Abstract

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) HIV-1 presents a challenge to the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy (ART). To examine mechanisms leading to MDR variants in infected individuals, we studied recombination between single viral genomes from the genital tract and plasma of a woman initiating ART. We determined HIV-1 RNA sequences and drug resistance profiles of 159 unique viral variants obtained before ART and semiannually for 4 years thereafter. Soon after initiating zidovudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine, resistant variants and intrapatient HIV-1 recombinants were detected in both compartments; the recombinants had inherited genetic material from both genital and plasma-derived viruses. Twenty-three unique recombinants were documented during 4 years of therapy, comprising ∼22% of variants. Most recombinant genomes displayed similar breakpoints and clustered phylogenetically, suggesting evolution from common ancestors. Longitudinal analysis demonstrated that MDR recombinants were common and persistent, demonstrating that recombination, in addition to point mutation, can contribute to the evolution of MDR HIV-1 in viremic individuals.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) HIV-1 has emerged globally as a challenge to the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART).1,2 In infected individuals, the HIV-1 population exists as a dynamic mixture of genomic variants evolving through mutation, recombination, and selection, all of which contribute to the emergence of MDR viruses.3,4 Not only does HIV-1's error-prone reverse transcriptase (RT) introduce myriad point mutations daily, but viral recombination encompasses large portions of the viral genome and may thereby lead to the simultaneous acquisition of numerous genetic traits conferring selective advantages to the new HIV-1 strain.3–5

HIV-1 recombination in vitro is frequent and can result in MDR viruses.5–7 Recombinants comprising multiple viral subtypes have been isolated in infected individuals as well,8,9 and intrapatient recombination has been documented in detail.8–11 It has therefore been hypothesized that recombination accelerates the development of MDR HIV-1 in patients.3,5–7 One report described a panresistant HIV-1 strain that developed after probable superinfection followed by recombination12; in that unusual and illustrative case, both the putative donor and recipient of the superinfecting virus were chronically infected and extensively treated. MDR HIV-1 occurs commonly, however, without evidence of superinfection. The evolution and fate of MDR HIV-1 recombinants in a previously untreated individual have not yet been described in detail, prompting this study.

Demonstrating intrapatient recombination in infected individuals can be challenging because most HIV-1 variants within a single person are too similar to permit detection of chimeric strains. Previously, we identified intrapatient recombinants by analyzing viruses from the female genital tract and plasma, compartments displaying HIV-1 variants that are phylogenetically related yet distinct.10 This report extends these studies to examine the role of recombination in the evolution of MDR HIV-1.

We performed a retrospective analysis of HIV resistance in samples obtained from the plasma and genital tract of a subject participating in the Bronx, NY site of the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a multicenter, natural history investigation of HIV-1 infection of women. WIHS participation entails a semiannual interview, examination, and collection of blood and cervicovaginal lavage fluid (CVL).10,11 A detailed history of ART was obtained and medical records reviewed. As an observational cohort study, the WIHS does not provide direct treatment of participants, who receive their care in the community. The institutional review boards at Montefiore Hospital and the New York State Department of Health approved the study and the subject provided informed consent.

CVL fluid was collected, cryopreserved, and tested for semen as described10; it was also visually inspected for blood, with no evidence of either semen or blood found. HIV-1 RNA in each compartment was quantified using NucliSens (bioMérieux, Durham, NC).

Virion-derived RNA was extracted and cDNA synthesized as described.10 Plasma and CVL were processed separately to avoid cross-contamination and PCR-mediated recombination.10,13 A 1.6-kb DNA fragment encompassing the HIV-1 protease-RT region was sequenced from both individual variants and predominant populations,11 resulting in 173 unique sequences (159 individual variants and 14 population-based sequences).

The phylogenetic tree comprising all 159 individual variants was constructed using maximum likelihood including the HKY and gamma model of nucleotide substitution.

Recombinants and their breakpoints were identified by the Bayesian dual change point (BDCP) model14,15 and confirmed using SimPlot and GARD.16,17 The BDCP framework allows for varying evolutionary rates, selective pressures, and trees along the alignment while simultaneously providing estimates of uncertainty for those quantities including the location and number of recombination events. Initial screening for putative recombinants began by constructing a tree of all single-variant sequences using the maximum likelihood method (DNAML). In this tree, the branches connecting to the suspected recombinants were rooted much more deeply than expected.

We considered as likely parental sequences the variants clustering nearest to the suspected recombinants that were temporally consistent. In this approach, the restricted data set for each recombinant consists of N=5 aligned sequences, where one sequence is a suspected recombinant, three sequences are potential parental sequences, and one, an outgroup sequence. By testing all possible parental pairs using the BDCP model, we found that our original set of five sequences for each recombinant had the highest posterior probability of recombination. To ensure against phenotypic attraction, we deleted all resistance-associated mutations from the alignment; we also repeated all analyses after deleting all of the nonsynonomous sites. Putative parental sequences employed in all computational analyses were those obtained at the first time point after initiation of ART, February 2000.

A zero-inflated Poisson model was used to compare the number of mutations conferring high-level drug resistance in recombinant vs. nonrecombinant strains and to test if the proportion of recombinant variants changed over time.

Genotypic drug resistance was determined using the Stanford HIV drug-resistance website (http://hivdb.stanford.edu). Phenotypic resistance was determined for the sequences obtained in 1998 and 2000 by InPheno AG using the PhenoTecT method.18

Replicative capacity (RC) was performed by InPheno using the cellular system deCIPhR, which quantitatively translates the replication of a recombinant virus into a colorimetric readout. As the system permits three to four cycles of viral replication, the calculation of RC is based upon multiple rounds of viral replication rather than a single cycle. To determine RC, the patient's HIV-1 RT gene was cloned into a vector, forming a recombinant virus, and the RC of the recombinant was compared to that of a reference strain. To evaluate the relative RC of an HIV-1 recombinant carrying a patient-derived RT gene in an isogenic pNL4-3 background, maximal readout of a reference strain (pNL4-3) was measured in the deCIPheR format in the absence of inhibitor (maxref) and the minimal readout was also assessed after incubation with a dose of a protease inhibitor ensuring complete suppression of viral replication (minref). The same calculations were made for the recombinant virus carrying the RT gene from a patient (maxpat and minpat). A value for RC in the context of a replicating virus was then calculated as the ratio: RCpat(%)=(maxpat−minpat)/maxref−minref )×100.

The study patient, a 40-year-old African-American woman with chronic, asymptomatic HIV-1 infection, initiated ART comprising zidovudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine in early 2000. We analyzed HIV-1 from her plasma and genital tract in May 1998, prior to therapy; February 2000, shortly after ART began; and semiannually for 4 years thereafter. She reported continuing the same ART regimen for seven of the nine visits during this period, with drug holidays at two visits (Table 1). The patient remained asymptomatic during the entire study period, without evidence of HIV-related illnesses or sexually transmitted diseases. She did, however, report crack cocaine use at every WIHS visit as well as intermittent adherence to ART related to her drug use. Urine toxicology confirmed crack use in February 2000.

Table 1.

Clinical, Immunologic, and Virologic Characteristics

|

Patient characteristics |

Virologic analyses of variants |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | ART | CD4 cell count, cells/mm3 | Site of origina | HIV-1 RNA load, log copies/ml | Total variants, N | Recombinants, N, (%) |

| 5-98 | None | 120 | Plasma | 5.34 | NA | NA |

| 2-00 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 359 | Plasma | 4.30 | 22 | Parental strainsb |

| CVL | 4.85 | 33 | Parental strainsb | |||

| 7-00 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 387 | Plasma | 4.30 | 17 | 1(6) |

| CVL | 4.15 | 17 | 5 (29) | |||

| 2-01 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 368 | Plasma | 3.68 | 9 | 2(22) |

| 7-01 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 358 | Plasma | 3.99 | 7 | 4 (57) |

| 2-02 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 530 | Plasma | 3.76 | 10 | 2 (20) |

| 7-02 | None | 224 | Plasma | 4.77 | 10 | 3 (30) |

| 1-03 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 338 | Plasma | 4.18 | 9 | 3 (33) |

| 6-03 | None | 211 | Plasma | 5.80 | 11 | 1 (9) |

| 12-03 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | 249 | Plasma | 3.20 | 14 | 2 (14) |

| Total | 159 | 23 (22)c | ||||

Sequences were obtained from plasma at each time point and from CVL obtained in February and July of 2000. At later time points, CVL viral loads were <80 copies/ml. Data in the three columns furthest to the right refer to analyses of samples from either CVL or plasma.

ART was initiated shortly before the 2-00 visit and resistance mutations were detected for the first time in samples from that visit. We therefore considered variants from that time point as putative parental strains in the recombination analyses.

Because strains obtained in 2-00 were considered as putative parental strains, the 104 variants obtained after 2-00 were included to calculate the percentage of recombinant variants.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; AZT, zidovudine; 3TC, lamivudine; NVP, nevirapine; CVL, cervicovaginal lavage; NA, not analyzed because the consensus sequence was obtained only for this time point.

In May 1998, prior to ART, the patient displayed a high plasma viral load and CD4+ cell depletion (HIV-1 RNA load,150,000 copies/ml; CD4 count, 120 cells/mm3) (Table 1). Seven months after initiating ART, her CD4 count had risen to 387 cells/mm3 and her HIV-1 RNA load was reduced by one log. Although HIV-1 in the CVL was suppressed by February 2001, after ∼14 months on HAART, plasma viremia persisted throughout the study period, suggesting the possibility of drug resistance (Table 1). Subsequent to the WIHS visits reported here, the subject stopped ART, frequently missed study visits, and could not be reached for follow-up. She was reported to have died in 2007 after being struck by a truck. As an observational cohort study, the WIHS does not provide direct treatment of participants, who receive their care in the community, and additional clinical information could not be obtained.

To study the evolution of HIV-1 drug resistance in this individual with persistent viremia despite ART, we analyzed serial HIV-1 sequences from the plasma and genital tract; 173 unique HIV-1 sequences (159 individual and 14 consensus sequences) encompassing the protease and RT genes were determined (GenBank accession nos. DQ133606–DQ133701 and FJ822891–FJ822960). Computational analyses including a BLAST search showed no evidence of contamination, and open reading frames were intact, without significant deletions, insertions, alterations, or nonsense mutations. All sequences were subtype B.

Before treatment, in May 1998, there was no evidence of drug resistance in either compartment. By February 2000, however, soon after initiation of ART, the majority of variants in both sites displayed phenotypic and genotypic resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI). The pattern of resistance mutations, however, differed between the two sites (Fig. 1). The most common mutation in plasma, observed in the consensus sequence and 14 of 22 variants (63%), was K103N; the most common in CVL, by contrast, was G190S. Of the 33 CVL variants, 20 (61%) exhibited G190S, and 15 of these also exhibited A98V, a mutation that was detected solely in the genital compartment. A minority of CVL variants (33%) bore K103N.

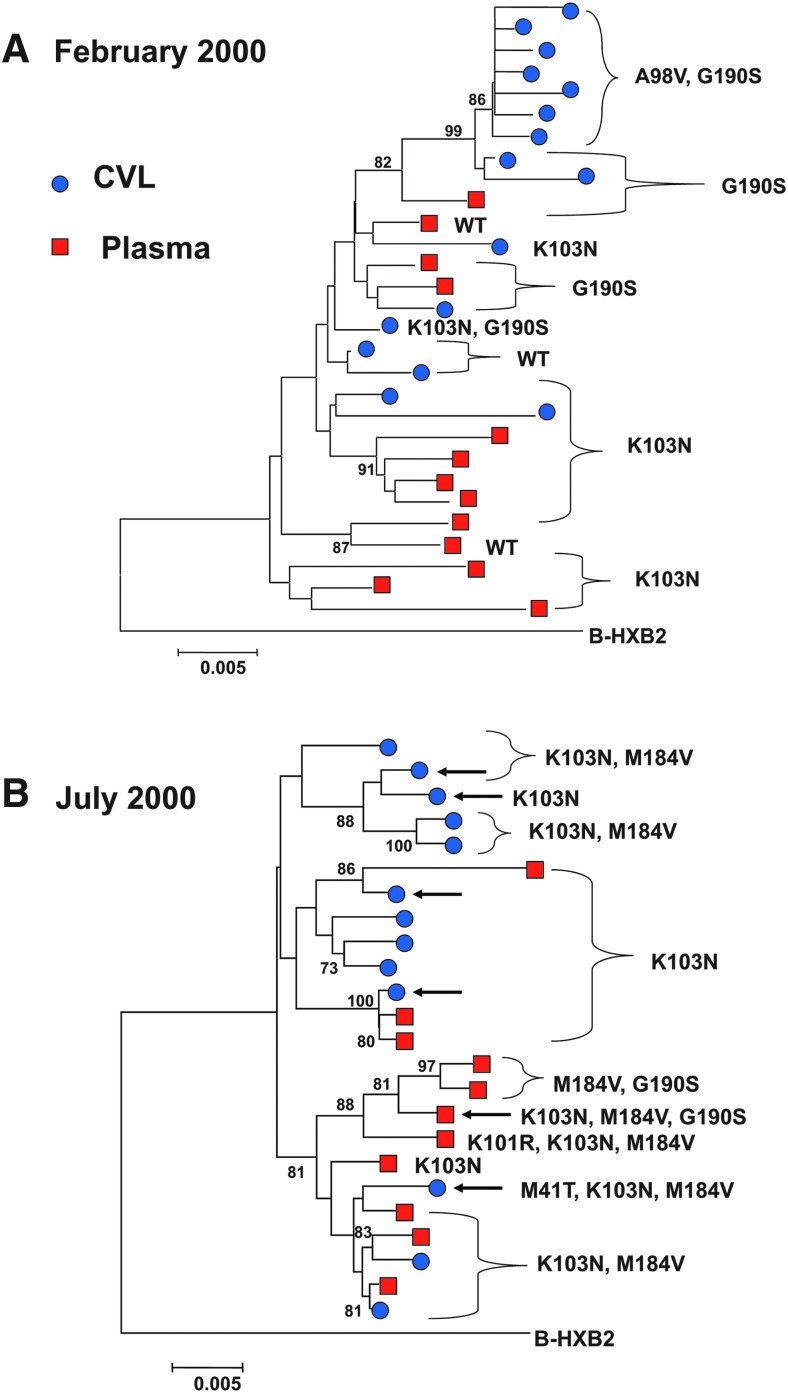

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic trees of the HIV-1 pol genes obtained from the plasma and genital tract of the study patient in February and July 2000. Each tree depicts the phylogenetic relationship and major drug resistance mutations of unique sequences of a ∼1600-bp region encompassing the HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase (RT) genes derived from the plasma and genital tract of the study patient and the subtype B reference strain HXB2. Numbers at branch points represent bootstrap values. ●, genital tract variants; ▪, plasma variants. WT=wild type. (A) Variants obtained in February 2000. (B) Variants obtained in July 2000. Arrows indicate recombinant strains. Phylogenetic trees depicted here were constructed of 29 representative sequences from this patient obtained in February (A) and 24 obtained in July (B). Trees depicting all 89 sequences are available upon request.

A phylogenetic tree constructed of CVL and plasma sequences obtained in February 2000 demonstrated partial compartmentalization, with CVL variants bearing the linked A98V-G190S mutations clustering as a distinct branch of the tree and plasma sequences bearing K103N clustering on three different branches (Fig. 1A).

Five months later, the K103N and M184V resistance mutations predominated in both compartments, conferring genotypic and phenotypic resistance to NNRTIs and lamivudine (Fig. 1B). The A98V mutation was no longer detected. These findings raised the possibility that strains observed in July 2000 may have arisen in part through viral recombination.

Computational analyses of variants obtained in July 2000 identified six intrapatient recombinants comprising sequences from CVL and plasma (indicated by arrows in Fig. 1B); each showed evidence of having evolved through recombination from strains present 5 months earlier. To detect recombination, we used SimPlot, Bayesian dual change-point (BDCP) analysis, and GARD. Each recombinant identified here was recognized as such by all three methods, with agreement regarding their genetic breakpoints.

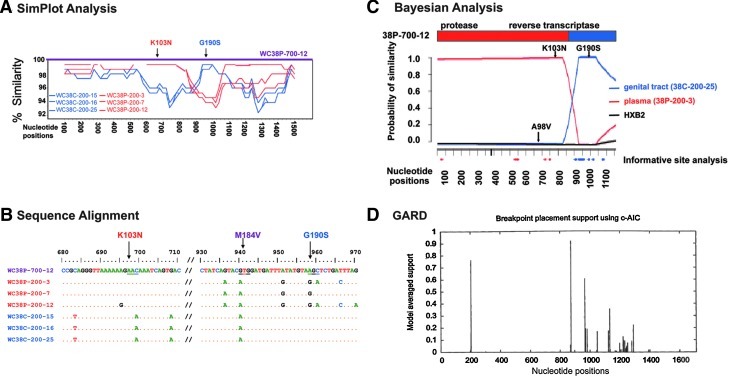

Recombinant WC38-P-700-12, detected in plasma, displayed three resistance mutations (K103N, M184V, G190S) (Fig. 1B), with analyses demonstrating that the K103N mutation was derived from a plasma strain and the G190S from CVL (Fig. 2A–C). The Bayesian model identified the most likely plasma parental strain as contributing the K103N mutation and the likely CVL parental strain as contributing G190S (posterior probability > 0.99, Fig. 2C). All methods delineated a breakpoint close to nucleotide 880 of the pol gene (Fig. 2A, C, and D). Computational analyses indicated that all six unique recombinants obtained in July 2000 were likely to have been derived from a plasma strain bearing K103N and a CVL variant bearing both A98V and G190S mutations; these recombinants displayed a range of mutations (Table 2). To ensure that the results were not biased by phenotypic attraction, the analyses were repeated after deleting all of the resistance mutations, and the conclusions remained unchanged.

FIG. 2.

Computational analysis of the recombinant HIV-1 genome WC38P-700-12. Viral variants are identified as follows: WC38 denotes Wadsworth Center Subject 38; P or C denotes plasma or CVL as the compartment of origin; numbers that follow denote the month and year the variant was obtained (700 denotes July of 2000); the final number identifies the variant obtained from each compartment on each date. (A) SimPlot compared the similarity of the query sequence, putative recombinant WC38P-700-12, to three representative sequences from the subject's plasma and three from CVL; these representative sequences were obtained in February 2000 and served as most likely parental strains. A graph depicts the degree of similarity of each likely parental strain to the query sequence, with plasma sequences in red and CVL sequences in blue. The SimPlot demonstrates that the portion of the putative recombinant genome WC38P-700-12 encoding the K103N mutation displays ∼99% similarity to the plasma-derived reference sequences; the portion encoding G190S, by contrast, displays an equally strong resemblance to the CVL strains. There is a breakpoint at approximately nucleotide 880 of the RT-protease region. (B) Alignment of the sequence of putative recombinant WC38P-700-12, displayed as the uppermost sequence, with the same three plasma and three CVL-derived most likely sequences displayed in (A). Plasma sequences are depicted in red and CVL sequences in blue. Nucleotides differing from WC38P-700-12 are shown; if identical to that strain, they are depicted as dots. This alignment demonstrates that the sequence of the putative recombinant WC38P-700-12 matches the plasma-derived sequences in the region encoding the K103N mutation and the CVL-derived sequences in the region encoding G190S. Neither plasma nor CVL-derived sequences obtained in February 2000 displayed the M184V mutation seen in July 2000, consistent with the evolution of this mutation between the two time points. (C) Bayesian dual changepoint (BDCP) analysis comparing putative recombinant HIV-1 variant WC38P-700-12 to three other HIV-1 strains: the putative recombinant is compared to two likely parental viral variants derived from the same subject 5 months earlier and the reference strain HXB2. The abscissa represents the alignment of nucleotides of the HIV-1 protease and RT genes; the ordinate displays the probability of similarity between the recombinant strains and the likely parental and reference sequences. The bar diagram at the top represents the protease and RT genes of the recombinant strain, with the breakpoint indicated at approximately nucleotide 880 by a change in color. Sequences from the genital tract (CVL) are shown in blue, those from the plasma are red, and the reference strain HXB2 is black. Resistance mutations displayed by putative parental variants are indicated by arrows. The plasma-derived recombinant variant WC38P-700-12 was compared here to CVL strain WC38C-200-25, plasma strain WC38P-200-3, and HXB2 (posterior probability > 0.99). This figure illustrates that the K103N mutation was contributed by the likely plasma parental strain WC38-200-3 and the G190S mutation by the likely CVL parental strain WC38-C-200-25. Informative site analysis, indicated by red and blue dots along the abscissa, are concordant with the findings of the BDCP analysis. (D) GARD confirms that there is a >90% probability of a recombination breakpoint at approximately the 880 nucleotide position of variant WCP-700-12.

Table 2.

Drug Resistance Profile of Recombinants

| Date | Site of origina | Variants, Nb | Resistance mutations | Drug resistance interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-00 | Plasma | 1 | K103N, M184V, G190S | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R |

| CVL | 3 | K103N | NNRTI-R | |

| CVL | 1 | K103N, M184V | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R | |

| CVL | 1 | M41T, K103N, M184V | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R | |

| 2-01 | Plasma | 1 | K103N, M184V, G190S | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R |

| Plasma | 1 | M184V, G190S | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R | |

| 7-01 | Plasma | 1 | M41L, M184V, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R, 3TC-R |

| Plasma | 1 | M184V, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R, 3TC-R | |

| Plasma | 2 | M184V, G190S | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R | |

| 2-02 | Plasma | 2 | M41L, M184V, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R, 3TC-R |

| 7-02 | Plasma | 2 | M184V, G190S, T215S | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R |

| Plasma | 1 | K101E, G190S | NNRTI-R | |

| 1-03 | Plasma | 1 | M41L, K101E, M184V, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R, 3TC-R |

| Plasma | 1 | M41L, M184V, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R, 3TC-R | |

| Plasma | 1 | K101E, M184V, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R, 3TC-R | |

| 6-03 | Plasma | 1 | K103N | NNRTI-R |

| 12-03 | Plasma | 1 | M41L, K103N, G190S, T215F | NNRTI-R, AZT-R |

| Plasma | 1 | M41L | None |

Sequences were obtained from both plasma and CVL samples at the February and July 2000 visits. For later visits, viral loads were <80 copies/ml in the CVL, precluding sequence analysis.

An average of 12 (range 7–17) variants were analyzed from each time point from July 2000 to December 2003 for the presence of recombination. Only the recombinant variants are characterized in the table.

NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; 3TC, lamivudine; AZT, zidovudine; R, high level resistance.

M184V was first detected in this patient in July 2000, when it appeared in the majority of strains including three recombinants. Because M184V appears to have emerged as a prevalent mutation in Patient 38 between visits, we could not ascertain the role of recombination in its emergence or spread in the viral population.

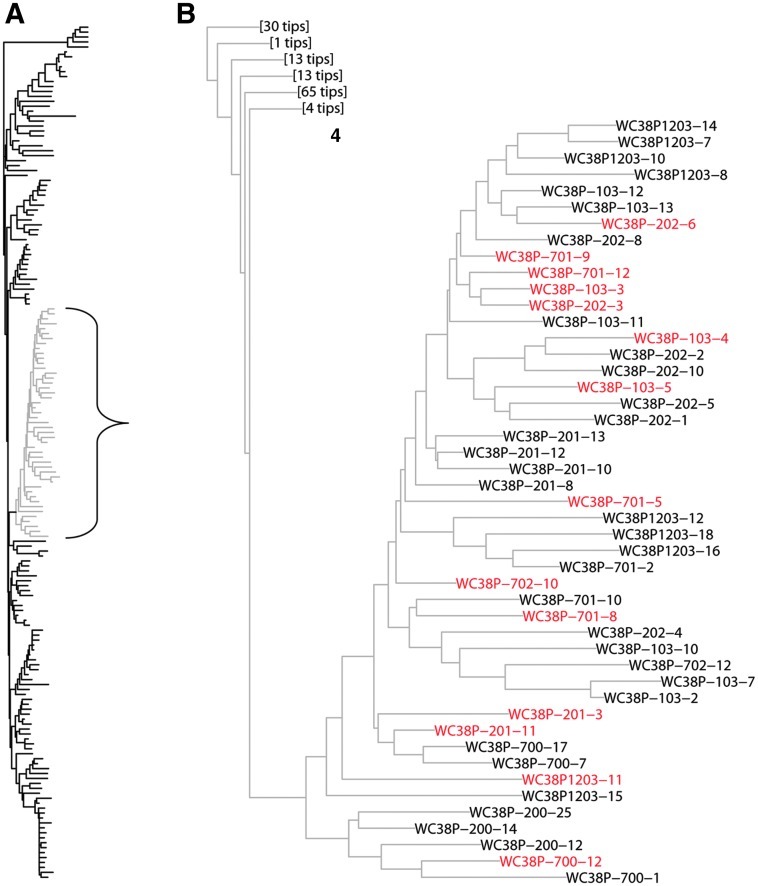

MDR recombinants persisted in this patient, with serial analyses documenting 23 recombinants detected during 4 years of ART (Table 1, Fig. 3). Recombinants persisted at a mean level of ∼22% of HIV-1 variants, without significant variation in the proportion of recombinants over time (p>0.1). Most recombinants displayed similar breakpoints and clustered phylogenetically. Figure 3, depicting a phylogenetic analysis of all 159 individual variants, demonstrates that the majority of recombinants cluster on one branch of the evolutionary tree. Recombinants detected throughout the 4-year period grouped closely. These findings suggest that the recombinants evolved from common ancestors in this patient.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of all individual HIV-1 pol sequences obtained from the genital tract and plasma of Patient 38. (A) Phylogenetic tree composed of all 159 individual sequences of the RT-protease region obtained from Patient 38. Fourteen of the 23 recombinants (61%) appeared on one branch of the tree, which is depicted in gray and enclosed by a bracket. (B) Enlargement of the branch bracketed in (A). Recombinants appear in red. "Tips" refers to the number of terminal branches in the portion of the tree displayed in full in (A).

Because HIV-1 was suppressed in the CVL by February 2001, most recombinants detected in this study were obtained from plasma (Table 1). All plasma-derived recombinants contained genetic material originating in the CVL and 14 of 18 plasma recombinants displayed a G190S mutation contributed by a CVL strain, underscoring the contribution of CVL-derived sequences to variants in the plasma compartment. Drug resistance profiles of the recombinants showed that most displayed multidrug resistance, with up to five resistance mutations detected in each variant (Table 2). In the first year after starting ART, most recombinants demonstrated genotypic resistance to NNRTIs and lamivudine, and later, the majority showed resistance to the three antiretroviral agents the patient was taking: zidovudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine. Although the number of drug resistance mutations increased over time in both recombinant and nonrecombinant strains, a comparison of these numbers in both groups of variants showed a trend toward greater numbers of mutations in recombinants (p=0.08).

To investigate whether recombinants displayed a selective advantage as compared to their likely parental strains, we determined replicative capacity (RC), a component of viral fitness. After determining the RCs of representative variants obtained in 2000, we stratified and compared their RCs according to their resistance-associated mutations (Table 3A). The mean RC of variants bearing both the A98V and G190S mutations was 12%, which not only fell in the unfit range, but was also significantly lower than that of other strains (p=0.007; RC≥50%, fit; RC 20–49%, intermediate; RC<20%, unfit). These results are consistent with the finding that the A98V mutation was present among likely parental variants, but was detected at only one time point; analyses showed that sequences encoding the A98V mutation were not inherited by the recombinants (Fig. 2A–C). Comparison of the RCs of recombinants to those of their likely parental strains showed that recombinant strains displayed RCs in the fit range, although a large proportion of the parental strains was unfit (Table 3B). These results support the hypothesis that recombination not only confers drug resistance, but may also confer increased viral fitness, thus permitting chimeric strains to survive under selective pressure.

Table 3A.

Resistance Mutations and Replicative Capacity of Variants Obtained in 2000

Table 3B.

Intrapatient Recombinants and Their Parental Variantsd

| Plasma parental variant | CVL parental variant | Recombinant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma-derived recombinant | |||

| Variant | 38P-200-3e | 38C-200-25 | 38P-700-12 |

| Resistance mutations | K103N | A98V, G190S | K103N, M184V, G190S |

| Genotypic and phenotypic resistance | NNRTI-R | NNRTI-R | NNRTI-R, 3TC-R |

| RC,† % | 87 | 11 | 58 |

| CVL fluid-derived recombinant | |||

| Variant | 38P-200-13 | 38C-200-1 | 38C-700-2 |

| Resistance mutations | K103N | A98V, G190S | K103N, M184V |

| Genotypic and phenotypic resistance | NNRTI-R | NNRTI-Rf | NNRTI, 3TC-R |

| RC, % | 19 | 9 | 83 |

Denotes the number and percentage of variants tested for RC that exhibited each single or combination of resistance-associated mutations.

RC≥50%, fit; RC 20–49%, intermediate; RC<20%, unfit.

The mean RC of variants bearing both the A98V and G190S mutations was significantly lower than that of the other variants (p=0.007).

Likely parental variants were identified by Bayesian analysis.

Variants are identified as follows: 38 denotes the patient number; P or C denotes plasma or cervicovaginal lavage as the site of origin of each variant; the numbers that follow denote the month and year the variant was obtained, so that 200 denotes February of 2000; and the final number denotes the particular variant obtained from that compartment on that date.

Phenotypic drug resistance could not be ascertained because of low RC.

RC, replicative capacity; CVL, cervicovaginal lavage; NVP, nevirapine; 3TC, lamivudine; R, high-level resistance.

Longitudinal analysis of HIV-1 variants during ART demonstrated that MDR intrapatient recombinants were common and persistent. These data illustrate how intrapatient recombination, in addition to point mutation, can contribute to the evolution of MDR HIV-1 in infected individuals. The present report identified multiple MDR recombinants emerging in a common clinical situation: an individual who initiated ART but did not achieve complete viral suppression. This retrospective analysis of the evolution of MDR resistance showed that although the subject was asymptomatic throughout the 4-year study period, with an increase in her CD4 count to 530 cells/mm3 and a reduction of HIV-1 RNA load by 1–2 logs (Table 1), she unfortunately also displayed persistent plasma viremia. Previous studies of HIV-1 resistance demonstrated that resistant viruses often evolve by acquiring a series of point mutations,18 each conferring a selective advantage by increasing resistance or fitness in a stepwise fashion. By comparing recombinants and their putative parental strains, this report illustrates how recombination in patients can lead to the acquisition of new genetic material, producing a virus exhibiting high-level resistance and high RC in one evolutionary leap (Tables 2 and 3). The persistence of phylogenetically related recombinants over a 4-year follow-up period attests to their survival under selective pressure.

This report also illustrates that viral recombination can contribute to the dissemination and persistence of viral genetic material from sites other than blood. Viral sequences initially obtained from the female genital tract, including those conferring drug resistance, appeared commonly in recombinant HIV-1 variants in the blood. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings, particularly studies focused on ART-naive individuals initiating a variety of regimens currently in use. Such studies promise to increase our understanding of the prevalence of recombination between HIV-1 variants from different compartments and its impact upon multidrug resistance in infected individuals.

It is likely that the suboptimal adherence to HAART reported by the subject contributed to the development of MDR HIV-1 in this individual. A large study previously addressed the impact of adherence on response to HAART among patients initiating treatment during 2000–2004.19 The investigation showed that patients with incomplete virologic responses were at high risk for emergence of drug resistance and these responses were highly dependent on adherence level. Furthermore, a recent study of women in Kenya demonstrated that suboptimal adherence and development of plasma drug resistance were the strongest predictors of genital tract shedding of HIV-1 during HAART20; it is noteworthy that our study subject exhibited intermittent adherence, drug resistance, and genital tract shedding for at least 7 months after starting HAART.

The data presented here support the rationale for virologic monitoring and viral suppression to prevent the emergence of drug resistance. Recombination requires that host cells be dually infected with different viruses,5 and higher HIV-1 loads increase the likelihood of intrapatient recombination. Common polymorphisms in the RT gene including the M184V mutation, which was prevalent in the study patient, can both increase the frequency of viral recombination and decrease the point mutation rate.21,22 Furthermore, superinfection followed by recombination has also been documented in infected individuals,8,9 and is the probable source of a panresistant HIV-1 strain.12

The issue of virologic monitoring to help prevent resistance is particularly timely in resource-limited settings, where the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that treatment failure be defined by clinical and CD4 criteria alone.2,23,24 Current WHO criteria, however, can be inadequate to predict virologic failure during ART.23 Treatment failure and HIV-1 drug resistance have now been documented in resource-limited as well as industrialized countries, leading to recommendations for laboratory testing and regular virologic monitoring of all patients taking ART.2,24

Research on HIV-1 resistance and recombination in patients benefits from analysis of individual viral variants. Minority HIV-1 strains bearing discrete, linked mutations have been identified, and can serve as reservoirs for novel resistance genotypes.25 In this study, analysis of individual viral genomes permitted us to identify distinct, recombinant, MDR HIV-1 genomes and their likely parental strains. The recent development of massively parallel pyrosequencing has enabled investigators to identify rare HIV-1 drug resistance mutations.4 Pyrosequencing, however, was not well suited to the analyses reported here because it generally yields genomic sequences of approximately a few hundred nucleotides; documentation of recombination and multidrug resistance in this study, by contrast, required analysis of the linkage of mutations on 1.6-kb genomic fragments encompassing the HIV-1 protease-RT region. Advances in pyrosequencing promise to make this technique more suitable for future studies of viral recombination as new platforms aim to yield longer sequences.

All recombinants in this study were identified as such by using three computational methods: SimPlot, BDCP analysis, and GARD. The BDCP framework was developed specifically to detect recombinants and locate their breakpoints.14,15 This method identified recombinant variants and the most likely parental strains, which were analyzed further in comparisons of putative parental and recombinant viruses (Table 3B).

Although some degree of recombination during both reverse transcription and PCR is inevitable given current laboratory methods, the likelihood that the chimeric variants described here arose in the patient is very high for a number of reasons. First, our methods are based upon a series of control measures taken to minimize PCR-mediated recombination; these include endpoint dilution of cDNA before amplification, controlled reaction conditions, and separate handling of plasma and CVL specimens during every stage of analysis.10,13 In a previous study, we performed a quantitative evaluation of the ability of the limiting dilution method to isolate single viral genomes, and demonstrated that the templates in our PCR experiments were very likely to be individual genomes.11 Amplification of a template consisting of a single genome diminishes the opportunity for PCR-mediated recombination to occur. Furthermore, the recombinants described here generally displayed evolutionary advantages as compared to their parental strains including high-level resistance to the patient's ART regimen and RC in the fit range; these findings support the idea that they arose in the patient rather than during PCR.

Additional data supporting the recombinants' origin in vivo is the configuration of the phylogenetic tree formed by all variants in the study (Fig. 3). Most of the recombinants clustered on one branch of the tree, with variants isolated over a span of years showing a high degree of relatedness. Genomes arising randomly by PCR-mediated recombination are unlikely to exhibit consistent evolutionary benefits as compared to their forbears nor to cluster so closely. Together, these findings strongly support the concept that the recombinant genomes characterized here arose in the patient, with their progeny persisting in the viral population over 4 years.

In summary, this study demonstrates that in viremic individuals, recombination as well as mutation can contribute to the rapid development of MDR HIV-1, which carries implications for HIV-1 transmission and clinical outcomes during ART.

GenBank Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences described in this study are DQ133606–DQ133701 and FJ822891–FJ822960.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study patient for her participation, Esther Robison and Tina Alford for patient interviews and medical record abstraction, the Wadsworth Center Molecular Genetics Core for sequencing, Penelope Huggins for technical help, Monica Parker for scientific discussions, and Andy Bentley for assistance with the figures. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01AI52015, R01GM086887, and U01AI/DE35004).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Richman DD. Morton SC. Wrin T. Hellmann N. Berry S. Shapiro MF. Bozzette SA. The prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance in the United States. AIDS. 2004;18:1393–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131310.52526.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoare A. Kerr SJ. Ruxrungtham K. Law MG. Cooper DA. Phanuphak P. Wilson DP. Hidden drug resistant HIV to emerge in the era of universal treatment access in Southeast Asia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malim MH. Emerman M. HIV-1 sequence variation: Drift, shift, and attenuation. Cell. 2001;104:469–472. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitsuya Y. Varghese V. Wang C. Liu TF. Holmes SP. Jayakumar P. Gharizadeh B. Ronaghi M. Klein D. Fessel WJ. Shafer RW. Minority human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants in antiretroviral-naive persons with reverse transcriptase codon 215 revertant mutations. J Virol. 2008;82:10747–10755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01827-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu WS. Temin HM. Genetic consequences of packaging two RNA genomes in one retroviral particle: Pseudodiploidy and high rate of genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1556–1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu Z. Gao Q. Faust EA. Wainberg MA. Possible involvement of cell fusion and viral recombination in generation of human immunodeficiency virus variants that display dual resistance to AZT and 3TC. J Gen Virol. 1995;76(Pt 10):2601–2605. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellam P. Larder BA. Retroviral recombination can lead to linkage of reverse transcriptase mutations that confer increased zidovudine resistance. J Virol. 1995;69:669–674. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.669-674.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang G. Weiser B. Kuiken C. Philpott S. Rowland-Jones S. Plummer F. Kimani J. Shi B. Kaul R. Bwayo J. Anzala O. Burger H. Recombination following superinfection by HIV-1. AIDS. 2004;18:153–159. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chohan B. Lavreys L. Rainwater SM. Overbaugh J. Evidence for frequent reinfection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 of a different subtype. J Virol. 2005;79:10701–10708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10701-10708.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemal KS. Foley B. Burger H. Anastos K. Minkoff H. Kitchen C. Philpott S. Gao W. Robison E. Holman S. Dehner C. Beck S. Meyer W. Landay A. Kovacs A. Bremer J. Weiser B. HIV-1 in genital tract and plasma of women: compartmentalization of viral sequences co-receptor usage, and glycosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12972–12977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134064100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi B. Kitchen C. Weiser B. Mayers D. Foley B. Kemal K. Anastos K. Suchard M. Parker M. Brunner C. Burger H. Evolution and recombination of genes encoding HIV-1 drug resistance and tropism during antiretroviral therapy. Virology. 2010;404:5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blick G. Kagan RM. Coakley E. Petropoulos C. Maroldo L. Greiger-Zanlungo P. Gretz S. Garton T. The probable source of both the primary multidrug-resistant (MDR) HIV-1 strain found in a patient with rapid progression to AIDS and a second recombinant MDR strain found in a chronically HIV-1-infected patient. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1250–1259. doi: 10.1086/512240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang G. Zhu G. Burger H. Keithly JS. Weiser B. Minimizing DNA recombination during long RT-PCR. J Virol Methods. 1998;76:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suchard MA. Weiss RE. Dorman KS. Sinsheimer JS. Inferring spatial phylogenetic variation along nucleotide sequences: A multiple change-point model. J Am Stat Assoc. 2003;98:427–431. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minin VN. Dorman KS. Fang F. Suchard MA. Dual multiple change-point model leads to more accurate recombination detection. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3034–3042. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lole KS. Bollinger RC. Paranjape RS. Gadkari D. Kulkarni SS. Novak NG. Ingersoll R. Sheppard HW. Ray SC. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J Virol. 1999;73:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosakovsky Pond SL. Posada D. Gravenor MB. Woelk CH. Frost SD. Automated phylogenetic detection of recombination using a genetic algorithm. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1891–1901. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suné C. Brennan L. Stover DR. Klimkait T. Effect of polymorphisms on the replicative capacity of protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 variants under drug pressure. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima DV. Harrigan R. Murray M. Moore DM. Wood E. Hogg RS. Montaner JSG. Differential impact of adherence on long-term treatment response among naïve HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2008;22:2371–2380. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328315cdd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham SM. Masese L. Gitau R. Jalalian-Lechak Richardson BA. Peshu N. Mandaliya K. Kiarie JN. Jaoko W. Ndinya-Achola J. Overbaugh J. McClelland RS. Antiretroviral adherence and development of drug resistance are the strongest predictors of genital HIV-1 shedding among women initiating treatment. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1538–1542. doi: 10.1086/656790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolenko GN. Svarovskaia ES. Delviks KA. Pathak VK. Antiretroviral drug resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase increase template-switching frequency. J Virol. 2004;78:8761–8770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8761-8770.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wainberg MA. Drosopoulos WC. Salomon H. Hsu M. Borkow G. Parniak M. Gu Z. Song Q. Manne J. Islam S. Castriota G. Prasad VR. Enhanced fidelity of 3TC-selected mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1996;271:1282–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mee P. Fielding KL. Charalambous S. Churchyard GJ. Grant AD. Evaluation of the WHO criteria for antiretroviral treatment failure among adults in South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1971–1977. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e4cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith DM. Schooley RT. Running with scissors: Using antiretroviral therapy without monitoring viral load. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1598–1600. doi: 10.1086/587110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecossier D. Shulman NS. Morand-Joubert L. Shafer RW. Joly V. Zolopa AR. Clavel F. Hance AJ. Detection of minority populations of HIV-1 expressing the K103N resistance mutation in patients failing nevirapine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:37–42. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]