This article reports the isolation and phenotypic characterization of a temperature-sensitive allele of the Microprocessor component PASH-1 (known as DGCR8 in mammals) in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. This allows rapid and reversible inactivation of miRNA production in vivo. Interestingly, a shift of pash-1 mutant adults to restrictive temperature results in reduced lifespan, which can be rescued by tissue-specific expression of pash-1 in neurons, hypodermis, and muscle. The effect of miRNAs on lifespan is not acting through the insuling signaling pathway. Their results strongly suggest a post-developmental role for miRNAs in C. elegans affecting lifespan.

Keywords: PASH-1, DGCR8, miRNA, physiology, C. elegans

Abstract

Regulation of gene expression by microRNAs (miRNAs) is essential for normal development, but the roles of miRNAs in the physiology of adult animals are poorly understood. We have isolated a conditional allele of DGCR8/pash-1, which allows reversible and rapid inactivation of miRNA synthesis in vivo in Caenorhabditis elegans. This is a powerful new tool that allows dissection of post-developmental miRNA functions. We demonstrate that continuous synthesis of miRNAs is dispensable for cellular viability but critical for the physiology of adult animals. Loss of miRNA synthesis in the adult reduces lifespan and results in rapid aging. The insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway is a critical determinant of lifespan, and is modulated by miRNAs. We find that although miRNA expression is required for some mechanisms of lifespan extension, it is not essential for the longevity of animals lacking insulin/IGF-1 signaling. Further, misregulated insulin/IGF-1 signaling cannot account for the reduced lifespan caused by disruption of miRNA synthesis. We show that miRNAs act in parallel with insulin/IGF-1 signaling to regulate a shared set of downstream genes important for physiological processes that determine lifespan. We conclude that coordinated transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression promotes longevity.

INTRODUCTION

microRNAs (miRNAs) are a widespread class of noncoding ∼22 nucleotide (nt) endogenous RNAs found in animals, plants, and algae (Bartel 2009). These RNAs inhibit gene expression by blocking translation and/or destabilizing target mRNAs. The first miRNAs, lin-4 and let-7, were identified as regulators of developmental timing in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Lee et al. 1993; Wightman et al. 1993; Reinhart et al. 2000). Since then, the repertoire of animal miRNAs has greatly expanded to hundreds of miRNAs in many species. Comparative genomics suggests that more than half of animal mRNAs are directly subject to miRNA regulation (Friedman et al. 2008). A number of approaches, including reverse and forward genetics, have identified functions for miRNAs in animal and plant development, homeostasis, and disease (Bushati and Cohen 2007).

C. elegans is an important model organism for aging research, and a number of genetic pathways that determine longevity in this organism are known. Many of these pathways are linked to metabolism and stress responses and have conserved roles in other animals, including humans (Kenyon 2010). Mutations that affect these pathways can reduce, or remarkably, increase lifespan. The insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway is an important regulator of aging. This role was first identified in C. elegans, but is also conserved in other animals (Tatar 2003). daf-2 encodes the sole Insulin/IGF-1 receptor in C. elegans, and mutations that inactivate DAF-2 extend lifespan (Kenyon et al. 1993). The extended lifespan of IIS-defective mutants is mediated by downstream transcription factors. One of these, the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16 is essential for the extended lifespan of daf-2 mutants (Ogg et al. 1997). In wild-type C. elegans cultured under conditions favorable for growth and reproduction, DAF-16 is inhibited by IIS-dependent phosphorylation, which prevents its nuclear localization (Lin et al. 2001). When IIS is absent, DAF-16 is constitutively localized to the nucleus, where it changes expression of a diverse set of downstream genes that determine lifespan (Lee et al. 2003; McElwee et al. 2003; Murphy et al. 2003).

DAF-16 is one of a number of transcription factors that are key components of the genetic pathways controlling aging in C. elegans (Ogg et al. 1997; Hsu et al. 2003; Fisher and Lithgow 2006; Panowski et al. 2007; Shaw et al. 2007; Tullet et al. 2008). These transcription factors control expression of genes with functions relevant to metabolism, cellular maintenance, and repair, which in turn determine longevity. Whether post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs could have a similar role is not known. Many miRNAs show dynamic changes in expression during aging in C. elegans, and some miRNAs are predicted to target genes implicated in aging (Ibáñez-Ventoso et al. 2006; de Lencastre et al. 2010). Also, some miRNAs have been linked to aging, via modulation of IIS and DAF-16. The lin-4 miRNA controls temporal cell fates during larval development (Lee et al. 1993; Wightman et al. 1993) and regulates aging via its target LIN-14 (Boehm and Slack 2005). Since inactivation of LIN-14 in adult animals is sufficient to extend lifespan, lin-4 is thought to act post-developmentally to regulate aging. The extended lifespan of lin-14 mutants requires DAF-16, suggesting that lin-4 regulates lifespan via IIS. Additional miRNAs have been implicated as both positive and negative regulators of lifespan; however, it has not been determined if these miRNAs act during development or in the adult. mir-71 mutants have a reduced lifespan, and miR-71 is required for the extended lifespan of daf-2 mutants (de Lencastre et al. 2010). Mutants lacking mir-239 have a longer lifespan than the wild type, and this lifespan extension requires daf-16, so different miRNAs may modulate lifespan through antagonistic effects on IIS/DAF-16 (de Lencastre et al. 2010).

Although it is clear that miRNAs can influence lifespan, the extent to which miRNAs contribute to normal physiology of adult animals is not clear. Using only knockout alleles, it is not possible to dissect indirect developmental effects from genuine cases of abnormal physiology. miRBase lists 368 miRNAs in C. elegans (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones 2010), so individually examining each miRNA mutant can be prohibitively time-consuming. Even then, such an analysis would not be exhaustive, as some miRNA mutants have severe developmental defects that prevent analysis of their physiology. Further, a knockout-based approach would not identify cases where multiple miRNAs act redundantly. Using knockout alleles of essential miRNA biogenesis factors is difficult, as these mutants are not viable.

Here we describe a conditional allele of the miRNA pathway gene DGCR8/pash-1, which allows reversible and rapid inactivation of miRNA synthesis. This mutant is a powerful new tool for investigating the biological functions of microRNAs in C. elegans. Using this mutant it is possible to rapidly assess the physiological functions of miRNAs by examining animals that cannot synthesize miRNAs, and allow dissection of physiological functions from development, by inactivating miRNA synthesis specifically in adult animals. We use this mutant to demonstrate that post-developmental expression of miRNAs is essential for normal physiology and lifespan.

RESULTS

Temperature-sensitive miRNA biogenesis in pash-1ts mutants

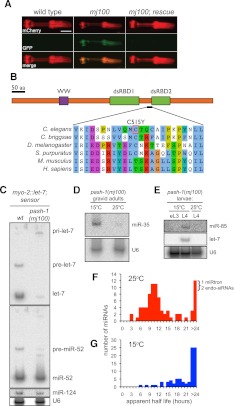

We previously described a sensitive in vivo assay for miRNA function based on a pharyngeal GFP reporter that is silenced by ectopic expression of let-7 (the miRNA sensor) (Lehrbach et al. 2009). In a genetic screen using the miRNA sensor, we isolated a temperature-sensitive lethal mutant defective in miRNA sensor silencing (Fig. 1A). At 15°C, mutant animals develop normally despite deregulation of the miRNA sensor, but animals are not viable at 25°C. In mapping experiments, failure to silence the miRNA sensor and lethality at 25°C were tightly linked (data not shown), suggesting a single allele (mj100) underlies both defects. We mapped the mutation to a 200-kb interval on chromosome I and identified a missense mutation in the pash-1 gene (Supplemental Fig. S1). pash-1 encodes the C. elegans ortholog of DGCR8/Pasha, which is required for the first step of miRNA biogenesis (Denli et al. 2004; Gregory et al. 2004). The mutation results in substitution of tyrosine for cysteine at amino acid 515, a partially conserved residue within the dsRNA-binding domain of PASH-1 (Fig. 1B). Transformation with the wild-type pash-1 gene, or a transgene driving ubiquitous expression of a PASH-1-GFP fusion protein, restored miRNA sensor silencing, and viability at 25°C (Fig. 1A; data not shown). We conclude that mj100 is a loss-of-function allele of the pash-1 gene that results in temperature-sensitive lethality. We hereafter refer to pash-1(mj100) as pash-1ts.

FIGURE 1.

mj100 is a temperature-sensitive allele of pash-1. (A) Fluorescence micrographs showing defective let-7–mediated silencing of a reporter transgene expressed in the pharynx. This defect is rescued by a fosmid covering the pash-1 locus. All animals are young adults raised at 20°C. (B) Domain structure of PASH-1 showing the sequence alteration resulting from the pash-1(mj100) mutation. (C) Northern blot comparing miRNA expression in otherwise wild-type and pash-1(mj100) animals carrying the myo-2∷let-7 transgene, grown at 20°C. pash-1(mj100) mutants show drastically reduced expression of let-7 from the myo-2∷let-7 transgene, but levels of endogenous miRNAs are similar to that of the wild type. (D) Northern blot showing temperature-sensitive synthesis of miR-35 in pash-1(mj100) mutants. Animals were shifted to 25°C during L4. (E) Northern blot showing temperature-sensitive synthesis of miR-85 and let-7 in pash-1(mj100) mutants. Animals were shifted to 25°C during early L3 (eL3). (F,G) Histograms comparing apparent miRNA half-life after upshift of pash-1(mj100) animals to 25°C and in control animals maintained at 15°C.

As viability of pash-1ts mutants depends on temperature, the pri-miRNA processing activity of the PASH-1(C515Y) mutant protein might be temperature-sensitive. While pash-1ts strains containing the myo-2∷let-7 transgene are viable at 20°C, these animals show drastically reduced levels of both pre-let-7 and let-7, and accumulation of a larger RNA, presumably the let-7 pri-miRNA (Fig. 1C). This is consistent with the known role of PASH-1 in pri-miRNA processing, and the failure of pash-1ts mutants to silence the miRNA sensor. Although miRNA biogenesis is partially defective, endogenous miRNAs are expressed at or near wild-type levels, consistent with the viability of the pash-1ts mutant at 20°C.

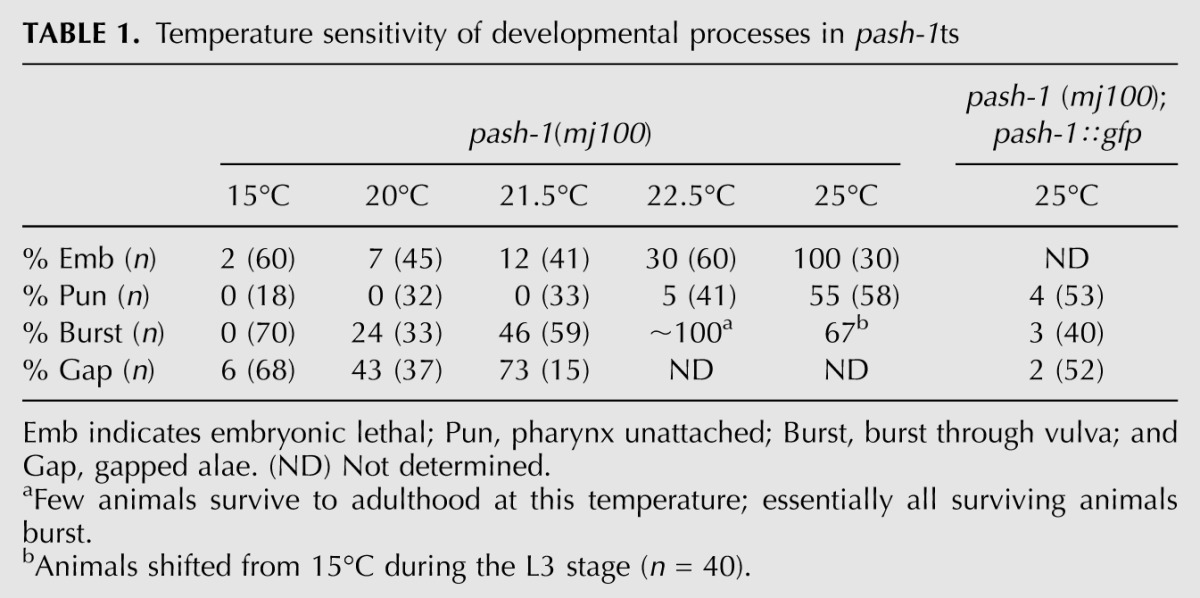

Next we measured miRNA expression at 25°C, at which pash-1ts mutants are not viable. To do this, we chose miRNAs with specific temporal expression patterns. miR-35 is expressed specifically during embryogenesis (Martinez et al. 2008a; Alvarez-Saavedra and Horvitz 2010). miR-35 is present in total RNA from pash-1ts gravid adult animals (which contain embryos) raised at 15°C. miR-35 is absent in pash-1ts animals raised at 15°C until the final larval stage (L4) and then shifted to 25°C (Fig. 1D). This is not due to a failure of pash-1ts animals to produce embryos after upshift to 25°C (data not shown). Rather, at 25°C pash-1ts embryos are unable to synthesize mature miR-35. We obtained similar results with miR-85 and let-7, which are expressed from the third larval stage (L3) onward (Fig. 1E; Reinhart et al. 2000; Martinez et al. 2008b). We also examined the temperature sensitivity of development of pash-1ts mutants, testing for defects known to arise in specific miRNA mutants (Table 1). At 15°C, these defects are either absent or rare. In contrast, at 25°C pash-1ts mutants show a number of severe defects, including 100% embryonic lethality, which are rescued by pash-1∷gfp. These data indicate that at 15°C PASH-1(C515Y) has sufficient activity for miRNA expression and normal development. However, at 25°C the activity of PASH-1(C515Y) is drastically reduced, such that pash-1ts animals lack appreciable miRNA expression at this temperature. Inactivation of miRNA synthesis in pash-1ts at 25°C appears to be rapid, as upshift a few hours prior to the onset of let-7 and miR-85 expression prevents expression of these miRNAs. We will refer to 15°C as the permissive temperature, and 25°C as the restrictive temperature.

TABLE 1.

Temperature sensitivity of developmental processes in pash-1ts

miRNAs have a range of half-lives in vivo

miRNA expression levels depend on their rates of synthesis and decay (Chatterjee and Großhans 2009; Krol et al. 2010), but in vivo rates of miRNA turnover are not known. The temperature-sensitive miRNA synthesis of pash-1ts mutants provides a means to reveal miRNA turnover rates, by measuring the rate at which mature miRNAs are cleared after inactivation of miRNA synthesis. We measured miRNA levels by microarray in a time-course over 34 h after pash-1ts animals raised at the permissive temperature were shifted to the restrictive temperature. As a control, a similar analysis was performed using animals that were kept at the permissive temperature for the whole experiment. Seventy-five miRNAs were detected by the array; most showed reduced expression at the restrictive, but not the permissive, temperature (Supplemental Data File 1). As measured by Northern blot, miRNA levels do not similarly drop after upshift of pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp animals, confirming that this results from the pash-1ts defect, not a general effect of temperature on miRNA levels (Supplemental Fig. S2). The array also detected one mirtron and two endogenous siRNAs, which did not show reduced expression at the restrictive temperature. We used these data to estimate the in vivo half-life of the RNAs detected. The half-life of most C. elegans miRNAs is ∼10 h at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 1F,G; Supplemental Data File 2). Notably, some miRNAs had a significantly shorter (mir-71; ∼3 h) or longer (miR-85; ∼28 h) half-life. Although it remains possible that some miRNAs' synthesis may be more rapidly inactivated after upshift than others, these data suggest miRNA-specific regulation of turnover and stability.

Ongoing miRNA synthesis in the adult is required for normal lifespan

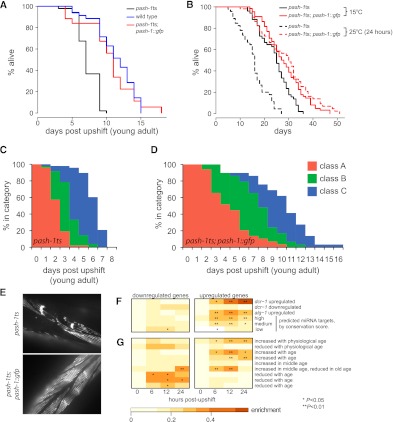

Since miRNA synthesis is rapidly lost upon upshift of pash-1ts animals to the restrictive temperature, this mutant is an ideal tool to investigate the physiological functions of miRNAs. Any defects observed in pash-1ts adults placed at the restrictive temperature must reflect physiological processes that require continuous miRNA expression. We tested the effect of disrupting miRNA synthesis during adulthood on lifespan. The mean lifespan of pash-1ts adults shifted to the restrictive temperature is significantly shorter than that of similarly temperature-shifted wild-type animals (mean lifespan reduced by 31%, P = 2 × 10−11 log rank test) (Fig. 2A). This defect is rescued by pash-1∷gfp, confirming that it results from the pash-1ts lesion. As miRNA synthesis is mildly impaired in pash-1ts even at the permissive temperature, the reduced lifespan of pash-1ts at the restrictive temperature could in theory be explained by a requirement for efficient miRNA synthesis during development. To test this we compared the lifespan of pash-1ts and pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp animals kept at the permissive temperature (15°C). At 15°C, the mean lifespan of pash-1ts animals is reduced by 13% compared with the rescued animals (P = 0.002 log rank test) (Fig. 2B). Reduced lifespan at the permissive temperature suggests that lifespan is very sensitive to miRNA expression levels. However, a greater reduction in lifespan is observed after upshift of adult animals to the restrictive temperature (31% vs. 13% reduction in mean lifespan). So miRNAs synthesized post-developmentally must have functions that affect lifespan.

FIGURE 2.

Continuous miRNA synthesis in adults is required for normal aging. (A) The lifespan of pash-1ts adult animals placed at the restrictive temperature is reduced compared with that of wild-type or pash-1ts animals carrying a ubiquitously expressed pash-1∷gfp transgene (31% reduction in mean lifespan, P < 1 × 10−5, log rank test). (B) When grown entirely at 15°C, the lifespan of pash-1ts animals is slightly shorter than pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp (13% reduction in mean lifespan, P = 0.002, log rank test). The lifespan of pash-1ts animals is reduced by a 24 h upshift to 25°C at the young adult stage (36% reduction in mean lifespan, P < 1 × 10−10, log rank test). The lifespan of pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp is not similarly affected (P = 0.3). (C,D) Rapid age-related decline in locomotion in pash-1ts adult animals placed at the restrictive temperature, compared with rescued pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp animals. Class A, vigorous sinusoidal locomotion; Class B, sluggish nonsinusoidal locomotion; and Class C, effectively paralyzed animals that twitch or move only very slightly in response to prodding. (E) Muscle degeneration in pash-1ts adults placed at the restrictive temperature. Fluorescence micrographs show MYO-3∷GFP expressing muscle cells, in animals 2 d after upshift to 25°C. (F) Genes up-regulated in pash-1ts adults placed at the restrictive temperature are enriched for genes up-regulated in other miRNA pathway mutants, and are enriched for genes with conserved miRNA target sites, as predicted by TargetScan. (G) Genes misregulated in pash-1ts adults placed at the restrictive temperature are enriched for genes that are differentially expressed during normal aging.

Next we asked whether continuous miRNA synthesis during adulthood is important for a normal lifespan. Inactivation of miRNA synthesis in pash-1ts mutants at the restrictive temperature is reversible through temperature downshift (data not shown). We therefore tested whether placing pash-1ts adults at the restrictive temperature for a short period would affect subsequent survival at the permissive temperature. Inactivation of miRNA synthesis for only 24 h in young adults reduces the lifespan of pash-1ts animals compared with those kept at the permissive temperature (P = 7 × 10−11, log rank test). This was not simply an effect of the change in temperature, as pash-1∷gfp rescued animals are not similarly affected (P = 0.3, log rank test) (Fig. 2B). This result indicates that major physiological changes that affect subsequent lifespan must occur within 24 h of inactivation of miRNA synthesis in young adult animals. Thus, continuous miRNA synthesis, at least during the first day of adulthood, is critical for normal physiology and longevity.

Animals unable to synthesize miRNAs age rapidly

While carrying out these lifespan assays, we noticed that locomotion declines rapidly in pash-1ts adults shifted to the restrictive temperature (Fig. 2C). Locomotion also declines in aging rescued animals, but at a much slower rate (Fig. 2D). Decline in locomotion is a marker of physiological age (Herndon et al. 2002), so these data suggest animals unable to synthesize miRNAs age rapidly. These data also suggest reduced healthspan in the absence of miRNA synthesis, as locomotion is impaired for a greater proportion of the adult life of mutant animals compared with rescue. After 24 h at the restrictive temperature, we observed a ∼30% decline in activity in pash-1ts compared with rescued animals (Supplemental Fig. S3), indicating ongoing miRNA synthesis is acutely required to maintain normal levels of locomotion. We examined other phenotypic markers of physiological age and found that adult pash-1ts animals placed at the restrictive temperature frequently display defects associated with advanced age much earlier than rescued animals. These include muscle degeneration and appearance of vacuoles throughout the body (Fig. 2E; data not shown). Interestingly, despite these defects, pash-1ts animals do not show signs of neurodegeneration, which is thought not to occur during aging in C. elegans (Herndon et al. 2002; data not shown).

To understand the basis for the abnormal physiology and reduced lifespan of animals unable to synthesize miRNAs, we profiled gene expression in pash-1ts animals and control pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp rescued animals during a 24-h time course following an upshift to the restrictive temperature. As expected, very few (less than 20) genes are misregulated in pash-1ts mutants at the permissive temperature. However, hundreds of genes are rapidly misregulated upon upshift, indicating miRNA synthesis during adulthood is required to maintain normal gene expression (Supplemental Table S1). We compared our data to previous microarray studies of dcr-1 and alg-1 mutants (Welker et al. 2007; Zisoulis et al. 2010). DCR-1 is required for synthesis of miRNAs and some endogenous siRNAs, and ALG-1 is an Argonaute protein required for miRNA biogenesis and function (Grishok et al. 2001; Ketting et al. 2001). Genes up-regulated in pash-1ts at the restrictive temperature are enriched for those up-regulated in dcr-1 and alg-1 mutants (Fig. 2F). This confirms that failure to synthesize miRNAs in pash-1ts mutants underlies the gene misregulation we observed. Indeed, we found enrichment for miRNA target genes, as predicted by TargetScan (Lewis et al. 2005; Jan et al. 2011), in genes up-regulated in pash-1ts at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 2F). This enrichment is dependent on conservation; we observed the strongest enrichment for genes with highly conserved target sites, and very weak enrichment for those genes with the most poorly conserved sites. This suggests that abnormal gene expression and defects in physiology in pash-1ts animals placed at the restrictive temperature result from a failure to repress conserved miRNA targets.

We next compared genes misregulated in pash-1ts with genes differentially expressed in aged animals (Fig. 2G; Golden et al. 2008). Genes that are normally up-regulated in old animals are rapidly up-regulated in pash-1ts at the restrictive temperature. Conversely, genes normally down-regulated in old animals are rapidly repressed. A set of genes that are up-regulated, then down-regulated, over the first ∼15 d of normal aging (in a study performed at 20°C) are up-regulated, then down-regulated over the course of 24 h in pash-1ts at the restrictive temperature. These data suggest that the reduced lifespan and age-associated defects of adult animals unable to synthesize miRNAs result from accelerated aging.

miRNAs promote longevity by cell autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms

Next, to further probe the basis for the reduced lifespan of pash-1ts adult animals placed at the restrictive temperature, we performed a series of tissue-specific rescue experiments. In C. elegans miRNAs function in a cell autonomous manner, so we assume that tissue-specific rescue of PASH-1 expression results in tissue-specific rescue of miRNA expression and function (Zhang and Fire 2010). If continuous microRNA expression is simply required for cellular viability, rescue of all somatic cells would restore lifespan to wild type, but rescue of any subset of cells would not increase lifespan, as this would still be limited by the death of nonrescued cells. On the other hand, if miRNA expression is required for a longevity-promoting physiological function in a particular cell type, then rescue of a subset of cells could at least partially restore longevity.

We generated transgenes placing expression of PASH-1∷GFP under control of various tissue-specific promoters. For all transgenes, we confirmed the desired pattern of expression by inspecting GFP fluorescence (data not shown). Rescue constructs expressed in all tissues restore longevity to wild-type levels (Figs. 2A, 3A). Rescue constructs expressed in the hypodermis, pharyngeal muscle, or gut did not increase lifespan, while rescue constructs expressed in body wall muscle had a marginal effect (Fig. 3B–E). However, expression of PASH-1∷GFP specifically in neurons significantly increased lifespan (Fig. 3G). Although mean lifespan after neuronal rescue is similar to that of animals rescued in all tissues, maximum lifespan is shorter (13 rather than 16 d), suggesting that miRNA expression in other tissues also contributes to longevity. Indeed, a transgene expressed in both hypodermis and muscle is sufficient to increase lifespan, although to a reduced extent compared with neuronal rescue (Fig. 3F). Restoring miRNA expression to only a subset of tissues can increase lifespan, so miRNAs are not autonomously essential for cell survival in the adult animal. Rather, inactivation of miRNA synthesis must lead to defects in cellular function, which in turn cause reduced lifespan. miRNAs regulate gene expression cell autonomously, but tissue-specific rescue of pash-1 increases lifespan of the whole animal, so at least some of the cellular functions controlled by miRNAs influence lifespan via cell nonautonomous mechanisms. As such, in animals that lack miRNA synthesis disorganized cellular and organismal function could lead to rapid accumulation of physiological defects and to precocious appearance of the phenotypic signs of old age.

FIGURE 3.

miRNA synthesis determines lifespan via cell nonautonomous mechanisms. (A–G) Survival curves comparing rescue activity of transgenes expressing PASH-1-GFP from various tissue-specific promoters. Black indicates pash-1ts. Green and gold indicate pash-1ts animals bearing rescuing transgenes. In each case, two independently derived extrachromosomal array transgenes are tested, except gut rescue (D), for which a single copy integrated transgene was tested. For G, extrachromosomal arrays were generated containing hypodermis and muscle-specific expression constructs. (*) Significantly increased lifespan compared to pash-1ts (P < 0.01, log rank test).

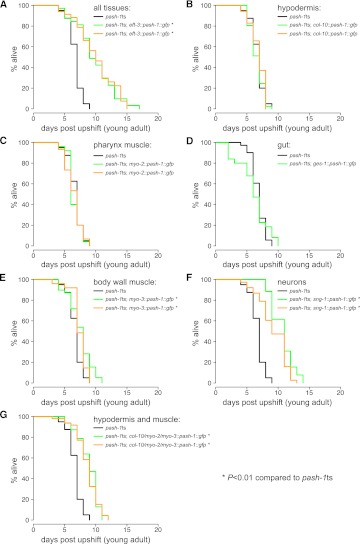

Ongoing miRNA synthesis is required for a subset of mechanisms of lifespan extension

Although some individual miRNAs are implicated in specific mechanisms of lifespan extension (Boehm and Slack 2005; de Lencastre et al. 2010; Boulias and Horvitz 2012), the role of miRNAs in other modes of lifespan extension is not known. Since the lin-4 miRNA regulates lifespan through regulation of LIN-14, we first tested whether failure to synthesize lin-4 could explain the reduced lifespan of pash-1ts animals at the restrictive temperature. The lin-4 miRNA promotes longevity by repressing LIN-14 expression; inactivation of lin-14 extends the lifespan and suppresses the reduced lifespan of lin-4 mutants (Boehm and Slack 2005). Inactivation of lin-14 in pash-1ts animals does not increase lifespan, although we confirmed that it extends lifespan in rescued animals (Fig. 4A). Therefore, failure to synthesize lin-4 cannot explain the reduced lifespan of pash-1ts animals at the restrictive temperature, and miRNAs are required for the mechanism by which lin-14 inactivation extends lifespan.

FIGURE 4.

Post-developmental miRNA synthesis is required for a subset of mechanisms of lifespan extension. (A–E) Survival curves comparing pash-1ts and pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp animals under conditions known to extend lifespan. Black lines indicate pash-1ts animals; red lines, pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp animals; solid lines, the control condition; and dashed lines, the lifespan extending condition. P-values (log rank test) are indicated for lifespan extension in pash-1ts and rescued backgrounds.

Next we tested whether various other modes of lifespan extension require miRNA synthesis (Figs. 4B–E, 5A). Since in each case details of the pathways that mediate lifespan extension are known, these experiments could indicate whether these pathways require miRNA synthesis to influence lifespan. Overexpression of JNK-1 extends lifespan in a daf-16–dependent fashion; JNK-1 directly phosphorylates DAF-16 (Oh et al. 2005). JNK-1 overexpression does not extend the lifespan of animals unable to synthesize miRNAs (Fig. 4B). The lifespan extension conferred by chronic caloric restriction (in eat-2 mutants) and the removal of germline stem cells (in glp-1 mutants) are largely dependent on miRNAs (Fig. 4C,D). In these cases, although the lifespan of pash-1ts animals can be extended at the restrictive temperature (P < 0.05, log rank test), the degree of extension is reduced compared with that of rescued animals. This suggests that lifespan extension occurs largely (but not entirely) via a miRNA-dependent mechanism, and implicates miRNAs in modulation of lifespan by these environmental and physiological cues. In addition, we found two cases where the degree of lifespan extension was not dependent on miRNA synthesis: reduction of mitochondrial function, and inactivation of the insulin receptor DAF-2 (Figs. 4E, 5A; Kenyon et al. 1993; Dillin et al. 2002).

FIGURE 5.

miRNAs and IIS independently regulate lifespan and metabolism. (A) Survival curves comparing lifespan extension by daf-2 loss of function in wild-type and pash-1ts animals. Blue indicates wild type; dashed blue, daf-2(e1370); black, pash-1ts; and dashed black, pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370). In wild-type animals, inactivation of DAF-2 increases mean lifespan by 146% (P < 0.01, log rank test). In pash-1ts animals, inactivation of DAF-2 increases mean lifespan by 121% (P < 0.01, log rank test). (B) Survival curves showing daf-16 dependence of lifespan, and lifespan extension by inactivation of daf-2 in pash-1ts animals. Black indicates pash-1ts; dark green, pash-1ts daf-16(mj283); dark green dashed, pash-1ts daf-16(mj283); daf-2(e1370); and red, pash-1(mj100) daf-16(mj283); pash-1∷gfp. Inactivation of DAF-2 in pash-1ts daf-16(mj283) double mutants does not extend lifespan (P = 0.5, log rank test). Mutation of daf-16 reduces the lifespan of pash-1ts mutants (12% reduction in mean lifespan, P = 7 × 10−5, log rank test). Inactivation of miRNA synthesis in daf-16(mj283) mutants reduces lifespan (26% reduction in mean lifespan, P = 4 × 10−8, log rank test). (C) PLS-DA plots comparing metabolite profiles of pash-1ts, pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp, daf-2(e1370), and pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) animals 24 h after upshift to the restrictive temperature. The metabolic changes that distinguish daf-2(e1370) from control animals are largely independent of miRNA expression. (D) Trehalose levels, as measured by NMR, are increased in both daf-2(e1370) and pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) 24 h after upshift. (E) Glycyl-proline levels, as measured by GC-MS, 24 h after upshift to the restrictive temperature. Glycyl-proline is present in daf-2(e1370), but not pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370), animals.

Inactivation of miRNA synthesis disrupts some, but not all mechanisms of lifespan extension. So, animals unable to synthesize miRNAs are not simply inviable but have physiological defects that can be partly suppressed when IIS or mitochondrial function is inhibited (Figs. 4E, 5A). Conditions that suppress the short lifespan of pash-1ts animals do not restore viability during development, so the requirements for miRNA synthesis for viability during development and adulthood are distinct. It was surprising that miRNA synthesis is not required for lifespan extension in the daf-2 Insulin/IGF-1 receptor mutant, as miRNAs have been implicated in the IIS pathway. We therefore decided to examine the relationship between miRNAs and IIS in more detail.

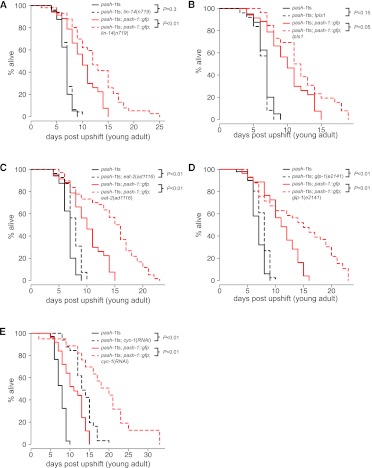

miRNA synthesis and IIS regulate aging by distinct mechanisms

Since pash-1ts and daf-2(e1370) are both temperature-sensitive alleles, we suppose that miRNA synthesis and IIS are inactivated coordinately in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants at 25°C. Simultaneous inactivation of both the DAF-2 insulin receptor and miRNA synthesis results in an extended lifespan (Fig. 5A). This effect is not due to increased miRNA levels or stability in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) animals compared with pash-1ts mutants, as measured by Northern blot (data not shown). Although the lifespan of pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants is shorter than that of daf-2(e1370) single mutants, the percentage increase in mean lifespan resulting from daf-2 inactivation is similar in the wild type (146%) and pash-1ts (121%). These data suggest that inhibiting IIS extends lifespan by a miRNA-independent mechanism and that miRNAs might promote longevity either upstream or in parallel to IIS.

Next, we constructed a pash-1ts daf-16(−) double mutant strain, by isolating a new daf-16–null allele in a daf-2 suppressor screen (mj283) (see Supplemental Methods; Supplemental Figs. S4, S5). As expected, the extended lifespan of pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants is entirely dependent on daf-16, so DAF-16 does not require ongoing miRNA synthesis to promote longevity, at least in daf-2(−) animals (Fig. 5B). At the restrictive temperature, the lifespan of pash-1ts daf-16(mj283) animals is 12% shorter than pash-1ts animals (P = 7 × 10−5, log rank test). Thus, DAF-16 also promotes longevity independent of miRNAs in daf-2(+) animals. Additionally, the lifespan of pash-1ts daf-16(mj283) animals is reduced compared with pash-1ts daf-16(mj283); pash-1∷gfp animals (P = 4 × 10−8, log rank test) (Fig. 5B). This indicates that adult miRNA expression must, at least in part, promote longevity by IIS and DAF-16–independent mechanisms.

Metabolic reorganization upon inactivation of DAF-2 occurs by miRNA synthesis dependent and independent mechanisms

Since both miRNAs and IIS are regulators of metabolism, we used metabolomic profiling to examine the phenotypic effects of coordinated inactivation of IIS and miRNA synthesis more closely. We profiled the metabolic state of pash-1ts, pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp, daf-2(e1370), and pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) 24 h after upshift to the restrictive temperature. Comparing the metabolic profiles of all four strains by partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), the metabolic changes that discriminate daf-2(e1370) animals from pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp animals (which are essentially wild type) are largely intact in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants (Fig. 5C). This suggests that inhibition of IIS alters many aspects of metabolism by miRNA-independent mechanisms. For example, daf-2 mutants produce large quantities of trehalose, a disaccharide associated with osmotic stress resistance in many invertebrates (Elbein et al. 2003). Up-regulation of trehalose synthase enzymes by DAF-16 is required for osmotic stress resistance of daf-2 mutants (Lamitina and Strange 2005). miRNA synthesis is dispensable for trehalose production in daf-2(e1370) animals (Fig. 5D), and miRNA synthesis is not required for the osmotic stress resistance of daf-2 mutants (Supplemental Fig. S6). However, some metabolic effects of inhibiting IIS are miRNA-dependent. At the restrictive temperature, glycyl-proline (GP) dipeptides accumulate in daf-2(e1370), but not pash-1ts; pash-1∷gfp control animals. This GP accumulation is lost in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants (Fig. 5E). GP arises from catabolism of GP-containing peptides, so this observation might indicate a miRNA-dependent effect on a protein turnover pathway. We conclude that, with a small number of exceptions, inhibiting IIS alters metabolism via miRNA-independent mechanisms. These data are consistent with the remarkable longevity of pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants; we conclude that miRNA synthesis is largely dispensable for the physiological changes that promote longevity of mutants lacking IIS.

Adult miRNA synthesis does not regulate lifespan through modulation of IIS

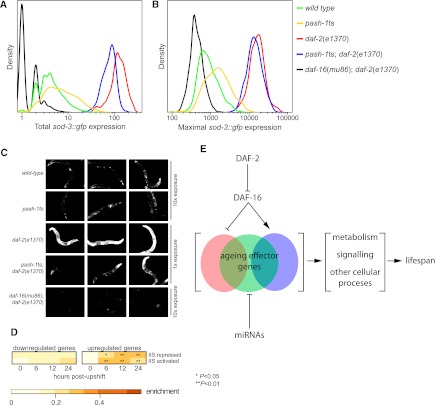

Although these data demonstrate that miRNAs and IIS regulate lifespan in part by distinct mechanisms, miRNAs might also promote longevity by inhibiting IIS. To test this, we used a sod-3∷gfp reporter transgene (Libina et al. 2003). The sod-3 promoter is directly regulated by DAF-16, and so GFP levels reflect IIS activity—increasing IIS reduces GFP expression. By use of the COPAS Biosort instrument, we profiled GFP expression over the length of hundreds of animals 24 h after upshift. We measured both the total (Fig. 6A), and peak (Fig. 6B) intensity of GFP fluorescence over the length of each animal (n > 500 for each strain). We also inspected GFP expression 5 d after upshift by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6C). As expected sod-3∷gfp expression is increased in daf-2(e1370) mutants, and this effect is lost in daf-16(mu86); daf-2(e1370) double mutants, which express GFP at lower levels than the wild type. In contrast, pash-1ts has little effect on sod-3∷gfp expression. In pash-1ts animals, GFP expression is slightly higher than wild type. This suggests IIS is slightly reduced in the absence of miRNA synthesis and is inconsistent with miRNAs promoting longevity by inhibition of IIS. pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutant animals show high expression of GFP, similar to daf-2(e1370) animals. This is consistent with the extended lifespan of pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) animals and suggests activation of DAF-16 does not require ongoing miRNA synthesis.

FIGURE 6.

miRNAs and IIS independently regulate partially overlapping gene sets. (A,B) Levels of sod-3∷gfp expression in mutants with disrupted IIS and/or miRNA synthesis, 24 h after upshift to the restrictive temperature. Histograms are from quantification of GFP expression by COPAS BIOSORT, n > 500 animals for each genotype. For each animal, we measured total GFP signal (A) and GFP intensity (B) at the brightest point along the length of the body. sod-3∷gfp expression is slightly increased in pash-1ts compared with the wild type and is slightly reduced in pash-1ts; daf-2(mj100) compared with daf-2(e1370). (C) Fluorescence micrographs showing levels of sod-3∷gfp expression 5 d after upshift of animals to 25°C. (D) Genes up-regulated in pash-1ts adults placed at the restrictive temperature are enriched for genes both activated and repressed by the IIS pathway. (E) Model for parallel regulation of lifespan by IIS and a separate miRNA-dependent pathway, converging on regulation of aging effector genes.

Although pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants show high levels of sod-3∷gfp expression compared with the wild type, the extent of GFP expression is partially reduced compared with daf-2(e1370) single mutants. Specifically, although the maximum GFP signal from each animal is similar (Fig. 6B), total GFP expression over the length of the animal is slightly reduced (Fig. 6A). This suggests that activation of sod-3∷gfp in some parts of the animal is incomplete in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) double mutants. Supporting this idea, after 5 d at the restrictive temperature, GFP expression is reduced in a subset of tissues in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) compared with daf-2(e1370) (Fig. 6C). These differences are small relative to the complete loss of GFP expression seen in daf-16(mu86); daf-2(e1370) double mutants, and GFP expression remains on average more than 10 times greater in pash-1ts; daf-2(e1370) animals than the wild-type. We conclude that although miRNAs can modulate DAF-16/IIS activity under some circumstances, the reduced lifespan of animals lacking miRNA synthesis does not occur due to misregulation of IIS.

miRNAs and IIS regulate overlapping gene sets important for longevity

Several hundred genes are regulated downstream from IIS in a DAF-16–dependent manner, many of which are directly regulated by DAF-16 and are implicated in physiological functions such as metabolism and stress responses (Lee et al. 2003; McElwee et al. 2003; Murphy et al. 2003). IIS controls aging by coordinated regulation of this set of genes: Manipulating expression of any single IIS-regulated gene has only marginal effects on lifespan. Genes up-regulated by inactivation of miRNA synthesis are enriched for IIS-regulated genes (Fig. 6D). Both IIS-repressed and IIS-activated genes are up-regulated, a pattern that is not consistent with a global change in IIS levels. Inactivation of miRNA synthesis does not markedly alter expression of the sod-3∷gfp reporter, suggesting that transcriptional regulation of DAF-16 targets downstream from IIS is unaffected. It is therefore likely that these IIS-regulated genes' expression depends on miRNAs in an IIS-independent manner. Since the coordinated regulation of this battery of genes is an important determinant of longevity, their misregulation is likely to contribute to the reduced lifespan of pash-1ts animals. Altogether, these data suggest that IIS/DAF-16 and miRNA-dependent pathway(s) regulate lifespan by independently controlling the expression of overlapping sets of genes with important physiological functions (Fig. 6E).

DISCUSSION

We have isolated a temperature-sensitive allele of the miRNA biogenesis gene DGCR8/pash-1. To our knowledge, pash-1ts is the first temperature-sensitive miRNA biogenesis mutant in any organism. We used this mutant to measure the in vivo half-life of miRNAs, and find that miRNA half-lives vary substantially, suggesting differential regulation of miRNA stability (Fig. 1F,G). DGCR8/PASH-1 is essential for development in C. elegans and other animals (Denli et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2009; Suh et al. 2010). Temperature-sensitive alleles are a powerful means to clarify the functions of essential genes and pathways, and we anticipate that pash-1ts will be of great utility in future studies of miRNA functions and mechanisms in C. elegans. Here we have utilized the pash-1ts mutant to separate the roles of miRNAs in development from those in physiology and aging.

We note the following caveats that should be considered in any analysis of miRNA functions using the pash-1ts mutant. Mirtrons, a class of miRNAs synthesized by a PASH-1–independent mechanism, are not disrupted in pash-1ts mutants. Other approaches will need to be employed to address mirtron functions. Studies in human and mouse cell lines have identified some mRNAs that are directly regulated by Drosha/DGCR8-mediated cleavage (Chong et al. 2010; Karginov et al. 2010; Macias et al. 2012). Although this has not been reported in C. elegans, it remains possible that some abnormalities observed in pash-1ts animals result from miRNA synthesis–independent functions of PASH-1. It will of interest to test whether mRNAs are also directly targeted by DRSH-1/PASH-1 in C. elegans and whether this activity is also disrupted in the pash-1ts mutant. Finally, we note that it is formally possible that some pre-miRNAs or pri-miRNAs may have functions independent of synthesis of a mature miRNAs, and these functions may also be disrupted in pash-1ts mutants. Despite these caveats, the gene expression changes we report suggest that loss of miRNAs is at least a major cause, if not the sole cause, of abnormalities in pash-1ts animals placed at the restrictive temperature.

miRNAs mediate post-developmental, post-mitotic cellular functions in animals

Here we show that ongoing miRNA expression in adults is essential for normal lifespan. As the soma of C. elegans adults is entirely post-mitotic, these data indicate that miRNAs expressed in the adult must have nondevelopmental roles critical for cellular function or viability. The fact that inactivating miRNA synthesis for a brief period can severely reduce subsequent lifespan underlines the critical nature of these functions. Restoring miRNA expression to a single tissue can increase lifespan, despite the absence of miRNA synthesis in other tissues (Fig. 3). As such our data suggest that miRNAs are not essential for cellular viability but are required for normal function of the organism. This is consistent with the viability of mammalian cell lines that lack miRNA biogenesis genes (Kanellopoulou et al. 2005; Murchison et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2007). During evolution, gene regulation by miRNAs appears to have independently arisen in multicellular lineages but is absent, with the exception of one alga, in unicellular organisms (Molnár et al. 2007). miRNA functions might be restricted to those related to multicellularity as a result of their phylogeny. The complexity of the miRNA gene sets of different animal taxa correlates with morphological and cellular complexity (Peterson et al. 2009; Erwin et al. 2011). Our data highlight that this correlation may reflect involvement of miRNAs in the physiological (as well as developmental) gene regulatory networks of these more complex organisms.

Post-developmental miRNA synthesis affects the rate of aging

In addition to reduced overall lifespan, adult animals unable to synthesize miRNAs show phenotypic and molecular signs of advanced age earlier than wild-type animals. This suggests that these animals have reduced lifespan because age-related decline occurs more rapidly than normal. Some genetic manipulations that extend lifespan can still increase longevity of animals unable to synthesize miRNAs, indicating that miRNA expression is not simply indispensable for the viability of the animal. Thus we suggest that continuous miRNA expression in adults is important for physiological functions that determine the rate of aging.

We exploited the pash-1ts mutant to test whether the ability to synthesize miRNAs is required for various mechanisms of lifespan extension. We found two mechanisms of lifespan extension—lin-14 inactivation, and JNK-1 over expression—for which miRNA synthesis is essential. In addition, lifespan extension by dietary restriction and germline ablation is less effective in absence of miRNA synthesis, suggesting miRNA synthesis is also important in these cases. Increased expression of some miRNAs could be required to mediate extended lifespan under these conditions, or miRNA expression may be required in parallel for maximal lifespan. We also found cases where the extent of lifespan extension was similar regardless of miRNA synthesis (inhibition of mitochondrial function and inhibition of IIS). So miRNAs are required for a subset of lifespan extension mechanisms but not for lifespan extension in general.

Aging regulatory pathways often act through hormones or metabolic signals that coordinate the physiology of different cells and tissues. Since restoring miRNAs to specific tissues of the animal can significantly increase lifespan, miRNAs might control the release of factors that can influence the physiology of cells that do not express miRNAs (Fig. 3). Strikingly, neuron-specific rescue of miRNA synthesis almost completely restores wild-type longevity. Neuronal degeneration is a cause of age-related decline and has recently been linked to miRNAs in Drosophila (Liu et al. 2012). However, in C. elegans, aging is not associated with neuronal degeneration, and mutations that severely disrupt neuronal development or function have neutral or beneficial effects on lifespan (Ailion et al. 1999; Apfeld and Kenyon 1999; Herndon et al. 2002). Neurons secrete signals that control metabolism and lifespan (Apfeld and Kenyon 1999; Mak et al. 2006). Abnormal neuroendocrine signaling may be a major cause of rapid aging in animals unable to synthesize miRNAs.

Coordinate control of gene expression by miRNAs and IIS regulates physiology and aging

We made the surprising observation that inactivation of the DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor extends lifespan even in animals unable to synthesize miRNAs. This lifespan extension is daf-16 dependent, indicating that DAF-16 can promote longevity by mechanisms that do not require synthesis of miRNAs. The DAF-16 transcription factor mediates the effects of IIS on lifespan via regulation of a battery of target genes (Lee et al. 2003; McElwee et al. 2003; Murphy et al. 2003). Our data suggest that this program of transcriptional regulation is sufficient to extend lifespan even in the absence of post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs.

This epistasis relationship between pash-1 and daf-2 could indicate that the reduced lifespan of animals lacking miRNA expression is due to inappropriate regulation of IIS. However, we found no evidence for increased IIS, and removal of miRNA expression reduces lifespan in a daf-16–null mutant, in which IIS cannot regulate lifespan. These data suggest that miRNAs and IIS determine lifespan in parallel. Given that animals unable to synthesize miRNAs misregulate genes also controlled by IIS/DAF-16, we suggest that coordinated regulation of common target genes shared by both pathways is important for control of physiology and, in turn, the lifespan of wild-type animals. Consistent with this suggestion, both IIS/DAF-16 activity and miRNA synthesis levels during adulthood are critical for lifespan (Dillin 2002). Further, both IIS and miRNA synthesis are required partly cell nonautonomously and act largely in the nervous system to determine lifespan (Apfeld and Kenyon 1998; Wolkow et al. 2000; Libina et al. 2003).

Previous studies have shown that the lin-4 miRNA and mir-71 are required for the extended lifespan of animals with reduced IIS. How can this be reconciled with the lifespan extension we observed by inactivation of DAF-2 in pash-1ts animals? One possibility is that these miRNAs may act via regulation of other miRNAs to modulate IIS. The fact that miRNA expression is required for the extended lifespan of lin-14 mutants supports this hypothesis in the case of the lin-4 miRNA.

In mice and Drosophila, miRNAs regulate metabolism via Insulin signaling (Poy et al. 2004; Teleman et al. 2006; Varghese et al. 2010; Trajkovski et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2011). Some miRNAs in C. elegans regulate aging via modulation of IIS; overexpression of these miRNAs can extend lifespan (Boehm and Slack 2005; de Lencastre et al. 2010), and differences in some miRNAs' expression between isogenic individuals have been reported as predictors of longevity (Pincus et al. 2011; Sánchez-Blanco and Kim 2011). Our analysis demonstrates that expression of miRNA(s) in adult animals also regulates physiology and aging independent of IIS, so implies the existence of additional miRNA determinants of lifespan. Since many individual miRNA gene knockouts or compound mutants removing entire miRNA families do not show obvious abnormalities (Miska et al. 2007; Alvarez-Saavedra and Horvitz 2010), it is likely that unrelated miRNAs act together in some of these functions. Uncovering these miRNAs and their physiological regulatory networks will be of great interest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nematode culture and strains

C. elegans were grown under standard conditions at 20°C unless otherwise indicated. The food source used was Escherichia coli strain HB101 (Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, University of Minnesota). Bleaching followed by starvation-induced L1 arrest was used to generate synchronized cultures. The wild-type strain was var. Bristol N2 (Brenner 1974). All strains used are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Genetic screens

To induce germline mutations, L4 animals were treated with 47 mM ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS; Sigma) dissolved in M9 buffer for 4 h at 20°C.

Lifespan analysis

All lifespan assays were performed at 25°C and initiated in young adults. Animals used for lifespan analysis were raised at 15°C. Late L4 stage animals were moved to new plates and kept for 24 h at 15°C. The animals, now young adults, were shifted to 25°C, and plates were checked for surviving animals daily. Animals were moved to new plates every 2 d for the first 6 d of the assay and every 3–5 d subsequently. Animals that crawled off the plate or died due to rupture or internally hatched eggs were censored, but their survival until the time of censoring is included in the data. We used R to plot survival curves, calculate mean lifespan, and perform statistical tests (Gentleman et al. 2005).

DNA constructs and transgenics

All constructs were generated using the Multisite Gateway Three-Fragment vector construction kit (Invitrogen) (Supplemental Tables S3, S4). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. To generate transgenic animals, germline transformation was performed as described (Mello and Fire 1995) Injection mixes contained 2–20 ng/μL of construct, 5–10 ng/μL of marker, and Invitrogen 1 kb ladder to a final concentration of 100 ng/μL DNA (for details, see Supplemental Information). Single copy transgenes were generated by transposase mediated integration (mosSCI) as described (Frøkjaer-Jensen et al. 2008).

COPAS Biosort analysis

A COPAS Biosort instrument (Union Biometrica) was used to simultaneously measure length (time of flight), absorbance (extinction), and fluorescence. For analysis of sod-3∷gfp expression, synchronized populations of animals were grown to late L4 at 15°C and then shifted for 24 h to 25°C. The adult animals were then harvested from plates and washed in M9 buffer prior to sorting. Data handling and analysis was performed using FlowJo (Tree Star) and R (Gentleman et al. 2005).

RNA interference assays

The cyc-1 RNAi clone was obtained from the Ahringer laboratory genome-wide RNAi library, and RNAi by feeding was performed as described (Kamath et al. 2003). cyc-1 RNAi was initiated at the L1 stage by placing bleached embryos onto freshly seeded RNAi plates. The lifespan of these animals was analyzed as described above and compared with that of animals similarly raised on empty vector RNAi bacteria.

RNA methods

For total RNA isolation, animals were harvested from plates by washing with M9. Animals were pelleted and frozen in liquid nitrogen and dissolved in 10 pellet volumes of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol. Detailed methods for Northern blotting and microarrays are provided in the Supplemental Material.

Microarray profiling

mRNA microarrays were Affymetrix Genome Arrays. miRNA microarrays were Exiqon LNA microarrays. Details can be found in Supplemental Material. Primary microarray data are also available at ftp.gurdon.cam.ac.uk.

Metabolomics methods

Detailed methods for metabolomic analysis are provided in the Supplemental Material. Assignments for metabolites detected by each technique are listed in Supplemental Data File 3. Primary data are also available at ftp.gurdon.cam.ac.uk.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (E.A.M.), Cancer Research UK (E.A.M.), the MRC (J.L.G.), and BBSRC (J.L.G.). C.C. was supported by the Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship from the EU (55621). C.A.G. was supported by grant 133388 from Conacyt, Mexico.

Author contributions: N.J.L., C.C., K.J.M., C.A.G., J.L.G., and E.A.M. conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript. N.J.L. carried out all experiments apart from the miRNA microarrays (K.J.M.) and the metabolomics (C.C.). Data analysis was performed by C.A.G.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.035402.112.

REFERENCES

- Ailion M, Inoue T, Weaver CI, Holdcraft RW, Thomas JH 1999. Neurosecretory control of aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 7394–7397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Saavedra E, Horvitz H 2010. Many families of C. elegans microRNAs are not essential for development or viability. Curr Biol 20: 367–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfeld J, Kenyon C 1998. Cell nonautonomy of C. elegans daf-2 function in the regulation of diapause and life span. Cell 95: 199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfeld J, Kenyon C 1999. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 402: 804–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP 2009. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Slack F 2005. A developmental timing microRNA and its target regulate life span in C. elegans. Science 310: 1954–1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulias K, Horvitz HR 2012. The C. elegans microRNA mir-71 acts in neurons to promote germline-mediated longevity through regulation of DAF-16/FOXO. Cell Metab 15: 439–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushati N, Cohen SM 2007. microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23: 175–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Großhans H 2009. Active turnover modulates mature microRNA activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 461: 456–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong MMW, Zhang G, Cheloufi S, Neubert TA, Hannon GJ, Littman DR 2010. Canonical and alternate functions of the microRNA biogenesis machinery. Genes Dev 24: 1951–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lencastre A, Pincus Z, Zhou K, Kato M, Lee SS, Slack FJ 2010. MicroRNAs both promote and antagonize longevity in C. elegans. Curr Biol 20: 2159–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli AM, Tops BBJ, Plasterk RHA, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ 2004. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 432: 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillin A 2002. Timing requirements for insulin/IGF-1 signaling in C. elegans. Science 298: 830–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillin A, Hsu A-L, Arantes-Oliveira N, Lehrer-Graiwer J, Hsin H, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Kenyon C 2002. Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science 298: 2398–2401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbein AD, Pan YT, Pastuszak I, Carroll D 2003. New insights on trehalose: A multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology 13: 17R–27R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DH, Laflamme M, Tweedt SM, Sperling EA, Pisani D, Peterson KJ 2011. The Cambrian conundrum: Early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science 334: 1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AL, Lithgow GJ 2006. The nuclear hormone receptor DAF-12 has opposing effects on Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan and regulates genes repressed in multiple long-lived worms. Aging Cell 5: 127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP 2008. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19: 92–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frøkjaer-Jensen C, Davis MW, Hopkins CE, Newman BJ, Thummel JM, Olesen S-P, Grunnet M, Jorgensen EM 2008. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet 40: 1375–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Irizarry R, Dudoit S 2005. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Golden TR, Hubbard A, Dando C, Herren MA, Melov S 2008. Age-related behaviors have distinct transcriptional profiles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 7: 850–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Yan K-P, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R 2004. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432: 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, Ha I, Baillie DL, Fire A, Ruvkun G, Mello CC 2001. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell 106: 23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M 2002. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature 419: 808–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu A-L, Murphy CT, Kenyon C 2003. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science 300: 1142–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez-Ventoso C, Yang M, Guo S, Robins H, Padgett RW, Driscoll M 2006. Modulated microRNA expression during adult lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 5: 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan CH, Friedman RC, Ruby JG, Bartel DP 2011. Formation, regulation and evolution of Caenorhabditis elegans 3′ UTRs. Nature 469: 97–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, Livingston DM, Rajewsky K 2005. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev 19: 489–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karginov FV, Cheloufi S, Chong MMW, Stark A, Smith AD, Hannon GJ 2010. Diverse endonucleolytic cleavage sites in the mammalian transcriptome depend upon microRNAs, Drosha, and additional nucleases. Mol Cell 38: 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ 2010. The genetics of ageing. Nature 464: 504–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R 1993. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366: 461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH 2001. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev 15: 2654–2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S 2010. miRBase: Integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D152–D157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J, Busskamp V, Markiewicz I, Stadler MB, Ribi S, Richter J, Duebel J, Bicker S, Fehling HJ, Schübeler D, et al. 2010. Characterizing light-regulated retinal microRNAs reveals rapid turnover as a common property of neuronal microRNAs. Cell 141: 618–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamitina ST, Strange K 2005. Transcriptional targets of DAF-16 insulin signaling pathway protect C. elegans from extreme hypertonic stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C467–C474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V 1993. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Kennedy S, Tolonen AC, Ruvkun G 2003. DAF-16 target genes that control C. elegans life-span and metabolism. Science 300: 644–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrbach NJ, Armisen J, Lightfoot HL, Murfitt KJ, Bugaut A, Balasubramanian S, Miska EA 2009. LIN-28 and the poly(U) polymerase PUP-2 regulate let-7 microRNA processing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 1016–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120: 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C 2003. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell 115: 489–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Hsin H, Libina N, Kenyon C 2001. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat Genet 28: 139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Landreh M, Cao K, Abe M, Hendriks G-J, Kennerdell JR, Zhu Y, Wang L-S, Bonini NM 2012. The microRNA miR-34 modulates ageing and neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature 482: 519–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias S, Plass M, Stajuda A, Michlewski G, Eyras E, Cáceres JF 2012. DGCR8 HITS-CLIP reveals novel functions for the Microprocessor. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19: 760–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak HY, Nelson LS, Basson M, Johnson CD, Ruvkun G 2006. Polygenic control of Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage. Nat Genet 38: 363–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Smibert P, Yalcin A, Tyler DM, Schäfer U, Tuschl T, Lai EC 2009. A Drosophila pasha mutant distinguishes the canonical microRNA and mirtron pathways. Mol Cell Biol 29: 861–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez NJ, Ow MC, Barrasa MI, Hammell M, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Roth FP, Ambros VR, Walhout AJM 2008a. A C. elegans genome-scale microRNA network contains composite feedback motifs with high flux capacity. Genes Dev 22: 2535–2549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez NJ, Ow MC, Reece-Hoyes JS, Barrasa MI, Ambros VR, Walhout AJM 2008b. Genome-scale spatiotemporal analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans microRNA promoter activity. Genome Res 18: 2005–2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee J, Bubb K, Thomas JH 2003. Transcriptional outputs of the Caenorhabditis elegans forkhead protein DAF-16. Aging Cell 2: 111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Fire A 1995. DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol 48: 451–482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miska E, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Abbott A, Lau N, Hellman A, McGonagle S, Bartel D, Ambros V, Horvitz H 2007. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet 3: e215 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár A, Schwach F, Studholme DJ, Thuenemann EC, Baulcombe DC 2007. miRNAs control gene expression in the single-cell alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Nature 447: 1126–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ 2005. Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 12135–12140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C 2003. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 424: 277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, Patterson GI, Lee L, Tissenbaum HA, Ruvkun G 1997. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature 389: 994–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SW, Mukhopadhyay A, Svrzikapa N, Jiang F, Davis RJ, Tissenbaum HA 2005. JNK regulates lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulating nuclear translocation of forkhead transcription factor/DAF-16. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 4494–4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panowski SH, Wolff S, Aguilaniu H, Durieux J, Dillin A 2007. PHA-4/Foxa mediates diet-restriction-induced longevity of C. elegans. Nature 447: 550–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson KJ, Dietrich MR, McPeek MA 2009. MicroRNAs and metazoan macroevolution: Insights into canalization, complexity, and the Cambrian explosion. Bioessays 31: 736–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus Z, Smith-Vikos T, Slack FJ 2011. MicroRNA predictors of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 7: e1002306 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krützfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, et al. 2004. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature 432: 226–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G 2000. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403: 901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Blanco A, Kim SK 2011. Variable pathogenicity determines individual lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 7: e1002047 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw WM, Luo S, Landis J, Ashraf J, Murphy CT 2007. The C. elegans TGF-β Dauer pathway regulates longevity via insulin signaling. Curr Biol 17: 1635–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Baehner L, Moltzahn F, Melton C, Shenoy A, Chen J, Blelloch R 2010. MicroRNA function is globally suppressed in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Curr Biol 20: 271–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M 2003. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science 299: 1346–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman AA, Maitra S, Cohen SM 2006. Drosophila lacking microRNA miR-278 are defective in energy homeostasis. Genes Dev 20: 417–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovski M, Hausser J, Soutschek J, Bhat B, Akin A, Zavolan M, Heim MH, Stoffel M 2011. MicroRNAs 103 and 107 regulate insulin sensitivity. Nature 474: 649–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullet JMA, Hertweck M, An JH, Baker J, Hwang JY, Liu S, Oliveira RP, Baumeister R, Blackwell TK 2008. Direct inhibition of the longevity-promoting factor SKN-1 by insulin-like signaling in C. elegans. Cell 132: 1025–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese J, Lim SF, Cohen SM 2010. Drosophila miR-14 regulates insulin production and metabolism through its target, sugarbabe. Genes Dev 24: 2748–2753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R 2007. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet 39: 380–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker NC, Habig JW, Bass BL 2007. Genes misregulated in C. elegans deficient in Dicer, RDE-4, or RDE-1 are enriched for innate immunity genes. RNA 13: 1090–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G 1993. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75: 855–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkow CA, Kimura KD, Lee MS, Ruvkun G 2000. Regulation of C. elegans life-span by insulinlike signaling in the nervous system. Science 290: 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Fire AZ 2010. Cell autonomous specification of temporal identity by Caenorhabditis elegans microRNA lin-4. Dev Biol 344: 603–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Shyh-Chang N, Segrè AV, Shinoda G, Shah SP, Einhorn WS, Takeuchi A, Engreitz JM, Hagan JP, Kharas MG, et al. 2011. The Lin28/let-7 axis regulates glucose metabolism. Cell 147: 81–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisoulis D, Lovci M, Wilbert M, Hutt K, Liang T, Pasquinelli A, Yeo G 2010. Comprehensive discovery of endogenous Argonaute binding sites in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 173–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]