Abstract

The immobilization of membrane-bound molecules on organic-inorganic cholesteryl-succinyl silane (CSS) nanofibers is investigated. Fluorescent microscopy and a cell capture assay confirm the stable and functional immobilization of membrane-bound antibodies and imaging agents on the electrospun CSS nanofibers. An insert-and-tighten mechanism is proposed for the observed hydration-induced reduction in lipid nanofiber diameter, the immobilization of membrane-bound molecules, and the improved efficiency of cell capture by the functionalized CSS nanofibers over their film counterparts. The ability to stably and functionally immobilize membrane-bound molecules on the CSS nanofibers presents a promising method to functionalize lipid-based nanomaterials.

Functionalizing micro/nanostructured materials for bio-recognition and manipulation may have important applications in a wide range of biomedical areas. Of particular interest to cancer patients, physicians, and researchers is the isolation and numeration of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which has diagnostic and prognostic significance in many types of metastatic carcinomas.1 Since CTCs express cellular receptors that are absent in normal hematologic cells, ligand-receptor interactions are often explored as a mechanism for probing and selectively capturing CTCs from the peripheral blood of cancer patients.2 However, the low abundance of CTCs (i.e., as few as one cell per 106 or 107 leukocytes3) imposes highly demanding criteria on the design and development of a cell capture device. It has been proposed to build microstructured2 or nanostructured probes4 in a device to enhance the cell-probe interactions at the whole-cell and/or subcellular levels with the goal of improving the sensitivity of cell capture. Recently, the potential of functionalized electrospun nanofibers as probes for cell capture has been investigated.5, 6 Often ligands such as antibodies (Abs)2, 4, 6 and aptamers7 that specifically target the cellular receptors of CTCs are chemically conjugated to the micro-/nanostructured probes in a multi-step procedure. Previously, we reported that electrospun organic-inorganic lipid nanofibers are capable of functionally immobilizing Abs and capturing targeted cells without any chemical treatment.5 In this study, we examine the underlying mechanism of Ab immobilization on the electrospun lipid nanofibers and illustrate the nanotopographic effects of the lipid nanofibers on cell capture.

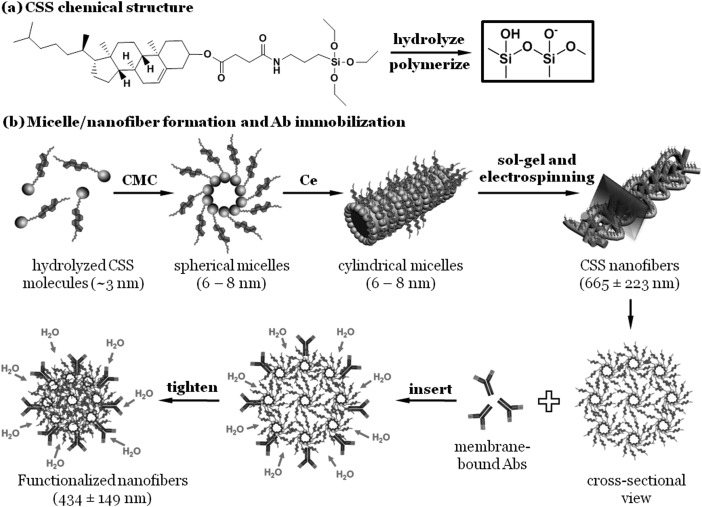

Following an organic-inorganic hybridization strategy, polymerizable CSS consisting of a triethoxysilyl head, a steroid tail, and an amide link was synthesized [Fig. 1a], as reported in our previous studies.5, 8 The CSS powders were dissolved in a mixture of 1 ml tetrahydrofuran (THF) and 10 μl 37% hydrochloric acid (HCl). Due to the existence of a small amount of water in the mixed solvent, the CSS molecules were hydrolyzed and partially polymerized after 8 h of incubation. In a fashion similar to the micelle formation of lecithin in mixed isooctane and water,9 the resulting amphiphilic lipids self-assembled into various micellar structures. When the CSS concentration (C) was lower than the entanglement concentration (Ce) but higher than the critical micelle concentration (CMC), spherical micelles were formed. When C > Ce, cylindrical micelles were self-assembled, the core was comprised of the negatively charged triethoxysilyl heads of the hydrolyzed CSS molecules and the hydrogen-bond forming amide links, while the steroid tails formed the solvent-swollen corona [Fig. 1b]. As proposed by McKee et al.,10 the formation of entangled cylindrical micelles is critical to the electrospinning of lipid fibers. Specifically, a lipid concentration of 2–2.5 Ce is required for the electrospinning of uniform fibers. Using a custom-built device,11 bead-free nanofibers were electrospun from 69% w/w CSS solutions at a voltage of 9 kV, a spinneret-to-collector distance of 12 cm, and a feeding rate of 167 μl/h. The CSS nanofibers were formed via a combined sol-gel and electrospinning mechanism.5

Figure 1.

A proposed model for fiber formation and antibody immobilization. (a) CSS chemical structure. (b) A schematic representation of spherical micelle, cylindrical micelle, and nanofiber formation, and an insert-and-tighten mechanism for the stable and functional immobilization of membrane-bound molecules such as antibodies.

As illustrated in Fig. 1b, the CSS nanofibers are composed of multiple layers of entangled cylindrical micelles. When immersed in aqueous solution, the highly hydrophobic steroid tails of the CSS nanofibers are exposed to water. To reduce their energetically unfavorable contact with water molecules, the CSS nanofibers attempt to shrink in all the dimensions. However, the ultra-length of the nanofibers imposes a spatial constraint on any shrinkage in the fiber direction. As a result, the CSS nanofibers only shrink in the diameter direction. Consequently, the hydration-induced reduction in fiber diameter provides a unique insert-and-tighten mechanism for the functional immobilization of molecules such as Abs. Specifically, when the CSS nanofibers are immersed in an aqueous solution of membrane-bound molecules, the membrane-anchoring regions of the molecules will be inserted into the CSS layers. Recent studies suggest that both hydrophobic amino acids and alkyl chains can be inserted into the lipid membranes,12 and that the raftlike domains rich in cholesterol enhance the stability of the inserted membrane-anchored proteins.13 Further, the insertion of hydrophobic membrane-anchoring domains is facilitated by the bending-induced lipid-packing defects in the lipid membranes.12 In this study, the CSS cylindrical micelles comprising the lipid nanofibers are expected to create such lipid-packing defects for the insertion of the transmembrane regions of the membrane-bound molecules. Upon water immersion, the CSS nanofibers shrink in the diameter direction, tightening the inserted molecules.

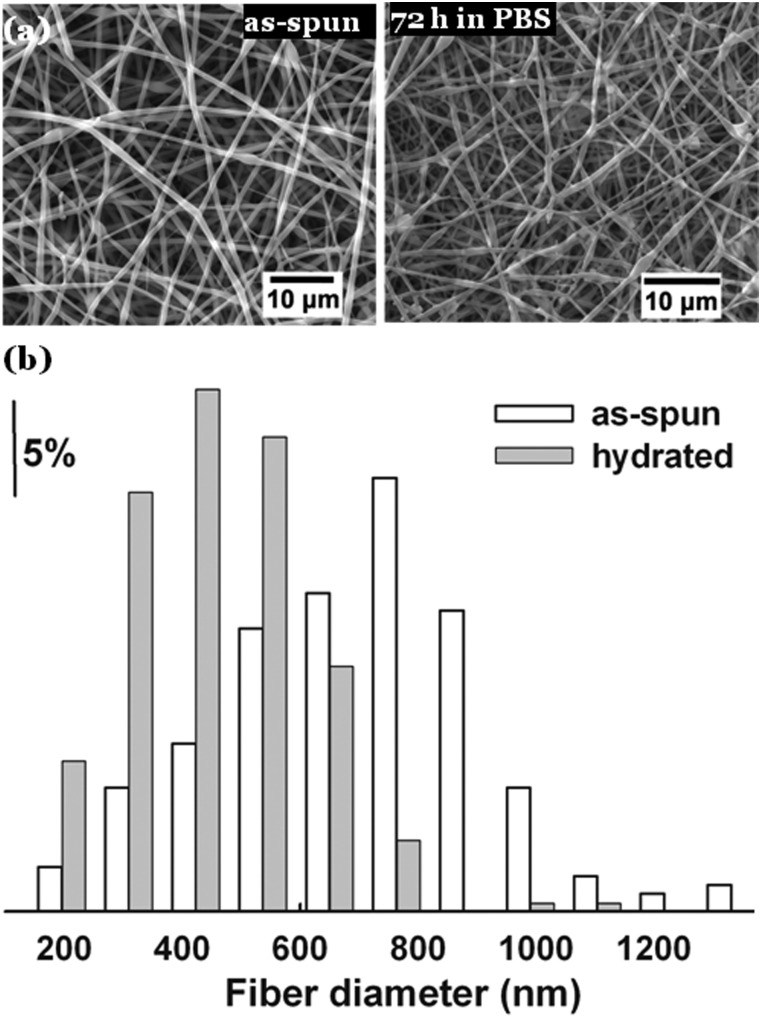

To examine the hydration-induced diameter reduction of the CSS nanofibers, the as-spun fibers and the fibers that were hydrated in 1x phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 72 h were viewed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The obtained SEM images were analyzed using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed imagej software to determine the Feret's diameters of the nanofibers. The fiber morphologies and diameter distributions of the as-spun and hydrated CSS nanofibers are presented in Figs. 2a, 2b, respectively. The SEM analysis revealed the formation of nearly bead-free CSS nanofibers and the enhanced stability of CSS nanofibers in PBS over their phospholipid counterparts, which display insufficient morphological stability in water.10 A quantitative analysis of fiber diameter distributions suggests that the electrospinning of CSS solutions produced fibers of 665 ± 223 nm in diameter. The wide range of fiber diameter distribution was likely due to the emanation of lateral branches from an unstable CSS solution jet in the electrospinning process and the subsequent formation of secondary fibers, as suggested by Yarin et al. for fiber bifurcation in the electrospinning of polymer solutions.14 After being hydrated for 72 h, the CSS fibers decreased to 434 ± 149 nm in size, indicating a 35% reduction in fiber diameter.

Figure 2.

Hydration-induced diameter reduction of CSS nanofibers. (a) SEM images of as-spun CSS nanofibers and CSS nanofibers that were hydrated in 1x PBS for 72 h. (b) Diameter distribution of as-spun and hydrated CSS nanofibers.

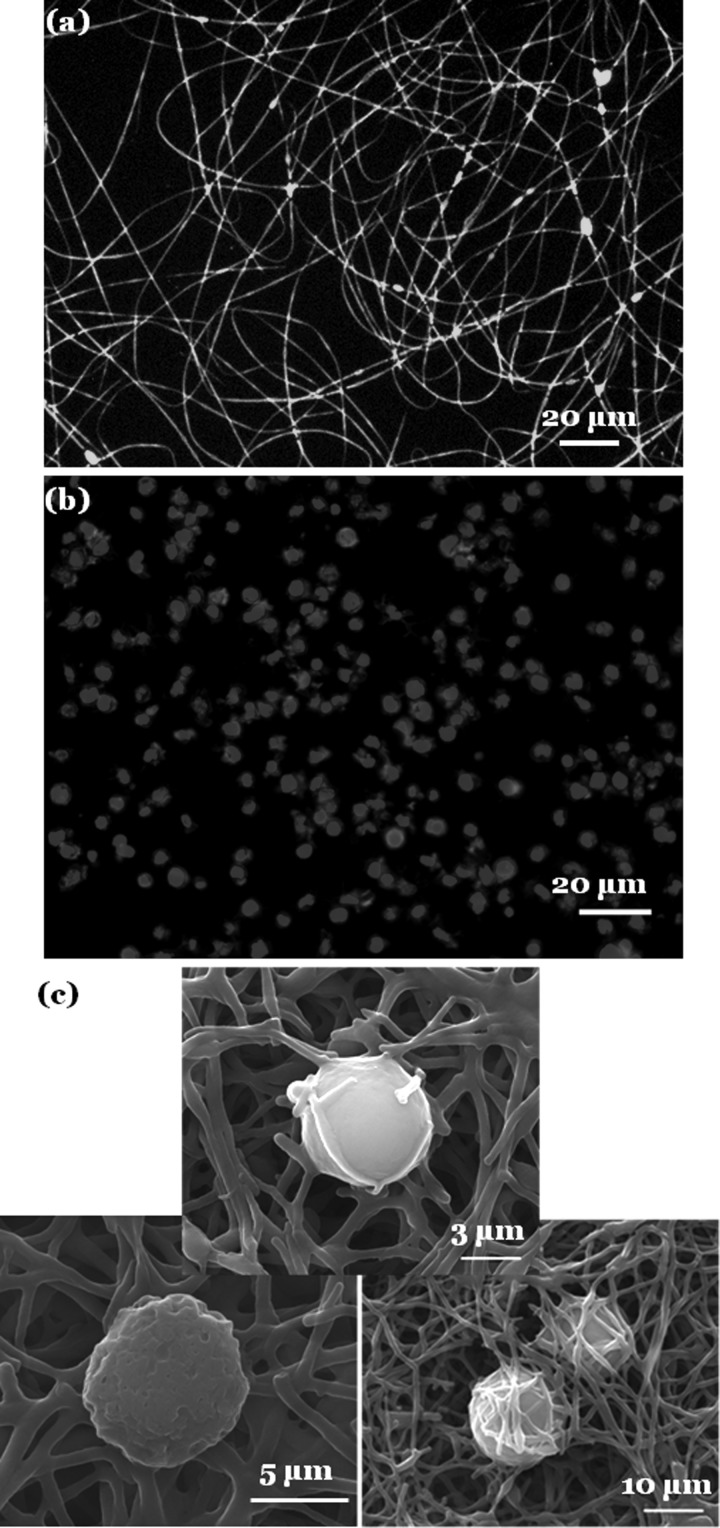

The ability of CSS nanofibers to functionally immobilize membrane-bound molecules was tested using phosphatidylethanolamine (DPPE) lipids conjugated with fluorescent nitrobenzoxadiazole (NBD) and murine anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) that specifically targets B lymphocytes. The former has alkyl chains and the latter has hydrophobic amino acids, which function as membrane-anchoring domains. In our first experiment, CSS nanofibers that were collected on glass slides at a low fiber density were incubated in an alcoholic solution of NBD-DPPE at a concentration of 30 μg/ml for 15 min. The treated nanofibers were imaged by an inverted fluorescent microscope (LEICA DMI 4000B). The good fluorescent labeling of the CSS nanofibers suggests that NBD-DPPE was stably adsorbed on the fiber surfaces [Fig. 3a].

Figure 3.

Functional immobilization of membrane-bound molecules on CSS nanofibers. (a) NBD-DPPE. (b) and (c) Anti-CD 20 Abs. Immunofluorecent (b) and SEM images (c) of Granta-22 cells captured on the anti-CD20 functionalized CSS nanofiber meshes. The cells were fixed and stained for nucleus with DAPI in blue and for actin with phalloidin in red.

In the second experiment, CSS nanofibers collected on glass slides at a high fiber density were incubated with a dilute PBS solution of anti-CD20 mAb (10 μl original anti-CD20 solution in 1 ml PBS) for 1.5 h. The immobilization of anti-CD20 mAb and the functionality of the immobilized mAb were assessed using a cell-capture assay. Briefly, the anti-CD20 modified CSS nanofibers were incubated in the suspension of human mantle cell lymphoma Granta-22 cells for 45 min, and the captured cells were stained for nucleus with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and for actin with phalloidin and viewed using a fluorescent microscope [Fig. 3b]. The density of the captured Granta-22 cells was determined to be 1363 ± 140 cells per mm2 (n = 5), which is even better than the density of captured CTCs using Ab-functionalized nanoposts or nanopillars.15

SEM analysis of the captured Granta-22 cells further revealed an interesting phenomenon. As shown in Fig. 3c, some cells were captured on the surfaces of the CSS fiber mesh, establishing adherent contacts with the nanofibers. Some cells were buried inside the CSS nanofibrous mesh, which displayed broken fibers around and/or near the capture cells. One cell was even wrapped by broken CSS nanofibers. We speculated that the capture process of Granta-22 cells on the Ab-functionalized CSS nanofibrous membranes was analogous to the capture of an insect by a spider's web. Specifically, the functional immobilization of anti-CD20 mAb rendered the CSS nanofibers sticky to the targeted cells. Like an insect caught by a spider's web,16 a cell intercepted by the “sticky” CSS nanofibers had limited freedom to roll around, breaking some fibers and dragging broken fibers with it. However, once the top layer of the CSS nanofibers was broken by an intercepted cell, the next layer of the “sticky” nanofibers would be exposed. Eventually, the cell would be wrapped by “sticky” CSS fibers and buried inside the fiber mesh. This is in marked contrast to a single-layer spider's web, from which an intercepted insect may struggle free.16 The morphologically stable yet mechanically flexible multi-layer CSS nanofibers, which can be deformed and even broken by a rolling cell, offer a unique strategy for the improved capture of targeted cells.

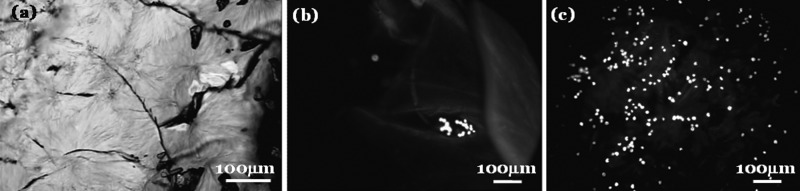

To elucidate how the nanoscale topologies of the electrospun CSS fibers affect cell capture, a control study was performed in a CSS film system. Specifically, CSS films were prepared by casting the hydrolyzed CSS solutions in a 48-well plate. The cast CSS films exhibited wrinkles and cracks on the order of several tens or even a few hundreds of micrometers [Fig. 4a]. The formation of cracks and wrinkles in the CSS films can be explained by a packing-constraint theory of wrinkling.17 Unlike the CSS nanofibers that can freely shrink in the fiber diameter direction, any in-plane shrinkage of the CSS films during the solvent evaporation and water immersion processes was largely constrained by the rigid substrate. As a result, tensile stress may be built up in the films, leading to the formation of cracks. Subsequently, a sudden release of heterogeneous tensile stress in the films upon cracking likely caused compression and wrinkling in some local areas. The large surface roughness of the CSS films has important implications in cell capture. For instance, when the non-functionalized CSS nanofibrous mesh was used to capture Grant-22 cells, very few cells were captured via non-specific interactions. However, when the non-functionalized CSS films were used for the cell-capture study, several Granta-22 cells were physically trapped in the presumably sub-millimeter cracks or groves on the film surfaces [Fig. 4b].

Figure 4.

A control study using CSS films. (a) Optical image of CSS films. Cracks (in black) appeared on the films. Immunofluorecent image of Granta-22 cells captured on the non-functionalized (b) and anti-CD20 functionalized CSS films (c). The cells were fixed and stained for nucleus with DAPI.

Following the same procedure used for the CSS nanofiber study, the cast CSS films were functionalized with anti-CD20 mAbs and examined using the cell capture assay [Fig. 4c]. Compared to the anti-CD20 functionalized nanofibrous mesh, the functionalized CSS films captured Granta-22 cells at a much lower density of 350 ± 50 cells per mm2 (n = 5). A number of factors may explain why the anti-CD20 coated CSS nanofibers displayed superior cell capture efficiency over their film counterparts. First, the large specific areas of the CSS nanofibers enhanced the cell-substrate interactions at both the whole-cell and sub-cellular levels. Second, the sub-micrometer surface roughness of the CSS nanofiber meshes promoted cell adhesions to the substrate, as accumulating evidence suggests a preferential attachment and growth of different cells on substrates with nanoscale roughness.18 Last, the unconstrained shrinkage of the CSS nanofibers in the diameter direction upon water hydration may facilitate the stable immobilization of anti-CD20 by tightening the inserted hydrophobic amino acids of the antibodies. In contrast, any potential shrinkage of the CSS films was largely limited by the rigid substrate of cell-culture wells.

In summary, a biomimetic strategy was employed to functionalize electrospun organic-inorganic cholesteryl-succinyl silane nanofibers with membrane-bound molecules, including NBD-conjugated phospholipids and antibodies containing transmembrane domains. An insert-and-tighten mechanism has been proposed for the immobilization of membrane-bound molecules on the CSS nanofibers. Subsequently, the anti-CD20 functionalized CSS nanofibers displayed a greater ability to capture Granta-22 cells than their film counterparts, suggesting that nanotopography played an important role in antibody immobilization and cell capture.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (EB009160) and National Science Foundation (CMMI0855890), and National Science Foundation of China (2007AA03Z316, 30970829).

References

- Allard W. J., Matera J., Miller M. C., Repollet M., Connelly M. C., Rao C., Tibbe A. G. J., Uhr J. W., and Terstappen L. W. M. M., Clin. Cancer Res. 10(20), 6897 (2004). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagrath S., Sequist L. V., Maheswaran S., Bell D. W., Irimia D., Ulkus L., Smith M. R., Kwak E. L., Digumarthy S., Muzikansky A., Ryan P., Balis U. J., Tompkins R. G., Haber D. A., and Toner M., Nature 450(7173), 1235 (2007). 10.1038/nature06385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivacic R. T., Ladanyi A., Curry D. N., Hsieh H. B., Kuhn P., Bergsrud D. E., Kepros J. F., Barbera T., Ho M. Y., Chen L. B., Lerner R. A., and Bruce R. H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101(29), 10501 (2004). 10.1073/pnas.0404036101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. T., Liu K., Liu J. A., Yu Z. T. F., Xu X. W., Zhao L. B., Lee T., Lee E. K., Reiss J., Lee Y. K., Chung L. W. K., Huang J. T., Rettig M., Seligson D., Duraiswamy K. N., Shen C. K. F., and Tseng H. R., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 50(13), 3084 (2011). 10.1002/anie.201005853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha Z. B., Cohn C. M., Dai Z. F., Qiu W. G., Zhang J. H., and Wu X. Y., Adv. Mater. 23, 3435 (2011). 10.1002/adma.201101516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N. A., Deng Y. L., Tai Q. D., Cheng B. R., Zhao L. B., Shen Q. L., He R. X., Hong L. Y., Liu W., Guo S. S., Liu K., Tseng H. R., Xiong B., and Zhao X. Z., Adv. Mater. 24(20), 2756 (2012). 10.1002/adma.201200155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y., Tan J. F., Asghar W., Kim Y. T., Liu Y. L., and Iqbal S. M., J. Phys. Chem. B 115(47), 13891 (2011). 10.1021/jp205511m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. H., Cohn C. M., Zha Z. B., Dai Z. F., and Wu X. Y., Appl. Phys. Lett. 99(10), 103702 (2011). 10.1063/1.3635783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurtenberger P., Scartazzini R., Magid L. J., Leser M. E., and Luisi P. L., J. Phys. Chem. 94(9), 3695 (1990). 10.1021/j100372a062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M. G., Layman J. M., Cashion M. P., and Long T. E., Science 311(5759), 353 (2006). 10.1126/science.1119790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W. G., Huang Y. D., Teng W. B., Cohn C. M., Cappello J., and Wu X. Y., Biomacromolecules 11(12), 3219 (2010); 10.1021/bm100469w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Qiu W. G., Cappello J., and Wu X. Y., Appl. Phys. Lett. 98(26), 263702 (2011). 10.1063/1.3604786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen K. L., Bhatia V. K., Gether U., and Stamou D., FEBS Lett. 584(9), 1848 (2010). 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt J., Padala C., Asuri P., Vutukuru S., Athmakuri K., Kumar S., Dordick J., and Kane R. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(20), 7107 (2009). 10.1021/ja9005282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarin A. L., Kataphinan W., and Reneker D. H., J. Appl. Phys. 98(6), 064501 (2005) 10.1063/1.2060928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Liu X. L., Su B., Li J., Jiang L., Han D., and Wang S. T., Adv. Mater. 23(38), 4376 (2011). 10.1002/adma.201102435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge T. A. and Zevenbergen J. M., Ethology 112(12), 1194 (2006). 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01277.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda E. and Mahadevan L., Phys. Rev. Lett. 90(7), 074302 (2003) 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.074302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile F., Tirinato L., Battista E., Causa F., Liberale C., di Fabrizio E. M., and Decuzzi P., Biomaterials 31(28), 7205 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]