavioural impairments reminiscent of the human disorder are recapitulated. After extensive characterization of their pluripotency, the HET lines were differentiated into functional glutamatergic neurons that displayed several electrophysiological differences compared with neuronally differentiated WT iPS cells. The accumulation of electrophysiology from cumulatively larger neuron numbers allowed a more thorough investigation of neuronal dysfunction compared with previous studies of disease phenotyping using differentiated iPS cells.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35

Recording from almost 400 cells in total, we found common phenotypes in the HET-derived and Mecp2308/y-derived neurons: higher input resistance, decreased action potential amplitude, prolonged rise time, diminished voltage-activated Na+ currents and a reduction in the number of action potentials generated by injecting depolarizing current steps. Together, these differences give a picture of neurons lacking MeCP2 as deficient in intrinsic excitability and, from the lowered mEPSC frequency in the HET neurons, deficient in excitatory synaptic transmission. Deficiencies in intrinsic excitability and excitatory synaptic transmission have been reported in MeCP2-lacking neurons in vivo and in vitro, although there is variability in the abnormalities in different brain regions.5, 36

As all our findings in neurons derived from iPS cells recapitulate changes observed in some neurons in or directly from the brain, the iPS cell system is a representative model of the neuronal cellular and synaptic defects in RTT. Besides being a system that can be used to study neuron function, iPS cells allow the possibility of studying disease processes in a setting more amenable to genetic rescue or pharmacological intervention compared with intact mice or primary neurons. Further, as RTT is postulated to be a consequence of a failure of neurons to mature properly, the iPS cell system is ideal for future in-depth analyses of the developmental time course of mutant neural progenitor differentiation and neuron maturation, experiments that are more technically challenging in whole mice.

The common responsiveness of the HET cultures is somewhat surprising, as these cells contain a mixture of neurons expressing either WT or truncated MeCP2 due to random X-chromosome inactivation. Despite this, we recorded electrophysiological characteristics across differentiated iPS cell lines that were seemingly homogeneous, suggesting strongly that the lack of MeCP2 exerts both cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous influences in these mixed cultures. This is not unprecedented, as previous studies using human iPS cell-derived MeCP2-deficient neurons17, 18, 19, 21 found a similar outcome, and recent reports have also now demonstrated that Mecp2-deficient glia provide non-cell autonomous influences on neuron properties.37, 38, 39, 40 It is possible that Mecp2-mutant cells in the culture may contribute a non-cell autonomous effect on WT cells and on overall neuronal network function. Ballas et al.37 also demonstrated that conditioned media from WT astrocytes rescued some aspects of aberrant neurophysiology in mutant neurons, and in accordance, we observed modest improvements in electrophysiological phenotypes when WT-conditioned media was transferred onto 308 cultures (Supplementary Figure 20). Alternatively, the deficiencies in excitatory synaptic function may also reflect a deficit in overall connectivity between mosaic HET neurons. Collectively, these influences may explain why the HET neurons do not appear to behave in a bimodal manner based on whether they express WT or truncated MeCP2. To avoid non-cell autonomous effects or connectivity differences from HET neurons, hemizygous male iPS cell lines were generated, neuronally differentiated and assayed using the same electrophysiological paradigms. The results show strong consistency with the HET sublines, and thus strongly support our conclusion that the phenotypes we observe reflect RTT pathogenesis, and not spurious cell line-specific outcomes.

Previous reports illustrate that Mecp2 deficiency in the brain results in subtle alterations in synaptic responsiveness, at least some of which we now show can be recapitulated in neurons generated from mouse iPS cells.5, 36 However, our work further shows that MeCP2 is required for iPS cell-derived neurons to develop proper intrinsic excitability as seen in the decreased numbers of action potentials generated in response to directly stimulating the neurons by injecting current. This decrease in excitability indicates that MeCP2-deficient neurons are impaired in encoding information into action potentials and in propagating that information to other neurons. The reduced intrinsic excitability may be explained by our observation of decreased Na+ currents in the mutant neurons. The decrease in Na+ currents may be due to reduced number or function of Na+ channels at the cell surface. Interestingly, neurons differentiated from human RTT–iPS cells have lower expression of messenger RNA for the Na+ channels SCN1A and SCN1B.19 Although the mechanism through which the changes in Na+ current manifests remains to be established, our results show clearly that the presence of functional MeCP2 is required for the normal ontogeny of neuron development and signalling. Further, we identify a current deficit that can be targeted in future drug screens using automated cell-based electrophysiology systems for studies of ion channel function. These observed neurophysiological alterations may contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of a variety of additional MECP2-associated neuropsychiatric disorders.

In summary, we provide the first account of the neuronal differentiation of iPS cells generated from a mouse model of RTT. To our knowledge, this is the first instance in which such neurons have been generated from any mouse model of a neurological disorder, and thus our results provide a strong basis for the use of neuronally differentiated iPS cells derived from defined mouse models in future studies that aim to elucidate pathophysiological mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Ontario Human iPS and SickKids ES Cell Facilities for infrastructure/reagents, and TCAG for karyotyping. We thank Drs Freda D Miller and Denis Gallagher for primary neurons, Andreea Norman for technical advice, Drs Simon Beggs, Daniel Bosch, Michael E. Hildebrand and Graham M Pitcher for their generous help, and Dr Amy P Wong and the Ellis lab for helpful discussions on the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-102649 to JE and MWS, and IG1-94505 to JE). MWS is an HHMI International Research Scholar, holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair, and is the Anne and Max Tanenbaum Chair in Molecular Medicine at the Hospital for Sick Children. NF is supported by an Ontario Council of Graduate Studies Master's Autism Scholars Award, the Ontario Student Opportunity Trust Funds Hayden Hantho Award, and a Banting & Best Doctoral Research Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg B, Aicardi J, Dias K, Ramos O. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett's syndrome: report of 35 cases. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:471–479. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung BP, Jugloff DG, Zhang G, Logan R, Brown S, Eubanks JH. The expression of methyl CpG binding factor MeCP2 correlates with cellular differentiation in the developing rat brain and in cultured cells. J Neurobiol. 2003;55:86–96. doi: 10.1002/neu.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R. Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet. 2001;27:327–331. doi: 10.1038/85906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfa G, Percy AK, Pozzo-Miller L. Experimental models of Rett syndrome based on Mecp2 dysfunction. Exp Biol Med. 2011;236:3–19. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Chen H, Samaco RC, Xue M, Chahrour M, Yoo J, et al. Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypes and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature. 2010;468:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nature09582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CW, Yeung WL, Ko CH, Poon PM, Tong SF, Chan KY, et al. Spectrum of mutations in the MECP2 gene in patients with infantile autism and Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2000;37:E41. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.12.e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Wolpert CM, Ravan SA, Shahbazian M, Ashley-Koch A, Cuccaro ML, et al. Identification of MeCP2 mutations in a series of females with autistic disorder. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(02)00624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauck SM, Lindsay S, Beyer KS, Splitt M, Burn J, Poustka A. A mutation hot spot for nonspecific X-linked mental retardation in the MECP2 gene causes the PPM-X syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1034–1037. doi: 10.1086/339553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Lazar G, Couvert P, Desportes V, Lippe D, Mazet P, et al. MECP2 mutation in a boy with language disorder and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:148–149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.148-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jugloff DG, Logan R, Eubanks JH. Breeding and maintenance of an Mecp2-deficient mouse model of Rett syndrome. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;154:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta A, Cheung AY, Farra N, Vijayaragavan K, Séguin CA, Draper JS, et al. Isolation of human iPS cells using EOS lentiviral vectors to select for pluripotency. Nat Methods. 2009;6:370–376. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta A, Cheung AY, Farra N, Garcha K, Chang WY, Pasceri P, et al. EOS lentiviral vector selection system for human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1828–1844. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MCN, Carromeu C, Acab A, Yu D, Yeo GW, Mu Y, et al. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AY, Horvath LM, Grafodatskaya D, Pasceri P, Weksberg R, Hotta A, et al. Isolation of MECP2-null Rett syndrome patient hiPS cells and isogenic controls through X-chromosome inactivation. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2103–2115. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KY, Hysolli E, Park IH. Neuronal maturation defect in induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14169–14174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018979108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amenduni M, De Filippis R, Cheung AY, Disciglio V, Epistolato MC, Ariani F, et al. iPS cells to model CDKL5-related disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:1246–1255. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananiev G, Williams EC, Li H, Chang Q. Isogenic pairs of wild type and mutant induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines from Rett syndrome patients as in vitro disease model. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian M, Young J, Yuva-Paylor L, Spencer C, Antalffy B, Noebels J, et al. Mice with truncated MeCP2 recapitulate many Rett syndrome features and display hyperacetylation of histone H3. Neuron. 2002;35:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibel M, Richter J, Schrenk K, Tucker KL, Staiger V, Korte M, et al. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into a defined neuronal lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/nn1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibel M, Richter J, Lacroix E, Barde YA. Generation of a defined and uniform population of CNS progenitors and neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1034–1043. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maherali N, Sridharan R, Xie W, Utikal J, Eminli S, Arnold K, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N, Macklis JD. MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatt P, Katz B. Spontaneous subthreshold activity at motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 1952;117:109–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr, Mattis VB, Lorson CL, Thomson JA, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Papapetrou EP, Kim H, Chambers SM, Tomishima MJ, Fasano CA, et al. Modelling pathogenesis and treatment of familial dysautonomia using patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2009;461:402–446. doi: 10.1038/nature08320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'Souza SL, Ang YS, Schaniel C, Lee DF, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, Jung CB, Lam JT, Bott-Flügel L, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lian Q, Zhu G, Zhou F, Sui L, Tan C, et al. A human iPSC model of Hutchinson Gilford Progeria reveals vascular smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cell defects. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Caspi O, Winterstern A, et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cui N, Wu Z, Su J, Tadepalli JS, Sekizar S, et al. Intrinsic membrane properties of locus coeruleus neurons in Mecp2-null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C635–C646. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00442.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas N, Lioy DT, Grunseich C, Mandel G. Non-cell autonomous influence of MeCP2-deficient glia on neuronal dendritic morphology. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:311–317. doi: 10.1038/nn.2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezawa I, Swanberg S, Harvey D, LaSalle JM, Jin LW. Rett syndrome astrocytes are abnormal and spread MeCP2 deficiency through gap junctions. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5051–5061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0324-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N, Macklis JD. MeCP2 functions largely cell-autonomously, but also non-cell-autonomously, in neuronal maturation and dendritic arborization of cortical pyramidal neurons. Exp Neurol. 2010;222:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioy DT, Garg SK, Monaghan CE, Raber J, Foust KD, Kaspar BK, et al. A role for glia in the progression of Rett's syndrome. Nature. 2011;475:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature10214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.