Background: Mutant myocilin accumulates in the endoplasmic reticulum for unknown reasons.

Results: Glucose-regulated protein (Grp) 94 depletion reduces mutant myocilin by engaging autophagy.

Conclusion: Grp94 triages mutant myocilin through ER-associated degradation, subverting autophagy.

Significance: Treating glaucoma could be possible by inhibiting Grp94 and reducing its novel client, mutant myocilin.

Keywords: Amyloid, Autophagy, Chaperone Chaperonin, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Proteasome, Protein Misfolding, Protein Stability, Protein Turnover

Abstract

Clearance of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is traditionally handled by ER-associated degradation (ERAD), a process that requires retro-translocation and ubiquitination mediated by a luminal chaperone network. Here we investigated whether the secreted, glaucoma-associated protein myocilin was processed by this pathway. Myocilin is typically transported through the ER/Golgi network, but inherited mutations in myocilin lead to its misfolding and aggregation within trabecular meshwork cells, and ultimately, ER stress-induced cell death. Using targeted knockdown strategies, we determined that glucose-regulated protein 94 (Grp94), the ER equivalent of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), specifically recognizes mutant myocilin, triaging it through ERAD. The addition of mutant myocilin to the short list of Grp94 clients strengthens the hypothesis that β-strand secondary structure drives client association with Grp94. Interestingly, the ERAD pathway is incapable of efficiently handling the removal of mutant myocilin, but when Grp94 is depleted, degradation of mutant myocilin is shunted away from ERAD toward a more robust clearance pathway for aggregation-prone proteins, the autophagy system. Thus ERAD inefficiency for distinct aggregation-prone proteins can be subverted by manipulating ER chaperones, leading to more effective clearance by the autophagic/lysosomal pathway. General Hsp90 inhibitors and a selective Grp94 inhibitor also facilitate clearance of mutant myocilin, suggesting that therapeutic approaches aimed at inhibiting Grp94 could be beneficial for patients suffering from some cases of myocilin glaucoma.

Introduction

Myocilin is the gene product most closely linked to early onset, inherited primary open angle glaucoma, accounting for more than 10% of juvenile and 5% of adult-onset disease (1, 2). Though it is expressed throughout the body, myocilin only appears to cause disease as part of its role in the trabecular meshwork, a tissue in the anterior segment of the eye that controls aqueous humor outflow and helps regulate intraocular pressure (3). Dysregulation of fluid flow leads to elevated intraocular pressure, a major risk factor for glaucoma (4). Amino acid-altering mutations in the gene encoding myocilin lead to sequestration and accumulation of mutant myocilin (5–9), particularly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 (5, 6) of trabecular meshwork cells. The toxic consequences of cell stress (10) and death (5–7) that lead to a compromised trabecular meshwork and a hastening of glaucoma phenotypes. More than 70 mutations in myocilin clustered in its C-terminal ∼30-kDa olfactomedin domain have been documented (11), with differing severity in terms of age of onset (11), cellular toxicity (8, 9), and extent of thermal destabilization of the olfactomedin domain (12, 13). Importantly, pathogenesis is a gain-of-toxic-function, as myocilin knock-out mice (14) and individuals harboring premature stop codons that prevent myocilin translation (15) do not develop glaucoma. The nature of the aggregate and its toxicity has not been unambiguously identified, but the unfolded protein response is up-regulated in cells expressing high levels of wild-type myocilin (16), and ER stress response genes are up-regulated both in cells (5) and mice (17) expressing mutant myocilin. Mutant myocilin also readily forms a detergent-insoluble species (18) consisting of amyloid fibrils, a specific misfolded species that is recalcitrant to disaggregation, in vitro and in a cellular model (19).

Despite the interest in developing therapeutic routes to mitigate myocilin aggregation and toxicity, primarily by promoting its secretion (6, 7, 12, 17, 20, 21), it is not understood why myocilin, unlike other mutant proteins, is not efficiently cleared by ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Misfolded proteins are typically efficiently ubiquitinated in association with the ER membrane and retro-translocated to the cytosol for proteasomal degradation (22), a mechanism that appears to be challenged in the case of mutant myocilin. Chaperone proteins within the ER, primarily ATPases glucose-regulated protein 94 (Grp94) (a heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) family member) and Grp78 (a Hsp70 family member, also called BiP), are essential for triage decisions about protein fate. The exact order in which ER clients are processed by chaperones is unknown; however, Grp94 seems to be more selective for a distinct client sub-set (23). Indeed, Grp94 and Grp78 have been shown to co-localize with mutant myocilin (5–7, 17), but the significance of this co-localization has remained elusive. ERAD-related loss of function because of inherited mutation is associated with myriad diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (24) and Gaucher disease (25), among many others. A better understanding of mutant myocilin ER retention could lead to corrective measures that would reduce its accumulation through manipulation of the ER quality control system.

Here we evaluated the interactions of myocilin with the chaperone network and show that Grp94 is involved in mutant myocilin turnover. Disease-causing mutations in myocilin drive its interaction with Grp94, but this appears to facilitate an inefficient route of clearance for mutant myocilin involving ERAD that results in mutant myocilin accumulation. By depleting Grp94 either by RNA knockdown or with pharmacological agents, mutant myocilin was effectively removed through an alternative clearance pathway involving autophagy. Such a strategy could represent a therapeutic approach for myocilin glaucoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA Constructs and siRNA

All myocilin cDNA constructs were a generous gift from Dr. Vincent Raymond (Laval University Hospital (CHUL) Research Center). VCP constructs were provided by Dr. Tom Rapoport (Harvard Medical School). siRNAs were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Where possible, a validated siRNA was used. Otherwise, two siRNAs were purchased for each gene, and knockdown efficiency was tested as described previously (26). Sequences are available upon request.

Antibodies

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody was obtained from Meridian Life Science (Saco, ME). FLAG mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from Sigma. Myocilin antibody was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MI). Calnexin and Beclin-1 antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA). Lamp2 antibody was provided by the University of Iowa hybridoma bank. All secondary antibodies were HRP-linked and obtained from Southern Biotechnologies (Birmingham, AL) and added at a dilution of 1:1000. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen.

Compounds

The selective Grp94 inhibitor was a generous gift from Dr. Brian Blagg (University of Kansas). Epoxomicin was a gift from Elan Pharmaceuticals (San Francisco, CA). All compounds were solubilized in DMSO. Mixtures were diluted such that the final concentration of DMSO in cell media was less than 1%.

Drug Treatments

Cells were treated with Grp94 or Hsp90 inhibitor for 24 h. Proteasomal inhibition was achieved by treating cells with 0.6 μm and 0.8 μm epoxomicin.

Dot Blotting

An appropriate amount of supernatant from each sample was added into each well of the dot blot apparatus and suctioned onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then washed with PBS (filtered) twice and placed on Ponceau S. The membrane was blocked with 7% milk and probed with myocilin or FLAG antibodies.

Cell Culture and Transfections

Cells were plated and grown as described previously (27, 28). The tetracycline-responsive human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell models and normal HEK cells were used as described previously (27). Cells were grown and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10%, Tet system-approved, fetal bovine serum (Clontech Laboratories), penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), hygromycin B (200 μg/ml), and G418 (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Inducible cells were treated with 5 μg/μl tetracycline to induce myocilin expression, 24 h prior to transfection. siRNA transfections were performed with siLentFect reagent (Bio-Rad). DNA transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 48 h. The cells were harvested in Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (M-PER) buffer (Pierce) containing 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem), 100 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1× phosphatase inhibitor II and III mixtures (Sigma).

Western Blotting and Co-Immunoprecipitation

Western blot and co-immunoprecipitation analyses were performed as described previously (29). Protein samples were prepared using 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad). Samples were boiled for 5–10 min and then loaded onto a 10-well, 10% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) or 18-well, 10% criterion gels (Bio-Rad). The gels were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore) and then blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 7% milk. For co-immunoprecipitations, cells were harvested with co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl and 150 mm NaCl) containing 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem), 100 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1× phosphatase inhibitor II and III mixtures (Sigma). Lysates were then pre-cleared with a 20 μl slurry of Protein G beads for 1 h at 4 °C. Pre-cleared samples were incubated with myocilin antibody for 4 h at 4 °C. 50 μl of Protein G beads were added onto the samples and incubated overnight. Samples were washed with co-IP buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence and Co-localization Studies

Tetracycline-responsive HEK cells stably transfected with myocilin and induced as described above were grown in chamber slides (Labtek, Scotts Valley, CA). siRNA was performed as described above. The slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Co-staining was performed with αFLAG antibody (1:500 dilution) and DAPI (Fig. 1E), or αFLAG, α-calnexin (1:50 dilution) and α-ubiquitin (1:50 dilution; Fig. 4) antibodies. Appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were added at a 1:1500 dilution. DAPI was added to stain the nuclei at a 1:20000 dilution where indicated. Slides were imaged and co-localization was analyzed with the Zeiss AxioImager.Z1 with ApoTome and AxioVision software using 20×, 63×, and 100× objectives, or the Olympus FV1000 MPE Multiphoton Laser Scanning Microscope. Co-localization was assessed using the Pearson's coefficient as described previously (30), and image intensity was assessed where indicated using ImageJ following normalization to DAPI signal.

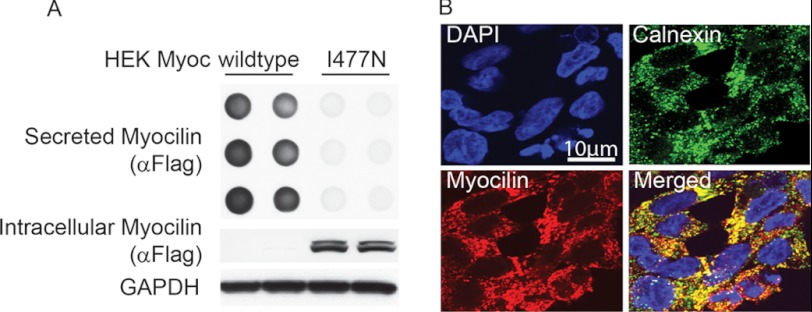

FIGURE 1.

Validation of inducible cell model. HEK cells stably over-expressing tetracycline-regulatable FLAG-tagged wild type (iWT) and I477N mutant (iI477N) myocilin were generated as described previously. A, dot blot analysis of cell culture media and Western blot of lysates were retrieved from both cell lines 96 h following tetracycline administration. B, immunofluorescent co-localization imaging for myocilin (anti-FLAG, red) and the ER marker calnexin (green) of HEK iI477N cells conditionally shows co-localization of myocilin with the ER.

FIGURE 4.

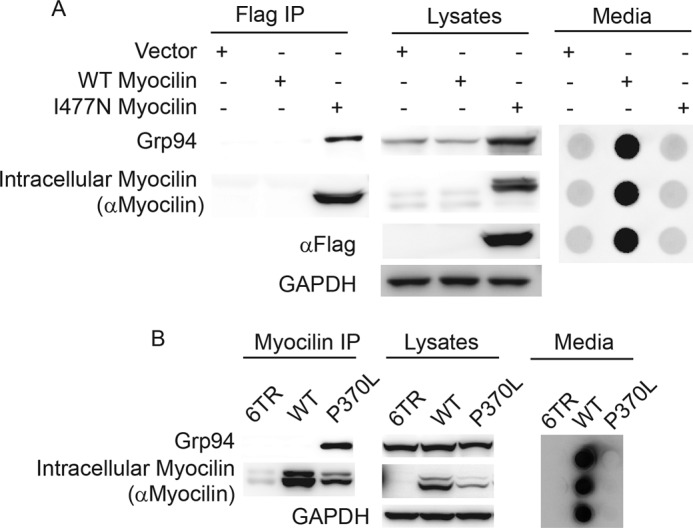

Association of Grp94 with mutant but not wild type myocilin. A, co-IP of FLAG-tagged myocilin from HEK iI477N or iWT cells followed by Western blot analysis to detect Grp94, myocilin, and GAPDH. Media from cells show secretion of wild type but not I477N myocilin as expected. B, co-IP of myocilin from HEK cell lysates transiently over-expressing wild type (WT) or P370L myocilin, followed by Western blot for myocilin, Grp94, and GAPDH. As expected, transient over-expression of wild type myocilin results in high levels of intracellular myocilin as well as secreted myocilin (see also supplemental Fig. S1). P370L was not secreted to the media.

Quantification and Statistical Analyses

Quantification of all blots was performed using ImageJ software as described previously (30). Graphs are plotted based on relative intensity values. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t tests or as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Validation of Myocilin-inducible Cell Model

A well established HEK cell model that conditionally overexpresses wild type (iWT) or I477N mutant myocilin (iI477N) was used in these studies (27). In this inducible and stable cell line, wild type or I477N myocilin harbors a FLAG tag to ease downstream detection. We confirmed wild type myocilin secretion and I477N intracellular retention using dot blot analysis of the cell culture media or Western blotting of the lysates, respectively (Fig. 1A). We further corroborated ER retention of I477N myocilin by immunofluorescence co-localization (Fig. 1B).

Effect of siRNA-mediated Knockdown of Chaperones on Myocilin

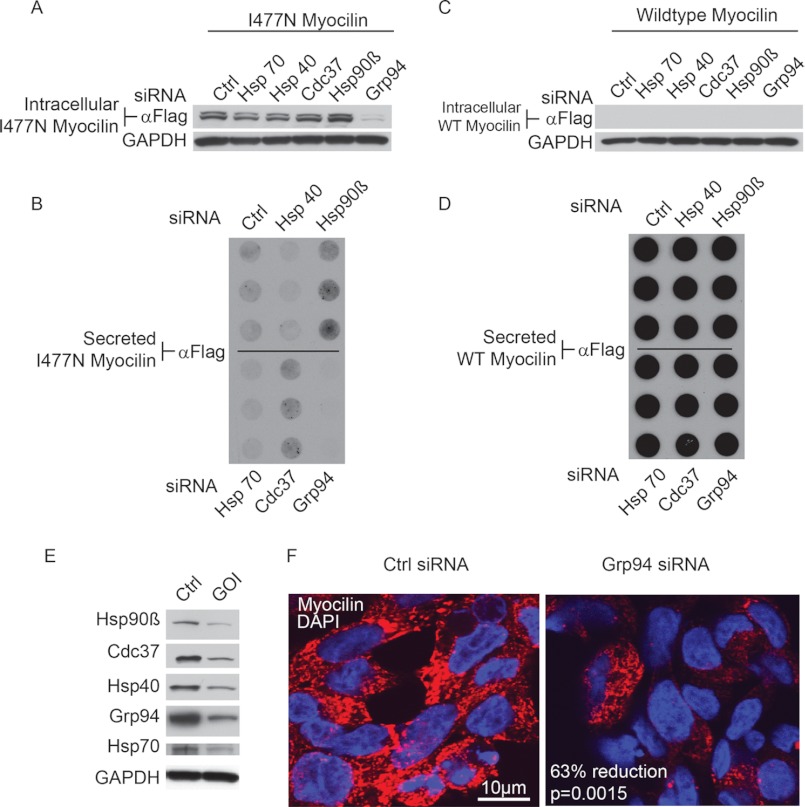

The effects of knocking down several chaperones were evaluated in both the iWT and iI477N cell models using siRNA. Of the chaperones tested, which included Hsp70, Hsp40, cell division control 37 (Cdc37), Hsp90β, and Grp94 (31), only silencing of Grp94 caused a marked reduction in intracellular I477N myocilin (Fig. 2A). Dot blot analysis of the media revealed a slight increase in secreted I477N myocilin upon Hsp90β and Cdc37 knockdown, whereas no secretion was observed with Grp94 knockdown (Fig. 2B). The levels of intracellular (Fig. 2C) and secreted (Fig. 2D) wild type myocilin were not affected by knockdown of any of these chaperones. Knockdown was confirmed for each experiment by Western blotting (representative knockdown shown in Fig. 2E). This result was further validated by immunofluorescent staining for I477N myocilin in cells transfected with control or Grp94 siRNA. Grp94 knockdown reduced myocilin levels by ∼63% as compared with control cells after normalization to 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) signal (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these results suggested that Grp94, more than other candidate chaperones, was important for regulating mutant myocilin accumulation.

FIGURE 2.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of Grp94 regulates levels of I477N, but not wild type, myocilin. A and C, Western blot analysis of HEK cells conditionally over-expressing I477N myocilin (iI477N) (A) or wild type myocilin (iWT) (C) shows the intracellular levels of myocilin after siRNA-mediated knockdown of Hsp70, Hsp40, Cdc37, Hsp90β, and Grp94 using an anti-FLAG antibody. B and D, dot blots of media from HEK iI477N (B) or iWT (D) cells show levels of secreted myocilin after siRNA-mediated knockdown of Hsp70, Hsp40, Cdc37, Hsp90β, and Grp94 using an anti-FLAG antibody. E, Western blot analysis of cell lysates from HEK cells transfected with indicated siRNAs using respective antibodies as shown. Following transfection, cultures were maintained for 72 h to visualize optimal knockdown. GOI indicates gene of interest. F, confocal immunofluorescence microscopy of myocilin (red) in HEK iI477N cells following control or Grp94 siRNA transfection is shown. DAPI is shown in blue. Quantitation of myocilin intensity after normalization to DAPI stain showed a 63% reduction in I477N myocilin following Grp94 knockdown. Scale bar = 10 μm.

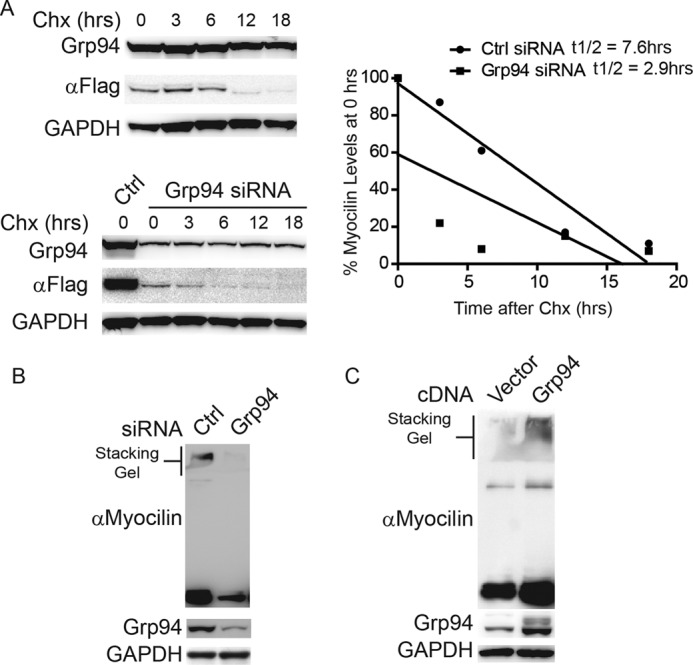

Grp94 Preserves Mutant Myocilin

Next, we determined whether Grp94 was involved in I477N myocilin protein turnover. Cyclohexamide chase experiments showed that the degradation rate of I477N myocilin increased ∼2.5 times following Grp94 knockdown (Fig. 3A). We also investigated whether Grp94 was influencing mutant myocilin solubility. This was based on previous work showing that myocilin mutants are insoluble as demonstrated by their partial retention in the stacking gel (7, 18). Western blotting of i477N cell lysates transfected with Grp94 siRNA showed decreased insoluble and soluble myocilin, as detected with a myocilin-specific antibody (Fig. 3B). In contrast, overexpression of Grp94 in iI477N cells caused both soluble and insoluble mutant myocilin to accumulate (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Grp94 preserves mutant myocilin. A, Western blot analysis of iI477N cell lysates transfected with control siRNA or Grp94 siRNA, treated with 50 μm cycloheximide, and harvested at the indicated time points. Half-life of I477N myocilin (t1/2) transfected with control siRNA was determined to be 7.6 h. Half-life of I477N myocilin transfected with Grp94 siRNA was 2.9 h. B, Western blot of HEK iI477N cell lysates transfected with control siRNA or Grp94 siRNA. Insoluble myocilin is shown in the stacking gel. Anti-myocilin antibody was used to confirm specificity of the effect. C, Western blot of HEK iI477N cell lysates transfected with vector or Grp94 cDNA. Insoluble myocilin is shown in the stacking gel. Anti-myocilin antibody was used to confirm specificity of the effect.

Selective Interaction between Grp94 and Mutant Myocilin

To confirm the selective interaction between Grp94 and mutant myocilin, co-IP assays were performed (Fig. 4). First, results from the stably transfected model demonstrate that the FLAG-tagged I477N myocilin binds to Grp94, whereas wild type myocilin does not, possibly due to its rapid secretion (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this finding, I477N myocilin also increases Grp94 expression (Fig. 4A). To determine whether Grp94 was indeed selectively interacting with a mutant myocilin species, we took advantage of the known properties of the HEK transient transfection myocilin model, in which wild type myocilin is secreted but mutant myocilin is not secreted (7, 18). Nevertheless, some mutant myocilin is still found in the detergent-soluble fraction, allowing us to directly compare the interaction between Grp94 and intracellular, soluble wild type or mutant myocilin (Fig. 4B). In this way, wild type and one of the most aggressive mutant myocilin species, P370L (32–34), were transiently transfected into HEK cells, and lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with myocilin antibody. As in the stably transfected model, wild type myocilin does not appear to interact with Grp94 despite its robust intracellular expression and is secreted as expected. By contrast, like I477N, the P370L myocilin variant did associate with Grp94 (Fig. 4B).

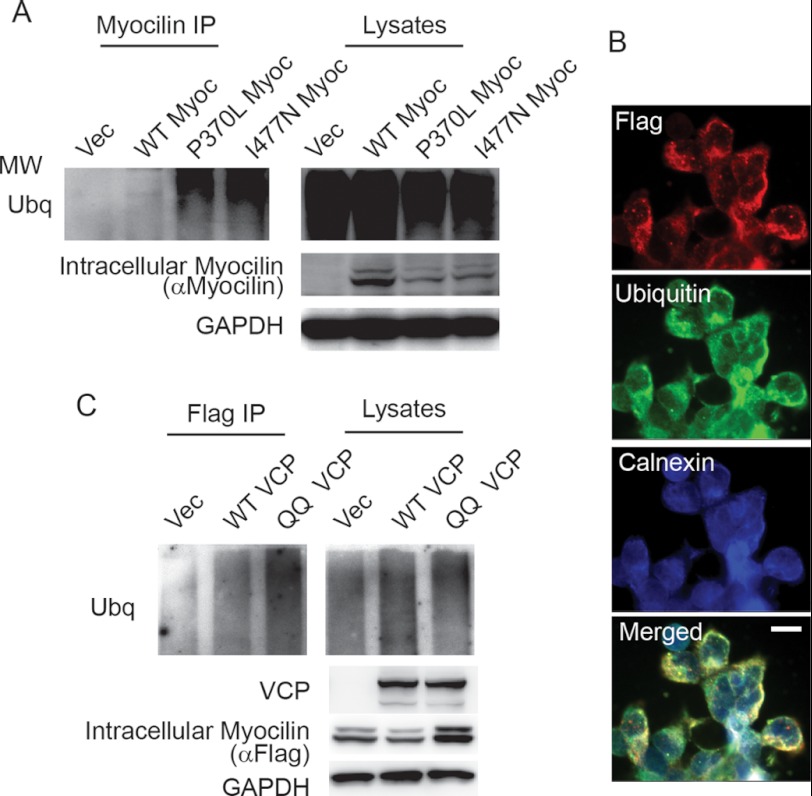

Grp94 Attempts to Triage Mutant Myocilin via ERAD

On the basis of the observed interaction between mutant myocilins and Grp94, we speculated that Grp94 was enlisting mutant myocilin for clearance by the traditional ERAD pathway, which begins with ubiquitination on the ER membrane and retro-translocation to the cytosol by the VCP/p97 complex for proteasomal degradation (35). The involvement of ERAD in clearing mutant myocilin was first investigated using the transient transfection model to detect ubiquitinated myocilin. Although a high level of total ubiquitinated protein was detected in all cell samples (as is typical following treatment with the proteasomal inhibitor epoxomicin which boosts the levels of ubiquitinated protein levels for detection purposes), only mutant I477N and P370L myocilin were ubiquitinated, as shown by myocilin immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A). Localization of ubiquitinated I477N mutant myocilin with the ER was validated by immunofluorescence imaging in the stably transfected model using calnexin and FLAG antibodies (Fig. 5B). In addition, involvement of the ERAD pathway was further confirmed for the stable cell line by evaluating the effects of wild type or dominant negative VCP/p97 (QQ VCP) transfection. This mutant form of VCP serves as a dominant negative, such that it inhibits retro-translocation of ERAD substrates (35). Immunoprecipitation revealed that QQ VCP expression resulted in higher levels of ubiquitinated mutant myocilin, whereas wild type VCP/p97 had minimal effect on ubiquitination (Fig. 5C). Notably, myocilin levels were somewhat higher in cells transfected with the QQ VCP when compared with cells transfected with wild type VCP/p97.

FIGURE 5.

Grp94 sequesters mutant myocilin for ERAD. A, co-immunopreciptation of myocilin from lysates transiently over-expressing wild type (WT), P370L, and I477N myocilin followed by Western blotting for ubiquitin, myocilin, and GAPDH. Ubiquitination of myocilin was only observed for the mutant myocilin species. Myocilin was detected with anti-myocilin antibody. MW indicates molecular weight. B, immunofluorescent labeling of HEK iI477N cells using anti-FLAG to detect myocilin (red), ubiquitin (green), and calnexin (blue) to indicate ER, showing that all three probes co-localize (Merged). Scale bar = 50 μm. C, Western blot for ubiquitin, myocilin, RGS-His (to detect VCP), and GAPDH of lysates and anti-FLAG co-immunoprecipitates from HEK iI477N cells transiently transfected with vector (Vec), wild type VCP (WT VCP), and dominant negative VCP (QQ VCP). Ubiquitination was enhanced in the presence of QQ VCP.

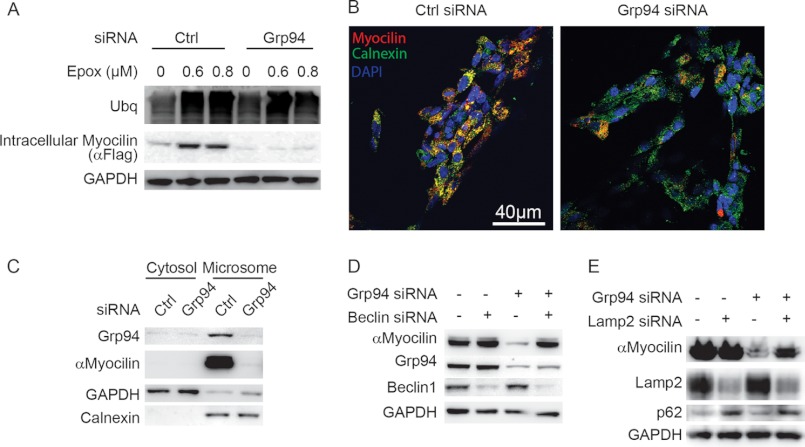

Grp94 Knockdown Enables an Alternative Autophagic Clearance Mechanism for Mutant Myocilin

To evaluate the extent of proteasomal involvement in degrading mutant myocilin upon Grp94 knockdown, the stable iI477N cell line was transfected with control or Grp94 siRNA and then treated with epoxomicin, a proteasome inhibitor. Although proteasome inhibition blocked the clearance of I477N myocilin under control conditions, surprisingly, there was no effect on clearance caused by Grp94 knockdown (Fig. 6A). The cellular location of mutant myocilin under conditions of Grp94 knockdown was further assessed by co-localization studies (Fig. 6B). Under control conditions, I477N myocilin co-localized with the ER chaperone calnexin (Fig. 6B), whereas under Grp94 knockdown conditions, myocilin co-localization with calnexin was diminished (Fig. 6B). We then turned to sub-cellular fractionation studies to clarify biochemically whether the localization of mutant myocilin was changing in response to Grp94 knockdown. As expected, in cells transfected with control siRNA, mutant myocilin was predominantly localized to the microsomal fraction (Fig. 6C). In cells transfected with Grp94 siRNA, mutant myocilin was reduced in the microsomal fraction with no subsequent increase in cytosolic levels, further confirming that an alternative clearance route for mutant myocilin was being activated by Grp94 depletion (Fig. 6C). We suspected that the alternative pathway being activated by Grp94 knockdown was autophagic. To determine if mutant myocilin was indeed being triaged toward autophagy after Grp94 depletion, siRNAs targeting Beclin-1 and Lamp2, two well characterized components of the autophagic pathway (36, 37), were transfected into cells along with Grp94 siRNA. Each of these has been used in cell culture extensively, including the HEK cell model used here (38–41). Indeed Beclin-1 knockdown abrogated mutant myocilin clearance caused by Grp94 depletion (Fig. 6D). Similar results were obtained when Lamp2 and Grp94 were simultaneously depleted (Fig. 6E). Autophagy suppression was confirmed by increases in p62 levels (42). Autophagy experiments were performed four times. These findings suggest that Grp94 attempts to triage I477N mutant myocilin for ERAD, but depletion of Grp94 activates a seemingly more efficient clearance route involving autophagy.

FIGURE 6.

Grp94 knockdown enables efficient autophagic degradation of mutant myocilin. A, Western blot analysis of HEK i477N cell lysates transfected with either control (Ctrl) or Grp94 siRNA and treated with indicated concentrations of the proteasomal inhibitor epoxomicin (Epox). Myocilin was detected with anti-FLAG antibody. B, confocal immunofluorescent imaging for myocilin with anti-FLAG (red) and calnexin (green) from HEK iI477N cells transfected with either control (Ctrl) or Grp94 siRNA. DAPI is shown in blue. Scale bar = 40 μm. C, Western blot of cytosolic and microsome sub-cellular fractions derived from iI477N cells following control (Ctrl) or Grp94 siRNA. Myocilin was detected with anti-myocilin antibody. D and E, Western blot analysis of HEK i477N cell lysates transfected with either control (Ctrl) or Grp94 siRNA and either Beclin-1 (D) or Lamp2 (E) siRNAs. Myocilin was detected with anti-myocilin antibody.

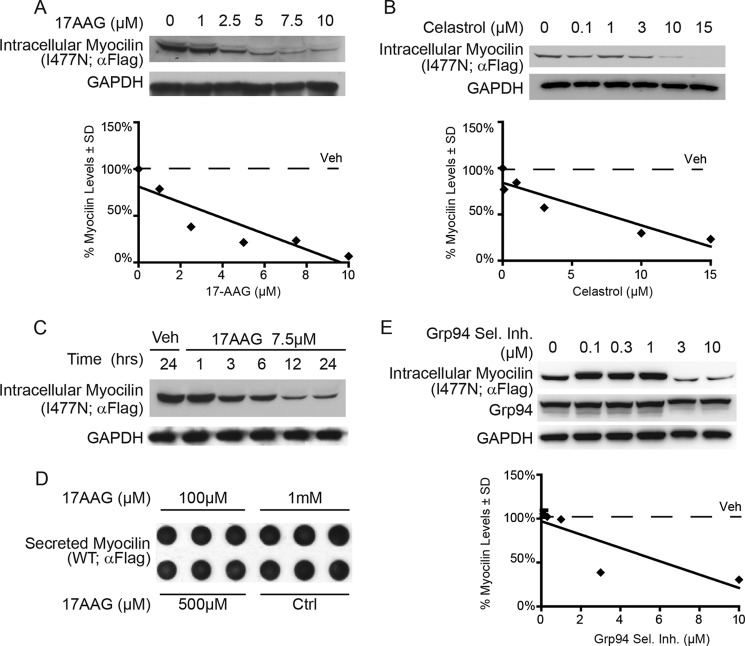

Pharmacological Targeting of ER Chaperones

Small-molecule inhibition of Hsp90, including Grp94, is in clinical development for a number of diseases (26, 43, 44), and because Grp94 sequesters mutant myocilin from ERAD and Grp94 knockdown enables efficient clearance, the effects of Hsp90 inhibitors were tested. The stable cell lines expressing wild type or I477N mutant myocilin were first treated with the general Hsp90/Grp94 inhibitors 17AAG or celastrol for 24 h, resulting in dose-dependent reductions of I477N mutant myocilin (Fig. 7, A and B). 17AAG facilitated reductions in I477N myocilin as soon as 3 h after treatment (Fig. 7C). As expected, levels of wild type myocilin were unaffected by 17AAG, even at a very high dosage (Fig. 7D). Similarly, a Grp94-selective inhibitor reduced I477N myocilin potently at 3 and 10 μm (Fig. 7E). Taken together, these results underscore the role of Grp94 in halting proper mutant myocilin degradation and support the idea that both general and selective Hsp90/Grp94 inhibitors could be effective therapies for glaucoma caused by mutations in myocilin.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of the Hsp90 chaperone complex reduces levels of the disease-causing I477N myocilin. A and B, Western blot of lysates from HEK iI477N cells treated with the indicated concentrations of the pan Hsp90/Grp94 inhibitors 17AAG (A) and celastrol (B) for 24 h. C, Western blot of lysates from HEK cells conditionally over-expressing I477N myocilin treated with 7.5 μm 17AAG or vehicle (Veh) and harvested at indicated time points. D, dot blot of the cell culture media of HEK iWT cells that were treated with the indicated concentration of 17AAG. E, Western blot of lysates from HEK iI477N cells and treated with indicated concentrations of a Grp94-selective inhibitor (Grp94 Sel. Inh.) for 24 h.

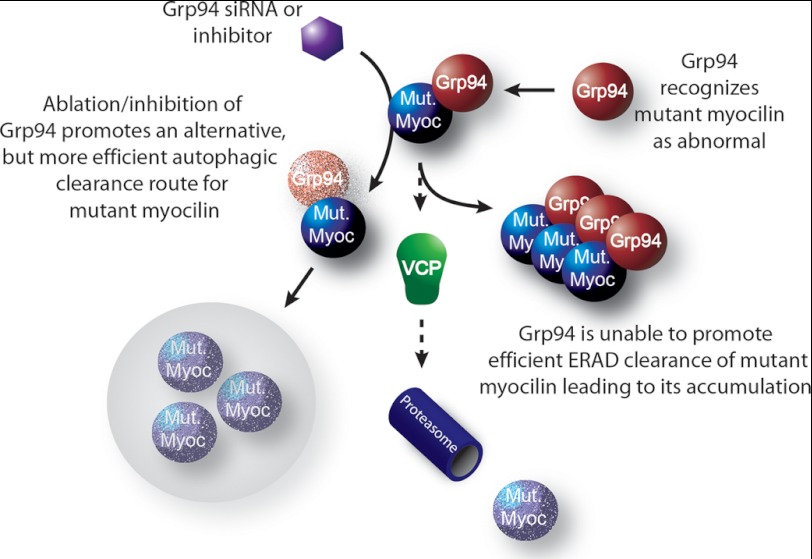

DISCUSSION

ER stress can lead to cell death and as such has been associated with a number of diseases (45). The protein quality control machinery can be overzealous in triaging mutant proteins for ERAD clearance (22, 46). For example, some mutant proteins that are folded in the ER, such as cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator associated with cystic fibrosis (46), enzymes implicated in lysosomal storage disorders (25, 47, 48), the vasopressin receptor associated with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (49), or rhodopsin associated with retinitis pigmintosa (50, 51), retain a native-like fold when studied in vitro; yet, their degradation via the ERAD system causes disease due to loss of function in the final cellular compartment. In these cases, significant efforts are in motion to rescue the mutant protein from degradation either by stabilizing it with a small molecule in the ER (52) or by manipulating the ER proteostasis network (53), with the end goal of enabling cellular trafficking and restoring activity or function in the desired cellular location.

The case of mutant myocilin represents the opposite paradigm for ER chaperone contribution to disease. The ER protein quality control program fails to degrade mutant myocilin because of an anomalous interaction with Grp94, which leads to pathogenic consequences (Fig. 8). The reason for aberrant Grp94 activity with mutant myocilin is not immediately clear, but it may be related to the ability of mutant myocilin to form amyloid fibrils (19), a nonnative aggregate structure that is highly resistant to degradation, a known feature of myocilin deposits (18). We propose that mutant myocilin amyloids clog the ERAD pathway during attempted triage, in a process that is triggered by its interaction with Grp94.

FIGURE 8.

Mutant myocilin becomes a client of Grp94 and is inefficiently processed by ERAD. Schematic shows that mutant myocilin becomes a Grp94 client and is triaged for ERAD. ERAD is not sufficient to prevent mutant myocilin accumulation. Knockdown or inhibition of Grp94 facilitates much more rapid clearance of mutant myocilin species via autophagy.

To date, efforts to devise a treatment strategy for myocilin glaucoma have focused on increasing the secretion of mutant myocilin from the ER by the use of chemical chaperones. For example, treating cells expressing mutant myocilins (7) or a Y437H myocilin transgenic mouse (21) with 4-phenylbutyrate have shown some promise in increasing secretion of mutant myocilin, which results in attenuated ER stress. This enhanced secretion has been anecdotally attributed to increased chaperone activity; however, our findings presented here suggest that increased chaperoning of mutant myocilin is at best ineffectual and at worst detrimental. Thus, combined with the fact that the olfactomedin domain itself is not stabilized by the presence of 4-phenylbutyrate (12), further investigation of the mechanism of action of 4-phenylbutyrate is warranted.

Whereas enhancing secretion is certainly a feasible strategy to treat myocilin glaucoma, the fact that myocilin knock-out mice and humans carrying premature stop codons within myocilin are asymptomatic raises the possibility that treatments aimed at simply ridding trabecular meshwork cells of mutant myocilin could be a viable therapeutic alternative. On the basis of our work, a novel strategy to steer mutant myocilin toward effective degradation would be to inhibit Grp94. Analogous inhibition of the paralog Hsp90 is under investigation as a therapeutic strategy for many diseases including cancers (44) and Alzheimer disease (26, 54). Importantly, depletion of Grp94, whereas lethal during development, has no obvious consequence in adults (55). Grp94 is structurally similar to cytosolic Hsp90, but lacks known co-chaperones and has very few known clients (56); the limited list includes immunoglobulins (57), integrins (58), and Toll-like receptors (59). Like these proteins, myocilin and in particular the olfactomedin domain that harbors 90% of all known disease-causing lesions (3) contains mainly β-strand secondary structure (12). The addition of mutant myocilin as a Grp94 client may assist in elucidating the specific role of Grp94 in vivo.

Finally, inhibition of the proteasome under conditions of Grp94 knockdown did not arrest I477N myocilin degradation. Instead, mutant myocilin was triaged toward an autophagic pathway involving Beclin-1 and Lamp2. This suggests that strategies diverting mutant myocilin to alternative clearance pathways, such as autophagy which is known to be more suitable for clearing multimeric-prone proteins (60, 61), are likely to be effective. The involvement of non-ERAD clearance pathways for mutant myocilin in the absence of chaperone manipulation has already been implicated as a result of its intracellular association with peroxisomes (62), exosomes (63, 64), and lysosomes (65). Here again, we show that when mutant myocilin is diverted away from ERAD by depleting Grp94, it associates with the autophagolytic system that is the pre-imminent cellular system for clearing protein aggregates. In sum, selective inhibition of Grp94, a very recent addition to the chemical biology repertoire available to regulate chaperones, is a strategy that holds considerable therapeutic promise for myocilin glaucoma.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health Grants R00AG031291 (to C. A. D.), R01NS073899 (to C. A. D.), and R01EY021205 (to R. L. L.). This work was also supported by the American Health Assistance Foundation.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation

- Grp94

- glucose-regulated protein 94

- Hsp90

- heat shock protein 90

- co-IP

- co-immunoprecipitation

- QQ VCP

- dominant negative VCP/p97.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kwon Y. H., Fingert J. H., Kuehn M. H., Alward W. L. (2009) Primary open-angle glaucoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1113–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fingert J. H., Héon E., Liebmann J. M., Yamamoto T., Craig J. E., Rait J., Kawase K., Hoh S. T., Buys Y. M., Dickinson J., Hockey R. R., Williams-Lyn D., Trope G., Kitazawa Y., Ritch R., Mackey D. A., Alward W. L., Sheffield V. C., Stone E. M. (1999) Analysis of myocilin mutations in 1703 glaucoma patients from five different populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 899–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Resch Z. T., Fautsch M. P. (2009) Glaucoma-associated myocilin: a better understanding but much more to learn. Exp. Eye Res. 88, 704–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alward W. L. (1998) Medical management of glaucoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 1298–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joe M. K., Sohn S., Hur W., Moon Y., Choi Y. R., Kee C. (2003) Accumulation of mutant myocilins in ER leads to ER stress and potential cytotoxicity in human trabecular meshwork cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 592–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu Y., Vollrath D. (2004) Reversal of mutant myocilin non-secretion and cell killing: implications for glaucoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 1193–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yam G. H., Gaplovska-Kysela K., Zuber C., Roth J. (2007) Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate acts as a chemical chaperone on misfolded myocilin to rescue cells from endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 1683–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gobeil S., Letartre L., Raymond V. (2006) Functional analysis of the glaucoma-causing TIGR/myocilin protein: integrity of amino-terminal coiled-coil regions and olfactomedin homology domain is essential for extracellular adhesion and secretion. Exp. Eye Res. 82, 1017–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vollrath D., Liu Y. (2006) Temperature sensitive secretion of mutant myocilins. Exp. Eye Res. 82, 1030–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang L., Zhuo Y., Liu B., Huang S., Hou F., Ge J. (2007) Pro370Leu mutant myocilin disturbs the endoplasm reticulum stress response and mitochondrial membrane potential in human trabecular meshwork cells. Mol. Vis. 13, 618–625 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gong G., Kosoko-Lasaki O., Haynatzki G. R., Wilson M. R. (2004) Genetic dissection of myocilin glaucoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, R91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burns J. N., Orwig S. D., Harris J. L., Watkins J. D., Vollrath D., Lieberman R. L. (2010) Rescue of glaucoma-causing mutant myocilin thermal stability by chemical chaperones. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 477–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burns J. N., Turnage K. C., Walker C. A., Lieberman R. L. (2011) The stability of myocilin olfactomedin domain variants provides new insight into glaucoma as a protein misfolding disorder. Biochemistry 50, 5824–5833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gould D. B., Reedy M., Wilson L. A., Smith R. S., Johnson R. L., John S. W. (2006) Mutant myocilin nonsecretion in vivo is not sufficient to cause glaucoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 8427–8436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lam D. S., Leung Y. F., Chua J. K., Baum L., Fan D. S., Choy K. W., Pang C. P. (2000) Truncations in the TIGR gene in individuals with and without primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 1386–1391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carbone M. A., Ayroles J. F., Yamamoto A., Morozova T. V., West S. A., Magwire M. M., Mackay T. F., Anholt R. R. (2009) Overexpression of myocilin in the Drosophila eye activates the unfolded protein response: implications for glaucoma. PLoS One 4, e4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zode G. S., Kuehn M. H., Nishimura D. Y., Searby C. C., Mohan K., Grozdanic S. D., Bugge K., Anderson M. G., Clark A. F., Stone E. M., Sheffield V. C. (2011) Reduction of ER stress via a chemical chaperone prevents disease phenotypes in a mouse model of primary open angle glaucoma. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3542–3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou Z., Vollrath D. (1999) A cellular assay distinguishes normal and mutant TIGR/myocilin protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2221–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Orwig S. D., Perry C. W., Kim L. Y., Turnage K. C., Zhang R., Vollrath D., Schmidt-Krey I., Lieberman R. L. (2012) Amyloid fibril formation by the glaucoma-associated olfactomedin domain of myocilin. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 242–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jia L. Y., Gong B., Pang C. P., Huang Y., Lam D. S., Wang N., Yam G. H. (2009) Correction of the disease phenotype of myocilin-causing glaucoma by a natural osmolyte. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 3743–3749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zode G. S., Bugge K. E., Mohan K., Grozdanic S. D., Peters J. C., Koehn D. R., Anderson M. G., Kardon R. H., Stone E. M., Sheffield V. C. (2012) Topical ocular sodium 4-phenylbutyrate rescues glaucoma in a myocilin mouse model of primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 1557–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meusser B., Hirsch C., Jarosch E., Sommer T. (2005) ERAD: the long road to destruction. Nature Cell Biol. 7, 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eletto D., Dersh D., Argon Y. (2010) GRP94 in ER quality control and stress responses. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farinha C. M., Amaral M. D. (2005) Most F508del-CFTR is targeted to degradation at an early folding checkpoint and independently of calnexin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5242–5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ron I., Horowitz M. (2005) ER retention and degradation as the molecular basis underlying Gaucher disease heterogeneity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2387–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dickey C. A., Kamal A., Lundgren K., Klosak N., Bailey R. M., Dunmore J., Ash P., Shoraka S., Zlatkovic J., Eckman C. B., Patterson C., Dickson D. W., Nahman N. S., Jr., Hutton M., Burrows F., Petrucelli L. (2007) The high-affinity HSP90-CHIP complex recognizes and selectively degrades phosphorylated tau client proteins. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 648–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joe M. K., Tomarev S. I. (2010) Expression of myocilin mutants sensitizes cells to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis: implication for glaucoma pathogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2880–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jinwal U. K., Miyata Y., Koren J., 3rd, Jones J. R., Trotter J. H., Chang L., O'Leary J., Morgan D., Lee D. C., Shults C. L., Rousaki A., Weeber E. J., Zuiderweg E. R., Gestwicki J. E., Dickey C. A. (2009) Chemical manipulation of hsp70 ATPase activity regulates τ stability. J. Neurosci. 29, 12079–12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abisambra J. F., Jinwal U. K., Suntharalingam A., Arulselvam K., Brady S., Cockman M., Jin Y., Zhang B., Dickey C. A. (2012) DnaJA1 antagonizes constitutive Hsp70-mediated stabilization of τ. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 653–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abisambra J. F., Blair L. J., Hill S. E., Jones J. R., Kraft C., Rogers J., Koren J., 3rd, Jinwal U. K., Lawson L., Johnson A. G., Wilcock D., O'Leary J. C., Jansen K., Muschol M., Golde T. E., Weeber E. J., Banko J., Dickey C. A. (2010) Phosphorylation dynamics regulate Hsp27-mediated rescue of neuronal plasticity deficits in tau transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 30, 15374–15382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muchowski P. J., Wacker J. L. (2005) Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ge J., Zhuo Y., Guo Y., Ming W., Yin W. (2000) Gene mutation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma in a pedigree in China. Chin. Med. J. 113, 195–197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rozsa F. W., Shimizu S., Lichter P. R., Johnson A. T., Othman M. I., Scott K., Downs C. A., Nguyen T. D., Polansky J., Richards J. E. (1998) GLC1A mutations point to regions of potential functional importance on the TIGR/MYOC protein. Mol. Vis. 4, 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adam M. F., Belmouden A., Binisti P., Brézin A. P., Valtot F., Béchetoille A., Dascotte J. C., Copin B., Gomez L., Chaventré A., Bach J. F., Garchon H. J. (1997) Recurrent mutations in a single exon encoding the evolutionarily conserved olfactomedin-homology domain of TIGR in familial open-angle glaucoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 2091–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ye Y., Meyer H. H., Rapoport T. A. (2001) The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature 414, 652–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liang X. H., Jackson S., Seaman M., Brown K., Kempkes B., Hibshoosh H., Levine B. (1999) Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 402, 672–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tanaka Y., Guhde G., Suter A., Eskelinen E. L., Hartmann D., Lüllmann-Rauch R., Janssen P. M., Blanz J., von Figura K., Saftig P. (2000) Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature 406, 902–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu H., Wang P., Song W., Sun X. (2009) Degradation of regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1) is mediated by both chaperone-mediated autophagy and ubiquitin proteasome pathways. FASEB J. 23, 3383–3392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alvarez-Erviti L., Rodriguez-Oroz M. C., Cooper J. M., Caballero C., Ferrer I., Obeso J. A., Schapira A. H. (2010) Chaperone-mediated autophagy markers in Parkinson disease brains. Arch. Neurol. 67, 1464–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vogiatzi T., Xilouri M., Vekrellis K., Stefanis L. (2008) Wild type α-synuclein is degraded by chaperone-mediated autophagy and macroautophagy in neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23542–23556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen Y., McMillan-Ward E., Kong J., Israels S. J., Gibson S. B. (2008) Oxidative stress induces autophagic cell death independent of apoptosis in transformed and cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 15, 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bjørkøy G., Lamark T., Pankiv S., Øvervatn A., Brech A., Johansen T. (2009) Monitoring autophagic degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods Enzymol. 452, 181–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kamal A., Boehm M. F., Burrows F. J. (2004) Therapeutic and diagnostic implications of Hsp90 activation. Trends Mol. Med. 10, 283–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Neckers L., Workman P. (2012) Hsp90 molecular chaperone inhibitors: are we there yet? Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 64–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tabas I., Ron D. (2011) Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 184–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang X., Venable J., LaPointe P., Hutt D. M., Koulov A. V., Coppinger J., Gurkan C., Kellner W., Matteson J., Plutner H., Riordan J. R., Kelly J. W., Yates J. R., 3rd, Balch W. E. (2006) Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell 127, 803–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liou B., Kazimierczuk A., Zhang M., Scott C. R., Hegde R. S., Grabowski G. A. (2006) Analyses of variant acid β-glucosidases: effects of Gaucher disease mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4242–4253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fan J. Q., Ishii S., Asano N., Suzuki Y. (1999) Accelerated transport and maturation of lysosomal α-galactosidase A in Fabry lymphoblasts by an enzyme inhibitor. Nat. Med. 5, 112–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morello J. P., Salahpour A., Laperrière A., Bernier V., Arthus M. F., Lonergan M., Petäjä-Repo U., Angers S., Morin D., Bichet D. G., Bouvier M. (2000) Pharmacological chaperones rescue cell-surface expression and function of misfolded V2 vasopressin receptor mutants. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 887–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu X., Garriga P., Khorana H. G. (1996) Structure and function in rhodopsin: correct folding and misfolding in two point mutants in the intradiscal domain of rhodopsin identified in retinitis pigmentosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4554–4559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Garriga P., Liu X., Khorana H. G. (1996) Structure and function in rhodopsin: correct folding and misfolding in point mutants at and in proximity to the site of the retinitis pigmentosa mutation Leu-125↓Arg in the transmembrane helix C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4560–4564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rajan R. S., Tsumoto K., Tokunaga M., Tokunaga H., Kita Y., Arakawa T. (2011) Chemical and pharmacological chaperones: application for recombinant protein production and protein folding diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Balch W. E., Morimoto R. I., Dillin A., Kelly J. W. (2008) Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319, 916–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luo W., Dou F., Rodina A., Chip S., Kim J., Zhao Q., Moulick K., Aguirre J., Wu N., Greengard P., Chiosis G. (2007) Roles of heat-shock protein 90 in maintaining and facilitating the neurodegenerative phenotype in tauopathies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9511–9516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maynard J. C., Pham T., Zheng T., Jockheck-Clark A., Rankin H. B., Newgard C. B., Spana E. P., Nicchitta C. V. (2010) Gp93, the Drosophila GRP94 ortholog, is required for gut epithelial homeostasis and nutrient assimilation-coupled growth control. Dev. Biol. 339, 295–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Marzec M., Eletto D., Argon Y. (2012) GRP94: an HSP90-like protein specialized for protein folding and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 774–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Melnick J., Dul J. L., Argon Y. (1994) Sequential interaction of the chaperones BiP and GRP94 with immunoglobulin chains in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 370, 373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu Y., Sweet D. T., Irani-Tehrani M., Maeda N., Tzima E. (2008) Shc coordinates signals from intercellular junctions and integrins to regulate flow-induced inflammation. J. Cell Biol. 182, 185–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morales C., Wu S., Yang Y., Hao B., Li Z. (2009) Drosophila glycoprotein 93 is an ortholog of mammalian heat shock protein gp96 (grp94, HSP90b1, HSPC4) and retains disulfide bond-independent chaperone function for TLRs and integrins. J. Immunol. 183, 5121–5128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Koga H., Cuervo A. M. (2010) Chaperone-mediated autophagy dysfunction in the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 43, 29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Santambrogio L., Cuervo A. M. (2011) Chasing the elusive mammalian microautophagy. Autophagy 7, 652–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shepard A. R., Jacobson N., Millar J. C., Pang I. H., Steely H. T., Searby C. C., Sheffield V. C., Stone E. M., Clark A. F. (2007) Glaucoma-causing myocilin mutants require the peroxisomal targeting signal-1 receptor (PTS1R) to elevate intraocular pressure. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 609–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Perkumas K. M., Hoffman E. A., McKay B. S., Allingham R. R., Stamer W. D. (2007) Myocilin-associated exosomes in human ocular samples. Exp. Eye Res. 84, 209–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hardy K. M., Hoffman E. A., Gonzalez P., McKay B. S., Stamer W. D. (2005) Extracellular trafficking of myocilin in human trabecular meshwork cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28917–28926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liton P. B., Lin Y., Gonzalez P., Epstein D. L. (2009) Potential role of lysosomal dysfunction in the pathogenesis of primary open angle glaucoma. Autophagy 5, 122–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]