Abstract

A critical step in HIV-1 transmission studies is the rapid and accurate identification of epidemiologically linked transmission pairs. To date, this has been accomplished by comparison of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified nucleotide sequences from potential transmission pairs, which can be cost-prohibitive for use in resource-limited settings. Here we describe a rapid, cost-effective approach to determine transmission linkage based on the heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA), and validate this approach by comparison to nucleotide sequencing. A total of 102 HIV-1-infected Zambian and Rwandan couples, with known linkage, were analyzed by gp41-HMA. A 400-base pair fragment within the envelope gp41 region of the HIV proviral genome was PCR amplified and HMA was applied to both partners' amplicons separately (autologous) and as a mixture (heterologous). If the diversity between gp41 sequences was low (<5%), a homoduplex was observed upon gel electrophoresis and the transmission was characterized as having occurred between partners (linked). If a new heteroduplex formed, within the heterologous migration, the transmission was determined to be unlinked. Initial blind validation of gp-41 HMA demonstrated 90% concordance between HMA and sequencing with 100% concordance in the case of linked transmissions. Following validation, 25 newly infected partners in Kigali and 12 in Lusaka were evaluated prospectively using both HMA and nucleotide sequences. Concordant results were obtained in all but one case (97.3%). The gp41-HMA technique is a reliable and feasible tool to detect linked transmissions in the field. All identified unlinked results should be confirmed by sequence analyses.

Introduction

One of the critical steps in the development of an efficient vaccine to decrease HIV transmission is a better understanding of the viruses and mechanisms involved in initiating the process of heterosexual transmission.1 In this regard, important information can be gained from studies of newly infected individuals near the time of transmission.2–4 Characterization of the transmitted virus could facilitate the identification of common characteristics that form the basis for the design of new vaccines that generate an appropriate immune response.2–6 A comparison of viral populations from different tissue compartments from the donor with ones circulating at the earliest times in the recipient could provide clues as to the nature of the viruses that have crossed the mucosal barriers and the initial immune response to this virus population.2–4,7–11

One of the optimal ways to study the sociological, immunological, and virological correlates of heterosexual transmission is the follow-up of serodiscordant couples,5,12–14 since, despite counseling, HIV transmission still occurs, albeit at a substantially lower rate.13 A key aspect in the study of transmission among serodiscordant couples is the ability to confirm, with a high level of confidence, the epidemiological linkage of HIV-1 transmission between partners.15 To understand the virological correlates of HIV-1 transmission from the chronically infected partner to a new recipient,2–4,7,9–11 it is critical to determine as quickly and accurately as possible in the field whether the transmission is linked.

The Rwanda Zambia HIV Research Group (RZHRG) was initiated at Projet San Francisco (PSF) in 1986 and extended to include the Zambia-Emory HIV Research Project (ZEHRP) in 1994. RZHRG provides cohabiting couples with voluntary counseling and testing, long-term monitoring, and health care in Kigali and Lusaka, the capital cities of Rwanda and Zambia, respectively.12,16,17 A genetic characterization, through nucleotide sequencing, in two independent regions of the HIV genome among 149 HIV-1 transmission events in Zambia showed that in 87% of the transmission pairs, the viruses in the chronically infected and newly infected partners were highly related.15 These transmissions were classified as epidemiologically linked and represent transmission from one partner to the other in the cohabiting couple. By contrast, 13% of transmissions were characterized as epidemiologically unlinked and represented transmission of HIV-1 from a nonspousal partner.15 Similar proportions of linked and unlinked transmissions have been observed for subtype-A HIV-1 transmission in Rwandan discordant couples.17 Here we describe the development and validation of a rapid procedure, based on the principle of the heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) in the HIV-1 gp41 env region, and its application to the study of the epidemiologic linkage of transmission between partners. These analyses were carried out at two different field sites in Zambia and Rwanda where subtype C and subtype A HIV-1 are predominant.

Our hypothesis was that the heterologous gp41 duplex should migrate at the same level as the controls if the virus population in one partner was derived from the viral quasispecies in the other partner, since our previous study showed that in a majority of epidemiologically linked transmission pairs, shortly after transmission, the median diversity between the two populations was only 1.5%. In cases in which partners are infected by divergent viruses, we expected the migration of the heteroduplex would be decreased proportionally to the divergence of the two viruses in the gp41 region. The results of these studies show that the gp41-based HMA approach represents a reliable screening method to determine epidemiological linkage. However, these data also indicate that transmissions characterized as unlinked by gp41-HMA should be confirmed by sequence analysis.

Materials and Methods

Study population and samples

Couples HIV voluntary counseling and testing (CVCT) has been previously described.12,16

For establishment of HMA analysis in the field, in addition to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) equipment (thermocycler, gel casts, powerpack, and other small equipment) that is necessary for both HMA and sequencing, vertical gel casts (Mini-Protean, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to be used with acrylamide gels were supplied to the sites to perform HMA. Six couples can be tested concomitantly within 3 h by a well-trained technologist for a cost of less than 2 dollars per test, making this cost effective.

For the Evaluation Study, buffy coats were collected without identifiers from each partner of concordant HIV-1-positive couples identified through CVCT screening and stored in RNA Later (Ambion, TX) at −80°C. For the Prospective Study, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) DNA samples were collected from each partner of an enrolled discordant couple at the time infection of the initially seronegative partner was detected.2,3

For the preliminary evaluation of a gp41-based HMA approach to characterize intrasubtype epidemiological linkage in the field, 19 pairs of samples that differed in genetic diversity from 5.8% to 16.7% were selected from existing unlinked transmission pairs in the ZEHRP cohort. In parallel, genetic diversity was determined through PCR amplicon nucleotide sequencing and pairwise distance calculations.18

A total of 102 transmission pairs from the Rwandan cohort from PSF were chosen for a blinded cross-sectional assessment of the HMA technique for linkage analysis (Evaluation Study). The epidemiological linkage for these samples had previously been determined using sequencing and phylogenetic analyses of gp41 amplicons.

For the Prospective Study, linkage was performed in real time in the field using the gp41-based HMA as closely as possible to the time of transmission and the results were compared with sequence analyses. These new transmission pairs were identified at ZEHRP in Lusaka, Zambia, and at PSF, in Kigali, Rwanda from 2006 to 2007.

All research protocols were approved by the National Ethics Committee in Kigali, Rwanda, and the University of Zambia, School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee in Lusaka, Zambia, and by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Nested PCR amplification, autologous and heterologous HMA in the gp41 env region

PBMC DNA was extracted from 1.5 ml buffy coat samples stored in RNA later (Ambion, TX) using QIAamp DNA Blood Midi kits (Qiagen, CA) as specified by the manufacturer. An ∼400-bp fragment in the conserved gp41 region was amplified with nested PCR primers19 and reaction conditions previously described.15 Previous studies comparing different regions of the HIV-1 genome demonstrated that the gp41 region was most suitable for establishing linkage, given a high sensitivity and specificity.15 Moreover, the primer sequences used for PCR amplification of this region are highly conserved in HIV strains within the Zambian and Rwandan cohort and therefore provide a reliable region for comparison.

The principle of autologous gp41-HMA is to evaluate the diversity (heteroduplex formation) within one individual. However, heterologous HMA is the evaluation of diversity between individuals and, in our study, between both partners of the same couple. Thus, PCR amplicons from each partner in a transmission pair were compared to a mixture containing PCR products from both partners to define the linkage of transmission within couples. Heteroduplex analyses were performed similar to that described by Agwale et al.20 for subtype analyses. Briefly, second round gp41 PCR products amplified from patients were used directly in the heteroduplex assay.4,5 The heterologous comparison was accomplished with 10 μl of each sample mixed with 6 μl of Orange G buffer (Trevigen Co, MD) and 5 μl of 5×annealing buffer [1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7. 8), 20 mM EDTA]. The autologous comparison was performed using 20 μl of the acutely infected individual's amplicon over serial time points. DNA duplexes were formed by denaturing at 95°C for 2 min and rapidly annealing in ice water for at least 5 min.6 Heteroduplexes were resolved on nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels (acrylamide:bis, 37.5:1) in TBE for 2 h at 80 V. Gels were then stained with ethidium bromide solution and examined under UV light for the presence of heteroduplexes.

Comparison of heteroduplex mobility for analysis of linkage between partners

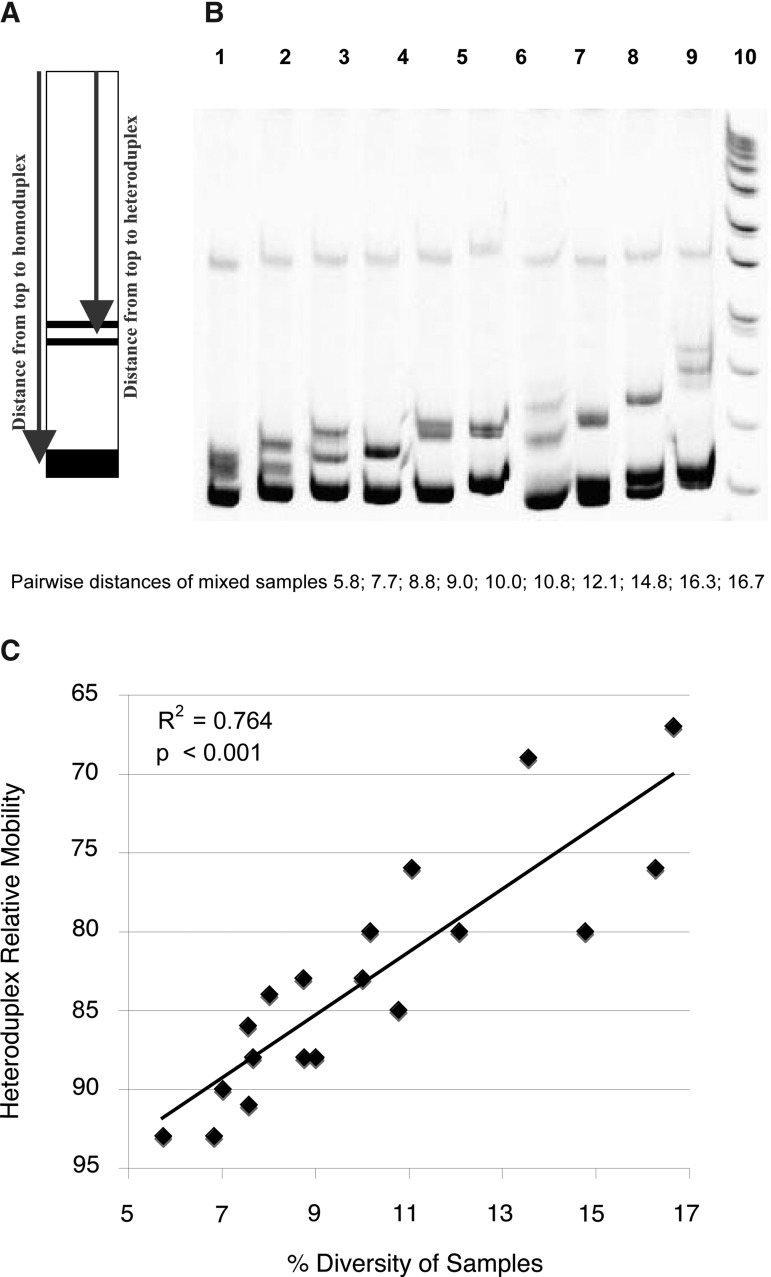

To establish the usable range of the gp41-HMA for intrasubtype analyses, we performed heterologous HMA on 19 pairs of viruses from known partners with already evaluated pairwise distance diversity, and calculated the relative migration of the resulting heteroduplexes relative to their homoduplex (Fig. 1A). These calculations were done directly on the HMA gel pictures using the Doc-ItLs program (UVP, Cambridge, UK) that allows distance calculations. The relative mobility for each sample was defined as the ratio between the migration distance for heteroduplexes and that for homoduplexes times 100 (percentage).

FIG. 1.

Assessment of heterologous heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) to establish linkage. (A) Heteroduplex mobilities were calculated as the average distance of migration of the two heteroduplex bands divided by the distance of migration of the homoduplex bands times 100 (%).33 (B) Heterologous HMA profiles for mixed unrelated samples. The gp41 PCR amplicons from 19 subjects with diversities ranging from 5.8% to 16.7% were mixed together in order to mimic epidemiologically unlinked transmission and to determine whether the HMA technique was sensitive enough to cover this range of diversity. Lanes 1 through 10 shows mixtures of amplicons with pairwise distances of 5.8, 7.7, 8.8, 9.0, 10.0, 10.8, 12.1, 14.8, 16.3, and 16.7, respectively. (C) Relationship between HMA and pairwise distances. Relative mobilities plotted against pairwise distance and the linear relationship between these two variables for all 19 samples.

For the prospective study, autologous HMA of PCR-amplified samples from the newly HIV-1-infected individual and their partner, at the time when the transmission was detected, were compared with a heterologous HMA using a mixture of samples from each partner. Mixed samples with a heteroduplex band, clearly separated from the homoduplex band, in the heterologous HMA were classified as being derived from an unlinked transmission since it should depict a diversity of more than 5%21 and that 5% of diversity could not be due to the quasispecies diversity.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

gp41 PCR products were purified and sequenced on both strands and then aligned by using the CLUSTAL X multiple sequences alignment program as previously described.3 Phylogenetic trees based on the existing gp41 sequences were constructed by the neighbor-joining method included in the PHYLIP package. Linkage analyses were carried out as previously described.15 Briefly, uncorrected nucleotide sequence pairwise distances (PWD) were calculated for each transmission pair and compared to the mean sequence distances calculated for a reference sequence set of the same subtype from the Los Alamos Sequence Database in the corresponding genomic region. Two standard deviations were subtracted from this mean distance and all values below were defined as linked transmissions. In addition to these analyses, phylogenetic trees were constructed to confirm that viral sequences from both partners branched together. In rare cases sequences from both partners were found to branch together with a high bootstrap value despite exhibiting a diversity exceeding the PWD cut-off value. In these cases the phylogenetic analysis overrode the PWD analysis and the couple was classified as linked. All sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JX218995–JX219268.

Results

Preliminary evaluation of gp41-HMA for intrasubtype analyses

To apply the gp41-based HMA assay, previously used to determine subtype,20 to an intrasubtype epidemiological linkage technique, it was necessary to determine the sensitivity of the approach. A total of 19 pairs of gp41 PCR products from subtype C Zambian subjects with PWDs ranging from 5.8% to 16.7%, as previously determined by sequencing, were mixed together (heterologous HMA) and electrophoresed on a polyacrylamide gel after heteroduplex formation. A gel of 10 representative samples is shown in Fig. 1B. Migration distance was inversely proportional to PWD (Fig. 1C). Moreover, a heteroduplex was seen even with a mixture of gp41 amplicons that exhibited a pairwise distance of 5.8% (Fig. 1B), which demonstrated that the sensitivity of the technique was sufficient to distinguish between unlinked couples for whom the median pairwise distance has been previously evaluated at 8.8%.15

Evaluation study: use of gp41-HMA to analyze linkage between partners

To evaluate the potential of gp41-HMA to determine linkage between partners, both in recent transmission pairs and established couples, 204 extracted DNA samples from 102 HIV-concordant positive Rwandan couples (Table 1) were selected and tested by gp41-HMA in a blinded fashion. Autologous HMAs from each partner were used as controls. Our hypothesis was that the heterologous gp41 duplex should migrate at the same level as the controls if the virus population in one partner was derived from the viral quasispecies in the other partner, since our previous study showed that in a majority of epidemiologically linked transmission pairs, shortly after transmission, the median diversity between the two populations was only 1.5%. However, that same study showed that if the virus population in the recipient was not derived from the spouse, the median genetic diversity exceeded 8%.15 Thus, in the latter case where partners are infected by divergent viruses, the migration of the heteroduplex will be decreased proportionally to the divergence of the two viruses.

Table 1.

Linkage Results Evaluated Through Sequencing and Heteroduplex Mobility Assay for the Evaluation Study

| Number | Couple ID | Pairwise distance (%) | Linkage through sequencing | Linkage through HMA | Homoduplex distance heterologousa | Heteroduplex distance heterologousa | Heteroduplex relative mobility (%) | Presence of autologous heteroduplexb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R4 | 3.61 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 2 | R5c | 3.87 | Linked | Unlinked | 1225 | 1123 | 91.7 | No |

| 3 | R7 | 2.04 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 4 | R9 | 4.60 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 5 | R10 | 1.26 | Linked | Linked | Yes M | |||

| 6 | R13 | 3.72 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 7 | R18 | 1.27 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 8 | R21 | 1.80 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 9 | R24 | 3.90 | Linked | Linked | Yes F | |||

| 10 | R25 | 2.50 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 11 | R26 | 1.53 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 12 | R27 | 2.81 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 13 | R32 | 1.77 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 14 | R33 | 1.52 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 15 | R34 | 4.14 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 16 | R35 | 2.54 | Linked | Unlinked | 950 | 873 | 91.9 | No |

| 17 | R36 | 0 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 18 | R42 | 8.58 | Linked | Unlinked | 1148 | 969 | 84.4 | Yes F |

| 19 | R43 | 0.50 | Linked | Linked | Yes F | |||

| 20 | R146 | 0.75 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 21 | R148 | 3.87 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 22 | R150 | 3.83 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 23 | R151 | 3.34 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 24 | R152 | 1.78 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 25 | R155 | 2.04 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 26 | R157 | 4.67 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 27 | R160 | 0.05 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 28 | R161 | 1.26 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 29 | R162 | 1.01 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 30 | R163 | 3.09 | Linked | Linked | Yes M | |||

| 31 | R165 | 2.56 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 32 | R166 | 3.33 | Linked | Linked | Yes M | |||

| 33 | R168 | 0.25 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 34 | R171 | 1.26 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 35 | R173 | 7.69 | Linked | Unlinked | 1265 | 1065 | 84.2 | No |

| 36 | R175 | 2.33 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 37 | R176 | 2.82 | Linked | Linked | Yes M | |||

| 38 | R180 | 0 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 39 | R181 | 0.50 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 40 | R182 | 5.26 | Linked | Unlinked | 1313 | 1130 | 86.1 | Yes F |

| 41 | R185 | 2.83 | Linked | Unlinked | 938 | 847 | 90.3 | No |

| 42 | R186 | 2.29 | Linked | Unlinked | 1313 | 1241 | 94.5 | No |

| 43 | R189 | 1.52 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 44 | R191 | 4.69 | Linked | Linked | Yes M | |||

| 45 | R194 | 2.80 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 46 | R197 | 3.07 | Linked | Linked | Yes M | |||

| 47 | R203 | 1.28 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 48 | R204 | 7.16 | Linked | Unlinked | 1260 | 1169 | 92.8 | Yes F |

| 49 | R207 | 1 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 50 | R209 | 1.77 | Linked | Linked | Yes F | |||

| 51 | R210 | 2.30 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 52 | R212 | 4.70 | Linked | Linked | Yes F | |||

| 53 | R214 | 2.81 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 54 | R215 | 5.23 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 55 | R216 | 4.40 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 56 | R218 | 1.78 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 57 | R221 | 4.42 | Linked | Unlinked | 1252 | 1160 | 92.7 | No |

| 58 | R222 | 2.04 | Linked | Linked | ||||

| 59 | R224 | 1.78 | Linked | Linked | No | |||

| 60 | R226 | 4.12 | Linked | Unlinked | 1262 | 1155 | 91.5 | No |

| 61 | R227 | 2.31 | Linked | Linked | Yes F | |||

| 62 | R1 | 18.15 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1163 | 865 | 74.4 | No |

| 63 | R6 | 15.50 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1247 | 810 | 65.0 | Yes M and F |

| 64 | R8 | 16.85 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 993 | 686 | 69.1 | No |

| 65 | R11 | 10.77 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 983 | 811 | 82.5 | No |

| 66 | R14 | 15.60 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1203 | 935 | 77.7 | No |

| 67 | R16 | 14.42 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1347 | 1064 | 79.0 | No |

| 68 | R17 | 12.67 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1284 | 862 | 67.1 | No |

| 69 | R20 | 9.20 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 867 | 578 | 66.7 | Yes M |

| 70 | R22 | 6.33 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1254 | 1112 | 88.7 | No |

| 71 | R23 | 20.55 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1265 | 811 | 64.1 | No |

| 72 | R29 | 7.72 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 873 | 763 | 87.4 | No |

| 73 | R30 | 7.22 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 869 | 749 | 86.2 | Yes F |

| 74 | R31 | 11.31 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 785 | 592 | 75.4 | No |

| 75 | R41 | 8.35 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1104 | 939 | 85.1 | No |

| 76 | R149 | 7.05 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1317 | 1191 | 90.4 | No |

| 77 | R153 | 10.48 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1251 | 829 | 66.3 | No |

| 78 | R158 | 15.65 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1282 | 965 | 75.3 | No |

| 79 | R164 | 6.05 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1014 | 923 | 91.0 | Yes M |

| 80 | R167 | 16.60 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1289 | 980 | 76.0 | No |

| 81 | R169 | 7.80 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1141 | 946 | 82.9 | No |

| 82 | R170 | 7.73 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1317 | 1115 | 84.7 | No |

| 83 | R174 | 7.21 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 946 | 814 | 86.0 | No |

| 84 | R178 | 16.22 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1298 | 995 | 76.7 | No |

| 85 | R179 | 16.39 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1262 | 896 | 71.0 | No |

| 86 | R183 | 14.94 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1275 | 878 | 68.9 | No |

| 87 | R184 | 14.66 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1255 | 972 | 77.5 | Yes F |

| 88 | R187 | 8.33 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1137 | 926 | 81.4 | No |

| 89 | R188 | 8.88 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1159 | 1000 | 86.3 | No |

| 90 | R190 | 10.69 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1324 | 1087 | 82.1 | Yes F |

| 91 | R192 | 13.10 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1163 | 843 | 72.5 | Yes M |

| 92 | R196 | 10.70 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1261 | 941 | 74.6 | Yes M |

| 93 | R198 | 9.14 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1239 | 992 | 80.1 | Yes F |

| 94 | R200 | 10.32 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1181 | 948 | 80.3 | No |

| 95 | R201 | 11.93 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1143 | 901 | 78.8 | No |

| 96 | R202 | 15.65 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1162 | 786 | 67.6 | No |

| 97 | R205 | 21.03 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1266 | 953 | 75.3 | Yes M |

| 98 | R206 | 9.75 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1284 | 1104 | 86.0 | No |

| 99 | R208 | 6.90 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1178 | 1073 | 91.1 | No |

| 100 | R217 | 8.86 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1296 | 1177 | 90.8 | No |

| 101 | R223 | 10.14 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1126 | 874 | 77.6 | No |

| 102 | R225 | 18.89 | Unlinked | Unlinked | 1045 | 755 | 72.2 | No |

Units used to measure heteroduplex and homoduplex mobilities were generated by DocIT analysis of the HMA gels.

Cells in italics indicate when a heteroduplex was seen in the autologous HMA and for which partner.

Bold squares indicate results that are discrepant between gp41 heterologous HMA and sequencing.

After unblinding the results, all of the 102 linkage determinations evaluated through gp41-HMA were identical to the ones evaluated by sequencing except for 10 couples (90% concordance) (Table 1, Fig. 2). Fifty-one couples were identified as linked by gp41-HMA and 51 as unlinked, whereas 61 were determined to be linked and 41 unlinked through sequencing and phylogenetic tree analyses (Table 1, Fig. 2). Except for the discrepant cases, all the linked couples had diversities below 5.23% (median 2.01%). One unique case (R215) did not generate heteroduplexes and was classified as linked by HMA and sequencing despite having a PWD greater than 5% (5.23%). All the unlinked couples had diversities exceeding 6.05% (median 10.07%) (Table 1).

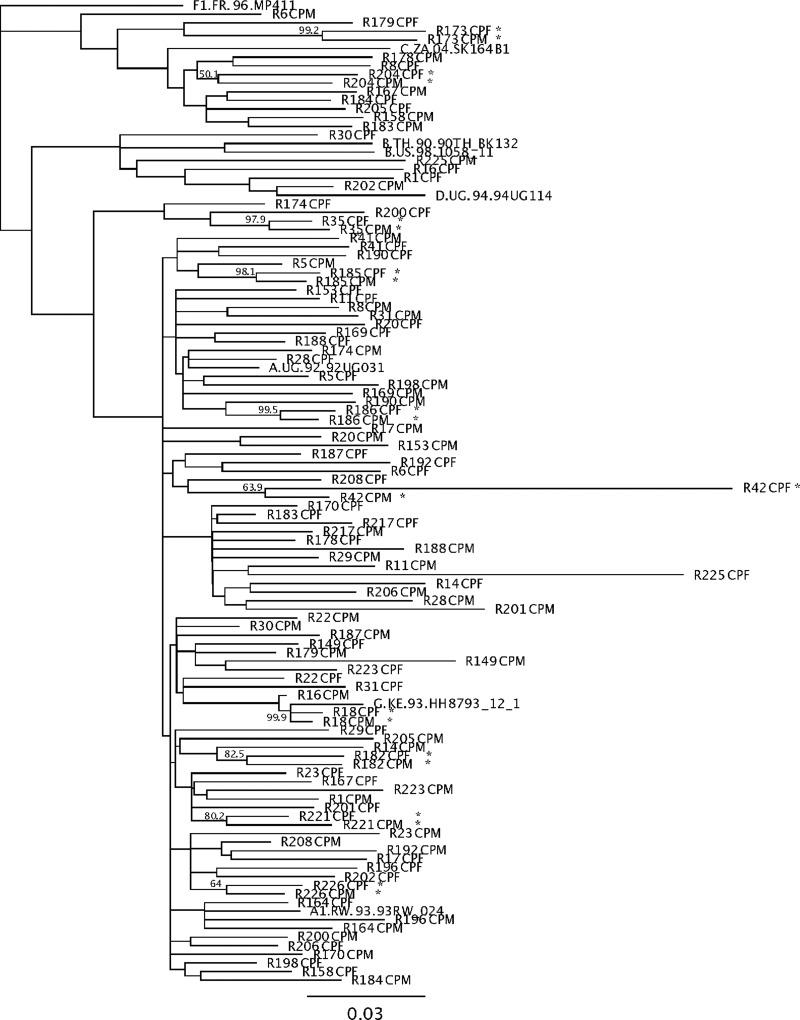

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of couples tested in the evaluation study. This neighbor-joining tree shows all the couples that were classified as epidemiologically unlinked by gp41-HMA. The 10 couples with asterisks are those that gave discrepant results with sequencing (Table 1).

The 10 discrepant results identified by bold squares in Table 1 had a diversity ranging from 2.29% to 7.69%. Four of them had diversities exceeding 5%, which is the threshold of the technique according to Upchurch et al.21 Seven of them had relative mobilities exceeding 90%, meaning that the observed heteroduplexes were very close to homoduplexes. In all 10 cases, HMA results revealed that the couples were unlinked while sequencing argued they were linked (asterisk, Fig. 2).

The efficiency of the gp41-HMA technique to analyze linkage in the case of sequence-verified epidemiologically linked transmissions is 83.6% (51/61), whereas the efficiency of the technique to detect diversity greater than 5% is 90.2% (92/102). On the other hand, the specificity of the technique to detect linked transmissions is 100% since all the transmissions identified as linked by gp41-HMA were confirmed by sequencing.

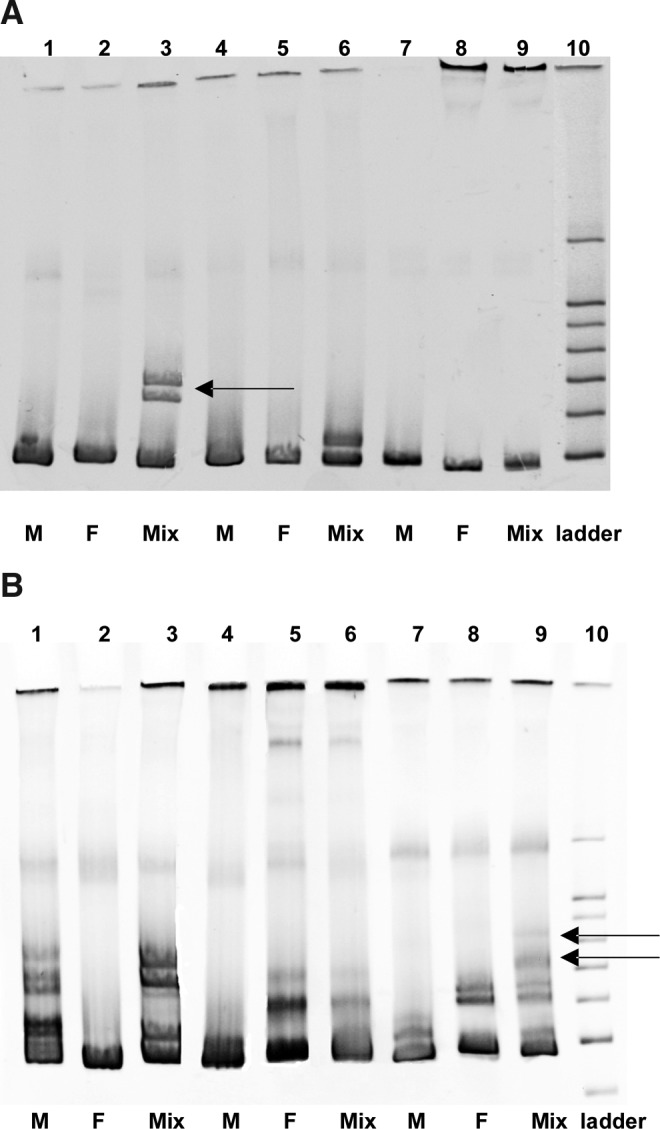

Examples of gp41 autologous and heterologous HMAs are shown in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3, lane 3 (transmission pair R158) shows the appearance of clear heteroduplexes (arrow) in the heterologous HMA that are not present in either the male (lane 1) or female (lane 2) autologous HMAs, indicative of an unlinked transmission. Sequencing confirmed a high diversity between the male and female variants (15.65%) (Table 1). Lanes 4, 5, and 6 show autologous and heterologous HMA displayed in the case of an unlinked transmission when the diversity between male and female variants was low (transmission pair R149, 7.05%). In contrast, lanes 7, 8, and 9 (transmission pair R207) provide a clear example of a linked transmission since the heterologous HMA lacks a heteroduplex band (sequence diversity, 1.00%) (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

A prospective study of HMA for linkage analysis. (A) Autologous (M and F) and heterologous (Mix) HMA profiles for unlinked with high diversity (Couple R158, 15.65%), unlinked with low diversity (Couple R149, 7.05%), and linked transmissions, respectively (Couple R207, 1.00%). The heteroduplexes in heterologous HMA for R158 and R149 demonstrates an unlinked transmission. (B) Autologous and heterologous HMA profiles in the context of high diversity within an individual. R166 (lanes 1, 2, and 3) and R209 (lanes 4, 5, and 6) are linked couples with heteroduplexes present in the autologous HMA for male and female, respectively. For both couples, the heterologous HMA shows heteroduplexes in the same positions as those in the autologous HMA. R6 was classified as unlinked because a new heteroduplex is seen in the heterologous HMA (see arrows). The pairwise distance for this couple is 15.50%.

It should be noted, however, that a high level of heterogeneity within the gp41 sequence of a chronically infected partner can result in a complex heteroduplex pattern in the autologous HMA. As can be observed in Fig. 3B, the HMA profiles of transmission pairs R166 and R209 (lanes 1, 2, 3 and 4, 5, 6, respectively) are more complex since in these cases the male autologous HMA (lane 1) and the female autologous HMA (lane 5) exhibit strong heteroduplex bands. Nevertheless, following mixing of the male and female amplicons (heterologous HMA) no new heteroduplex bands were observed, consistent with a linked transmission pair.

For transmission pair R6, both partners exhibited distinct heteroduplex bands in the autologous HMAs (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 and 8), but in this case the heterologous HMA (Fig. 3B, lane 9) contains additional heteroduplexes (arrows), which migrated more slowly, indicative of higher diversity. This transmission was thus classified as unlinked, and sequence analysis confirmed a diversity of 15.5% (Table 1). Even for these more complex cases, phylogenetic analyses of the sequences confirmed the linkage status of these transmissions (Fig. 2). It should be noted though that analysis of the phylogenetic tree and branching patterns was required to definitively establish the epidemiological link between partners in these more complicated cases. Indeed, some couples, although exhibiting a high diversity between partners, branched together with high bootstrap values on the tree, consistent with a linked transmission in which the viruses have diverged over time or exhibit hypermutation. This is the case for couples R42, R173, R182, and R204 (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Correlation between partners' diversity and relative mobility of heteroduplexes

To determine the correlation between relative mobility of gp41 heteroduplexes and PWDs, the migration of each heteroduplex identified in heterologous HMA was measured and expressed as a percentage of the homoduplex migration distance (relative mobility, Fig. 1A). The 51 confirmed unlinked transmission pairs in which a heteroduplex was identified by gp41-HMA were analyzed in this way and the relative mobility compared to the PWD for the gp41 coding sequences. Figure 4 shows these results and demonstrates a statistically significant association between the two parameters (R=0.657, p<0.0001).

FIG. 4.

Relationship between HMA and pairwise distances. Relative mobilities plotted against pairwise distance and the linear relationship between these two variables. Values were calculated for 51 couples with heteroduplexes in the heterologous gp41-HMA, with diversity ranging from 2.29% to 21.03%. Heteroduplex mobilities were calculated as the average distance of migration of the two heteroduplex bands divided by the distance of migration of the homoduplex bands times 100 (%)33 (Fig. 1A). Genetic distances were determined by the standard method of maximum likelihood in the program DNADIST from the PHYLIP Package.

Prospective study: use of gp41-HMA to prospectively analyze the epidemiological linkage of new transmission pairs

After validation of the gp41 HMA to analyze intrasubtype linkage of transmission in this random selection of concordant positive couples, we prospectively analyzed 37 new HIV transmission events that were detected in both the ZEHRP and PSF cohorts. The results of HMA were compared post hoc with the sequencing results from the same PCR amplicon (Table 2). A total of 25 newly infected individuals and their partners in Kigali and 12 in Lusaka were evaluated by the same technique. Among these 37 transmissions, 13 were male-to-female (MTF) and 12 female-to-male (FTM) transmissions in Kigali whereas for the transmissions in Lusaka, three were MTF and nine were FTM. Four transmissions in Kigali (16%) and two transmissions in Lusaka (16.7%) were unlinked.

Table 2.

Linkage Results Evaluated Through Sequencing and Heteroduplex Mobility Assay for the Prospective Study

| Number | Couple ID | Direction of transmission | Pairwise distance (%) | Linkage by sequencing | Linkage by gp41 HMA | Consistency between techniques | Presence of autologous heteroduplexa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R53 | MTF | 1.77 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 2 | R51 | FTM | 0.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 3 | R55 | FTM | 8.05 | Unlinked | Unlinked | Yes | |

| 4 | R75 | FTM | 7.01 | Unlinked | Unlinked | Yes | |

| 5 | R519 | FTM | 1.25 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 6 | R1142 | MTF | 0.25 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 7 | R554 | FTM | 1.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 8 | R342 | MTF | 4.76 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 9 | R254 | MTF | 2.77 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 10 | R881 | FTM | 1.26 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 11 | R976 | FTM | 10.8 | Unlinked | Unlinked | Yes | |

| 12 | R885 | MTF | 2.00 | Linked | Linked | Yes | Yes F |

| 13 | R889 | FTM | 1.25 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 14 | R283 | MTF | 0.50 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 15 | R977b | MTF | 3.76 | Linked | Unlinked | No | Yes M and F |

| 16 | R888 | MTF | 0.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 17 | R489 | MTF | 1.00 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 18 | R1135 | FTM | 0.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 19 | R516 | MTF | 1.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | Yes M |

| 20 | R269 | FTM | 1.00 | Linked | Linked | Yes | Yes M and F |

| 21 | R740 | FTM | 1.25 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 22 | R1637 | MTF | 7.32 | Unlinked | Unlinked | Yes | |

| 23 | R1879 | FTM | 1.26 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 24 | R497 | MTF | 0.50 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 25 | R1077 | MTF | 0.50 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 26 | Z326 | FTM | 2.26 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 27 | Z1083 | MTF | 0.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 28 | Z1550 | FTM | 7.27 | Linked | Linked | Yes | Yes F |

| 29 | Z1464 | FTM | 8.79 | Unlinked | Unlinked | Yes | |

| 30 | Z1167 | FTM | 1.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 31 | Z1480 | MTF | 0.25 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 32 | Z1006 | FTM | 1.75 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 33 | Z1008 | FTM | 2.51 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 34 | Z1047 | FTM | 9.77 | Unlinked | Unlinked | Yes | |

| 35 | Z1022 | FTM | 1.26 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 36 | Z634 | MTF | 1.27 | Linked | Linked | Yes | |

| 37 | Z1413 | FTM | 1.77 | Linked | Linked | Yes |

Cells in italics indicate when a heteroduplex was seen in the autologous HMA and for which partner.

Result that was discrepant between gp41 heterologous HMA and sequencing.

As shown in Table 2, out of the 37 linkage analyses performed using HMA, we observed identical linkage results to sequencing and phylogenetic analyses in 36 (97.3% concordance). In the one discrepant case (R977), the autologous HMAs for each partner displayed heteroduplexes because of a high level of G/A hypermutations22 and, thus, despite being linked, was misclassified as unlinked with the HMA technique.

Discussion

There are social and public health reasons for identifying linked and unlinked HIV-1 transmissions. The main purpose of this study was to develop a cost-effective tool that allows rapid screening in the field of transmission pairs for epidemiological linkage of the virus populations in both partners close to the time of transmission, as well as at additional times posttransmission. The applicability of this assay is intended for resource-limited settings and at no time during this study were the linkage results disclosed to the participants. This rapid classification provides the rationale for further investigation using full-length envelope sequencing on linked2,3 or unlinked couples18 that are followed differently according to their linkage status.

The gp41 region was chosen to perform HMA analyses since it was demonstrated to give high sensitivity and specificity19 and produce reliable heteroduplex profiles.20 The principle of autologous gp41-HMA is to evaluate the diversity (heteroduplex formation) within one individual. A similar procedure used in the gp120 env region was applied to identify divergent variants in a commercial sex worker cohort in Burkina Faso, leading to a report of the first two cases of superinfection in Africa.23 More recently, autologous HMA was validated in the gag region with the primers developed by Heyndricks et al. to identify dual infections.24–26 The evaluation of linkage in studies of HIV transmission is crucial as assumptions concerning transmission linkage based on patient self-reporting alone are unlikely to be accurate.12 Practically, this allows recruitment of volunteers into different studies according to the linkage results.

We first investigated the potential of the HIV-1 gp120 region for determining by HMA the epidemiological linkage of viruses in transmission pairs. However, due to the high variability of the gp120 region (single mutations and deletions) the results were generally not interpretable (data not shown). On the other hand, we have shown previously that for Zambia the median diversity of an epidemiologically unlinked transmission is 8.8% in the gp41 region compared to 1.5% for linked transmissions in our cohort.15 Because the threshold of detection of the HMA technique is just between these two values, it should allow a differentiation between linked and unlinked transmission pairs. With the purpose of identifying the limits of this technique for intrasubtype analyses, in contrast to its previous use for intersubtype studies, we mixed DNA samples from 19 different partners to cover a diversity determined by sequencing from 5.8% to 16.7%, which corresponds to the expected intrasubtype diversity required for the linkage studies. The results of these studies showed that the technique could be used as a tool for real-time linkage analyses.

To evaluate the use of the technique for epidemiological linkage studies, we tested, by autologous and heterologous HMA, 102 previously characterized HIV-1-positive couples and, in a blinded experiment, compared the results with sequencing. Identical results were obtained in 92/102 cases. Among the 10 cases that generated discrepant results between HMA and sequencing, four of them had a diversity exceeding 5% (5.26–8.58%), which would be expected to generate heteroduplexes, and two others were very close to the threshold (4.42% and 4.12%). The remaining four had heteroduplexes very close to the homoduplexes (relative mobility >90%) and diversities between 2.29% and 3.87%. Thus, the efficiency of the technique to analyze linkage in the case of true epidemiologically linked transmissions is 83.6%, whereas the efficiency of the technique to detect diversity greater than 5% is 90.2%. On the other hand, the efficiency of the technique to detect linked transmissions is 100% since all the transmissions identified as linked by gp41-HMA were confirmed by sequencing. It is interesting to note that 25 individuals among the 204 analyzed by autologous HMA presented profiles that suggest a diversity in the gp41 region of the viral quasispecies that exceeds 5%. Nevertheless, even when heteroduplexes were seen in the autologous HMA of one of the partners, we were able to correctly define linkage in all but two cases. In one case, heteroduplexes were present in the autologous HMA of both partners and the couple was correctly classified as unlinked (Fig. 3B).

Similarly, we prospectively tested 25 samples from newly identified transmission pairs in the PSF cohort in Kigali, Rwanda and 12 similar pairs from the ZEHRP cohort in Lusaka, Zambia. Out of these 37 analyzed cases, only one yielded an HMA profile that resulted in an incorrect classification of the transmission as unlinked, where sequencing results showed that the transmission was linked. Among all the analyzed amplicons, nine of the autologous HMAs showed heteroduplex bands that were similar to those generated by dual infection by two phylogenetically divergent strains.23 After reviewing the population sequences and phylogenetic analyses for these cases, it appeared that this was due to coexisting nonmutated and hypermutated variants within the PCR amplified population,22 although we cannot rule out the possibility that in some cases dual infection by distinct viral variants might have been the source of the heterogeneity.

The presence of heteroduplex bands in the autologous HMAs emphasizes the importance of a thorough analysis of sequences to identify the presence of hypermutation/dual infection for any unlinked transmission and the use of HMA and sequence analyses in parallel for such cases. In our study, the analysis of the HMA profiles of transmission pair Z253, in combination with phylogenetic analyses, prompted us to reconsider the linkage result based on sequence diversity alone. Indeed, this case previously classified as unlinked based on a diversity value of 7.70%, was reclassified as linked since hypermutations were identified in both partners, and the phylogenetic tree showed both sequences branching from a single node with high bootstrap values. From a practical perspective, we now accept linked transmission results determined in the field through gp41 HMA and confirm all unlinked transmission results by sequencing.

The study of coinfections and superinfections is critical in the context of vaccine development. Recent studies showed that superinfection is probably a rare event in subtype B cohorts,27–29 although a recent publication might contradict this initial concept.30 However, this is likely a more common event in cohorts from other subtypes,23,31–33 which constitute the major part of HIV infections around the world. The tool that we developed in this study should also provide a screening mechanism to detect superinfection in couples that are infected with genetically distinct viruses (unlinked couples) who are at risk of superinfection. The RZHRG is currently investigating this both in Zambia and Rwanda.18

In summary, in the context of laboratories in resource-poor settings, the gp41-based HMA allows rapid and inexpensive epidemiological linkage to be established accurately and in real time for transmission pairs.

Acknowledgments

The investigators would like to thank all of the volunteers in Rwanda and Zambia who participated in this study, and all staff members at Projet San Francisco in Kigali and the Zambia Emory HIV Research Project in Lusaka who made this study possible. This study was funded by NIH Grant AI51231 (E.H.) and by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative for site and cohort maintenance (S.A.).

O.M., D.B., E.K., C.A.D., S.A., and E.H. designed the study, analyzed results, and contributed to manuscript preparation. O.M., D.B., E.K., and E.H. contributed to the analysis of results and manuscript preparation. O.M., P.A.H., D.B., N.M., and M.M. were involved in performing the experiments and analyzing the data. O.M., E.K., C.V., K.K., J.M., and S.A. contributed to participant recruitment and follow-up of discordant couple cohorts and seroconverters, field site management, protocol development, and manuscript preparation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Esparza J. The global HIV vaccine enterprise. Int Microbiol. 2005;8(2):93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derdeyn CA. Decker JM. Bibollet-Ruche F, et al. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science. 2004;303(5666):2019–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.1093137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haaland RE. Hawkins PA. Salazar-Gonzalez J, et al. Inflammatory genital infections mitigate a severe genetic bottleneck in heterosexual transmission of subtype A and C HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(1):e1000274. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keele BF. Giorgi EE. Salazar-Gonzalez JF, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(21):7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fideli US. Allen SA. Musonda R, et al. Virologic and immunologic determinants of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(10):901–910. doi: 10.1089/088922201750290023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer W. Perkins S. Theiler J, et al. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat Med. 2007;13(1):100–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeras DI. Hraber PT. Hurlston M, et al. Role of donor genital tract HIV-1 diversity in the transmission bottleneck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(46):E1156–1163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103764108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopera DR. Woodman Z. Mlisana K, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 CTL escape variants provides HLA-mismatched recipients with a survival advantage. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(3):e1000033. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawford H. Lumm W. Leslie A, et al. Evolution of HLA-B*5703 HIV-1 escape mutations in HLA-B*5703-positive individuals and their transmission recipients. J Exp Med. 2009;206(4):909–921. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goepfert PA. Lumm W. Farmer P, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 Gag immune escape mutations is associated with reduced viral load in linked recipients. J Exp Med. 2008;205(5):1009–1017. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salazar-Gonzalez JF. Bailes E. Pham KT, et al. Deciphering human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission and early envelope diversification by single-genome amplification and sequencing. J Virol. 2008;82(8):3952–3970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02660-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen S. Karita E. Chomba E, et al. Promotion of couples' voluntary counselling and testing for HIV through influential networks in two African capital cities. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:349. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen S. Meinzen-Derr J. Kautzman M, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17(5):733–740. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vincenzi I. A longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(6):341–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trask SA. Derdeyn CA. Fideli U, et al. Molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in a heterosexual cohort of discordant couples in Zambia. J Virol. 2002;76(1):397–405. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.397-405.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunkle KL. Stephenson R. Karita E, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: An analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2183–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenna SL. Muyinda GK. Roth D, et al. Rapid HIV testing and counseling for voluntary testing centers in Africa. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl 1):S103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraft CS. Basu D. Hawkins PA, et al. Timing and source of subtype-C HIV-1 superinfection in the newly infected partner of Zambian couples with disparate viruses. Retrovirology 20. 2012;9(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang C. Pieniazek D. Owen SM, et al. Detection of phylogenetically diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 groups M and O from plasma by using highly sensitive and specific generic primers. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(8):2581–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2581-2586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agwale SM. Robbins KE. Odama L, et al. Development of an env gp41-based heteroduplex mobility assay for rapid human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(6):2110–2114. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2110-2114.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upchurch DA. Shankarappa R. Mullins JI. Position and degree of mismatches and the mobility of DNA heteroduplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(12):E69. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vartanian JP. Meyerhans A. Asjo B. Wain-Hobson S. Selection, recombination, and G→A hypermutation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes. J Virol. 1991;65(4):1779–1788. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1779-1788.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manigart O. Courgnaud V. Sanou O, et al. HIV-1 superinfections in a cohort of commercial sex workers in Burkina Faso as assessed by an autologous heteroduplex mobility procedure. AIDS. 2004;18(12):1645–1651. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131333.30548.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyndrickx L. Janssens W. Zekeng L, et al. Simplified strategy for detection of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M isolates by gag/env heteroduplex mobility assay. Study Group on Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. J Virol. 2000;74(1):363–370. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.363-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell RL. Urbanski MM. Burda S. Kinge T. Nyambi PN. High frequency of HIV-1 dual infections among HIV-positive individuals in Cameroon, West Central Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(1):84–92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5a40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell RL. Urbanski MM. Burda S. Nanfack A. Kinge T. Nyambi PN. Utility of the heteroduplex assay (HDA) as a simple and cost-effective tool for the identification of HIV type 1 dual infections in resource-limited settings. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24(1):100–105. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakraborty B. Valer L. De Mendoza C. Soriano V. Quinones-Mateu ME. Failure to detect human immunodeficiency virus type 1 superinfection in 28 HIV-seroconcordant individuals with high risk of reexposure to the virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20(9):1026–1031. doi: 10.1089/aid.2004.20.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Courgnaud V. Seng R. Becquart P, et al. HIV-1 co-infection prevalence in two cohorts of early HIV-1 seroconverters in France. AIDS. 2007;21(8):1055–1056. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32810c8be1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzales MJ. Delwart E. Rhee SY, et al. Lack of detectable human immunodeficiency virus type 1 superinfection during 1072 person-years of observation. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(3):397–405. doi: 10.1086/376534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell MS. Gottlieb GS. Hawes SE, et al. HIV-1 superinfection in the antiretroviral therapy era: Are seroconcordant sexual partners at risk? PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chohan B. Lavreys L. Rainwater SM. Overbaugh J. Evidence for frequent reinfection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 of a different subtype. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10701–10708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10701-10708.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piantadosi A. Chohan B. Chohan V. McClelland RS. Overbaugh J. Chronic HIV-1 infection frequently fails to protect against superinfection. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(11):e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delwart EL. Shpaer EG. Louwagie J, et al. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262(5137):1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]