Background: Phosphatidate phosphatase (PAP) plays diverse roles in lipid metabolism and cell signaling.

Results: A novel yeast PAP is identified as the actin patch protein encoded by APP1.

Conclusion: APP1 and other known genes (PAH1, DPP1, LPP1) are responsible for all detectable PAP activity in yeast.

Significance: Identification of App1p as a PAP enzyme will facilitate the understanding of its cellular function.

Keywords: Diacylglycerol, Lipids, Lipid Metabolism, Phosphatase, Phosphatidate, Phospholipid, Phospholipid Metabolism

Abstract

Phosphatidate phosphatase (PAP) catalyzes the dephosphorylation of phosphatidate to yield diacylglycerol. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PAP is encoded by PAH1, DPP1, and LPP1. The presence of PAP activity in the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant indicated another gene(s) encoding the enzyme. We purified PAP from the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant by salt extraction of mitochondria followed by chromatography with DE52, Affi-Gel Blue, phenyl-Sepharose, MonoQ, and Superdex 200. Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis of a PAP-enriched sample revealed multiple putative phosphatases. By analysis of PAP activity in mutants lacking each of the proteins, we found that APP1, a gene whose molecular function has been unknown, confers ∼30% PAP activity of wild type cells. The overexpression of APP1 in the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutant exhibited a 10-fold increase in PAP activity. The PAP activity shown by App1p heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli confirmed that APP1 is the structural gene for the enzyme. Introduction of the app1Δ mutation into the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant resulted in a complete loss of PAP activity, indicating that distinct PAP enzymes in S. cerevisiae are encoded by APP1, PAH1, DPP1, and LPP1. Lipid analysis of cells lacking the PAP genes, singly or in combination, showed that Pah1p is the only PAP involved in the synthesis of triacylglycerol as well as in the regulation of phospholipid synthesis. App1p, which shows interactions with endocytic proteins, may play a role in vesicular trafficking through its PAP activity.

Introduction

PAP2 catalyzes the dephosphorylation of PA to produce DAG and Pi (1). The product DAG is utilized for the synthesis of the neutral storage lipid TAG and for the synthesis of the phospholipids phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine via the Kennedy pathway (1–6). The substrate PA is utilized for the synthesis of phospholipids (e.g. phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylglycerol, and cardiolipin) via the liponucleotide intermediate CDP-DAG (7–9). In addition to serving as intermediates in lipid synthesis, PA and DAG are involved in lipid signaling. For example, PA plays a role in cell growth activation, membrane proliferation, the transcription of lipid synthesis genes, secretion, and vesicular transport, whereas DAG activates protein kinase C (10–20). Thus, by the nature of its reaction, PAP activity may regulate the proportional synthesis of phospholipids and TAG, the pathways by which phospholipids are synthesized, and control the abundance of important signaling lipids. Indeed, biochemical and genetic studies using yeast and mammalian experimental systems have shown that PAP is an important regulator of lipid homeostasis and cell physiology (21–25).

Our laboratory has utilized the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model eukaryote to study the enzymology and physiological roles of PAP enzymes (22, 26). In S. cerevisiae, PAP is known to be encoded by three genes, namely PAH1 (27), DPP1 (28), and LPP1 (29). Pah1p PAP is a Mg2+-dependent enzyme whose reaction is based on the DXDX(T/V) catalytic motif within the haloacid dehalogenase-like domain of the enzyme (27, 30). In contrast, the PAP activities of Dpp1p (28) and Lpp1p (29) do not have a divalent cation requirement, and their reactions are based on a three-domain lipid phosphatase motif composed of the consensus sequences KX6RP, PSGH, and SRX5HX3D (31, 32). The Pah1p enzyme is specific for PA (27), whereas the Dpp1p and Lpp1p enzymes utilize PA and other lipid phosphate molecules (e.g. DAG pyrophosphate and lysoPA) as substrates (28, 29, 33–36). The PAP activities in yeast also differ with respect to their cellular locations and modes of regulation. Pah1p is found in the cytosol as a phosphoprotein that is a consequence of multiple phosphorylations (37–40). For catalysis, the phosphorylated enzyme translocates to the nuclear/endoplasmic reticulum membrane through its dephosphorylation (38, 41–43). Dpp1p (28, 44, 45) and Lpp1p (29, 46) are integral membrane enzymes with six transmembrane-spanning regions that are localized to the vacuole and Golgi compartments, respectively, of the cell.

Pah1p PAP plays an important role in lipid metabolism by controlling the relative proportions of PA and DAG (27, 47). An imbalance of these intermediates due to a loss of PAP activity results in cellular abnormalities that include a drastic reduction in TAG abundance and susceptibility to fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity, the misregulation of phospholipid synthesis and an aberrant expansion of the nuclear/endoplasmic reticulum membrane, and defects in lipid droplet formation and vacuole homeostasis (27, 30, 43, 47–49). The Dpp1p and Lpp1p are not involved in de novo lipid synthesis that occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum (21, 28, 29). Instead, these enzymes are thought to have roles in lipid signaling by controlling the amounts of PA, DAG pyrophosphate, and lysoPA in the organelles where they reside (21, 26).

A significant amount of Mg2+-dependent PAP activity is still present in the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant (27). However, unlike Pah1p PAP, this activity is sensitive to inhibition by N-ethylmaleimide (27). The enzyme activity is found in both the cytosolic and the membrane fractions of the cell, and its association with the membrane is peripheral in nature (27). Studies to gain insight into the physiological role of the PAP activity have been hampered because the gene encoding the enzyme has yet to be identified. In this work, we purified PAP from the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant and identified APP1 as the gene encoding the enzyme. The lack of detectable PAP activity in the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ quadruple mutant indicated that all PAP activity in yeast is encoded by APP1, PAH1, DPP1, and LPP1. Moreover, this work identified the molecular function of the actin patch protein App1p as a PAP enzyme.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All chemicals were reagent grade. Growth medium supplies were purchased from Difco. Polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection kit, phenyl-Sepharose CL-4B, MonoQ, and Superdex 200 columns were purchased from GE Healthcare. DE52 (DEAE-cellulose) was purchased from Whatman. Affi-Gel Blue, protein assay reagents, electrophoretic reagents, and protein standards were purchased from Bio-Rad. Radiochemicals were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Bovine serum albumin, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, benzamidine, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside, sodium cholate, and Triton X-100 were purchased from Sigma. Lipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. Silica gel thin-layer chromatography plates were from EM Science. Restriction endonucleases, modifying enzymes, and recombinant VentR DNA polymerase were purchased from New England Biolabs. Plasmid isolation and gel extraction kits and Ni2+-NTA-agarose resin were purchased from Qiagen. Invitrogen was the source of the DNA size standards and the yeast deletion consortium strain collection. The Yeast Maker yeast transformation kit was purchased from Clontech. Stratagene supplied the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. Nourseothricin (LEXSY NTC) was purchased from Jena Bioscience. Mouse monoclonal anti-HA, and anti-His6 antibodies were from Roche Applied Science. Anti-App1p antibodies were prepared in rabbits against the C-terminal portion (residues 490–502) of the protein at EZBiolab. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies were from Thermo Scientific and Pierce, respectively. Scintillation counting supplies were purchased from National Diagnostics.

Strains and Growth Conditions

The strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were grown in YEPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or in synthetic complete medium containing 2% glucose at 30 °C as described previously (50, 51). For selection of yeast cells bearing plasmids, the appropriate amino acids were omitted from synthetic complete medium. Plasmid maintenance/amplifications (strain DH5α) and App1p expression (strain BL21(DE3)pLysS) were performed in Escherichia coli. The bacterial cells were grown in LB medium (1% Tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, pH 7.4) at 37 °C, and ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was added to select for the cells carrying plasmid. For growth on solid media, agar plates were prepared with supplementation of either 2% (yeast) or 1.5% (E. coli) agar. For App1p PAP purification in yeast, pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutant cells were grown to late exponential phase in YEPD medium at 30 °C. For heterologous expression of His6-tagged App1p, E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells bearing pMC101 were grown to A600 nm = 0.5 at 30 °C in 1 liter of LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml). The culture was then incubated for 3 h with 1 mm isopropyl-B-d-thiogalactoside to induce the expression of the PAP enzyme.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ (lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) phoA supE44 l−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Ref. 51 |

| BL21(DE3)pLysS | F− ompT hsdSB (rB−mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS | Novagen |

| S. cerevisiae strains | ||

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Ref. 109 |

| BY4741-app1Δ | app1Δ::kanMX4 derivative of BY4741 | Deletion consortium |

| W303–1A | MATa ade2–1 can1–100 his3–11,15 leu2–3,112 trp1–1 ura3–1 | Ref. 110 |

| GHY63 | app1Δ::natMX4 derivative of W303–1A | This study |

| GHY57 | pah1Δ::URA3 derivative of W303–1A | Ref. 27 |

| GHY64 | app1Δ::natMX4 pah1Δ::URA3 derivative of W303–1A | This study |

| TBY1 | dpp1Δ::TRP1/Kanr lpp1Δ::HIS3/Kanr derivative of W303–1A | Ref. 29 |

| GHY65 | app1Δ::natMX4 dpp1Δ::TRP1/Kanr lpp1Δ::HIS3/Kanr derivative of W303–1A | This study |

| GHY58 | pah1Δ::URA3 dpp1Δ::TRP1/Kanr lpp1Δ::HIS3/Kanr derivative of W303–1A | Ref. 27 |

| GHY66 | app1Δ::natMX4 pah1Δ::URA3 dpp1Δ::TRP1/Kanr lpp1Δ::HIS3/Kanr derivative of W303–1A | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| YEp351 | Multicopy E. coli/yeast shuttle vector with LEU2 | Ref. 91 |

| pMC102 | APP1 gene inserted into YEp351 | This study |

| pMC102-D281E | APP1 (D281E) derivative of pMC102 | This study |

| pMC103 | APP1HA gene inserted into YEp351 | This study |

| pMC103-D281E | APP1 (D281E) derivative of pMC103 | This study |

| pET-15b | E. coli expression vector with N-terminal His6 tag fusion | Novagen |

| pMC101 | APP1 coding sequence inserted into pET-15b | This study |

DNA Manipulations, Cloning of APP1, and Construction of Plasmids

Standard methods were used to isolate plasmid and genomic DNA and for manipulation of DNA using restriction enzymes, DNA ligase, and modifying enzymes (51). Transformations of S. cerevisiae (52) and E. coli (51) with DNA/plasmids and PCR reactions (53) followed the standard protocols. The plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. The S. cerevisiae APP1 gene was cloned by PCR. A 3,024-bp DNA fragment that contains the entire coding sequence (1,764 bp) of APP1, the 5′-untranslated region (824 bp), and the 3′-untranslated region (436 bp) was amplified from W303-1A genomic DNA (forward, 5′-GATTATAAGCTTAACTGACACCCATATCGCTTGACCC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTCAATATACGTGCATCTAGAAGGCCTTTCCCGAC-3′). The APP1 DNA fragment was digested with HindIII/XbaI and inserted into plasmid YEp351 at the same restriction enzyme sites. The multicopy plasmid containing APP1 was named pMC102. The APP1 gene was used to construct APP1HA, in which the sequence for the HA epitope (YPYDVPDYA) was located after the start codon. The 854-bp (forward, 5′-GATTATAAGCTTAACTGACACCCATATCGCTTGACCC-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTACATCTTTTTATTCCTTCTCCAAAGCAATTTTTTCCCCC-3′) and 2,224-bp (forward, 5-TACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCTAATAGTCAAGGTTACGATGAAAGCTCTTCCTCTACTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTCAATATACGTGCATCTAGAAGGCCTTTCCCGAC-3′) APP1 DNA fragments that contain the HA tag at the 3′ and 5′ ends, respectively, were amplified by PCR. These PCR products containing 27-bp overlapping ends were combined by overlap extension PCR. The combined 3,051-bp DNA was then amplified, digested with HindIII and XbaI, and inserted into YEp351 at HindIII/XbaI sites. The multicopy plasmid containing APP1HA was named pMC103. Plasmids pMC102-D281E and pMC103-D281E were produced by PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis with the codon change of GAT to GAA. The nucleotide change in the APP1 and APP1HA alleles was confirmed by DNA sequencing. For expression of APP1 in E. coli, its coding sequence (except the first nucleotide) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA template (forward, 5′-TGAATAGTCAAGGTTACGATGAAAGCTCTTCC-3′; reverse, 5′-TAATCCTCGAGTTAGTTTGAATACTTCTCCCTAATTCTGCG-3′). The 1,774-bp PCR product was digested with XhoI, and the vector pET-15b was digested with NdeI, filled with Klenow, and digested with XhoI. The blunt cohesive end PCR products were inserted into pET-15b at NdeI (Klenow)/XhoI sites. The plasmid bearing His6-tagged APP1 was named pMC101.

Construction of the app1Δ Mutant and Its Derivatives

The app1Δ mutation in the wild type strain W303-1A and in the dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutant strain TBY1 was generated by one-step gene replacement (54). The strains were transformed with the 1,219-bp disruption cassette (app1Δ::natMX4) that had been amplified from pAG25 (EUROSCARF) (forward, 5′-AGTTCCGTCAAAGGGGGAAAAAATTGCTTTGGAGAAGGAATAAAAAGATGACATGGAGGCCCAGAATACCC-3′; reverse, 5′-TATACAATTTTTAAACTCCCTCCCGATGTATATAAATAACAGTGTATTTACAGTATAGCGACCAGCATTCAC-3′). Yeast transformants were selected on YEPD medium containing 100 μg/ml nourseothricin, and the app1Δ mutation in the nourseothricin-resistant cells was confirmed by PCR amplification of the 1,217-bp fragment from genomic DNA (forward, 5′-AGGGGGAAAAAATTGCTTTGGA-3′; reverse, 5′-ATACAATTTTTAAACTCCCTCCCG-3′). The pah1Δ mutation in the app1Δ mutant strain GHY63 and the app1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutant strain GHY65 was generated by one-step gene replacement as described previously (27).

Partial Purification of App1p PAP from S. cerevisiae

The pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutant strain GHY58 (27) was used to purify PAP activity that is not encoded by the PAH1 (27), DPP1 (28), or LPP1 (29) gene. All steps were performed at 8 °C.

Step 1: Preparation of Cell Extract

The pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant cells were harvested in the late exponential phase, and cells were resuspended in buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.3 m sucrose, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mm Na2EDTA, 0.5 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm benzamide, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin). Cells (200 g, wet weight) were disrupted with glass beads (0.5-mm diameter) using a Biospec Products BeadBeater as described previously (55). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells and glass beads. Protein concentration was estimated by the method of Bradford (56) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Step 2: Preparation of Crude Mitochondria

Crude mitochondria were collected from the cell extract by centrifugation at 32,000 × g for 10 min (57).

Step 3: Preparation of NaCl Extract

Mitochondria were suspended in buffer A containing 1 m NaCl to a final protein concentration of 10 mg/ml. The suspension was centrifuged at 32,000 × g for 10 min to remove salt-unextractable proteins from mitochondrial membranes. The supernatant containing the salt-extracted proteins was then dialyzed overnight against buffer B (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 0.5% sodium cholate. Sodium cholate was added to buffer B to prevent the precipitation of PAP that occurred after the removal of salt from the enzyme preparation.

Step 4: DE52 Chromatography

A DE52 column (1.5 × 7 cm) was equilibrated with buffer B containing 0.5% sodium cholate. The enzyme preparation from the previous step was applied to the column at a flow rate of 40 ml/h, and the column was washed with 5 column volumes of buffer B plus 0.5% sodium cholate followed by elution of the enzyme in 5-ml fractions with 10 column volumes of a linear NaCl gradient (0–0.5 m) in the same buffer. The peak of PAP activity eluted at 0.2 m NaCl.

Step 5: Affi-Gel Blue Chromatography

An Affi-Gel blue column (1.5 × 5 cm) was equilibrated with buffer B containing 0.5% sodium cholate and 0.2 m NaCl. The DE52-purified enzyme was applied to the column at a flow rate of 60 ml/h. The column was washed with 5 column volumes of buffer B containing 0.5% sodium cholate and 0.5 m NaCl. PAP activity was then eluted in 3-ml fractions with 12 column volumes of a linear gradient of NaCl (0.5–3.0 m) in buffer B containing 0.2% sodium cholate. The peak of activity eluted at a NaCl concentration of 1.3 m.

Step 6: Phenyl-Sepharose Chromatography

A phenyl-Sepharose (0.8 × 2 cm) column was equilibrated with buffer B containing 0.2% sodium cholate and 3 m NaCl. The Affi-Gel Blue-purified enzyme was made to contain 3 m NaCl and then applied to the column under gravity flow. The column was first washed with 10 column volumes of the equilibration buffer and then washed with 10 column volumes of the buffer without NaCl. PAP activity was then eluted in 1-ml fractions with 1% Triton X-100 in buffer B. Hereafter, the PAP activity was made soluble with Triton X-100 instead of sodium cholate.

Step 7: MonoQ Chromatography

A MonoQ column (0.5 × 5 cm) was equilibrated with buffer B containing 0.5% Triton X-100. The phenyl-Sepharose-purified enzyme was applied to the column; the column was then washed with 5 column volumes of buffer B containing 0.5% Triton X-100 followed by elution of PAP in 1-ml fractions with 20 column volumes of a linear NaCl gradient (0–1 m) at a flow rate 24 ml/h. The peak of activity was eluted at NaCl concentration of 0.5 m.

Step 8: Superdex 200 Chromatography

A gel filtration Superdex 200 column (1 × 30 cm) was equilibrated with buffer C containing 0.5 m NaCl and 0.5% Triton X-100. The MonoQ-purified enzyme was applied to the column at a flow rate of 40 ml/h. The enzyme was then eluted in 0.5-ml fractions with 1 column volume of the same buffer.

Purification of His6-tagged App1p PAP from E. coli

All steps were performed at 8 °C. E. coli cells expressing His6-tagged App1p were suspended in 20 ml of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 0.5 m NaCl, 5 mm imidazole, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cells were disrupted by a freeze-thawing cycle and by two passes through a French press at 20,000 p.s.i. Unbroken cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (cell lysate) was gently mixed with 2 ml of 50% slurry of Ni2+-NTA-agarose for 2 h. The Ni2+-NTA-agarose/enzyme mixture was packed in a 10-ml column and washed with 20 ml of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 0.5 m NaCl, 45 mm imidazole, 10% glycerol, and 7 mm 2-mercaptoethanol. His6-tagged App1p was eluted from the column in 1-ml fractions with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 0.5 m NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, 10% glycerol, and 7 mm 2-mercaptoethanol. Purified enzyme preparations were stored at −80 °C.

PAP Assay

PAP activity was measured for 20 min by following the release of water-soluble [32P]Pi from chloroform-soluble [32P]PA (5,000 cpm/nmol) at 30 °C as described previously (58). The [32P]PA substrate was synthesized enzymatically from DAG and [γ-32P]ATP with E. coli DAG kinase (58). The reaction mixture contained 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm PA, 2 mm Triton X-100, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and enzyme protein in a total volume of 0.1 ml. Enzyme assays were conducted in triplicate, and the average standard deviation of the assays was ± 5%. All reactions were linear with time and protein concentration. A unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the formation of 1 nmol of product per minute.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

SDS-PAGE (59) using 10% slab gels and Western blotting (60, 61) using polyvinylidene difluoride membrane were performed as described previously. Proteins in polyacrylamide gels were visualized by staining with Coomassie Blue R250. The anti-HA, anti-His6, and anti-App1p antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:500, 1:5000, and 1:5000, respectively. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies and goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:5,000. Immune complexes were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection kit. Fluorimaging was used to acquire images from Western blots.

Identification of Proteins by Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry

An SDS-polyacrylamide gel slice containing proteins purified through the Superdex 200 chromatography step was subjected to trypsin digestion (62) followed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry using a Thermo Fisher Scientific LTQ Orbitrap Velos instrument (63). The spectra were searched against the Swiss-Prot yeast database using the MASCOT (V.2.3) search engine (62). This work was performed at the Center for Advanced Proteomics Research facility of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (Newark, NJ).

Labeling and Analysis of Lipids

Steady-state labeling of phospholipids and neutral lipids with [32P]Pi and [2-14C]acetate, respectively, was performed as described previously (27). Lipids were extracted from labeled cells by the method of Bligh and Dyer (64). Phospholipids were analyzed by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates using chloroform/methanol/ammonium hydroxide/water (45:25:2:3, v/v) as the solvent system for dimension one and chloroform/methanol/glacial acetic acid/water (32:4:5:1, v/v) as the solvent system for dimension two (65). Neutral lipids were analyzed by one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates using the solvent system hexane/diethyl ether/glacial acetic acid (40:10:1, v/v) (66). The identity of the labeled lipids on TLC plates was confirmed by comparison with standards after exposure to iodine vapor. Radiolabeled lipids were visualized by phosphorimaging analysis. The relative quantities of labeled lipids were analyzed using ImageQuant software.

Analyses of Data

Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaPlot software. The p values < 0.05 were taken as a significant difference.

RESULTS

PAP Activity in the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ Triple Mutant Is Encoded by the APP1 Gene

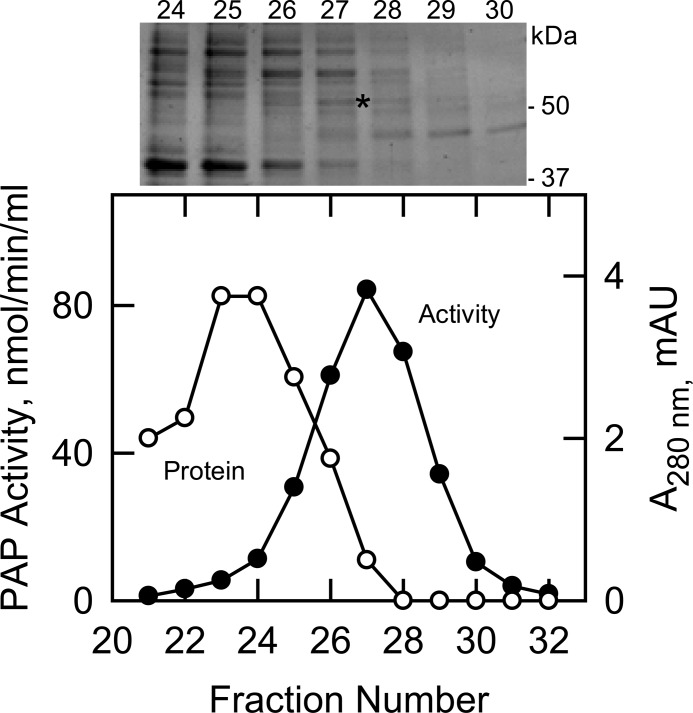

The pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant, which does not contain PAP encoded by known genes (i.e. PAH1, DPP1, and LPP1), was used to purify the unknown PAP enzyme. The PAP activity in the triple mutant was associated with the cytosolic (0.7 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg), microsomal (1 ± 0.1 nmol/min/mg), and mitochondrial (5 ± 0.3 nmol/min/mg) fractions. The PAP specific activity was enriched 5-fold in the mitochondrial fraction over the cell extract, and accordingly, this fraction was used as the source of enzyme. PAP activity was dissociated from mitochondrial membranes with 1 m NaCl followed by dialysis for desalting and chromatography with DE52, Affi-Gel Blue, phenyl-Sepharose, MonoQ, and Superdex 200. We noted the precipitation of PAP activity upon the removal of salt, and thus, sodium cholate or Triton X-100 was included in the chromatography buffers to maintain its solubility. The presence of salt also stabilized PAP activity. The Superdex 200 step afforded the greatest enrichment (4.5-fold) in specific activity (Table 2). The elution profiles of PAP activity and protein and an SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that the enzyme preparation was not pure (Fig. 1). Attempts to further purify the enzyme were unsuccessful because the PAP activity was labile. Overall, the enzyme was purified 2,143-fold over the cell extract to a final specific activity of 1,500 nmol/min/mg with an activity yield of 5% (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Partial purification of App1p PAP from S. cerevisiae

PAP was purified from pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutant cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are based on starting with 200 g (wet weight) of cells.

| Purification step | Total units | Protein | Specific activity | Yield | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol/min | mg | units/mg | % | -fold | |

| Cell extract | 3,237 | 4,625 | 0.7 | 100 | 1 |

| Mitochondria | 2,200 | 628 | 3.5 | 68 | 5 |

| NaCl extract | 1,745 | 346 | 5 | 54 | 7 |

| DE52 | 1,053 | 65 | 16 | 33 | 23 |

| Affi-Gel Blue | 770 | 20 | 39 | 24 | 56 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose | 545 | 4 | 137 | 17 | 196 |

| MonoQ | 300 | 0.9 | 330 | 9 | 471 |

| Superdex 200 | 150 | 0.1 | 1,500 | 5 | 2,143 |

FIGURE 1.

Elution profiles of PAP activity and protein after chromatography with Superdex 200 and SDS-PAGE of the purified enzyme. The MonoQ-purified PAP enzyme preparation was subjected to chromatography with Superdex 200. Fractions were collected and assayed for PAP activity (●) and protein (○). Fractions 24–30 were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Blue (above plot). The positions of electrophoresis molecular mass standards are indicated in the figure. The band derived from fraction 27 that was used for protein sequencing is indicated by the asterisk. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

The peak of PAP activity that emerged from the Superdex 200 column correlated with the enrichment of a minor protein band that migrated just above the size of the 50-kDa molecular mass marker (Fig. 1, fraction 27, indicated by the asterisk). An SDS-polyacrylamide gel slice containing this band was subjected to trypsin digestion followed by the analysis of peptides by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. This analysis yielded a few proteins of unknown function that upon further analysis (e.g. expression and purification in E. coli) showed no PAP activity. This indicated that the PAP enzyme in the preparation was very low in abundance. Accordingly, we used more sensitive liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to detect low abundance proteins. This analysis revealed that the enzyme preparation contained 112 proteins (or proteolytic fragments thereof). From the list, we focused on those proteins with unknown molecular function that possessed a phosphatase motif. We also considered proteins that are thought to be involved in phospholipid synthesis. Based on these criteria, we analyzed cell extracts from 20 mutants from the yeast deletion strain collection for a loss in PAP activity. Of the mutants, only app1Δ exhibited a 30% decrease in PAP activity when compared with the wild type parental strain. These data indicated that the PAP activity might be directed by the APP1 gene.

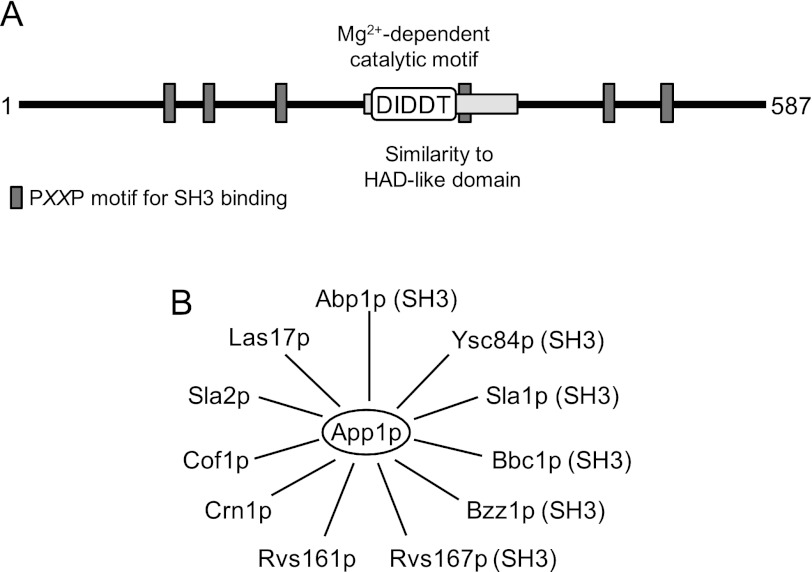

The acronym APP1 stands for actin patch protein (67) because App1p is a component of cortical actin patches and interacts with endocytic proteins (67–75) (Fig. 2). Pfam analysis indicated that App1p consisting of 587 amino acids in length (66.1 kDa) contains a region with weak sequence similarity to a haloacid dehalogenase-like domain (76) (Fig. 2). Contained within this domain is a DXDX(T/V) (residues 281–285) catalytic motif that is present in the superfamily of Mg2+-dependent phosphatase enzymes (77) that include yeast Pah1p and mammalian lipin PAP enzymes (27, 78). App1p also contains several PXXP motifs (Fig. 2) that are important for interactions with proteins that possess SH3 domains (79, 80).

FIGURE 2.

Motifs in App1p and its interacting endocytic cortical actin patch proteins. A, the diagram shows a linear representation of App1p with the approximate positions of the region that has similarity to a haloacid dehalogenase (HAD)-like domain (76), the DXDX(T/V) catalytic motif, and the PXXP motif for SH3 binding. B, the diagram shows that App1p interacts with the endocytic proteins Abp1p (69–73), Bbc1p (70, 73), Bzz1p (70, 73, 74), Cof1p (69), Crn1p (67), Las17p (75), Rvs161p (67, 68, 70, 73, 74), Rvs167p (67, 68, 70, 73, 74), Sla1p (67, 73), Sla2p (67), and Ysc84p (70, 73). The proteins that possess SH3 binding domains are indicated by the parentheses after the name.

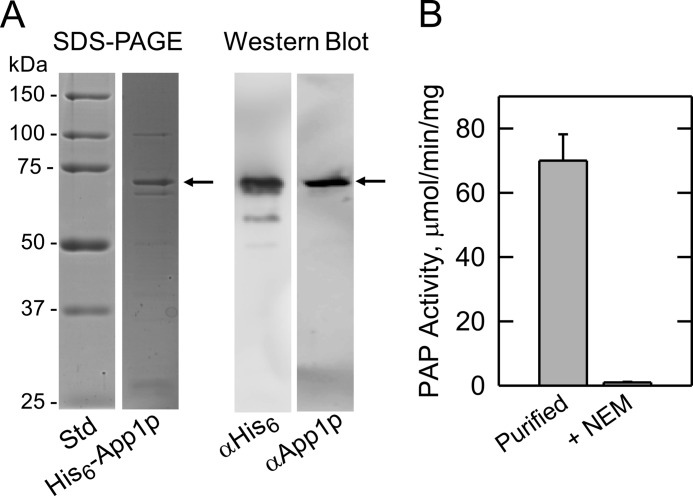

To prove that APP1 encodes PAP, we used heterologous overexpression of APP1 in E. coli. The S. cerevisiae APP1 coding sequence was amplified by PCR and inserted into plasmid pET-15b for the isopropyl-B-d-thiogalactoside-inducible expression of His6-tagged protein. The purified His6-tagged App1p migrated upon SDS-PAGE at the expected size of ∼68 kDa (Fig. 3A). In addition, the purified protein was confirmed by immune reaction with antibodies directed against the His6 epitope and against a peptide sequence found at the C-terminal portion of App1p (Fig. 3A). The purified protein catalyzed the Mg2+-dependent PAP reaction, and the addition of 10 mm Na2EDTA abolished PAP activity. Unlike the Mg2+-dependent Pah1p PAP, App1p enzyme activity was sensitive to inhibition by N-ethylmaleimide (Fig. 3B). That App1p expressed in E. coli exhibits PAP activity also indicated that a posttranslational modification that might occur in yeast is not essential for enzyme activity.

FIGURE 3.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of His6-tagged App1p purified from E. coli and the PAP activity of the purified enzyme. A, molecular mass standards (Std) and His6-tagged App1p (1 μg) purified from E. coli were subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue (left). The purified His6-tagged App1p (samples of 1 μg and 1 ng, respectively) was subjected to Western blot analysis using a 1:5000 dilution of anti-His6 (αHis6) and anti-App1p (αApp1p) antibodies, respectively (right). B, PAP activity of purified His6-tagged App1p measured in the absence and presence of 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). The data in A were representative of two experiments, whereas the data in B were the average of three experiments ± S.D. (error bars).

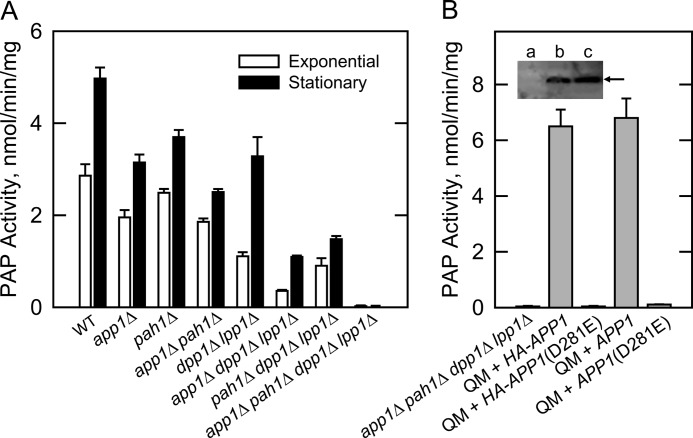

PAP Activity Is Affected by the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ Mutations and by the APP1(D281E) Mutation

We constructed a variety of isogenic mutants where the app1Δ mutation was combined with mutations of the other PAP genes in S. cerevisiae (Table 1). In this manner, we could determine the contribution of APP1 and the other PAP genes to the total PAP activity in yeast. In wild type cells, PAP activity is known to increase in the stationary phase of growth (81), and accordingly, the effect of the mutations was examined in both exponential and stationary phase cells (Fig. 4A). The APP1 gene accounted for 32 and 37% of the PAP activity in cell extracts of exponential and stationary phase cells, respectively. The PAH1-encoded enzyme accounted for 11 and 24% of the PAP activity in exponential and stationary phases, respectively. In the exponential phase, DPP1 and LPP1 accounted for 60% of the total PAP activity. A comparison of the activities from app1Δ pah1Δ and dpp1Δ lpp1Δ double mutants and from the app1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ and pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutants indicated that APP1 and PAH1 were primarily responsible for the induced expression of PAP activity in the stationary phase. The induced expression of DPP1-encoded PAP activity in stationary phase cells is governed by inositol (82), a phospholipid precursor that was not supplemented to the growth medium in this work. Finally, the lack of detectable PAP activity in the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ quadruple mutant indicated that all PAP activity (i.e. Mg2+-dependent and Mg2+-independent) in S. cerevisiae was attributed to APP1, PAH1, DPP1, and LPP1 (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of the app1Δ mutation, APP1 overexpression, and APP1(D281E) mutation on PAP activity. A, PAP activity was measured in cell extracts prepared from the indicated mutants grown to the exponential and stationary phases of growth. B, cell extracts were prepared from the indicated cells at the exponential phase of growth and assayed for PAP activity. Inset, samples (50 μg protein) of the cell extracts were subjected to Western blot using a 1:500 dilution of anti-HA antibodies. Lanes a, b, and c correspond to the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ quadruple mutant (QM), and the QM mutant overexpressing HA-APP1 and HA-APP1(D281E), respectively. The arrow indicates the position of HA-tagged App1p. The activity data shown in A and B were the average of three experiments ± S.D. (error bars), whereas the Western blot shown in B is representative of three experiments.

APP1 and HA-APP1 versions were expressed on a multicopy plasmid in the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ quadruple mutant, and cell extracts were prepared for the measurement of PAP activity. The PAP-deficient mutant expressing these genes exhibited PAP activities of 6.8 ± 0.7 and 6.5 ± 0.6 nmol/min/mg, respectively (Fig. 4B). This corresponded to about a 10-fold overproduction of activity when compared with that found in the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant (Fig. 4A). That both versions of APP1 directed the same level of activity indicated that the HA epitope did not compromise enzyme activity. The first conserved aspartate residue in the DIDDT sequence in App1p was mutated to glutamate by site-specific mutagenesis. Glutamate was chosen to replace aspartate to conserve the charge of the amino acid at this position, and thus, minimize a structural change in the enzyme. The D281E mutation abolished the overexpressed PAP activity directed by the APP1 and HA-APP1 genes (Fig. 4B). An immunoblot analysis using anti-HA antibodies showed that the D281E mutation in the HA-tagged version of App1p did not affect the expression of the enzyme (Fig. 4B, inset). These data indicated that the DIDDT sequence in App1p is responsible for its PAP catalytic function.

Effects of the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ Mutations on Lipid Composition

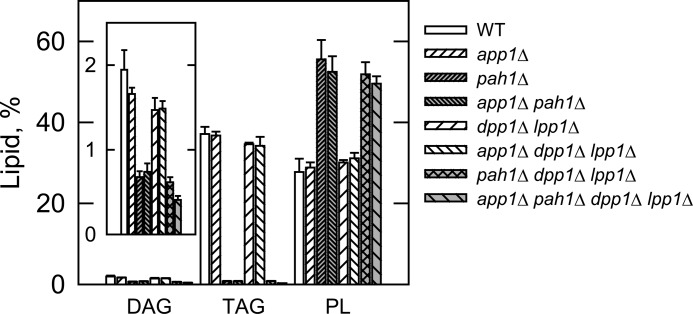

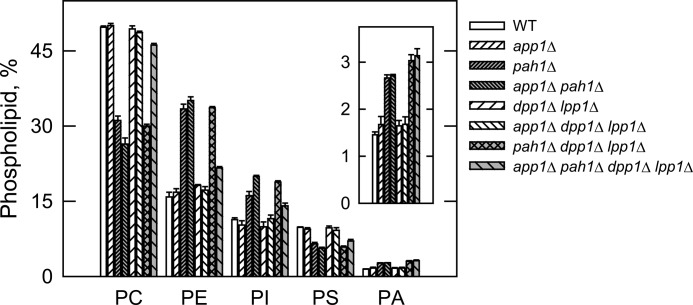

The PAP deletion mutants were used to determine the contribution of APP1, PAH1, DPP1, and LPP1 to lipid composition. In the first set of experiments, wild type and mutant cells were labeled to steady state with [2-14C]acetate to analyze DAG, TAG, and total phospholipids. Cells were grown to the stationary phase (the growth phase when DAG and TAG are most affected (27)), and lipids were extracted and then analyzed by one-dimensional TLC. When compared with the pah1Δ mutation, the app1Δ and dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutations did not have a significant effect on the relative amounts of DAG, TAG, and total phospholipids (Fig. 5). Moreover, alterations in lipid composition observed in the double, triple, and quadruple mutants were attributed to the pah1Δ mutation (Fig. 5). These results indicate that of the genes encoding PAP in S. cerevisiae, PAH1 is responsible for the synthesis of TAG and the regulation of phospholipid synthesis. In the second set of experiments, the wild type and mutant cells were labeled to steady state with [32P]Pi to analyze the composition of individual phospholipids. The phospholipids were extracted from exponential phase cells (the growth phase when phospholipid composition is most affected (27)) and analyzed by two-dimensional TLC. The relative amounts of the major phospholipids phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, and the precursor PA were not affected by the app1Δ and dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutations (Fig. 6). The relative amounts of these phospholipids, however, were affected by the pah1Δ mutation alone and in combination with the app1Δ and dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutations (Fig. 6). As described previously (27), the pah1Δ mutation caused decreases in the amounts of phosphatidylcholine (37%) and phosphatidylserine (33%) and increases in the amounts of phosphatidylethanolamine (108%), phosphatidylinositol (42%), and PA (86%). Interestingly, when combined with the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ mutations, the app1Δ mutation reversed the effect of the pah1Δ mutation on the composition of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine. The reason for this change is unclear.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of the PAP gene mutations on DAG, TAG, and total phospholipids. The indicated cells were grown to the stationary phase of growth in the presence of [2-14C]acetate (1 μCi/ml). Lipids were extracted and separated by one-dimensional TLC, and the images were subjected to ImageQuant analysis. The percentages shown for the individual lipids were normalized to the total 14C-labeled chloroform-soluble fraction, which also contained sterols, fatty acids, and unidentified neutral lipids. Each data point represents the average of three experiments ± S.D. (error bars). PL, phospholipids.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of the PAP gene mutations on phospholipid composition. The indicated cells were grown to the exponential phase of growth in the presence of [32P]Pi (10 μCi/ml). Phospholipids were extracted and separated by two-dimensional TLC, and the images were subjected to ImageQuant analysis. The percentages shown for the individual phospholipids were normalized to the total 32P-labeled chloroform-soluble fraction that included sphingolipids and unidentified phospholipids. Each data point represents the average of three experiments ± S.D. (error bars). Abbreviations: PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine.

The app1Δ Mutant Does Not Exhibit Obvious Phenotypes

We noted that the app1Δ mutant in the BY4741 genetic background exhibited slower growth on synthetic medium and was sensitive to elevated temperature (i.e. 37 °C). It is known that the BY4741 strain has more stringent growth requirements when compared with other strains used by the yeast research community (83). Accordingly, the growth requirements of the app1Δ mutant were also examined in the W303-1A genetic background. This analysis showed that the app1Δ mutation did not cause obvious growth defects. In addition, no striking phenotypes (e.g. changes in cellular morphology, respiratory deficiency, salt sensitivity) were identified. In striking contrast, the pah1Δ mutant exhibits a slow growth phenotype, is temperature-sensitive in several genetic backgrounds, and exhibits defects in cellular morphology (27, 43, 48, 49, 84). None of these phenotypes were complemented by the expression of APP1, substantiating that App1p and Pah1p PAP activities have distinct functions in lipid metabolism and cell physiology.

DISCUSSION

PAP is generally recognized as an important enzyme in eukaryotic organisms because its substrate PA and product DAG play important roles in the synthesis of TAG and phospholipids and in other aspects of cell physiology (e.g. transcription, lipid signaling, and vesicular trafficking) (1–20). Two basic types of PAP activity are found in eukaryotic organisms: an activity that is dependent on Mg2+ and an activity that is not dependent on Mg2+ or any other divalent cation (21, 22, 74). Mg2+-dependent PAP activity is governed by a DXDX(T/V) catalytic motif (77), whereas Mg2+-independent activity is directed by a three-domain catalytic motif consisting of the sequences KX6RP, PSGH, and SRX5HX3D (31). In the yeast S. cerevisiae, the Mg2+-dependent PAP is encoded by PAH1 (27), whereas the Mg2+-independent type of the enzyme is encoded by DPP1 (28) and LPP1 (29). The pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant lacking the known Mg2+-dependent and Mg2+-independent PAP enzymes still possesses the Mg2+-dependent activity that is sensitive to inhibition by N-ethylmaleimide (27), and the identity of the gene(s) encoding this activity was the focus of this work.

APP1 was identified through a reverse genetics approach using protein sequence information derived from the PAP enzyme isolated from the pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ triple mutant. Obtaining App1p sequence information was not straightforward. The PAP activity was labile in the absence of high salt, which comprised the effectiveness of chromatography steps that required low salt for enzyme binding (e.g. ion exchange chromatography). Although the eight-step purification scheme resulted in a 2,143-fold enrichment in PAP specific activity, it did not result in a homogeneous enzyme preparation that could facilitate unequivocal protein sequence determination. Although the sensitive liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry technology yielded many protein candidates, it allowed us to identify App1p that was present in very low abundance. In the end, the collective data (e.g. reduction of PAP activity in the app1Δ mutant, the APP1-directed overexpression of PAP activity in the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ quadruple mutant, and the heterologous expression of App1p PAP activity in E. coli) provided a conclusive level of evidence that APP1 is the structural gene encoding a PAP enzyme in S. cerevisiae.

Efforts to identify APP1 by informatics and by genetic approaches were unsuccessful. For example, a protein BLAST search using Pah1p as the query did not identify App1p or any other homologs in the Saccharomyces genome database. A BLAST search against higher eukaryotic organism databases identified mammalian lipin proteins, but this was expected because a BLAST search with mouse lipin-1 as the query identifies S. cerevisiae Pah1p (78). Likewise, a BLAST search using App1p as the query does not identify Pah1p or the mammalian lipins. Instead, the BLAST search identifies App1p homologs only found in fungi. A synthetic genetic array screen using the pah1Δ mutant in combination with the cho2Δ and opi3Δ mutations defective in the phosphatidylethanolamine methylation steps of phosphatidylcholine synthesis via the CDP-DAG pathway (85, 86) has also been performed.3 The rationale for this analysis was that the loss of a gene encoding PAP in combination with the loss of Pah1p causes lethality due to a lack of DAG production required for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine via the Kennedy pathway (85, 86). The genetic screen, however, did not lead to the identification of APP1,3 indicating that the cellular functions of App1p and Pah1p do not overlap with each other with respect to lipid synthesis. This assertion was further supported by the fact that APP1 did not complement phenotypes (e.g. temperature sensitivity) exhibited by the pah1Δ mutant and that the analysis of cells possessing the app1Δ mutation alone and in combination with mutations for other known PAP genes indicated that only Pah1p PAP was involved in de novo lipid synthesis.

Although there is essentially no sequence homology between App1p and Pah1p, both enzymes possess the canonical DXDX(T/V) catalytic motif that is typical of Mg2+-dependent phosphatase enzymes (77). For Pah1p, its DIDGT catalytic sequence is contained within the haloacid dehalogenase-like domain similar to that found in the mammalian lipin PAP enzymes (21, 23, 78). However, the haloacid dehalogenase-like domain is not found in App1p, but instead, it contains a conserved domain found only in fungi that has overlapping regions that show weak sequence similarity to the haloacid dehalogenase-like domain found in Pah1p and lipin (76). It is within this domain that the App1p DIDDT sequence is found (Fig. 2), and indeed, the D281E mutation abolished PAP activity, confirming this to be the catalytic sequence.

PAP enzymes isolated from S. cerevisiae are known to have molecular masses of 91 kDa (Mg2+-dependent) (87), 75 kDa (Mg2+-dependent) (88), 45 kDa (Mg2+-dependent) (89), and 34 kDa (Mg2+-independent) (34). Protein sequence information has confirmed that the 91-kDa enzyme is a proteolysis product of Pah1p (27) and that the 34-kDa enzyme is Dpp1p (28). Lpp1p PAP was identified based on its sequence homology with Dpp1p (29). The identity of the genes encoding the 75- and 45-kDa forms of PAP has been an enigma. Although the basic enzymological properties of these enzymes are similar, the 75-kDa enzyme is soluble, whereas the 45-kDa enzyme is associated with mitochondria (88, 89). Because of the differences in size and location, it has been assumed that the 75- and 45-kDa PAP enzymes are encoded by different genes. Based on the result that no detectable PAP activity was present in the app1Δ pah1Δ dpp1Δ lpp1Δ quadruple mutant, we hypothesize that the 75-kDa PAP was the soluble form of App1p and that the 45-kDa PAP was a proteolytic fragment of App1p bound to mitochondrial membranes. Unfortunately, this hypothesis cannot be addressed because preparations of the 75- and 45-kDa PAP enzymes are no longer available. Obviously, the protein used for sequence analysis in this study was a proteolytic fragment of App1p.

The PAP enzymes in S. cerevisiae are found in different cellular locations and play diverse roles in cell physiology (74). Pah1p is a cytosolic enzyme that associates with and functions at the nuclear/endoplasmic reticulum membrane to regulate the synthesis of TAG and membrane phospholipids (21, 22, 27, 42, 74). Dpp1p and Lpp1p, respectively, are thought to control the signaling functions of PA, DAG pyrophosphate, and lysoPA in vacuole and Golgi membranes (21, 22, 28, 29, 34, 44–46, 74, 90). Like Pah1p, App1p is a cytosolic protein (46) that associates with membranes, but the role this PAP plays in cell physiology is not yet clear.

The formation of endocytic vesicles in S. cerevisiae involves a series of processes that include actin patch assembly, actin polymerization, and changes in membrane structure and curvature (75, 92). These processes involve numerous endocytic proteins, and App1p is known to physically interact with many of them (67–75) (Fig. 2). Although these interactions have yet to be studied in detail, the presence of proline-rich regions (PXXP motifs) in App1p suggests interactions with SH3 domains of Abp1p, Ysc84p, Sla1p, Bbc1p, Bzz1p, and Rvs167p (79, 80). App1p interactions with proteins that do not possess SH3 domains (e.g. Las17p, Sla2p, Cof1p, Crn1p, and Rvs161) must occur through other mechanisms yet to be defined. Based on these protein interaction data, App1p is postulated to play a role in endocytosis (67). However, until now the molecular function of App1p has been unknown. App1p PAP located at cortical actin patches (92) may regulate the local concentrations of PA and DAG. These lipids are known to facilitate membrane fission/fusion events in model systems (93–98), and they are also known to interact with and regulate enzymes (e.g. phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate kinase, protein kinase C, protein kinase D) that play important roles in vesicular trafficking (99–103). For example, in mammalian cells, the inhibition of PAP activity by propranolol attenuates protein kinase D recruitment to Golgi membranes, blocking vesicle bud formation and protein transport to the cell surface (103, 104). Unfortunately, propranolol does not discriminate between Mg2+-dependent and Mg2+-independent PAP activities (90, 105–107), and thus, the identity of the type of PAP enzyme involved in this process is unknown. We speculate that in yeast, App1p PAP activity plays a role in vesicle formation through its recruitment from the cytosol to cortical actin patches via endocytic proteins. These proteins may tether App1p PAP to actin patches and/or serve to regulate the relative amounts of PA and DAG, which in turn contribute to the control of vesicle formation. Clearly, the work reported here provides an impetus to pursue these questions in more detail. Although an App1p homolog does not exist in higher eukaryotes, a functional homolog exists in the form of the lipin PAP enzymes that catalyze the same reaction (27, 106, 108), and as indicated above, a PAP activity is implicated in vesicular trafficking in mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

Chris A. Marfo is acknowledged for the initial characterization of the anti-App1p antibodies. The mass spectrometry data were obtained from an Orbitrap instrument funded in part by National Institutes of Health Grant NS046593, for the support of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Neuroproteomics Core Facility.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-28140 (to G. M. C.) from the United States Public Health Service.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

C. R. McMaster, personal communication.

- PAP

- phosphatidate phosphatase

- PA

- phosphatidate

- lysoPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- TAG

- triacylglycerol

- SH3

- Src homology 3

- Ni2+-NTA

- Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smith S. W., Weiss S. B., Kennedy E. P. (1957) The enzymatic dephosphorylation of phosphatidic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 228, 915–922 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kennedy E. P., Weiss S. B. (1956) The function of cytidine coenzyme in the biosynthesis of phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 222, 193–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borkenhagen L. F., Kennedy E. P. (1957) The enzymatic synthesis of cytidine diphosphate choline. J. Biol. Chem. 227, 951–962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weiss S. B., Smith S. W., Kennedy E. P. (1958) The enzymatic formation of lecithin from cytidine diphosphate choline and d-1,2-diglyceride. J. Biol. Chem. 231, 53–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kennedy E. P. (1956) The synthesis of cytidine diphosphate choline, cytidine diphosphate ethanolamine, and related compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 222, 185–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weiss S. B., Kennedy E. P., Kiyasu J. Y. (1960) The enzymatic synthesis of triglycerides. J. Biol. Chem. 235, 40–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paulus H., Kennedy E. P. (1960) The enzymatic synthesis of inositol monophosphatide. J. Biol. Chem. 235, 1303–1311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kiyasu J. Y., Pieringer R. A., Paulus H., Kennedy E. P. (1963) The biosynthesis of phosphatidylglycerol. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 2293–2298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davidson J. B., Stanacev N. Z. (1971) Biosynthesis of cardiolipin in mitochondria isolated from guinea pig liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 42, 1191–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bishop W. R., Ganong B. R., Bell R. M. (1986) Attenuation of sn-1,2-diacylglycerol second messengers by diacylglycerol kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 6993–7000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kearns B. G., McGee T. P., Mayinger P., Gedvilaite A., Phillips S. E., Kagiwada S., Bankaitis V. A. (1997) Essential role for diacylglycerol in protein transport from the yeast Golgi complex. Nature 387, 101–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waggoner D. W., Xu J., Singh I., Jasinska R., Zhang Q. X., Brindley D. N. (1999) Structural organization of mammalian lipid phosphate phosphatases: implications for signal transduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1439, 299–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sciorra V. A., Morris A. J. (2002) Roles for lipid phosphate phosphatases in regulation of cellular signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1582, 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Testerink C., Munnik T. (2005) Phosphatidic acid: a multifunctional stress signaling lipid in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang X., Devaiah S. P., Zhang W., Welti R. (2006) Signaling functions of phosphatidic acid. Prog. Lipid Res. 45, 250–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brindley D. N. (2004) Lipid phosphate phosphatases and related proteins: signaling functions in development, cell division, and cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 92, 900–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Howe A. G., McMaster C. R. (2006) Regulation of phosphatidylcholine homeostasis by Sec14. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84, 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foster D. A. (2007) Regulation of mTOR by phosphatidic acid? Cancer Res. 67, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carman G. M., Henry S. A. (2007) Phosphatidic acid plays a central role in the transcriptional regulation of glycerophospholipid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37293–37297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carrasco S., Mérida I. (2007) Diacylglycerol, when simplicity becomes complex. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carman G. M., Han G.-S. (2006) Roles of phosphatidate phosphatase enzymes in lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 694–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carman G. M., Han G.-S. (2009) Phosphatidic acid phosphatase, a key enzyme in the regulation of lipid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2593–2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Csaki L. S., Reue K. (2010) Lipins: multifunctional lipid metabolism proteins. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 30, 257–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reue K., Dwyer J. R. (2009) Lipin proteins and metabolic homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 50, (suppl.) S109–S114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reue K., Brindley D. N. (2008) Multiple roles for lipins/phosphatidate phosphatase enzymes in lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 49, 2493–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pascual F., Carman G. M. (2012) Phosphatidate phosphatase, a key regulator of lipid homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han G.-S., Wu W.-I., Carman G. M. (2006) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9210–9218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Toke D. A., Bennett W. L., Dillon D. A., Wu W.-I., Chen X., Ostrander D. B., Oshiro J., Cremesti A., Voelker D. R., Fischl A. S., Carman G. M. (1998) Isolation and characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DPP1 gene encoding for diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3278–3284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Toke D. A., Bennett W. L., Oshiro J., Wu W.-I., Voelker D. R., Carman G. M. (1998) Isolation and characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae LPP1 gene encoding a Mg2+-independent phosphatidate phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14331–14338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han G.-S., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2007) The cellular functions of the yeast lipin homolog Pah1p are dependent on its phosphatidate phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37026–37035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stukey J., Carman G. M. (1997) Identification of a novel phosphatase sequence motif. Protein Sci. 6, 469–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toke D. A., McClintick M. L., Carman G. M. (1999) Mutagenesis of the phosphatase sequence motif in diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 38, 14606–14613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dillon D. A., Chen X., Zeimetz G. M., Wu W.-I., Waggoner D. W., Dewald J., Brindley D. N., Carman G. M. (1997) Mammalian Mg2+-independent phosphatidate phosphatase (PAP2) displays diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10361–10366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu W.-I., Liu Y., Riedel B., Wissing J. B., Fischl A. S., Carman G. M. (1996) Purification and characterization of diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1868–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dillon D. A., Wu W.-I., Riedel B., Wissing J. B., Dowhan W., Carman G. M. (1996) The Escherichia coli pgpB gene encodes for a diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30548–30553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Faulkner A., Chen X., Rush J., Horazdovsky B., Waechter C. J., Carman G. M., Sternweis P. C. (1999) The LPP1 and DPP1 gene products account for most of the isoprenoid phosphatase activities in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14831–14837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choi H.-S., Su W.-M., Han G.-S., Plote D., Xu Z., Carman G. M. (2012) Pho85p-Pho80p phosphorylation of yeast Pah1p phosphatidate phosphatase regulates its activity, location, abundance, and function in lipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11290–11301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Choi H.-S., Su W.-M., Morgan J. M., Han G.-S., Xu Z., Karanasios E., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2011) Phosphorylation of phosphatidate phosphatase regulates its membrane association and physiological functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of Ser602, Thr723, and Ser744 as the sites phosphorylated by CDC28 (CDK1)-encoded cyclin-dependent kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1486–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Su W.-M., Han G.-S., Casciano J., Carman G. M. (2012) Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of Pah1p phosphatidate phosphatase functions in conjunction with the Pho85p-Pho80p and Cdc28p-cyclin B kinases to regulate lipid synthesis in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33364–33376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blom N., Sicheritz-Pontén T., Gupta R., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. (2004) Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 4, 1633–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Siniossoglou S., Santos-Rosa H., Rappsilber J., Mann M., Hurt E. (1998) A novel complex of membrane proteins required for formation of a spherical nucleus. EMBO J. 17, 6449–6464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karanasios E., Han G.-S., Xu Z., Carman G. M., Siniossoglou S. (2010) A phosphorylation-regulated amphipathic helix controls the membrane translocation and function of the yeast phosphatidate phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17539–17544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Santos-Rosa H., Leung J., Grimsey N., Peak-Chew S., Siniossoglou S. (2005) The yeast lipin Smp2 couples phospholipid biosynthesis to nuclear membrane growth. EMBO J. 24, 1931–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han G.-S., Johnston C. N., Chen X., Athenstaedt K., Daum G., Carman G. M. (2001) Regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DPP1-encoded diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase by zinc. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10126–10133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Han G.-S., Johnston C. N., Carman G. M. (2004) Vacuole membrane topography of the DPP1-encoded diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase catalytic site from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5338–5345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., Weissman J. S., O'Shea E. K. (2003) Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425, 686–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fakas S., Qiu Y., Dixon J. L., Han G.-S., Ruggles K. V., Garbarino J., Sturley S. L., Carman G. M. (2011) Phosphatidate phosphatase activity plays a key role in protection against fatty acid-induced toxicity in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29074–29085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Adeyo O., Horn P. J., Lee S., Binns D. D., Chandrahas A., Chapman K. D., Goodman J. M. (2011) The yeast lipin orthologue Pah1p is important for biogenesis of lipid droplets. J. Cell Biol. 192, 1043–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sasser T., Qiu Q. S., Karunakaran S., Padolina M., Reyes A., Flood B., Smith S., Gonzales C., Fratti R. A. (2012) The yeast lipin 1 orthologue Pah1p regulates vacuole homeostasis and membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2221–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rose M. D., Winston F., Heiter P. (1990) Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. (1983) Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153, 163–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H. (1990) in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications (Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J., eds) pp. 3–12, Academic Press, Inc., San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rothstein R. (1991) Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: Integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194, 281–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fischl A. S., Carman G. M. (1983) Phosphatidylinositol biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: purification and properties of microsome-associated phosphatidylinositol synthase. J. Bacteriol. 154, 304–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Belendiuk G., Mangnall D., Tung B., Westley J., Getz G. S. (1978) CTP-phosphatidic acid cytidyltransferase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: partial purification, characterization, and kinetic behavior. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 4555–4565 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Carman G. M., Lin Y.-P. (1991) Phosphatidate phosphatase from yeast. Methods Enzymol. 197, 548–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Burnette W. (1981) Western blotting: Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal. Biochem. 112, 195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Haid A., Suissa M. (1983) Immunochemical identification of membrane proteins after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 96, 192–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Das A., Li H., Liu T., Bellofatto V. (2006) Biochemical characterization of Trypanosoma brucei RNA polymerase II. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 150, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jain M. R., Li Q., Liu T., Rinaggio J., Ketkar A., Tournier V., Madura K., Elkabes S., Li H. (2012) Proteomic identification of immunoproteasome accumulation in formalin-fixed rodent spinal cords with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Proteome Res. 11, 1791–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Esko J. D., Raetz C. R. (1980) Mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells with altered membrane phospholipid composition: replacement of phosphatidylinositol by phosphatidylglycerol in a myo-inositol auxotroph. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 4474–4480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Henderson R. J., Tocher D. R. (1992) in Lipid Analysis (Hamilton R. J., Hamilton S., eds) pp. 65–111, IRL Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 67. Drees B. L., Sundin B., Brazeau E., Caviston J. P., Chen G. C., Guo W., Kozminski K. G., Lau M. W., Moskow J. J., Tong A., Schenkman L. R., McKenzie A., 3rd, Brennwald P., Longtine M., Bi E., Chan C., Novick P., Boone C., Pringle J. R., Davis T. N., Fields S., Drubin D. G. (2001) A protein interaction map for cell polarity development. J. Cell Biol. 154, 549–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bon E., Recordon-Navarro P., Durrens P., Iwase M., Toh-E A., Aigle M. (2000) A network of proteins around Rvs167p and Rvs161p, two proteins related to the yeast actin cytoskeleton. Yeast 16, 1229–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ho Y., Gruhler A., Heilbut A., Bader G. D., Moore L., Adams S. L., Millar A., Taylor P., Bennett K., Boutilier K., Yang L., Wolting C., Donaldson I., Schandorff S., Shewnarane J., Vo M., Taggart J., Goudreault M., Muskat B., Alfarano C., Dewar D., Lin Z., Michalickova K., Willems A. R., Sassi H., Nielsen P. A., Rasmussen K. J., Andersen J. R., Johansen L. E., Hansen L. H., Jespersen H., Podtelejnikov A., Nielsen E., Crawford J., Poulsen V., Sørensen B. D., Matthiesen J., Hendrickson R. C., Gleeson F., Pawson T., Moran M. F., Durocher D., Mann M., Hogue C. W., Figeys D., Tyers M. (2002) Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415, 180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tong A. H., Drees B., Nardelli G., Bader G. D., Brannetti B., Castagnoli L., Evangelista M., Ferracuti S., Nelson B., Paoluzi S., Quondam M., Zucconi A., Hogue C. W., Fields S., Boone C., Cesareni G. (2002) A combined experimental and computational strategy to define protein interaction networks for peptide recognition modules. Science 295, 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fazi B., Cope M. J., Douangamath A., Ferracuti S., Schirwitz K., Zucconi A., Drubin D. G., Wilmanns M., Cesareni G., Castagnoli L. (2002) Unusual binding properties of the SH3 domain of the yeast actin-binding protein Abp1: structural and functional analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5290–5298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Landgraf C., Panni S., Montecchi-Palazzi L., Castagnoli L., Schneider-Mergener J., Volkmer-Engert R., Cesareni G. (2004) Protein interaction networks by proteome peptide scanning. PLoS. Biol. 2, E14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tonikian R., Xin X., Toret C. P., Gfeller D., Landgraf C., Panni S., Paoluzi S., Castagnoli L., Currell B., Seshagiri S., Yu H., Winsor B., Vidal M., Gerstein M. B., Bader G. D., Volkmer R., Cesareni G., Drubin D. G., Kim P. M., Sidhu S. S., Boone C. (2009) Bayesian modeling of the yeast SH3 domain interactome predicts spatiotemporal dynamics of endocytosis proteins. PLoS. Biol. 7, e1000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yu H., Braun P., Yildirim M. A., Lemmens I., Venkatesan K., Sahalie J., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Gebreab F., Li N., Simonis N., Hao T., Rual J. F., Dricot A., Vazquez A., Murray R. R., Simon C., Tardivo L., Tam S., Svrzikapa N., Fan C., de Smet A. S., Motyl A., Hudson M. E., Park J., Xin X., Cusick M. E., Moore T., Boone C., Snyder M., Roth F. P., Barabási A. L., Tavernier J., Hill D. E., Vidal M. (2008) High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science 322, 104–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Michelot A., Costanzo M., Sarkeshik A., Boone C., Yates J. R., 3rd, Drubin D. G. (2010) Reconstitution and protein composition analysis of endocytic actin patches. Curr. Biol. 20, 1890–1899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., Pang N., Forslund K., Ceric G., Clements J., Heger A., Holm L., Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Bateman A., Finn R. D. (2012) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290-D301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Madera M., Vogel C., Kummerfeld S. K., Chothia C., Gough J. (2004) The SUPERFAMILY database in 2004: additions and improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D235-D239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Péterfy M., Phan J., Xu P., Reue K. (2001) Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat. Genet. 27, 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Feng S., Chen J. K., Yu H., Simon J. A., Schreiber S. L. (1994) Two binding orientations for peptides to the Src SH3 domain: development of a general model for SH3-ligand interactions. Science 266, 1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lim W. A., Richards F. M., Fox R. O. (1994) Structural determinants of peptide-binding orientation and of sequence specificity in SH3 domains. Nature 372, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hosaka K., Yamashita S. (1984) Regulatory role of phosphatidate phosphatase in triacylglycerol synthesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 796, 110–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Oshiro J., Rangaswamy S., Chen X., Han G.-S., Quinn J. E., Carman G. M. (2000) Regulation of the DPP1-encoded diacylglycerol pyrophosphate (DGPP) phosphatase by inositol and growth phase: inhibition of DGPP phosphatase activity by CDP-diacylglycerol and activation of phosphatidylserine synthase activity by DGPP. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40887–40896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hanscho M., Ruckerbauer D. E., Chauhan N., Hofbauer H. F., Krahulec S., Nidetzky B., Kohlwein S. D., Zanghellini J., Natter K. (2012) Nutritional requirements of the BY series of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for optimum growth. FEMS Yeast Res. 12, 796–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Irie K., Takase M., Araki H., Oshima Y. (1993) A gene, SMP2, involved in plasmid maintenance and respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a highly charged protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 236, 283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Carman G. M., Han G.-S. (2011) Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 80, 859–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Henry S. A., Kohlwein S. D., Carman G. M. (2012) Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 190, 317–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lin Y.-P., Carman G. M. (1989) Purification and characterization of phosphatidate phosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8641–8645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hosaka K., Yamashita S. (1984) Partial purification and properties of phosphatidate phosphatase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 796, 102–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Morlock K. R., McLaughlin J. J., Lin Y.-P., Carman G. M. (1991) Phosphatidate phosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of 45-kDa and 104-kDa forms of the enzyme that are differentially regulated by inositol. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 3586–3593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Furneisen J. M., Carman G. M. (2000) Enzymological properties of the LPP1-encoded lipid phosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1484, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hill J. E., Myers A. M., Koerner T. J., Tzagoloff A. (1986) Yeast/E. coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast 2, 163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Weinberg J., Drubin D. G. (2012) Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 1–1322018597 [Google Scholar]

- 93. Liao M. J., Prestegard J. H. (1979) Fusion of phosphatidic acid-phosphatidylcholine mixed lipid vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 550, 157–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Koter M., de Kruijff B., van Deenen L. L. (1978) Calcium-induced aggregation and fusion of mixed phosphatidylcholine-phosphatidic acid vesicles as studied by 31P NMR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 514, 255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Blackwood R. A., Smolen J. E., Transue A., Hessler R. J., Harsh D. M., Brower R. C., French S. (1997) Phospholipase D activity facilitates Ca2+-induced aggregation and fusion of complex liposomes. Am. J. Physiol. 272, C1279-C1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Weigert R., Silletta M. G., Spanò S., Turacchio G., Cericola C., Colanzi A., Senatore S., Mancini R., Polishchuk E. V., Salmona M., Facchiano F., Burger K. N., Mironov A., Luini A., Corda D. (1999) CtBP/BARS induces fission of Golgi membranes by acylating lysophosphatidic acid. Nature 402, 429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Goñi F. M., Alonso A. (1999) Structure and functional properties of diacylglycerols in membranes. Prog. Lipid Res. 38, 1–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Chernomordik L., Kozlov M. M., Zimmerberg J. (1995) Lipids in biological membrane fusion. J. Membr. Biol. 146, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Roth M. G. (2008) Molecular mechanisms of PLD function in membrane traffic. Traffic. 9, 1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Morris A. J. (2007) Regulation of phospholipase D activity, membrane targeting, and intracellular trafficking by phosphoinositides. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Maissel A., Marom M., Shtutman M., Shahaf G., Livneh E. (2006) PKCη is localized in the Golgi, ER, and nuclear envelope and translocates to the nuclear envelope upon PMA activation and serum-starvation: C1b domain and the pseudosubstrate containing fragment target PKCη to the Golgi and the nuclear envelope. Cell. Signal. 18, 1127–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lehel C., Oláh Z., Jakab G., Szállási Z., Petrovics G., Harta G., Blumberg P. M., Anderson W. B. (1995) Protein kinase C ϵ subcellular localization domains and proteolytic degradation sites: a model for protein kinase C conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19651–19658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Baron C. L., Malhotra V. (2002) Role of diacylglycerol in PKD recruitment to the TGN and protein transport to the plasma membrane. Science 295, 325–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Asp L., Kartberg F., Fernandez-Rodriguez J., Smedh M., Elsner M., Laporte F., Bárcena M., Jansen K. A., Valentijn J. A., Koster A. J., Bergeron J. J., Nilsson T. (2009) Early stages of Golgi vesicle and tubule formation require diacylglycerol. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 780–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Jamal Z., Martin A., Gomez-Muñoz A., Brindley D. N. (1991) Plasma membrane fractions from rat liver contain a phosphatidate phosphohydrolase distinct from that in the endoplasmic reticulum and cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 2988–2996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Han G.-S., Carman G. M. (2010) Characterization of the human LPIN1-encoded phosphatidate phosphatase isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14628–14638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Havriluk T., Lozy F., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2008) Colorimetric determination of pure Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase activity. Anal. Biochem. 373, 392–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Donkor J., Sariahmetoglu M., Dewald J., Brindley D. N., Reue K. (2007) Three mammalian lipins act as phosphatidate phosphatases with distinct tissue expression patterns. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3450–3457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Brachmann C. B., Davies A., Cost G. J., Caputo E., Li J., Hieter P., Boeke J. D. (1998) Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Thomas B. J., Rothstein R. (1989) Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell 56, 619–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]