Abstract

Objectives

To identify teamwork behaviors associated with improving efficiency and quality of simulated resuscitation training.

Methods

Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial of trainees undergoing neonatal resuscitation training was performed. Trainees at a large academic center (n=100) were randomized to receive standard curriculum (n=36) versus supplemental team training curriculum (n=62). A two-hour team training session focused on communication skills and team behaviors served as the intervention. Outcomes of interest included resuscitation duration, time required to complete a simulated newborn resuscitation, and performance score, determined by evaluation of each of the team’s steps during simulated resuscitation scenarios.

Results

The teamwork behaviors assertion and sharing information were associated with shorter resuscitation duration and higher performance scores. Each additional use of assertion (per minute) was associated with a duration reduction of 41 s (95%CI: −71.5 to −10.2) and an increase in performance score of 1.6% (95%CI: 0.4 to 2.7). Each additional use of sharing information (per minute) was associated with a 14 s reduction in duration (95%CI: −30.4 to 2.9) and a 0.8% increase in performance score (95%CI: 0.05 to 1.5).

Conclusions

Teamwork behaviors of assertion and sharing information are two important mediators of efficiency and quality of resuscitations.

INTRODUCTION

The Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) is a standardized approach to newborn resuscitation that was developed to “facilitate acquisition of elemental content knowledge and technical skills necessary to resuscitate a newborn.”1. However, mastery of content and skills alone may not be adequate for optimizing the outcome of a resuscitation. Appropriate teamwork behaviors are also necessary to communicate and perform well in a high-stress, time-sensitive environment such as the delivery room or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) 2,3.

In 2004, The Joint Commission reviewed 109 cases of perinatal death and disability and identified communication issues as the root cause for majority (72%) of cases and recommended all health care organizations responsible for delivering newborns to “conduct team training in perinatal areas to teach staff to work together and communicate more effectively”4. Following this recommendation, NRP has indicated the need for integration of behavioral skills training and teamwork concepts into its training curriculum1.

We previously conducted a randomized trial of residents undergoing NRP training to test the effectiveness and feasibility of team training during the certification process5. Results indicated that team trained participants completed simulated resuscitation scenarios faster and exhibited teamwork behaviors more frequently, but with similar NRP performance scores5. While the team training intervention did not seem to have the expected positive impact of error reduction or better performance, we observed a wide variation in performance scores between teams, ranging from 50% to 87% (on a scale of 0–100%). It is unclear whether specific teamwork behaviors might have contributed to the variation in performance between teams, regardless of the team training intervention. In this secondary analysis, our objective is to further evaluate the teams’ use of teamwork behaviors and understand their role in mediating the performance of a team during resuscitation. In specific, our aim is to identify behaviors that are associated with faster completion of resuscitation scenarios and higher performance scores.

METHODS

Participants

First year trainees (interns) for the specialties of pediatrics, combined medicine-pediatrics, family medicine, emergency medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology, who have not been NRP certified previously, were eligible for study participation. Informed consent was obtained and consented candidates were randomly assigned to one of three groups: 1) Standard NRP with low-fidelity skills session (control group); 2) NRP with low-fidelity skills session and team training (intervention group); 3) NRP with high-fidelity skills session and team training (intervention group). Therefore, the control arm for this study consisted of approximately 1/3 of the total participants (36) and intervention arm, 2/3 of the participants (62). Within each arm of the study, participants were randomly divided into teams of 3–4 individuals.

Setting

The study was conducted at University of Texas Medical School at Houston from 2007 to 2008.

Intervention

A team training program was created to teach communication and teamwork behaviors that can be used in intense clinical scenarios requiring team coordination. This training program was presented prior to the initiation of standard NRP certification course to those randomized to the intervention arm. A two-hour session was conducted by a professional who is experienced in aviation and health care related team training (details presented previously5). The teamwork curriculum consisted of: (1) information about human error, including limitations of human performance and the epidemiology of error in medicine and neonatal resuscitation; (2) examples of specific communication behaviors (information sharing, inquiry, assertion, verbalizing intentions, workload management, vigilance, and leadership) used to prevent and manage error; (3) other methods for improving communication (using standard terminology, increasing clarity, repeating information, and sharing a mental model) and the SBAR model (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation); and (4) customized video clips and role-playing to illustrate teamwork behaviors.

Evaluation

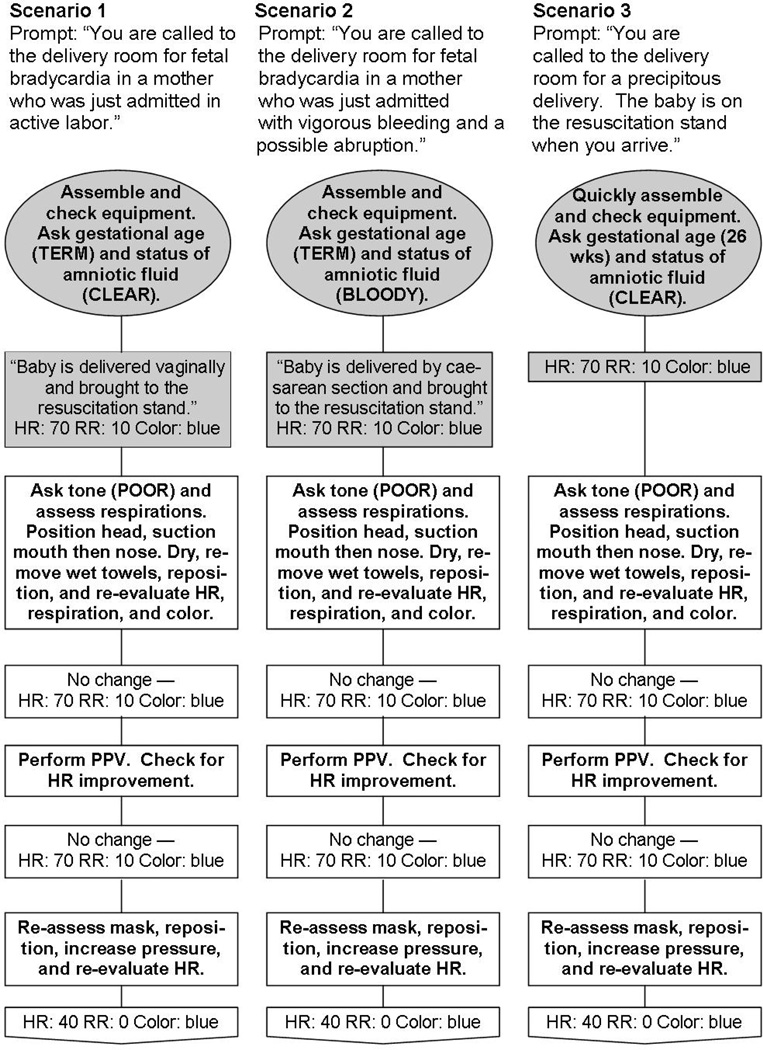

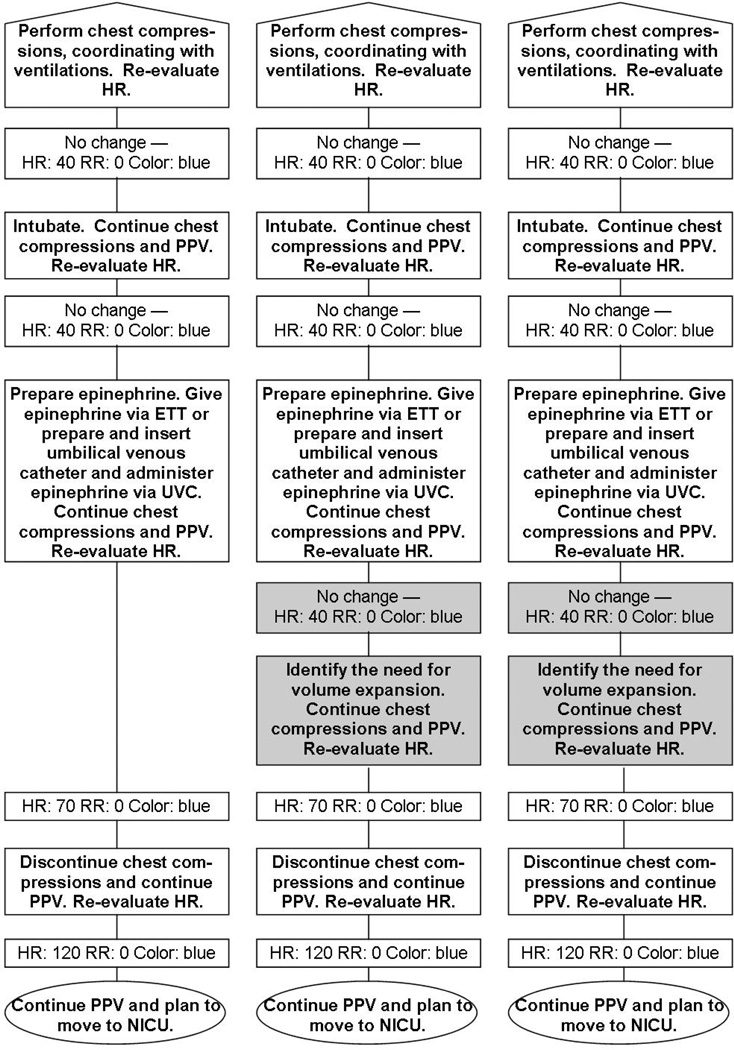

At the end of the NRP certification process, all participants (in their assigned teams) were evaluated by megacode resuscitation scenarios. All of the teams were given a brief introduction to the simulator before the scenario and each participant led a resuscitation scenario, while being assisted by their team members. Three standardized scenarios were developed for the study (see Appendix) and they differed in two key components. One scenario was a precipitous delivery and therefore the team was not given time to prepare their equipment before the infant was born and the two of the scenarios required the additional step of volume administration during the resuscitation. These scenarios were video recorded and edited to begin when the instructor started the scenario prompt and end immediately after the team indicated that the infant was ready to be transferred to the NICU.

Interns from pediatrics and combined medicine-pediatrics specialties (n=43) were eligible for a follow-up evaluation six months after initial NRP certification. These follow-up evaluations were randomly mixed into the dataset so that study personnel evaluating the scenarios were blinded to baseline and follow-up status.

Data collection

Megacode resuscitation scenarios were video-recorded and evaluated by four independent research nurses who were blinded to the team’s intervention status. Occurrence of teamwork behaviors and overall team performance was assessed using Noldus Observer XT (version 7.0, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands).

Seven specific teamwork behaviors, emphasized during the team training intervention, were analyzed by the research nurses via the video recordings. These included behaviors of sharing information, inquiry, assertion, teaching/advising, evaluation of plans, vigilance, and workload management. Definitions and examples of each behavior are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of teamwork behaviors emphasized during the team training intervention.

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sharing Information (Event) |

Verbalization of information directed to the other team members that relates to the assessment of the baby. Examples: Verbalization of heart rate, color, tone, vocal cord visualization, statements of opinion, advocating of views in NON-critical moments, and other relevant observations or impressions about the baby’s status. |

| Inquiry (Event) |

Providers asked questions of each other. The questions related to anything about the resuscitation. |

| Assertion (Event) |

An individual provider asserted an opinion relating to the resuscitation procedure during a CRITICAL time. This behavior often related to a change of phase in the resuscitation (e.g. “We need to intubate this baby.”) Assertion may have been indirect, through the use of repeated questions (e.g. “Do you really think the ET tube is in the esophagus?”). Assertion did not include: 1) routine statements or questions about heart rate, tone, color, and respirations, or 2) descriptions of steps which were already occurring or statements concerning “continuing” what was already occurring. Assertion was not scored during the preparation portion of the simulation. |

| Teaching / Advising (Event) |

Either: 1) an exchange of information between any of the providers where the topic extended beyond the current resuscitation and conveyed information about other situations which were similar in some way, or 2) advice concerning another provider’s technique during the resuscitation. Teaching may have been short, informal information exchanges and did not have to convey correct information. |

| Evaluation of Plans (Event) |

An explicit DISCUSSION about the status of the baby and the decisions made to get to the current situation. This behavior included a detailed review of plans. Evaluation of plans included comments from multiple team members. Each team members’ contribution to the discussion was scored separately as “evaluation of plans”. Evaluation of plans was not scored during the preparation portion of the simulation. |

| Vigilance (State) |

Providers remained alert and focused on the resuscitation. Vigilance should be stopped when any of the team members looks away from the baby, equipment (including the wall clock), team, or instructors for at least 3 seconds during the resuscitation procedure. Vigilance was not assessed during the preparation portion of the simulation. |

| Workload Management (State) |

The workload is distributed among those present at the resuscitation, and tasks are appropriately prioritized. Workload management should be stopped if any team member does not offer to help when they are needed during the resuscitation. Observers must identify a step that a team member should be helping with before scoring loss of workload management. Workload management was not assessed during the preparation portion of the simulation. |

Two teamwork observers received training in teamwork behavior assessment for approximately 50 hours each. Ten videos, randomly distributed throughout the data sets, were scored by both observers to assess interrater reliability. Teamwork observers coded the specific behaviors each time they occurred during the resuscitations. Five behaviors were scored as discrete verbalizations (sharing information, inquiry, assertion, teaching/advising, and evaluation of plans). Vigilance and workload management were scored as state behaviors, with a start and end time for each occurrence of the behavior (Table 1).

Two additional research nurses served as performance observers and were also blinded to participant team training status. Their training consisted of approximately 40 hours each during the 6-month training period. Twenty videos were randomly distributed throughout both observers’ data sets to evaluate interrater reliability. Performance observers scored each NRP step every time the step occurred during the resuscitation. Some steps occurred only once per resuscitation, but some steps, such as providing positive pressure ventilation, occurred multiple times within a resuscitation. Scores were assigned according to NRP Megacode Assessment Form (Advanced)6, in which a score of 0 is given when a step is omitted; 1 when the step is performed incorrectly, incompletely, or out of order; and 2 when the step is correctly performed.

Outcome measures

Resuscitation duration and performance scores are the outcome measures used to evaluate the quality of simulated resuscitations. Resuscitation duration was determined by calculating the total time required to complete a megacode scenario, from the start of the instructor’s reading of the scenario to the point at which a team declares the intent to transfer its patient to the NICU. When any teaching moments occurred during the simulation, the total teaching time was subtracted from the resuscitation duration. Performance score was calculated by averaging the scores (ranging from 0 to 2) for each step of the scenario. Those scores were summed and divided by the total possible score. This produced a measure of performance percentage, ranging from 0–100 % per scenario.

Analysis

Power calculations for the previous primary analyses5 were determined based on expected rates of teamwork behaviors during resuscitation scenarios, calculated from pilot data. Given two classes of interns (2007 – 2008) and an expected total of 102 participants, the trial was estimated to have 99.99% power to detect differences in teamwork rates between the three original study groups (control group, intervention group with high-fidelity, and intervention group with low-fidelity).

In this secondary analysis, two linear regression models were developed, one for resuscitation duration and one for performance score. Separate models were used for these outcomes as they were noted to be distinct indicators of resuscitation quality in our dataset. A linear regression analysis of the association between resuscitation duration and performance score yielded a coefficient of −0.08 (p=0.970).

Univariate analysis was conducted to evaluate the associations between independent variables (team training, teamwork behaviors, environment, and individual characteristics) and the dependent variables (resuscitation duration and performance score). The independent variables considered as potential predictors of duration and performance are divided into 4 categories and listed in Table 2. Variables were selected for multivariable regression model if there was a strong association in the univariate analyses (at α=0.2 level). A backward stepwise variable selection procedure was used for the multivariable models.

Table 2.

Variables considered in univariate analyses were divided into four categories.

| Mean or % Yes (n=132) |

Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Team Training: | ||

| Team training (Y/N) | 61% | - |

| High-fidelity skills stations (Y/N) | 31% | - |

| Teamwork behaviors: | ||

| Sharing information (behaviors/min) | 5.6 | 2.7, 11.2 |

| Inquiry (behaviors/min) | 2.1 | 0.5, 5.2 |

| Assertion (behaviors/min) | 2.8 | 1.0, 7.0 |

| Teaching/advising (behaviors/min) | 0.2 | 0, 1.5 |

| Maintain vigilance (Y/N) | 86% | - |

| Maintain workload management (Y/N) | 74% | - |

| Environment: | ||

| Instructor hints (events/min) | 0.2 | 0, 1.5 |

| Instructor teaching time (sec) | 20 | 0, 316 |

| Crisis scenario (Y/N) | 31% | - |

| Follow-up megacode (Y/N) | 26% | - |

| Individual characteristics: | ||

| Pediatrics resident (Y/N) | 48% | - |

| Internal medicine/pediatrics resident (Y/N) | 10% | - |

| OB-GYN resident (Y/N) | 10% | - |

| Emergency medicine resident (Y/N) | 16% | - |

| Family medicine resident (Y/N) | 16% | - |

The primary independent variables of interest were team behaviors and team training status. Environmental and individual characteristics were included in the models as confounders for which adjustment was necessary. In addition, team training seemed to have a different effect on performance and duration, depending the type of scenario (particularly, the shorter “crisis scenarios”). Therefore, an interaction was assessed for the team training status x crisis scenario in both models, but the interaction was not statistically significant in either model. Continuous variables were further evaluated to check the assumption of linearity in the model, and none were found to substantially violate linearity.

For timed events (resuscitation duration), log-transform analysis of resuscitation duration was performed and the same team behaviors and confounders were found to be significant in that model (results not presented). While the log-transformed durations were the more normally distributed than raw durations, only the raw duration model is reported here to facilitate clearer interpretation of the coefficients.

For the purpose of this analysis, evaluations of all resuscitation scenarios (baseline and follow-up) were included. The models were duplicated on data from baseline resuscitations only, and similar results were obtained, so those results are not reported. All analyses included adjustments for repeated measures correlations between baseline and follow-up resuscitations led by the same individual using clustered sandwich variance estimators. Statistical significance was assessed at α=0.10 for variables included in the final models because this was an exploratory study with potentially limited power to detect associations between teamwork and performance measures7. STATA/IC version 10.1 was used to perform these analyses.

The University of Texas Health Science Center Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved all study procedures.

RESULTS

From 121 eligible trainees, 100 consented to study participation and were randomized to one of three groups: 1) standard NRP training (n=36), 2) team training and NRP with low-fidelity skills stations (n=31), or 3) team training with high-fidelity skills stations (n=33). Two participants from group 3 were unable to complete the resuscitation scenarios. 39 of 43 eligible participants returned for the 6 month follow-up evaluations. Five of the follow-up video-recordings could not be analyzed due to technical difficulty. Therefore, a total of 132 resuscitation scenarios (98 baseline and 34 follow-up) were analyzed for the purpose of this study.

Resuscitation duration

The mean resuscitation duration was noted to be 533 sec (Range: 162 – 1536 sec) in the original study. In univariate analysis, team training participation, use of specific teamwork behaviors (assertion and sharing information), environment (practice with high-fidelity simulation and type of resuscitation scenario), and certain individual characteristics (type of subspecialty) were significantly associated with resuscitation duration. In multivariate analysis, only three of these factors remained significant: 1) participation in team training; 2) use of team behaviors of assertion and sharing information; and 3) participation in crisis type of scenario (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing resuscitation duration.

| Variable | Coefficient a | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team training participation | −94 | −163.8, −24.5 | 0.009 |

| Team behavior - assertion(behaviors/min) | −40 | −71.5, −10.2 | 0.010 |

| Team behavior - sharing information (behaviors/min) | −13 | −30.4, 2.9 | 0.104 |

| Scenario type – crisis scenario | −94 | −155.2, −34.1 | 0.003 |

| Constant | 813 | 691.6, 934.3 | <0.0005 |

Coefficients represent the change in duration (in seconds) associated with either the presence of the factor (for team training and scenario type) or a one unit increase in the level of the covariate (for assertion and sharing information).

Analysis of the resuscitation duration model with only team training participation as the independent variable suggests that on average, intervention teams (those who received team training) completed scenarios 127 seconds faster than the control group (P=0.001). After adding independent variables of teamwork behaviors and type of scenario to the model, the team training effect on resuscitation duration is reduced, but remains significant with a reduction in resuscitation duration of 94 sec (P=0.009, table 3).

Resuscitation performance

The average performance score was noted to be 71.6% per scenario (range: 50–87%) in the original study. In univariate analysis, performance score was associated with: 1) use of team behaviors of assertion and sharing information; 2) participation in crisis type of scenario; 3) timing of assessment (follow-up), and 4) type of subspecialty (specifically, emergency medicine). In multivariate analysis, all of these variables from univariate analysis remained significantly associated with resuscitation performance score (table 4). The frequency of sharing information and assertion behaviors were associated with increased performance scores even after adjusting for scenario type, timing of assessment, and subspecialty of participants (table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate model of factors influencing NRP performance score.

| Variable | Coefficient a | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team behavior - assertion (behaviors/min) | 1.60 | 0.4, 2.7 | 0.007 |

| Team behavior - sharing information (behaviors/min) | 0.77 | 0.05, 1.5 | 0.036 |

| Scenario type- crisis scenario | −2.93 | −5.6, −0.26 | 0.032 |

| Timing of assessment – 6 month follow-up | −2.17 | −4.7, 0.37 | 0.094 |

| Type of residency program - emergency medicine | 5.39 | 2.0, 8.8 | 0.002 |

| Constant | 63.31 | 58.6, 68.1 | <0.0005 |

Coefficients represent the change in performance score percentage associated with either the presence of the factor for crisis scenario and emergency medicine specialty, or a one unit increase in the level of the covariate for assertion rate and sharing information rate.

DISCUSSION

Teaching teamwork behaviors necessary to perform efficiently in a high stress environment is one strategy for improving resuscitation training. Secondary analysis of a randomized trial of interns undergoing NRP certification indicates that assertion and sharing information were most important for reducing resuscitation duration and improving performance.

Teamwork behaviors

Assertion is a team behavior that allows an individual to assert an opinion or speak up during a critical time. For example, a team member may state “let’s do chest compressions,” or “We need to intubate.” This communication cues the team to initiate a new phase and changes the course of the resuscitation. A high rate of assertion type behaviors could facilitate rapid progression through the phases of resuscitation, from bag-mask ventilation to intubation to chest compressions. In our cohort, each additional use of assertion type behavior (per minute) is associated with 41 sec decrease in resuscitation duration and 1.6% increase in the performance score (P=0.009 and P=0.007 respectively).

Sharing information is a behavior that involves verbalization of information relating to the assessment of the baby, such as verbalizing heart rate after evaluating the pulse, and presence of breath sounds after auscultation. When a team member communicates “the baby is not breathing,” and “heart rate is 70,” this information drives the team to react to the assessments made. Since these initial steps of evaluation steer the course and direction of the resuscitation, communication of critical information to team members by “sharing information” appropriately can result in faster completion of the scenario and higher performance scores. In our analysis, each additional use of sharing information type behavior (per minute) was associated with a 14 sec decrease in the resuscitation duration and a 0.8% increase in the performance score (P=0.104 and 0.036 respectively). This is likely due to more efficient communication, leading to rapid assessment and intervention.

The association between team behaviors, resuscitation duration, and performance score noted in our study is plausible. Many of the performance indicators measured (via NRP Assessment form) are based on a teams’ ability to identify the need for specific interventions. These include appropriately identifying the need for positive-pressure ventilation, chest compressions, intubation, and medications during the resuscitation of a newborn. Therefore, participants who were most comfortable asserting their opinions to their teams could progress through the resuscitation faster. In a similar manner, effectively verbalizing their findings, by sharing information, allowed teams to make rapid assessments and respond more efficiently and appropriately, leading to shorter duration and higher performance scores. Published reports from disciplines within and outside of medicine have noted a similar association between team behaviors of assertion, sharing information and team performance 8–12. A meta-analysis of 72 independent studies that were conducted in varying contexts of medicine, industry, and business has noted that information sharing is a “clear driver” and positive predictor of team performance8. While many highlight the importance of sharing information8 in determining a team’s performance, the lack of or inconsistent use of these behavioral skills has been noted during critical events, especially in interdisciplinary environments, where effective team performance is dependent on “transfer of critical information”9. Teamwork behaviors such as assertion have been shown to play an important role in improving communication, reducing errors, and improving teamwork by allowing team members to speak up and advocate for patients during critical times in the operating room11,12.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several methodological strengths, including the benefits of randomization for the purpose of studying an educational intervention and the great measures taken to reduce bias in the evaluation process. This form of detailed, quantitative assessments of individual behaviors and their relationship to resuscitation quality have not been measured previously in the context of teamwork during resuscitation training. Our study design (randomized controlled trial) has also been used very infrequently for studying interventions related to trainees. We are one of first to study effects of team training in a controlled fashion and identify specific behaviors that are predictive of quality measures related to resuscitation. Furthermore, our study includes trainees from varying training and educational backgrounds, belonging to various subspecialties. This diversity among study participants is helpful for generalizing the results of our study and consideration of potential benefits of team training in areas of pediatric and adult resuscitation training.

There are certain limitations to our study. While we identified several important mediating factors that are associated with resuscitation efficiency, we were not able to identify all of the mediators through which team training improves resuscitations. Participation in team training reduced the resuscitation duration by 2.1 minutes (P=0.001). After adjusting for team behaviors and type of scenario, the reduction in resuscitation duration is 1.6 minutes (P=0.009). Therefore, the variability in resuscitation duration due to the team training intervention cannot be fully explained by differences in teamwork behaviors alone. This may be due to unmeasured factors and variability in baseline experience of participants in performing newborn resuscitations.

Furthermore, we noted that if the team was presented with a crisis situation where they are asked to attend a delivery without time for preparation, the resuscitation duration was significantly shortened (by 94 sec, P=0.003) and the performance score was significantly diminished (by 2.9%, P=0.032). This association between type of scenario and resuscitation duration and performance score is expected as the crisis type scenario was shorter in its design and did not require as many steps during resuscitation as the other scenarios. In addition, as the teams did not have the time to prepare for the delivery in advance and setup equipment, it is plausible that their performance during the scenario may be compromised as a result.

The significance of our results on clinical outcomes is uncertain. In particular, the influence of team behaviors on performance scores seems modest. However, the performance score improvements are associated with each additional teamwork behavior per minute, and increases in performance become more prominent as the behaviors are used more frequently. It is uncertain whether these modest changes in the simulated environment translate into higher quality, trainee driven resuscitations in real clinical scenarios. However, previous studies reassure us that mastery of skills in the simulated environment can influence educational outcomes13–15.

Implications

The findings of our study may help refine efforts to provide team training during resuscitation training programs, such as the NRP, Pediatric Advanced Life Support, Basic Life Support, and Advance Cardiac Life Support certifications. Teaching teamwork behaviors, alongside with technical skills, is a potential strategy for improving educational outcomes for residents and clinical outcomes for patients. In particular, training might be improved by specific focus on behaviors such as assertion and sharing information. However, it is essential to study the role of these teamwork behaviors in real-world, newborn, pediatric, and adult resuscitations.

CONCLUSION

Teamwork behaviors such as assertion and sharing information are some of the important mediators through which team training improves efficiency and performance of a team during simulated resuscitations. Further study of team training is required to identify other potential behavioral factors that may be responsible for mediating the influence of team training on efficiency and quality of resuscitations.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

This study was supported by a grant from the dean’s office of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston and National Institutes of Health grant UL1 RR024148 (CTSA) and Dr. Eric Thomas’ grant - Improving the Safety and Quality of Pediatric Health Care (1K24HD053771-01), from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Appendix A: Scenarios for simulated resuscitations. Team actions are in bold.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halamek LP. Educational Perspectives: The Genesis, Adaptation, and Evolution of the Neonatal Resuscitation Program. Neoreviews. 2008;9:e142–e149. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effective team leadership improves neonatal resuscitation. NRP Instructor Update. 2004;13(2) ed, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstock P, Halamek LP. Teamwork during resuscitation. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2008.04.001. xi–xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Joint Commission. Preventing infant death and injury during delivery. Sentinel Event Alert. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas EJ, Williams AL, Reichman EF, et al. Team training in the neonatal resuscitation program for interns: teamwork and quality of resuscitations. Pediatrics. 2010;125:539–546. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kattwinkel J. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation. American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilhelmus KR. Beyond the P: III: Possible insignificance of the nonsignificant P value. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:2425–2426. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesmer-Magnus JR, Dechurch LA. Information sharing and team performance: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:535–546. doi: 10.1037/a0013773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller K, Riley W, Davis S. Identifying key nursing and team behaviours to achieve high reliability. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17:247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley P, Cooper S, Duncan F. A mixed-methods study of interprofessional learning of resuscitation skills. Med Educ. 2009;43:912–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke JR, Johnston J, Blanco M, et al. Wrong-site surgery: can we prevent it? Adv Surg. 2008;42:13–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pian-Smith MC, Simon R, Minehart RD, et al. Teaching residents the two-challenge rule: a simulation-based approach to improve education and patient safety. Simul Healthc. 2009;4:84–91. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31818cffd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halamek LP. The simulated delivery-room environment as the future modality for acquiring and maintaining skills in fetal and neonatal resuscitation. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halamek LP, Kaegi DM, Gaba DM, et al. Time for a new paradigm in pediatric medical education: teaching neonatal resuscitation in a simulated delivery room environment. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E45. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan CA, Clark LM, Malone A, et al. The effect of a structured neonatal resuscitation program on delivery room practices. Neonatal Netw. 1999;18:25–30. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.18.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]