Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that fibroblasts play a critical role in regulating inflammation during wound healing because they express several inflammatory mediators in response to bacteria. The objective of this study was to analyze the effects of lipopolysaccaride (LPS) on the immunomodulatory properties of vocal fold fibroblasts (VFF) derived from polyps, scar and normal tissue co-cultured with macrophages, to provide insight into their interactions during the inflammatory process. Fibroblasts were co-cultured with CD14+ monocytes and after 7 days, wells were treated with LPS for 24 and 72 hours. Culture supernatants were collected and concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-1β, and MCP-1 were quantified by ELISA. Normal VFF and CD14+ monocultures were used as controls. Twenty-four hours after LPS activation, macrophages co-cultured with polyp VFF had significantly increased expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-10 compared to controls (p<0.0001). In contrast, macrophages co-cultured with scar VFF had significantly lower expression of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-12 with significantly higher IL-10 compared to control (p<0.0001). After 72 hours, macrophages co-cultured with polyp VFF increased expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and TGF-β (p<0.01) and macrophages co-cultured with scar VFF significantly decreased their expression of IL-1β and IL-12 compared to control (p<0.0001). Scar VFF at both time points produced significantly lower levels of IL-8, MCP-1, IL-6 and TGF-β compared to controls (p<0.05). Based on our findings, VFF and macrophages secrete several inflammatory mediators that modify their diverse functions. Polyp and scar VFF may play a role in regulating abnormal inflammatory responses, which could result in excessive ECM deposition that disrupts the function of the vocal folds.

Keywords: macrophage, vocal fold, fibroblasts, scar, polyp, inflammation

1. Introduction

In the vocal fold lamina propria, fibroblasts and macrophages are the two most prominent cells orchestrating the complex inflammatory events involved in wound healing [1]. Prolonged inflammation (i.e. infection, vocal abuse) can lead to excess deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) resulting in benign vocal fold lesions [2] and dysphonia; however, the contribution of fibroblasts to the resolution of inflammation remains unclear. Recent evidence has suggested that fibroblasts contribute to fighting infection by synthesizing danger signals that can modify macrophage immunophenotype [3,4]. Such interactions may contribute to the formation of inflammatory lesions in the vocal fold and impair its normal biomechanical function which is vital for normal voice production.

Vocal fold fibroblasts (VFF) are essential to tissue homeostasis, because they provide a rich source of glycosaminogylcans, proteogylcans, elastin, and collagen molecules that influence the migration, growth, differentiation, and activity of neighboring cells [1,5,6]. Damage to the vocal folds due to external challenges (i.e. tobacco, reflux, bacteria), abusive behaviors (e.g., excessive voice use) or infection can alter fibroblast function. Beyond their structural function, very little is known about the role of fibroblasts as inflammatory mediators within the vocal folds. They are known to express a rich source of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and lipid mediators, including IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and cycloxygenase (COX-2) [7–11]. Fibroblasts from various other tissues have also been shown to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines that are involved in recruiting and activating macrophages, such as monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 or macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β [12,13], and produce several Toll like receptors (TLR) in response to microbial products [14]. Overt secretion of cytokines and chemokines are known to cause chronic inflammation in the vocal fold [15], however not all inflammatory events result in the formation of benign lesions [16]. Therefore, fibroblasts from normal and disease states may play a diverse role in their microenvironment that could influence the function of surrounding immune cells.

Macrophages exhibit functionally distinct phenotypes during wound healing that can both exacerbate the injury or initiate wound repair. These polarizations are broadly characterized into two subpopulations; classically activated macrophages (M1) exhibit pro-inflammatory responses (i.e. interleukin [IL]-12, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, inferon [IFN]-γ) and alternative activated macrophages (M2) exhibit anti-inflammatory responses (i.e. IL-10, IL-4) [17]. Classically activated macrophages are produced during cell-mediated immune responses to resist against infection by bacteria or other microorganisms [18]. Alternatively activated macrophages include several subtypes involved in wound healing or tissue regulation, which have suppressed inflammatory functions thereby inhibiting their host defense [18]. Our research group has previously demonstrated that normal VFF can modulate macrophage expression of HLA-DR and CD206 to a more anti-inflammatory phenotype [19]. However, after infection, endogenous danger signals produced in the microenvironment by fibroblasts can potentially alter macrophages phenotype and influence the resolution of inflammation [20].

The objective of this study was to analyze the complex inflammatory signaling between macrophages and VFF derived from polyps, scar or normal tissue. We hypothesized that the interaction between these cells plays an important role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammation in the vocal fold as evidenced by differences in macrophages cytokine expression with normal and pathologic VFF. In this study, we used an in vitro inflammatory co-culture model of macrophages and fibroblasts to analyze their paracrine signaling. We co-cultured fibroblasts with CD14+ cells for 7 days and then activated macrophages with LPS for 24 and 72 hours. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the outer membrane of a gram-negative bacterium causes activation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages [4]. Results suggest that functionally distinct subpopulations of macrophages exist in vitro and that our various VFF play a critical role in regulating macrophages inflammatory response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Human vocal fold fibroblasts

Primary fibroblast cell lines were harvested from normal, polyp and scar human vocal fold biopsies derived from four adult donors based on protocols approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) as previously described [21,22]. Polypoid tissue was obtained from a 24-year-old female undergoing microlaryngoscopy with bilateral excision of vocal fold polyps. Polyp tissue was carefully removed with cold instruments, making sure to preserve the overlying epithelium and with maximal preservation of the surrounding native lamina propria. The donor’s past medical and surgical histories were unremarkable.

For primary cell culture, true vocal fold tissue was cut into small pieces and suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.01 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate and 1x non-essential amino acid (NEAA) (all from Sigma Inc, St Louis). Cells were expanded out on uncoated plastic tissue culture dishes (Focal) at 37°C in 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. Once a confluent monolayer of cells was achieved, adherent cells were then harvested and passaged. Vocal fold fibroblast categorization and identification has previously been reported with this culture methodology [21]. Polyp, scar, T21 and T59 vocal fold fibroblasts (VFF) were expanded until passages six to eight for use in this study.

2.2 Human monocyte isolation

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected from buffy coat samples obtained from normal healthy donors using density grade centrifugation (Interstate Blood Bank, TN). Pure populations of CD14+ cells were isolated by magnetic bead separation methods as previously described [19,23]. Briefly, cell suspension was incubated with anti-human CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA) for 15 minutes at 4° C degrees and cells were separated using an AutoMACS Pro Separator (Milenyi Biotech) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Human monocytes separated from buffy coats were then frozen at −80° C in freezing media (70% phenol red free RPMI –1640 supplemented with 20% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine-alanine, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% NEAA, and 10% DMSO) and stored at −180° C until used. This method has previously been shown to yield >95% cell viability and approximately 35% of CD14+ monocytes at a 1 ×106 starting concentration will differentiate into CD14+/CD206+ macrophages after 7 days culture as previously described [19,23].

2.3 Cell Culture

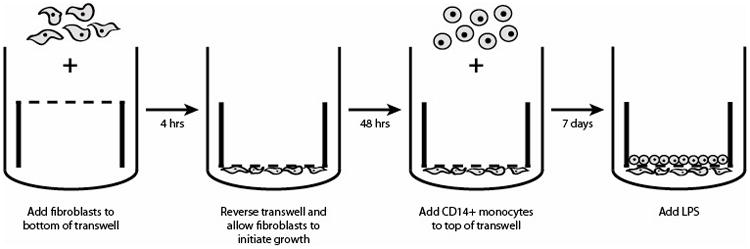

To induce monocyte differentiation into macrophages in the presence of VFF, we co-cultured fibroblasts with CD14+ cells for 7 days (Figure 1). VFF (20 × 105) suspended in 200uL R10 media (phenol red free RPMI –1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine-alanine, 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% NEAA) supplemented with an extra 10% FBS to facilitate cell adhesion were seeded on the basolateral underside of a tissue culture treated transwell (0.4 um pore; Millicell). After incubation at 37°C 5% CO2 for 4 hours, transwells were gently turned over and 1.5mL of R10 media was added to the top and bottom of each transwell. Fibroblasts were incubated for 48 hours to allow cells to initiate growth on the transwell. Purified CD14+ monocytes were thawed and washed, then seeded on to the apical side of the transwell at a concentration of 1 × 106 per well and cultured for seven days at 37° C in 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. For control conditions, fibroblasts (i.e. T21, T59, polyp, scar) and CD14+ cells were seeded alone on the transwell. R10 media was changed on day 4 as previously described [19]. Briefly, media was removed and centrifuged at 1200 RPM for 10 minutes to collect any non-adherent CD14+ cells. These cells were then suspended in fresh media and added back to the appropriate well on the apical side.

Figure 1.

Schematic of culture methods implemented to investigate the interaction between macrophages and fibroblasts derived from polyp, scar and normal tissue.

Following the 7th day of co-culture, media including non-adherent CD14+ cells was aspirated from each well. Fresh R10 media was added to the bottom of each well and R10 culture medium containing 10μg/mL LPS from Escherichia coli O26:B6 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to the apical side of each well where macrophages were culturing. Non-stimulated cells were used as controls.

Our experimental protocol was based upon work previously published, demonstrating significant increases in fibroblast proliferation during co-culture with macrophages on polystyrene [19]. By day 7, VFF were confluent on plates and after harvesting co-culture conditions CD14+ macrophages were undetectable using flow cytometry techniques [19]. Transwell co-culture methods were used to allow for long-term co-culture and they prevent direct physical contact between fibroblasts and macrophages, keeping them 10μm apart.

2.4 Fibroblast proliferation assay

To compare the growth rate of fibroblasts derived from polyp and scar vocal fold tissues to normal T21 and T59 VFF, cells were harvested and stained with trypan blue, then manually counted using a hemocytomer. VFF were seeded in triplicate on a 12-well plate at 50 × 104 cells/well and untreated conditions were quantified after 3, 5, 6, and 7 days culture. To test the viability and differences in growth rate of VFF after LPS treatment polyp, scar and normal (T21 and T59) VFF were grown out in triplicate to 80% confluence (4 days) and wells were treated with or without LPS (10μg/mL) and quantified after 24 or 72 hours.

2.5 ELISA of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines

To investigate immunomodulatory properties of polyp, scar and normal T21 and T59 VFF on macrophage phenotype, VFF and macrophage co-cultures were treated with LPS in duplicate for 24 and 72 hours. Following 7 days of co-culture, media including non-adherent CD14+ cells was aspirated from each well. Fresh R10 media was added to the bottom of each well and R10 culture medium containing 10μg/mL LPS was added to the apical side of each well where macrophages were culturing. After 24 and 72 hours of LPS stimulation, supernatants from both the well and transwell were combined into a single vial and centrifuged at 1200RPM for 5 min to remove any debris and stored at −80° C. Non-stimulated cells were used as controls. To determine differences in cytokine and chemokine expression, ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, USA). The following human analytes were measured from 100 μL of culture supernatants from each well: tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-1β and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. Standard curves were used to measure the quantity of the analytes in each sample. R10 media with and without LPS was analyzed with each assay to control for non-specific staining.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Separate, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze differences in proliferation rate across VFF cell type and treatments (with or without LPS). Mean and standard deviation (SD) values represent differences across cell culture replicates. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to test for differences in protein expression levels across groups, days and group by day interactions. If the F-test revealed significant differences at the 0.05 level, pairwise comparisons were used to determine statistical differences between samples (Fisher’s least squares means). A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Mean and SD values represent differences across cell culture replicates. Statistical interpretations were made using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

A separate repeated measures ANOVA was also utilized to determine significant differences between scar and polyp co-culture and monoculture conditions. Samples were normalized by comparing protein (IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, TGF-β) expression levels in polyp VFF against the average of T21 VFF conditions and scar VFF against the average of T59 VFF conditions at each discrete time point. This accommodated the differences in proliferation rate between VFF. If the F-test revealed significant differences at the 0.05 level, pairwise comparisons were used to determine statistical differences between samples (Fisher’s least squares means).

3. Results

3.1 Fibroblast proliferation rate

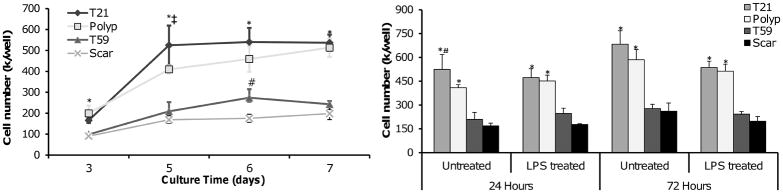

Growth curves of polyp, scar, T21 and T59 VFF were determined by cell counts of trypsinized cells after 3, 5, 6, and 7 days culture. Results are presented in Figure 2A as the mean ± SD of cell culture replicates. T21 and polyp VFF had statistically higher proliferation rates than the T59 and scar VFF at each time point (p<0.01). T21 VFF had significantly higher proliferation rates at day 5 compared to polyp (p<0.0297), while no significant differences were found between these two cell types at days 3, 6, and 7. T59 VFF had significantly higher proliferation rates at day 6 compared to scar (p<0.0463), while no differences were found at days 3, 5, and 7 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Human vocal fold fibroblasts (VFF) proliferation rates on tissue culture polystyrene. Polyp, scar, T21 and T59 VFF were seeded in a 12-well plate at 50 × 104 cells/well. Cell number was determined in triplicate by harvesting cells and staining with trypan blue. (A) VFF proliferation rates with no treatment on days 3, 5, 6 and 7. (B) VFF proliferation with and without treatment of LPS (10ng/mL) after 24 and 72 hours culture. * represent a statistical significance of p<0.01 when compared to scar and T59 VFF conditions. Statistical significance of p<0.05 is shown as ‡ when polyp is compared to T21 and # when scar is compared to T59.

To analyze differences in VFF growth rate with or without LPS treatment, cell counts were taken after 24 and 72 hours of stimulation. No significant differences were found between treated and untreated wells at both time points (Figure 2B). However, T21 and polyp VFF had statistically higher proliferation rates compared to T59 (p<0.0001; p>0.0003) and scar VFF (p<0.0001; p>0.0002).

3.2 Macrophages co-cultured with normal, polyp or scar VFF secrete unique cytokine profiles in response to LPS

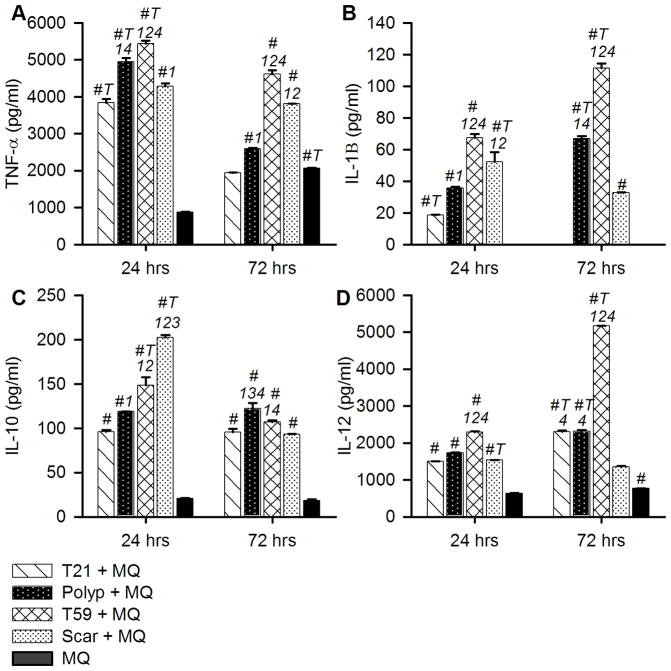

To analyze the influence of VFF on activated macrophages inflammatory response, we measured the expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-12 in the culture supernatant following 24 and 72 hours of LPS stimulation (Figure 3A–D; Tables 1–2). Non-stimulated macrophages in mono- or co- culture conditions produced minimal amounts of IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-10 below the standard curve (data not shown). Polyp, scar, T21 and T59 VFF monoculture controls did not express measurable quantities of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, or IL-10. Overall, macrophages co-cultured with T59 VFF had significantly higher expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 after 24 and 72 hours of LPS stimulation compared to polyp, scar, and T21 VFF co-cultures (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

VFF derived from polyps, scar and normal tissue modulate macrophages inflammatory response. After 7 days of co-culture non-adherent CD14+ cells were removed and each well was treated with 10ng/ml of LPS for 24 or 72 hrs. Cell culture supernatants were analyzed for (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-1β, (C) IL-10, and (D) IL-12 expression levels. Data is graphed as the mean concentration (pg/ml) ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.001 is shown as (1) T21 + MQ, (2) polyp + MQ, (3) T59 + MQ, (4) scar + MQ. Letters represent a statistical significance of p< 0.0001 when compared to # = macrophage only condition and T = hours 24 and 72 are compared within treatment groups.

Table 1.

Macrophage co-cultured with VFF cytokine expression

| TNF-α | IL-1β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Conditions | 24 hrs | 72 hrs | 24 hrs | 72 hrs |

|

| ||||

| T21 + MQ (1) | 3,838.52±10.71#T | 1,943.74±0.04 | 18.60±0.32#T | 0.00 |

| Polyp+ MQ (2) | 4,946.42±9.72#T14 | 2,586.13±2.37#1 | 35.64±0.87#1 | 66.93±1.48#T14 |

| T59 + MQ (3) | 5,432.23±8.59#T124 | 4,613.89±10.64#124 | 67.29±2.57#124 | 111.40±2.98#T124 |

| Scar + MQ (4) | 4,280.77±8.48#1 | 3,814.87±0.15#12 | 52.20±6.24#T12 | 32.65±0.40# |

| MQ (#) | 879.43±2.46 | 2,066.93±0.78#T | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Data is the mean concentration (pg/ml) ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.001 is shown as 1–4. Letters represent a statistical significance of p< 0.0001 when compared to # = macrophage only condition and T = hours 24 and 72 are compared within treatment groups.

Table 2.

Macrophage co-cultured with VFF inflammatory mediator expression

| IL-10 | IL-12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Conditions | 24 hrs | 72 hrs | 24 hrs | 72 hrs |

|

| ||||

| T21 + MQ (1) | 96.00 ±1.75# | 95.48 ±3.95# | 1,500.27 ±0.69# | 2,301.00 ±4.01#T4 |

| Polyp+ MQ (2) | 118.75 ±0.16#1 | 122.27 ±5.98#134 | 1,736.69 ±0.23# | 2,316.82 ±3.79#T4 |

| T59 + MQ (3) | 148.48 ±9.04#T12 | 106.86 ±1.94#14 | 2,288.59 ±2.95#124 | 5,170.09 ±0.34#T124 |

| Scar + MQ (4) | 202.09 ±2.79#T123 | 93.19 ±0.62# | 769.36 ±0.41#T | 678.03 ±1.88# |

| MQ (#) | 20.98 ±0.27 | 18.38 ±2.40 | 63.08 ±1.31 | 384.38 ±0.38 |

Data is the mean concentration (pg/ml) ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.001 is shown as 1–4. Letters represent a statistical significance of p< 0.0001 when compared to # = macrophage only condition and T = hours 24 and 72 are compared within treatment groups.

After twenty-four hours of LPS stimulation, macrophages co-cultured with scar VFF had the highest expression of IL-10 compared to all other co-culture conditions (p<0.0001) and significantly increased expression of TNF-α (p<0.0001) and IL-1β (p<0.0001) compared to T21 VFF co-cultures. Macrophages co-cultured with polyp VFF had significantly increased expression of TNF-α (p<0.0001), IL-1β (p<0.0001) and IL-10 (p<0.002) compared to T21 VFF co-cultures.

After 72 hours of LPS stimulation, macrophages co-cultured with scar VFF expressed significant increases in TNF-α (p<0.0001) and significant decreases in IL-12 compared to polyp and T21 VFF co-cultures (p<0.0001). Macrophages co-cultured with polyp VFF had the highest expression of IL-10 (p<0.01) after 72 hours compared to all other conditions and increased expression of TNF-α (p<0.0001) and IL-1β (p<0.0001) compared T21 VFF co-cultures.

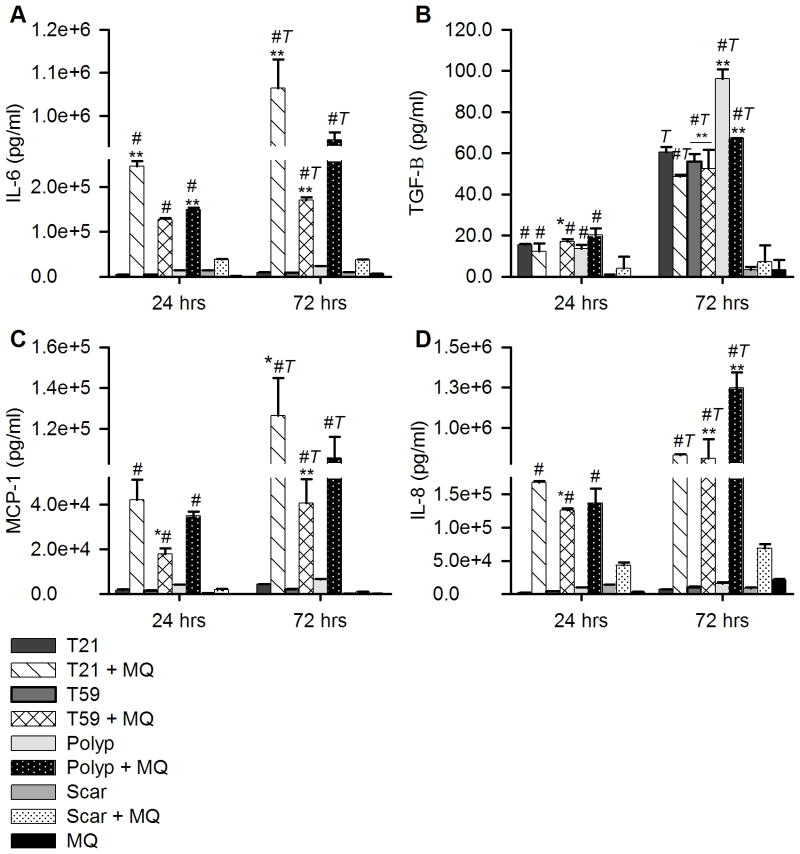

3.3 Expression of TGF-β, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 is lower in scar VFF co-cultured with macrophages

To investigate whether macrophages co-cultured with polyp or scar VFF modulate chemokine and growth factor signaling, we compared macrophages and fibroblasts co-culture conditions (Figure 4; Tables 3–4). VFF and macrophage monocultures were used as controls. Overall, the expression of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 was significantly higher in macrophage co-cultures with polyp, T21 VFF and T59 VFF after 24 and 72 hours of LPS stimulation compared to monocultures with VFF or macrophages (p<0.01). Additionally, the expression of TGF-β, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 was significantly higher 72 hours after activation of macrophages co-cultured with polyp (p<0.0001), T21 (p<0.0001) and T59 (p<0.02) VFF compared to 24 hours. Macrophages co-cultured with polyp VFF expressed lower levels of IL-6 and MCP-1 and higher levels of IL-8 and TGF-β after 72 hours compared to T21 VFF co-cultures (p<0.005). In contrast, scar VFF co-cultured with macrophages expressed significantly lower levels of IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and TGF-β after 24 (p<0.05) and 72 hours (p<0.0001) of activation compared to macrophages co-cultured with T59 VFF. No significant differences were found between scar and T59 VFF monocultures expression levels of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1. Interestingly, T59 VFF significantly increased expression level of TGF-β after 72 hours of activation compared to scar VFF (p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

VFF chemokine and growth factor expression. After 7 of co-culture non-adherent CD14+ cells were removed and each well was treated with 10ng/ml of LPS for 24 or 72 hrs. Data is graphed as the mean concentration (pg/ml) of (A) IL-6, (B) TGF-β, (C) MCP-1, (D) IL-8 in the supernatant ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.01 is shown as * and p<0.0001 is shown as ** compared to normal fibroblast monoculture or co-culture control. Letters represent a statistical significance of p< 0.001 when compared to # = macrophage only condition and T = hours 24 and 72 are compared within treatment groups.

Table 3.

Macrophage and VFF chemokine expression

| MCP-1 | IL-8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Conditions | 24 hrs | 72 hrs | 24 hrs | 72 hrs |

|

| ||||

| T21 | 1,711.06 ±315.94 | 4,393.67 ±39.41 | 2,180.97 ±6.06# | 7,044.32 ±28.84#T |

| T21 + MQ | 42,133.80 ±8878.72# | 126,471.00 ±18383.51*#T | 167,468.00 ±2692 | 831,832.00 ±6588 |

| T59 | 1,520.57 ±199.66 | 2,157.37 ±275.56 | 4,468.31 ±51.94*# | 9,827.96 ±1321.29**#T |

| T59 + MQ | 17,968.25 ±2520.76*# | 40,490.80 ±10915.90**#T | 126,395.20 ±2708.8 | 812,992.00 ±118534 |

| Polyp | 4,194.66 ±93.73 | 6,480.58 ±289.49 | 9,954.09 ±58.45# | 15,603.93 ±2374.02**#T |

| Polyp + MQ | 34,892.45 ±1905.15# | 105,560.25 ±10433.29#T | 136,818.40 ±21500 | 1,249,194.00 ±95680 |

| Scar | 379.45 ±1.51 | 121.33 ±11.65 | 14,068.89 ±315.54 | 8,350.16 ±1579.5 |

| Scar + MQ | 1,944.96 ±440.54 | 931.89 ±55.17 | 43,440.80 ±4312 | 68,738.40 ±6624 |

| MQ | 64.50 ±18.63 | 249.10 ±17.82 | 2,930.92 ±479.92 | 21,066.80 ±1333.94 |

Data is the the mean concentration (pg/ml) ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.01 is shown as * and p<0.0001 is shown as ** compared to normal fibroblast monoculture or co-culture control. Letters represent a statistical significance of p< 0.001 when compared to # = macrophage only condition and T = hours 24 and 72 are compared within treatment groups.

Table 4.

Macrophage and VFF growth factor expression

| IL-6 | TGF-β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Conditions | 24 hrs | 72 hrs | 24 hrs | 72 hrs |

|

| ||||

| T21 | 4,619.59 ±111.19 | 8,992.30 ±947.88 | 15.40 ±0.49# | 60.50 ±2.65T |

| T21 + MQ | 246,799.20 ±10915.2**# | 1,064,524.00 ±66442**#T | 12.31 ±3.83# | 48.58 ±0.90#T |

| T59 | 4,265.52 ±262.71 | 8,748.90 ±125.12 | 0.00 0.00 | 55.97 ±3.59**#T |

| T59 + MQ | 127,656.00 ±2861.6# | 170,712.00 ±6146.6**#T | 16.95 ±1.17*# | 52.54 ±8.98**#T |

| Polyp | 13,967.70 ±16.57 | 23,402.89 ±692.79 | 13.60 ±1.83# | 96.22 ±4.54**#T |

| Polyp + MQ | 149,799.20 ±4023.2**# | 943,844.00 ±17980#T | 20.22 ±3.16# | 67.33 ±0.08**#T |

| Scar | 14,275.65 ±40.77 | 9,831.93 ±538.20 | 0.40 ±0.57 | 3.26 ±1.46 |

| Scar + MQ | 38,596.00 ±1030.8 | 37,176.80 ±692.00 | 4.03 ±5.69 | 7.19 ±7.90 |

| MQ | 1,470.79 ±7.17 | 6,926.59 ±146.89 | 0.00 0.00 | 3.37 ±4.77 |

Data is the mean concentration (pg/ml) ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.01 is shown as * and p<0.0001 is shown as ** compared to normal fibroblast monoculture or co-culture control. Letters represent a statistical significance of p< 0.001 when compared to # = macrophage only condition and T = hours 24 and 72 are compared within treatment groups.

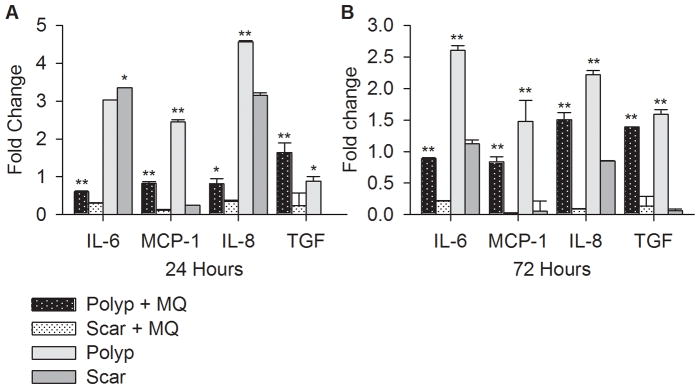

3.4 Polyp versus Scar VFF expression

To directly compare polyp and scar VFF expression of IL-6, MCP-1, IL-8, and TGF-β, we normalized the cytokine expression levels to control for differences in fibroblasts proliferation rate and age of donors. Results are presented in Figure 5 as the mean ± SD of the ratio (fold change) between polyp and T21 VFF or scar and T59 VFF. After 24 and 72 hours of LPS stimulation, polyp VFF co-cultured with macrophages expressed significantly higher IL-6, MCP-1, IL-8, and TGF-β compared to scar co-cultures. Polyp VFF monocultures expressed significantly higher MCP-1, IL-8 and TGF-β compared to similar conditions with scar VFF. Interestingly, scar VFF monocultures produced significantly higher IL-6 compared to polyp monocultures.

Figure 5.

Comparison of IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and TGF-β expression levels in polyp VFF to scar VFF. Expression levels were normalized by comparing polyp VFF against the average of T21 VFF conditions and scar VFF against the average of T59 VFF conditions at each discrete time point. Data is graphed as the mean fold change ± SD. Statistical significance of p<0.01 is shown as * and p<0.0001 is shown as ** compared to monoculture or co-culture conditions.

4. Discussion

Historically, fibroblasts were thought to be passive players in the host immune response primarily responsible for ECM production [24]; however, recent evidence argues against this theory, demonstrating that fibroblasts express TLR in response to microbial components and produce several inflammatory cytokines that modulate the inflammatory process [14]. In the current study, we hypothesized that the complex network of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors produced during interactions between fibroblasts and macrophages play a critical role in the initiation and resolution of inflammation in the vocal fold. Our results showed that fibroblasts derived from scar, polyp and normal vocal fold tissue co-cultured with macrophages can modulate their paracrine signaling during early cytokine expression (i.e. TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12) and subsequent chemokine and growth factor expression (i.e. IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, TGF-β). This suggests that VFF are a component of the innate immune response, however they most likely play an indirect role in regulating host defense because VFF alone did not express several pro-inflammatory cytokines needed to activate macrophages. Therefore, VFF may serve an important role in determining the quantity and duration of the macrophage response. The ability to control the homeostatic balance during acute stages of wound healing is critical to the resolution of inflammation and prevention of benign vocal fold lesions.

Vocal fold polyps are a benign lesion characterized by structural and genetic abnormalities, such as decreases in fibronectin and over expression of collagen and angiogenesis molecules [25]. Although periods of vocal abusive behaviors are thought to lead to tissue changes, the pathogenesis of vocal fold polyps is unknown [26–28]. Our data demonstrate that polyp VFF stimulated a stronger pro-inflammatory response from LPS-activated macrophages. This suggests that both fibroblasts and macrophages contribute to the inflammatory state found in polyp vocal fold lesions. Even though macrophages resembled a classical activated phenotype of high TNF-α and IL-12 with both T21 and polyp VFF, there was a marked decrease in IL-1β expression with T21 VFF after 72 hours as opposed to polyp VFF. Previous studies have shown that IL-12 in synergy with other pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e. TNF-α and/or IL-1β), can increase the production of IFN-γ, which could further activate natural killer cells and T cells to the injury site [29]. Thereby suggesting that polyp VFF could stimulate a greater response from macrophages. Interestingly, IL-10 a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine was also highly expressed by macrophages co-cultured with polyp VFF which could counter balance the high expression of IL-1β and TNF-α pro-inflammatory cytokines found in this condition. Future work is crucial to determine if alterations in polyp fibroblast phenotype can be exploited to promote inflammatory resolution in the vocal fold lamina propria.

Fibroblasts are the most abundant cell type within the vocal fold polyp, therefore they are likely to make a major contribution to the inflammatory processes and ECM organization in the microenvironment [25]. Differences in chemokine expression levels between polyp and T21 VFF co-cultured with macrophages 72 hours post challenge, could deduce that VFF may play a role in determining the type of immune cells recruited after infection. Polyp VFF produced high levels of IL-8 and thereby would predominately recruit neutrophils to the site, which respond to this chemokine by phagocytosing apoptotic cells and debri. High expression of IL-8 has been previously reported in nasal polyps, which along with neutrophils recruit eosinophils and plasma cells to the site of the lesion [30,31]. Further studies are needed to identify the immune cells recruited during inflammation in polyp vocal fold tissues.

Vocal fold scar is a chronic debilitating pathology, which is characterized by increased collagen and fibronectin, as well as decreases in elastin, decorin and fibromodulin [32,33]. As with vocal fold polyps, the pathogenesis of vocal fold scarring is unidentified. Our data demonstrate that scar VFF strongly stimulated IL-10 expression from macrophages 24 hours after LPS-activation, while IL-1β and IL-12 were suppressed. The increase in IL-10 production may be correlated with reported decreases in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 found in these conditions [34]. Overexpression of IL-10 by macrophages during acute inflammation is characteristic of what Mosser and Edwards described as a regulatory phenotype (2008). Regulatory macrophages exhibit functions somewhere between alternative and classical phenotypes, responding to stimuli by dampening the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and co-stimulatory molecules, as well as cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α [4,18,34]. Our results suggest that scar VFF may inhibit macrophage function, which can predispose the host to infection [18]. Previous studies have found a link between overexpression IL-10 and the development of fibrosis, suggesting that it results in poor inflammatory resolution thereby influencing subsequent wound healing [35]. Further investigation is necessary to determine scar VFF extracellular stimuli that are most likely eliciting the macrophage signaling cascade and activating mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathways, which have been shown to regulate macrophage expression of IL-10 [36].

Although the acute inflammatory response associated with vocal fold scar development has been investigated [15,37–39], the role of inflammation during the remodeling stages of wound healing has yet to be determined. Higher IL-8 expression measured in scar VFF co-culture conditions may also elicit greater neutrophil recruitment, however further analysis is needed to determine if other chemokines are involved in directed migration of inflammatory cells. Scar VFF conditions produced markedly lower rates of MCP-1 and IL-8, suggesting that these conditions mildly promote chemotaxis in response to LPS and/or macrophages. This diminished response is indicative of immune tolerance, which would occur if either cell had previously been desensitized to an endotoxin [40]. However, the overt expression of TNF-α and IL-1β are contradictory to this rationale; therefore the dramatic reduction may be a result of paracrine effects between scar VFF and macrophages. Characterization of the proteins secreted by scar VFF that may be playing an antagonistic role is required before this conclusion can be made definitely.

LPS is known to stimulate TLR signaling in macrophages, resulting in an increase in chemokines that can amplify the inflammatory response through the recruitment of more leukocytes [4]. Our results show differences in LPS activated macrophage regulation of IL-8 and MCP-1 in all VFF co-cultures, suggesting distinct differences for these chemokines in the vocal fold during normal and pathologic states. Higher IL-8 expression found in polyp and scar VFF co-culture conditions may elicit greater neutrophil recruitment and play a key role in the formation of inflammatory benign lesions as this chemokine is also involved in recruiting lymphocytes [30]. Interestingly, normal VFF co-culture conditions produced similar, overwhelmingly high amount of chemokines. This suggests that chemokine levels remain stable in normal VFF, irrespective of age and differences in proliferation rates.

Our results indicate that VFF are involved in suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines and neutrophil recruitment, as well as inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation into cytotoxic T cells [41]. T21 VFF co-culture conditions produced increased levels of IL-6 after LPS stimulation compared to polyp co-culture conditions, which appears to correlate with a decrease in expression of TNF-α. Previous studies have shown that IL-6 production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells suppresses TNF-α expression during acute inflammation [41], which decreases the formation of tissue fibrosis [42]. In contrast, scar VFF co-cultured with or without macrophages produced minimal amounts of IL-6 or TGF-β1 compared to all other fibroblast conditions. The absence of TGF-β1 may be correlated with the overt expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β [43]. The overall low levels of TGF-β1 may also be a result of our co-culture model, because macrophages have been shown to produce higher amounts after phagocytosis of apoptotic cells [44]. Further analysis is needed to establish if abnormal decreases in production of these cytokines during wound healing are linked to the development of vocal fold scarring.

A limitation of our study was the narrow availability of human vocal fold donors from normal and lesioned tissue. Vocal fold tissue is difficult to acquire due to the debilitating effects that sampling vocal fold tissue would have on a person’s vocal function. In order to control for age differences we included two normal VFF cell lines most similar in age to our lesioned VFF, however it stands to reason that differences still exist. Although inflammation has been linked to development of benign lesions and fibrosis in the vocal fold, not all inflammatory events result in their formation. Fibroblasts from polyp and scar tissue may play a role in regulating abnormal, albeit differing, inflammatory responses, which could result in excessive ECM disposition and disrupt the function of the vocal folds. Further studies are needed, with a greater number of vocal fold fibroblasts and CD14+ monocyte donors to elucidate the receptors involved in the initiation and progression of inflammation found in this study.

5. Conclusions

We employed an in vitro co-culture inflammation model to investigate the paracrine signaling interaction between macrophages and VFF derived from benign lesions, scar and normal tissue. Based on our findings, human VFF secrete several inflammatory mediators that exhibit bidirectional communication patterns with macrophages and result in diverse functions. Overall, results suggest that cytokine and chemokine expression is regulated differently in fibroblasts derived from different lesion types. The balance between stimulatory and inhibitory cytokine expression by macrophages was most affected by scar fibroblasts, which suppressed the acute inflammatory response against LPS stimulation and modulated macrophages to an alternative phenotype. These results suggest that scar fibroblasts can interfere with macrophages activation and prevent them from providing cell-mediated immunity.

Highlights.

Investigated the interaction between macrophages and vocal fold fibroblasts.

Polyp VFF promoted high TNFα, IL-1β and IL-12 expression from activated macrophages

Scar VFF stimulated high IL-10 and low IL-12 expression from activated macrophages

Vocal fold fibroblasts may play an indirect role in the innate immune response.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: NIDCD - NIH grants R01 DC4336, DC9600, T32 DC009401

The authors thank Peiman Hematti, MD for isolation of CD14+ cells and Xia Chen, MD, Ph.D. for technical support with the in vitro model. We also thank Glen Leverson, Ph.D., Department of Surgery at the University of Wisconsin- Madison for statistical assistance. This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD grants R01 DC4336, DC9600 (S.L. Thibeault) and T32 Voice Science Training Grant DC009401 (S.N. King, M.E. Jette).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SK ST. Performed the experiments: SK FC MJ. Analyzed the data: SK FC. Wrote the paper: SK MJ ST. Edited manuscript: SK FC MJ ST.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Suzanne N. King, Email: kings@surgery.wisc.edu.

Fei Chen, Email: carolfchen@gmail.com.

Marie E. Jetté, Email: jette@surgery.wisc.edu.

Susan L. Thibeault, Email: thibeaul@surgery.wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Catten M, Gray SD, Hammond TH, Zhou R, Hammond E. Analysis of cellular location and concentration in vocal fold lamina propria. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118(5):663–7. doi: 10.1177/019459989811800516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen JK, Thibeault SL. Current understanding and review of the literature: Vocal fold scarring. J Voice. 2006;20(1):110–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingerslev HC, Ossum CG, Lindenstrom T, Nielsen ME. Fibroblasts express immune relevant genes and are important sentinel cells during tissue damage in rainbow trout (oncorhynchus mykiss) PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Mosser DM. Macrophage activation by endogenous danger signals. J Pathol. 2008;214(2):161–78. doi: 10.1002/path.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray SD. Cellular physiology of the vocal folds. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33(4):679–98. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Thibeault SL. Characteristics of age-related changes in cultured human vocal fold fibroblasts. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(9):1700–4. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817aec6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branski RC, Perera P, Verdolini K, Rosen CA, Hebda PA, Agarwal S. Dynamic biomechanical strain inhibits IL-1beta-induced inflammation in vocal fold fibroblasts. J Voice. 2007;21(6):651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branski RC, Zhou H, Sandulache VC, Chen J, Felsen D, Kraus DH. Cyclooxygenase-2 signaling in vocal fold fibroblasts. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(9):1826–31. doi: 10.1002/lary.21017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim X, Bless DM, Munoz-Del-Rio A, Welham NV. Changes in cytokine signaling and extracellular matrix production induced by inflammatory factors in cultured vocal fold fibroblasts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(3):227–38. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou H, Felsen D, Sandulache VC, Amin MR, Kraus DH, Branski RC. Prostaglandin (PG)E2 exhibits antifibrotic activity in vocal fold fibroblasts. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(6):1261–5. doi: 10.1002/lary.21795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Thibeault SL. Biocompatibility of a synthetic extracellular matrix on immortalized vocal fold fibroblasts in 3-D culture. Acta Biomater. 2010;6(8):2940–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Y, Liu Y, Fukuda K, Nakamura Y, Kumagai N, Nishida T. Inhibition by triptolide of chemokine, proinflammatory cytokine, and adhesion molecule expression induced by lipopolysaccharide in corneal fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(9):3796–800. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt DJ, Chamberlain LM, Grainger DW. Cell-cell signaling in co-cultures of macrophages and fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2010;31(36):9382–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Hori K, Ding J, Huang Y, Kwan P, Ladak A, et al. Toll-like receptors expressed by dermal fibroblasts contribute to hypertrophic scarring. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(5):1265–73. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welham NV, Lim X, Tateya I, Bless DM. Inflammatory factor profiles one hour following vocal fold injury. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(2):145–52. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thibeault SL, Duflo S. Inflammatory cytokine responses to synthetic extracellular matrix injection to the vocal fold lamina propria. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(3):221–6. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laskin DL. Macrophages and inflammatory mediators in chemical toxicity: A battle of forces. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22(8):1376–85. doi: 10.1021/tx900086v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson SE, King SN, Kim J, Chen X, Thibeault SL, Hematti P. The effect of mesenchymal stromal cell-hyaluronic acid hydrogel constructs on immunophenotype of macrophages. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17(19–20):2463–71. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song E, Ouyang N, Horbelt M, Antus B, Wang M, Exton MS. Influence of alternatively and classically activated macrophages on fibrogenic activities of human fibroblasts. Cell Immunol. 2000;204(1):19–28. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thibeault SL, Li W, Bartley S. A method for identification of vocal fold lamina propria fibroblasts in culture. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(6):816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jette ME, Hayer SD, Thibeault SL. Characterization of human vocal fold fibroblasts derived from chronic scar. Laryngoscope. 2012 doi: 10.1002/lary.23681. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: A novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(12):1445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckley CD. Why does chronic inflammation persist: An unexpected role for fibroblasts. Immunol Lett. 2011;138(1):12–4. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duflo SM, Thibeault SL, Li W, Smith ME, Schade G, Hess MM. Differential gene expression profiling of vocal fold polyps and reinke’s edema by complementary DNA microarray. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115(9):703–14. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rousseau B, Ge P, French LC, Zealear DL, Thibeault SL, Ossoff RH. Experimentally induced phonation increases matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene expression in normal rabbit vocal fold. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138(1):62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson ER, Ohno T, Abdollahian D, Garrett CG, Rousseau B. Effects of raised-intensity phonation on inflammatory mediator gene expression in normal rabbit vocal fold. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(4):567–72. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.04.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verdolini K, Rosen CA, Branski RC, Hebda PA. Shifts in biochemical markers associated with wound healing in laryngeal secretions following phonotrauma: A preliminary study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(12):1021–5. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: A proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen JS, Eisma R, Leonard G, Lafreniere D, Kreutzer D. Interleukin-8 expression in human nasal polyps. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117(5):535–41. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawankar R. Nasal polyposis: An update: Editorial review. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thibeault SL, Bless DM, Gray SD. Interstitial protein alterations in rabbit vocal fold with scar. J Voice. 2003;17(3):377–83. doi: 10.1067/s0892-1997(03)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rousseau B, Hirano S, Chan RW, Welham NV, Thibeault SL, Ford CN, et al. Characterization of chronic vocal fold scarring in a rabbit model. J Voice. 2004;18(1):116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O’Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147(11):3815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun L, Louie MC, Vannella KM, Wilke CA, LeVine AM, Moore BB, et al. New concepts of IL-10-induced lung fibrosis: Fibrocyte recruitment and M2 activation in a CCL2/CCR2 axis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300(3):L341–53. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00122.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma W, Lim W, Gee K, Aucoin S, Nandan D, Kozlowski M, et al. The p38 mitogen-activated kinase pathway regulates the human interleukin-10 promoter via the activation of Sp1 transcription factor in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(17):13664–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thibeault SL, Bless DM, Gray SD. Interstitial protein alterations in rabbit vocal fold with scar. J Voice. 2003;17(3):377–83. doi: 10.1067/s0892-1997(03)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousseau B, Hirano S, Chan RW, Welham NV, Thibeault SL, Ford CN, et al. Characterization of chronic vocal fold scarring in a rabbit model. J Voice. 2004;18(1):116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thibeault SL, Rousseau B, Welham NV, Hirano S, Bless DM. Hyaluronan levels in acute vocal fold scar. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(4):760–4. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200404000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaufmann A, Gemsa D, Sprenger H. Differential desensitization of lipopolysaccharide-inducible chemokine gene expression in human monocytes and macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30(6):1562–7. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1562::AID-IMMU1562>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schindler R, Mancilla J, Endres S, Ghorbani R, Clark SC, Dinarello CA. Correlations and interactions in the production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in human blood mononuclear cells: IL-6 suppresses IL-1 and TNF. Blood. 1990;75(1):40–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denis M. Interleukin-6 in mouse hypersensitivity pneumonitis: Changes in lung free cells following depletion of endogenous IL-6 or direct administration of IL-6. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;52(2):197–201. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prud’homme GJ. Pathobiology of transforming growth factor beta in cancer, fibrosis and immunologic disease, and therapeutic considerations. Lab Invest. 2007;87(11):1077–91. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(4):890–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]