Abstract

Addition of hydrogen peroxide to cultured astrocytes induced a rapid and transient increase in the expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras. Pull-down experiments with the GTP-Ras-binding domain of Raf-1 showed that oxidative stress substantially increased the activation of Ha-Ras, whereas a putative farnesylated activated form of Ki-Ras was only slightly increased. The increase in both Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras was insensitive to the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide, and was occluded by the proteasomal inhibitor, MG-132. In addition, exposure to hydrogen peroxide reduced the levels of ubiquitinated Ras protein, indicating that oxidative stress leads to a reduced degradation of both isoforms through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Indeed, the late reduction in Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras was due to a recovery of proteasomal degradation because it was sensitive to MG-132. The late reduction of Ha-Ras levels was abrogated by compound PD98059, which inhibits the MAP kinase pathway, whereas the late reduction of Ki-Ras was unaffected by PD98059. We conclude that oxidative stress differentially regulates the expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in cultured astrocytes, and that activation of the MAP kinase pathway by oxidative stress itself or by additional factors may act as a fail-safe mechanism limiting a sustained expression of the potentially detrimental Ha-Ras.

1. Introduction

An increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several CNS disorders including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, acute and chronic cerebrovascular disorders, and brain ageing. In particular, oxidative stress in the CNS occurs after ischemic, traumatic, or excitotoxic insults when the excessive generation of ROS overwhelms the intracellular antioxidant capacity [1]. Neurons are highly sensitive to oxidative damage, whereas astrocytes exert a protective function acting as cell scavengers and producing neurotrophic factors in response to ROS [2–6]. Astrocytes respond to ROS with the activation of MAP kinases (MAPKs), including the extracellular signal-regulated kinases ERK1/2, JUN kinases (JNKs), and p38 MAPKs [7, 8]. The monomeric GTP-binding protein, Ras, has an established role in activating these pathways and has been implicated in the cellular response to oxidative stress [9, 10].

Mammalian cells contain three ubiquitously expressed Ras isoforms, Ha-, Ki-, and N-Ras that share a high degree of structural homology [11]. Ha- and Ki-Ras generate opposing effects on the redox state of cells in heterologous expression systems. Ki-Ras exerts an antiapoptotic activity mediated by Mn-superoxide dismutase (SOD), whereas Ha-Ras decreases tolerance to oxidative stress by a mechanism mediated by NADPH oxidase complex via ERK [12–14]. Expression and/or activation of Ras is regulated by ROS in fibroblasts [15] and Jurkat cells [16]. mRNA expression of Ha-, Ki-, and N-Ras has been reported in cultured mouse astrocytes [17]. However, how individual Ras isoforms react to oxidative stress in astrocytes is unknown.

We now report that hydrogen peroxide posttranslationally regulates the expression of Ha- and Ki-Ras in cultured astrocytes, and that regulation of Ha-Ras critically involves MAPK activation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Monoclonal antibody (Ab-3) anti-panRas and proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (carbobenzoxy-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-leucinal) were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany). The antibodies against Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras, ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2, anti-Ras antibody-conjugated beads H259, and anti-ubiquitin antibody (clone P4D1) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-β-actin antibody was from Sigma Aldrich (Milano, Italy). The peroxidase-conjugated (HRP) anti-rabbit, anti-mouse secondary antibodies and the ECL detection system were from Amersham-Pharmacia (Biothec, UK Limited). Fetal calf serum (FCS) and horse serum, trypsin-EDTA, and penicillin/streptomycin solutions were purchased from HyClone Europe Ltd. (Cramlington, UK); Modified Eagle's Medium (MEM) from Life Technologies (Milano, Italy). Nitrocellulose membrane PROTRAN was from Schleicher and Schuell (Germany). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Milano, Italy).

2.2. Primary Cultures of Astrocytes

Astrocyte cultures were prepared from the cerebral cortex of CD1 mice (Charles River Laboratories Italia, Calco (Lecco), Italy) as follows. Cortices were collected in growth medium (pyruvate-free minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 10% horse serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 10.000 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin), washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), dissociated with 0.05% trypsin for 20 min at 37°C, and then centrifuged (500 ×g for 10 min). The pellet was resuspended in growth medium containing 5 mM L-leucine methyl ester to limit microglia contamination and cells were plated (2 · 106/10 mL) on 100-mm Falcon culture dishes and incubated at 37°C in atmosphere of 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours later, the medium was changed with a growth medium lacking L-leucine methyl ester, and cultures were grown for 15–20 days. Confluent cultures contained >99% astrocytes and less than 0.1% microglia as shown by astrocyte staining with glial fibrillary acidic protein and microglia staining with the lectin Bandeiraea simplicifolia [18].

2.3. RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Two μL cDNA products (derived from 2.5 μg of total RNA) were amplified with 1 unit of Ampli Taq Gold (PE Applied Biosystems) in the buffer provided by the manufacturer (which does not contain MgCl2), and in the presence of the specific primers for Ha-, Ki-Ras, and actin (see below). The amount of dNTPs carried over from the reverse transcription reaction is fully sufficient for further amplification. Reactions were carried out in the Gene Amp PCR system 9600. A first cycle of 10 min at 95°C, 45 s at 65°C, and 1 min at 72°C was followed by 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 65°C, and 1 min at 72°C for 30 cycles. In these conditions none of the cDNAs analyzed reached a plateau at the end of the amplification protocol, that is, they were in the exponential phase of amplification, and the two sets of primers used in each reaction did not compete with each other. Each set of reactions always included a no-sample negative control. We usually perform a negative control containing RNA instead of cDNA to rule out genomic DNA contamination. The following primers were used: Hum v-Ha-Ras (forward) 5′-GTGACCTGGCTGCACGCACTG-3′; (reverse) 5′-CACTTGCAGCTCATGCAGCCG-3′; Hum c-K-Ras2B: forward 550 5′-TTG CCT TCT AGA ACA GTA GAC A −3′ 571; reverse 751 3′- TTA CAC ACT TTG TCT TTG ACT TC–5′ 729; β-actin: forward, 3′-TGAACCCTAAGGCCAACCGTG-5′; reverse, 3′-GCTCATAGCTCTTCTCCAGGG-5′.

2.4. Cell Transfection

To assess the specificity of Ha- and Ki-Ras antibodies, we have transiently transfected HEK-293 cells with mutant Ras constructs (constitutively active Ki-Ras and Ha-Ras carrying a Val-12 point mutation or a double Ki-Ras mutant carrying Val-12 and Ala-185 mutations-Cuda et al., [12]). HEK-293 cells were plated onto 100-mm Falcon dishes and grown in DMEM containing 10% FCS. One day after plating, cells were transfected with 10 μg of cDNA in serum-free medium using a Lipofectin reagent (Life Technology, GIBCO), according to manufacturer's instructions. Two hours later, cultures were switched into the growing medium and 24 hours were allowed for the detection of the transfected proteins.

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Cultured astrocytes or HEK-293 cells were washed with PBS and lysed for 15 min in ice-cold RIPA buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.5% DOC, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mg/mL aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin, and, in the ubiquitin experiments, supplemented with 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide, an inhibitor of deubiquitinating enzymes). Cell lysates were clarified at 13,000 r.p.m. for 30 min at 4°C and the cytosolic fraction was immediately frozen in liquid N2 for further analysis or subjected to immunoprecipitation procedures. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA). Proteins were separated on SDS polyacrylamide gels (7–15%) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were then blocked in Tris-buffered saline (50 mM TrisHCl, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 5%–10% nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA) and incubated with primary antibodies (anti-pan-Ras antibody, Ab-3, 1 : 500; anti-Ki-Ras antibody, 1 : 200; anti-Ha-Ras antibody, 1 : 400, all incubated overnight at 4°C; anti-β-actin, 1 : 1,000, incubated 2 h at room temperature; anti-ubiquitin P4D1 antibody, 1 : 1,000, incubated overnight at 4°C; anti-ERK1/2 and anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (1 : 1,000), incubated 2 h at room temperature). Blots were washed three times with PBS and then incubated for 2 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (all used at 1 : 5,000). Immunostaining was revealed by the ECL detection system (Amersham). The cytosolic fraction deriving from hydrogen peroxide-treated astrocytes was also processed for immunoprecipitation with anti-Ras conjugated beads (H259). One mg of lysate was incubated with 4 μg of antibody-conjugated beads for 2 h at 4°C. Then the beads were subjected to extensive wash with RIPA buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis with Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras antibodies.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrogen Peroxide Increased the Expression of p21Ras in Culture Astrocytes

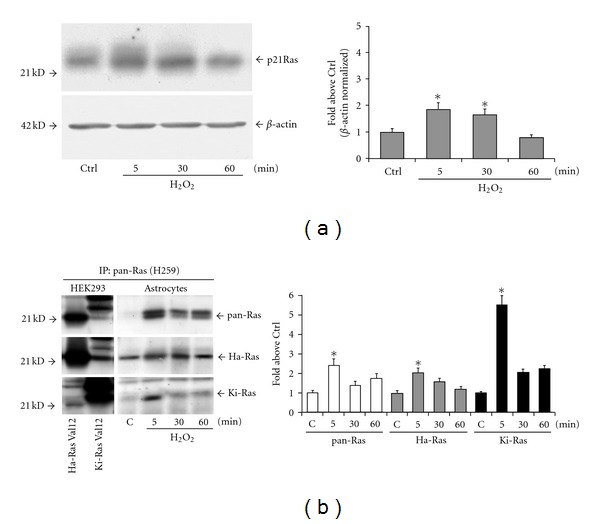

All experiments were carried out in confluent cultures grown in serum-containing medium for 15–20 days in vitro (DIV) and switched into serum-containing or not 1 mM hydrogen peroxide. Addition of hydrogen peroxide substantially increased pan-Ras levels after 5 and 30 min. Levels returned back to controls at 60 min (Figure 1(a)). We examined the protein expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras using polyclonal Santa Cruz antibodies. The two antibodies preferentially labelled the respective Ras isoform in immunoprecipitates from HEK-293 cells expressing constitutively active Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras Val-12 mutants (Figure 1(b)). The soluble fraction of cultured astrocytes immunoprecipitated with the H259 anti-Ras antibody was used for the study of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras protein expression. Addition of hydrogen peroxide induced a transient increase in the expression of both Ras isoforms, which peaked at 5 min and declined afterwards (Figure 1(b)). To measure the cytotoxic potential of the oxidative treatment, the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide] assay was carried out as described before [19] and reported in Supplementary Figure (S1) available online at doi:10.1155/2012/792705. We also checked for signalling cascade activated downstream by exposure to oxidative stress as reported in Figure S1.

Figure 1.

Oxidative stress induces a transient increase in the expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in cultured astrocytes. The kinetics of total Ras expression in control cultures and in cultures exposed to 1 mM hydrogen peroxide is shown in (a). The growing medium was switched into fresh medium and added of hydrogen peroxide. In control cultures, Ras expression was very low at 5 min and did not change at 30 or 60 min after the medium switch. Only control values at 5 min are show (Ctrl). Values shown in the graph are means ± SEM of 3 determinations. *P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA + Fisher's PLSD) versus Ctrl. Immunoblot analysis with Ha-Ras ad Ki-Ras antibodies carried out in HEK-293 cells expressing Val-12 Ha-Ras or Val-12 Ki-Ras is shown in (b). Note that the antibodies used preferentially, but not exclusively, labelled the respective Ras isoform. Expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in cultures exposed to hydrogen peroxide for 5, 30, or 60 min is shown in (b). Note that immunoblots were carried out on pan-Ras immunoprecipitates. Values were calculated as per cent of Ctrl and are means ± SEM of 4 determinations. P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA + Fisher's PLSD) versus the respective values at 5 (∗) or 30 (#) min.

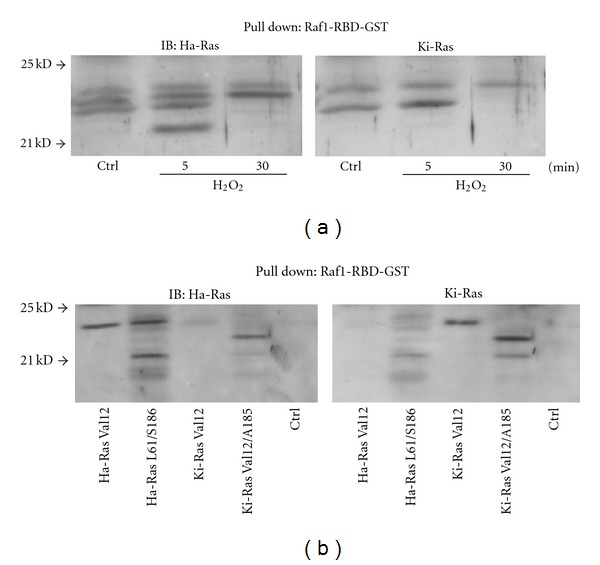

Downstream signalling by Ras is engaged when the protein is in the GTP-bound state. The GTP-bound form of Ras was pulled down from total fresh lysates of cultured astrocytes using the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Ras binding domain (RDB) fusion protein containing residues 1–149 of Raf-1 [20]. Total active Ras (Ras-GTP) collected on Raf1-RBD beads was probed with anti-Ha-Ras and anti-Ki-Ras antibodies. Levels of 21 kDa GTP-bound Ha-Ras were undetectable in control cells and transiently increased after a 5-min exposure to hydrogen peroxide (Figure 2(a)). A faint 25 kDa band was detected in pull-down experiments using anti-Ki-Ras antibodies. The intensity of this band slightly increased after a 5-min exposure to hydrogen peroxide, and declined afterwards (Figure 2(a)). To further examine the nature of the activated 25 KDa band of Ki-Ras, we carried out a pull-down experiment using lysates from HEK-293 cells expressing a constitutively active form of Ki-Ras (the Val-12 mutant) or the same form carrying an additional mutation (Ala-185) that prevents farnesylation. The 25 kDa band was detectable in cells expressing Val-12 Ki-Ras, but not in cells expressing Val-12/Ala-185 (Figure 2(b)), suggesting that this band corresponds to farnesylated Ki-Ras. Accordingly with others [21], we found that Ki-Ras migrates more slowly than Ha-Ras in SDS-PAGE gels.

Figure 2.

Expression of GTP-bound Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in cultured astrocytes exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Total active GTP-bound Ras was collected on Raf1-RBD beads and probed with Ha-Ras or Ki-Ras antibodies on the same membrane. Note in (a) that a 21 kDa band of GTP-bound Ha-Ras appeared after 5 min of exposure to hydrogen peroxide and disappeared afterwards. The immunoblot in (a) shows the putative activated form of Ki-Ras, which is present as a faint band at 25 kDa in control cultures, and slightly increased at 5 min after hydrogen peroxide. This band might correspond to a GTP-bound farnesylated form of Ki-Ras because it was present in HEK-293 cells expressing Val-12 Ki-Ras, but not in cells expressing a Ki-Ras mutant (Val-12/Ala-185), which cannot be farnesylated (b). All immunoblots were repeated twice with similar results.

3.2. Posttranslational Regulation of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras by Hydrogen Peroxide in Cultured Astrocytes: A Distinct Role for the Ubiquitin/Proteasome Pathway and MAP Kinase Activation

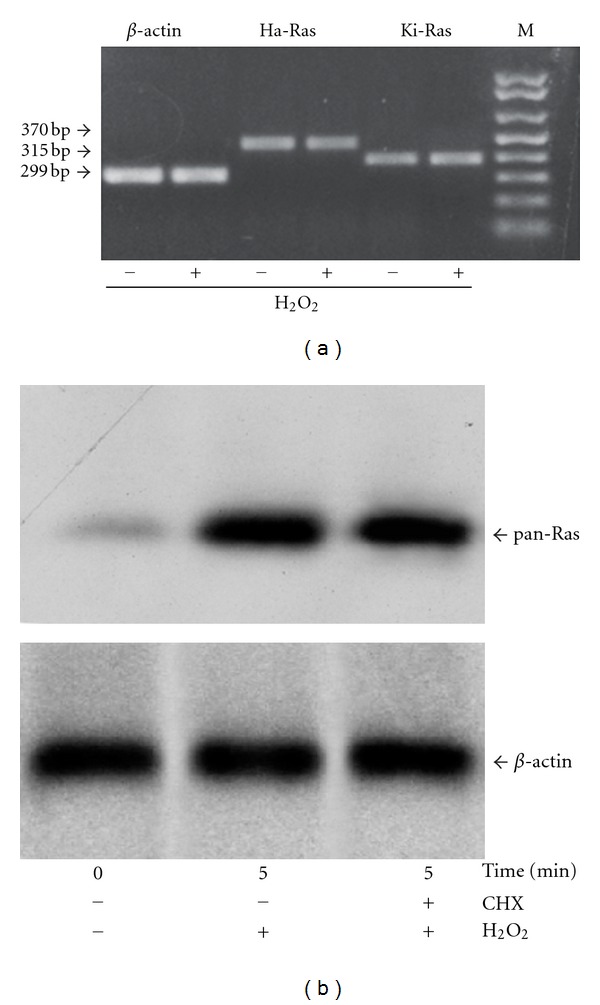

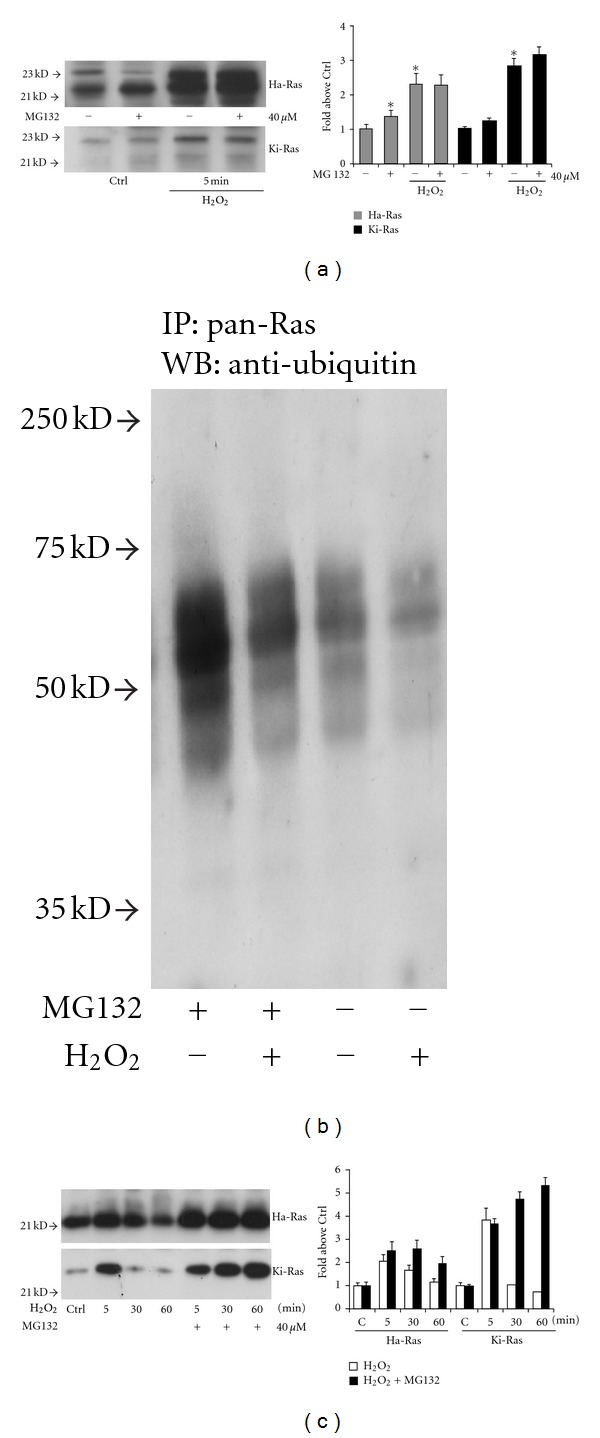

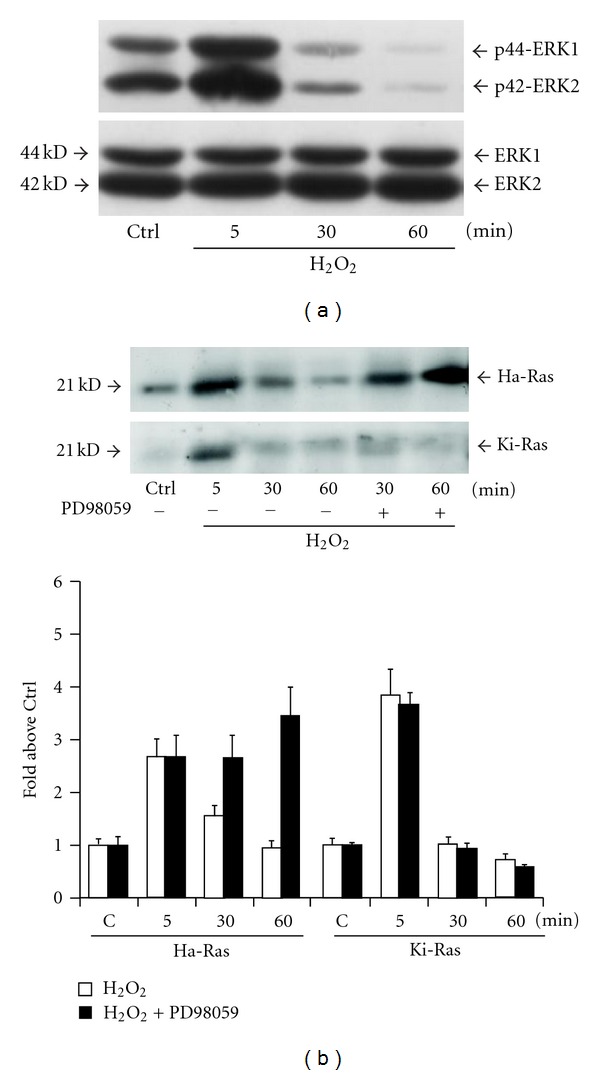

To underscore the nature of the increased expression of Ras in response to hydrogen peroxide, we first examined the transcripts of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras by semiquantitative RT-PCR. No apparent changes were detected in Ha-Ras or Ki-Ras mRNA levels after 5–30 min incubations with hydrogen peroxide (data at 5 min are shown in Figure 3(a)). We therefore examined the expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras protein from cultures treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (10 μg/mL, applied to the cultures 15 min prior to hydrogen peroxide). Treatment with cycloheximide did not affect the increase in Ha-Ras or Ki-Ras levels induced by hydrogen peroxide (Figure 3(b)). Taken together, these data indicate that Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras proteins are posttranslationally regulated by short-term stimulation with hydrogen peroxide in cultured astrocytes. We then examined the involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in the regulation of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras using the compound MG-132 (40 μM, added 15 min prior to hydrogen peroxide). MG-132 acts as a reversible inhibitor of the 26S subunit of the proteasome [22, 23]. The increase in Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras induced by a combined application of MG-132 and hydrogen peroxide was less than additive (Figure 4(a)), suggesting that hydrogen peroxide reduces Ras degradation through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Hydrogen peroxide might specifically reduce ubiquitination of Ras, as suggested by immunoblot analysis of ubiquitinated proteins in pan-Ras immunoprecipitates. Figure 4(b) shows that hydrogen peroxide reduced Ras ubiquitination particularly when the expression of ubiquitinated Ras was amplified by exposure to MG-132. Ubiquitin immunoreactivity in Ras immunoprecipitates appeared as a high molecular weight smear, suggesting that Ras was polyubiquitinated. This diverges from data reported with recombinant Ha-Ras in CHOK1 cells, in which the protein is mono- or diubiquitinated [24]. We also examined whether a reactivation of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway could be responsible for the decline of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras observed after 30- or 60-min exposure to hydrogen peroxide. This decline was sensitive to MG-132 (Figure 4(c)), showing the involvement of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Thus, addition of hydrogen peroxide to cultured astrocytes causes a transient increase in the protein expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras, which likely depends on a reduced protein ubiquitination. We then examined whether the MAPK pathway, which is ubiquitously activated by Ras ([25–28], is involved in the delayed reduction in Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras levels in astrocytes exposed to oxidative stress. Addition of hydrogen peroxide to cultures for 60 minutes induced a transient increase in the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2, which was substantial at 5 min (Figure 5(a)). We then examined the kinetics of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras expression in cultures treated with the MEK inhibitor, PD98059, and exposed to hydrogen peroxide. The presence of PD98059 affected neither the early increase in the expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras nor the delayed reduction in the expression of Ki-Ras. In contrast, pharmacological inhibition of the MAPK pathway abolished the delayed reduction in the expression of Ha-Ras. In cultures treated with PD98059 combined with hydrogen peroxide, levels of Ha-Ras at 30 and 60 min were as high as those detected at 5 min (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 3.

Posttranslational regulation of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras by hydrogen peroxide in cultured astrocytes. RT-PCR analysis of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras mRNA in control astrocytes (−) and in astrocytes treated with hydrogen peroxide for 5 min (+) is shown in (a). Immunoblot analysis of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in pan-Ras immunoprecipitates from cultures pretreated for 15 min with cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/mL) and then exposed to hydrogen peroxide for 5 min is shown in (b). Note that CHX did not affect the rapid increase in Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras levels induced by hydrogen peroxide. The immunoblot has been repeated twice with identical results.

Figure 4.

Role of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway in the posttranslational regulation of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras by hydrogen peroxide. Immunoblot analysis of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in pan-Ras immunoprecipitates in cultures pretreated for 15 min with the proteasomal inhibitor, MG-132 (40 μM), and then challenged with hydrogen peroxide for 5 min is shown in (a). Values are expressed as per cent of controls and represent the means + SEM of 3 determinations. Note the lack of additivity between MG-132 and hydrogen peroxide in increasing Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras levels. Ubiquitin immunoreactivity in pan-Ras immunoprecipitates from cultures treated with MG-132 and/or hydrogen peroxide is shown in (b). Note that a 5-min treatment with hydrogen peroxide reduces protein ubiquitination both in the absence and presence of MG-132. The temporal profile of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras expression in cultures pretreated with MG-132 for 15 min and then challenged with hydrogen peroxide for 30 and 60 min is shown in (c). Expression after a 5-min exposure with hydrogen peroxide alone is also shown for comparison. Values are expressed as per cent of controls and are means ± SEM of 3 determinations. Note that pretreatment with MG-132 did not affect the late reduction in Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras expression.

Figure 5.

Activation of the MAPK pathway is required for the late reduction in Ha-Ras expression in cultured astrocytes challenged with hydrogen peroxide. Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2 in cultures exposed to hydrogen peroxide for 5, 30, or 60 min is shown in (a). The experiment was repeated twice with identical results. Immunoblot analysis of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in pan-Ras immunoprecipitates from cultures pretreated for 15 min with the MEK inhibitor, PD98059 (25 M), and then challenged with hydrogen peroxide for 30 or 60 min is in (b). Values are expressed as per cent of controls and represent the means ± SEM of 4 determinations. *P < 0.05 (Student's t test) versus the respective value obtained in the absence of PD98059. Values at 5 min with hydrogen peroxide alone are also shown for comparison.

4. Discussion

Our main findings are that (i) oxidative stress transiently increases the expression of p21Ras in astrocytes; (ii) the protein kinetics of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras are differentially regulated by the activation of MAPK in response to hydrogen peroxide. This aspect is not trivial because these two p21Ras isoforms subserve different, sometimes opposite, functions in various cell types although they apparently activate the same downstream signaling pathways. Transfection of Ha-Ras in human umbilical vein endothelial cells decreases tolerance to oxidative stress, whereas transfection of Ki-Ras is protective. While both effects are mediated by ERK1/2 activation, protection is encoded by a stretch of lysines at the C-terminus of Ki-Ras, which is not present in Ha-Ras [12]. In addition, a stable transfection with the Val-12 mutant of Ha-Ras generates reactive oxygen species by inducing the translocation of cytosolic NADPH oxidase and Rac to the membrane. All these effects are mediated by ERK1/2 activation [14]. Under particular conditions, Ki-Ras can also promote apoptotic cell death. This follows the activation of protein kinase C (PKC), which promotes rapid dissociation of Ki-Ras from the plasma membrane and association with the outer mitochondrial membrane, where phosphorylated Ki-Ras interacts with Bcl-XL [29]. It is noteworthy that activation of PKC stimulates NADPH oxidase and promotes reactive oxygen species formation in astrocytes [30]. Thus, there might be situations in which Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras converge in the induction of cell death.

In our astrocyte cultures, expression and GTP-bound activation of Ha-Ras was low under basal conditions, and increased substantially at early times (5 min) following exposure to hydrogen peroxide. Levels of Ki-Ras also transiently increased in response to hydrogen peroxide. A faint 25 kDa band, which might correspond to a farnesylated active form of Ki-Ras, was more intense at 5 min and disappeared at later times following hydrogen peroxide exposure. Thus, while we found a nice correlation between expression and activation of Ha-Ras, we do not know to what extent expression levels reflect the activation of Ki-Ras. Hydrogen peroxide induced an early posttranslational increase in Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras expression by inhibiting degradation through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. This is reminiscent of data obtained in fibroblasts, where platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) generates reactive oxygen species and stabilizes Ha-Ras by inhibiting proteasomal degradation [15]. Protein ubiquitination was reduced in Ras immunoprecipitates from astrocytes treated with hydrogen peroxide, which might be expected because the lysine residues of Ras that are normally polyubiquitinated can be deaminated by hydrogen peroxide [31]. The late reduction of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in cultures exposed to oxidative stress was due to a recovery of proteasome degradation, because it was affected by the proteasome inhibitor, MG-132. ERK1/2 activation was required for the late degradation of Ha-Ras, but, interestingly, not for the late activation of Ki-Ras. Thus, in astrocytes, activation of the MAPK pathway by oxidative stress [16] may prevent a sustained expression of the potentially harmful Ha-Ras without affecting the putative antiapoptotic Ki-Ras [12]. The relevance of this regulation for astrocyte damage associated with acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders is unknown, but these data raise the attractive possibility that the balance between cytotoxic and cytoprotective mechanisms may be influenced acting at upstream events (i.e., Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras expression) triggered by reactive oxygen species.

Supplementary Material

Signalling cascade activated downstream by exposure to oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Gemma Molinaro for careful technical assistance. The authors wish also to thank Professor Angela Santoni and Professor Enrico Avvedimento for their continuous advice.

References

- 1.Andersen JK. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence? Nature Medicine. 2004;10:S18–S25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka J, Toku K, Zhang B, Ishihara K, Sakanaka M, Maeda N. Astrocytes prevent neuronal death induced by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Glia. 1999;28:85–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199911)28:2<85::aid-glia1>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takuma K, Baba A, Matsuda T. Astrocyte apoptosis: implications for neuroprotection. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;72(2):111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts LT, Rathinam ML, Schenker S, Henderson GI. Astrocytes protect neurons from ethanol-induced oxidative stress and apoptotic death. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2005;80(5):655–666. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desagher S, Glowinski J, Premont J. Astrocytes protect neurons from hydrogen peroxide toxicity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(8):2553–2562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makar TK, Nedergaard M, Preuss A, Gelbard AS, Perumal AS, Cooper AJL. Vitamin E, ascorbate, glutathione, glutathione disulfide, and enzymes of glutathione metabolism in cultures of chick astrocytes and neurons: evidence that astrocytes play an important role in antioxidative processes in the brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;62(1):45–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62010045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberger J, Petrovics G, Buzas B. Oxidative stress induces proorphanin FQ and proenkephalin gene expression in astrocytes through p38- and ERK-MAP kinases and NF-κB. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;79(1):35–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tournier C, Thomas G, Pierre J, Jacquemin C, Pierre M, Saunier B. Mediation by arachidonic acid metabolites of the H2O2-induced stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase) European Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;244(2):587–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson TM, Sasaki M, Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Dawson VL. Regulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase and identification of novel nitric oxide signaling pathways. Progress in Brain Research. 1998;118:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Feldman AB, Klesse LJ, et al. Requirement for nitric oxide activation of p21ras/extracellular regulated kinase in neuronal ischemic preconditioning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(1):436–441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock JF. Ras proteins:different signals from different locations. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4(5):373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuda G, Paternò R, Ceravolo R, et al. Protection of human endothelial cells from oxidative stress: role of Ras-ERK1/2 signaling. Circulation. 2002;105(8):968–974. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santillo M, Mondola P, Serù R, et al. Opposing functions of Ki- and Ha-Ras genes in the regulation of redox signals. Current Biology. 2001;11(8):614–619. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serù R, Mondola P, Damiano S, et al. HaRas activates the NADPH oxidase complex in human neuroblastoma cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;91(3):613–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svegliati S, Cancello R, Sambo P, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor and reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulate Ras protein levels in primary human fibroblasts via ERK1/2: amplification of ROS and Ras in systemic sclerosis fibroblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(43):36474–36482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lander HM, Ogiste JS, Teng KK, Novogrodsky A. p21(ras) as a common signaling target of reactive free radicals and cellular redox stress. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(36):21195–21198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubio N. Interferon-gamma protects astrocytes from apoptosis and increases the formation of p21ras-GTP complex through ras oncogene family overexpression. Glia. 2001;33:151–159. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(200102)33:2<151::aid-glia1014>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dugan LL, Bruno VMG, Amagasu SM, Giffard RG. Glia modulate the response of murine cortical neurons to excitotoxicity: glia exacerbate AMPA neurotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15(6):4545–4555. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04545.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter-Landsberg C, Vollgraf U. Mode of cell injury and death after hydrogen peroxide exposure in cultured oligodendroglia cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1998;244(1):218–229. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann C, Martin GA, Wittinghofer A. Quantitative analysis of the complex between p21(ras) and the ras-binding domain of the human raf-1 protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(7):2901–2905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki AT, Carracedo A, Locasale JW, et al. Ubiquitination of K-Ras enhances activation and facilitates binding to select downstream effectors. Science Signaling. 2011;4(163, article ra13) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome-dependent and vacuolar pathways of protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(44):27280–27284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimm LM, Goldberg AL, Poirier GG, Schwartz LM, Osborne BA. Proteasomes play an essential role in thymocyte apoptosis. The EMBO Journal. 1996;15(15):3835–3844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jura N, Scotto-Lavino E, Sobczyk A, Bar-Sagi D. Differential modification of Ras proteins by ubiquitination. Molecular Cell. 2006;21(5):679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormick F. Raf: the holy grail of Ras biology? Trends in Cell Biology. 1994;4(10):347–350. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall MS. Ras target proteins in eukaryotic cells. The FASEB Journal. 1995;9(13):1311–1318. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.13.7557021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6(11):827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ory S, Morrison DK. Signal transduction: implications for Ras-dependent ERK signaling. Current Biology. 2004;14(7):R277–R278. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bivona TG, Quatela SE, Bodemann BO, et al. PKC regulates a farnesyl-electrostatic switch on K-Ras that promotes its association with Bcl-XL on mitochondria and induces apoptosis. Molecular Cell. 2006;21(4):481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abramov AY, Jacobson J, Wientjes F, Hothersall J, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Expression and modulation of an NADPH oxidase in mammalian astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(40):9176–9184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1632-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akagawa M, Suyama K. Oxidative deamination by hydrogen peroxide in the presence of metals. Free Radical Research. 2002;36(1):13–21. doi: 10.1080/10715760210167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Signalling cascade activated downstream by exposure to oxidative stress.