Abstract

While the effects of sexually explicit media (SEM) on heterosexuals’ sexual intentions and behaviors have been studied, little is known about the consumption and possible influence of SEM among men who have sex with men (MSM). Importantly, conceptual models of how Internet-based SEM influences behavior are lacking. Seventy-nine MSM participated in online focus groups about their SEM viewing preferences and sexual behavior. Twenty-three participants reported recent exposure to a new behavior via SEM. Whether participants modified their sexual intentions and/or engaged in the new behavior depended on three factors: arousal when imagining the behavior, pleasure when attempting the behavior, and trust between sex partners. Based on MSM’s experience, we advance a model of how viewing a new sexual behavior in SEM influences sexual intentions and behaviors. The model includes five paths. Three paths result in the maintenance of sexual intentions and behaviors. One path results in a modification of sexual intentions while maintaining previous sexual behaviors, and one path results in a modification of both sexual intentions and behaviors. With this model, researchers have a framework to test associations between SEM consumption and sexual intentions and behavior, and public health programs have a framework to conceptualize SEM-based HIV/STI prevention programs.

Keywords: sexual behavior, behavior modification, HIV prevention, gay men, sexual intentions

Introduction

North Americans’ use of pornography, or sexually explicit media (SEM), has increased exponentially (Egan, 2000) as advances in Internet and mobile technology have made it extremely accessible, affordable, and anonymous (Cooper, Delmonico, & Burg, 2000). Yet, while exposure has increased, empirical studies on the relationship between SEM consumption and sexual health outcomes have remained sparse for the general population (Stulhofer, Busko, & Landripet, 2010), and especially for men who have sex with men (MSM; Rosser et al., 2012). To better inform researchers and clinicians exploring associations between SEM consumption and sexual intentions and behaviors, a conceptual model that identifies relevant constructs is needed.

SEM Research among MSM Populations

Sexually explicit images are highly acceptable to US MSM (Hooper, Rosser, Horvath, Oakes, & Danilenko, 2008) and SEM is described as “ubiquitous” in the gay male community (Morrison, Morrison, & Bradley, 2007). Producers of gay SEM claim it validates homosexuality, creates an outlet for desire and exploration, and strengthens community (Lucas, 2006). At least one HIV-prevention study has identified SEM as salient in the sexual development of young MSM (Mustanski, Lyons, & Garcia, 2011), and other studies have identified SEM as a major source of information (Kubicek, Beyer, Weiss, Iverson, & Kipke, 2010; Kubicek, Carpineto, McDavitt, Weiss, & Kipke, 2011). Many of the young men in these studies were unaware of the “mechanics” involved in sex between men, particularly anal sex, before seeing the acts in SEM. For them, SEM provided confirmation of sexual attraction and desire. Adult gay men have also suggested the importance of SEM in validating their attraction to men when they were younger (Morrison, 2004).

In a review of the literature, we found four published studies that have attempted to examine the relationship between MSM’s consumption of SEM and their sexual intentions or behaviors. In a study of 66 gay men, Morrison, Morrison, and Bradley (2007) asked study participants about the frequency with which they viewed particular sex acts during a six-month window and their perceived importance of practicing safer sex, for example, knowing a person’s sexual history and using a condom with casual sex partners. They found no association between SEM exposure and the importance of safer sex. In a study that included 71 men, 19 of whom identified as gay or bisexual, Weinberg, Williams, Kleiner, and Irizarry (2010) asked their study participants about their frequency of SEM consumption and sexual behavior during a 12-month window. Weinberg et al. found little evidence to suggest an association between SEM use and anal or oral sex. Though neither study found an association between consumption and sexual intentions or behaviors or reported a significant effect, it is possible that the small sample sizes lacked sufficient power to detect differences. Stein, Silvera, Hagerty, and Marmor (2011) published results from a cross-sectional survey study of 751 MSM living in the U.S. They found a positive correlation between viewing bareback SEM (actors engaging in anal sex without condoms) and having anal sex without condoms. Recently, Traeen & Daneback (in press) published results from a study investigating the consumption of SEM and sexual behavior among a sample of 2,381 Norwegians of various sexual identities. They concluded that there was evidence of an association between use of SEM during partner sex and sexual risk behavior among gay or bisexual Norwegian men. Because studies of the effects of SEM consumption on sexual intentions and behaviors among MSM are limited, the topic warrants further study.

Conceptualizing Effects of SEM Consumption on Sexual Intentions and Behaviors

While we recognize cumulative exposure to SEM likely affects intentions and behaviors, for this study we were interested in the influence of exposure to new sexual behaviors via SEM. Fisher and Barak (2001) provided a theoretical framework for our study since they applied the sexual behavior sequence model (Byrne, 1977) to SEM consumption. The sexual behavior sequence posits an operant conditioning process where an unconditional sexual stimulus leads to sexual arousal (influencing internal factors such as affect, cognition, imagination, evaluation, expectations) which produces overt sexual behavior, and via operant reward and/or punishment effects, the stimulus becomes conditioned (Byrne, 1977). As applied to Internet SEM, Fisher and Barak (2001) propose that antecedents to viewing SEM include an individual’s lifetime learning history, intentions about and emotional responses to sexuality, and expectations about potential sexual outcomes. Fisher and Barak (2001) suggest that an individual’s decision to view SEM is a function of his/her arousal and affective and cognitive responses to sexuality. For example, an individual with high arousal and positive affective and cognitive responses to SEM scenarios would be more likely to act out a new scene, than an individual with lower arousal and negative affective and cognitive responses to SEM scenes.

The strength of applying the Bryne’s (1977) sexual behavior sequence to Internet SEM is that it has a strong theoretical base in operant conditioning and it is intuitive. The weakness is that it is hypothetical, and hence, has low ecologic validity. In addition, Fisher and Barak (2001) were primarily interested in conceptualizing the effects of Internet SEM on problematic use, especially in regulating SEM consumption and also in examining the antisocial effects of degrading and/or violent heterosexual SEM. We reasoned that what SEM MSM prefer and its effects on their lives is likely to be very different than heterosexuals, and hence sought to develop a more ecologically valid model based in MSM’s actual experience with Internet SEM. We hypothesized that MSM might be more willing to engage in sexual behaviors learned about while watching SEM when they found the behaviors to be arousing and pleasurable, and when they identified trusted sex partners willing to engage in these behaviors. As HIV prevention researchers, we were particularly interested in examining, what effect, if any, viewing SEM depicting safer sex or unprotected anal sex, had on safer sex intentions and sexual risk behavior. We believe this interest to be also relevant to sex and relationship therapists working with couples where SEM viewing behavior and/or sexual risk behavior might be presenting concerns.

Method

The Sexually Explicit Media (SEM) study is a NIH-funded study examining if and how MSM’s use of SEM influences sexual risk behavior. For the purposes of this study, SEM was defined as “any kind of material aimed at creating or enhancing sexual feeling or thoughts in the viewer, and containing explicit exposure and/or depictions of the genitals as well as clear and explicit sexual acts (e.g., vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, oral sex, masturbation, bondage, etc.)” (Hald & Malamuth, 2008). Participants were recruited online over a two-week period in January 2010 using banner advertisements on 148 websites affiliated with the Gay Ad Network (Quantcast Corporation, n.d.). Banner advertisements directed interested persons to a webpage hosted on a dedicated university server with appropriate encryption to ensure data security. The webpage included information about the study procedures and a link to the eligibility screener. From 448,472 banner impressions, there were 1410 clicks, a click through rate of 0.3%. From these, 227 men met the eligibility criteria of being a male age 18 years or older, having had sex with another man in the 90 days prior to study enrollment, living in the US and its territories, and, on average, having viewed SEM at least weekly. To limit the size of focus groups, invitations were sent out in blocks based on the order in which the men who had screened eligible expressed interest. Of the eligible men, 139 were invited to participate in the study. Of the 139 who received an invitation, 79 (57%) were available to meet at the schedule time, consented to participate in an online synchronous focus group, and logged in at the time of their scheduled focus group. No one dropped out of a focus group after logging into the system. After each synchronous focus group, participants were invited to participate in a follow-up asynchronous focus group (message board) and 66 (84%) participants posted additional responses in this format. Overall, we conducted 13 focus groups from mid-January to mid-March 2010.

Procedures

After they consented to be in the study, we asked participants if they preferred watching SEM in which the models used condoms for anal sex (termed “safer sex SEM”) or not (termed “bareback SEM”). We then asked participants two questions aimed at determining if their SEM use might be problematic from their point of view. The questions were: “Has your use of porn ever caused you to feel distress? (yes/no/unsure/refuse to answer)” and “Has your porn use ever gotten in the way of doing things socially, at work, or in another important area of your life? (yes/no/unsure/refuse to answer)”. Those questions were developed to be consistent with the identification of symptoms of distress and problematic behaviors in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Based on what type of SEM men reported viewing and their responses to the questions about problematic SEM use, participants were assigned to one of four categories: non-problematic bareback SEM consumers, problematic bareback SEM consumers, non-problematic safer sex SEM consumers, or problematic safer sex SEM consumers. We conducted three online synchronous focus groups within each category, with the exception of the non-problematic bareback category, for which we conducted four focus groups to compensate for low attendance in one of the groups.

Each focus group lasted approximately 90 minutes. To promote genuine answers to socially sensitive items, participants remained anonymous to each other using self-created user IDs instead of names, and all communication was by chat using Adobe Connect Pro (Adobe Systems Incorporated, 2009). Within 24 hours from the conclusion of the synchronous focus group, participants were invited to respond to follow-up questions about issues raised during their synchronous group discussion through postings to the asynchronous message board. Participants had 48 hours to respond to questions and comments posted on the message board. Participants were compensated $50 for participating in the synchronous focus group and an additional $5 for participating in the asynchronous focus group.

Measures

Three members of the research team facilitated each synchronous focus group using a semi-structured moderator guide focused on SEM consumption, preferences, viewing habits, and sexual behaviors. At the beginning of each focus group, participants were asked to respond to polling questions about the type of SEM they watched, the locations where they watched it, and the devices they used to watch it. This information was graphed and shared with participants during the focus groups in order to generate discussion about differences in participants’ reported consumption pattern and what they perceived to be a typical consumption pattern for MSM. Questions varied in order and wording, due to differences in the conversational flow of each focus group, examples of typical questions were as follows: “How has the type of porn you watch changed over time?” “When are you more (or less) likely to watch porn?” “What have you learned from watching porn?” And, “what have you tried to do sexually with others after you saw it in porn?” After each synchronous focus group, the research team reviewed the transcript and identified up to five follow-up questions, which were used to generate discussion during the asynchronous focus group. Follow-up questions were designed to clarify situations in which participants watched SEM, to determine the advantages and disadvantages of watching SEM, and to determine if, when, and how, they decided to act out a sexual scene first observed in SEM.

Data Analysis

Focus group transcripts were analyzed using NVivo 8 (QSR International, 2010). During analysis, we engaged in an iterative coding process, moving from open codes, to concepts, and ultimately, to macro-level themes. As new codes, concepts, or themes arose, the two researchers responsible for coding the data agreed on definitions for each. During axial coding, we found Fisher and Barak’s (2001) ideas about the influence of arousal and pleasure a useful framework for data interpretation. The research team validated study findings by seeking alternative explanations and by conducting two peer debriefings (Denzin & Lincoln, 2003) with researchers experienced in studying SEM or sexual risk-taking.

Presentation of Results and Model Conceptualization

Participant Characteristics and SEM Consumption

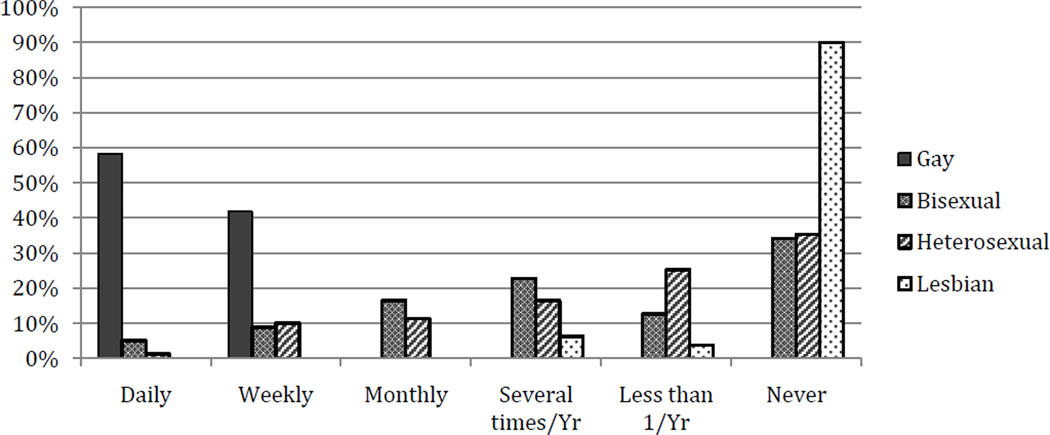

As detailed in Table 1, the typical participant identified himself as being less than 45 years of age, white, gay, and HIV-negative. A priori, classification of participants by SEM preferences and problematic versus non-problematic use was an attempt to identify between-group differences. However, no meaningful differences were found between groups in described consumption pattern, reasons for consumption, or sexual intentions and behaviors. Therefore, the 79 participants were treated as one class. All participants were required to watch SEM at least weekly to meet eligibility requirements for the study. They all reported watching gay SEM daily to weekly; in addition, 14% reported consuming bisexual SEM, and 10% reported consuming heterosexual SEM at least weekly (Figure 1). We asked participants to estimate the percentage of safer sex and bareback SEM they watched 30-days prior to participating in the synchronous focus group. While most participants (81%) reported watching both safer sex and bareback SEM, 11% reported only watching safer sex SEM, and 8% reported only watching bareback SEM.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N=79)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 33 | 41.8% |

| 25–44 | 34 | 43.0% |

| 45+ | 12 | 15.2% |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 7 | 8.9% |

| Black | 6 | 7.6% |

| White | 59 | 74.7% |

| Other | 7 | 8.9% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 9 | 11.4% |

| Non-Hispanic | 70 | 88.6% |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Gay | 65 | 82.3% |

| Bisexual | 8 | 10.1% |

| Queer | 3 | 3.8% |

| Not sure | 3 | 3.8% |

| HIV Status | ||

| HIV+ | 9 | 11.4% |

| HIV− | 55 | 69.6% |

| HIV unsure | 14 | 17.7% |

| Refuse to answer | 1 | 1.3% |

Figure 1.

Frequency of SEM consumption by genre.

Accessing SEM for Consumption

A priori, we hypothesized that those men who preferred bareback sex would prefer depictions of barebacking, while those men who preferred to engage in safer sex would prefer depictions of condom use. The data did not support this hypothesis. Instead, cost appeared to be the most important factor determining viewing choices. The majority (72%) did not pay for SEM; 19% paid $1-$24 per month, 2% paid $25-$49 per month, and 6% paid more than $50 per month. Choosing not to pay for SEM frequently limited participants’ viewing options to amateur websites, where models were perceived to be less attractive, and where bareback sex was more common than on paid websites. Participants judged the attractiveness of the models to be the second most important factor in determining viewing choices, rather than the actors’ condom use:

It’s not about the safe or bareback aspect of it. It’s about who is on camera, if I’m turned on by the guys. (Participant 34)

It’s [bareback porn] not a deciding factor for me. It’s an added bonus if I’m watching it and they don’t use one [a condom]. (Participant 3)

If actors were equally attractive, most participants – regardless of whether they preferred to engage in bareback or safer sex – said they preferred watching a bareback clip more than a safer sex clip.

Few participants’ viewing preferences paralleled their sexual behavior. When viewing practices and sexual behavior were aligned, it was because men who use condoms wanted to support studios that promoted safer sex messages. For example, one participant wrote, “I am an advocate of safer sex and thus want to reward those porn makers that use condoms” (Participant 69).

Antecedents to SEM Consumption

An assumption in our analysis was that each viewing episode created an opportunity to maintain or modify existing sexual intentions and behaviors. Identifying antecedents to SEM consumption is important to understand an individual’s frequency of viewing. Data suggest that the cultural scenario is a critical antecedent to SEM consumption. Participants described a cultural scenario in which SEM consumption was normative within the gay and bisexual male community. One participant wrote, “Porn is a part of the community. I don't think it’s looked at negatively or positively, just that it is” (Participant 7). Some attributed celebrity status to SEM actors. Others, while recognizing the historic status of porn stars in the US gay and bisexual male community, suggested that their influence was waning as an increasing number of MSM accessed amateur SEM more frequently than professionally-produced SEM. “The trend seems to be going to amateur… porn stars are losing their stardom” (Participant 8), wrote one participant. While frequent SEM consumption was described as normative, no participant indicated that there was a cultural expectation to support the SEM production studios or their actors. In fact, when asked from which websites they used to access SEM, participants were more likely to identify amateur than studio websites.

Additional factors influencing the frequency of SEM consumption included Internet access, illness, and time constraints. Participants reported being more likely to consume SEM when they had Internet access, were physically healthy, and did not have a busy schedule. Having sexual partners was identified as an additional factor that modified SEM consumption; SEM frequently satisfied a desire for sex in the absence of available trusted sex partners. For example, one participant wrote, “I love it when I have a wild boyfriend, but using porn is a substitute for that” (Participant 54). Participants described different motivations for watching SEM when alone as compared to with a partner. For instance, one participate wrote, “Watching it alone is just to pass the time, please myself, and release stress” (Participant 48).

Stress, anger, loneliness, and boredom were mood states participants identified as influencing the frequency and type of SEM they consumed. Often, SEM consumption occurred while masturbating. Consuming SEM and masturbating was mentioned as a common outlet for reducing stress, anger, loneliness or boredom. One participant wrote, “Good mood = gentle porn. Bad mood/stressed = more rough/testosterone porn… I’ve noticed that when I’m in a bad mood, if I rub one (or two or four) out [masturbate] that I am much calmer and less angry” (Participant 53). Other participants wrote similar statements. Thus, SEM consumption appeared to increase during periods of stress, anger, loneliness and boredom. Two participants suggested that SEM consumption decreased when depressed and one participant noted that he used his SEM consumption pattern as a barometer for his mood state: “I have a real problem with depression, so if I lose the ability to enjoy visual stimuation, I know something’s really wrong” (Participant 16).

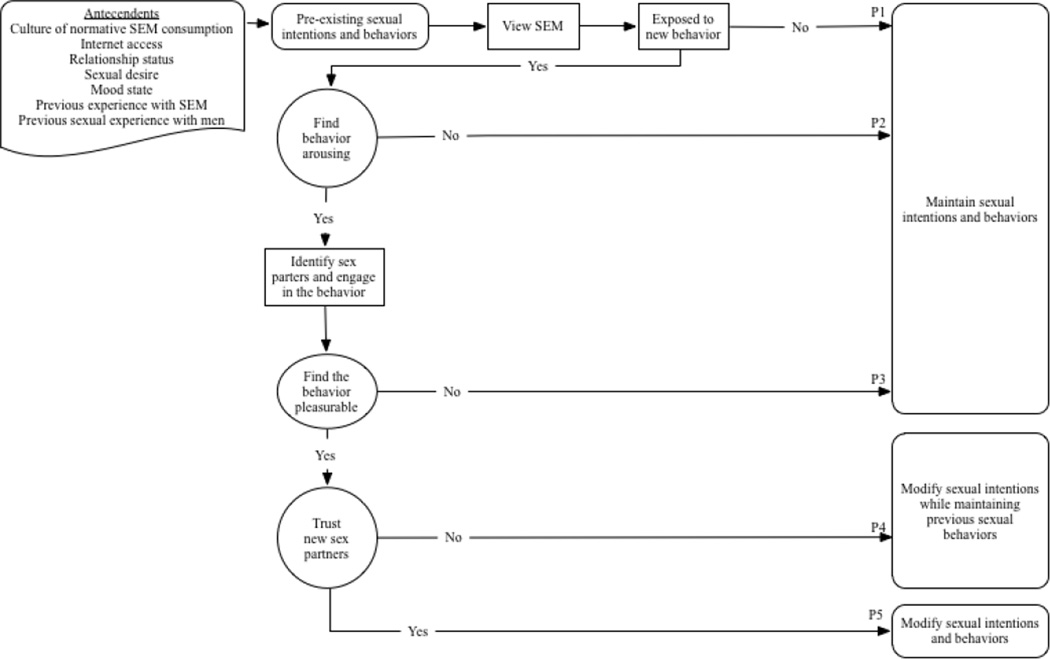

Pathways between Exposure to Gay SEM and Sexual Intentions and Behaviors

Figure 2 is our model of the influence of viewing SEM on sexual intentions and behaviors. The model begins by identifying antecedents to SEM consumption; it assumes these antecedents influenced sexual intentions and behaviors before exposure to a new sexual behavior via SEM. The model proposes five pathways between exposure to a sexual behavior via SEM and the maintenance or modification of sexual intentions and behaviors. Three pathways allowed for the maintenance of sexual intentions and behaviors. One pathway allowed for the modification of sexual intentions and the maintenance of sexual behaviors, and one pathway allowed for the modification of both sexual intentions and behaviors. We used circles to represent intrapsychic processes and rectangles to represent actions.

Figure 2.

The SEM Risk Behavior (SBR) Model is a conceptual model of how each exposure to a new sexual behavior via SEM influences the sexual intentions and behaviors of MSM. The circles represent an intrapsychic process and the rectangles represent an action. P1=pathway 1, P2=pathway 2, etc.

Pathway 1: Maintenance of sexual intentions and behaviors due to no new exposure

The dominant path in our model, which is illustrated from left to right at the top of Figure 2, resulted in the maintenance of sexual intentions and no change in sexual behavior. The 56 individuals in this path reported no recent exposure to SEM that included a new sexual behavior. Rather, their SEM use reflected, and likely reinforced, their current sexual behavior and interests. Because these participants had no recent exposure to new sexual behaviors via SEM, their descriptions of SEM were part of normative scripts that occurred with little thought or dissonance about what they were consuming. These participants reported when watching SEM, they fantasized about interacting with the actors as voyeurs or participants in the scene. Fantasy allowed participants to be aroused and experience pleasure while avoiding situations they perceived as risky, including to avoid engaging in behaviors that might place them at risk of HIV infection or transmission:

One of the reasons I watch porn is to see things I would never do in real life. (Participant 49)

Part of porn is that it lets you partake in things that aren’t safe. (Participant 4)

I want to bareback yet know the consequences, so I live vicariously through bareback porn… I watch bareback porn because I want to bareback. (Participant 51)

When asked about their desire to engage in a behavior they might see in SEM, these participants reported having no sex partners with whom they were willing to act out the scene. Thus, after consuming SEM, these participants maintained their sexual intentions and behaviors.

Pathway 2: Maintenance of sexual intentions and behaviors due to a lack of arousal

Thirteen participants described viewing a novel SEM clip that did not result in arousal. These situations occurred when watching behaviors, especially fisting (i.e., brachioproctic insertion), that they considered extreme:

Fisting is interesting, I don’t know about appealing. (Participant 8)

I was sick to my stomach when I saw fisting for the first time. (Participant 78)

Kinky stuff like fisting, stuff involving blood, or other “extreme” stuff I just can’t watch. (Participant 46)

When exposed to a new behavior via a SEM scene, these participants reported not finding the behavior arousing, seeking out sex partners, or fantasizing about the behavior. Instead, their existing sexual intentions and behaviors were maintained.

Pathway 3: Maintenance of sexual intentions and behaviors due to engaging in a new behavior that was not pleasurable

One participant described a situation that resulted in the maintenance of previously held sexual intentions and behaviors after acting out a SEM scene with sex partners:

We tried double penetration… we [got] drunk one night and tried watersports, but I became really sick… Alcohol plays a lot into what I have done that is considered crazy. (Participant 20)

The participant reported not finding double penetration or watersports pleasurable, so he did not incorporate the behaviors into his normative script. Instead, the participant rationalized these behaviors as “crazy” and attributed his participation to consuming too much alcohol.

Pathway 4: Modifying sexual intentions while maintaining sexual behaviors due to a lack of partner trust

Three participants described a situation in which they did not identify trusted sex partners with which to repeatedly engage in a behavior, resulting in the modification of sexual intentions and the maintenance of current sexual behavior:

I tried a hardcore leather scene once after watching it in a bareback porn. I let the guy tie me up and then do whatever he wanted to me. It was a HELLUVA risk because he was just a random fling and could have done any number of harmful things to me. He didn't and he came on me, not in me, but we DID bb [bareback sex], and afterwards I wondered, “why in the world did I let that happen, that was stupid thing to do.” I did it mid-afternoon, and I WOULD do it again, but only with a trusted partner who's [HIV] status I knew. (Participant 45)

There's been several pornos in which there are random hookups and unprotected sex with people who just met at a party and are rather drunk. When I watched those I wondered what it'd be like. So, I gave it a try. [I] got completely drunk and got this other guy completely drunk too. We ended up having unprotected sex. At first I was reluctant to make out with him, but I kept telling myself that this was the way to try what I had seen in those porn clips. We had bb [bareback sex] and I never saw him again. This took place at night and it was just thrilling for me at that moment. However, the next day I was shocked and surprised I did something like that. I was so worried about the different diseases that could have been transmitted to me by this random guy. Thank God he didn't have anything. (Participant 48)

I had gone to a bathhouse sometime after watching a glory hole movie. The bathhouse was really just a hookup joint with stalls made just for the glory hole. I went in one and gave oral to a man I couldn’t even see. If I had not watched the movie, I probably wouldn’t have ever done it. I’ve never done it since. Afterwards, I really didn’t feel any different then [when] I have after other trysts, but I went to get tested next day and again three months later just to make sure. (Participant 44)

All three participants tried a new risky sexual behavior with persons whom they did not know, and with whom they had little trust. Though all report finding the behaviors in which they engaged pleasurable, they identify the absence of trusted sex partner whose HIV/STI status was known to them, as their main reasons not to repeat the behavior.

Pathway 5: Modification of sexual intentions and behaviors

After acting out a scene they first saw in SEM, 19 participants reported modifying both their sexual intentions and their sexual behaviors. Seven participants reported deep throating (oral sex), seven reported rimming another man (analingus), three reported hooking up and having sex with casual partners (they did not specify the behaviors in which they participated), and two reported barebacking. All 19 found engaging in the behavior pleasurable and indicated they would do it again. The following quote was typical of participants following this pathway: “I have used porn to demonstrate a particular position that I really wanted to try with my partner” (Participant 44). For participants on this pathway, the decision to act out the scene was a consensual one made between them and sex partners they trusted enough to avoid feelings of regret. Usually, the sexual partners were boyfriends or regular sex partners. Comments from these participants indicated they would engage in the behaviors again because they found them to be arousing and pleasurable, and because they were able to identify a trusted sex partner.

Discussion

Based on our findings, we advance the SEM Risk Behavior (SRB) model as a new conceptual model of how exposure to new sexual behaviors via SEM influences sexual intentions and behaviors (Figure 2). Similar to Fisher and Barak’s adaptation of Byrne’s sexual behavior sequence model, arousal and pleasure are central to explaining whether new sexual behaviors viewed in SEM result in changed behavior. We highlight three advantages of the SRB model over the prior model. First, it is grounded in MSM’s actual experience and SEM consumption. As such, it has greater ecologic validity than the prior model that was theoretical in origin. Second, it is focused on HIV risk, which remains the greatest sexual health concern for this population. For clinicians and HIV prevention professionals, this obviates the concern whether the theoretical model is applicable to unsafe sex. Third, it identifies a relational component – trusted sexual partner – as central to MSM’s decision whether or not to enact the behavior, whereas the sexual behavior sequence only considers intra-individual components.

The current study advances the literature examining what relationship, if any, exists between SEM consumption and HIV risk behavior in MSM. In the two published studies assessing SEM use and HIV risk for MSM, Morrison et al., (2007) found no association, while Stein et al., (2011) found a clear association. Using a qualitative rather than a quantitative approach, this study found evidence that both can be true, and likely dependent on three critical variables: arousal, pleasure, and partner trust.

Whether MSM adopt a new behavior viewed in SEM depends on whether they find the behavior arousing and pleasurable, and whether they have a trusted sex partner with whom to enact the behavior. Four participants report barebacking after seeing it in SEM, one reported double penetration (whether condoms were used is unclear), and three reported hooking up (specific sex acts were unspecified). Three participants modified their intentions while reverting back to their previous behavior after experiencing negative effects from watching and enacting a scene first viewed in SEM. One of the three articulated a plan to minimize the likelihood of experiencing perceived negative consequences when engaging in the behavior again—planning to postpone engaging in the behavior until he identified trusted sex partners. Our data suggest that MSM are more likely to engage in risk behaviors they learn about while watching SEM when the new behavior is arousing and pleasurable, and when trusted sex partners are also willing to engage in the behavior.

Our data suggest that many MSM watching bareback or risky sexual scenarios fantasize about acting out the scenes. Participants decided not to act out riskier scenes because of potential negative consequences. If our data are transferable to other MSM, then for many, if not most MSM, consuming SEM provides an outlet for unsafe sexual desires or intentions, while avoiding the risk associated with engaging in unsafe sexual behavior. This mirrors research conducted byWeinberg et al. (2010) on college students’ SEM consumption where they found no association between SEM consumption and the number of sexual partners. Future research should measure the strength of a possible association between overall SEM consumption and the reduction of risk behavior, and be specific in examining the effects of bareback SEM consumption and sexual intentions and behavior.

The exploratory nature of this study has several limitations. First, our sample was comprised mostly of young, white, gay- or bisexual-identified, HIV-negative men living in the US. Future research is needed to identify whether MSM with different characteristics experience and use SEM differently, and whether the model is specific to MSM or transferable to other populations. Second, while some pathways in the SRB model were based on comments from numerous participants, other pathways were based on sparse data. The lack of data saturation on some pathways limits the strength of our findings. Third, while having trusted sex partners emerged as a major theme, an in-depth exploration of the construct was beyond the scope of this study. Future research should explore how MSM identify and define “trusted” sex partners or situations that facilitate or limit trust between persons, and the implications of trust on the intention to have protected or unprotected sex with others. Fourth, data were collected using online synchronous and asynchronous focus groups. This method of data collection had the advantages of bringing together MSM from across the US while protecting the identities of participants from each other. For some participants, the ability to talk about their SEM consumption and sexual behavior without revealing their identity to other participants might have increased their comfort and willingness to share highly personal experiences in the focus group. In addition, this method allowed participants to easily view and discuss websites, images, and video clips, and yielded transcripts ready for immediate analysis. However, a limitation of this method is that responses to our questions might have been briefer than we could have obtained in face-to-face focus groups. Fifth, based on a description of participant’s experiences with SEM, we have proposed a model that includes linear relationships. However, data were not collected over time. Longitudinal quantitative and qualitative studies are needed to validate and to determine the strength of the proposed relationships.

Against expectations, we did not find differences between non-problematic bareback SEM consumers, problematic bareback SEM consumers, non-problematic safer sex SEM consumers, and problematic safer sex SEM consumers. Lack of differences could indicate MSM experience SEM similarly, and that few have a significant problem with SEM consumption. Alternatively, though we attempted to identify and recruit both non-problematic and problematic users, the questions used to screen for problematic use might have lacked specificity. If we had time-delimited our questions to those currently experiencing problems, rather than asking if participants had ever experienced problems, we might have been able to improve our differentiation of problematic and non-problematic SEM users. Future research should explore the extent to which SEM use is problematic for MSM, identify constructs of problematic SEM use, and develop measures for identifying problematic SEM users.

Also against expectations, most participants did not consider SEM depicting bareback or safer sex to be the most important consideration in choosing what SEM to view. Rather, they identified cost and actor attractiveness as more important considerations than use of condoms. Since participants report that a preference for free SEM increases the likelihood of viewing amateur SEM, and since amateur SEM is more likely to depict bareback SEM, this preference has implications for HIV prevention. Future research should examine what it is about cost that is primary to MSM’s decision-making. Is it as simple as participants not wanting to pay; is it because accessing free SEM is faster; or does it, for example, reflect concerns about maintaining anonymity and distrust of online memberships in paid SEM sites?

The SRB model offers clinicians a tool to conceptualize how clients’ SEM viewing habits might affect their sexual intentions and behaviors. The SRB model also provides a framework to guide further studies of the associations between SEM consumption and sexual intentions and behaviors. For most MSM, exposure appears to modify sexual intentions and/or behaviors if the response to the exposure was both arousing and pleasurable, and if willing, trusted sex partners were accessible. Future research should explore the effect of cumulative SEM exposure on sexual intentions and behaviors. A study of cumulative exposure would allow for the testing and expansion of our model to offer a more inclusive depiction of SEM consumption’s influence on sexual intentions and behaviors. If our model is found to be robust and the proposed pathways are found to depict causal relationships between SEM consumption and sexual intentions and behaviors, the model creates new opportunities for sexual health education, sex therapy, and HIV/STI prevention.

Acknowledgments

The Sexually Explicit Media (SEM) study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS, grant number R01MH087231. All research was carried out with the approval of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, study number 0906S68801.

References

- Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe Acrobat Connect Pro (Version 7.5) San Jose, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. IV-text revision ed. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D. Social psychology and the study of sexual behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1977;3:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A, Delmonico D, Burg R. Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2000;7(1):5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Strategies of qualitative inquiry. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Egan T. Erotica, Inc.: Technology sent Wall Street into market for pornography. New York Times, Oct, 23. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Barak A. Internet pornography: a social psychological perspective on internet sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(4):312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hald GM, Malamuth NM. Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(4):614–625. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper S, Rosser BR, Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Danilenko G. An online needs assessment of a virtual community: what men who use the internet to seek sex with men want in Internet-based HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(6):867–875. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9373-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, Iverson E, Kipke MD. In the dark: young men's stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Education and Behavior. 2010;37(2):243–263. doi: 10.1177/1090198109339993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Carpineto J, McDavitt B, Weiss G, Kipke MD. Use and perceptions of the internet for sexual information and partners: a study of young men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):803–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9666-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M. On Gay Porn. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 2006;18:299. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison T. "He was treating me like trash, and I was loving it..": perspectives in gay male pornography. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47(3–4):167–183. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison T, Morrison M, Bradley B. Correlates of gay men's self-reported exposure to pornography. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2007;19(2):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Lyons T, Garcia SC. Internet use and sexual health of young men who have sex with men: a mixed-methods study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(2):289–300. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9596-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo (Version 9) Cambridge, MA: QSR International; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Quantcast Corporation. (n.d., 2010) Gay Ad Network. Retrieved September 23, 2010, from http://www.quantcast.com.

- Rosser BR, Grey JA, Wilkerson JM, Iantaffi A, Brady SS, Smolenski DJ, et al. A commentary on the role of sexually explicit media (SEM) in the transmission and prevention of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) AIDS and Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Silvera R, Hagerty R, Marmor M. Viewing pornography depicting unprotected anal intercourse: Are there implications for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9789-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulhofer A, Busko V, Landripet I. Pornography, sexual socialization, and satisfaction among young men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(1):168–178. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traeen B, Daneback K. The use of pornography and sexual behaviour among Norwegian men and women of differing sexual orientation. Sexologies. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MS, Williams CJ, Kleiner S, Irizarry Y. Pornography, normalization, and empowerment. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]