Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO), generated by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) in bystander human CD8 T cells, augments the accumulation of allogeneically activated human CD8 T cells in vitro and in vivo. Here we report that iNOS-derived NO does not affect T cell proliferation but rather inhibits cell death of activated human CD8 T cells after activation by allogeneic endothelial cells in culture. Exogenous NO did not affect activation-induced cell death of human CD8 T cells but specifically reduced death of activated T cells due to cytokine deprivation. NO-mediated inhibition of T cell death did not involve cGMP signaling, and NO did not affect the expression of Bcl-2-related proteins known to regulate cytokine deprivation-induced cell death. However, NO inhibited the activity of caspases activated as a consequence of cytokine deprivation in activated T cells. This protective effect correlated with S-nitrosylation of caspases and was phenocopied by z-VAD.fmk and z-LEHD.fmk, pharmacological inhibitors of caspases. In summary, our findings indicate that NO augments the accumulation of activated human T cells principally by inhibiting cytokine deprivation-induced cell death through S-nitrosylation of caspases.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a bioactive gas known to modulate immune responses such as allograft rejection. High levels of NO can inhibit T cell responses while lower levels can increase T cell activation (1, 2). The effects of low-moderate levels of NO are attributed largely to its properties as either an activator of soluble guanylate cyclase, which results in the production of cGMP (3), or to its ability to post-translationally modify proteins primarily by S-nitrosylation (4). This latter modification is increasingly recognized to play an important role in the regulation of enzymatic activity and signal transduction, thereby crucially affecting processes such as cell growth and death (4).

In mammals, NO is produced by three isoforms of nitric oxide synthases (NOS): nNOS, iNOS, and eNOS. In rats and mice, iNOS expression by immune cells contributes to acute organ transplant rejection by causing early organ transplant injury (5), but its expression within heart allografts at later time points reduces the development of chronic rejection by inhibiting leukocyte function (6, 7). The role of iNOS in the regulation of human allogeneic T cell responses is poorly understood. It is not possible to simply extrapolate the role of iNOS from rodent models to the human system because iNOS expression is regulated very differently in human cells than in mouse and rat cells (8). This may lead to species-specific functions of iNOS. The differences in iNOS expression arise in part because the human iNOS gene promoter possesses no homology to the mouse or rat iNOS promoter (9, 10). iNOS is expressed in infiltrating macrophages and T cells within human allografts and its expression is correlated with increased graft injury (11, 12). Furthermore, using an humanized mouse model of T cell-mediated allograft artery rejection, we have reported that iNOS is expressed specifically within infiltrating human CD8 T cells that lack markers of conventional activation by antigen. Paracrine production of NO from these bystander T cells contributes to allograft artery rejection by increasing the number of activated T cells within arteries (13). However, the mechanism by which NO increases the accumulation of activated T cells is not known.

Cell death of activated T cells regulates the size and duration of immune responses. There are two main pathways by which activated T cells are proposed to undergo cell death: cytokine deprivation and activation-induced cell death (AICD) (14). Cytokine deprivation-induced cell death is caused by a lack of signals required to sustain T cell growth and survival. This lack of survival signals causes changes in the ratios of expressed pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, thereby resulting in the release of cytochrome c and other mitochondrial factors followed by activation of caspases (15). In addition to cytokine deprivation-induced cell death, repeated or prolonged encounter with antigen can lead to AICD, which is mediated by activation of death receptors such as Fas or TNFR (16, 17). Both of the mentioned death pathways are known to regulate heart transplant rejection (18).

In this report, we show that inhibition of iNOS in primary human CD8 T cells reduces the accumulation of activated T cells in response to allogeneic endothelium. iNOS inhibition does not affect T cell proliferation but significantly increases the number of activated T cells undergoing cell death. Using in vitro models of T cell death, we determine that exogeneous NO does not affect AICD but significantly reduces cytokine deprivation-induced cell death. The survival effects of NO correlate with inhibition of caspase activity and cysteine S-nitrosylation of these enzymes. Our data thus suggest that paracrine NO acts as a survival factor for allogeneically activated T cells by inhibiting cytokine deprivation-induced cell death.

Materials and Methods

Human cell isolation and culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (ECs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained as described with approval of the appropriate Institutional Review Board (19). ECs were cultured in M199 + 20% FCS. CD8 T cells were isolated from PBMC by positive isolation with Dynal magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (13). Allogeneic stimulation of CD8 T cells was performed by co-culture of allogeneic ECs and CD8 T cells in RPMI 1640 + 10% FCS (20). In all co-cultures CD8 T cells were stimulated with fresh EC every 5 days. In experiments examining the effects of iNOS, either PBS or 1400W (20 µM/day; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to the cultures.

Analysis of allogeneically stimulated T cells

To examine the accumulation of proliferated T cells, CD8 T cells were labeled with CFSE (0.5 µM; Invitrogen) prior to co-culture with allogeneic EC. After 12 days, T cells were harvested, stained with a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibody to CD8 (anti-CD8-PE), and analyzed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer. To examine cell death, CFSE-labeled T cells were harvested after 12 days, stained with anti-CD8-PE and propidium iodide (PI), and analysis of PI-staining performed on the CD8-positive, CFSElow population.

CD8 T cell proliferation was directly examined by BrdU labeling of T cells for 24h at day 8 of the co-culture, followed by fluorescence staining for BrdU and CD8 as per the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).

NO measurements

NO production was measured by quantifying nitrite concentration in the supernatant of cell cultures using a NO chemiluminescence analyzer (Sievers, Boulder, CO) as described (13).

Induction of cell death

To induce AICD, CD8 T cells were stimulated with plate bound anti-CD3 (1 µg; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 µg/mL; eBioscience) for four days, removed from stimulation, cultured in IL-2 (50 U/mL) for five days, and then re-stimulated with plate bound anti-CD3 (1 µg) for 20h. To examine the effects of NO, increasing concentrations of the NO donor NOC-18 (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) were added to T cells during re-stimulation with anti-CD3.

To study cytokine deprivation-induced cell death, CD8 T cells were stimulated either with EC in the presence of 3 µg/mL of phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma) or with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28, removed from stimulation, washed extensively, and then cultured in the absence of stimulation. In some experiments either the NO donor NOC-18, the cell permeable cGMP analogue 8-Br-cGMP (Sigma), or 50 µM of the multi-caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk or the caspase-9 inhibitor z-LEHD.fmk were added to cytokine- deprived cells.

Quantification of cell viability and cell death

Cell viability was determined with a MTS assay as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Cell death was examined by staining with Annexin V and PI as described (21).

Caspase activity assays

Caspase activity assays were performed as described (21) using fluorescence-emitting caspase-9 (LEHD.AMC) and caspase-3-like (DEVD.AMC; which detects activity of caspase-3,-6,-7) enzymatic substrates (Calbiochem).

Cell lysis and western blotting

Cytokine deprived CD8 T cells were lysed and Western blotting performed as described (13) using the following antibodies: rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (BD), mouse anti-Bcl-xL (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-Mcl-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), rabbit anti-Bim (Stressgen, Ann Arbor, MI), rabbit anti-PUMA (Sigma), and mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma).

Immunoprecipitation and detection of S-nitrosocysteine

Activated CD8 T cells cultured in IL-2 or undergoing cytokine deprivation were lysed. Caspase-9 and caspase-3 were immunoprecipitated with 4 µg/mL of monoclonal antibodies to caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) as described (22). Immunoprecipitates were Western blotted for S-nitrosocysteine under non-reducing conditions using a rabbit polyclonal antibody to this protein modification (Sigma), as well as with rabbit antibodies to total caspase-9 (BD) and caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis

Graphical data depict the average ± SD of the indicated measurements in representative experiments. Where indicated, a Student’s t-test was performed to determine statistical significance between groups. An alpha value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Inhibition of iNOS does not affect proliferation but increases cell death of allogeneically activated human CD8 T cells

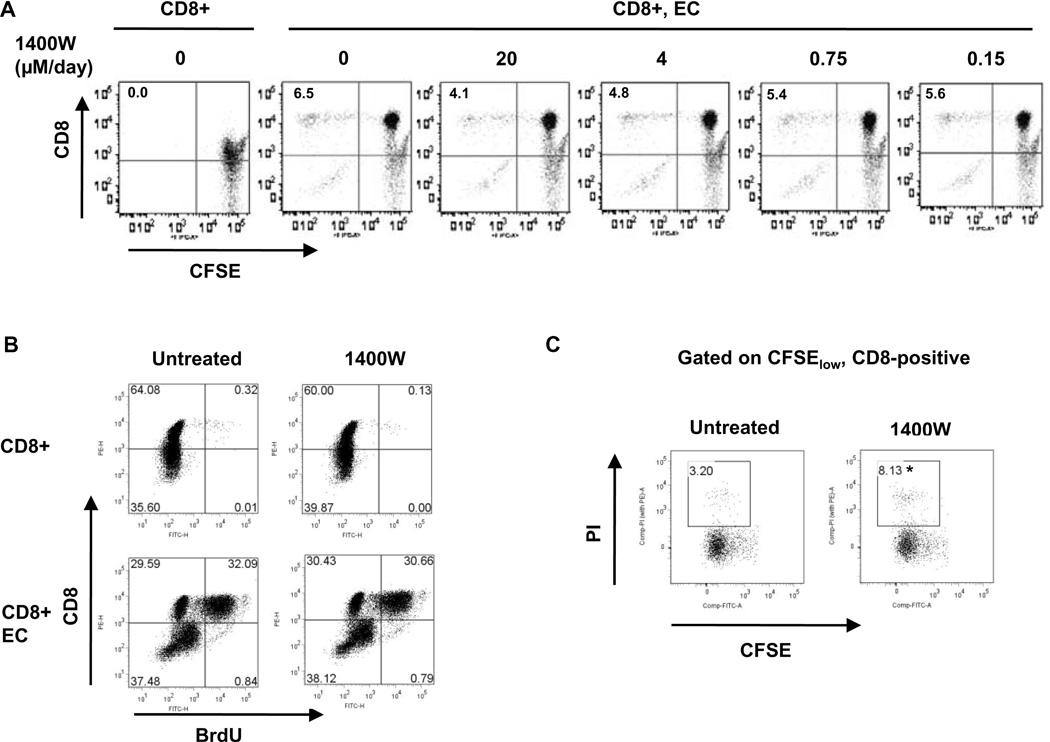

To investigate the mechanism by which iNOS-derived NO augments allogeneic human CD8 T cell responses, we co-cultured CFSE-labeled primary human CD8 T cells with allogeneic endothelium in the presence of the iNOS inhibitor 1400W or PBS vehicle control. 1400W reduced the accumulation of proliferated CD8 T cells in response to allogeneic ECs in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A). This was consistent with our previous findings showing that iNOS inhibition reduces the accumulation of proliferated CD8 T cells in this system by an average of 47.3 ± 3.0% (13). The dose responsive inhibition of 1400W on activated T cell accumulation correlated with the dose responsive inhibition of 1400W on iNOS-derived NO production from a mouse macrophage cell line in which maximal inhibition was observed at 20µM and partial effects observed at lower concentrations (data not shown). 1400W at 100 µM had no effect on basal NO production from ECs which utilize eNOS rather than iNOS (data not shown). Because CFSE analysis examines the accumulation of proliferated T cells over the entire course of the T cell response, both changes in cell proliferation and changes in the rate of cell death affect the size of the CFSElow population. T cell proliferation was directly examined by assaying for BrdU incorporation. Inhibition of iNOS did not affect the percentage of T cells undergoing proliferation in response to allogeneic ECs (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. iNOS-derived NO in T cells augments allogeneic human CD8 T cell responses by inhibiting cell death of activated T cells.

A. CFSE-labeled human CD8 T cells were co-cultured with allogeneic EC in the absence or presence of various concentrations of the iNOS inhibitor 1400W. After 12 days, cells were collected and stained for CD8, and the accumulation of proliferated CD8 T cells (upper left quadrant) was quantified by flow cytometry. B. Human CD8 T cells were co-cultured with allogeneic EC in the absence or presence of 1400W. The co-cultures were pulsed for 24h with BrdU on day 8. On day 9, cells were collected and stained for CD8 and BrdU, and the number of proliferating CD8 T cells quantified by flow cytometry (upper right quadrant). C. CFSE-labeled human CD8 T cells were co-cultured with allogeneic EC in the absence or presence of 1400W. After 12 days, the cells were collected and stained for CD8 and propidium iodide (to detect cell death). Three color flow cytometry was performed to determine the percentage of cell death in the proliferated CD8 T cell population (demonstrated as the percentage of CFSElowCD8-positive cells that were PI-positive). The presented plot shows PI uptake in the gated CFSElowCD8-positive population. *p<0.05 as compared to untreated group.

To determine whether iNOS inhibition affected death of activated T cells, CFSE-labeled CD8 T cells were co-cultured with allogeneic endothelium for 12 days in the absence or presence of 1400W and the proportion of CFSElowCD8-positive cells that were undergoing cell death quantified by quantitation of PI uptake. iNOS inhibition increased the number of allogeneically activated T cells undergoing cell death as compared to controls (Figure 1C). Over a series of four independent experiments from four different donors, iNOS inhibition significantly increased the amount of cell death of CD8 T cells that had been activated by allogeneic endothelium (2.2 ± 0.7 fold increase over controls; p < 0.05). These results indicate that iNOS in human CD8 T cells increases allogeneic responses primarily by increasing the survival of activated T cells.

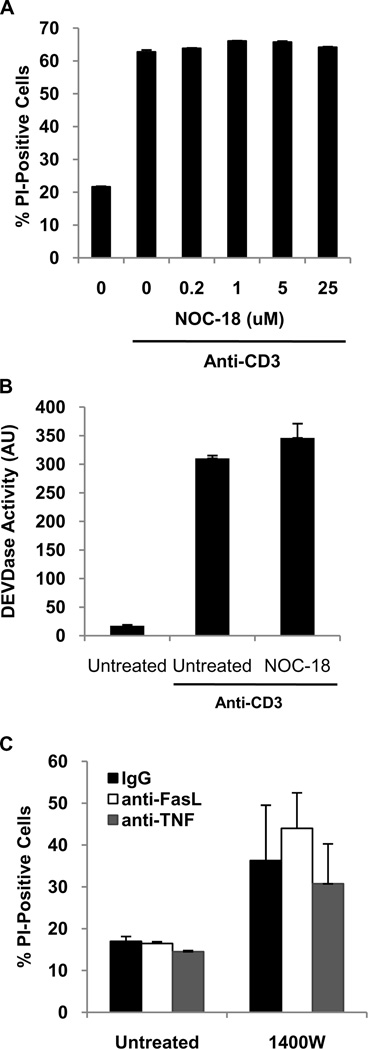

NO does not inhibit AICD

Following TCR stimulation, activated T cells may undergo cell death either through AICD or cytokine deprivation. The effect of NO on AICD was examined in CD8 T cells that had been polyclonally activated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28. To examine the effect of NO, the TCR restimulation was conducted in either the absence or presence of various concentrations of the NO donor NOC-18. Both cell death and caspase-3-like activity were measured after 20h. Neither AICD nor caspase-3-like activation were affected by a low level of NO (Figure 2A and B). Higher concentrations of NO (greater than 100 µM) are known to induce T cell death and this was similarly observed in our experiments (data not shown). Consistent with the lack of effect of NO on AICD, neutralizing antibodies to FasL and TNF had no effect on cell death of human CD8 T cells activated by allogeneic EC in the absence or presence of 1400W (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. NO does not inhibit AICD.

A. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 for four days, removed from TCR stimulation, cultured in IL-2 (50 U/mL) for five days, and then re-stimulated with anti-CD3 alone for 20h in the absence or presence of the NO donor NOC-18. Cell death was quantified by PI uptake. B. AICD was induced as described in A. in the absence or presence of NOC-18 (5 µM). After 20h, T cells were lysed and a fluorescence-based caspase-3 activity assay performed. C. CFSE-labeled human CD8 T cells were co-cultured with allogeneic EC in the absence or presence of 1400W. In addition, co-cultures were treated with IgG control antibodies, or neutralizing antibodies to FasL and TNF. After 12 days, cells were collected and stained with an antibody to CD8 and PI. Three color flow cytometry was performed to determine the percentage of cell death in the proliferated CD8 T cell population. The data presented are a graphical representation of the percentage of the gated CFSElowCD8-positive cells that were PI-positive.

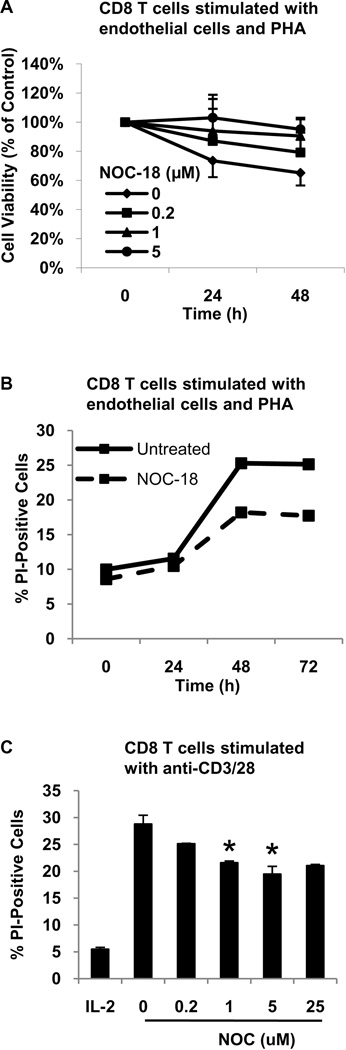

NO inhibits cytokine deprivation-induced cell death of activated human CD8 T cells

We next examined the effect of NO on cytokine deprivation-induced CD8 T cell death. Due to the difficulty of directly examining this cell death process in the small population of human CD8 T cells that recognize and respond to allogeneic EC, cytokine deprivation was induced in human CD8 T cells that were polyclonally activated with PHA and ECs. In this system, PHA provides a polyclonal TCR signal and ECs provide costimulation (23). The effect of NO on cytokine deprivation-induced cell death was determined by the addition of NOC-18 to CD8 T cells after their removal from stimulation with PHA and EC. T cells that were activated with PHA and EC underwent cell death in response to cytokine deprivation, as determined by a progressive reduction in cell viability and an increase in PI uptake (Figure 3A and B). The addition of low levels of NO increased cell viability and reduced the number of T cells undergoing cell death (Figure 3A and B). Cell death was evident after 24h and was maximal after 48h. Maximal inhibition of cell death by NO was observed with 5 µM of NOC-18. Endogenous iNOS did not influence cell death as activated T cells down-regulate iNOS (13) and eNOS (data not shown) expression, and the broad spectrum NOS inhibitor L-NAME had no effect (data not shown).

Figure 3. A low level of NO inhibits cytokine deprivation-induced cell death of activated human CD8 T cells.

A. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated with PHA and EC for four days, removed from TCR stimulation, washed extensively, and cultured in the absence of stimulation. Varying concentrations of NOC-18 were added to the culture and cell viability measured by MTS assay at the indicated time-points. B. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated as described in A. and cultured in the absence or presence of NOC-18 (5 µM). Cell death was measured at the indicated time points by PI uptake. C. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 for four days, removed from TCR stimulation, washed extensively, and cultured in IL-2 (10 U/mL) or in the absence of IL-2. Varying concentrations of NOC-18 were added to the culture and cell death measured by PI uptake at 48h. *p<0.04 as compared to untreated cytokine-deprived group.

Cytokine deprivation-induced cell death of human CD8 T cells was then examined after stimulation with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28. After removal from this type of TCR stimulation, T cells were either cultured in IL-2 (10 U/mL) to maintain cell viability or cytokine deprived to induce cell death. After 48h, cell death was evident in cytokine deprived CD8 T cells. The addition of low levels of NO dose-dependently reduced cytokine deprivation-induced CD8 T cell death, reaching a maximum inhibition at 5 µM of NOC-18 (Figure 3C). Consistent with the well-described biphasic effects of NO, higher levels of NO increased T cell death (data not shown). Over a series of three independent experiments with three separate donors, NOC-18 significantly inhibited cytokine deprivation-induced cell death at 1 and 5 µM (p<0.04).

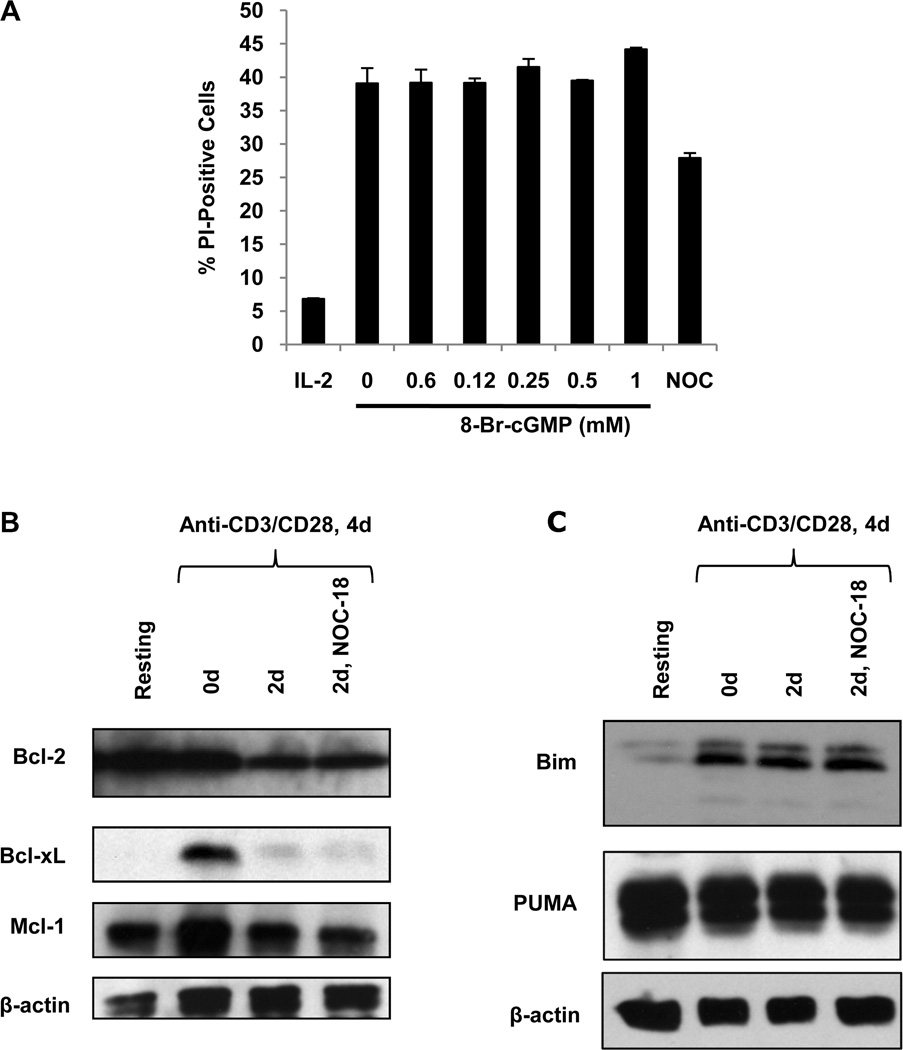

NO-mediated inhibition of cytokine deprivation-induced T cell death does not involve cGMP signaling

NO mediates biological effects through both cGMP-dependent and cGMP-independent pathways (3). To determine whether the survival effect of NO on activated T cells involves signaling through cGMP, a cell-permeable cGMP analogue (8-Br-cGMP) was added to CD8 T cells undergoing cytokine deprivation after stimulation with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28. 8-Br-cGMP did not affect cytokine deprivation-induced CD8 T cell death (Figure 4A), indicating that NO is acting through a cGMP-independent pathway.

Figure 4. NO does not reduce cytokine deprivation-induced cell death through a cGMP-dependent pathway or through modulation of the expression of Bcl-2 related proteins.

A. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 and cultured in IL-2 or cytokine deprived. Varying concentrations of the soluble cGMP analogue 8-Br-cGMP were added to cytokine deprived CD8 T cells and cell death measured at 48h by PI uptake. CD8 T cells that were cytokine deprived and treated with NOC-18 were included as a positive control. B. Cell lysates were collected from resting CD8 T cells (freshly isolated cells not stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28), from CD8 T cells that had been stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 but not cytokine deprived (0d), or from cytokine deprived CD8 T cells that had been cultured in the absence or presence of NOC-18 (5 µM) for 2 days. Western blots were performed to detect Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1. Detection of β-actin was used as a loading control. C. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated as described above and the cell lysates Western blotted for Bim, PUMA, and β-actin.

NO does not affect the expression of Bcl-2 and related proteins

Cytokine deprivation-induced cell death is known to proceed through a mitochondrial pathway that is regulated by the relative expression of various Bcl-2-protein family members (14). In particular, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 can inhibit this form of cell death, while Bim and PUMA are required for its induction (24--27). Therefore, we examined the effect of NO on the expression of these proteins in cytokine deprived CD8 T cells. Upon cytokine deprivation, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 protein levels were reduced in activated human CD8 T cells and NO did not affect their expression (Figure 4B). We also examined the levels of Bim and PUMA. In cytokine deprived CD8 T cells, both Bim and PUMA protein levels remained high and this was not affected by NO (Figure 4C).

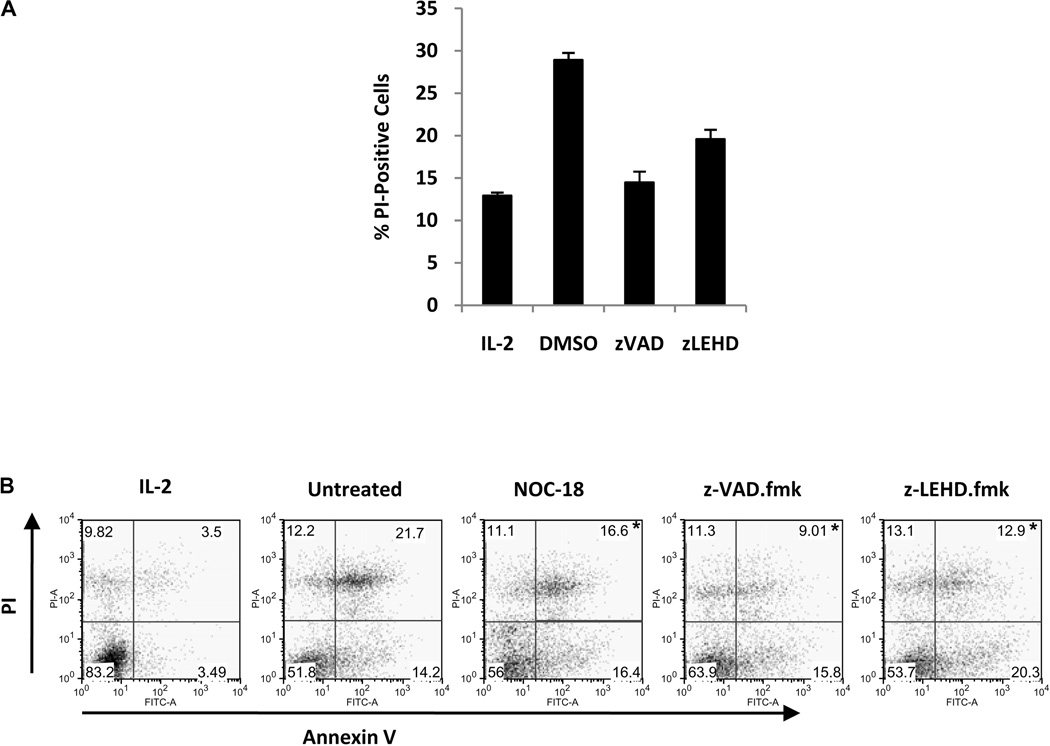

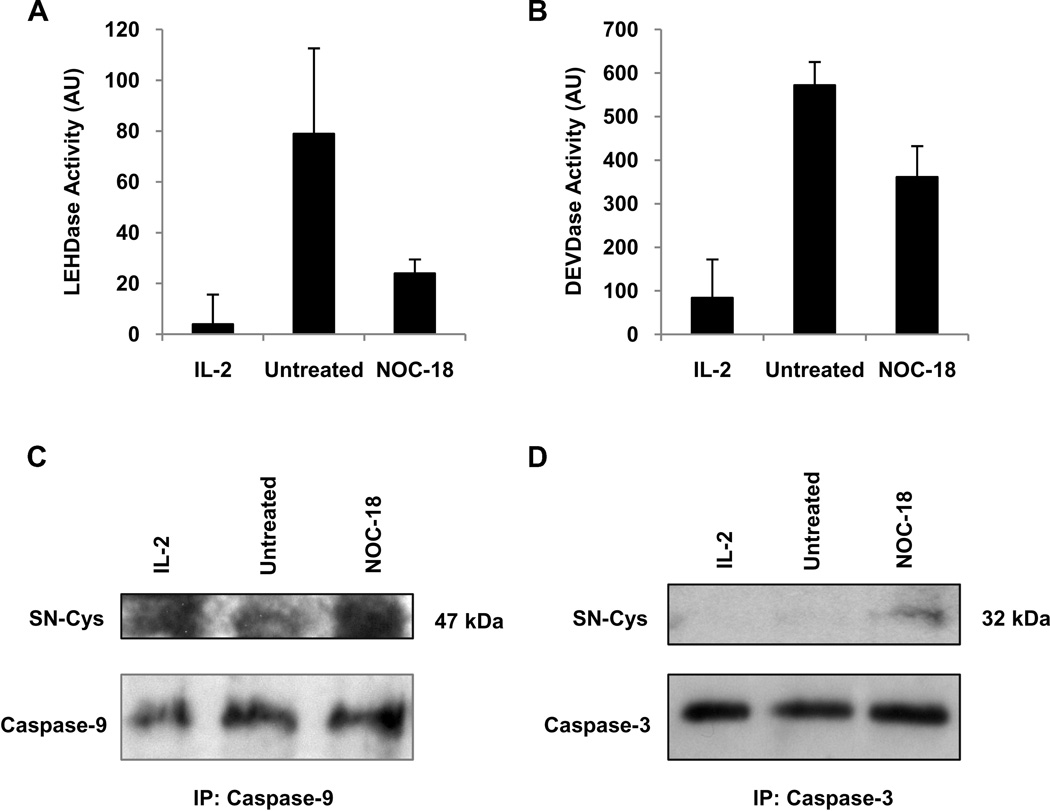

NO inhibits caspase-9 and caspase-3 activity through S-nitrosylation

Pharmacological inhibition of caspases reduces cytokine deprivation-induced death in mouse T cells (28). We observed that inhibition of multiple caspases with z-VAD.fmk reduced cytokine deprivation-induced cell death in human CD8 T cells and inhibition of caspase-9 with z-LEHD.fmk partially prevented this type of T cell death (Figure 5A). In addition, both NO and pharmacological caspase inhibition reduced similarly the percentage of dead cells, as measured by Annexin V/PI double-positivity, after cytokine deprivation. Over a series of four experiments, NO reduced significantly the percentage of Annexin V/PI double-positive T cells after cytokine deprivation (21.5 ± 3.0% as compared to 16.1 ± 1.1% in untreated and NOC-18-treated cells, respectively; p < 0.02). Interestingly, neither NO nor caspase inhibition reduced the percentage of Annexin V-positive, PI-negative T cells after cytokine deprivation (Figure 5B), suggesting that these cells, if generated, must rapidly progress to a double-positive phenotype. Finally, neither NO nor caspase-9 inhibition with z-LEHD.fmk affected the percentage of T cells containing depolarized mitochondria after cytokine deprivation, while z-VAD.fmk very minimally reduced mitochondrial depolarization (data not shown).

Figure 5. Cytokine deprivation-induced cell death is inhibited partially by caspase inhibition in human CD8 T cells.

A. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 for four days and cytokine deprived. Caspase activity was blocked by addition of the multi-caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk or the caspase-9 inhibitor z-LEHD.fmk. Cell death was measured by PI uptake. B. Human CD8 T cells were activated as in A., and then cytokine deprived. Caspase activity was inhibited with z-VAD.fmk or z-LEHD.fmk, and NO was added with NOC-18 (5 µM). Apoptosis was quantified by Annexin V/ PI staining after 48h. *p < 0.02 as compared to untreated control group.

The similarities in cytokine deprivation-induced cell death events that are affected by NO and pharmacological caspase inhibition suggested that NO could be inhibiting this cell death pathway through the inhibition of caspases. NO has been described to directly inhibit caspase activity through S-nitrosylation of their active site cysteine (29, 30). To determine whether NO affected caspase activity during cytokine deprivation-induced cell death, anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 activated CD8 T cells that were cytokine deprived in the absence or presence of NO were lysed and caspase-9 and caspase-3-like enzymatic activity measured. There was minimal caspase-9 and caspase-3-like activity in activated CD8 T cells cultured in the presence of IL-2. In response to cytokine deprivation, there was an increase in both caspase-9 and caspase-3-like activity (Figure 6A and B). The addition of NO to CD8 T cells reduced both caspase-9 and caspase-3-like activity after cytokine deprivation (Figure 6A and B).

Figure 6. NO inhibits caspase-9 and caspase-3 activity during cytokine deprivation through S-nitrosylation.

A. Human CD8 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28, and cultured in IL-2 or cytokine deprived in the absence or presence of NOC-18 for 48h. Cell lysates were prepared and caspase-9 activity measured with a fluorometric enzymatic activity assay. B. Cells were stimulated as in A. and caspase-3 activity measured. C. Cells were stimulated as in A. and cell lysates prepared. Caspase-9 was immunoprecipitated and the immunoprecipitate Western blotted for S-nitrosocysteine (SN-Cys) or procaspase-9 under non-reducing conditions. D. Cells were stimulated as in A. and cell lysates prepared. Caspase-3 was immunoprecipitated and the immunoprecipitate Western blotted for S-nitrosocysteine or procaspase-3.

We then investigated whether NO S-nitrosylates caspases during cytokine deprivation. Lysates from activated human CD8 T cells that were either cultured in IL-2 or cytokine deprived in the absence or presence of NOC-18 were prepared. Caspase-9 and caspase-3 were immunoprecipitated from these lysates, and the immunoprecipitated caspases immunoblotted under non-reducing conditions with an antibody that recognizes cysteine S-nitrosylation. Immunoblot of the caspase-9 and caspase-3 immunoprecipitates from cytokine deprived human CD8 T cells that had been treated with NOC-18 detected bands at 47 and 32 kDa respectively, which are the molecular weights of procaspase-9 and procaspase-3. Similar bands were minimally detected in cytokine deprived T cells that were not exposed to NO (Figure 6C and D). These results indicate that NO can S-nitrosylate caspase-9 and caspase-3 during cytokine deprivation.

Discussion

In the current study we show that iNOS increases the accumulation of allogeneically activated human T cells by inhibiting cytokine deprivation-induced cell death, likely through the inhibition of caspases by S-nitrosylation. Taken together with our previous finding that inhibition of iNOS in a humanized mouse model of allograft artery rejection inhibits graft rejection by reducing the accumulation of activated T cells (13), our new data suggest that NO is an important potentiator of allogeneic responses through its effects on T cell survival. To our knowledge, this is a previously unrecognized mechanism by which NO regulates allogeneic T cell responses. Our work also provides novel information on the regulation of cell death of human T cells.

Cytokine deprivation-induced cell death is a main pathway by which activated T cells are eliminated during the contraction of immune responses following pathogen infection (31, 32). In transplantation, Wells et al. (18) showed that inhibition of cytokine deprivation-induced cell death by over-expression of Bcl-xL in T cells prevented co-stimulatory blockade-induced tolerance of heart allografts, and also increased the severity of transplant vasculopathy (TV). Also, reduced Bcl-2 expression in leukocytes, which increases the sensitivity of cells to cytokine deprivation-induced cell death but not AICD, is correlated with increased leukocyte apoptosis in clinical samples of TV (33). These in vivo experiments and clinical observations underscore that cytokine deprivation-induced cell death is a relevant biological process in transplantation and understanding its mechanisms is pertinent to transplant immunology in general, and tolerance induction specifically. We have also recently described the localization of iNOS in a subset of CD8 T cells in clinical specimens of TV (12), supporting the relevance of NO production through this mechanism in clinical settings. Given the establishment of an important role of cytokine deprivation-induced cell death in organ transplant rejection (18), the 2.2 fold increase in allogeneically-activated T cell death we observe in vitro after iNOS inhibition over several days may appreciably regulate the immune response to allografts that takes place over a number of years. Indeed, an approximate two-fold increase in cell death of PD-1 positive versus PD-1 negative CD8 T cells has been suggested to account for blunted T cell responses in HIV infection (34). Also, cytokine deprivation may be particularly important in clinical settings due to the use of cyclosporine, which prevents optimal production of IL-2 (35). Further, examination of TCR sequences in clinical specimens with TV has indicated that 0--80% of the TCR sequences within allograft arteries are oligoclonal, suggesting the presence of a substantial bystander population (36, 37).

In mice, iNOS-derived NO from macrophages, mesenchymal stem cells, and dendritic cells inhibits allogeneic T cell responses (38). iNOS can also both induce and inhibit cell death in vivo, depending on the mouse model of disease examined (30, 39). Also, mice that overexpress dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase, which increases iNOS activity by degrading the endogenous iNOS inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine, have reduced TV (40). However, the biological role of iNOS is cell type specific (41), iNOS expression in humans is regulated very differently than in mouse/rat cells, and iNOS may have distinct biological functions in humans (8). Our current work is based on observations in our humanized mouse model of allograft artery rejection that iNOS blockade reduces rejection (42). The potentiation of T cell responses, and specifically proliferation, by low levels of NO has been documented by others (2, 43, 44). Our results indicate that endogenous production of NO from iNOS in human T cells does not affect proliferation of primary human CD8 T cells stimulated by allogeneic EC, although a role for NO from other sources in regulating T cell proliferation during other types of immune stimulation remains possible. However, we do show that inhibition of cell death is a main mechanism by which iNOS-derived NO increases allogeneic human T cell responses. Although other reports have suggested that exogeneous NO does not inhibit cell death during T cell activation (2), these studies examined T cell death during continuous TCR stimulation for 4--5 days, which is more likely to be AICD than cytokine deprivation-induced.

A unexplained finding of our work is that NO inhibits cytokine deprivation-induced cell death but not AICD. A possible explanation is that protein S-nitrosylation within cells is specifically regulated by the balance of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation reactions, processes which depend, in part, on specific enzymes to catalyze the addition and removal of nitrosyl groups on specific cysteines within proteins (4, 45--47). We have observed that the addition of exogenous NO does not inhibit caspase-3 activity in human T cells undergoing during AICD, consistent with the possibility that the intracellular environment of T cells undergoing AICD differs from those undergoing cytokine deprivation-induced cell death and may not support S-nitrosylation of caspases.

We have observed that neither NO nor caspase inhibitors is able to completely inhibit cytokine deprivation-induced T cell death. This may be a result of the existence of caspase-independent death pathways (13, 48). Nevertheless, multi-caspase inhibition is able to partially inhibit cytokine deprivation-induced death (13), suggesting the existence of a feedback mechanism controlled by caspases. Our observations that both NO and caspase inhibition reduced cytokine deprivation-induced cell death, as determined by PI uptake, is consistent with this notion. It is not known why neither NO nor caspase inhibition affected the percentage of Annexin V-positive, PI-negative cells. However, this phenotype is likely to be transient and cell viability may be able to be preserved in cells that contain externalized phosphatidylserine in the absence of membrane permeabilization (49). Also, viable CD8 T cells have recently been observed to externalize phosphatidylserine after TCR-mediated activation, but this is not related to cell death (50). Therefore, while the acquisition of PI-positivity clearly identifies T cells that are committed to cell death, Annexin V-single positive cells might not be an accurate indicator of CD8 T cell death. It is perhaps more puzzling that neither NO nor caspase inhibitors seem to reduce mitochondrial potential changes yet preserve viability. However, this may also be a reversible change (51).

In conclusion, we have described a previously unrecognized pathway by which NO augments human T cell responses, namely the inhibition of cytokine deprivation-induced cell death. This survival effect of NO is mediated by the inhibition of caspases by protein S-nitrosylation, which is increasingly recognized as a physiologically relevant post-translational modification controlling cellular responses and signaling (52). Our findings have implications for understanding the mechanisms regulating T cell responses in transplanted organs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL070295 (JSP), a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (JCC), and a research fellowship from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (JCC).

References

- 1.Van Der Veen RC, Dietlin TA, Pen L, Gray JD. Nitric oxide inhibits the proliferation of T-helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes without reduction in cytokine secretion. Cell Immunol. 1999;193:194–201. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niedbala W, Wei XQ, Campbell C, Thomson D, Komai-Koma M, Liew FY. Nitric oxide preferentially induces type 1 T cell differentiation by selectively up-regulating IL-12 receptor beta 2 expression via cGMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16186–16191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252464599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignarro LJ, Cirino G, Casini A, Napoli C. Nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the vascular system: An overview. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:879–886. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: Purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worrall NK, Chang K, Suau GM, et al. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase prevents myocardial and systemic vascular barrier dysfunction during early cardiac allograft rejection. Circ Res. 1996;78:769–779. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shears LL, Kawaharada N, Tzeng E, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase suppresses the development of allograft arteriosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2035–2042. doi: 10.1172/JCI119736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koglin J, Glysing-Jensen T, Mudgett JS, Russell ME. Exacerbated transplant arteriosclerosis in inducible nitric oxide-deficient mice. Circulation. 1998;97:2059–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneemann M, Schoedon G. Species differences in macrophage NO production are important. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:102. doi: 10.1038/ni0202-102a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor BS, de Vera ME, Ganster RW, et al. Multiple NF-kappaB enhancer elements regulate cytokine induction of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15148–15156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan GC, Fish JE, Mawji IA, Leung DD, Rachlis AC, Marsden PA. Epigenetic basis for the transcriptional hyporesponsiveness of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in vascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:3846–3861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szabolcs MJ, Ravalli S, Minanov O, Sciacca RR, Michler RE, Cannon PJ. Apoptosis and increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in human allograft rejection. Transplantation. 1998;65:804–812. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199803270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choy JC, Yi T, Rao DA, et al. CXCL12 induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase in human CD8 T cells. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1333–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choy JC, Wang Y, Tellides G, Pober JS. Induction of inducible NO synthase in bystander human T cells increases allogeneic responses in the vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1313–1318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607731104. Epub 2007 Jan 1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hildeman DA, Zhu Y, Mitchell TC, Kappler J, Marrack P. Molecular mechanisms of activated T cell death in vivo. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:354–359. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strasser A, Pellegrini M. T-lymphocyte death during shutdown of an immune response. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alderson MR, Tough TW, Davis-Smith T, et al. Fas ligand mediates activation-induced cell death in human T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;181:71–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng L, Fisher G, Miller RE, Peschon J, Lynch DH, Lenardo MJ. Induction of apoptosis in mature T cells by tumour necrosis factor. Nature. 1995;377:348–351. doi: 10.1038/377348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells AD, Li XC, Li Y, et al. Requirement for T-cell apoptosis in the induction of peripheral transplantation tolerance. Nat Med. 1999;5:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epperson DE, Pober JS. Antigen-presenting function of human endothelial cells. Direct activation of resting CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:5402–5412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dengler TJ, Pober JS. Human vascular endothelial cells stimulate memory but not naive CD8+ T cells to differentiate into CTL retaining an early activation phenotype. J Immunol. 2000;164:5146–5155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter AL, Choy JC, Granville DJ. Detection of apoptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Methods Mol Med. 2005;112:277–289. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-879-x:277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Alessio A, Al-Lamki RS, Bradley JR, Pober JS. Caveolae participate in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and internalization in a human endothelial cell line. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes CC, Pober JS. Transcriptional regulation of the interleukin-2 gene in normal human peripheral blood T cells. Convergence of costimulatory signals and differences from transformed T cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5369–5377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wojciechowski S, Tripathi P, Bourdeau T, et al. Bim/Bcl-2 balance is critical for maintaining naive and memory T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1665–1675. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070618. Epub 2007 Jun 1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hildeman DA, Zhu Y, Mitchell TC, et al. Activated T cell death in vivo mediated by proapoptotic bcl-2 family member bim. Immunity. 2002;16:759–767. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Parijs L, Ibraghimov A, Abbas AK. The roles of costimulation and Fas in T cell apoptosis and peripheral tolerance. Immunity. 1996;4:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer SF, Belz GT, Strasser A. BH3-only protein Puma contributes to death of antigen-specific T cells during shutdown of an immune response to acute viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3035–3040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706913105. Epub 2008 Feb 3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsden VS, O’Connor L, O’Reilly LA, et al. Apoptosis initiated by Bcl-2-regulated caspase activation independently of the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome. Nature. 2002;419:634–637. doi: 10.1038/nature01101. Epub 2002 Sep 2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melino G, Bernassola F, Knight RA, Corasaniti MT, Nistico G, Finazzi-Agro A. S-nitrosylation regulates apoptosis. Nature. 1997;388:432–433. doi: 10.1038/41237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bersimbaev RI, Yugai YE, Hanson PJ, Tzoy IG. Effect of nitric oxide on apoptotic activity in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;423:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes PD, Belz GT, Fortner KA, Budd RC, Strasser A, Bouillet P. Apoptosis regulators Fas and Bim cooperate in shutdown of chronic immune responses and prevention of autoimmunity. Immunity. 2008;28:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weant AE, Michalek RD, Khan IU, Holbrook BC, Willingham MC, Grayson JM. Apoptosis regulators Bim and Fas function concurrently to control autoimmunity and CD8 T cell contraction. Immunity. 2008;28:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu B, Sakkas LI, Slachta CA, et al. Apoptosis in chronic rejection of human cardiac allografts. Transplantation. 2001;71:1137–1146. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrovas C, Casazza JP, Brenchley JM, et al. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2281–2292. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061496. Epub 2006 Sep 2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu JO. Calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, kinases, and transcriptional corepressors involved in T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:184–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slachta CA, Jeevanandam V, Goldman B, Lin WL, Platsoucas CD. Coronary arteries from human cardiac allografts with chronic rejection contain oligoclonal T cells: Persistence of identical clonally expanded TCR transcripts from the early post-transplantation period (endomyocardial biopsies) to chronic rejection (coronary arteries) J Immunol. 2000;165:3469–3483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu B, Sakkas LI, Goldman BI, et al. Identical alpha-chain T-cell receptor transcripts are present on T cells infiltrating coronary arteries of human cardiac allografts with chronic rejection. Cell Immunol. 2003;225:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko SH, Ryu GR, Kim S, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide plays an important role in acute and severe hypoxic injury to pancreatic beta cells. Transplantation. 2008;85:323–330. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816168f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka M, Sydow K, Gunawan F, et al. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase overexpression suppresses graft coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;112:1549–1556. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537670. Epub 2005 Sep 1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poon BY, Raharjo E, Patel KD, Tavener S, Kubes P. Complexity of inducible nitric oxide synthase: Cellular source determines benefit versus toxicity. Circulation. 2003;108:1107–1112. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086321.04702.AC. Epub 2003 Aug 1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koh KP, Wang Y, Yi T, et al. T cell-mediated vascular dysfunction of human allografts results from IFN-gamma dysregulation of NO synthase. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:846–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI21767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagy G, Barcza M, Gonchoroff N, Phillips PE, Perl A. Nitric oxide-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis generates Ca2+ signaling profile of lupus T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3676–3683. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagy G, Clark JM, Buzas E, et al. Nitric oxide production of T lymphocytes is increased in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Lett. 2008;118:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.02.009. Epub 2008 Mar 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benhar M, Forrester MT, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Regulated protein denitrosylation by cytosolic and mitochondrial thioredoxins. Science. 2008;320:1050–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.1158265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Tischler V, Berk BC, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Redox regulatory and anti-apoptotic functions of thioredoxin depend on S-nitrosylation at cysteine 69. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:743–749. doi: 10.1038/ncb851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell DA, Marletta MA. Thioredoxin catalyzes the S-nitrosation of the caspase-3 active site cysteine. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:154–158. doi: 10.1038/nchembio720. Epub 2005 Jul 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammill AK, Uhr JW, Scheuermann RH. Annexin V staining due to loss of membrane asymmetry can be reversible and precede commitment to apoptotic death. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:16–21. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fischer K, Voelkl S, Berger J, Andreesen R, Pomorski T, Mackensen A. Antigen recognition induces phosphatidylserine exposure on the cell surface of human CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2006;108:4094–4101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-011742. Epub 2006 Aug 4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown NM, Martin SM, Maurice N, Kuwana T, Knudson CM. Caspase inhibition blocks cell death and results in cell cycle arrest in cytokine-deprived hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2144–2155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607961200. Epub 2006 Nov 2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: A physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]