The authors have shown previously that simple RNA structures bind pure phospholipid liposomes. However, binding of bona fide cellular RNA under physiological ionic conditions is shown here for the first time. Human tRNASec contains a hydrophobic anticodon-loop modification: N6-isopentenyladenosine (i6A) adjacent to its anticodon. Using a highly specific double-probe hybridization assay, the authors show mature human tRNASec specifically retained in HeLa intermediate-density membranes. Further, isolated human tRNASec rebinds to liposomes from isolated HeLa membrane lipids, to a much greater extent than an unmodified tRNASec transcript.

Keywords: RNA, phospholipid, bilayer, rafts, sphingosine

Abstract

We have shown previously that simple RNA structures bind pure phospholipid liposomes. However, binding of bona fide cellular RNAs under physiological ionic conditions is shown here for the first time. Human tRNASec contains a hydrophobic anticodon-loop modification: N6-isopentenyladenosine (i6A) adjacent to its anticodon. Using a highly specific double-probe hybridization assay, we show mature human tRNASec specifically retained in HeLa intermediate-density membranes. Further, isolated human tRNASec rebinds to liposomes from isolated HeLa membrane lipids, to a much greater extent than an unmodified tRNASec transcript. To better define this affinity, experiments with pure lipids show that liposomes forming rafts or including positively charged sphingosine, or particularly both together, exhibit increased tRNASec binding. Thus tRNASec residence on membranes is determined by several factors, such as hydrophobic modification (likely isopentenylation of tRNASec), lipid structure (particularly lipid rafts), or sphingosine at a physiological concentration in rafted membranes. From prior work, RNA structure and ionic conditions also appear important. tRNASec dissociation from HeLa liposomes implies a mean membrane residence of 7.6 min at 24°C (t½ = 5.3 min). Clearly RNA with a 5-carbon hydrophobic modification binds HeLa membranes, probably favoring raft domains containing specific lipids, for times sufficient to alter biological fates.

INTRODUCTION

RNAs that bind and change the properties of lipid bilayers, composed solely of nonmodified, normal ribonucleotides, have been selected and characterized (Khvorova et al. 1999; Vlassov et al. 2001; Janas and Yarus 2003). We have called these “membrane RNAs.” In random-sequence RNA, domains with membrane affinity are not observable. However, binding activity is easily selected. Thus, specific nucleotide sequences are required for enhanced affinity to phospholipid bilayers but such RNA domains, judging from ease of selection, must be small and numerous. By combining such preselected RNA–membrane affinity domains with an RNA amino acid binding RNA site, a passive membrane transporter specifically directed to the amino acid tryptophan was constructed and characterized (Janas et al. 2004). This membrane RNA, composed only of the four standard ribonucleotides, is specific to the amino acid side chain and transports tryptophan at a rate that overlaps proteins carrying out a similar membrane transport reaction. For review of RNA and lipid bilayer interactions, see Janas et al. (2005).

RNA binding is sensitive to membrane lipid structure. Membrane rafts are liquid-ordered domains composed of saturated lipids (phospholipids, sphingolipids) and cholesterol (Quinn 2010). Upon intra- or extracellular stimuli, fluctuating nano-scale rafts can coalesce into larger platforms and micro-scale raft phases (Simons and Gerl 2010). Micro-scale phase separation in synthetic model systems (composed of sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and unsaturated phospholipids) has been recapitulated in isolated plasma membrane vesicles (Levental et al. 2011). Structure-dependent binding of nonmodified RNAs is enhanced by rafted (liquid-ordered) domains in DOPC-sphingomyelin-cholesterol vesicles. Selective RNA presence at lipid rafts and edges in liposomal membranes was visualized using FRET microscopy (Janas et al. 2006).

A particular lipid of potential relevance to RNA is sphingosine, a single-chain sphingolipid. It is concentrated in membrane rafts, where it is phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase (Hengst et al. 2009). Galactosyl-sphingosine (psychosine) also accumulates in membrane rafts and alters their architecture (White et al. 2009). In most cell types, sphingosine is present in concentrations that are an order of magnitude lower than that of ceramide which in turn is an order of magnitude lower than sphingomyelin (Hannun and Obeid 2008). Therefore, hydrolysis of only a few percent of ceramide can double the level of sphingosine. Human ceramidase, localized to the Golgi complex in human HeLa cells, controls the hydrolysis of ceramides (Xu et al. 2006). Ceramidases are also concentrated in particular tissues, overexpressed in several cancer cell lines and cancer tissues (Gangoiti et al. 2010) including HeLa cells (Sun et al. 2009). In cultured neural cells, both C18 and C20 sphingosines were detected (Valsecchi et al. 1996). Sphingosine has an amino pK between 7 and 9 depending on the membrane surface charge, the chemical structure of the membrane-solution interface, and the ionic strength of the solution. Thus sphingosine molecules in membranes are partially positively charged and potentially interact with RNA at physiological pH, with a specific distribution among membrane systems (summarized in Janas et al. 2011).

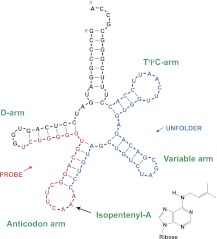

We focus on tRNASec, the UGA-specific tRNA that carries the amino acid selenocysteine into selenoproteins in archaea, eukaryotes, and certain bacteria (Yuan et al. 2010). tRNASec is the largest among known mature tRNA species with a long variable arm and an extended acceptor arm (Fig. 1; Itoh et al. 2009). The latter is the result of an unusual RNase P 5′-leader cleavage specificity (Burkard and Söll 1988). Thus, human tRNASec contains 90 nt rather than the 75–77 nt of canonical tRNA molecules (Palioura et al. 2009). Several modified nucleotides occur in human tRNASec including N6-isopentenyladenosine (i6A) at position 37 (Kato et al. 1983). The nucleotide A37, modified by the hydrophobic 5-carbon isoprene chain, is 3′-adjacent to the anticodon UCA. The transfer of this isoprene from dimethylallyl diphosphate to the N6-amino group of A37 in the tRNA substrate is catalyzed by the tRNA-isopentenyltransferase (Zhou and Huang 2008). Our interest originates from the possibility that the isoprene modification might function to confer affinity for the hydrophobic layer of cellular membranes.

FIGURE 1.

Secondary structure of human tRNASec. The drawing is the output of BayesFold (Knight et al. 2004). The black arrow marks the isopentenylated A37. The nucleotides in blue are the region complementary to the 37-nt oligoDNA unfolder and the nucleotides in red are the region complementary to the 20-nt 32P-labeled oligoDNA probe for Northern blot analysis.

We have tested this hypothesis by comparing modified and unmodified forms of the tRNASec sequence. Below, we demonstrate enhanced affinity of isoprenylated, negatively charged tRNASec to HeLa membranes, HeLa lipid vesicles, and rafted synthetic liposomes, and show that it can be attributed to the summed effect of at least three factors: hydrophobic modifications of tRNASec, the presence of membrane rafts, and the addition of positively charged sphingosine, presumably concentrated within rafted subdomains.

RESULTS

We wished to follow normal human tRNASec (Fig. 1) in the presence of lipid bilayers to see whether it might have an unusual association with HeLa membranes. Therefore, we prepared membrane fractions from HeLa cells and measured tRNASec by double-probe hybridization (Buvoli et al. 2000), a technique which gives greatly sensitized detection of structured RNAs, including tRNA. As we will show below, this centrifugation technique is adequate to detect membrane affinity, but is likely too slow to recover RNA–membrane complexes quantitatively.

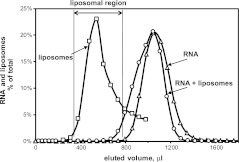

In addition, we extracted tRNASec from these membranes, and tested rebinding to liposomes composed of varied lipids. Figure 2 exhibits the technique in which Sephacryl gel filtration is used to pool RNAs associated with liposomes, by pooling RNAs that elute with the liposome peak. As Figure 2 shows, RNA levels in liposome fractions are very low in the absence of HeLa lipid liposomes. Collection of column fractions takes ∼12 min, and therefore is more sensitive to transient complex formation than is ultracentrifugation.

FIGURE 2.

Affinity of total HeLa RNA to liposomes, prepared from lipids extracted from HeLa membranes, measured by gel filtration on Sephacryl S-1000. 3′-end labeled [32P]RNA incubated (triangles) and not incubated (circles) with liposomes (as OD400, squares). The horizontal arrow indicates the liposomal region.

Specificity of the double Northern signal

To characterize the Northern signal, we measured proportionality to the amount of tRNASec. In a control, double-probe radioactivity (Fig. 3A) was linearly related to the amount of total HeLa RNA and presumably to its tRNASec. In an interference control (Fig. 3B), a constant amount (200 ng) of HeLa RNA containing tRNASec was mixed with different amounts of an irrelevant mixed RNA (total Escherichia coli RNA). The total concentration of RNA in the sample has only a minor effect on the Northern signal from the minority of tRNASec. Thus the technique of double-probe tRNA hybridization, sensitized to labeled probe by an adjacent unlabeled oligonucleotide “unfolder” (Buvoli et al. 2000), is both linear and specific to tRNASec.

FIGURE 3.

Specificity of the double Northern signal. (A) A linearity control. (B) An interference control. The ordinates represent the Northern signal of tRNASec as a fraction of the maximal signal.

Binding of tRNASec to HeLa membranes detected by double Northern

Figure 4A presents the specific concentrations of tRNASec in the sucrose fractionated HeLa cell membranes, compared with the specific concentration in fraction C (cell homogenate; the broken line) which was applied to the sucrose gradient. Enhancement of tRNASec specific activity is observed only in the intermediate-membrane fraction 8s (enriched in Golgi membranes and plasma membranes). Thus a cellular membrane fraction specifically retains cellular tRNASec, though we cannot eliminate enclosure in vesicles, binding to membrane proteins, or other causes unrelated to direct RNA–membrane affinity. In addition, we expect that RNA–membrane association is minimized in this experiment, because the 90-min gradient centrifugation necessarily provides time for RNA dissociation from membranes (see below).

FIGURE 4.

Enrichment of tRNASec in membrane fractions as measured by the double-probe Northern. (A) Specific concentration of tRNASec in the sucrose fractions 3s, 8s, and 12s containing HeLa cell membranes. The broken line represents the specific concentration of tRNASec in fraction C, applied to the sucrose gradient for the fractionation. (B) Affinity of tRNASec for liposomes (“lipos”) composed of lipids extracted from HeLa cell membranes. RNA was separately extracted from HeLa cells (“total RNA”) and from sucrose gradient fractions (“fract”) 3s, 8s, and 12s. The ordinate (specific concentration of tRNASec) represents the mass of tRNASec under the liposomal region divided by the mass of all RNAs under the liposomal region. Bars are the standard error of the mean (three experiments).

Binding of tRNASec to HeLa liposomes detected by double Northern

To characterize the tRNASec–membrane interaction under more defined conditions, we extracted RNA from sucrose-density membrane fractions 3s (heavy, mostly ER membranes), 8s (intermediate density, mostly plasma and Golgi membranes), and 12s (light membranes) and tested rebinding of endogenous tRNASec to liposomes prepared from HeLa cell lipids. We quantified the specific activity of tRNASec (as fg of tRNASec per ng of RNA extracted) using a double-probe Northern blot specific for human tRNASec (Fig. 1) and RiboGreen fluorescence measurements for total extracted RNAs.

Figure 4B shows that tRNASec in the HeLa liposome region increases in specific activity sixfold, compared with a control applied to the column without liposomes (Fig. 2), after incubation with total HeLa homogenate RNAs. Bound material is 5% of total tRNASec. The specific activity increases 2.5-fold for the same comparison with heavy membrane fraction 3s RNA, and fivefold for intermediate-membrane fraction 8s RNA. There is a 1.3-fold increase in the case of fraction 12s, which seems statistically insignificant. In addition, there was about a 1.27-fold increase in the specific concentration of nonmodified tRNASec transcript (which was mixed with total E. coli RNA before the binding assay to liposomes) under the liposomal region. The assay measures gel mobility, which reveals a sharp band of hybridization at the mobility characteristic of tRNASec, confirming the specificity of the double-probe hybridization and the identity of the target, whose signal requires hybridization to 57 total nucleotides.

Thus while only small effects are observed with unmodified tRNASec transcript, heavy and intermediate-density HeLa membranes contain tRNASec which specifically reassociates with HeLa lipid liposomes. These data therefore confirm and potentially explain the association of tRNASec with more slowly fractionated cell membranes (Fig. 4A).

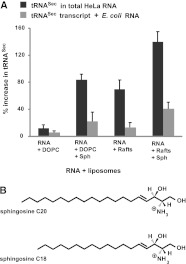

Effect of lipid composition and sphingosine on tRNASec binding to liposomes

To better associate tRNASec binding with specific lipid structures, we used liposomes made from pure lipids. Liposomes composed of an unsaturated lipid, sphingomyelin, and cholesterol exhibit phase separation in which sphingomyelin and cholesterol form liquid-ordered domains, often used as a model for membrane rafts (Janas et al. 2006; Quinn 2010). Phospholipids diffuse within the liquid-ordered bilayer as in the fully fluid state, while keeping fatty acyl chains in an extended, kink-free conformation as in the more ordered gel phase.

We measured affinities to liposomes made of synthetic phospholipids:

DOPC only (fluid DOPC liposomes);

DOPC liposomes with 0.3 mol% of sphingosine (fluid membranes with cationic charge);

DOPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol 60:30:10 mol ratio with 0.3 mol% of sphingosine (rafted liposomes with cationic charge).

Since the rafted liposomes contain 30 mol% of sphingomyelin, the 100-fold mole ratio of sphingomyelin to sphingosine in the rafted liposomes mimics the mole ratio of sphingomyelin to sphingosine in human cell membranes (Hannun and Obeid 2008).

Total HeLa RNA (5 μg) which contains tRNASec, or E. coli RNA (5 μg) supplemented with 120 ng of tRNASec transcript were applied to a Sephacryl gel filtration column that voids all liposomes. As in Figure 2, RNA present under the liposomal peak in a high ionic strength “physiological” buffer was extracted and assayed by Northern blot.

In Figure 5A the increase in the specific concentration of tRNASec or its transcript in the liposome fraction is summarized. The increase is given in relation to the specific concentration of tRNASec when total HeLa RNA was applied on the column without liposomes. There is only a small increase in cellular tRNASec binding to fluid DOPC liposomes in comparison to tRNASec transcript, insignificant with respect to the standard error of the mean (bars). However, for rafted liposomes, this increase in specific activity of HeLa tRNASec is 5.7-fold. Cellular levels of sphingosine (Fig. 5B) added to DOPC liposomes yield a 3.5-fold increase in tRNASec fractionation with respect to unmodified transcript, and rafted liposomes without sphingosine increase the binding of tRNASec by about the same factor. With both rafts and sphinosine we observe the highest levels of co-eluting tRNASec, but also increase the affinity of unmodified transcript for these liposomes. These results suggest that the presence of a modification, probably principally the A37 isoprenyl modification, allows for stronger insertion of tRNASec into a rafted and sphingosine-containing bilayer, though, as might be expected, the (probably electrostatic) stimulation effect of sphingosine does not distinguish transcript and native tRNASec.

FIGURE 5.

(A) Effect of lipid composition and sphingosine (Sph) on tRNASec and nonmodified tRNASec transcript binding to liposomes composed of chemically defined lipids. (B) Structure of sphingosines C20 and C18. Bars represent the standard error of the mean (three experiments).

Rate constant of tRNASec dissociation from HeLa liposomes

We rapidly isolated tRNASec–HeLa lipid liposome complexes by an initial spin gel filtration, and then, at intervals, rapidly respun aliquots of the initial complexes through a gel filtration column to follow dissociation of the tRNA from the vesicle (Fig. 6). Dissociation was first order, within the accuracy of the experiment. These data therefore support the idea that tRNASec is adsorbed to a single kinetic compartment, the liposome surface. In addition, the dissociation rate constant is 0.0022 sec−1 (t1/2 = 5.25 min; mean residence lifetime = 7.6 min) at 24°C (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Kinetics of tRNASec dissociation from liposomes. The first-order dissociation rate constant, kdiss, for dissociation of native tRNASec from HeLa lipid liposomes was determined using rapid resolution of RNA and liposomes by spun gel filtration at 100g.

DISCUSSION

Modified cellular human tRNASec specifically fractionates with intermediate-density HeLa membranes (Fig. 4A). Note that the time required for sucrose gradient centrifugation of membrane fractions (>1.5 h at 4°C) is much longer than the half-time (5 min 15 sec at 24°C) of the tRNASec dissociation from HeLa liposomes in similar conditions. Therefore the dissociation of tRNASec directly bound to membranes during centrifugation is presumably extensive. Thus we emphasize only the positive result: Cellular tRNASec is associated with intermediate-density cell membranes (Fig. 4A), but we cannot eliminate losses from the other membrane fractions during density centrifugation.

tRNASec also has affinity to liposomes prepared from total membrane lipids extracted from HeLa cells (Fig. 4B), a property much less marked in an unmodified transcript with the same sequence. tRNASec selectively fractionates with synthetic lipid liposomes that form rafts within the liposomal membrane (Janas et al. 2006). In addition to the isopentenylated A37, other modified nucleosides in vertebrate tRNASec include (summarized in Itoh et al. 2009) 5-methylcarboxymethyluridine (mcm5U) or O2′-methylated mcm5U (mcm5Um) at position 34, pseudouridine (Ψ) at position 55, and 1-methyladenosine (m1A) at position 58. An isopentenyl chain, together with the three to four methyl groups, seems to offer a major change in the hydrophobic-hydrophilic balance of a tRNASec molecule. We therefore suggest that at least three factors are important for binding of the negatively charged native tRNASec to the lipid bilayer:

Modification, probably mostly due to isopentenylation of tRNASec (Fig. 4), confers membrane affinity via the hydrophobic interaction between the isoprenyl and the hydrophobic interior of the membrane. A similar anchor effect is known for the binding of myristoylated (or farnesylated) proteins with a polybasic domain: In this case, hydrophobic and electrostatic forces synergize (for review, see Resh 2006). Ten of 14 methylene carbons penetrate hydrophobically into the lipid bilayer and basic amino acids associate electrostatically with negatively charged membrane phospholipids. The binding energy increases 0.8 kcal/mol for each CH2 group added to the hydrocarbon chain: for myristoylated proteins, this adds 8 kcal/mol to binding free energy (Murray et al. 1997).

Rafts within the lipid bilayer (Fig. 5). We previously showed enhanced structure-dependent RNA binding for bilayers with increased lipid structure, particularly rafted domains in liposomal membranes (Janas et al. 2006). These observations extend that prior observation to a new RNA system. Lipidated proteins have increased affinity for the periphery of membrane rafts. For example, N-Ras protein was found to localize to favor the boundary region of mixed-phase liquid-ordered/liquid-disordered bilayer domains (Weise et al. 2010). Since we also previously observed that membrane RNAs associate with the edges of lipid patches (Janas and Yarus 2003), it seems possible that tRNASec also may be concentrated at raft boundaries, and with their associated defects in lipid packing.

Sphingosine at physiological abundance (1% of the concentration of sphingomyelin) in the membrane (Fig. 5) also enhances binding. The enhancement is likely due to the positive surface charge and also perhaps to the rigidifying effect of sphingosine on lipid ordered domains in lipid bilayers (Contreras et al. 2006; Goni and Alonso 2006). At low relative concentrations, long-chain bases form aggregates in DOPC monolayers (Janas et al. 2011) and these aggregates likely exist in a lipid gel phase (Vankin 2003). Perhaps both charge and lipid conformation combine to reinforce RNA affinity. We previously found the strongest binding of RNAs to highly ordered gel phase membranes (Janas et al. 2006), and these observations reinforce the suggestion in a new system.

We previously have shown (Janas et al. 2006) that RNA structure and the ionic strength of the buffer can also modulate RNA–membrane interactions. Affinity of RNA for bilayers in ripple gel phase is apparently dominated by polar forces; it declines with increased NaCl concentration (Janas et al. 2006). The effect of RNA structure is also large; the extent of RNA binding to rafted bilayers varies ≥20-fold for different small RNA structures (Janas et al. 2006). Adopting the assumption that an RNA with a potentially large and dispersed set of membrane interactions will show largely additive free energies from its separate potential interactions, we predict that the net affinity of an RNA for a lipid bilayer will reflect the sum of its interactions due to ribonucleotide structure and nucleotide modification, as modulated by membrane lipid structure (rafting and other ordering), lipid charge, and effective solution ionic strength. We may be able to extend these conclusions to cells by visualizing fluorescent-labeled tRNASec (Janas and Yarus 2003; Janas et el. 2006).

Cellular RNAs are sometimes associated with lipid bilayers, e.g., the Xlsirt RNA and VegT RNA in Xenopus oocytes (for review, see Janas et al. 2005), RNase P in E. coli (Miczak et al. 1991), and unspliced XBP1 mRNA (Yanagitani et al. 2009). Certain mRNAs in E. coli are localized at the inner membrane in a translation-independent manner (Nevo-Dinur et al. 2011) with the transmembrane-coding sequence of mRNA being necessary and sufficient for mRNA targeting to the membrane. The 3′-UTR mediates the membrane localization of an mRNA encoding a short plasma membrane protein in yeast (Loya et al. 2008), and the nascent peptide appears too short to reach the membrane. Circulating microRNAs are associated with vesicles (multivesicular bodies, exosomes, or microvesicles) and high-density lipoproteins (Vickers et al. 2011; Creemers et al. 2012). In these cases the role of direct RNA binding to lipid bilayers has not been determined. However, regulatory small RNAs with microRNA-like features (Pederson 2010) derived from cleavage of tRNASec are likely human membrane RNAs because some reported reads overlap isopentenylated nucleotide 37 (Cole et al. 2009).

One can imagine cellular functions for RNA–membrane affinity. tRNA splicing endonucleases are localized on yeast mitochondria (Yoshihisa et al. 2003), and human tRNA isopentenyl transferase has a possible mitochondrial targeting signal (Golovko et al. 2000). Several modification reactions occur while tRNA is in a precursor form (Carell et al. 2012); thus it is conceivable that membrane affinity anchors isopentenylated pre-tRNASec to the mitochondrial outer surface during splicing. Indeed, transient or permanent membrane residence might stimulate any RNA process with a slow or rare membrane phase. For example, antisense oligonucleotides and siRNAs conjugated to neutral lipids (including long-chain isoprenoid lipids) exhibit facilitated trans-membrane delivery into cells (Raouane et al. 2012). Permanent or transient modification with small lipids might generally enhance movement, permanent or transient, of RNAs between subcellular compartments.

Thus, some cellular RNAs localize with membranes, and binding to membrane proteins is not the only, or in some cases, even the most probable explanation of binding. Present experiments suggest that RNA affinity for a phospholipid bilayer can be intrinsic property, built into RNA sequences or into RNA modifications. In addition, RNA affinity can be built into specific membrane sites by adjusting lipid structure and composition, and further modulated by the ion atmosphere, to suit varied biological functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Complete, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets were purchased from Roche. Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) was obtained from Hyclone. TRIzol-LS Reagent, RiboGreen fluorescence probe, and RNase OUT (recombinant ribonclease inhibitor) were purchased from Invitrogen. 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), cholesterol (CHOL), N-stearoyl-D-erythro-sphingosylphosphorylcholine (Stearoyl Sphingomyelin, SM), sphingosine C18, and sphingosine C20 (Fig. 5B) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Amersham Hybond-N+ membranes were purchased from GE Healthcare.

HeLa cell culture and membrane fractionation

HeLa cells were grown at 37°C in spinner flasks in minimum Joklik's modified essential medium and supplemented with 10% serum, penicillin (100 units/mL cell suspension), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL cell suspension). Prior to harvesting, cells were incubated for 10 min with cycloheximide (10 μg/mL cell suspension) to prevent ribosomal detachment from ER membranes (Mechler 1987).

Membrane fractionation utilized a published method (Radhakrishnan et al. 2008). Fifty milliliters of cell suspension (about 108 cells) was centrifuged at 500g for 10 min at room temperature. Collected cells were washed twice with 2 mL of ice-cold Buffer (W): 150 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) at 4°C, and resuspended in 1 mL of ice-cold homogenization Buffer (H): Buffer (W) with added 15% sucrose, 2 mM DTT, and supplemented with cycloheximide (10 μg), RNAse OUT 300 units, and 1/5 tablet of Complete, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail. Then cells were disrupted by passage 10 times through a ball-bearing homogenizer. The homogenized cells (fraction A) were centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (fraction C) was collected, diluted to a total volume of 3 mL using Buffer (W) containing 15% sucrose and applied to a discontinuous gradient containing 45%–30%–15%–7.5% sucrose. After centrifugation at 100,000g for 1 h at 4°C and unbraked arrest (∼30 min), fractions of 0.8 mL (1s to 12s) were collected from the bottom of the tube. There were visible membrane bands in fractions 3s, 8s, and 12s. The Western blot analysis of the distribution of membrane protein markers within these fractions was as performed (Radhakrishnan et al. 2008)—ER membrane marker appeared in heavy-membrane fractions (3s), Golgi membranes and plasma membrane markers in the intermediate light-membrane fractions (8s), and plasma membrane markers in the light-membrane fractions (12s).

Extraction of RNA and lipids from HeLa cells

HeLa cell RNA and RNA from sucrose gradient fractions (3s, 8s, 12s) were extracted by TRIzol-LS Reagent using the manufacturer's protocol and 3′-end radiolabeled (Janas et al. 2010) if needed.

For lipid extraction, HeLa cells were obtained, treated, and homogenized as described above. Membranes of HeLa cells were isolated from fraction C (supernatant obtained from homogenized cells). Fraction C (6 × 1 mL) was centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 h to yield a pellet. Lipids were extracted from the pelleted membranes using chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) according to Folch et al. (1957). TLC analysis of the lipid extract showed major phospholipids (including phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidyletanolamine, and sphingomyelin) and cholesterol, in agreement with published composition data (Cluett and Machamer 1996).

Preparation of unilamellar vesicles

Appropriate lipids were dissolved in chloroform or chloroform/methanol (2/1). Lipid solvents were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas, followed by desiccation under vacuum for at least 2 h. Lipids were resuspended at 70°C (above the main transition temperature of most cellular lipids including sphingomyelin) in buffer mimicking the intracellular water phase (buffer C): 140 mM KCl, 11 mM Na+, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0. Multilamellar liposomes were formed by gentle vortex. The suspension was subjected to seven freeze-thaw cycles by repeated immersion in liquid nitrogen followed by heating in 70°C water.

Liposomes were prepared by extrusion of this suspension at 70°C using the Avanti MiniExtruder with a filter pore diameter of 100 nm (Janas et al. 2006). Liposomes prepared from lipids extracted from HeLa cell membranes are referred to as “HeLa liposomes.” Liposomes prepared from pure DOPC were designated as “DOPC liposomes.” Liposomes prepared from DOPC/sphingomyelin/cholesterol (60:30:10 mol%, respectively) were designated as “rafted liposomes.” For liposomes (DOPC or rafted) with sphingosine (Sph), equimolar C18 sphingosine and C20 sphingosine were added, prior to liposome formation, to the lipids in organic solvents (0.3 mol% total sphingosine/mol lipids).

Preparation of nonmodified tRNASec transcript

In vitro transcription of the 90-nt nonmodified human tRNASec transcript was carried out according to Milligan and Uhlenbeck (1989). A PCR fragment containing the T7 promoter was obtained using synthetic DNAsec template and the primers 5′-TGGCGCCCGAAAGGTGGAATT-3′ and 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGCCCGGATGATCCTCAGTGGT-3′. T7 RNA polymerase transcript was gel-purified and ethanol-precipitated.

Gel filtration: RNA–liposome binding

RNA (5 μg) in water was heated for 5 min at 70°C, brought to 1× Buffer (C) (140 mM KCl, 11 mM Na+, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0), and allowed to fold while cooling to room temperature for 10 min. The appropriate liposomes (10 mg/mL) were incubated with RNA for 5 min at room temperature then applied to a 1-mL Sephacryl S-1000 Superfine column and eluted with Buffer (C) at 24°C. A Sephacryl S-1000 Superfine column admits lipid vesicles with diameters up to 300 nm for fractionation. Co-elution of RNA and liposomes is used to measure binding. Fractions under the liposomal peak (see Fig. 2) were pooled and RNA was extracted for tRNASec Northern blot analysis.

The following RNAs were analyzed: total Hela RNAs, RNAs from sucrose fractions (3s, heavy-membrane fraction; 8s, intermediate-membrane fraction; and 12s, upper, light-membrane fractions), 1 ng of nonmodified tRNASec transcript mixed with 5 μg of total E. coli RNAs (which is otherwise free of human tRNASec). Eluted samples were analyzed for [32P] RNA by scintillation counting, for liposome concentration by OD400 turbidity, and RNA concentration by the RiboGreen assay (Jones et al. 1998).

Northern blot analysis

RNAs extracted from the liposomal region (see Fig. 2) were precipitated. Northern blot analysis was performed according to the adjacent oligonucleotide technique of Buvoli et al. (2000). A 37-nt oligoDNA unfolder (5′-GTGGAATTGAACCACTCTGTCGCTAGACAGCTACAGG-3′) was applied during prehybridization (see Fig. 1) to disrupt the target tRNASec secondary/tertiary structures. An immediately adjacent 20-nt 32P-labeled DNA probe (5′-TTTGAAGCCTGCACCCCAGA-3′) was subsequently used in the sensitized hybridization detection reaction (see Fig. 1). Both oligoDNA unfolder and oligoDNA probe were similarly constructed as in Buvoli et al. (2000) where the double-oligo hybridization signal was ≈100-fold greater than probe alone.

Dissociation rate constant measurements

Liposomes prepared from HeLa membrane lipids were reacted with total HeLa RNA in 20 μL and applied to a Sephacryl S-1000 Superfine column. The column was spun for 10 sec at 100g to place the liposomes within the column matrix. Then 100 μL of Buffer (C) was applied and the column was spun again for 30 sec at 100g to separate liposome–RNA (LR) complexes from unbound RNA molecules. We selected this method in preference to a similar dilution protocol because dilution would substantially reduce the tRNASec signal in the Northern blot. LR complexes were collected and 20 μL aliquots were loaded on a second Sephacryl column for separation of LR complexes from the unbound RNA. tRNASec bound to the liposomes in the dispersion was visualized using Northern blotting. The first-order dissociation rate constant, kdiss, was determined from [LR]t = [LR]o · exp(−kdiss · t), where [LR]t = concentration of tRNASec in complex with liposomes (normalized for the amount of liposomes) at time t, [LR]o = concentration of tRNASec in complex with liposomes at time 0, t = incubation time since the initial 10-sec spin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ada Buvoli and Dr. Massimo Buvoli (University of Colorado at Boulder), and Dr. Maja M. Janas (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) for advice on Northern blots, Dr. Steve Langer (University of Colorado at Boulder) for technical advice on growing HeLa cells, Deepa Puthenvedu (University of Colorado at Boulder) for running Western blots, and Dr. Norm Pace (University of Colorado at Boulder) for use of his NanoDrop spectrofluorometer. This research was supported in part by NIH R01GM30881.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.035352.112.

REFERENCES

- Burkard U, Söll D 1988. The unusually long amino acid acceptor stem of Escherichia coli selenocysteine tRNA results from abnormal cleavage by RNase P. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 1247–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvoli A, Buvoli M, Leinwand LA 2000. Enhanced detection of tRNA isoacceptors by combinatorial oligonucleotide hybridization. RNA 6: 912–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carell T, Brandmayr C, Hienzsch A, Muller M, Pearson D, Reiter V, Thoma I, Thumbs P, Wagner M 2012. Structure and function of noncanonical nucleobases. Angew Chem Int Ed 51: 7110–7131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluett EB, Machamer CE 1996. The envelope of vaccinia virus reveals an unusual phospholipid in Golgi complex membranes. J Cell Sci 109: 2121–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C, Sobala A, Lu C, Thatcher SR, Bowman A, Brown JWS, Green PJ, Barton GJ, Hutvagner G 2009. Filtering of deep sequencing data reveals the existence of abundant Dicer-dependent small RNAs derived from tRNAs. RNA 15: 2147–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras FX, Sot J, Alonso A, Goni FM 2006. Sphingosine increases the permeability of model and cell membranes. Biophys J 90: 4085–4092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers EE, Tijsen AJ, Pinto YM 2012. Circulating microRNAs: Novel biomarkers and extracellular communicators in cardiovascular disease? Circ Res 110: 481–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangoiti P, Camacho L, Arana L, Ouro A, Granada MH, Brizuela L, Casas J, Fabrias G, Abad JL, Delgado A, et al. 2010. Control of metabolism and signaling of simple bioactive sphingolipids: Implications in disease. Prog Lipid Res 49: 316–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovko A, Hjalm G, Sitbon F, Nicander B 2000. Cloning of a human tRNA isopentenyl transferase. Gene 258: 85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni FM, Alonso A 2006. Biophysics of sphingolipids I. Membrane properties of sphingosine, ceramides and other simple sphingolipids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1758: 1902–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA, Obeid LM 2008. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: Lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst JA, Guilford JM, Fox TE, Wang X, Conroy EJ, Yun JK 2009. Sphingosine kinase 1 localized to the plasma membrane lipid raft microdomain overcomes serum deprivation induced growth inhibition. Arch Biochem Biophys 492: 62–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Chiba S, Sekine S, Yokoyama S 2009. Crystal structure of human selenocysteine tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 6259–6268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas T, Yarus M 2003. Visualization of membrane RNAs. RNA 9: 1353–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas T, Janas T, Yarus M 2004. A membrane transporter for tryptophan composed of RNA. RNA 10: 1541–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas T, Janas T, Yarus M 2005. RNA, lipids and membranes. In The RNA World III (ed. R Gesteland et al.), pp. 207–225. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- Janas T, Janas T, Yarus M 2006. Specific RNA binding to ordered phospholipid bilayers. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 2128–2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas T, Widmann JJ, Knight R, Yarus M 2010. Simple, recurrent RNA binding sites for L-arginine. RNA 16: 805–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas T, Nowotarski K, Janas T 2011. The effect of long-chain bases on polysialic acid-mediated membrane interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808: 2322–2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LY, Yue ST, Cheung CY, Singer VL 1998. RNA quantitation by fluorescence based solution assay: RiboGreen reagent characterization. Anal Biochem 265: 368–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato N, Hoshino H, Harada F 1983. Minor serine tRNA containing anticodon NCA (C4 RNA) from human and mouse cells. Biochem Int 7: 635–645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova A, Kwak YG, Tamkun M, Majerfeld I, Yarus M 1999. RNAs that bind and change the permeability of phospholipid membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 10649–10654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R, Birmingham A, Yarus M 2004. BayesFold: Rational secondary folds that combine thermodynamic, covariation, and chemical data for aligned RNA sequences. RNA 10: 1323–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levental I, Grzybek M, Simons K 2011. Raft domains of variable properties and compositions in plasma membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 11411–11416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loya A, Pnueli L, Yosefzon Y, Wexler Y, Ziv-Ukelson M, Arava Y 2008. The 3′-UTR mediates the cellular localization of an mRNA encoding a short plasma membrane protein. RNA 14: 1352–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechler BM 1987. Isolation of messenger RNA from membrane-bound polysomes. Methods Enzymol 152: 241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczak A, Srivastava RA, Apirion D 1991. Location of the RNA processing enzymes RNase III. RNase E and RNase P in the Escherichia coli cell. Mol Microbiol 5: 1801–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JF, Uhlenbeck OC 1989. Synthesis of small RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol 180: 51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D, Ben-Tal N, Honig B, McLaughlin S 1997. Electrostatic interaction of myristoylated proteins with membranes: Simple physics, complicated biology. Structure 5: 985–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo-Dinur K, Nussbaum-Shochat A, Ben-Yehuda S, Amster-Choder O 2011. Translation-independent localization of mRNA in E. coli. Science 331: 1081–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palioura S, Sherrer RL, Steitz TA, Söll D, Simonović M 2009. The human SepSecS-tRNASec complex reveals the mechanism of selenocysteine formation. Science 325: 321–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson T 2010. Regulatory RNAs derived from transfer RNA? RNA 16: 1865–1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PJ 2010. A lipid matrix model of membrane raft structure. Prog Lipid Res 49: 390–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan A, Goldstein JL, McDonald JG, Brown MS 2008. Switch-like control of SREBP-2 transport triggered by small changes in ER cholesterol: A delicate balance. Cell Metab 8: 512–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raouane M, Desmaële D, Urbinati G, Massaad-Massade L, Couvreur P 2012. Lipid conjugated oligonucleotides: A useful strategy for delivery. Bioconjug Chem 23: 1091–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD 2006. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat Chem Biol 2: 584–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K, Gerl MJ 2010. Revitalizing membrane rafts: New tools and insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 688–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Hu W, Xu R, Jin J, Szulc ZM, Zhang G, Galadari SH, Obeid LM, Mao C 2009. Alkaline ceramidase 2 regulates β1 integrin maturation and cell adhesion. FASEB J 23: 656–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsecchi M, Chigorno V, Nicolini M, Sonnino S 1996. Changes of free long-chain bases in neuronal cells during differentiation and aging in culture. J Neurochem 67: 1866–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vankin D 2003. Structure−function relations in self-assembled C18- and C20-sphingosines monolayers at gas/water interfaces. J Am Chem Soc 125: 1313–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT 2011. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol 13: 423–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassov A, Khvorova A, Yarus M 2001. Binding and disruption of phospholipid bilayers by supramolecular RNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 7706–7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise K, Triola G, Janosch S, Waldmann H, Winter R 2010. Visualizing association of lipidated signaling proteins in heterogeneous membranes-partitioning into subdomains, lipid sorting, interfacial adsorption, and protein association. Biochim Biophys Acta 1798: 1409–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AB, Givogri MI, Lopez-Rosas A, Cao H, van Breemen R, Thinakaran G, Bongarzone ER 2009. Psychosine accumulates in membrane microdomains in the brain of Krabbe patients, disrupting the raft architecture. J Neurosci 29: 6068–6077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Jin J, Hu W, Sun W, Bielawski J, Szulc Z, Taha T, Obeid LM, Mao C 2006. Golgi alkaline ceramidase regulates cell proliferation and survival by controlling levels of sphingosine and S1P. FASEB J 20: 1813–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagitani K, Imagawa Y, Iwawaki T, Hosoda A, Saito M, Kimata Y, Kohno K 2009. Cotranslational targeting of XBP1 protein to the membrane promotes cytoplasmic splicing of its own mRNA. Mol Cell 34: 191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihisa T, Yunoki-Esaki K, Ohshima C, Tanaka N, Endo T 2003. Possibility of cytoplasmic pre-tRNA splicing: The yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease mainly localizes on the mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell 14: 3266–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, O'Donoghue P, Ambrogelly A, Gundllapalli S, Sherrer RL, Palioura S, Simonović M, Söll D 2010. Distinct genetic code expansion strategies for selenocysteine and pyrrolysine are reflected in different aminoacyl-tRNA formation systems. FEBS Lett 584: 342–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Huang RH 2008. Crystallographic snapshots of eukaryotic dimethylallyltransferase acting on tRNA: Insight into tRNA recognition and reaction mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 16142–16147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]