Ten years ago, Atkin1 reckoned that the popularity of ‘paradigm shift’ in the titles of medical articles was waning and that ‘pushing the envelope’ was up and coming. Foreseeing that even the envelope’s days were numbered, he asked that medical authors should begin to think ‘outside the box’. These phrases are metaphors that have become clichés. A colleague who is a professional medical writer wrote to me that ‘Written clichés are the physical signs of clichéd thought. They are susceptible to fashion, and move easily from business school to politics, to public service administrators, to professional institutions, to lawyers, to doctors, and into their journals’. Privately, we mock these utterances; so what are the favoured phrases, and do we want them in our journals?

METHOD

I searched PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) in August 2011 using methods similar to a previous search for literary allusions.2 I thought of possible clichés and searched 5-year periods with the limit of titles of articles published in English. I used wild cards and Boolean operators as appropriate, for example, ‘paradigm AND (shift* OR shifting)’. I scanned lists for skewing by the titles of series or by multiple responses to articles; the totals may include occasional non-metaphorical use.

For each 5-year period, I corrected for the total number of articles published in English: 1971–1975 counted as unity, and the correction factor for 2006–2010 was 4.64. I adjusted the corrected total number arbitrarily to 100 for each compared cliché. I made no formal statistical comparisons.

RESULTS

Revisiting Atkin: paradigms, envelopes, and boxes

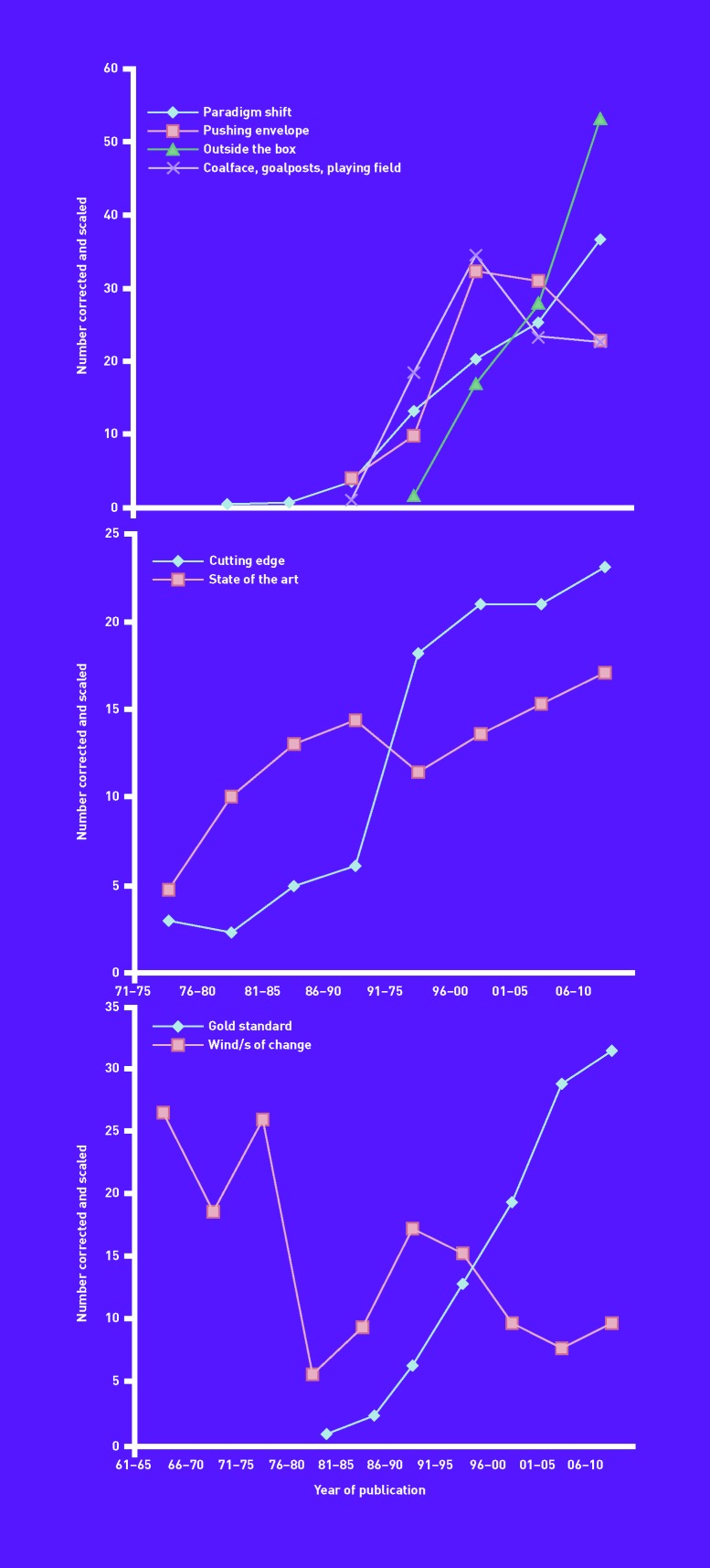

‘Paradigm shift’ continues to gain in popularity, but ‘pushing the envelope’ has faltered (Figure 1; top). Atkin should have had the courage of his conviction: ‘outside the box’ appeared first in 1995 and is surging ahead: there were 124 in 2006–2010, though this is still less than the 344 shifted paradigms. About one-tenth of articles published in 2006–2010 were classified as reviews. Unsurprisingly, clichés were generally more popular in reviews: nearly one quarter of paradigm-shifting articles were reviews.

Figure 1.

Number of clichés in medical article titles accessed via PubMed per 5-year period, corrected for number of publications per period and scaled up to a total of 100. Note the time covered is 1971–2010 for the top and middle, but 1961–2010 for the bottom.

Management speak: coalfaces, goalposts, and playing fields

Of coalfaces, moved goalposts, and levelled playing fields there were only 164 in total (Table 1). All three appeared around 1990 (previous occurrences were of actual playing fields and coalfaces). They peaked in the late 1990s (Figure 1; top), playing fields being the most popular. ‘Rubber hits the road’ appeared in 1985, but has not proved popular: eight in 2001–2005 and seven in 2006–2010.

Table 1.

Cliché, year of first appearance in a medical article title, and number of titles in articles published 1971–2010 accessed via PubMed

| Cliché | Year | N |

|---|---|---|

| State of the art | 1959 | 3518 |

| Gold standard | 1979 | 915 |

| Paradigm shift/s/ing | 1980 | 722 |

| Cutting edge | 1970 | 411 |

| Outside the box | 1995 | 200 |

| Wind/s of change | 1960 | 184 |

| Coalface goalposts and playing field | c. 1990 | 164 |

| Pushing the envelope | 1989 | 86 |

| Quantum leap | 1972 | 48 |

| Rubber and road | 1985 | 23 |

Forging ahead: cutting edges, states of the art, and quantum leaps

‘Cutting edge’ referred to surgical instruments before 1970; there have now been 411, and they continue cutting (Figure 1; middle). The Journal of Immunology started a series titled ‘Cutting edge: ….’ in 1998, which continues and is responsible for another 985. ‘State of the art’ is the longest lasting cliché that I found: the first is from 1959 (when it was a metaphor but, in medicine, not yet a cliché). There were 1052 art states in 2006–2010, 681 in reviews, and it is likely that more will be revealed (Figure 1; middle). ‘Quantum leap’ has not become popular since its appearance in 1972; there are only 48 altogether, although 19 of these were in 2006–2010.

Learning from history: winds of change and the gold standard

February 1960, UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave a famous speech in Cape Town, speaking of the ‘wind of change’ sweeping through the colonies that would lead to independence. In December 1960, the BMJ published the first ‘wind of change’ in a medical journal, about artificial respiration.3 It seems likely that the title was inspired by the speech. There were 11 wind or winds in 1961–1965, and they continue blowing gently (Figure 1; bottom). On the other hand, the gold standard was abandoned in 1931, but was first used in a title in 1979. It is the second most popular cliché (Table 1), and its use continues to increase (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

What starts as metaphor, intended to enliven language, ends as cliché, deadening it. Philip Howard described a cliché as a ‘stereotyped expression … used so many billions of times that it comes out of the mouth or typewriter without causing a ripple in the mind of the speaker … listener … or reader’.4 He described medicine’s most common title cliché, which he read in the British Telecom slogan ‘We’re responsible for a host of other state-of-the-art innovations’, as ‘using language like breaking wind’.5

Coalfaces, goalposts, and playing fields came into general use in Britain in the 1980s, and into medicine in the 1990s: presumably an infection from the increasing place of business in medical practice. For only one cliché, ‘wind of change’, is there clear evidence (Macmillan’s speech) of why clichés appeared when they did. ‘State of the art’, first in a medical title in 1959, was first recorded (as ‘status of the art)’ in 1889. ‘Cutting edge’ was first recorded in 1851, 120 years before its appearance as ‘The cutting edge of rehabilitation’.

‘Cutting edge’, as well as being as redundant as all the others, risks misunderstanding if used metaphorically about a subject such as surgery that uses cutting edges. An imaginative writer may rejuvenate the metaphor: ‘Innovations in lung volume reduction: the non-cutting edge’6 is not (yet) a cliché. ‘Cutting edge solutions for state of the art health care’ (reference suppressed) is an abomination.

The undeservedly popular ‘gold standard’ is misunderstood. The value of gold was fixed: it was not just as metal that it was immutable. As a metaphor for the best there is, it makes no sense in medicine, in which (we hope) the best is always changing. Perhaps the first use, ‘In search of the gold standard for compliance measurement’,7 was acceptable, but how would they have known? ‘One thousand bedside percutaneous tracheostomies in the surgical intensive care unit: time to change the gold standard’ (reference suppressed): there is always a better gold standard ahead. ‘Quantum leap’ is similarly misused, as a quantal change is the smallest possible change.

As science becomes more open and journals less formal, titles intended to grab attention are inevitable.2 That is fine, but please can we have some imagination, to stir our senses (‘Where the rubber meets the road: a cyclist’s guide to teaching professionalism’8), rather than repetition (‘Thinking outside the box: using metastasis suppressors as molecular tools’ (reference suppressed) to erode our enthusiasm.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Michael O’Donnell for the idea.

Provenance

Freely submitted; not externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The author has declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkin PA. A paradigm shift in the medical literature. BMJ. 2002;325:1450–1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman NW. From Shakespeare to Star Trek and beyond: a Medline search for literary and other allusions in biomedical titles. BMJ. 2005;331:1540–1542. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anon. The Wind of Change. BMJ. 1960;2(5216):1862–1863. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard P. The state of the language. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard P. Winged words. London: Hamish Hamilton; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ost D, Glassman L, Fein AM, Marcus P. Innovations in lung volume reduction: the non-cutting edge. Chest. 2004;126(1):6–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudd P. In search of the gold standard for compliance measurement. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139(6):627–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fryer-Edwards K, Baernstein A. Where the rubber meets the road: a cyclist’s guide to teaching professionalism. Am J Bioeth. 2004;4(2):22–24. doi: 10.1162/152651604323097682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]