Background: HB9 is highly expressed in translocation t(7;12) positive infant AML.

Results: HB9 binds to the PTGER2 promoter, down-regulates PTGER2 gene expression and subsequently represses cAMP synthesis in hematopoietic cells.

Conclusion: Expression of HLXB9 represses PTGER2 mediated signaling.

Significance: First molecular report of HB9-dependent target gene regulation in hematopoietic cells.

Keywords: Gene Regulation, Homeobox, Leukemia, Oncogene, Promoters, Transcription Factors

Abstract

The transcription factor HB9, encoded by the homeobox gene B9 (HLXB9), is involved in the development of pancreatic beta- and motor neuronal cells. In addition, HLXB9 is recurrently rearranged in young children with acute myeloid leukemia characterized by a chromosomal translocation t(7;12)-HLXB9/TEL and concomitant high expression of the unrearranged, wild-type HLXB9 allele. However, target genes of HB9 in hematopoietic cells are not known to date. In this study, we used ChIP-on-chip analysis together with expression profiling and identified PTGER2 (prostaglandin E receptor 2) as a target gene of HB9 in a hematopoietic cell line. The functional HB9 homeodomain as well as the HB9 binding domain within the PTGER2 promoter are essential for binding of HB9 to the PTGER2 promoter region and down-regulation of PTGER2 expression. Functionally, HB9 conducted down-regulation of PTGER2 results in a reduced content of intracellular cAMP mobilization and furthermore the decreased PTGER2 gene expression is valid in bone marrow cells from translocation t(7;12) positive patients.

Among the primary and secondary target genes of HB9 in the myeloid cell line HL60, 78% of significantly regulated genes are down-regulated, indicating an overall repressive function of HB9. Differentially regulated genes were preferentially confined to pathways involved in cell-adhesion and cell-cell interactions, similar to the gene expression footprint of HLXB9-expressing cells from t(7;12) positive patients.

Introduction

HLXB9, also known as MNX1 (motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1) belongs to the family of homeobox genes and is located on chromosome 7q36 (1). It is composed of three exons comprising 1206 bp and encodes the 401-amino acid transcription factor HB9. The homeobox encodes for the homeodomain, a well described DNA-binding domain in many transcription factors. The homeodomain is structured in three helices, which are involved in DNA interaction (2), and is highly homologous to a homeodomain consensus sequence (1). HB9 harbors a polyalanine stretch (16×) and two glycine stretches (7× and 5×) as additional structural features, but a functional impact on DNA-binding or gene regulation has not been experimentally shown yet.

In mice, HB9 is a central mediator of cellular differentiation in pancreatic tissue and motor neurons during embryonic development (3–5). It is indispensable for the initiation of the dorsal pancreatic program, and hence, HB9-deficient mice show characteristic agenesis of the dorsal but not the ventral pancreatic lobe (3). Motor neuron differentiation and their proper specification also occurs in early embryonic development (embryonic day 8.5), and HB9 is specifically important to distinguish between motor neuron and interneuron identity (5).

In humans, a dominant loss-of-function mutation in the HLXB9 gene results in sacral agenesis, concomitant anorectal, and urogenital malformations, altogether a well described symptom complex named Currarino syndrome (6). Moreover, HLXB9 expression is described in colorectal cancer tissue and hepatocellular carcinoma (7, 8). Other than its role in differentiation of tissues from the endoderm and ectoderm, the function of HB9 in derivates from the mesenchyme, like hematopoietic cells, is largely unknown. Conflicting reports exist about the expression of HLXB9 in hematopoietic stem cells. Deguchi and Kehrl (9) reported HLXB9 expression in CD34-enriched and unfractionated bone marrow cells. However, we and others (10) did not observe HLXB9 expression in healthy CD34+ bone marrow cells. The only reports attributing a functional role to HLXB9 expression in hematopoiesis come from infants with acute myeloid leukemia characterized by a chromosomal translocation t(7;12)-HLXB9/TEL in their leukemic cells (10–13). All patients show an aberrantly high expression of the non-rearranged HLXB9 allele in the leukemic cells (10). Of note, a fusion HLXB9/TEL mRNA transcript is not always detected in blast cells of all translocation t(7;12) positive patients as a result of the genomic heterogeneity of the 7q36 breakpoint (10, 11). With a three-year event-free-survival of 0%, this leukemia entity has a dismal prognosis (14–17). We previously characterized the gene expression profile of translocation t(7;12) positive leukemic blast cells. Functional annotation analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes can be attributed to pathways involved in cell adhesion or closely related processes (17). Based on its high homology to other homeodomain proteins, HB9 likely acts as a transcription factor but neither its DNA-binding properties nor its target genes in hematopoietic cells have been identified thus far. In our present work, we used global, genome-wide approaches to identify both primary and secondary target genes of HB9 in hematopoietic cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

HL60 cells were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mm glutamine (Invitrogen). HL60 cells carrying the pMC plasmid were cultured in the presence of 0.5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). All cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. A codon optimized cDNA of human HLXB9, fused with an N-terminal FLAG tag, was purchased from GENEART (Regensburg, Germany). The mutant HLXB9, lacking part of the homeodomain, was accomplished by overlap extension PCR (see supplemental Fig. S1, A and B, for mutation design and primer sequences). Constructs were inserted into the bicistronic expression vector pMC-puro (18). HL60 cells were split the day prior electroporation, so cells are in log-phase during electroporation. For electroporation 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in 500 μl of RPMI without supplements and mixed with 10 μg of linearized vector DNA. Electroporation was carried out in an EPI 2500 electroporator (Dr. Fischer, Heidelberger, Germany) at 400 V and 10 ms. After 24 h, growth medium was replaced and supplemented with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin. Positive cells were selected for at least 4 weeks. Cells are referred to as HL60(HB9) and HL60(HB9(del)). Cells that were transfected with the empty pMC vector serve as negative control (HL60(control)).

ChIP-on-chip

ChIP-on-chip analysis was accomplished for HL60(HB9) and HL60(control) cells in three biological replicates defined by distinct cell culture passages. ChIP-on-chip was carried out with the SimpleChIP enzymatic chromatin IP kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, chromatin from 40 × 106 fixed HL60 cells were enzymatically digested to a size range of 150–900 bases with the use of a micrococcal nuclease. Cell membranes were disrupted by sonification with a UP 100H sonifier (Hielscher, Teltow, Germany) in a volume of 500 μl for three times 10 s and 60% energy output. Solubilized chromatin from 32 × 106 cells was immunoprecipitated overnight with the use of 100 μl anti-FLAG® M2 agarose beads. Washing, elution, and purification of the DNA was done according to manufacturer's instructions, followed by whole genome amplification with the use of the “GenomePlex Complete whole genome amplification kit” (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions except an additional fragmentation step. Labeling of the target DNA (Cy5) and input material (Cy3) as well as co-hybridization of the target sample and the corresponding input onto 385K RefSeq Promoter Arrays hg18 was done by NimbleGen systems. The 385K RefSeq Promoter Array contains promoter regions of all known RefSeq genes, which extend 2200 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the transcription start site.

Data were extracted and analyzed according to standard operating procedures by NimbleGen Systems. Scaled log2-ratios (Cy5/Cy3) were calculated for each feature on the array and were used for peak detection. Each peak was assigned a false discovery rate (FDR).3 Only peaks with an FDR score ≥ 0.05 were considered as protein binding sites. Signal map software was provided by NimbleGen systems and was used to visualize the array peaks. Functional annotations were performed using the program EGAN (19), which uses a standard one-tailed Fisher's exact (hypergeometric) test for enrichment calculations of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways and Gene Ontology terms.

Affymetrix Expression Arrays and Data Analysis

Gene expression analysis was accomplished for HL60(HB9) cells and HL60(control) cells in three biological replicates. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and utilized for synthesis of single-stranded cDNA. cDNA synthesis and amplification as well as fragmentation and labeling was done according to the manual GeneChip WT Sense Target Labeling Assay offered by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA). Labeled cDNA was hybridized onto human GeneChip® 1.0 ST Arrays. The raw .cel files were read-in using the R-package aroma.affymetrix. The arrays were normalized using the robust multiarray average method (20) from the same package. This method consists of three steps. First, a background adjustment is carried out, correcting the probe intensities for background noise array by array. In the second step, the arrays are quantile-normalized to impose the same empirical distribution of intensities to each array. To get gene-level summaries for each gene, the probes are summarized based on a multiarray model using the median polish algorithm in the third step. The subsequent analysis steps were performed in R using the limma package (21). To assess differential gene expression this package implements an empirical Bayes approach. This method borrows information from the ensemble of all genes to estimate the significance of single genes. The gene-wise tests are based on moderated t-statistics in which posterior standard deviations are used in place of ordinary standard deviations. The process yields shrinkage of the gene-wise sample variances toward a common value, resulting in more stable inference compared with ordinary t tests when the number of arrays is small. For control of the false discovery rate, the resulting p values were adjusted according to Benjamini and Hochberg's method. The heat maps used to visualize the most differentially expressed genes were generated using the heatmap.2 function from R-package g plots. The expression values were centered and scaled row-wise.

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCRs were carried out using SYBR green PCR mix and an ABI PRISM® 7900 HT real-time machine (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). All primers were purchased from Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany).

Amplified ChIP DNA as well as the corresponding input was used for validation of genomic regions detected by the promoter array analysis. Primers were designed to amplify 170–200-bp fragments of selected regions detected in the array analysis. ΔCt was calculated for each sample by subtracting the Ct value of the corresponding input material from the Ct value of the immunoprecipitated sample. The relative enrichment was calculated by 2−ΔCt. Genome locations of enriched promoter sequences as well as primer sequences are given in supplemental Fig. S2.

For validation of differentially expressed genes in HL60(HB9) and HL60(control) cells, RNA (Qiagen RNAeasy kit, Hilden, Germany) and cDNA (Qiagen QuantiTect, Hilden, Germany) was synthesized according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers were designed to amplify 170–200-bp fragments of selected target cDNA and encompass an exon-exon boundary to impede amplification of genomic DNA. ΔCt was calculated by normalization to β-actin, and relative expression was calculated by 2−ΔCt. Subsequent statistical examinations were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Primary bone marrow or peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from the leukemia laboratory (Giessen, Germany), and informed consent was obtained from all families. Criteria for the patient samples were diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia within the first two years and a blast content > 60%. RNA was isolated using TRIzol according to the manufacturer's instructions und used for cDNA synthesis. ΔCt was calculated by normalization to β-actin, and relative expression was calculated by 2−Ct.

Reporter Assay

Promoterless firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL4.10 and Renilla luciferase control vector pGL4.73 were purchased from Promega GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). Different fragments of the PTGER2 promoter were cloned into pGL4.10 vector. Fragment A (pGL4.10-A-) contains 3.2 kb (nucleotide residues −3008 to +225, transcription start site = 1) of the PTGER2 promoter region, including the HB9 binding region (nucleotide residues −2103 to −353, the transcription start site = 1) detected in the ChIP-on-chip analysis. Fragment B (pGL4.10-B-) serves as a negative control and contains a 1.7-kb-long region (nucleotide residues −3865 to −2106, the transcription start site = 1) upstream of the detected binding site. HL60(control), HL60(HB9), and HL60(HB9(del)) cells were transiently co-transfected with pGL4.10-A- or pGL4.10-B- and pGL4.73 using Amaxa Nucleofector technology (Lonza Cologne GmbH, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell extracts were assayed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activity using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Firefly relative light unit values were normalized to Renilla relative light unit values to compensate transfection and cell count variability. Additionally, relative light unit values were normalized to background light units.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell extracts were applied to 10% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis), transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with an HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated mouse anti-FLAG antibody (A8592, Sigma-Aldrich) or mouse anti-GAPDH (sc-32233, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as a loading control. The HRP-conjugated antibody goat anti-mouse IgG (sc-32233, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a secondary antibody. For detection of PTGER2, an anti-EP2 receptor antibody (EP2 receptor polyclonal antibody, Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) in addition with an HRP-conjugated antibody goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) was used. Membranes were revealed using chemiluminescence SuperSignal West Pico solution (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

cAMP Enzyme Immunoassay

HL60(control), HL60(HB9), and HL60(HB9(del)) cells were split the day prior to cAMP measurement. For the immunoassay, 3 × 106 cells were induced with 10 μm butaprost for 20 min in growth medium at 37 °C. Addition of the same concentration of the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide serves as a control sample. 6 × 105 cells were induced with 5 μm PGE2 or ethanol as a solvent, respectively. Lysis and intracellular cAMP content was measured with the cAMP Biotrak enzyme immunoassay system (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions (chapter 7.3). pmol cAMP per well was calculated and normalized to the solvent control. Each measurement was performed in three independent replicates.

RESULTS

Identification of HB9 Target Genes Using ChIP-on-chip

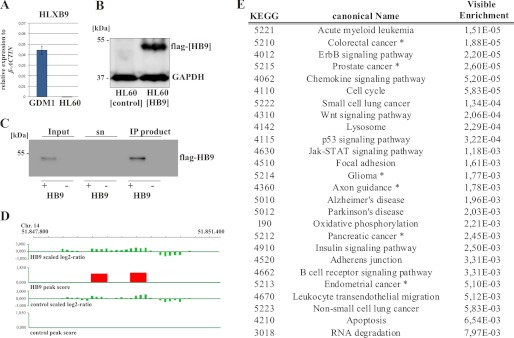

Myeloid hematopoietic cells are in general devoid of HLXB9 expression. Solely blast cells from translocation t(7;12) positive patients as well as the acute myeloid leukemia cell line GDM1 (22) aberrantly overexpress HLXB9. To study the effect of HLXB9 expression in myeloid cells, we chose the HL60 (23) cell line system, which lacks expression of HLXB9 as shown by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1A). We stably transfected HL60 cells with the pMC(HB9) vector or an empty vector control. Production of the FLAG-tagged HB9 protein was validated in regular intervals (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

HB9 ChIP-on-chip analysis. A, endogenous expression of HLXB9 in the HL60 and GDM1 cell line was measured by qRT-PCR. Values were normalized to β-actin. The cell line GDM1 served as a positive control (n = 3). B, immunoblot shows the presence of HB9 protein in the pMC-HLXB9 transfected HL60 cells. C, immunoblot of the immunoprecipitated samples from HL60 cells transfected with either pMC-HLXB9 or the empty vector pMC as a negative control. Indicated are the input material, the supernatant (sn) and the IP product. D, binding pattern of HB9 to the PTGER2 promoter region. Indicated is the scaled log2 ratio from HL60(HB9) and HL60(control) cells. The red peak represents a FDR < 0.05. E, 660 target genes of HB9 are conducted to an EGAN pathway analysis. Listed is a subset of significantly enriched pathways; an asterisk marks tissues with endogenous HLXB9 expression.

Binding of HB9 to promoter regions was studied using ChIP-on-chip analysis. ChIP experiments were performed in three biological replicates comparing HL60(HB9) and HL60(control) cells. HB9-bound chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG affinity beads. We subsequently validated recovery and effectiveness of the HB9 immunoprecipitation as illustrated in a Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C). Both the ChIP sample and the corresponding input material were hybridized onto 385K RefSeq Promoter Arrays. These arrays contain promoter regions of all known RefSeq genes, which extend 2200 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the transcription start site.

Each potential binding site was calculated from the ratio of the sample to the input material and was assigned an FDR. Representative for other target genes we illustrate two binding sites (FDR ≤ 0.05) within the promoter region of PTGER2 of the HB9-immunoprecipitated sample (Fig. 1D). This region contains several “ATTA” motifs, the typical recognition sequence of the homeodomain, particularly of the third helix (2). No detectable binding within this region was observed in the HL60(control) sample. Promoters with a significant binding peak ≤ 0.05 were determined for each biological replicate and the HL60(HB9) cells were compared with HL60 control cells. Only those promoter regions, which showed a significant binding pattern in the HB9 sample but not in the control samples, were graded as real target sites. In that way, we observed enriched promoter sequences for 1279, 1648, and 728 genes in each of the individual experiments. 660 genes were shared by at least two replicates and 114 were shared by all three. For subsequent analysis, we classified a peak as a HB9 binding site if the region was bound in at least two of three independent experiments. Functional annotation of these 660 target genes was performed using the EGAN software. Target genes could be attributed to significantly enriched pathways which play crucial roles in the development of cancer, e.g. acute myeloid leukemia, ErbB signaling, Wnt signaling, p53 signaling, and Jak-Stat signaling. Pathways involved in colorectal, prostate, and pancreatic cancers as well as in glioma are marked with an asterisk and are related to tissues with physiological HLXB9 expression (Fig. 1E).

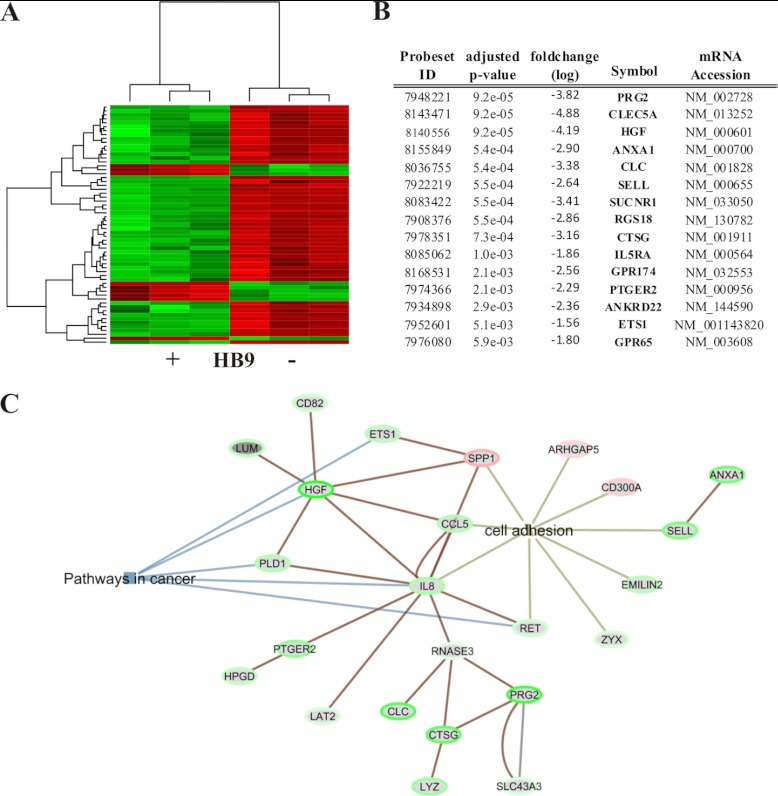

HLXB9 Acts Predominantly as a Transcriptional Repressor

We next compared the gene expression profiles of HL60(HB9) and HL60(control) cells using Affymetrix Gene Arrays. The microarray analysis identified 81 differentially expressed genes with an adjusted p value ≤ 0.05. 63 (78%) of differentially expressed genes are down-regulated representing a predominant repressive function of HB9 (Fig. 2A). 15 genes with the lowest p value are listed in Fig. 2B and are down-regulated in the presence of HB9. Proteoglycan 2 (PRG2), C-type lectin domain family 5, member A (CLEC5A), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) show the highest fold change. All differentially expressed genes (adjusted p value ≤ 0.05) were subjected to EGAN annotation analysis. Genes attributed to cancer-related pathways and to the gene ontology term cell adhesion are indicated in a network visualization. Edges show genes, with previously published relationships (Fig. 2C). The gene ontology term cell adhesion is highly enriched.

FIGURE 2.

Gene expression profiling of HL60 cells transfected with HLXB9. A, the heatmap illustrates differentially expressed genes of HL60(HB9) and HL60(control) cells (n = 3) with a significant altered expression of p < 0.05. Green indicates genes down-regulated in HL60(HB9) cells; red indicates up-regulated genes. B, listed are the top 15 differentially expressed genes sorted by their p value. The Affymetrix probe set ID, the fold change (log), the gene symbol, and the mRNA accession nos. are listed as well. C, EGAN network representation of significantly regulated genes, which could be attributed to the KEGG term “pathways in cancer” (blue edges) and to the gene ontology process cell adhesion (light brown edges). Related genes are connected by a dark brown line.

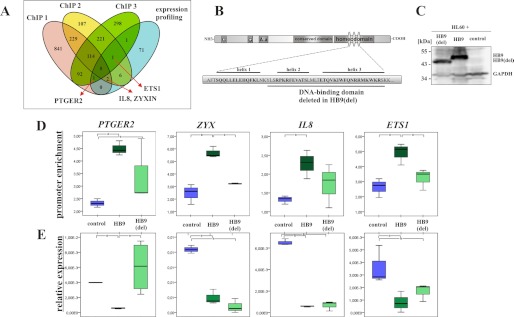

The HB9 Homeodomain Is Essential for Interaction with the PTGER2 Promoter and PTGER2 Gene Regulation

Combined gene expression analysis and ChIP-on-chip experiments revealed four target genes: PTGER2, IL8 (interleukin-8), ZYX (zyxin), and ETS1 (v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1) (Fig. 3A). Next, we addressed the role of a functional homeodomain for the HB9-DNA interaction and target gene regulation. We performed mutagenesis of HLXB9 and deleted the corresponding part of the HLXB9 homeobox, which encodes for 35 amino acids forming the potential helices two and three, which are supposed to be involved in DNA interaction (Fig. 3B). The HLXB9 mutant (HLXB9(del)) was cloned in the expression vector pMC and stably transfected in HL60 cells. The mutated protein has a four kDa lower molecular mass compared with the wild-type HB9, and both forms can be easily distinguished by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3C). The ability of wild-type HB9 and HB9(del) to bind to the promoter regions of PTGER2, ZYX, IL8, and ETS1 was analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative PCR using primers spanning the promoter sequences detected in our prior ChIP-on-chip analysis (Fig. 3D, supplemental Fig. S2). We succeeded to validate our promoter array data and observed a significant enrichment (p ≤ 0.05) of the promoter regions of the four target genes in the HB9 expressing cells compared with the HB9(control) sample using qPCR. Consistently, a lower or no enrichment was observed for the promoter regions of the four target genes in the HB9(del) expressing cells compared with the HB9 sample. No enrichment for HB9 and HB9(del) was observed for the myoglobin exon 2 region, which serves as a negative control (supplemental Fig. S1C).

FIGURE 3.

DNA interaction and gene regulation by HB9 and HB9(del). A, Venn diagram showing the number of genes bound by HB9 in three independent experiments and the overlap with 81 significantly differentially expressed genes. B, schematic representation of the protein structure of HB9. The homeodomain is structured in three helices, which are involved in DNA binding. Underlined amino acids are deleted in HB9(del). C, immunoblot shows a representative band for HB9(del), which runs with a 4-kDa lower molecular mass than the full-length HB9. GAPDH serves as a loading control. D, binding of HB9 and HB9(del) to the promoter regions of PTGER2, ZYX, IL8, and ETS1. Given are means and S.D. of three biological replicates; *, p ≤ 0.05. Enrichment of promoter regions is normalized to the corresponding input. E, expression of PTGER2, ZYX, IL8, and ETS1 in HL60(control), HL60(HB9), and HL60(HB9(del)) cells by qRT-PCR. Given are means and S.D. of three biological replicates. Values are normalized to β-actin; *, p ≤ 0.05.

Additionally, we validated the data derived from the expression Arrays for the four target genes by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3E). All four genes show a significant decreased gene expression in the HB9-positive sample compared with the HB9(del) and HB9(control) samples. PTGER2 gene expression in the HB9(del) sample is equal to the PTGER2 gene expression in the control sample. In that way, regulation of PTGER2 critically depends on the integrity of the entire homeodomain of HB9. The opposite effect is observed for the expression of ZYX, IL8, and ETS1. The repression was still detectable even though the homeodomain of HB9 was deleted (Fig. 3E).

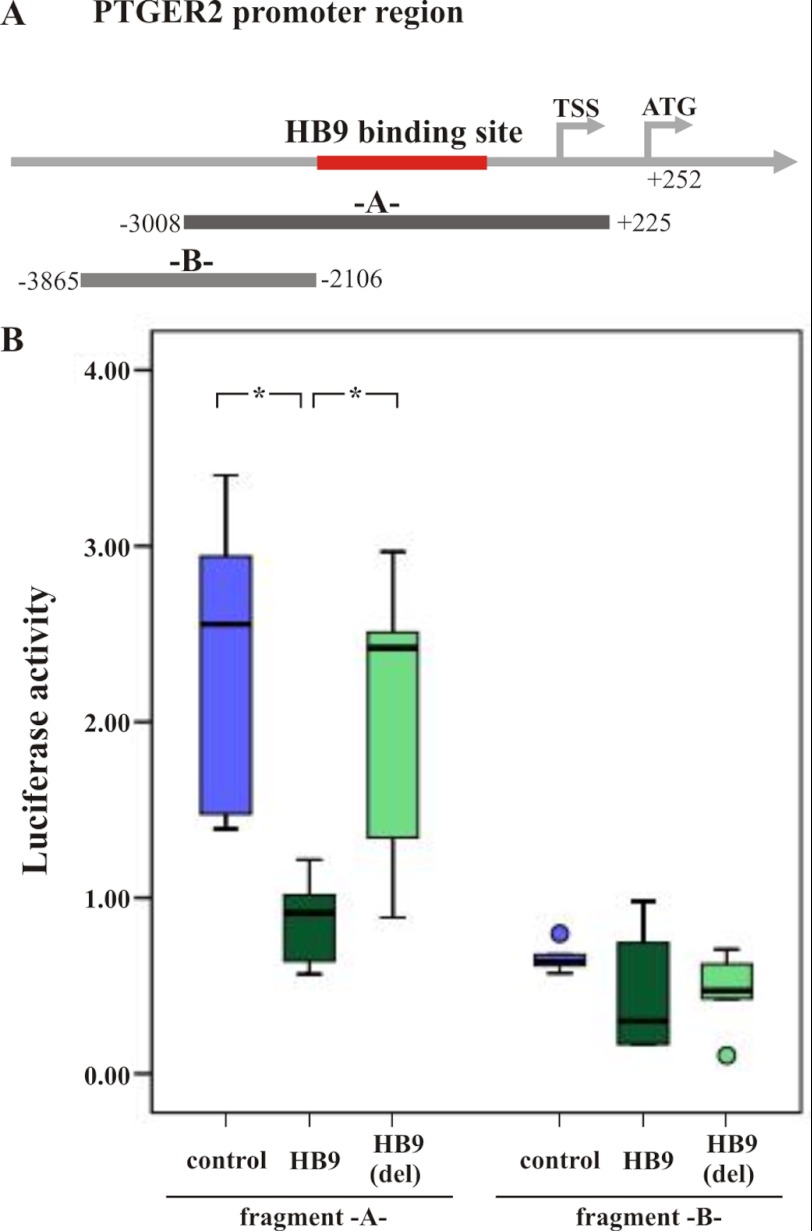

HB9 Binding Site within the PTGER2 Promoter Is Crucial for PTGER2 Gene Repression

Furthermore, we aimed to provide evidence that binding of HB9 to the PTGER2 promoter is essential for the down-regulation of gene expression and set up a luciferase reporter assay using the PTGER2 promoter sequence containing the putative HB9 binding site detected in the ChIP-on-chip experiments. We used the stably transfected HL60 cell lines with constitutive expression of either HB9, HB9(del), or the empty vector control that were used in the ChIP-on-chip analysis. Two different firefly luciferase reporter constructs were used for cotransfection. One contains the 3233-bp-long PTGER2 promoter region, including the HB9 binding site detected in the ChIP-on-chip analysis (pGL4.10-A-) and the other that serves as a potential negative control consists of a 1759-bp-long region upstream of the detected binding site (pGL4.10-B-) (Fig. 4A). In the stably transfected HL60 cells, we observed a cleavage of luciferin when HL60(mock) and HL60(HB9(del)) cells were co-transfected with the pGL4.10-A- vector. Luciferin cleavage was significantly reduced to background signaling with p values of 0.007 and 0.02, respectively, when HL60(HB9) cells were transfected with pGL4.10-A-. Additionally, luciferin cleavage was below background signal upon transfection of HL60(HB9), HL60(HB9del), and HL60(mock) cells with the control vector pGL4.10-B- (Fig. 4B). We additionally cloned a mutated pGL4.10-Amut-, which is identical to pGL4.10-A- and lacks the putative HB9 binding sequence (supplemental Fig. S4A). Both constructs show an equal activation of Luciferase activity in HL60(mock) cells (supplemental Fig. S4B). We next expressed both constructs in HL60(HB9) cells. pGL4.10-A- shows a significant higher repression of PTGER2 transcription compared with pGL4.10-Amut- (supplemental Fig. S4C).

FIGURE 4.

Luciferase assay in HL60 cells. A, illustration of the PTGER2 promoter regions used in the luciferase reporter assay. The firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL4.10-A- contains the HB9 binding site within the PTGER2 promoter region detected in the ChIP-on-chip experiments. The pGL4.10-B- vector serves as a negative control and contains a region upstream of the detected binding site. B, luciferase activity is indicated for the three stably transfected cell lines HL60(control), HL60(HB9), and HL60(HB9(del)) co-transfected with pGL4.10-A- or -B- and pGL4.73 using Amaxa Nucleofector. In HL60(HB9) cells, luciferase activity is significantly down-regulated compared with HL60(control) (p, 0.007) and HL60(HB9(del)) (p, 0.02) when reporter construct pGL4.10-A- was used. Co-transfection with reporter construct pGL4.10-B- did not reveal any regulation in luciferase activity. Shown are the mean and S.D. of n = 5 independent experiments, with three technical replicates in each experiment. TSS, transcription start site.

Thus, in HL60 cells, HB9 binding to the PTGER2 promoter results in its repression. This regulation is dependent on both the intact HB9 binding site within the PTGER2 promoter as well as the HB9 DNA binding motif.

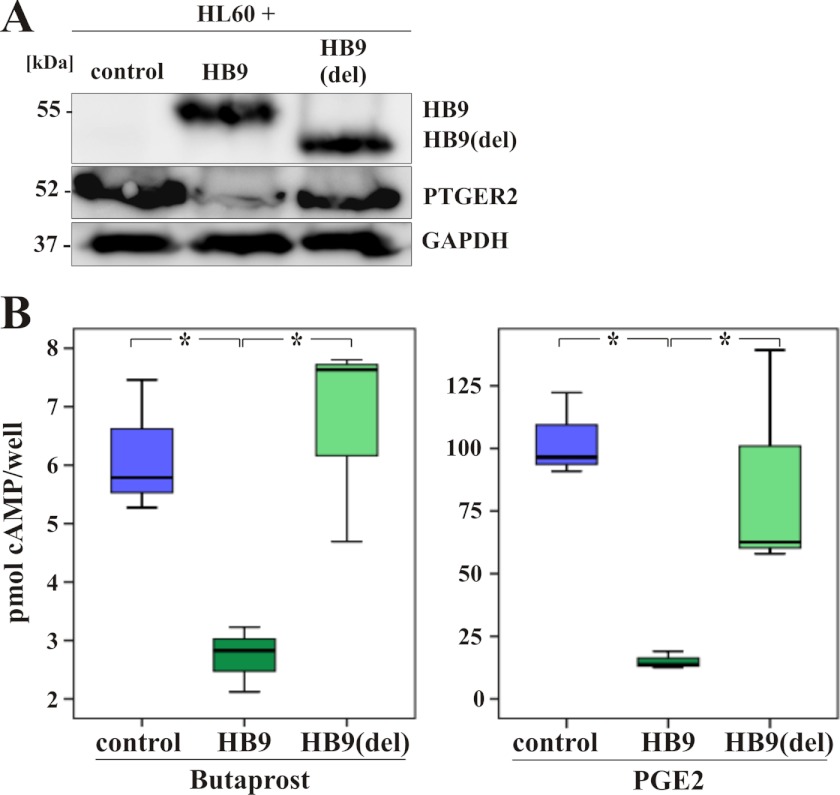

HL60(HB9) Cells Show Less Intracellular cAMP Mobilization

We next performed immunoblot analysis to verify that reduced PTGER2 mRNA expression concomitantly results in a reduced protein level. Indeed, HL60(HB9) cells clearly show a lower PTGER2 protein level compared with HL60(control) cells and HL60(HB9(del)) cells (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

HB9-positive HL60 cells show a reduced PTGER2 protein level and a lower intracellular cAMP content upon stimulation with PTGER2 agonists. A, immunoblot shows a reduced PTGER2 protein content in whole-cell lysates from HL60(HB9) cells compared with lysates from HL60(control) and HL60(HB9(del)) cells (middle lane). GAPDH serves as a loading control (lower lane). The integrity of FLAG-tagged HB9 and HB9(del) is shown in the upper lane, detected with an anti-FLAG antibody. B, HL60(control), HL60(HB9), and HL60(HB9(del)) cells were analyzed for their intracellular cAMP content after induction with 10 μm specific PTGER2 agonist butaprost or 5 μm PGE2 for 20 min, respectively. Values are normalized to the corresponding solvent control. *, p ≤ 0.05.

PTGER2 expression and stimulation with its agonists induces intracellular cAMP production. Hence, we measured the intracellular cAMP content in HL60(control), HL60(HB9), and HL60(HB9(del)) cells after stimulation with prostglandin 2 (PGE2) and butaprost, a PTGER2 specific agonist. Stimulation results in a significantly lower cAMP content in the HL60(HB9) cells compared with HL60(control) cells and HL60(HB9(del)) cells. In the same line, treatment of HL60(HB9) cells with PGE2 also results in significant lower cAMP levels compared with the control cells. Cell proliferation was not affected upon stimulation with PTGER2 agonists (Fig. 5B).

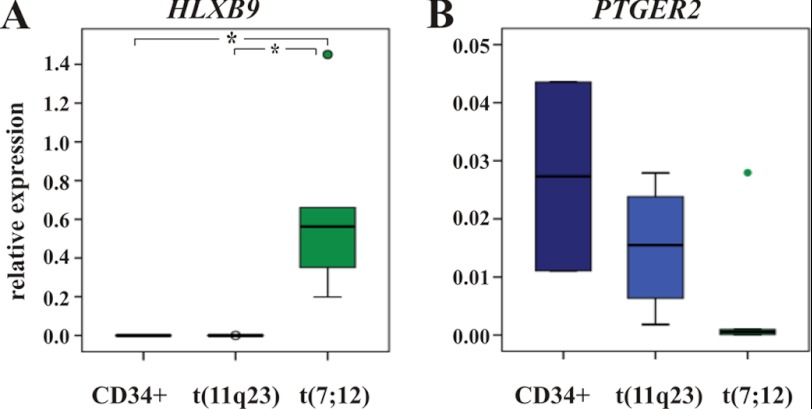

HB9 Regulates PTGER2 Expression in Translocation t(7;12) Positive Leukemic Cells

To verify the regulation of PTGER2 by HB9 in primary cells, we tested PTGER2 expression in hematopoietic blast cells from infants with translocation t(7;12) positive acute myeloid leukemia by qRT-PCR. Blast cells of 11q23/MLL positive leukemias and CD34+ cells of healthy individuals served as controls. We observed a 2.5-fold decrease in PTGER2 expression in translocation t(7;12) positive patients (n = 5) compared with the MLL/11q23 control samples (n = 5) and a 4.6-fold decreased expression compared with the CD34+ cells of healthy individuals (n = 2, Fig. 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

Differential expression of PTGER2 in primary cells. A and B, relative expression of HLXB9 and PTGER2 in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) samples measured by qRT-PCR. Compared is cDNA derived from patients with translocation t(7;12) (n = 5), translocation t(11q23)/MLL (n = 5) and CD34+ cells from healthy donors (n = 2). Values are normalized to β-actin; *, p ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study reports the first molecular analysis of HB9 target genes in hematopoietic cells. A gene ontology term analysis of 660 target genes, identified by ChIP-on-chip analysis in a myeloid cell line, reflects the involvement of HB9 in various malignancies. These are preferential malignant tissues which develop from tissues with physiologic HLXB9 expression such as neuronal cells or the gut. But most interestingly, acute myeloid leukemia appeared as a target, supporting the reliability of our cell line system used to decipher the functional role of HB9 in hematopoietic cells. A more detailed comparison of primary target genes obtained by ChIP-on-chip analysis together with 81 significantly regulated genes in a gene expression analysis revealed four target genes of HB9, namely PTGER2, IL8, ZYX, and ETS1, and all four genes have been linked to leukemic processes (24–26).

The regulation of PTGER2 on mRNA and protein level is specifically dependent on the intact HB9 homeodomain because HB9(del) lost its capacity to bind the PTGER2 promoter region and also failed to regulate PTGER2 gene and protein expression in HL60 cells as demonstrated in the ChIP-on-chip experiments. In agreement, reporter assays were performed using the same stably transfected cell lines that were used in the ChIP-on-chip studies. PTGER2 transcription is here clearly dependent on the intact HB9 DNA binding domain as well as on the putative HB9 binding motif within the PTGER2 promoter sequence.

PTGER2 is the receptor for the lipidic mediator prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). A coherent functional effect of an altered PTGER2 expression in leukemia is not described yet; however, on myeloid blast cells, only stimulation of PTGER2 has a functional effect compared with the expression of other PTGER receptors (28, 29).

Stimulation of PTGER2 activates cAMP production and subsequently induces gene regulation in a cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent manner (30). Respectively, we were able to show a reduced intracellular cAMP content upon stimulation of HL60(HB9) cells with PTGER2 agonists. Furthermore, suppression of PTGER expression is consistently valid in primary human samples of translocation t(7;12) positive leukemia.

Immunomodulatory effects of PGE2 on different cell types have already been specified (31, 32). The effect of PGE2 on hematopoietic cells is described in the physiologic modulation of the bone marrow homeostasis. Bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells, which participate in formation of the hematopoietic niche, represent a rich source of PGE2, which is critically involved in antiproliferative effects on various immune cells (33). Thus, it is imaginable that mesenchymal stromal cells may release PGE2 that provokes an immunomodulatory effect on translocation t(7;12) myeloid blast cells or their preleukemic precursors, respectively. Such a tumor-suppressive function of PTGER2 is suggested for neuroblastoma, where a decreased gene expression of PTGER2 is linked to the progression of cancer cells (34). Additionally, the stimulation of gastric cancer cells with PTGER2 agonists results in significant growth inhibition (35). A similar escape mechanism was described in non-malignant myeloid precursors of osteoclasts that try to escape PGE2-induced inhibition of bone resorption by down-regulation of their PTGER2 receptor (36).

A second interesting phenomenon is that PTGER2 expression modulates differentiation of osteoclasts. Hence, Kobayashi et al. (36, 37) demonstrated that PTGER2 is up-regulated in immature myeloid precursors and thus becomes down-regulated after the cells have differentiated into osteoclasts. Thus, further studies will show whether down-regulation of PTGER2 either provokes an escape mechanism from PGE2-derived immunomodulatory effects in the bone marrow niche or modulates differentiation of immature preleukemic cells.

In contrast to the regulation of PTGER2, HB9(del) failed to bind the promoter regions of the other three target genes IL8, ZYX, and ETS1 but still possess the ability of gene regulation. This suggests the existence of other yet unidentified DNA-binding motifs within full-length HB9, which are critical for the interaction of HB9 target genes. The limited number of four genes we identified from the overlap of data sets from ChIP-on-chip and gene expression analysis is a known phenomenon (38–40) and is based on the various conditions, which are important for a specific modulation of target gene regulation (41, 42). First, the gene expression is often controlled by cofactors recruited to the protein-DNA complexes as well as secondary or tertiary protein-protein interactions. Second, gene expression is often tissue-specific based on the expression of tissue related cofactors or specific signaling pathways.

To deeper analyze the effect of HLXB9 expression on the cellular gene expression pattern, independent of DNA binding, we conducted HLXB9 expressing HL60 cells to gene expression profiling and identified an overall repressive function of HB9. A subset of these differentially expressed genes can be attributed to the gene ontology term cell adhesion. Interestingly, previous comparative gene expression profiling of t(7;12) positive leukemias and CD34+ bone marrow cells from healthy children also revealed a high enrichment of the gene ontology term cell adhesion (supplemental Fig. S3). Consistency of the gene expression footprint in HLXB9 expressing HL60 cells and blast cells of translocation t(7;12) positive infants directs us to the conclusion that the gene expression signature in translocation t(7;12) positive blast cells is related to the concomitant high HLXB9 expression. The impact of HLXB9 on target gene expression, which is distributed to cell-cell or cell-matrix interactions, is fostered by a recently published study of Wilkens et al. (8). They identified the coordinated up-regulation of HLXB9 and genes involved in cell-cell interactions in hepatocellular carcinoma (8).

Thus, our study provides the first global molecular analysis of the expression network of HB9 in hematopoietic cells. In addition to the identification and characterization of primary and secondary target genes, we succeeded to identify PTGER2 as a target gene of HB9 in hematopoietic cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the Biologisch Medizinisches Forschungszentrum of the Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf for conducting hybridization of Affymetrix arrays. We thank Prof. Jochen Harbott, Dr. Silja Röttgers, Dr. Jutta Bradtke, and Dr. Andrea Teigler-Schlegel (Molecular Cytogenetic Laboratory, Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany) for providing primary patient material. We thank Prof. Dr. Fritz Boege and Dr. Beatrice Bornholz (Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Diagnostics, University of Düsseldorf) for support regarding the cAMP assays and Silke Furlan for excellent technical support.

This work was partially funded by the Forschungskommission of the Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harrison K. A., Druey K. M., Deguchi Y., Tuscano J. M., Kehrl J. H. (1994) A novel human homeobox gene distantly related to proboscipedia is expressed in lymphoid and pancreatic tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19968–19975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gehring W. J., Qian Y. Q., Billeter M., Furukubo-Tokunaga K., Schier A. F., Resendez-Perez D., Affolter M., Otting G., Wüthrich K. (1994) Homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell 78, 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harrison K. A., Thaler J., Pfaff S. L., Gu H., Kehrl J. H. (1999) Pancreas dorsal lobe agenesis and abnormal islets of Langerhans in Hlxb9-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 23, 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martín M., Gallego-Llamas J., Ribes V., Kedinger M., Niederreither K., Chambon P., Dollé P., Gradwohl G. (2005) Dorsal pancreas agenesis in retinoic acid-deficient Raldh2 mutant mice. Dev. Biol. 284, 399–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thaler J., Harrison K., Sharma K., Lettieri K., Kehrl J., Pfaff S. L. (1999) Active suppression of interneuron programs within developing motor neurons revealed by analysis of homeodomain factor HB9. Neuron 23, 675–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Currarino G., Coln D., Votteler T. (1981) Triad of anorectal, sacral, and presacral anomalies. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 137, 395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hollington P., Neufing P., Kalionis B., Waring P., Bentel J., Wattchow D., Tilley W. D. (2004) Expression and localization of homeodomain proteins DLX4, HB9, and HB24 in malignant and benign human colorectal tissues. Anticancer Res. 24, 955–962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilkens L., Jaggi R., Hammer C., Inderbitzin D., Giger O., von Neuhoff N. (2011) The homeobox gene HLXB9 is upregulated in a morphological subset of poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 458, 697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deguchi Y., Kehrl J. H. (1991) Selective expression of two homeobox genes in CD34-positive cells from human bone marrow. Blood 78, 323–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. von Bergh A. R., van Drunen E., van Wering E. R., van Zutven L. J., Hainmann I., Lönnerholm G., Meijerink J. P., Pieters R., Beverloo H. B. (2006) High incidence of t(7;12)(q36;p13) in infant AML but not in infant ALL, with a dismal outcome and ectopic expression of HLXB9. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 45, 731–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simmons H. M., Oseth L., Nguyen P., O'Leary M., Conklin K. F., Hirsch B. (2002) Cytogenetic and molecular heterogeneity of 7q36/12p13 rearrangements in childhood AML. Leukemia 16, 2408–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slater R. M., von Drunen E., Kroes W. G., Weghuis D. O., van den Berg E., Smit E. M., van der Does-van den Berg A., van Wering E., Hählen K., Carroll A. J., Raimondi S. C., Beverloo H. B. (2001) t(7;12)(q36;p13) and t(7;12)(q32;p13)–translocations involving ETV6 in children 18 months of age or younger with myeloid disorders. Leukemia 15, 915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tosi S., Harbott J., Teigler-Schlegel A., Haas O. A., Pirc-Danoewinata H., Harrison C. J., Biondi A., Cazzaniga G., Kempski H., Scherer S. W., Kearney L. (2000) t(7;12)(q36;p13), a new recurrent translocation involving ETV6 in infant leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 29, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beverloo H. B., Panagopoulos I., Isaksson M., van Wering E., van Drunen E., de Klein A., Johansson B., Slater R. (2001) Fusion of the homeobox gene HLXB9 and the ETV6 gene in infant acute myeloid leukemias with the t(7;12)(q36;p13). Cancer Res. 61, 5374–5377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hauer J., Tosi S., Schuster F. R., Harbott J., Kolb H. J., Borkhardt A. (2008) Graft versus leukemia effect after haploidentical HSCT in a MLL-negative infant AML with HLXB9/ETV6 rearrangement. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 50, 921–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tosi S., Hughes J., Scherer S. W., Nakabayashi K., Harbott J., Haas O. A., Cazzaniga G., Biondi A., Kempski H., Kearney L. (2003) Heterogeneity of the 7q36 breakpoints in the t(7;12) involving ETV6 in infant leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 38, 191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wildenhain S., Ruckert C., Röttgers S., Harbott J., Ludwig W. D., Schuster F. R., Beldjord K., Binder V., Slany R., Hauer J., Borkhardt A. (2010) Expression of cell-cell interacting genes distinguishes HLXB9/TEL from MLL-positive childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 24, 1657–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mielke C., Tümmler M., Schübeler D., von Hoegen I., Hauser H. (2000) Stabilized, long-term expression of heterodimeric proteins from tricistronic mRNA. Gene 254, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paquette J., Tokuyasu T. (2010) EGAN: exploratory gene association networks. Bioinformatics 26, 285–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Irizarry R. A., Hobbs B., Collin F., Beazer-Barclay Y. D., Antonellis K. J., Scherf U., Speed T. P. (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smyth G. K. (2004) Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3, Article3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nagel S., Kaufmann M., Scherr M., Drexler H. G., MacLeod R. A. (2005) Activation of HLXB9 by juxtaposition with MYB via formation of t(6;7)(q23;q36) in an AML-M4 cell line (GDM-1). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 42, 170–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dalton W. T., Jr., Ahearn M. J., McCredie K. B., Freireich E. J., Stass S. A., Trujillo J. M. (1988) HL-60 cell line was derived from a patient with FAB-M2 and not FAB-M3. Blood 71, 242–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collyn d'Hooghe M., Galiègue-Zouitina S., Szymiczek D., Lantoine D., Quief S., Loucheux-Lefebvre M. H., Kerckaert J. P. (1993) Quantitative and qualitative variation of ETS-1 transcripts in hematologic malignancies. Leukemia 7, 1777–1785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y., Tetko I. V., Hall M. A., Frank E., Facius A., Mayer K. F., Mewes H. W. (2005) Gene selection from microarray data for cancer classification–a machine learning approach. Comput. Biol. Chem. 29, 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kornblau S. M., McCue D., Singh N., Chen W., Estrov Z., Coombes K. R. (2010) Recurrent expression signatures of cytokines and chemokines are present and are independently prognostic in acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplasia. Blood 116, 4251–4261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deleted in proof

- 28. Denizot Y., Donnard M., Truffinet V., Malissein E., Faucher J. L., Turlure P., Bordessoule D., Trimoreau F. (2005) Functional EP2 receptors on blast cells of patients with acute leukemia. Int. J. Cancer 115, 499–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malissein E., Reynaud S., Bordessoule D., Faucher J. L., Turlure P., Trimoreau F., Denizot Y. (2006) PGE(2) receptor subtype functionality on immature forms of human leukemic blasts. Leuk. Res. 30, 1309–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Regan J. W. (2003) EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptor signaling. Life Sci. 74, 143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fedyk E. R., Ripper J. M., Brown D. M., Phipps R. P. (1996) A molecular analysis of PGE receptor (EP) expression on normal and transformed B lymphocytes: coexpression of EP1, EP2, EP3β, and EP4. Mol. Immunol. 33, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santoro M. G., Philpott G. W., Jaffe B. M. (1977) Inhibition of B-16 melanoma growth in vivo by a synthetic analog of prostaglandin E2. Cancer Res. 37, 3774–3779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yagi H., Soto-Gutierrez A., Parekkadan B., Kitagawa Y., Tompkins R. G., Kobayashi N., Yarmush M. L. (2010) Mesenchymal stem cells: Mechanisms of immunomodulation and homing. Cell Transplant. 19, 667–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sugino Y., Misawa A., Inoue J., Kitagawa M., Hosoi H., Sugimoto T., Imoto I., Inazawa J. (2007) Epigenetic silencing of prostaglandin E receptor 2 (PTGER2) is associated with progression of neuroblastomas. Oncogene 26, 7401–7413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okuyama T., Ishihara S., Sato H., Rumi M. A., Kawashima K., Miyaoka Y., Suetsugu H., Kazumori H., Cava C. F., Kadowaki Y., Fukuda R., Kinoshita Y. (2002) Activation of prostaglandin E2-receptor EP2 and EP4 pathways induces growth inhibition in human gastric carcinoma cell lines. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 140, 92–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kobayashi Y., Take I., Yamashita T., Mizoguchi T., Ninomiya T., Hattori T., Kurihara S., Ozawa H., Udagawa N., Takahashi N. (2005) Prostaglandin E2 receptors EP2 and EP4 are down-regulated during differentiation of mouse osteoclasts from their precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24035–24042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kobayashi Y., Mizoguchi T., Take I., Kurihara S., Udagawa N., Takahashi N. (2005) Prostaglandin E2 enhances osteoclastic differentiation of precursor cells through protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of TAK1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11395–11403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scacheri P. C., Davis S., Odom D. T., Crawford G. E., Perkins S., Halawi M. J., Agarwal S. K., Marx S. J., Spiegel A. M., Meltzer P. S., Collins F. S. (2006) Genome-wide analysis of menin binding provides insights into MEN1 tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet. 2, e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hammerich-Hille S., Kaipparettu B. A., Tsimelzon A., Creighton C. J., Jiang S., Polo J. M., Melnick A., Meyer R., Oesterreich S. (2010) SAFB1 mediates repression of immune regulators and apoptotic genes in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3608–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nakachi Y., Yagi K., Nikaido I., Bono H., Tonouchi M., Schönbach C., Okazaki Y. (2008) Identification of novel PPARγ target genes by integrated analysis of ChIP-on-chip and microarray expression data during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 372, 362–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Georges A. B., Benayoun B. A., Caburet S., Veitia R. A. (2010) Generic binding sites, generic DNA-binding domains: where does specific promoter recognition come from? FASEB J. 24, 346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zappavigna V., Sartori D., Mavilio F. (1994) Specificity of HOX protein function depends on DNA-protein and protein-protein interactions, both mediated by the homeo domain. Genes Dev. 8, 732–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.